Abstract

One of the most pressing unmet challenges for preventing and controlling epidemic obesity is ensuring that socially disadvantaged populations benefit from relevant public health interventions. Obesity levels are disproportionately high in ethnic minority, low-income, and other socially marginalized US population groups. Current policy, systems, and environmental change interventions target obesity-promoting aspects of physical, economic, social, and information environments but do not necessarily account for inequities in environmental contexts and, therefore, may perpetuate disparities.

I propose a framework to guide practitioners and researchers in public health and other fields that contribute to obesity prevention in identifying ways to give greater priority to equity issues when undertaking policy, systems, and environmental change strategies. My core argument is that these approaches to improving options for healthy eating and physical activity should be linked to strategies that account for or directly address social determinants of health.

I describe the framework rationale and elements and provide research and practice examples of its use in the US context. The approach may also apply to other health problems and in countries where similar inequities are observed.

Forty percent of US adults and nearly 20% of US youths aged 2 to 19 years have obesity, with increasing trends in adults and stable prevalence in youths.1 Obesity is epidemic globally, which is untenable because obesity has high health, social, economic, and personal costs.2 The causal narrative has become familiar: (1) population-wide obesity is linked to eating and physical activity patterns that are abnormal physiologically, yet have become normative; and (2) communities are laden with obesity-promoting influences, which overwhelm individuals’ efforts to control weight in a healthy range—a plethora of heavily marketed high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods and beverages combined with daily routines lacking in opportunities to be physically active.2 Changing these conditions requires comprehensive policy, systems, and environmental (PSE) changes to shift the range and balance of behavioral options toward an obesity-protective direction—no small feat and a long-term proposition.2–4

Patterns of obesity prevalence include marked disparities by race/ethnicity. For example, prevalence is significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black (55%) and Hispanic (51%) than non-Hispanic White women (38%), and in Hispanic (43%; but not non-Hispanic Black [37%]), than non-Hispanic White (38%) men.1 Prevalence in 2- to 19-year-old youths is significantly higher in non-Hispanic Black (22%) and Hispanic (26%) than non-Hispanic White (14%) youths.1 Socioeconomic status effects are complex and differ by race/ethnicity; lowest risk is not always observed in the highest socioeconomic status strata of income or education.5

These disparities are neither surprising nor coincidental. Risks of having obesity and related health problems are conditioned by adverse social circumstances, part of a deeper problem of systemic structural dynamics that curtail opportunities for advancement.6 Social disadvantage means a greater likelihood of living in poor-quality housing and in neighborhoods with fewer services and limited options for healthy eating and physical activity.7 Thus, even when progress is observed (e.g., declines in child obesity prevalence in some states and localities), detailed data may reveal widening gaps attributable to greater progress in White and higher-income than in ethnic minority and low-income youths.8,9

Assuming that any observed progress can be attributed to PSE initiatives implemented over the past 10 to 15 years, persistent or widening disparities suggest a lack of reach to or effectiveness with those who need them the most. Differences in uptake or benefit from PSE approaches were suggested by findings from a large observational study of childhood obesity prevention policies and programs in 130 US communities.10 Positive associations were reported for the comprehensiveness and intensity of these policies and programs with children’s weight status and diet or physical activity behaviors in White, high-income children and communities but not in children from low-income families or Black or Hispanic children.

Ensuring that populations affected disproportionately by obesity benefit from preventive strategies is among the most pressing unmet challenges in policy and practice. Marked racial/ethnic and income disparities were clearly evident in the 1980s, predating recognition of epidemic obesity in the US population at large.11 However, documenting disparities does not necessarily trigger deliberate or effective action to address them.

I propose an equity-oriented obesity prevention framework to guide practitioners and researchers in public health and other fields that contribute to obesity prevention in identifying ways to give greater priority to equity issues when undertaking PSE strategies. The framework is grounded in established public health and health equity principles. I explain the rationale and key conceptual elements and refer to practice and research examples.

