Abstract

Relay, a peer-delivered response to nonfatal opioid overdoses, provides overdose prevention education, naloxone, support, and linkage to care to opioid overdose survivors for 90 days after an overdose event. From June 2017 to December 2018, Relay operated in seven New York City emergency departments and enrolled 649 of the 876 eligible individuals seen (74%). Preliminary data show high engagement, primarily among individuals not touched by harm reduction or naloxone distribution networks. Relay is a novel and replicable response to the opioid epidemic.

In this article, we describe an innovative nonfatal overdose response system delivered by peers in selected emergency departments across New York City.

INTERVENTION

As part of a multipronged public health approach to address the opioid overdose epidemic, the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene recently implemented Relay, an emergency department (ED)–based overdose prevention intervention delivered by peer advocates. Although most individuals are transported to an ED after a nonfatal overdose, EDs infrequently have standardized protocols to address patients’ overdose risk or provide follow-up care.1 Thus, EDs are ideal locations to implement a standardized overdose risk reduction intervention.

Trained peer advocates are deployed to collaborating EDs immediately after a reported overdose. With firsthand experience with substance use, peer advocates offer nonjudgmental, noncoercive services and resources while serving as positive role models, establishing rapport, and fostering engagement among overdose survivors.

Relay has two main components, the initial ED interaction and then a 90-day period of continued peer navigation and support. Relay’s key elements include an assessment of patients’ drug use and risk history, overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution, support, and identification of need for and subsequent linkage to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, harm reduction, and other support services (e.g., medical care, housing, case management). Overdose prevention education includes five key messages to reduce overdose risk: avoid drug use alone, take turns using, inject or snort slowly, avoid mixing substances, and have naloxone available. Individually, Relay’s key elements—peer-delivered support, overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution,2 multiple contacts rather than a single contact,3 and referrals to medication for addiction treatment4—increase engagement in care and reduce overdose and all-cause mortality.

PLACE AND TIME

Relay is currently active in seven EDs across six hospital systems in the NYC neighborhoods with the highest rates of overdose. Relay launched in a rolling fashion from June 2017 through October 2018. The program will expand to 15 hospital systems by 2020.

PERSON

Relay targets individuals who have just experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose, because their risk of death is twice that of people who use drugs but have not experienced an overdose.5 Patients are eligible for Relay if they have experienced an opioid-related overdose, are 18 years or older, are not incarcerated or in police custody in the ED, and are not mentally or cognitively incapable of providing consent to participate.

PURPOSE

Relay’s long-term goal is to reduce overdose events, including unintentional overdose deaths, in NYC; there were 1478 overdose deaths in NYC in 2017, more than 80% of which involved an opioid.6 Short-term goals are to engage Relay participants, provide overdose prevention education and naloxone kits to participants and their social networks, and offer linkage to services. Relay is modeled on similar programs implemented in other jurisdictions7 but includes an extended 90-day follow-up period and a harm reduction approach.

IMPLEMENTATION

The Department of Health and Mental Hygiene collaborates with partner EDs to integrate Relay into existing workflows in an effort to ensure that the intervention is activated for all suspected nonfatal opioid overdose patients without burdening staff. ED staff activate Relay by calling a toll-free number available 24 hours per day, seven days per week. Relay assigns two full-time (Monday–Friday, 7 am to 7 pm) and four part-time (evenings, overnights, and weekends) peer advocates to each ED. They arrive at EDs within one hour of notification, at which time providers ask patients whether they are willing to speak with a peer advocate.

After the initial ED engagement, peer advocates explain that follow-up is available for 90 days. Peer advocates target contacts at 24 to 48 hours after discharge; 30, 60, and 90 days after discharge; and intermittently as requested. Both mode (in person, telephone, or text) and content of interactions vary by participant and time; in-person contact is the primary goal. At each interaction, peer advocates address participants’ needs, reinforce overdose prevention messages, provide naloxone kits, schedule appointments, and escort participants to services. Participants who are contemplating services but not ready to schedule appointments receive detailed information on the provider or organization to which they were referred (e.g., name, hours, contact information).

Relay participants are commonly referred to SUD treatment (medication for addiction treatment, other outpatient or inpatient SUD treatment), medical care (e.g., HIV and hepatitis screening and treatment, primary care, mental health care), housing assistance programs, benefits counseling, and harm reduction programs. As a means of reaching social networks of people at risk for overdose, overdose education and naloxone kits are offered to both participants and individuals who decline to participate, as well as friends or family members (with patient consent). Information is entered into a database that serves as both a case management and data collection tool.

