Abstract

Objectives. To examine the prevalence and magnitude of price promotions in a major Australian supermarket and how they differ between core (healthy) and discretionary (less healthy) food categories.

Methods. Weekly online price data (regular retail price, discount price, and promotion type) on 1579 foods were collected for 1 year (April 2017 to April 2018) from the largest Australian supermarket chain. Products audited were classified according to Australian Dietary Guidelines definitions of core and discretionary foods and according to their Health Star Rating (a government-endorsed nutrient profiling scheme).

Results. On average, 15.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 14.7%, 15.3%) of core foods and 28.8% (95% CI = 28.6%, 29.0%) of discretionary foods were price promoted during a given week. Average discounts were −15.4% (95% CI = −16.4, −14.4) for core products and −25.9% (95% CI = −26.8, −25.1) for discretionary products. The percentage of products on price promotion and the size of the discount were larger for products with a lower Health Star Rating (P < .05).

Conclusions. Price promotions were more prevalent and greater in magnitude for discretionary foods than for core foods. Policies to reduce the prevalence and magnitude of price promotions on discretionary foods could improve the healthiness of food purchased from supermarkets.

Diets rich in energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods are a major contributor to poor health globally, with poor dietary intake associated with a number of diseases and chronic conditions including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and several cancers (among others).1 Despite long-standing awareness of the importance of good nutrition and its role in the obesity epidemic, poor diets and obesity remain highly prevalent worldwide.2 A likely key driver of unhealthy diets is the obesogenic nature of current food environments.

Although the proportion of food purchased in supermarkets varies according to context and level of development, supermarkets are the setting for more than 50% of all food purchased globally.3 Accordingly, supermarket environments have the potential to affect diets at a population scale.4,5 The influence of food retailers such as supermarkets can be either positive (encouraging a balanced diet consisting predominantly of nutritious, core foods that should constitute the majority of the diet) or negative (encouraging the purchase of energy-dense, nutrient-poor discretionary foods that should constitute a small part of the diet) for population health.6

Previous research has shown that most supermarkets disproportionately promote energy-dense, nutrient-poor discretionary foods in their catalogs or circulars, at checkouts, and on end-of-aisle displays and that product choice and shelf space favor less healthy foods.7–11 Such marketing techniques are designed to drive increased purchasing by customers.

Price promotions, or temporary price discounts, have also been identified as contributing to increases in the quantity of food purchased and consumed by promoting purchasing habits such as stockpiling (buying to use later).12 In a narrative review of sales promotions and food consumption, Hawkes concluded that price promotions generate substantial short-term increases in sales of the promoted product and, when applied systematically, can affect consumer purchasing patterns and ultimately consumption.13 A recent Australian industry report indicated that 40% of products are sold on price promotion in Australian supermarkets, with this figure increasing by 10% in the past 8 years. The report described Australia as “one of the most highly [price] promoted countries in the world.”14 Price promotions are a global public health issue, with more than 20% of products sold on price promotion in other developed countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Italy.14

Despite the potential impact of price promotions on population diets, few studies have examined the extent of price promotions and how promotions are applied to different food categories. A recent systematic review revealed little research describing the extent or magnitude of price promotions globally.15 Of the 4 reviewed studies that explicitly examined the availability and magnitude of price promotions, 3 showed that price promotions favored unhealthy foods and beverages. However, these prior studies were limited by their short-term nature, and they did not examine fluctuations in the prevalence of price promotions over time.16–19 In this study, we examined the frequency and magnitude of price promotions applied to products from core (healthy) and discretionary (less healthy) food categories in the largest Australian supermarket chain over a 1-year period.

METHODS

Between April 2017 and April 2018, we collected weekly online price data (regular retail price, discount price, and promotion type) from the largest Australian supermarket chain. Given the large number of food products available from the retailer’s Web site, a limited number of retailer-defined categories (n = 11) were selected for monitoring on the basis of whether they contained foods that could clearly be classified as “core” or “discretionary” (as defined by the Australian Dietary Guidelines) and that contribute significantly to population diets.20–22

Data were collected by a single researcher (Anna Paix) during the weekly price promotion cycle, with the following data entered into a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) spreadsheet: product name, product size (milliliters/grams), pack size, product category, regular retail price, special price, and type of promotion. When the promotion was a multibuy, the number of items required to be purchased for the consumer to receive the discounted price was also recorded. We developed these data collection methods for our project, as we were not aware of any existing protocols for this type of work.