RATIONALE

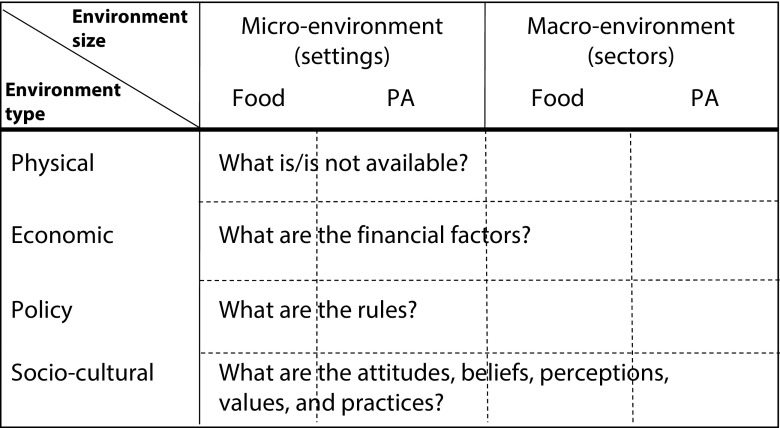

Many US obesity prevention strategies are informed by the analysis grid for environments linked to obesity (ANGELO) model of Swinburn et al. (Figure 1).4,12 This model dissects obesity-promoting environments (intervention settings) on the basis of level (macro or micro) and type of food or physical activity influences. ANGELO points to the potential for PSE approaches to change determinants of what foods are provided or available for purchase or consumption in schools, workplaces, supermarkets, retail outlets, restaurants, and public places and to related economic, policy, and sociocultural influences. ANGELO also points to determinants of options or requirements for being physically active for transportation or work or in educational settings, neighborhoods, parks, and recreational facilities. Sociocultural variables (e.g., attitudes, perceptions, norms) may not be immediately amenable to changes in built environments or policies but are critical for understanding the full picture.

FIGURE 1—

Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity (ANGELO)

Source. Adapted from Swinburn et al.12

Note. PA = Physical activity.

The ANGELO perspective is reflected in the 2005 Institute of Medicine national obesity action plan3 and their 2012 report on Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention (APOP).4 The APOP report used 5 environments or settings to organize recommendations that are culled from a large pool as the most promising strategies (see the box on page 1352), with an overarching recommendation for systems thinking to identify mutually reinforcing interventions. The APOP committee recognized that counseling programs or social-marketing campaigns could not curb the obesity epidemic in the absence of changes in environmental contexts for eating and physical activity and, therefore, gave the most emphasis to PSE approaches. Also, PSE approaches were supported by theory and evidence that changing environmental cues could enable healthier behaviors on the basis of people’s habitual or reflexive responses and by successes of public policy solutions in tobacco control and other areas of public health.3,4

Expert Committee Recommendations for Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: 2012.

| Recommendation | Strategies |

| Physical activity environments: Communities, transportation officials, community planners, health professionals, and governments should make promoting physical activity a priority by substantially increasing access to places and opportunities for such activity. | Enhance the physical and built environments. |

| Provide and support community programs designed to increase physical activity. | |

| Adopt physical activity requirement for licensed childcare providers. | |

| Provide support for the science and practice of physical activity. | |

| Food and beverage environments: Governments and decision-makers in the business community and private sector should make a concerted effort to reduce unhealthy food and beverage options and substantially increase healthy food and beverage options at affordable, competitive prices. | Adopt policies and implement practices to reduce overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages. |

| Increase the availability of lower-calorie and healthier food and beverage options for children in restaurants. | |

| Use strong nutritional standards for all foods and beverages sold or provided through the government and ensure that these healthy options are available in all places frequented by the public. | |

| Introduce, modify, and use health-promoting food and beverage retailing and distribution policies. | |

| Broaden the examination and development of US agriculture policy and research to include implications for the US diet. | |

| Information environments: Industry, educators, and governments should act quickly, aggressively, and in a sustained manner on many levels to transform the environment that surrounds people in the United States with messages about physical activity, food, and nutrition. | Develop and support a sustained, targeted physical activity and nutrition social-marketing program. |

| Implement common standards for marketing foods and beverages to children and adolescents. | |

| Ensure consistent nutrition labeling for the front of packages, retail store shelves, menus, and menu boards that encourages healthier food choices. | |

