Abstract

Across the United States, physicians are prescribing patients nature. These “Nature Rx” programs promote outdoor activity as a measure to combat health epidemics stemming from sedentary lifestyles. Despite the apparent novelty of nature prescription programs, they are not new. Rather, they are a reemergence of nature-based therapeutics that characterized children’s health programs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These historic programs were popular among working-class urban families, physicians, and public health officials. By contrast, adherence is a challenge for contemporary programs, especially in socially disadvantaged areas. Although there are differences in nature prescription programs and social context, historical antecedents provide important lessons about the need to provide accessible resources and build on existing social networks. They also show that nature—and its related health benefits—does not easily yield itself to precise scientific measurements or outcomes. Recognizing these constraints may be critical to nature prescription programs’ continued success and support from the medical profession.

In July 2017, the Philadelphia Inquirer announced that “Philly doctors are now prescribing park visits to city kids.” The article detailed NaturePHL, a collaborative program in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, between the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, Philadelphia’s Parks and Recreation Department, and the US Forest Service. Readers learned that patients in two of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s primary care clinics would receive an “action plan” to spend time outside by connecting them with parks and playgrounds throughout the city.1

Philadelphia’s NaturePHL is part of a growing trend. According to the National ParkRx Initiative, there are 75 to 100 nature prescription programs across the United States that share similar structures and objectives.2 For children’s programs, pediatricians prescribe time in green space for patients, citing a growing scientific literature that indicates that children who spend more time outside increase physical activity,3 improve attention,4 and have lower rates of depression.5 NaturePHL, like many nature prescription programs, is a collaboration between pediatricians, environmental groups, government agencies, private corporations, and urban families.

Despite the apparent novelty of these programs, they are not new. Rather, they are a modern version of nature-based therapeutics that characterized children’s health programs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.6 Across time there are overlaps in nature-based programs’ goals. They have all sought to use “nature” to transform urban children’s health, ameliorate malnutrition, and improve children’s psychological and physical well-being. There is also a common medical rhetoric. Now, as then, physicians, nurses, and public health officials understand that impoverished urban children are especially vulnerable to certain health issues, even if the specific diagnoses have changed over time.7 Moreover, medical professionals lament the limited time children spend outdoors in green space, and advocate time in nature to improve physical health and mental well-being.

As we would expect, there are also key differences between the early 20th century and today. Historically, nature-based health programs enjoyed widespread popularity among families, philanthropists, and physicians. Today, however, many urban families report that going to a park is not of interest or importance to them, likely because of safety concerns.8 Health issues also differ. Historical programs served children who were underweight; those with orthopedic conditions like polio, rickets, and tuberculosis; and babies with “summer diarrhea.” In contrast, screen time, among other issues, has led to increasingly sedentary lifestyles in the 21st century, and contemporary children struggle with overweight and obesity as well as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and depression.9

Despite these divergent trends, we argue that historical antecedents offer insight into the importance of recognizing and ameliorating social, cultural, and infrastructural barriers to garnering popular support for present-day programs. Drawing from the past suggests that making parks accessible, providing needed resources, and building on existing social networks are keys to programs’ success. We also argue that historical programs provide a cautionary tale about the difficulty of evaluating the efficacy of nature-based medical programs.

Examining the trajectory of historical programs highlights potential consequences for quantifying nature’s impact. In the 19th century, miasmatic theory tied patients’ health and disease to their environments, and doctors commonly recommended that their patients change environments.10 At the turn of the 20th century, practitioners continued these practices but sought to align natural therapeutics with new scientific ideologies. They distilled and dosed nature’s therapeutic mechanisms, claiming that the sun’s UV rays, ocean water’s chemical composition, and fresh air’s ozone-free qualities improved children’s health. These investigations lead to technological solutions, such as UV lamps and saline solution that could replicate nature’s tonic elements within clinics.11 Although some institutions continued to serve urban children, by the 1930s American physicians’ participation in nature-based programing declined as they moved children from the outdoors to inside urban hospitals.12

Today, new scientific studies enumerate myriad benefits to spending time in green space. As physicians, nurses, and public health officials once again begin to support nature-based programs, they are confronting issues both old and new. They are tackling how to account for the experiential knowledge and holistic benefits of nature-based programs that are not easily quantified. What variables are necessary for nature prescriptions to “work” and be worthwhile to physicians and program sponsors? More critically, what will make these programs worthwhile for families? Historical case studies provide insight into elements that may help or hinder contemporary nature programming’s success.

HISTORY OF ENVIRONMENTAL THERAPEUTICS FOR CHILDREN

Fresh air institutions proliferated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in response to the intense industrialization in cities, poor housing conditions, and children’s resulting medical problems. The institutions provided children with “country weeks”—short stays in the country—as well as fresh air funds, playgrounds, preventoriums, open-air schools, and marine hospitals.13 These programs had a wide range of objectives, from providing a safe place to play to treating dying infants and children. Yet their commonalities are as important as their differences; all of these institutions promoted time outdoors as beneficial to children’s health and well-being.