To determine the validity of online data collection in comparison with prices in stores, we compared online and in-store prices and price promotions for the retailer that was the focus of this study. For the 107 core and discretionary products included in the “market baskets” of the Australian Standardized Affordability and Pricing methods protocol, we found 99% agreement between prices and price promotions displayed in stores and online.23,24

Definition of Price Promotions

A price promotion was defined as a temporary price reduction for an item. This included multibuy offers, whereby more than one unit was required to be purchased to receive the discounted price. “Everyday low prices” or other permanent price reductions as listed on the retailer’s Web site were not considered to be price promotions.

Classification of Product Healthiness

Core and discretionary.

Individual products were classified as core or discretionary foods according to the Australian Dietary Guidelines and the related Australian Bureau of Statistics criteria for discretionary foods.20,21 Breakfast cereals were the only category to include both core and discretionary products. Discretionary breakfast cereals were classified as cereals that are covered in chocolate or contain more than 30 grams of sugar per 100 grams or cereals that contain added fruit and have more than 35 grams of sugar per 100 grams.21

All food items (n = 1579) within several retailer-defined categories were included. Core foods (n = 582) consisted of low-sugar breakfast cereals (n = 117); packaged bread (n = 123); muesli and oats (n = 127); canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes (n = 94); frozen fruit (n = 37); and frozen vegetables (n = 84). Discretionary foods (n = 993) consisted of high-sugar breakfast cereals (n = 17), chips (single and multipack, including corn and potato chips; n = 214), chocolate (bars, blocks, and share packs; n = 245), ice cream (tubs and single-serve multipacks; n = 352), and confectionery (sweets, lollipops, and licorice; n = 165). Breakfast cereal variety packs that included both high-sugar (discretionary) and low-sugar (core) options were categorized separately (n = 4). No beverage categories were selected for inclusion as they were the subject of a separate similar study.25

Products not considered to fit clearly into the predefined supermarket categories were excluded from our analyses. For example, breakfast drinks and biscuits and breakfast variety packs that included high- and low-sugar cereal options as well as wheat germ and other cereal add-ons were excluded from the breakfast cereal category, and all products that were not 100% fruit or vegetable were excluded from the frozen fruit and frozen vegetable categories. All products that were not 100% beans or legumes (apart from the preserving liquid) were excluded from the canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes category.

Health Star Rating.

The Health Star Rating (HSR) was introduced by the Australian government in 2014 as a voluntary front-of-pack nutrition-labeling scheme. The HSR involves a star rating from 0.5 (least healthy) to 5.0 stars (most healthy), with 0.5 increments. The algorithm used to calculate the HSR determines overall product healthiness by assessing key components of the product, including but not limited to total energy, total sugars, saturated fat, and sodium per 100 grams.26 The HSR values for the products in our study were obtained from the regularly updated FoodSwitch Web site and mobile phone application produced by the George Institute for Global Health.27,28

When the HSR of a product was not available in the FoodSwitch database, the Web site of either the supermarket or the food manufacturer was searched to obtain the HSR. When no HSR was available from any of these sources, we calculated the HSR by entering data from the product nutrition information panel (when available online) into the online calculator on the HSR System Web site.29 When the nutrition information panel was not available or the product was a variety pack, no HSR rating was given.

Data Analysis.

The total proportion of products on price promotion each week (including price discount and multibuy promotions) and the mean magnitude of the discount were calculated for (1) each food category defined by the retailer Web site (e.g., frozen fruit; n = 11), (2) core foods and discretionary foods, and (3) 6 categories created on the basis of the HSR (0.5, 1–1.5, 2–2.5, 3–3.5, 4–4.5, and 5).

We assessed (using Microsoft Excel) differences between categories (core vs discretionary) in the mean proportion of products on price promotion and the mean depth of discount using independent-samples 2-tailed t tests assuming equal variance, with P < .05 considered statistically significant; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around means were also calculated in Excel. Seasonal variations in price promotions were examined by calculating mean weekly discounts and proportions of products on price promotion in each of the 4 Australian seasons (summer [December to February], autumn [March to May], winter [June to August], spring [September to November]). We used analyses of variance with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons to assess seasonal differences.