| Adopt consistent nutrition education policies for federal programs with nutrition education components. | |

| Health care and workplace environments: Health care and health service providers, employers, and insurers should increase the support structure for achieving better population health and obesity prevention. | Provide standardized care and advocate healthy community environments. |

| Ensure coverage of, access to, and incentives for routine obesity prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment. | |

| Encourage active living and healthy eating at work. | |

| Encourage healthy weight gain during pregnancy and breastfeeding and promote breastfeeding-friendly environments. | |

| Schools as a focal point for obesity prevention: Federal, state, and local government and education authorities, with support from parents, teachers, and the business community and the private sector, should make schools a focal point for obesity prevention. | Require quality physical education and opportunities for physical activity in schools. |

| Ensure strong nutritional standards for all food and beverages sold or provided through schools. | |

| Ensure food literacy, including skill development, in schools. |

Source. Institute of Medicine.4

A statement on the APOP logic model notes that the starting point for obesity prevention differs according to social contexts:

Race/ethnicity; gender; socioeconomic status; residential area; and social, political, and historical contexts . . . influence the baseline, opportunities, and responses to changes in environments for physical activity and eating.4(p20)

Suggested actions for nutrition-related strategies include increasing access to affordable, healthy foods in low-income or underserved communities and providing advice about healthy foods in nutrition assistance programs. However, only the breastfeeding recommendation explicitly highlighted the importance of addressing disparities. The limited attention to equity issues may have resulted from a lack of evidence about program effectiveness in ethnic minority and low-income populations.

This is a stark reminder that obesity prevention efforts have recognized but not adequately addressed disparities. Efforts directed to the general population may be assumed to also address disparities, but this has not been observed. At a subsequent 2013 Institute of Medicine obesity workshop on equity issues,13 speakers emphasized that disparities in contextual drivers of high risks of obesity reflect broader societal inequities and that attending to these broader inequities is important. Several provided examples of interventions designed to address context-specific challenges, but the workshop was not designed to recommend specific action pathways.

GETTING TO EQUITY IN OBESITY PREVENTION

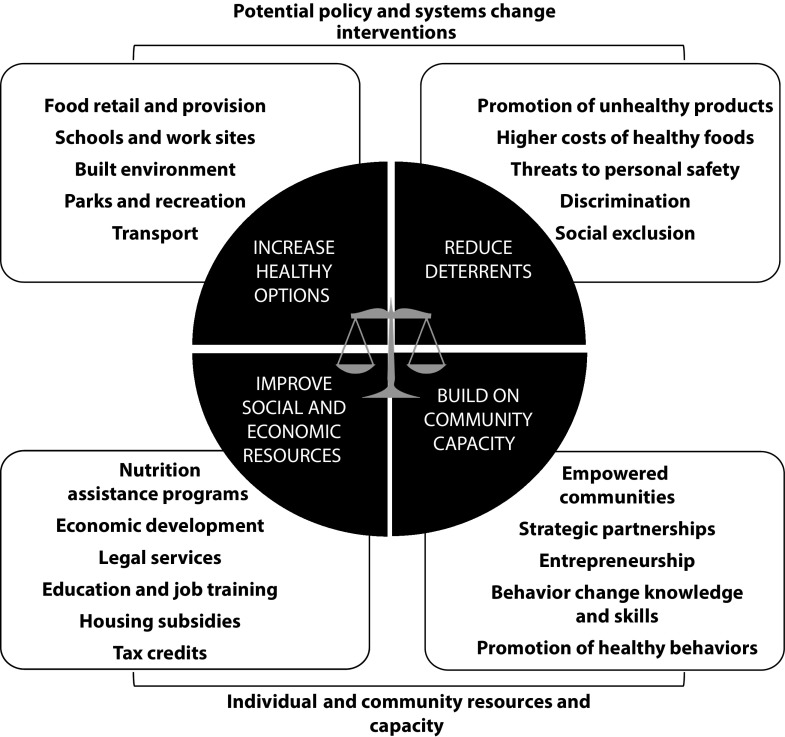

Figure 2 illustrates the getting to equity (GTE) framework that I developed for thinking through obesity-related PSE strategies with an intentional focus on equity.14 It takes advantage of emerging understandings and approaches in the broader field of health equity practice and research to translate the intention to achieve equity into a specific way of thinking and acting. It picks up from where we are now in the obesity prevention field; we recognize the importance of health equity but do not yet have a clear sense of how this can be achieved.