The physicians, philanthropists, and religious leaders who opened nature-based programs believed that the urban environment caused diseases—from infantile diarrhea and “debility” to rickets and tuberculosis of the joints and spine.14 Child welfare advocates pointed to high rates of infant mortality, “crippled” children, and injurious accidents as proof of cities’ harmful effects.15 Pollution was a particularly problematic issue. In a 1926 AJPH article, Frederick Tisdall, a physician in Toronto, Canada, lamented that in American cities the sun’s rays were “readily absorbed by the smoke, dust and moisture of our atmosphere and on this account are markedly diminished.”16 He argued that “sunlight is essential to life,” that it could cure and prevent diseases like rickets, and that mothers should be taught that sunlight’s health benefits included straighter limbs and spines. He proclaimed that “the best results are obtained by telling mothers that they must get their children sunburnt.”17

Although few physicians went that far, Tisdall’s remarks are representative of public health officials’ and physicians’ belief that fresh air and sunlight held curative and preventive potential. Philadelphia serves as an instructive historical case study as it boasted a variety of philanthropic institutions that temporarily removed children from the city center. Two of these programs were the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia (SAP) and the Children’s Seashore House.

In 1877, prominent Philadelphia businessmen, lawyers, and physicians founded the philanthropic SAP. The group wanted to provide “an accessible open-air resort where hundreds of sick children, who might otherwise perish for want of such advantages, could go daily and be under the care of medical attendants.” They sought children “who through poverty are confined to unsanitary homes, unable to breath fresh country air or improve their unhealthy surroundings” and brought them to the park.18 To achieve this goal, they opened a playground on Windmill Island in the Delaware River located between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Camden, New Jersey. When that location became waterlogged after a tornado and threatened by shipping interests, the SAP’s managers moved the playground seven miles downriver to an 81-acre park in Red Bank, New Jersey.19

Ferries shuttled children and visitors between Philadelphia and the SAP. As one person reported, “It was a treat to see the poor children who enjoy their trip upon the water, and a greater one when the boat reached its landing at the Jersey shore; there were swings, bathing pools, and hammocks.”20 In addition to playing and relaxing, children enjoyed bowls of hot soup, biscuits, and milk during their stay.21 Mothers had tea at 3 pm.22 Children received clothing at no cost.

The SAP also provided child care. Although the institution welcomed mothers, they allowed children to attend on their own or with an older sibling. In its annual report for 1913, the institution published an account of a benefactor escorting three children to the playground, despite having only met them on the street corner that day and not having spoken with the mother before they departed. As the scene played out, a neighborhood woman called out to ask where they were going. Apparently unperturbed by the children’s chaperone, she ironically admonished the children, “Don’t yees get hurted or drowned . . . or your mother’ll beat you black and blue when yees git back.”23

By all measures available at that time, the institution was a success. In 1878, one of the SAP’s physicians, William Hutt, declared, “The result of our work has been a reduction in the death rate of children under five years in our city by one-half.”24 Although such proclamations are impossible to prove, we can infer that urban families believed that the SAP was a valuable resource.25 In 1878, the institution admitted 42 479 visitors, including infants, children, and mothers. In 1901, more than 125 000 visitors used the park, with an average of almost 2000 children and caretakers attending each day.26 According to the institution’s secretary, Eugene Wiley, the Sanitarium Association cared for 2 304 094 women and children during 23 years of operation.27 Urban families’ widespread use of the SAP suggests they appreciated the services and enjoyed the park. The provision of child care, free transportation, garments, food, and open green space likely contributed to the institution’s popularity among working-class families.

Urban families supported other Philadelphia-based programming as well. In 1872, a group of wealthy Philadelphians opened the Children’s Seashore House (CSH), a philanthropic hospital that provided “the benefits of sea air and bathing to such invalid children of Philadelphia, and its vicinity, as may need them, but whose parents may not be able to meet the expenses of a residence at a boarding house, and the necessary medical advice.”28 The institution was run by a staff of nurses and physicians. Philadelphia-based charities and hospitals referred families who were admitted to the CSH regardless of race, religion, nationality, or ability to pay.