RESULTS

Of the 1579 products monitored over the 12-month study period, 38 (2.4%) were excluded prior to our analysis because they were not considered to fit clearly into the predefined supermarket categories or were breakfast cereal variety packs that included both core and discretionary products. We used data for 1541 (97.6%) products in our analysis (Table 1); HSRs were available for 91.9% of these products. HSRs were not available for 26 variety packs that included multiple product types and a further 98 products that had no easily accessible nutrition information. These products were excluded from all analyses involving HSRs.

TABLE 1—

Mean Percentages of Items in an Australian Supermarket on Price Promotion and Magnitudes of Discount, by Food Category: April 2017–April 2018

| Product Type | No. | Items Price Promoted, Mean % (95% CI) | Magnitude of Discount Relative to Usual Price, % Change (95% CI) | Products on Multibuy Special, Mean % (95% CI) |

| Core | 553 | 15.1 (14.8, 15.3) | −15.4 (−16.4, −14.4) | 1.9 (1.8, 2.0) |

| Low-sugar breakfast cereals | 116 | 15.0 (14.2, 15.8) | −20.0 (−22.5, −17.4) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) |

| Packaged bread | 123 | 7.5 (6.8, 8.1) | −8.4 (−10.4, −6.4) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) |

| Muesli and oats | 126 | 14.7 (13.4, 16.1) | −22.7 (−25.0, −20.5) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.3) |

| Canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes | 89 | 21.2 (19.8, 22.7) | −18.7 (−22.2, −15.3) | 7.7 (6.3, 9.0) |

| Frozen fruit | 28 | 20.4 (16.9, 23.9) | −11.6 (−15.0, −8.1) | 3.8 (1.7, 5.9) |

| Frozen vegetables | 71 | 19.2 (18.0, 20.4) | −11.0 (−13.0, −9.0) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.1) |

| Discretionary | 988 | 28.8 (28.6, 29.0) | −25.9 (−26.8, −25.1) | 3.6 (3.5, 3.6) |

| High-sugar breakfast cereals | 17 | 24.0 (18.7, 29.3) | −27.9 (−33.8, −21.9) | 0.3 (0.0, 1.0) |

| Chocolate (bar, block, share pack) | 246 | 40.3 (39.3, 41.2) | −31.3 (−33.1, −29.6) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.2) |

| Chips (multipack, singles, share pack) | 211 | 32.5 (31.8, 33.2) | −24.2 (−26.0, −22.5) | 12.0 (11.6, 12.4) |

| Ice cream | 351 | 22.1 (21.6, 22.6) | −26.9 (−28.3, −25.4) | 2.6 (2.3, 3.0) |

| Confectionery (sweets, lollipops, licorice) | 163 | 21.6 (20.7, 22.5) | −19.4 (−21.3, −17.5) | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Proportion of Products With Price Promotions

On average, 23.9% of all products available in the selected categories were price promoted during any given week (20.9% temporary price discounts, 3.0% multibuy promotions). Discretionary foods (28.8%; 95% CI = 28.6%, 29.0%) were price promoted almost twice as often as core foods (15.1%; 95% CI = 14.8%, 15.3%; P < .001).

The categories with the highest percentages of products price promoted during a given week all consisted of discretionary foods (chocolate, 40.3%; chips, 32.5%; high-sugar breakfast cereal, 24.0%; ice cream, 22.1%). The categories with the lowest percentages of products price promoted were all core foods (packaged bread, 7.5%; muesli and oats, 14.7%; low-sugar breakfast cereals, 15.0%; frozen vegetables, 19.2%).

Magnitudes of Discounts

The mean weekly magnitude of discount over the year was lower for core foods (−15.4%; 95% CI = −16.4%, −14.4%) than for discretionary foods (−25.9%; 95% CI = −26.8%, −25.1%; P < .001). The largest mean weekly price discounts were for discretionary foods (chocolate, −31.3%; high-sugar breakfast cereals, −27.9%; ice cream, −26.9%; chips, −24.2%), whereas the categories with the smallest discounts all consisted of core foods (packaged bread, −8.4%; frozen vegetables, −11.0%; frozen fruit, −11.6%; canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes, −18.7%).