FIGURE 2—

Equity-Oriented Obesity Prevention Framework

Source. Adapted from Kumanyika.14

The figure has 4 quadrants, each with callouts to identify different types of intervention targets or approaches. The top quadrants show examples of recommended PSE interventions to improve healthy eating and active living (see the box on this page), referring to approaches with documented relevance to disparities. The bottom quadrants refer to individual and community resource and capacity issues viewed as critical considerations for the equity impact of obesity-related PSE strategies. The scales of justice in the center reflect the concept of synergy. As discussed in the APOP report, identifying potential synergies among obesity-related interventions involves considering relationships beyond the primary pathway for the effect: prerequisites needed before a specific intervention can be effective, accelerants that shorten the timeline for effectiveness or increase effective dose, and inhibitors that may slow down effectiveness or impede implementation.4 The GTE framework builds on this approach by prompting consideration of such additional pathways in the context of health equity. The premise is that disparities related to obesity and other health problems cannot be remedied without attention to underlying inequities.

Increasing healthy options refers to approaches that, if appropriately designed and implemented, can improve access to options for healthy eating and physical activity in socially disadvantaged communities7,15: improving locations and marketing practices of supermarkets; establishing standards for food provision in schools, worksites, and public places; and improving access to safe and appealing parks and recreational facilities, neighborhood walkability, and transit systems.

Reducing deterrents identifies opportunities to improve the balance of health-promoting and health-damaging exposures. High-calorie, nutrition-poor foods and beverages are marketed disproportionately to Black and Hispanic/Latino communities.16,17 Decreasing targeted marketing of unhealthy foods and beverages to children will, therefore, benefit children in these populations disproportionately. Sugary beverage taxes or limitations on where such beverages are available discourage their consumption and increase the relative affordability and availability of healthier options. Removing blight and decreasing crime are important for improving personal safety. Policies and programs that discourage or prohibit discrimination or exclusion of people in racial/ethnic minority and low-income populations can increase or facilitate access to and uptake of healthier options.

Improving social and economic resources involves identifying and using government and charitable programs that address hunger and food insecurity as well as social and economic programs such as those designed to alleviate poverty and address disparities in education, employment, housing, and legal protections. Those for whom the requisite social and economic resources and food security can be taken for granted may question the need for obesity-related programs to address these issues. However, resource issues are arguably the biggest difference between people in communities affected by disparities and people in other communities and cannot be ignored. Relevant interventions include individually oriented (e.g., direct services and referrals) and community- or policy-focused approaches (e.g., outreach, advocacy, policy change). Short-term approaches employ existing policies and programs to mitigate adverse social determinants of health. Long-term approaches must directly address these determinants.

Building on Community Capacity

PSE strategies affect fundamental aspects of food and physical activity environments and behaviors. Effectiveness and sustainability depend on community capacity to embrace, adapt, or create changes that fit their contexts. Community engagement to assess and build on existing capacity is critical. Capacity building is broadly relevant to public health and health equity and has many definitions and dimensions.18 Figure 2 highlights being empowered as a core element of capacity (i.e., having a voice in decision-making and the intention and ability to take action for positive change). Engaging in strategic partnerships is another critical element of community capacity.18 Such partnerships might span sectors such as housing, education, transportation, and economic development. Entrepreneurship education, technical assistance, and financing for business development, which help communities and community members generate and control revenue streams, have been used to address obesity and other health behaviors in US communities.19,20 However, in the United States, such approaches are underused and may be underappreciated as options for enhancing capacity. Also relevant to capacity is the fact that individually oriented behavior change and health promotion strategies work together with PSE strategies at the personal level, and they mobilize and sustain demand for PSE changes.

