Abstract

Objectives. To test the efficacy of Me & You, a multilevel technology-enhanced adolescent dating violence (DV) intervention, in reducing DV perpetration and victimization among ethnic-minority early adolescent youths. We assessed secondary impact for specific DV types and psychosocial outcomes.

Methods. We conducted a group-randomized controlled trial of 10 middle schools from a large urban school district in Southeast Texas in 2014 to 2015. We used multilevel regression modeling; the final analytic sample comprised 709 sixth-grade students followed for 1 year.

Results. Among the total sample, odds of DV perpetration were lower among intervention students than among control students (adjusted odds ratio = 0.46; 95% confidence interval = 0.28, 0.74). Odds of DV victimization were not significantly different. There were significant effects on some specific DV types.

Conclusions. Me & You is effective in reducing DV perpetration and decreasing some forms of DV victimization in early middle-school ethnic-minority students.

Adolescent dating violence (DV) includes physical, psychological (including emotional), and sexual violence, and stalking. Some DV types (e.g., psychological, sexual) can happen in person or via technology.1 Though likely underestimates,2 nationally, approximately 7% to 8% of high-school adolescents experience physical and sexual DV.3 Some studies suggest African American and Hispanic youths are more likely to experience DV.4–6 Although more research is needed to explain these disparities, neighborhood economic disadvantage, as well as racial and gender discrimination, may be contributing factors.7–9 DV consequences include suicidal ideation, substance use, depression,10,11 and adult domestic violence,12 with physical, mental, and economic costs,13,14 emphasizing the need for prevention.

Dating often begins in middle school (sixth to eighth grade, ages 11 to 14 years).15,16 In a recent study, almost 50% of predominantly urban ethnic-minority sixth graders reported ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend.16 Middle-school dating coincides with puberty onset,17,18 when youths may lack cognitive skills (e.g., problem solving, managing emotions)19,20 for healthy dating.19 In sixth grade, almost half of urban dating youths (80% African American, 15% Hispanic) reported being physically or emotionally victimized by a dating partner during the past 3 months (race/ethnicity of their perpetrators was not reported); one third reported perpetrating DV.15 Furthermore, DV increased from sixth to eighth grade. Interventions that develop cognitive skills for maintaining healthy dating relationships, particularly among ethnic-minority sixth graders, are needed. In addition, DV is influenced by multiple socioecological levels (e.g., students, parents, school), making multilevel interventions needed.21

Some multilevel middle-school interventions have demonstrated DV reductions (e.g., Shifting Boundaries, Expect Respect, It’s Your Game . . . Keep It Real [IYG], Safe Dates, Families for Safe Dates),22–26 including some among predominantly ethnic-minority youths. However, the majority were developed for mixed middle- and high-school grades, so they may not be developmentally appropriate for early adolescents. In addition, only 1 intervention24 utilizes technology beyond videos, a limitation because technology facilitates tailored education, greater enjoyment, and interactivity.27

To address these gaps, we adapted IYG, a multimedia seventh- and eighth-grade sexual health and healthy relationships intervention28,29 shown to reduce emotional DV perpetration and victimization and physical DV victimization24 among urban ethnic-minority youths. Compared with IYG, which included 2 healthy relationship lessons, the adapted intervention, Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships (Me & You), focuses exclusively on promoting healthy relationships and preventing DV, is more developmentally appropriate for sixth graders, directly addresses determinants (e.g., conflict resolution skills and norms toward violence) of physical DV perpetration,5,30–32 and includes DV prevention activities for parents and school personnel. We tested the efficacy of Me & You in reducing DV perpetration and victimization among urban ethnic-minority youths. We hypothesized that odds of DV would be lower among students who received Me & You than among students who did not receive Me & You.

METHODS

We conducted a group-randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of Me & You in reducing DV in a large urban southeast Texas school district. We approached 13 middle schools not currently receiving IYG. Ten agreed to participate. We randomized 5 to intervention and 5 to comparison by using a multiattribute randomization protocol33 accounting for school type (e.g., magnet), region, race/ethnicity, sixth-grade enrollment, percentages of economically disadvantaged students, and students “at risk” for drop out. Schools identified a contact to help with logistics.

All sixth graders who were enrolled in health or physical education, spoke English, and were not enrolled in special education were eligible. Staff described the project to youths in class; information was sent home to parents, with follow-up packets to nonrespondents. Students received a $5 gift card for returning a parent consent regardless of consent status; additional $5 gift cards for completing the baseline and first follow-up survey (immediate postintervention; 2.5 months after baseline), respectively; and a $10 gift card for completing the second follow-up survey (12 months after baseline). Parental consent and student assent were obtained before baseline. Students without parental consent participated in regular classroom activities.

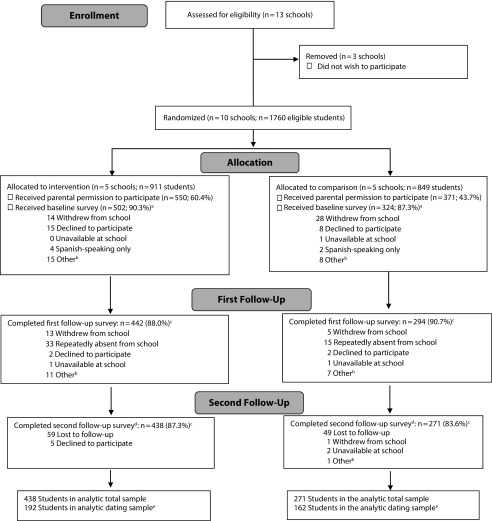

Of 1760 eligible students, 921 (52.3%) received parental consent (Figure 1). Of these, 826 (89.7%) completed baseline surveys in early spring 2014. Of these, 736 (79.9%) completed first follow-up surveys in late spring 2014, and 709 (77.0%) completed second follow-up surveys in spring 2015. Students in the follow-up sample were more likely to be male, younger, and Hispanic. Attrition was nondifferential across conditions.