Seasonal Variations

Seasonal variations in price promotions were observed for a limited number of food categories including frozen fruit; canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes; chips; ice cream; and confectionery. Ice cream was more frequently price promoted in the summer (25.5%) than in the winter (19.3%) or spring (21.0%; P < .01). Also, frozen fruit was more frequently price promoted in summer (26.6%) than winter (13.2%; P < .01). The confectionery category was more frequently promoted in the winter than in the summer (26.2% vs 19.8%; P < .01). No significant temporal differences in the price discounting of any other food categories were observed.

Multibuys

In the core foods category, 1.9% (95% CI = 1.8%, 2.0%) of products were available as a multibuy promotion each week on average, as compared with 3.6% (95% CI = 3.5%, 3.6%) of discretionary foods (P < .001). On average, 12.4% of all chips were offered as a multibuy promotion during any given week. The other 3 categories with relatively high numbers of multibuys available were canned beans, legumes, and tomatoes (7.7%); frozen fruit (3.8%); and ice cream (2.6%). Low-sugar and high-sugar breakfast cereals (0.1% and 0.3%, respectively), frozen vegetables (0.8%), muesli and oats (1.1%), packaged breads (0.4%), chocolate (0.2%), and confectionery items (0.1%) were rarely available as multibuys.

Health Star Ratings

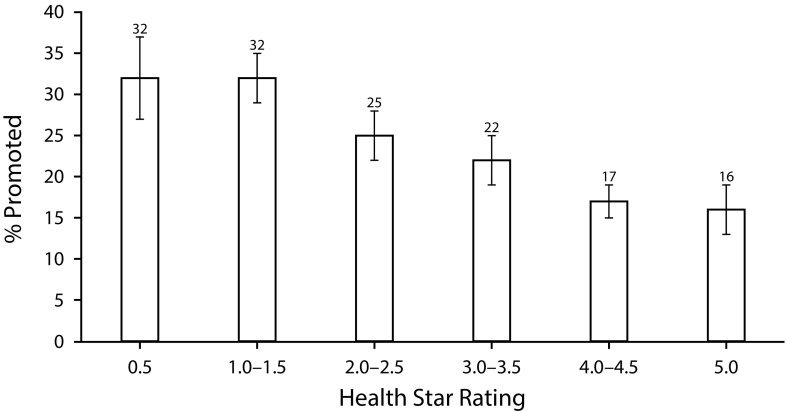

Over the 1-year study period, products with an HSR of 0.5 were more frequently price promoted (32.4%; 95% CI = 2.79%, 36.9%) than products with an HSR of 5.0 (15.9%; 95% CI = 12.9%, 19.0%; P < .001). A strong correlation was observed between HSR and the proportion of products price promoted (r2 = 0.94, P < .001), whereby the proportion of price promoted items within each HSR category decreased as HSR increased (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

Mean Percentages of Products in an Australian Supermarket on Price Promotion, According to Health Star Rating Category: April 2017–April 2018

Note. In the Australian Health Star Rating scheme, products are rated from 0.5 stars (least healthy) to 5 stars (most healthy). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Significant differences (P < .05) were observed between categories with the exception of 0.5 vs 1–1.5, 2–2.5 vs 3–3.5, and 4–4.5 vs 5.