Synergy

Consistent with APOP recommendations for multifactorial approaches and a systems perspective,4 this aspect suggests that interventions will be mutually reinforcing in their effects on equity when approaches in and across the top and bottom levels are combined strategically. The synergies among PSE strategies (i.e., across the top 2 quadrants) are straightforward. For example, improving access to healthy beverage choices goes hand in hand with discouraging consumption of sugary beverages; improving access to parks and recreational facilities works best when steps are taken to ensure the safety of these facilities. Complementary strategies from the bottom half of the framework relate to synergies between individually oriented interventions and structural approaches that involve other sectors and mitigate or directly address social disadvantages. Direct attention to social determinants is recommended in the broader sphere of chronic disease prevention and control.21

APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK

Operationally, the process of using the framework involves seeking answers to certain questions about proposed PSE interventions, the characteristics and circumstances of the people expected to benefit from the interventions, and how interventions can be combined to foster synergy. Concepts implicit in this process are as follows.

Applying a Health Equity Lens

The intent to address health inequities calls for an equity lens—a set of field glasses that allows one to see both overt and subtle injustices at work and to reject biases and stereotypes that blame people for circumstances that are beyond their control. Having an equity lens can be described as

understanding the social, political, and environmental contexts of a program, policy, or practice to evaluate and assess the unfair benefits and burdens in a society or population.22(p24)

For example, people in ethnic minority or low-income populations are more likely to be excluded from opportunities that apply only to homeowners or require a college education and less likely to have jobs that provide health insurance and family leave.23,24 An equity lens also involves the following: familiarity with general equity principles and how to talk about them (common language), knowledge about historical contexts for inequities and how they were and continue to be shaped by privilege for some and oppression of others, understanding policymaking and implementation, and a commitment to ongoing learning and unlearning.22

The need for a health equity lens speaks to core societal and public health values and principles. The willingness and ability to adopt such a lens, and the effort involved, are shaped by a person’s social position, life experiences, biases, moral compass, and knowledge about inequities and how they arise as well as by the latent inequities that are institutionalized in health research and practice. In my view developing and maintaining such a lens is the most challenging but liberating aspect of using the GTE framework. Developing such a mental lens and articulating equity concerns are tedious and uncomfortable. The process unavoidably raises tensions about potentially contentious and divisive topics such as race/ethnicity, poverty, social class, and social justice. However, having an equity lens can free one up to think in new ways and see new possibilities for changing the course of a public health effort.

Identifying Design and Implementation Issues

“Universal” approaches are intended to reach entire populations or communities without selection on the basis of risk. PSE approaches do this by focusing on societal structures to “make the right choice the easy choice.” However, structural approaches do not obviate the need to attend to circumstances of people living in or experiencing the environments targeted by PSE interventions. Altering social structures in ways that make it easier for people to adopt healthy behaviors is a valid principle, “all other things being equal,” and it may seem efficient, cost effective and fair. However, when inequities exist, universal strategies should be adjusted proportionate to need (“proportionate universalism”).25 Proportionate universalism calls for having the same ultimate goals for everyone but using appropriately tailored strategies to achieve these goals. This is why a health equity lens is needed. Treating people equally (the same) is not the same as treating people equitably (fairly), where fair treatment may require providing additional or different resources to achieve the intended effect. A Scottish study demonstrated that greater dollar investment in urban renewal in the most disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with more favorable physical and mental health effects compared with areas with lower investments.25

Possible questions to ask when thinking through how a PSE intervention may need adjustment during implementation, or why a previous PSE initiative did not work from an equity perspective are the following: In what ways is the intervention relevant to this population and context? What is the primary pathway for the intervention effect and what assumptions suggest that this is a valid pathway? Are these assumptions met in this context? If not, what needs to be changed or added? What contextual factors or other interventions might influence the effects of the intervention? How can resources and capacity be enhanced to improve intervention effectiveness? The first 2 questions help to deconstruct the elements of the intervention. The remaining questions relate to identifying potentially synergistic combinations of interventions.