FIGURE 1—

Flow of Study Participants: Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships, Southeast Texas, 2014 to 2015

aDenominator includes students who received parental permission to participate.

b“Other” indicates incomplete or missing or damaged surveys.

cDenominator includes students who completed baseline surveys.

dStudents who completed a baseline survey may have missed the first follow-up survey but completed the second follow-up survey. Thus, the numbers in the second follow-up survey box equal the number of students who completed a baseline survey.

eDating analytic sample comprises students who reported ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend at baseline.

Intervention Description

We used intervention mapping, a systematic theory- and evidence-based instructional design approach, to inform adaptation.34,35 As with IYG, Me & You is grounded in social–cognitive theories36,37 and socioemotional learning,38 but also the socioecological model.39 We modified IYG objectives, which focused on promoting healthy relationships (in general) to explicitly address all unhealthy relationship behavior types (i.e., emotional, physical, sexual, cyber). Previous formative work28 and adolescent advisory board input informed program design. To enhance relevance for the priority population, Me & You addressed surface- (e.g., music, settings, clothing) and deep- (e.g., respect for and inclusion of family, inclusion of ethnic-minority peer role models) structure cultural features.40 In addition, we included both genders as potential perpetrators and victims41 and gender-neutral names (when possible) to promote inclusivity.

The student component comprises 13 lessons that each last 25 minutes delivered by trained facilitators: 5 classroom (including interactive role plays, group discussion, and other skill-building activities), 5 individual computer only, and 3 classroom–computer blended (delivered in class, with some group-based computer activities). Computer activities included animations, peer video role modeling of skilled behaviors, interactive quizzes, and virtual role-play skills practice. Selected activities were tailored by user characteristics. For example, quizzes about communication provided tailored feedback based on users’ answers. During virtual role-plays, students selected their partner’s gender to increase relevance of activities to youths with same-gender partners.

We adapted IYG’s life-skills decision-making paradigm (select, detect, protect),28,29,36,37 to promote healthy relationships in sixth grade. The goal was to increase skills for decision-making in relationships, understanding the consequences of one’s actions, and solving problems. Students were instructed to select personal rules to have healthy friendships and dating relationships, to detect signs and situations that could challenge rules, and to protect their rules.

Additional topics (not included in IYG) covered modeling and skills practice for managing emotions and constructive communication skills, DV types and consequences, unfavorable norms toward violence, active consent, power differentials, gender-role stereotypes, general online safety, cyber DV, and sexting, and resources to leave unhealthy relationships. Lessons emphasized that skills could be applied to any current or future relationship (e.g., peers, dating partners, family) to ensure material was relevant to students not currently dating. The intervention emphasized perceived norms of students not needing a boyfriend or girlfriend. Sexual DV scenarios and activities were limited to age-appropriate presexual behaviors (e.g., kissing, holding hands).

Selected activities (e.g., managing emotions, consent, DV definitions, power differentials, cyber abuse) were pilot-tested with an adolescent advisory board comprising 15 ethnically diverse (African American, Asian, and Hispanic) students (11 boys, 4 girls) to ensure language and scenarios were realistic and relevant to urban ethnic-minority youths.35

The parent component comprises 3 parent–child take-home activities and 2 parent newsletters. Take-home activities included interactive discussions to promote parent–child communication about dating expectations, characteristics of healthy friendships and dating relationships, communication skills, and strategies for getting out of unhealthy relationships. Facilitators debriefed these take-home activities with students in class. Newsletters included tips, interactive games, and “ask-the-expert” Q&A. Topics included DV definitions, warning signs of unhealthy relationships, strategies for increasing DV awareness, enhancing parent–child communication and connectedness, online safety, and linking parents to resources.

The school component comprises a 2-day teacher training and 1 school newsletter (delivered during lesson 1). Along with instruction on fidelity and effective teaching, teachers were instructed on how to recognize DV, respond to students involved in DV, and refer students to appropriate resources. The newsletter was emailed to all school staff. Topics included DV types, unhealthy relationship behaviors, importance of addressing DV in schools, and “recognize–respond–refer.”

Intervention Implementation

Implementation of Me & You occurred in spring 2014. To ensure sufficient teaching coverage, 8 research staff and 4 teachers were trained. The computer-based application was installed on intervention school computers. Research staff worked with school personnel to identify subjects suitable for Me & You delivery (e.g., physical education, health, science). Before implementation, parents received passive consent forms. Comparison schools received their regular health education from the state-approved textbook; school contacts confirmed that no comparison school received any evidence-based DV education. Intervention students received Me & You instead of regular health education when the curriculum was implemented in physical education and health.

Data Collection

Data were collected through computer-assisted self-interviews (no audio) on school computers during regular classes by using an Internet-based survey (Qualtrics, Qualtrics XM, Provo, Utah) hosted on a secure institutional server. Data collectors were available for questions.