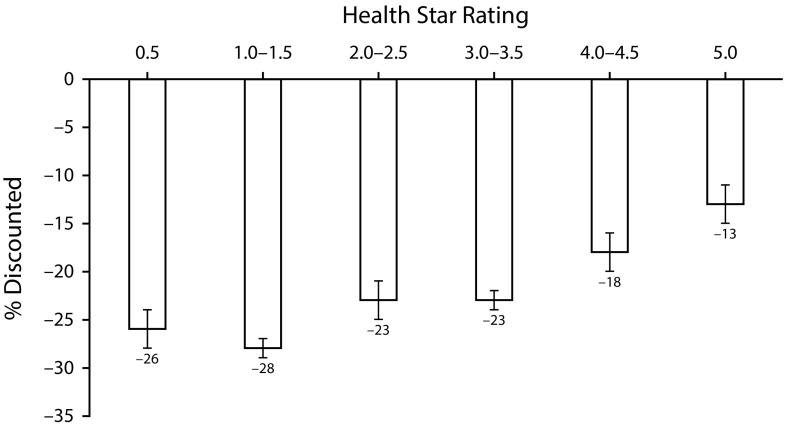

The largest average price discounts were observed for items with HSRs of 1 to 1.5 (−27.6%; 95% CI = −29.0, −26.2) and 0.5 (−26.2%; 95% CI = −28.5, −24.0). The smallest average price discount was observed for items with an HSR of 5 (−12.9%; 95% CI = −14.9, −10.9). A strong correlation was observed between HSR and magnitude of discount applied (r2 = 0.83, P < .05), whereby depth of discount decreased as HSR increased (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2—

Mean Depths of Discount in an Australian Supermarket, According to Health Star Rating Category: April 2017–April 2018

Note. In the Australian Health Star Rating scheme, products are rated from 0.5 stars (least healthy) to 5 stars (most healthy). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Significant differences (P < .05) were observed between categories with the exception of 0.5 vs 1–1.5, 0.5 vs 3–3.5, and 2–2.5 vs 3–3.5.

DISCUSSION

In this study quantifying the prevalence and magnitude of price promotions in the largest Australian supermarket chain, we found that 23.9% of all sampled products were price promoted in any given week. Discretionary foods were price promoted almost twice as often as core foods (28.8% vs 15.1%), with the magnitude of discounts also far greater for discretionary foods (−15.4% vs −25.4%). Similar patterns were observed when foods were classified according to HSR, with a strong inverse relationship between HSR and both the frequency and magnitude of price promotions. Multibuy promotions were uncommon (3.0% of all promotions).

Our results are broadly consistent with previous literature on the topic. For example, our finding that, on average, 23.9% of all food products were price promoted is comparable to the 30% of all beverages found to be price promoted in a previous study involving similar methods conducted in 2 of the largest Australian supermarkets between 2016 and 2017.25

In that study, in the largest Australian supermarket, the percentages of price promotions were higher for sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs; 37%) and artificially sweetened beverages (ASBs; 38%) than for flavored milk and greater than 99% juice (28%) and milk and water (15%); the discounts applied to the healthiest beverages were also lower (−34% for SSBs, −30% for ASBs, −20% for flavored milk and greater than 99% juice, and −23% for milk and water). These findings mirror our own results. Of interest, no obvious difference in the percentage of price promotions or magnitude of discounts was observed between SSBs and ASBs in that study. The percentage of beverage multibuys (8%) was somewhat higher than the percentage of food multibuys in our study (3.0%).

Our conclusions are also consistent with the results of a comparable study conducted in the United States over a 2-year period.18 In that study, Powell et al. collected in-store data from supermarkets, convenience stores, and limited service stores in 46 US states between 2010 and 2012. Price promotion data were collected for 44 products in the following categories: fruits and vegetables, meats and eggs, cereals and bread, and snacks and sweets. Consistent with our results, Powell et al. found that higher-sugar breakfast cereals (12.9%) were more often price promoted than lower-sugar cereals (8.7%; P ≤ .05). Moreover, they found that the discount applied was larger for higher-sugar (−23.7%) than lower-sugar (−13.4%) cereals. The prevalence of price promotions in the sampled US supermarkets (13.4%) was considerably lower than that observed in both our study (23.9%) and the Australian beverage study (30%), with these differences likely reflecting the extent to which price promotions are used in the 2 countries.30

In addition to literature examining the prevalence of price promotions, some researchers have used panel supermarket purchasing data to investigate the extent to which customers purchase products on price promotion.31,32 One US study involving electronic supermarket purchase data revealed that low-calorie foods (fruit, vegetables, low-fat dairy) were purchased with a price promotion less often (approximately 19%) than high-calorie foods (sweet and savory snacks, SSBs, grain-based snacks; approximately 26%); the discounts applied to low-calorie foods were also smaller than those for high-calorie foods (−21.2% vs −23.5%).31

A UK study in which purchase panel data were used as a proxy for availability showed no differences in the frequency of price promotions between healthy and less healthy foods and drinks (P = .27) but did reveal a trend toward larger discounts for less healthy foods than for healthier foods (P = .058).32 Importantly, it was reported that the sales uplift arising from price promotions was larger for less healthy foods, with this effect most marked among individuals from the lowest socioeconomic group.32