Understanding People and Their Circumstances

Applying a health equity lens also fosters the essential “people perspective” and leads to questions about the people–place or person–intervention interactions; these are shaped by their circumstances, needs, and aspirations: Who are the people in this setting? How might they differ from their counterparts in communities where these interventions seem to be working? What are they trying to accomplish? What resources and assets available in other settings are or are not present here? What non–obesity-related benefits might this intervention offer? What liabilities might it pose? No matter how well a PSE intervention is designed and implemented from a technical perspective, people’s experience of and responses to the intervention will ultimately determine its effectiveness on health. This is true generally but is critical to the GTE framework to ensure that departures from the usual assumptions are identified. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) REACH US (Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health across the United States) model provides relevant examples of successes in reducing obesity prevalence in Black communities.26

Obtaining valid answers to these questions about how to adjust intervention approaches and facilitate a good response requires community engagement. The importance of community engagement increases when the people designing and implementing the PSE interventions have limited knowledge of or experience with the relevant contexts or lives of those expected to benefit. Or practitioners and researchers may recognize constraints or capacity issues but be uncertain about how to overcome them. Community engagement is also important for understanding the capacity to support and sustain the PSE strategies apart from or after the external assistance has been withdrawn. Thus, ideally, equity-focused community engagement approaches will need to go beyond superficial or infrequent consultations.27,28

Combining Interventions

The framework emphasizes synergistic combinations of interventions. The process of identifying such combinations requires consideration of potential prerequisites, accelerants, or inhibitors available or needed in the full context and ways to partner accordingly so that complementary resources and expertise can be linked and used. Interventions to improve social and economic resources and to build on community capacity can be accessed through partnerships with agencies, practitioners, and researchers in other fields and sectors with expertise in these areas to enable direct action on social determinants of health, with potential cobenefits across sectors.

The top to bottom combinations will require environmental scans and crosstalk among sectors to increase mutual awareness of programs that could work together or strategies that can be mutually reinforcing. Another approach involves using measures that capture health effects of a social or economic intervention that is not designed to directly address health (e.g., an approach from the bottom left quadrant of the framework). The aforementioned Scottish study of investments in urban renewal25 is an example of this approach retrospectively. The US Moving to Opportunity social experiment on housing, which included assessments of several physical and mental health variables prospectively and identified favorable effects on obesity, is another.29

Case Examples

Improving effectiveness of new supermarkets.

The APOP report recommended strategies to attract supermarkets and other retailers selling healthy foods to underserved neighborhoods. The experience with this strategy is useful for illustrating how the GTE framework can guide analysis of a PSE approach from an equity perspective. Efforts to improve supermarket access have been implemented widely.30 However, although these efforts are found to benefit communities in certain ways, favorable effects on the healthfulness of community residents’ diets have been difficult to establish.30,31 Supplemental File A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) excerpted from the CDC “Practitioner’s Guide to Advancing Health Equity”32 provides a detailed example highlighting and suggesting potential ways to address equity issues related to this approach, consistent with the GTE framework.

In concept, such efforts to attract new businesses to underserved communities are rooted in well-established theory and practice from the field of community development.30 They typically consider factors such as physical location, store size and type, crime prevention, transportation routes, and potential economic impacts on the community. However, the desired effect of supermarket access on dietary quality may falter on the underlying assumptions about supermarket business models. Profits may be driven primarily by sales of foods that are high in sugar, fat, and salt even when the project has public health goals. A report that supermarkets and other grocery stores increase promotions of sugary beverages around the time that Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits are distributed underscores this point,33 as does another report indicating that people buy most of their healthy and unhealthy foods in supermarkets.34 The GTE framework would prompt for additional questions geared specifically to understanding how a new store might influence purchases of healthier versus less healthy foods in a low-income or ethnic minority community and what would be needed to enhance the potential for positive effects on dietary quality.

Impact of combined interventions.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was included in a study conducted by the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR) that was undertaken to identify policies and programs relevant to childhood obesity declines.35,36 This case study illustrates a comprehensive approach that included interventions from all 4 quadrants of the GTE framework as probable contributors to the relatively larger (although still modest) declines in obesity among children in some high-risk populations. The box on page 1356 shows my classification of the strategies employed in Philadelphia according to the GTE framework.37 Two strategies increased social and economic resources: participation of the Philadelphia School District in a pilot that allowed universal provision of school meals to all children in eligible schools and the Philly Food Bucks initiative, which provided participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program with financial incentives for fresh fruit and vegetable purchases. Because the NCCOR study focused on initiatives related to nutrition and physical activity, other types of initiatives (e.g., related to employment or housing) that might have contributed indirectly by improving social and economic resources were not assessed. The GTE framework encourages assessment of a broader scope of upstream variables.