Dating Violence Measures

We used the Conflict in Adolescent Dating and Relationship Inventory (CADRI)42 to assess physical DV (4 items; e.g., “I threw something at him/her”), verbal or emotional DV (10 items; e.g., “I insulted him/her with put-downs”), relational DV (3 items; e.g., “I spread rumors about him/her”), threatening behavior (4 items; e.g., “I threatened to hit him/her or throw something at him/her), and sexual DV (1 item; “I kissed him/her when he/she did not want me to”). Per previous studies, “verbal/emotional DV” comprised verbal or emotional and relational DV subscales42 and was labeled as “psychological” for this study. Only 1 sexual DV subscale item was used to match Me & You developmental content. The CADRI demonstrated adequate reliability (α > 0.70 for all subscales, with exception of threatening perpetration [α = 0.65]). Cyber DV perpetration and victimization were assessed with a 13-item scale (α > 0.80; e.g., “I posted embarrassing photos or other images of him/her online”).43,44

Participants were asked about lifetime exposure at baseline and past-12-months’ exposure at second follow-up. DV questions were not asked at the first follow-up, given insufficient time for behavior change. DV questions were asked twice—related to perpetration and then victimization—with dichotomous response options (yes, no). Participants who indicated 1 or more behaviors (i.e., physical, sexual, cyber) were classified as perpetrator or victim for that specific type. Because of its high prevalence, the threshold for psychological DV was higher (3 or more behaviors).45 We created 2 DV composite variables (perpetration and victimization). Because the CADRI was originally tested among high-school students, items were pilot-tested with our adolescent advisory board to ensure comprehension with minor wording changes recommended (e.g., changing “deliberately” to “on purpose”).

Primary dating violence outcomes.

The primary outcome measures were DV perpetration and victimization in the total (dating and nondating) sample. DV was a dichotomous variable, categorized as participation in 1 or more DV types (physical, psychological, threatening, sexual, or cyber) versus no participation in any types. Only students who indicated ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend (defined as “someone that you have dated, gone out with, or gone steady with”) answered DV questions. However, consistent with previous studies,46 and because the intervention emphasized perceived norms related to students (especially sixth graders) not needing a boyfriend or girlfriend, students who reported not ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend were coded as not having participated in any DV perpetration or victimization and were included in the primary outcome analysis.

Secondary dating violence outcomes.

Secondary outcomes assessed impact on DV perpetration and victimization in the “dating” sample, which comprised students who reported ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend. Furthermore, we assessed impact on each type (physical, emotional, threatening, cyber, or sexual) of DV perpetration and victimization for the total sample and dating sample. We created dichotomous variables for each DV type (participation vs no participation).

Psychosocial Measures

Using reliable and valid measures, we assessed theory-based36,39 determinants of DV including individual (norms toward boy-against-girl violence and girl-against-boy violence,47,48 self-efficacy to resolve conflict,49 communication skills,47,50 attitudes toward sexting,51 belief in need for help,25 and coping52,53), perceived peer DV, family (parent–child communication,54 closeness55), and community (social support56) psychosocial factors. Detailed measurement information is provided in the Appendix (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

Process Measures

To assess program coverage, facilitators completed attendance and fidelity logs for each Me & You class to document implementation, adaptations, and challenges. Students were asked to return a parental-signed activity slip following completion of each take-home activity. Attendance data were collected from 420 of 502 intervention students. Of these, approximately 70% received 10 or more lessons (three quarters of all lessons); 68% received at least 4 of 5 computer lessons. Fidelity logs indicated that approximately 59% of lessons included all planned activities; 18% included some but not all planned activities, and 23% had incomplete fidelity information. Low return rates for the take-home activity slips limited fidelity data for this component. However, facilitator discussion of take-home activities occurred in 57% of appropriate lessons. Budgetary constraints precluded process data collection from parents and school personnel.

Data Analysis

Preliminary analysis of baseline data for the total (dating and nondating) and dating samples provided profiles for demographics and baseline outcome characteristics. We adjusted for imbalances between study groups and potential confounding variables in all models. Student observations within the same school cannot be assumed to be independent. We used multilevel logistic and linear regression modeling to account for any intraclass correlation. Each model contained baseline measures of the dependent variable, where appropriate, adjusting for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and time between assessments. We entered a dichotomous variable indicating treatment condition into each model to assess intervention effects. We used the Wald statistic (i.e., the ratio of the regression parameter to its standard error) to test for statistical significance. Intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.000 to 0.022 across outcomes. We analyzed primary and secondary DV outcomes at the second follow-up to allow time for behavior change; we analyzed psychosocial outcomes at first and second follow-up.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes baseline characteristics of the total and dating analytic samples. In the total sample, age, ever having a boyfriend or girlfriend, DV victimization, psychological DV perpetration and victimization, physical DV victimization, and 2 psychosocial variables were significantly different across conditions. In the “dating” sample, age and 1 psychosocial variable were significantly different.

TABLE 1—

Comparability of Intervention and Comparison Conditions Among the Total and Dating Analytic Samples at Baseline: Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships, Southeast Texas, 2014 to 2015

| Total Analytic Sample,a %, Mean (SD), or Range | Dating Analytic Sample,b %, Mean (SD), or Range | |||||

| Total (n = 709) | Intervention (n = 438) | Comparison (n = 271) | Total (n = 354) | Intervention (n = 192) | Comparison (n = 162) | |

| Characteristics (demographic and behavior) | ||||||

| Female | 52.5 | 54.6 | 49.1 | 42.9 | 45.0 | 40.4 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| African American | 21.0 | 18.3 | 25.5 | 27.4 | 24.5 | 30.9 |

| Hispanic | 71.1 | 73.5 | 67.2 | 64.1 | 67.2 | 60.5 |

| Other | 7.9 | 8.2 | 7.4 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 8.6 |

| Age, y | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.2 (0.59) | 12.2 (0.56)** | 12.3 (0.61) | 12.4 (0.62) | 12.3 (0.57)** | 12.4 (0.67) |

| Range | 11.17–14.54 | 11.19–14.52 | 11.17–14.54 | 11.23–14.54 | 11.31–14.52 | 11.23–14.54 |

| Ever had a boyfriend or girlfriend, yes | 50.4 | 44.1** | 60.4 | . . . | . . . | . . . |