Children and mothers took a train to Atlantic City, New Jersey, and generally stayed at the hospital for one to two weeks during the summer months. It was an inexpensive way to access the popular seashore resort. Railroad companies subsidized train tickets, and the hospital charged between $2 and $3 per week for food and lodging or waived the fee for destitute families.29

William Bennett, the physician in charge of the CSH, echoed other elite physicians’ claims that the seashore’s environment was uniquely capable of curing urban children with conditions ranging from asthma to eczema to tuberculosis.30 He bemoaned that most people would not be able to “see the wonderful transformation which Nature is constantly working in our invalid children,” so he relayed stories of patients’ transformations to convince donors of the hospital’s benefits (Figures 1 and 2).31

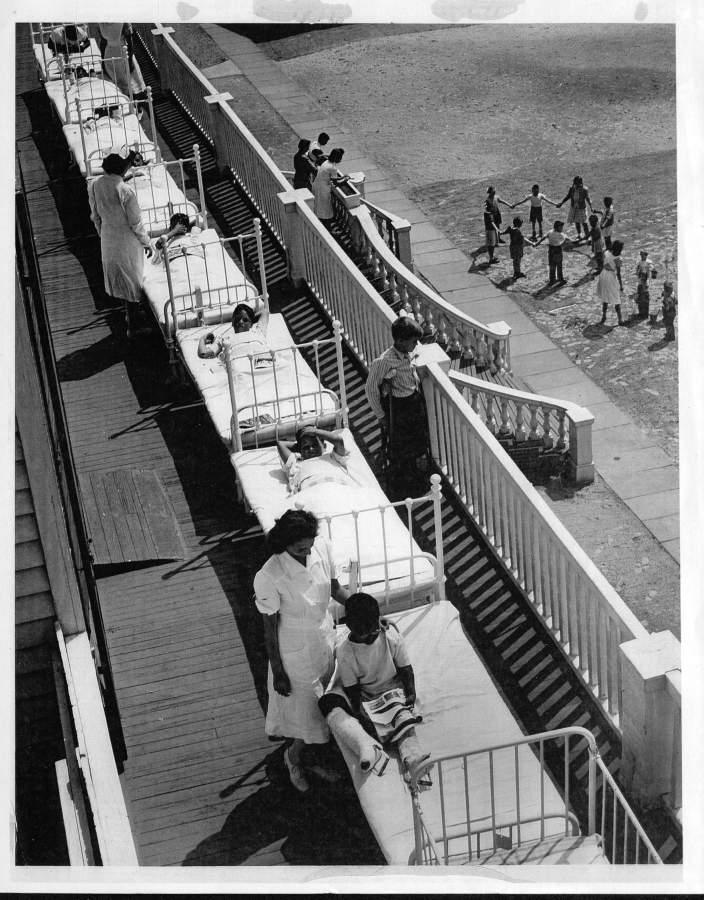

FIGURE 1—

Nurses With Patients on the Atlantic City Boardwalk

Note. The boardwalk afforded patients with access to sea air, as well as entertainment during their hospital stays.

Source. Property of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, available from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. MSS 6/0013–02-003. Printed with permission.

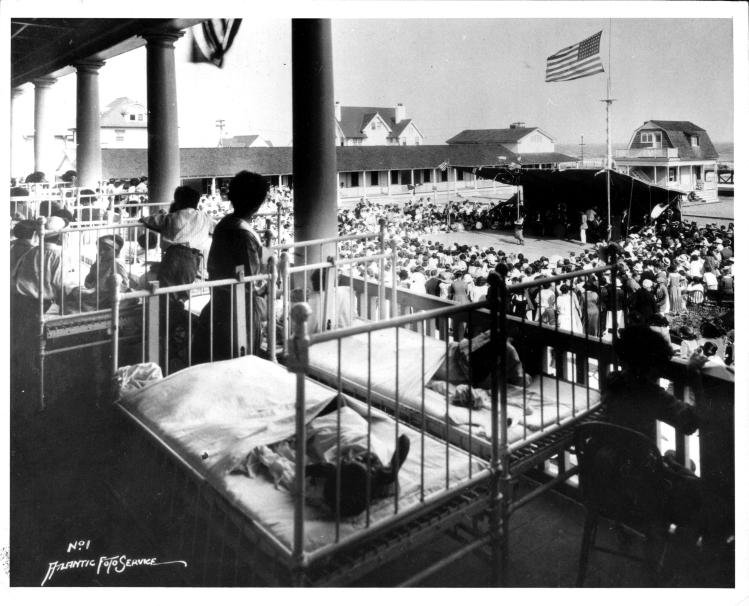

FIGURE 2—

Patients at Children’s Seashore House Enjoy Fresh Air

Source. Property of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, available from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. MSS 6/0013–02-003. Printed with permission.

Urban families did not need to be convinced. The CSH often received more requests for admission than they could accommodate. Admitted families stayed in one of the beachfront Mothers Cottages: small, private units located between the main hospital and the ocean. Children admitted without their parents stayed in one of the wards in the large, multistoried hospital building. While at CSH, children spent their days on the beach, flying kites, building sand castles, and swimming in the ocean, under the watchful eyes of nurses and mothers (Figure 3).32 Everyone ate together in the dining hall.

FIGURE 3—

View From the Porch of the Children’s Seashore House, During a Performance

Note. The Mother’s Cottages are visible in the upper left; the ocean is visible just beyond the small two-story building in the upper right.

Source. Property of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, available from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. MSS 6/0013–02-000. Printed with permission.