Classification of Policies and Programs Noted as Possible Contributors to Childhood Obesity Declines Among Children in Grades K–8: Philadelphia, PA, 2003–2012.

| Increase options for healthy eating or physical activity |

|

| Decrease deterrents to healthy eating or physical activity |

|

| Increase resources |

|

| Build community capacity |

|

ADDITIONAL GUIDANCE

Several resources that demonstrate the type of thinking and action needed to apply the GTE framework in practice are available, including some that address obesity-related PSE strategies. The CDC guide I referenced includes step-by-step analyses of equity issues in PSE interventions related to healthy eating, active living, and tobacco control.32 Each example makes the case for relevant health equity considerations, identifies potential barriers and unintended consequences and tools for addressing them, and advises on building successful partnerships. CDC’s REACH US model is relevant as well.26 The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Finding Answers initiative includes a roadmap with best practices for addressing disparities in health care settings.38

In addition, motivated by the GTE framework, a tool to facilitate assessment of the potential equity impact of proposed intervention research was developed for a major funder of obesity- and nutrition-related PSE research (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Healthy Eating Research program). It consists of a series of questions about whether and how well the specific aims, rationale, and approach consider equity issues. Supplemental File B (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides a version of this tool with an appended explanation of its rationale and key concepts. The tool is grounded on principles generally applicable to evaluating research proposals and, therefore, is not specific to nutrition or obesity. The tool can be applied to both targeted studies (those that focus exclusively on a high-risk population) and studies that include both lower- and higher-risk populations.

CONCLUSIONS

I argue that meeting the challenges of achieving equity in contexts for healthy eating, active living, and obesity prevention requires that those engaged in this arena adopt an explicit “equity” lens using principles of social justice, acknowledging the realities of social inequities, and designing and evaluating interventions accordingly. Strategies to ameliorate or eliminate social disadvantages must be critical considerations for any solutions applied. The GTE framework is consistent with the movement to prioritize multisectoral, comprehensive, systems-oriented approaches to advance population health and health equity.39 This not only benefits those who are socially marginalized but is also foundational to overall population health and well-being. Finally, although the focus here is on obesity in the United States, the approach may apply to other health problems and in countries where similar inequities are observed.40

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This essay was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Healthy Eating Program.

The author first published the getting to equity framework as an online discussion article for the Roundtable on Obesity Solutions, Health and Medicine Division, National Academy of Medicine in the National Academies Perspectives Series. This AJPH article includes a slightly modified version of the framework and a comprehensive consideration of its rationale, elements, and potential uses.

Gratitude is expressed for thoughtful critiques provided by Mary Story and Megan Lott at the Healthy Eating Research Program and to the AJPH peer reviewers.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Protection of human participants is not needed because no data from human participants were involved.