| Ever perpetratedc | ||||||

| DV | 23.7 | 21.5 | 27.4 | 49.4 | 51.1 | 47.3 |

| Physical DV | 12.8 | 11.9 | 14.2 | 25.8 | 27.4 | 23.9 |

| Psychological DV | 28.1 | 24.4** | 34.4 | 57.5 | 56.5 | 58.7 |

| Threatening DV | 8.7 | 8.2 | 9.6 | 17.6 | 18.8 | 16.2 |

| Cyber DV | 6.8 | 5.6 | 8.7 | 13.9 | 13.0 | 14.9 |

| Sexual DV | 4.3 | 3.2 | 6.1 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 10.1 |

| Ever victimizedc | ||||||

| DV | 23.1 | 19.7* | 28.7 | 48.3 | 46.6 | 50.4 |

| Physical DV | 10.8 | 8.9* | 13.9 | 21.8 | 20.4 | 23.5 |

| Psychological DV | 27.4 | 24.2* | 32.7 | 56.0 | 56.3 | 55.6 |

| Threatening DV | 7.9 | 7.4 | 8.7 | 16.1 | 17.1 | 14.9 |

| Cyber DV | 7.8 | 7.3 | 8.7 | 16.2 | 17.1 | 15.1 |

| Sexual DV | 7.6 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 15.2 |

| Psychosocial measuresd | ||||||

| Norms for boy-against-girl violence | 7.86 (3.03) | 7.76 (3.06) | 8.01 (2.98) | 7.99 (3.28) | 8.02 (3.45) | 7.95 (3.08) |

| Norms for girl-against-boy violence | 7.27 (3.26) | 7.17 (3.30) | 7.43 (3.20) | 7.47 (3.41) | 7.63 (3.50) | 7.28 (3.29) |

| Self-efficacy to resolve conflict | 4.04 (0.96) | 4.11* (0.85) | 3.92 (1.10) | 3.85 (1.02) | 3.91 (0.93) | 3.77 (1.12) |

| Constructive conflict-resolution skills | 1.51 (0.84) | 1.49 (0.84) | 1.54 (0.85) | 1.54 (0.85) | 1.54 (0.83) | 1.55 (0.87) |

| Destructive conflict-resolution skills | 0.87 (0.68) | 0.84 (0.63) | 0.92 (0.75) | 0.95 (0.71) | 0.93 (0.67) | 0.97 (0.76) |

| Attitudes about sexting | 1.35 (0.85) | 1.26** (0.74) | 1.50 (0.98) | 1.43 (0.93) | 1.32* (0.81) | 1.56 (1.05) |

| Belief in the need for help | 4.12 (1.25) | 4.19 (1.20) | 4.01 (1.32) | 4.03 (1.26) | 4.12 (1.22) | 3.92 (1.29) |

| Peer dating violence perpetration | 1.37 (0.73) | 1.34 (0.67) | 1.44 (0.82) | 1.44 (0.80) | 1.40 (0.71) | 1.49 (0.90) |

| Parent–child communication about relationships | 0.75 (0.64) | 0.77 (0.63) | 0.73 (0.66) | 0.79 (0.65) | 0.83 (0.62) | 0.73 (0.69) |

| Parent–child closeness | 3.90 (0.96) | 3.95 (0.91) | 3.82 (1.04) | 3.82 (1.02) | 3.90 (0.96) | 3.73 (1.08) |

| Positive coping strategies | 72.5 | 72.9 | 71.5 | 71.8 | 74.5 | 68.6 |

| Social support | 92.3 | 92.7 | 91.7 | 91.4 | 93.4 | 89.1 |

Note. DV = dating violence.

The total sample includes both daters and nondaters. Furthermore, sample sizes for individual analyses vary because of missing data.

Sample sizes for individual analyses vary because of missing data.

DV was a dichotomous variable and categorized as participation in 1 or more DV types (physical, psychological, threatening, sexual, or cyber) versus no participation in any types. Dichotomous variables were created for each specific DV type (participation vs no participation).

All psychosocial variables are coded as risk factors, except for self-efficacy to resolve conflict, constructive conflict-resolution skills, belief in the need for help, parent–child communication about relationships, parent–child closeness, positive coping strategies, and social support.

P < .05; **P < .01.

Dating Violence Behaviors

Among the total sample, odds of DV perpetration in the past 12 months were lower among intervention students than comparison students (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.46; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.28, 0.74; Table 2). However, odds of DV victimization were not significantly different between conditions. Regarding specific DV types, odds of physical DV perpetration (AOR = 0.35; 95% CI = 0.19, 0.66), psychological DV perpetration (OR = 0.62; 95% CI = 0.41, 0.96), threatening DV perpetration (AOR = 0.33; 95% CI = 0.15, 0.71) and victimization (AOR = 0.36; 95% CI = 0.17, 0.78), and sexual DV victimization (AOR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.11, 0.94) were lower among intervention students than comparison students. Among the dating sample, intervention effects were similar, except for psychological DV perpetration, threatening DV victimization, and sexual DV victimization.