The CSH logbooks of patient admissions suggest that working-class mothers appreciated the communal aspects of the institution and used it as a site for health and leisure. Mothers brought healthy children to the hospital, and families and neighbors traveled and stayed together. Many families returned for multiple summers.33 Such practices likely engendered participation among urban communities.

The CSH, like the Sanitarium Association, enabled urban families to access nature through subsidized programs. Both institutions provided food, clothing, child care, and a safe place for children to play, and they allowed mothers to maintain their social and familial connections. Families demanded access, and shared the view of physicians that time in nature was time well spent.

OUT OF NATURE, INTO THE CLINIC

Despite their popularity, nature-based therapeutic programs faded from medical practice over the 20th century, even while some continued to serve children. Physicians celebrated their institutions’ success with little pushback through the first decades of the 20th century. The SAP’s medical superintendent claimed responsibility for reducing Philadelphia’s infant mortality rate, whereas physicians at the CSH reported quantifiable measures of patients’ improvement, such as weight gained and counts of patients who were discharged “well.”34 Physicians also relayed stories of patients’ newly straightened spines, rosy cheeks, healed wounds, and rounded bellies. Children’s bodies bore testament to the tonic effects of nature.

Yet corporal evidence was not enough to sustain medical investment. By the early 20th century, physicians published articles in elite journals, including the Journal of the American Medical Association and the British Medical Journal, that quantified the benefits of time at the shore, including increased metabolism,35 high opsonic indices,36 oxidation of blood,37 weight gain, and diseases arrested and cured.38 Scientists and doctors sought to calculate and quantify patients’ results, thereby aligning their practices within the dominant trend of scientific medicine.

Efforts at quantifying nature’s therapeutic impact, however, could not sustain medical investment. By the mid-20th century, doctors had largely abandoned nature-based therapeutic programs, and many institutions shuttered.39 The Sanitarium Association continued to serve Philadelphia’s youth, but it morphed into a combination of soup kitchen and playground. These changes aligned the institution with programs like the Fresh Air Fund in New York City, operating primarily as a social rather than a medical program.40 Although programs continued to promote the health benefits of spending time outside, physicians no longer served central roles in the institutions.

The CSH followed a different trajectory. It remained a hospital in Atlantic City until 1990, when it moved to Philadelphia.41 Throughout the 20th century, nurses, physicians, surgeons, and other health care providers dominated the CSH; however, their primary mode of treatment shifted from environmental to technological, as they built surgical suites and employed an orthopedic surgeon as its physician in charge.

These changes aligned with trends within medical practice over the 20th century. Historians have documented medicine’s increasingly laboratory-oriented, technologically dependent, and hospital-based professionalization, and its move away from environmental ideologies and practices.42 As historian Christopher Sellers has argued, when medical practices coalesced inside urban hospitals and around technological systems in the early 20th century, physicians ceased to consider patients’ environments when determining diagnosis, treatment, or care.43

By the 1920s, even champions of environmental therapeutics foresaw its decline. In 1926, physician R. I. Harris implored his colleagues not to abandon “heliotherapy” (natural sunlight therapy) to treat tuberculosis. Harris acknowledged that “following many cases we are convinced that it does produce a beneficial action, even though we cannot follow it in all the devious and obscure channels through which it operates.”44 Rhetorically, Harris placed heliotherapy alongside other empirically derived interventions like smallpox vaccination, digitalis, and quinine, arguing that “our ignorance of the nature of its action is no reason why we should discard it or limit its application.”45

Harris’ plea fell on deaf ears. Instead of sending children outside into the sun, physicians turned on UV lamps and recommended vitamin D–fortified foods.46 The development of vaccines and the mass production of antibiotics enabled pediatricians to prevent and cure many of the conditions that once filled nature-based institutions. Environmental medicine retreated to a few fields that focused on environmental toxins and pathogens that caused diseases.47 Over the 20th century, environmental programming continued, but doctors no longer prescribed them. Technology, physicians saw, replicated nature, and being outdoors was no longer medically necessary.

PRESCRIBING NATURE ONCE MORE

Today, physicians’ support for programs that provide urban children with access to nature is once again building, as scientific studies are finding improved health outcomes associated with time spent in green space. Within cities, physicians are prescribing time in nature for children through dozens of programs offered across the United States. Farther afield, the National Park Service and the US Forest Service have initiatives—such as Every Kid a Park, Healthy Parks Healthy People, and Discover the Forest—to increase access to national parks and forests.48

Despite renewed interest, these urban-based initiatives face numerous challenges. Now, as then, they are grappling with how to scientifically prove their intervention’s success through quantifiable measures. This task is more pronounced today than yesteryear. In the 21st century, physicians and patients understand their bodies, environments, and health within a biomedical model that has largely defined these as separate spheres with limited overlap or influence.49 Moreover, physicians demand scientific proof as evidence of a program’s benefits.