Our study is the first of its kind, to our knowledge, to monitor price promotions across an entire year. Having a full year of data collection, we were able to examine not only the frequency and depth of price promotions but also seasonal variations. Little seasonal variation was observed with the exception of products that have clear seasonal differences in consumption (e.g., ice cream). Also, to our knowledge this study is the first of its kind to examine the prevalence of price promotions for core and discretionary foods in an Australian supermarket. Furthermore, our use of the Australian government–endorsed HSR system for classifying the healthiness of products with price promotions represents a novel and policy-relevant application of the HSR system. Consistent use of the HSR system for classifying the healthiness of products is likely to contribute to greater policy coherence across a range of measures for improving population diets in Australia.33

Limitations

Limitations of our study include the fact that, despite the auditing of more than 1500 products, the foods examined represent only a subset of all foods available on the supermarket Web site, and the chain selected is only one Australian supermarket retailer (albeit the largest, with a 32.2% market share). It is also important to note that the categories included in our study were specifically selected because they contained foods that were clearly core or discretionary and that contribute significantly to population diets.22

Furthermore, fresh fruit and vegetables were not included in our analysis because their price varies largely according to seasonal fluctuations. When they are in season, their price is lower, but this would not be considered a price discount as there is no standard recommended retail price for these items. Although we included a large number of food categories, the prevalence and magnitude of price promotions within other categories (analyzed according to HSRs) might reveal results different than those observed here.

Public Health Implications

We are not aware of any jurisdiction globally that has implemented regulatory measures to reduce the influence of price promotions on unhealthy foods and beverages. The UK government, however, has recently proposed policies to restrict the promotion (including price promotion) of discretionary foods that could eventually provide real-world opportunities for evaluation of consumer and industry responses to such regulation.34 Regulation of price promotion should be considered in relation to the taxes (included an SSB-specific tax) that have been implemented in a number of countries and that have been found to be effective in changing purchasing patterns.35,36 The interaction between taxes and price promotions and the ways in which the food and beverage industry responds to regulations relating to one or both of these strategies are likely to be complex and require further study. Evaluations of real-world implementations of such policies are likely to provide the best evidence of effectiveness.

Price promotions, including both temporary price reductions and multibuy offers, are clearly more prevalent among discretionary foods in the Australian supermarket studied. Also, the depth of discount was far greater for unhealthy discretionary foods than for healthier core foods. Price promotions are clearly an important, yet understudied, component of the food environment that warrant attention as part of a comprehensive strategy to address diet and obesity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Deakin University. Kathryn Backholer and Gary Sacks were supported by a Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (102047, 102035) from the National Heart Foundation of Australia. Adrian J. Cameron was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE160100141).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Gary Sacks and Adrian J. Cameron are academic partners in a healthy supermarket intervention trial that includes Australian local government and supermarket retail collaborators.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

No protocol approval was necessary for this study because no human participants were involved.

REFERENCES

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Obesity and overweight increasing worldwide. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/infographic/obesity-and-overweight-increasing-worldwide. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 3.Roger S. Omnichannel report: finding growth in reinvented retail. Available at: https://www.kantarworldpanel.com/global/News/Omnichannel-report-Finding-growth-in-reinvented-retail. Accessed November 30, 2018.