TABLE 2—

Intervention Effects on Dating Violence Perpetration and Victimization at Second Follow-Up Among the Total and Dating Analytic Samples: Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships, Southeast Texas, 2014 to 2015

| Total Analytic Samplea | Dating Analytic Sample | |||||||

| No.b | Intervention,c % Yes | Comparison,c % Yes | AOR (95% CI) | No.b | Intervention,c % Yes | Comparison,c % Yes | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Ever perpetrated | ||||||||

| DV | 641 | 11.0 | 21.5 | 0.46 (0.28, 0.74) | 299 | 19.7 | 28.4 | 0.50 (0.28, 0.90) |

| Physical DV | 671 | 5.1 | 12.5 | 0.35 (0.19, 0.66) | 328 | 8.5 | 15.6 | 0.39 (0.18, 0.83) |

| Psychological DV | 658 | 18.2 | 28.7 | 0.62 (0.41, 0.96) | 317 | 30.3 | 38.8 | 0.60 (0.33, 1.07) |

| Threatening DV | 668 | 3.0 | 8.3 | 0.33 (0.15, 0.71) | 323 | 4.8 | 10.2 | 0.30 (0.11, 0.79) |

| Cyber DV | 662 | 2.8 | 6.4 | 0.57 (0.25, 1.29) | 317 | 4.8 | 8.9 | 0.55 (0.22, 1.42) |

| Sexual DV | 683 | 1.9 | 4.1 | 0.49 (0.18, 1.34) | 336 | 3.7 | 6.2 | 0.58 (0.19, 1.73) |

| Ever victimized by | ||||||||

| DV | 634 | 11.9 | 21.0 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.01) | 296 | 21.9 | 30.2 | 0.68 (0.38, 1.22) |

| Physical DV | 668 | 5.3 | 8.8 | 0.64 (0.33, 1.26) | 322 | 10.0 | 12.3 | 0.76 (0.35, 1.63) |

| Psychological DV | 661 | 19.8 | 26.1 | 0.66 (0.39, 1.10) | 318 | 33.5 | 36.0 | 0.73 (0.45, 1.20) |

| Threatening DV | 664 | 3.3 | 7.6 | 0.36 (0.17, 0.78) | 319 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 0.52 (0.22, 1.25) |

| Cyber DV | 647 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 0.51 (0.23, 1.12) | 305 | 5.4 | 10.7 | 0.42 (0.16, 1.06) |

| Sexual DV | 680 | 3.7 | 8.6 | 0.32 (0.11, 0.94) | 333 | 6.9 | 12.0 | 0.42 (0.18, 1.00) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DV = dating violence. All models adjusted for baseline value of dependent variable, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and time between assessments. DV was a dichotomous variable and categorized as participation in 1 or more DV types (physical, psychological, threatening, sexual, or cyber) versus no participation in any types. Dichotomous variables were created for each specific DV type (participation vs no participation).

The total sample includes both daters and nondaters.

Sample sizes reflect those used for the adjusted models and vary because of missing data.

Unadjusted percentages.

Psychosocial Outcomes

Among the total sample, at first follow-up, intervention students reported less-favorable norms for boy-against-girl violence and girl-against-boy violence, greater constructive conflict-resolution skills, and more negative attitudes about sexting compared with comparison students (Table 3). At second follow-up, intervention effects on norms toward boy-against-girl violence and girl-against-boy violence remained statistically significant. Among the dating sample, at first follow-up, no psychosocial factors were statistically significant; at second follow-up, norms for girl-against-boy violence were statistically significant.

TABLE 3—

Intervention Effects on Psychosocial Outcomes at First and Second Follow-Up Among the Total and Dating Analytic Samples: Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships, Southeast Texas, 2014 to 2015

| Outcomea (Score Range) | Total Analytic Sample,b Immediate | Total Analytic Sample,b 12-Month Follow-up | Dating Analytic Sample, Immediate | Dating Analytic Sample, 12-Month Follow-up | ||||

| No.c | Adjusted Mean Differenced (SE) or AOR (95% CI) | No.c | Adjusted Mean Differenced (SE) or AOR (95% CI) | No.c | Adjusted Mean Differenced (SE) or AOR (95% CI) | No.c | Adjusted Mean Differenced (SE) or AOR (95% CI) | |

| Norms for boy-against-girl violence (6–24) | 592 | −0.64 (0.26) | 659 | −0.44 (0.20) | 286 | −0.68 (0.35) | 324 | −0.48 (0.29) |

| Norms for girl-against-boy violence (4–16) | 574 | −0.93 (0.28) | 653 | −0.59 (0.23) | 277 | −0.78 (0.42) | 318 | −0.68 (0.31) |

| Self-efficacy to resolve conflict (1–5) | 582 | 0.00 (0.10) | 655 | 0.08 (0.09) | 275 | −0.07 (0.11) | 318 | 0.09 (0.13) |

| Constructive conflict resolution skills (0–3) | 528 | 0.16 (0.07) | 611 | 0.06 (0.06) | 256 | 0.18 (0.10) | 299 | 0.06 (0.09) |

| Destructive conflict resolution skills (0–3) | 544 | −0.02 (0.06) | 611 | −0.07 (0.06) | 262 | 0.06 (0.09) | 291 | −0.04 (0.08) |

| Attitudes about sexting (1–4) | 606 | −0.16 (0.07) | 666 | −0.08 (0.06) | 294 | −0.15 (0.10) | 327 | −0.12 (0.08) |

| Belief in the need for help (1–5) | 574 | 0.03 (0.12) | 640 | −0.02 (0.10) | 276 | −0.06 (0.17) | 308 | 0.11 (0.14) |

| Peer dating violence perpetratione (1–5) | . . . | . . . | 648 | −0.09 (0.05) | . . . | . . . | 314 | −0.17 (0.09) |

| Parent–child communication about relationships (0–2) | 562 | 0.08 (0.09) | 640 | 0.02 (0.05) | 267 | 0.15 (0.09) | 310 | 0.02 (0.07) |

| Parent–child closeness (1–5) | 559 | 0.05 (0.09) | 624 | 0.00 (0.08) | 268 | 0.21 (0.14) | 297 | 0.09 (0.12) |

| Positive coping strategies | 611 | 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) | 680 | 1.16 (0.78, 1.73) | 292 | 0.67 (0.36, 1.25) | 330 | 0.88 (0.50, 1.53) |

| Social support | 608 | 0.79 (−1.12, 0.64) | 666 | 1.05 (0.51, 2.16) | 291 | 0.41 (0.09, 1.92) | 322 | 0.91 (0.32, 2.55) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval. All models adjusted for baseline value of dependent variable, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and time between assessments.