Philadelphia’s NaturePHL is an instructive example of these emerging programs, both for the health benefits they promote and the challenges they face. Established in 2014, NaturePHL’s objective is to increase the amount of time urban children play outdoors by connecting them with parks and playgrounds in the city and beyond. Similar to its predecessors, NaturePHL is led by a nonprofit organization, the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, that works in collaboration with medical and governmental agencies, parks, and public health professionals. Nature prescription programs today are often grassroots and depend on the unfunded efforts of individual care providers, parks managers, and other public employees. Funding for NaturePHL is obtained from a mix of private industry (such as health insurance companies), private philanthropic groups, and government agencies.

Primary care physicians administer NaturePHL in Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia clinics. During annual well-child visits, physicians inform patients about the benefits of time outside. They then refer families to the NaturePHL Web site to locate nearby parks. The physicians provide guidance to children with diagnoses of ADHD, anxiety, depression, or being overweight or obese, and children who indicate spending limited time outdoors. Families can work with a Nature Navigator, who facilitates their access to one of the city’s public parks or nature programs.

NaturePHL, like contemporary counterparts, builds on recent scientific evidence that quantifies the benefits of spending time outdoors.50 Studies have demonstrated that children who live in greener environments have lower blood pressure51 and enjoy increased outdoor time and physical activity.52 Children’s exposure to urban green space can also improve attention, especially for children with ADHD,53 and lessen depression.54

As in the early 20th century, urban youths struggle with malnutrition and chronic health issues. They also face challenges that are unique to the 21st century. The average American child now spends nearly eight hours a day watching a screen.55 Sedentary activities prevent children from meeting the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation of at least 60 minutes of physical activity each day; only approximately 8% of youths in the United States achieve this standard.56 The statistics are even worse for low-income urban children,57 reflected in that population’s higher rates of obesity and overweight.58

As in the late 19th century, doctors today see nature as a tool to combat ills associated with the urban environment. However, many current nature prescription programs, such as NaturePHL, rely on patients’ access to nearby urban parks and green spaces, rather than transporting patients to natural areas outside of the city. This is in part because of the increased acreage of quality parks in urban areas after numerous phases of parks development in the 20th century,59 as well as the lack of funding to bring patients out of the city and provide room, board, activities, and care.

Another issue facing nature programming is that parents today may not view the benefits as outweighing the potential drawbacks. Fear of crime and crime itself can prevent people from using parks.60 A 2014 survey of Philadelphia residents reported that residents’ concerns about safety—namely, crime and violence—in neighborhoods and nearby parks were a major barrier to spending more time outside. In Philadelphia, some of this apprehension stems from overpolicing and racial tensions in the 1960s and 1970s centered around one of Philadelphia’s major park systems.61 Current feelings of safety around Philadelphia’s parks may be influenced by these historic events.

Families’ concerns about the safety of parks and playgrounds are particularly noteworthy. Philadelphia’s park system spans 9200 acres, covering more than 10% of the urban landscape.62 Historically, families viewed playgrounds and programs like SAP as offering a safer place for children to play than the city streets, and they traveled miles to access these healthy environments. Today, urban parks and green spaces are more prevalent in urban neighborhoods, are less affected by industrial air pollution, and in many cases can provide retreat from urban stressors. Despite improved conditions and access, in a 2014 survey, 60% of city residents said they visited a park infrequently or never and 88% reported never participating in a park program because of lack of information or interest.63

Even families who want to frequent parks face barriers. Work schedules are difficult to navigate, particularly in single-parent households. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2017, 32% of children lived with one parent and 3% had no parent at home, compared with 8.5% of children who lived in single-parent homes in 1900.64 Mothers today are more likely to work outside the home, and social norms have shifted such that the older siblings and “little mothers” who once escorted children to parks, including the SAP, would now be seen as too young and vulnerable to do so.65

Yet the popularity of programs that have operated since the 19th century, including the Fresh Air Fund and the Sanitary Association (now called Soupy Island), suggests that urban families still try to provide their children with access to nature, at least beyond the city limits. The questions become how urban programs address families’ concerns about safety, facilitate access, break down barriers, and encourage families’ participation in city-based nature prescription programs.

LESSONS LEARNED

Historical institutions provide possible answers to these questions. The SAP and CSH allowed families to access parks, playgrounds, beaches, and open-air settings by providing child care, transportation, food, and clothing for free or at reduced rates, and by encouraging urban families to maintain their city-based social networks throughout their stay.

Although social, cultural, and medical contexts have changed over the past two centuries, we can glean important lessons from the successes of these historical nature-based health programs. Nature prescription programs like NaturePHL can look to ventures like the SAP and the CSH for lessons on providing infrastructure and resources that meet families’ needs, whether it is food, transportation to green spaces inside as well as outside the city, or a safe place for kids to play. The mechanisms and partnerships necessary to provide this infrastructure will need to be developed according to context. By making these experiences fun and fostering a sense of community, nature-based programs may begin to take deeper root. Although popular and medical perceptions about the environment’s role in health has changed, public and health professionals alike recognize that time outside improves urban children’s health.