- 4.Holsten JE. Obesity and the community food environment: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(3):397–405. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The built environment and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place. 2010;16(2):175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkes C. Dietary implications of supermarket development: a global perspective. Dev Policy Rev. 2008;26(6):657–692. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron AJ, Sayers SJ, Sacks G, Thornton LE. Do the foods advertised in Australian supermarket catalogues reflect national dietary guidelines? Health Promot Int. 2015;32(1):113–121. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron AJ, Thornton LE, McNaughton SA, Crawford D. Variation in supermarket exposure to energy-dense snack foods by socio-economic position. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(7):1178–1185. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012002649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornton LE, Cameron AJ, McNaughton SA, Worsley A, Crawford DA. The availability of snack food displays that may trigger impulse purchases in Melbourne supermarkets. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlton EL, Kähkönen LA, Sacks G, Cameron AJ. Supermarkets and unhealthy food marketing: an international comparison of the content of supermarket catalogues/circulars. Prev Med. 2015;81:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crino M, Sacks G, Dunford E et al. Measuring the healthiness of the packaged food supply in Australia. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):702. doi: 10.3390/nu10060702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandon P, Wansink B. When are stockpiled products consumed faster? A convenience-salience framework of postpurchase consumption incidence and quantity. J Mark Res. 2002;39(3):321–335. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawkes C. Sales promotions and food consumption. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(6):333–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeviani R. Are we really getting value from our promotions? Available at: https://www.nielsen.com/au/en/insights/news/2018/are-we-really-getting-value-from-our-promotions.html. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 15.Bennet R, Zorbas C, Huse O . Prevalence of food and beverage price promotions and their influence on consumer purchasing behavior—a systematic review of the literature [report] Geelong, Victoria, Australia: Deakin University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravensbergen EA, Waterlander WE, Kroeze W, Steenhuis IH. Healthy or unhealthy on sale? A cross-sectional study on the proportion of healthy and unhealthy foods promoted through flyer advertising by supermarkets in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):470. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1748-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Exum BH, Thompson S, Thompson L. A pilot study of grocery store sales: do low prices = high nutritional quality? Nutr Food Sci. 2014;44(1):64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell LM, Kumanyika SK, Isgor Z, Rimkus L, Zenk SN, Chaloupka FJ. Price promotions for food and beverage products in a nationwide sample of food stores. Prev Med. 2016;86:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price R, Livingstone M, Burns A, Furey S, McMahon-Beattie U, Holywood L. What foods are Northern Ireland supermarkets promoting? A content analysis of supermarket online. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76:OCE3. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Available at: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 21.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: users’ guide, 2011–2013. Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4363.0.55.001Chapter65062011-13. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 22.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Health Survey: nutrition first results—foods and nutrients, 2011–2012. Available at: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/lookup/4364.0.55.007main+features12011-12. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 23.Lee AJ, Kane S, Lewis M et al. Healthy diets ASAP—Australian Standardised Affordability and Pricing methods protocol. Nutr J. 2018;17(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zorbas C, Lee AJ, Peeters A et al. Using online data collection methods to estimate the price and affordability of healthy and less healthy diets under different pricing scenarios. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2019;13(3):269–270. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zorbas C, Gilham B, Boelsen-Robinson T et al. The frequency and magnitude of price-promoted beverages for sale in Australian supermarkets. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2019 doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12899. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones A, Shahid M, Neal B. Uptake of Australia’s Health Star Rating System. Nutrients. 2018;10(8):997. doi: 10.3390/nu10080997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunford E, Trevena H, Goodsell C et al. FoodSwitch: a mobile phone app to enable consumers to make healthier food choices and crowdsourcing of national food composition data. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2(3):e37. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.George Institute for Global Health. FoodSwitch. Available at: https://www.foodswitch.com.au/#/home. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 29.Government of Australia. Health Star Rating Calculator. Available at: http://healthstarrating.gov.au/internet/healthstarrating/publishing.nsf/Content/online-calculator#/step/1. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 30.Frank LD, Saelens BE, Powell KE, Chapman JE. Stepping towards causation: do built environments or neighborhood and travel preferences explain physical activity, driving, and obesity? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1898–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phipps EJ, Kumanyika SK, Stites SD, Singletary SB, Cooblall C, DiSantis KI. Buying food on sale: a mixed methods study with shoppers at an urban supermarket, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010–2012. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E151. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura R, Suhrcke M, Jebb SA, Pechey R, Almiron-Roig E, Marteau TM. Price promotions on healthier compared with less healthy foods: a hierarchical regression analysis of the impact on sales and social patterning of responses to promotions in Great Britain. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(4):808–816. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.094227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Health Star Rating system on track [media release]. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia: Minister for Health; 2014.

- 34.UK Department of Health and Social Care. Childhood obesity: a plan for action. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action-chapter-2. Accessed July 28, 2019.

- 35.Smed S, Scarborough P, Rayner M, Jensen JD. The effects of the Danish saturated fat tax on food and nutrient intake and modelled health outcomes: an econometric and comparative risk assessment evaluation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(6):681–686. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batis C, Rivera JA, Popkin BM, Taillie LS. First-year evaluation of Mexico’s tax on nonessential energy-dense foods: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(7):e1002057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]