All psychosocial variables are coded as risk factors, except for self-efficacy to resolve conflict, constructive conflict-resolution skills, belief in the need for help, parent–child communication about relationships, parent–child closeness, positive coping strategies, and social support.

The total sample includes both daters and nondaters.

Sample sizes reflect those used for the adjusted models and vary because of missing data.

The adjusted mean difference is estimated from a linear regression model and represents the difference in the adjusted mean score on the scale between the intervention and control conditions adjusted for all other covariates included in the model.

eThis outcome was assessed for the past 12 months only.

DISCUSSION

We tested the efficacy of Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships, a technology-enhanced DV prevention program for early middle-school students, in reducing DV perpetration and victimization. As hypothesized, odds of DV perpetration were significantly lower among students who received Me & You than among students in the comparison group; however, odds of DV victimization were not significantly different. Furthermore, there were significant intervention effects on some specific types of DV perpetration and victimization, but no significant effects on cyber DV perpetration and some other types of DV victimization. Moreover, there were significant effects on several psychosocial variables. Collectively, these findings indicate Me & You as an effective program to reduce DV, particularly perpetration and some types of victimization, among early adolescents.

There are possible explanations for the positive effects of Me & You on DV perpetration and some types of DV victimization. First, Me & You includes 2 primary features from IYG—technology and a decision-making life-skills paradigm—that contributed to the latter’s success.28,29 Systematic reviews have demonstrated the utility of technology-based programs for health education,57,58 suggesting that tailoring, simulated skills practice, and immediate feedback, all present in Me & You, are important technology components. To our knowledge, the only other effective technology-based DV program was developed for and evaluated among high-school students.59 In addition, Me & You uses a life-skills decision-making paradigm to enhance cognitive skills critical for developing healthy relationships.19 These skills also underlie the social–emotional learning framework, which has been shown to foster positive youth outcomes.38 Furthermore, most effects on DV perpetration were consistent across the total and dating samples reflecting the importance and relevance of teaching these skills for all students, regardless of dating status.

Second, Me & You includes activities to reduce favorable norms toward violence and to improve conflict-resolution skills. Both factors, which are associated with reducing DV perpetration, particularly physical types,5,30–32 were affected by Me & You. Though we did not test mediation, it is possible these factors mediated the behavioral effects of Me & You, as reported for Safe Dates.25 Like Safe Dates, which also had an impact on physical DV perpetration, Me & You includes content related to managing emotions and reducing gender-role stereotypes. Deficits in these skills have been linked to physical and combined (physical–emotional–sexual) DV perpetration.5,32,60 Furthermore, both boys and girls were presented as possible perpetrators, necessary messaging for DV prevention.61

Third, Me & You includes parent–child activities designed to increase parent–child connectedness and communication, which are associated with reduced DV perpetration and victimization among youths,62 particularly Hispanic youths.63 It has been suggested that parents of early adolescents receive instruction on effective communication to help their children prepare for dating.62 Although we do not know how many parents and children completed parent–child activities, fidelity logs indicate that some students completed them with their parents. For those students, these activities would have afforded youths (and parents) the opportunity to practice communication and discuss how parents could support adolescents. Similar activities occur in Families for Safe Dates.26 However, Me & You did not have an impact on parent–child communication and parental closeness; thus, the effect of this parental component merits further study.

There are also possible explanations for the limited effects of Me & You on some specific DV types. Regarding cyber DV, Me & You defined this DV type and included activities related to avoiding unsafe behaviors online. Although Me & You demonstrated positive short-term significant effects on attitudes toward sexting, greater emphasis was placed on general safe technology use (e.g., sharing information online) than on avoiding unsafe technology behaviors with a dating partner. Given the prevalence of cyber DV,16 early adolescent DV programs should include skills-practice activities for avoiding cyber DV.

Finally, intervention effects for sexual DV were mixed: there was no impact on perpetration but a positive impact on victimization. On the one hand, lack of impact on sexual DV perpetration may be attributable to limited emphasis on attitudes toward sexual aggression, which is associated with sexual DV perpetration.64 This omission was intentional because Me & You targets sixth graders. Thus, additional emphasis on these topics for early adolescents may be needed. On the other hand, impact on sexual DV victimization may result from inclusion of explicit discussion of active consent and skills training to help students ask for, and provide, active consent for intimate activities (e.g., holding hands, kissing).65,66 Furthermore, Me & You included activities that challenged traditional gender-role stereotypes, portraying both males and females as perpetrators and victims, which is necessary for reducing sexual DV victimization.25 Expect Respect, which also had an impact on sexual DV victimization (and perpetration), included similar activities.23

Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, generalizability may be limited to English-speaking students not enrolled in special education from a large urban school district. Second, though response rates are similar to those in other large urban samples,67 the low response rate may have contributed some selection bias in that students who were more high-risk were less likely to return parental consent forms, also limiting generalizability. Third, although we used a widely used and validated measure of DV, measures are self-reported and, thus, may not capture all youth meanings of DV.68 Fourth, analyses revealed several pretreatment imbalances. However, we controlled for baseline values of all variables that were significantly different between groups. Fifth, some missing and incomplete attendance and fidelity data limited our ability to assess student exposure to all intervention components. Finally, we relied more on research staff compared with school teachers for program implementation. However, similar to other in-person facilitator programs, this intervention could be scaled up with appropriate training and resources.