Historical programs also provide a cautionary tale. Even with medical and popular support, nature prescription programs may once again fade from medical practice unless health care professionals determine how to evaluate the benefits of time spent outside. This is critical given that some physicians remain skeptical about the medical value of such programming.66 Although the scientific evidence of nature’s benefits has grown, we still need to assess nature-based programming’s impact. On a local scale, research and evaluation of NaturePHL’s impact is under way to test adherence to the program, as well as health outcomes such as stress reduction. Much as nature-based therapeutic programs did in the early 20th century, researchers will evaluate before-and-after changes among patients to analyze the potential of nature to improve urban children’s health and well-being.

Yet historical experience indicates that nature does not easily yield itself to scientific precision. Nature’s holistic actions can be difficult to isolate, and its impacts on children’s physical and mental well-being are hard to pinpoint. Ideally, parks prescription programs will be able to provide scientific proof of what many people already sense: that time in nature makes us feel better.

If scientific evidence does not support the idea that nature makes children healthier, perhaps today we can all heed Harris’ 1926 advice to embrace the experiential and corporal evidence of the benefits of time spent in nature. It is important to pursue the role of nature not only in physiological processes but also in general well-being and in our common social history. If we don’t, nature and its benefits may once again fade from medical practice and memory.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors of the Journal, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their astute feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

See also Warren, p. 1316.

Endnotes

- 1.Melamed S. “Philly Doctors Are Now Prescribing Park Visits to City Kids,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 5, 2017, http://www.philly.com/philly/health/kids-families/why-philly-doctors-are-prescribing-park-visits-to-city-kids-20170706.html (accessed June 4, 2018)

- 2. N. Seltenrich, “Just What the Doctor Ordered: Using Parks to Improve Children’s Health,” Environmental Health Perspectives 123, no. 10 (2015): A254–A259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. H. Christian, S. R. Zubrick, S. Foster, et al., “The Influence of the Neighborhood Physical Environment on Early Child Health and Development: A Review and Call for Research,” Health & Place 33 (2015): 25–36; G. Lovasi, J. Jacobson, J. Quinn, et al., “Is the Environment Near Home and School Associated With Physical Activity and Adiposity of Urban Preschool Children?” Journal of Urban Health 88, no. 6 (2011): 1143–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. I. Markevych, C. Tiesler, E. Fuertes, et al., “Access to Urban Green Spaces and Behavioural Problems in Children: Results From the GINIplus and LISAplus Studies,” Environment International 71 (2014): 29–35; E. Amoly, P. Dadvand, J. Forns, et al., “Green and Blue Spaces and Behavioral Development in Barcelona Schoolchildren: The BEATHE Project,” Environmental Health Perspectives 122, no. 12 (2014): 1351–1358. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5. J. Maas, R. Verheij, S. de Vries, et al., “Morbidity Is Related to a Green Living Environment,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63, no. 12 (2009): 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. On fresh air campaigns, see Julia Guarneri, “Changing Strategies for Child Welfare, Enduring Beliefs About Childhood: The Fresh Air Fund, 1877–1926,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 11, no. 1 (2012): 27–70; Richard A. Meckel, “Open-Air Schools and the Tuberculous Child in Early 20th-Century America.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 150, no. 1 (1996): 91–96. Several essays in M. Gutman and N. De Coninck-Smith, eds., Designing Modern Childhoods: History, Space, and the Material Culture of Children (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008) discuss programs focused on exposing children to fresh air, including open air schools, parks, and camping. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7. For instance, at the turn of the 20th century, physicians and other child welfare advocates blamed cities for causing high rates of summer diarrhea, rickets, nonpulmonary tuberculosis, and malnutrition or being underweight among children. Today, children’s urban environments are blamed for issues including asthma, obesity, lead poisoning, and anxiety. Although the diagnoses differ, the urban environment remains a common cause or risk factor.

- 8. P. Tandon, C. Zhou, J. Sallis, et al., “Home Environment Relationships With Children’s Physical Activity, Sedentary Time, and Screen Time by Socioeconomic Status,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 9, no. 1 (2012): 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. M. Tremblay, A. LeBlanc, M. Kho, et al., “Systematic Review of Sedentary Behaviour and Health Indicators in School-Aged Children and Youth,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 8, no. 1 (2011): 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10. See, for instance, G. Mitman, “Hay Fever Holiday: Health, Leisure, and Place in Gilded-Age America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 77, no. 3 (2003): 600–635; and C.B. Valencius, “Gender and the Economy of Health on the Santa Fe Trail,” Osiris 19 (2004): 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11. R. Apple, Vitamania: Vitamins in American culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996); C. Warren, “The Gardener in the Machine: Biotechnological Adaptations for Life Indoors,” in V. Berridge and M. Gorsky, eds., Environment, Health, and History (London, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 206–223.

- 12. G. Mitman, “In Search of Health: Landscape and Disease in American Environmental History,” Environmental History 10, no. 2 (2005): 184–210.