Footnotes

See also Wang, p. 1321.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(288):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–814. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of obesity among adults, by household income and education—United States, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(50):1369–1373. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6650a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braveman P. A health disparities perspective on obesity research. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31(1):7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li W, Buszkiewicz JH, Leibowitz RB, Gapinski MA, Nasuti LJ, Land TG. Declining trends and widening disparities in overweight and obesity prevalence among Massachusetts public school districts, 2009–2014. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e76–e82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babey SH, Hastert TA, Wolstein J, Diamant AL. Income disparities in obesity trends among California adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2149–2155. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumanyika SK. Supplement overview: what the Healthy Communities Study is telling us about childhood obesity prevention in US communities. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13(suppl 1):3–6. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. Health, United States, 2014: With Special Feature on Adults Aged 55–64. Hyattsville, MD: US National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; US National Center for Health Statistics. Report no. 2015-1232. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med. 1999;29(6):563–570. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. Creating Equal Opportunities for a Healthy Weight: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumanyika S. Getting to Equity in Obesity Prevention: A New Framework. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larson NI, Story MT, Nelson MC. Neighborhood environments: disparities in access to healthy foods in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adeigbe RT, Baldwin S, Gallion K, Grier S, Ramirez AG. Food and beverage marketing to Latinos: a systematic literature review. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(5):569–582. doi: 10.1177/1090198114557122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grier SA, Kumanyika SK. The context for choice: health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1616–1629. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberato SC, Brimblecombe J, Ritchie J, Ferguson M, Coveney J. Measuring capacity building in communities: a review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):850. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benedict S, Campbell M, Doolen A, Rivera I, Negussie T, Turner-McGrievy G. Seeds of HOPE: a model for addressing social and economic determinants of health in a women’s obesity prevention project in two rural communities. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(8):1117–1124. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.CDC9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jennings L. Do men need empowering too? A systematic review of entrepreneurial education and microenterprise development on health disparities among inner-city Black male youth. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):836–850. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9898-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haire-Joshu D, Hill-Briggs F. The next generation of diabetes translation: a path to health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40:391–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine. Framing the Dialogue on Race and Ethnicity to Advance Health Equity. Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heymann J, Sprague AR, Nandi A et al. Paid parental leave and family wellbeing in the sustainable development era. Public Health Rev. 2017;38:21. doi: 10.1186/s40985-017-0067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassett MT, Graves JD. Uprooting institutionalized racism as public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(4):457–458. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egan M, Kearns A, Katikireddi SV, Curl A, Lawson K, Tannahill C. Proportionate universalism in practice? A quasi-experimental study (GoWell) of a UK neighbourhood renewal programme’s impact on health inequalities. Soc Sci Med. 1982;2016(152):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao Y, Siegel PZ, Garraza LG et al. Reduced prevalence of obesity in 14 disadvantaged Black communities in the United States: a successful 4-year place-based participatory intervention. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1442–1448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oetzel J, Scott N, Hudson M et al. Implementation framework for chronic disease intervention effectiveness in Maori and other indigenous communities. Global Health. 2017;13(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Subica AM, Grills CT, Douglas JA, Villanueva S. Communities of color creating healthy environments to combat childhood obesity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):79–86. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanbonmatsu L, Marvokov J, Porter N et al. The long-term effects of Moving to Opportunity on adult health and economic self-sufficiency. Cityscape. 2012;14(2):109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chrisinger BW. Taking stock of new supermarkets in food deserts: patterns in development, financing, and health promotion. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Community Development Investment Center Working Paper. 2016. Available at: http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/working-papers/2016/august/new-supermarkets-in-food-deserts-development-financing-health-promotion. Accessed July 12, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Dubowitz T, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Cohen DA et al. Diet and perceptions change with supermarket introduction in a food desert, but not because of supermarket use. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1858–1868. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A practitioner’s guide for advancing health equity: community strategies for preventing chronic disease. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/state-local-programs/health-equity-guide/index.htm. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 33.Moran AJ, Musicus A, Gorski Findling MT et al. Increases in sugary drink marketing during Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefit issuance in New York. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An R, Maurer G. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and discretionary foods among US adults by purchase location. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70(12):1396–1400. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jernigan J, Kettel Khan L, Dooyema C et al. Childhood Obesity Declines project: highlights of community strategies and policies. Child Obes. 2018;14(suppl 1):S32–S39. doi: 10.1089/chi.2018.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robbins JM, Mallya G, Wagner A, Buehler JW. Prevalence, disparities, and trends in obesity and severe obesity among students in the school district of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2006–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E134. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.150185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dawkins-Lyn N, Greenberg M. Signs of progress in childhood obesity declines. 2015. Available at: https://www.nccor.org/downloads/CODP_Site%20Summary%20Report_Philadelphia_public_clean1.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2019.

- 38.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(8):992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.From Vision to Action: A Framework and Measures to Mobilize a Culture of Health. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumanyika S, Taylor WC, Grier SA et al. Community energy balance: a framework for contextualizing cultural influences on high risk of obesity in ethnic minority populations. Prev Med. 2012;55(5):371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]