Conclusions

Ethnic-minority youths who are just beginning middle school are at high risk for experiencing DV. Subsequently, these youths need effective, innovative multilevel interventions to develop cognitive skills necessary for the formation of healthy dating relationships. Our findings indicate that Me & You, a multilevel, technology-enhanced DV prevention program that provides these critical life skills, is effective in reducing DV perpetration and decreasing some forms of DV victimization in early middle-school ethnic-minority students. Future studies are needed to formally assess mediation pathways and moderating effects, particularly by gender and race/ethnicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1R01CE002135).

The authors would like to thank the school district and students who participated in this study, Lionel Santibáñez for his editorial assistance, and Maria E. Fernandez-Esquer, PhD.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The study and its protocol were approved by the UTHealth Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects and the district’s Research Office.

Footnotes

See also De La Rue, p. 1324.

REFERENCES

- 1.Niolon PH, Kearns M, Dills J Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: a technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2019.

- 2.Rothman EF, Xuan Z. Trends in physical dating violence victimization among US high school students, 1999–2011. J Sch Violence. 2014;13(3):277–290. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2013.847377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1991–2017 High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data. 2019. Available at: http://nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 4.Champion H, Wagoner K, Song EY, Brown VK, Wolfson M. Adolescent date fighting victimization and perpetration from a multi-community sample: associations with substance use and other violent victimization and perpetration. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2008;20(4):419–429. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2008.20.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foshee VA, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Reyes HLM et al. What accounts for demographic differences in trajectories of adolescent dating violence? An examination of intrapersonal and contextual mediators. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(6):596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haynie DL, Farhat T, Brooks-Russell A, Wang J, Barbieri B, Iannotti RJ. Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(2):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedina L, Howard DE, Wang MQ, Murray K. Teen dating violence victimization, perpetration, and sexual health correlates among urban, low-income, ethnic, and racial minority youth. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2016;37(1):3–12. doi: 10.1177/0272684X16685249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinchevsky GM, Wright EM. The impact of neighborhoods on intimate partner violence and victimization. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2012;13(2):112–132. doi: 10.1177/1524838012445641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts L, Tamene M, Orta OR. The intersectionality of racial and gender discrimination among teens exposed to dating violence. Ethn Dis. 2018;28(suppl 1):253–260. doi: 10.18865/ed.28.S1.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foshee VA, Reyes HL, Gottfredson NC, Chang LY, Ennett ST. A longitudinal examination of psychological, behavioral, academic, and relationship consequences of dating abuse victimization among a primarily rural sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(6):723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackard DM, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioral and psychological health of male and female youth. J Pediatr. 2007;151(5):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Bunge J, Rothman E. Revictimization after adolescent dating violence in a matched, national sample of youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;60(2):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Max W, Rice DP, Finkelstein E, Bardwell RA, Leadbetter S. The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence Vict. 2004;19(3):259–272. doi: 10.1891/vivi.19.3.259.65767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I et al. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(4):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goncy EA, Farrell AD, Sullivan TN. Patterns of change in adolescent dating victimization and aggression during middle school. J Youth Adolesc. 2018;47(3):501–514. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0715-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peskin MF, Markham CM, Shegog R et al. Prevalence and correlates of the perpetration of cyber dating abuse among early adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(2):358–375. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0568-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herman-Giddens ME, Steffes J, Harris D et al. Secondary sexual characteristics in boys: data from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1058–e1068. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buttke DE, Sircar K, Martin C. Exposures to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and age of menarche in adolescent girls in NHANES (2003–2008) Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(11):1613–1618. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: a period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021(1):1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cascardi M, Avery-Leaf S. Gender differences in dating aggression and victimization among low-income urban middle school students. Partner Abuse. 2015;6(4):383–402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman EF, Bair-Merritt MH, Tharp AT. Beyond the individual level: novel approaches and considerations for multilevel adolescent dating violence prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):445–447. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor BG, Stein ND, Mumford EA, Woods D. Shifting Boundaries: an experimental evaluation of a dating violence prevention program in middle schools. Prev Sci. 2013;14(1):64–76. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reidy DE, Holland KM, Cortina K, Ball B, Rosenbluth B. Evaluation of the Expect Respect support group program: a violence prevention strategy for youth exposed to violence. Prev Med. 2017;100:235–242. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peskin MF, Markham CM, Shegog R, Baumler ER, Addy RC, Tortolero SR. Effects of the It’s Your Game . . . Keep It Real program on dating violence in ethnic-minority middle school youths: a group randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1471–1477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foshee VA, Bauman KE, Ennett ST, Suchindran C, Benefield T, Linder GF. Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program “Safe Dates” using random coefficient regression modeling. Prev Sci. 2005;6(3):245–258. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foshee VA, Naughton Reyes HL, Ennett ST, Cance JD, Bauman KE, Bowling JM. Assessing the effects of Families for Safe Dates, a family-based teen dating abuse prevention program. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(4):349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noar SM, Harrington NG. eHealth Applications. Promising Strategies for Behavior Change. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tortolero SR, Markham CM, Peskin MF et al. It’s Your Game: Keep It Real: delaying sexual behavior with an effective middle school program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(2):169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Markham CM, Tortolero SR, Peskin MF et al. Sexual risk avoidance and sexual risk reduction interventions for middle school youth: a randomized controlled trial. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith-Darden JP, Reidy DE, Kernsmith PD. Adolescent stalking and risk of violence. J Adolesc. 2016;52:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foshee VA, Naughton Reyes HL, Chen MS et al. Shared risk factors for the perpetration of physical dating violence, bullying, and sexual harassment among adolescents exposed to domestic violence. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(4):672–686. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0404-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe DA, Wekerle C, Scott K, Straatman AL, Grasley C. Predicting abuse in adolescent dating relationships over 1 year: the role of child maltreatment and trauma. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113(3):406–415. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graham JW, Flay BR, Anderson Johnson C, Hansen WB, Collins LM. Group comparability: a multiattribute utility measurement approach to the use of random assignment with small numbers of aggregated units. Eval Rev. 1984;8(2):247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernandez ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. Vol 4. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peskin MF, Markham C, Gabay EK . Using intervention mapping to develop “Me & You: Building Healthy Relationships,” a healthy relationship intervention for early middle school students. In: Wolfe DA, Temple JR, editors. Adolescent Dating Violence: Theory, Research, and Prevention. London, England: Academic Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Vol 4. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissberg RP, Durlak JA, Domitrovich CE, Gullotta TP. Social and emotional learning: past, present, and future. In: Durlak J, Domitrovich CE, Weissberg RP, Gullotta TP, editors. Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sallis JF, Owen N. Ecological models of health behavior. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. Vol 3. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. pp. 462–484. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Capaldi DM. Clearly we’ve only just begun: developing effective prevention programs for intimate partner violence. Prev Sci. 2012;13(4):410–414. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman AL. Development and validation of the Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory. Psychol Assess. 2001;13(2):277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zweig JM, Lachman P, Yahner J, Dank M. Correlates of cyber dating abuse among teens. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(8):1306–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Picard P. Tech Abuse in Teen Relationships Study. 2007. Available at: https://www.breakthecycle.org/sites/default/files/pdf/survey-lina-tech-2007.pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