- 13. See for example, C. Connolly, Saving Sickly Children: The Tuberculosis Preventorium in American Life, 1909–1970 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008); Guarneri, “Changing Strategies for Child Welfare”; D. Cavallo, Muscles and Morals: Organized Playgrounds and Urban Reform, 1880–1920 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981); M. Crnic and C. Connolly, “‘They Can’t Help Getting Well Here’: Seaside Hospitals for Children in the United States, 1872–1917,” Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 2, no. 2 (2009): 220–233. Although they were closely related to fresh air programs, hospitals used nature to treat children with active, and often chronic, noncontagious medical conditions, rather than focus on prevention and social intervention.

- 14. When children develop tuberculosis, it most often appears in the joints and spine rather than in the lungs, as it does in adults.

- 15. R. Meckel, Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929; G. Condran and J. Murphy, “Defining and Managing Infant Mortality: A Case Study of Philadelphia, 1870–1920,” Social Science History 32, no. 4 (2008): 473–513.

- 16. F. Tisdall, “Sunlight and Health,” American Journal of Public Health 16, no. 7 (1926): 694–699, 695 (quotation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17. Ibid., 698.

- 18. Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Managers of the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA: Printing House of Allen, Lane and Scott; 1902), 5.

- 19.Tenth Annual Report of the Managers of the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, AP: Allen, Lane and Scott’s Publishing House; 1887. pp. 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Managers of the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia, 14.

- 21. Ibid., 9.

- 22. Ibid., 14.

- 23.Thirty-Eighth Annual Report of the Managers of the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, PA: Allen, Lane and Scott; 1913. pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Second Report of the Managers of the Free Sanitarium for Sick Children at Point Airy (Philadelphia, PA: James E. Kryder, Printer, 1878), 10.

- 25. For another perspective on the Sanitarium Association, see Condran and Murphy, “Defining and Managing Infant Mortality,” 491–494.

- 26. Twenty-Fifth Annual Report of the Managers of the Sanitarium Association of Philadelphia,11.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. “The Children’s House, NE. Cor South Caroline and Pacific Avenues, Atlantic City, N.J,” no page. The annual reports for the Children’s Seashore House can be found at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. They vary in title and publication information, so for convenience they will be referred to as “CSH Annual Report for [year].”.

- 29. CSH Annual Report for 1875,15; back cover.

- 30. The Annual Reports often included lists of diseases of patients. See, for instance, CSH Annual Report for 1887, 6.

- 31. CSH Annual Report for 1911, 15.

- 32. CSH Annual Report for 1875, 15.

- 33. For instance, see [Stockman, 7/28/1919], [Patient Register—Cottages 1920–1924], MSS 6/0013-02, Children’s Seashore House Records, 1872–1998, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Historical Medical Library; [Steer, 8/22/1919], [Patient Register—Cottages 1920–1924], MSS 6/0013-02, Children’s Seashore House Records, 1872–1998, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Historical Medical Library.

- 34. In addition to the annual reports, see Crnic and Connolly, “They Can’t Help Getting Well Here.”.

- 35. L. Hill, J. A. Campbell, and H. Gauvain, “Metabolism of Children Undergoing Open-Air Treatment, Heliotherapy and Balneotherapy,” British Medical Journal 1 no. 3191 (1922): 301–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. R. Hammond, “Treatment of Bone Tuberculosis at The Crawford Allen Hospital,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 165 (July 13, 1911): 49–51.

- 37. B. Reed, “The Effects of Sea Air Upon Diseases of the Respiratory Organs, Including a Study of the Influence Upon Health of Changes in the Atmospheric Pressure,” The American Climatological Association 1 (1884): 51–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. G. Oliver, “The Therapeutics of the Sea-Side: With Special Reference to the North-East Coast,” British Medical Journal 2, no. 516 (1870): 550–551; W. B. Stewart, “Influence of Sea-Air and Sea-Water Baths on Disease,” Journal of the American Medical Association 35, no. 11 (1900): 678–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39. For instance, Coney Island’s Sea Breeze Hospital closed for good in 1943, and the Boston Floating Hospital moved its operations on-land in 1931.

- 40.Shearer T. M. Two Weeks Every Summer: Fresh Air Children and the Problem of Race in America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 41. M. F. Ditmar, “Requiem for a Hospital,” Pediatrics 88, no. 2 (1991): 286–289. [PubMed]

- 42. On changing ideologies in medicine and the rise of germ theory, see J.H. Warner, The Therapeutic Perspective: Medical Knowledge, Practice, and Identity in America, 1820–1885 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986); The Therapeutic Revolution: Essays in the Social History of American Medicine, ed. M.J. Vogel and Charles Rosenberg (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1979); N. Tomes, Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998).

- 43. C. Sellers, “To Place or Not to Place: Toward an Environmental History of Modern Medicine,” Bulletin History of Medicine 92 (2018): 1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. R. I. Harris, “Heliotherapy in Surgical Tuberculosis,” American Journal of Public Health 16, no. 7 (1926): 687–694, 693 (quotation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45. Ibid.