- 45.Choi HJ, Elmquist J, Shorey RC, Rothman EF, Stuart GL, Temple JR. Stability of alcohol use and teen dating violence for female youth: a latent transition analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/dar.12462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(8):692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall JE, Bangdiwala S. Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Prev Med. 2001;32(2):128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orpinas P, Hsieh HL, Song X, Holland K, Nahapetyan L. Trajectories of physical dating violence from middle to high school: association with relationship quality and acceptability of aggression. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(4):551–565. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9881-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dahlberg LL, Toal SB, Swahn M, Behrens CB. Measuring Violence-Related Attitudes, Behaviors, and Influences Among Youths: A Compendium of Assessment Tools. Vol 2. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foshee VA, Benefield TS, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Suchindran C. Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):1007–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strassberg DS, McKinnon RK, Sustaita MA, Rullo J. Sexting by high school students: an exploratory and descriptive study. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(1):15–21. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spirito A, Francis G, Overholser J, Frank N. Coping, depression, and adolescent suicide attempts. J Clin Child Psychol. 1996;25(2):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laslo DE. The relationship between child coping, parent coping and psychosocial adjustment in children and adolescents with acute lymphocytic leukemia, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto; 1998.

- 54.Tharp AT, Noonan RK. Associations between three characteristics of parent–youth relationship, youth substance use, and dating attitudes. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):515–523. doi: 10.1177/1524839910386220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pflieger JC, Vazsonyi AT. Parenting processes and dating violence: the mediating role of self-esteem in low- and high-SES adolescents. J Adolesc. 2006;29(4):495–512. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cauce AM, Felner RD, Primavera J. Social support in high-risk adolescents: structural components and adaptive impact. Am J Community Psychol. 1982;10(4):417–428. doi: 10.1007/BF00893980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Noar SM, Black HG, Pierce LB. Efficacy of computer technology–based HIV prevention interventions: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23(1):107–115. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831c5500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Omaki E, Rizzutti N, Shields W et al. A systematic review of technology-based interventions for unintentional injury prevention education and behaviour change. Inj Prev. 2017;23(2):138–146. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levesque DA, Johnson JL, Welch CA, Prochaska JM, Paiva AL. Teen dating violence prevention: cluster-randomized trial of teen choices, an online, stage-based program for healthy, nonviolent relationships. Psychol Violence. 2016;6(3):421–432. doi: 10.1037/vio0000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reed E, Silverman JG, Raj A, Decker MR, Miller E. Male perpetration of teen dating violence: associations with neighborhood violence involvement, gender attitudes, and percieved peer and neighborhood norms. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):226–239. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taylor B, Joseph H, Mumford E. Romantic relationship characteristics and adolescent relationship abuse in a probability-based sample of youth. J Interpers Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0886260517730566. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mumford EA, Liu W, Taylor BG. Parenting profiles and adolescent dating relationship abuse: attitudes and experiences. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(5):959–972. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kast NR, Eisenberg ME, Sieving RE. The role of parent communication and connectedness in dating violence victimization among Latino adolescents. J Interpers Violence. 2015;31(10):1932–1955. doi: 10.1177/0886260515570750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reyes HL, Foshee VA. Sexual dating aggression across grades 8 through 12: timing and predictors of onset. J Youth Adolesc. 2013;42(4):581–595. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9864-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hickman S, Muehlenhard C. “By the semi-mystical appearance of a condom”: how young women and men communicate sexual consent in heterosexual situations. J Sex Res. 1999;36(3):258–272. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fantasia HC, Sutherland MA, Fontenot H, Ierardi JA. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about contraceptive and sexual consent negotiation among college women. J Forensic Nurs. 2014;10(4):199–207. doi: 10.1097/JFN.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Langley A, Kataoka SH, Wilkins WS, Wong M. Active parental consent for a school-based community violence screening: comparing distribution methods. J Sch Health. 2007;77(3):116–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith J, Mulford C, Latzman NE, Tharp AT, Niolon PH, Blachman-Denner D. Taking stock of behavioral measures of adolescent dating violence. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2015;24(6):674–692. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1049767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]