- 46. Apple, Vitamania.

- 47. C. Sellers, “To Place or Not to Place.” Even these fields depended on the laboratory for their expertise. See C. Sellers, “The Dearth of the Clinic: Lead, Air, and Agency in Twentieth Century America,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 58, no. 3 (2003): 255–291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48. Three major health care groups within the United States have provided early leadership in the nature prescription movement, namely, Unity Health Care in Washington, DC; Boston Medical Center in Boston, MA; and Healthy Parks Health People Bay Area in California’s San Francisco Bay Area. These groups have pioneered collaborations with partners from local to national levels, in the public, private, and nonprofit sectors.

- 49.Nash L. Inescapable Ecologies: A History of Environment, Disease, and Knowledge. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 50. H. Frumkin, G. Bratman, S. Breslow, et al., “Nature Contact and Human Health: A Research Agenda,” Environmental Health Perspectives 125, no. 7 (2017): 075001; M.C. Kondo, J. Fluehr, T. McKeon, et al., “Urban Green Space and its Impact on Human Health,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 3 (2018): 445; D. Shanahan, R. Fuller, R. Bush, et al., “The Health Benefits of Urban Nature: How Much Do We Need?” BioScience 65, no. 5 (2015): 476–485.

- 51. M. Söderström, C. Boldemann, U. Sahlin, et al., “The Quality of the Outdoor Environment Influences Childrens Health—A Cross-Sectional Study of Preschools,” Acta Paediatrica 102, no. 1 (2013): 83–91; I. Markevych, E. Thiering, E. Fuertes, et al., “A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Effects of Residential Greenness on Blood Pressure in 10-Year Old Children: Results From the GINIplus and LISAplus Studies,” BMC Public Health 14, no. 1 (2014): 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52. Christian et al., “Influence of the Neighborhood Physical Environment on Early Child Health and Development”; Lovasi et al., “Is the Environment Near Home and School Associated With Physical Activity and Adiposity of Urban Preschool Children?”.

- 53. F. Taylor and F. Kuo, “Children With Attention Deficits Concentrate Better After Walk in the Park,” Journal of Attention Disorders 12, no. 5 (2009): 402–409; F. Taylor, F. Kuo, and W. Sullivan, “Coping With ADD: The Surprising Connection to Green Play Settings,” Environment and Behavior 33, no. 1 (2001): 54–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54. G. Evans and P. Kim, “Childhood Poverty, Chronic Stress, Self-Regulation, and Coping,” Child Development Perspectives 7, no. 1 (2013): 43–48; R. Jackson, J. Tester, and S. Henderson, “Environment Shapes Health, Including Children’s Mental Health,” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 47, no. 2 (2008): 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55. V. Rideout, U. Foehr, and D. Roberts, Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-Year Olds (Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009).

- 56. R. Troiano, D. Berrigan, K. Dodd, et al., “Physical Activity in the United States Measured by Accelerometer.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40, no. 1 (2008): 181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57. L. Kann, T. McManus, W. Harris, et al., “Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2015,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries 65, no. SS-6 (2016): 1–174. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58. For instance, the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s pediatric population has an obesity rate of 55% compared with approximately 16% among children in the United States.

- 59. A. Tate, “Urban Parks in the Twentieth Century,” Environment and History 24 (2018): 81–101.

- 60. B. Cutts, K. Darby, C. Boone, and A. Brewis, “City Structure, Obesity, and Environmental Justice: An Integrated Analysis of Physical and Social Barriers to Walkable Streets and Park Access,” Social Science & Medicine 69 (2009): 1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61. A. Brownlow, “An Archaeology of Fear and Environmental Change in Philadelphia,” Geoforum 37, no. 2 (2006): 227–245.

- 62. Philadelphia Parks Alliance, “Philadelphia Parks & Recreation by the Numbers 2014,” https://phila-parks-fr83.squarespace.com/s/FINAL-PPR-by-the-Numbers_4_10_2014-mhxg.pdf (accessed July 10, 2019)

- 63.Safety in Philadelphia Parks and Recreation Centers. Philadelphia, PA: City of Philadelphia Commission on Parks and Recreation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livingston G. “About One Third of US Children Are Living With an Unmarried Parent,” April 25, 2018, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/04/25/the-changing-profile-of-unmarried-parents (accessed July 10, 2019); L. Gordon and S. McLanahan, “Single Parenthood in 1900,” Journal of Family History 16, no. 2 (1991): 97–116.

- 65. E. Pollack, “The Childhood We Have Lost: When Siblings Were Caregivers,” Journal of Social History 36, no. 1 (2002): 31–61.

- 66.Hamblin J. “The Nature Cure: Why Some Doctors Are Writing Prescriptions for Time Outdoors,” The Atlantic, October 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/10/the-naturecure/403210 (accessed August 13, 2018)