EVALUATION

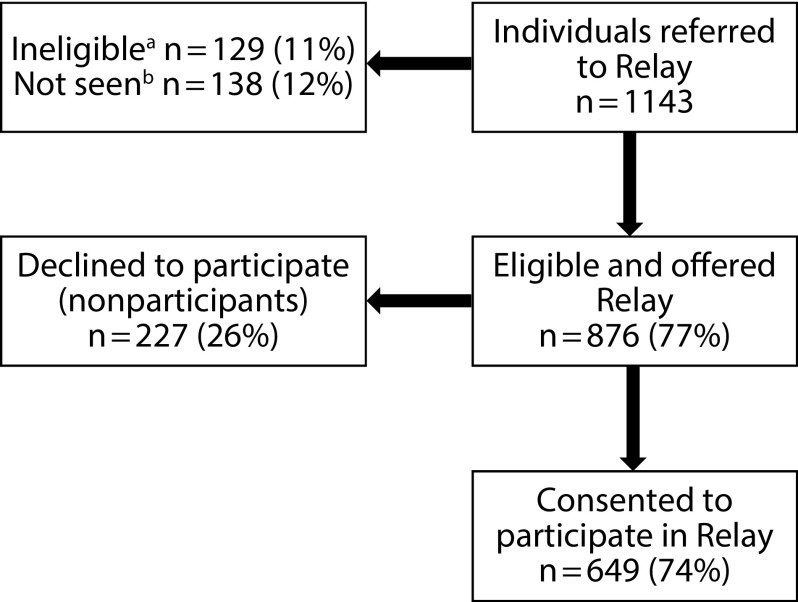

Between June 1, 2017, and December 31, 2018, 1143 individuals were referred to Relay, of whom 876 were eligible for participation. Of these 876 individuals, 649 (74%) agreed to participate in Relay (Figure 1). Almost one half (47%) of participants were reached for follow-up 24 to 48 hours after discharge. Contact rates at the 30-, 60-, and 90-day check-ins were 36%, 36%, and 33%, respectively.

FIGURE 1—

Relay Eligibility and Participation: New York City, June 1, 2017–December 31, 2018

aPatients were considered ineligible for Relay if (1) the event was not an opioid-related overdose, (2) they were in police custody or under arrest in the emergency department, (3) they were currently incarcerated, or (4) they were mentally or cognitively incapable of providing consent to participate.

bPatients who were unable to be seen by Relay staff (e.g., those who were in a coma or not medically stabilized, those who left the hospital before staff arrived, and those who were too agitated or distressed to be seen by staff).

Nearly three quarters (72%) of participants were male, nearly half (48%) were Latino/a, and 42% were 35 to 54 years of age. More than one third (37%) had previously experienced at least one other overdose (Table 1). Antecedent to their current overdose, the majority had used heroin (70%); 23% reported injecting drugs, the same percentage were taking medication for addiction treatment, 17% were enrolled in another type of SUD treatment, and only 8% were receiving services from a harm reduction program (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Demographic Characteristics; Overdose, Substance Use, and Treatment History; and Program Referrals: Relay Participants in New York City, June 1, 2017, to December 31, 2018

| No. (%) or Median (IQR) | |

| Total | 649 (100) |

| Male | 464 (72) |

| Race/ethnicitya | |

| White | 192 (30) |

| Black/African American | 118 (18) |

| Latino/a | 306 (48) |

| Middle Eastern | 7 (1) |

| Asian | 6 (1) |

| Otherb | 10 (2) |

| Age, ya | |

| 18–34 | 190 (30) |

| 35–54 | 265 (42) |

| ≥55 | 180 (28) |

| Homelessa (living in shelter or on the street) | |

| Yes | 173 (29) |

| No | 415 (71) |

| Previous overdose | |

| Yes | 242 (37) |

| No | 319 (49) |

| Unknown | 88 (14) |

| Median number of overdosesc | 2 (2) |

| Opioids involved in current overdose eventd | |

| Heroin | 457 (70) |

| Opioid analgesics | 90 (14) |

| Methadone | 45 (7) |

| Other drugs involved in current overdose eventd | |

| Cocaine | 81 (12) |

| Benzodiazepines | 89 (14) |

| Alcohol | 76 (12) |

| Reported injection of any drugs involved in current overdose event | 147 (23) |

| First-time receipt of a naloxone kita | 370 (60) |

| Treatment/service use history | |

| Currently engaged with a harm reduction program | 46 (8) |

| Received other drug treatment in past 12 moe | 101 (17) |

| Medication for addiction treatmentf | 142 (23) |

| Referralsg | 312 (48) |

| Harm reduction program | 165 (25) |

| Medication for addiction treatmentf | 104 (16) |

| Other outpatient substance use disorder treatment | 72 (11) |

| Inpatient substance use disorder treatment | 66 (10) |

| Referrals keptg,h | |

| Harm reduction program | 19 (53) |

| Medication for addiction treatmentf | 48 (79) |

| Other outpatient substance use disorder treatment | 27 (73) |

| Inpatient substance use disorder treatment | 41 (79) |

Note. IQR = interquartile range.

Fourteen participants were missing data on age, 10 on race/ethnicity, 61 on housing, and 31 on first-time receipt of a naloxone kit.

Other includes American Indian, Native Hawaiian, and multiracial.

Among participants reporting number of previous overdoses (n = 228).

Based on self-report; not mutually exclusive.

Inpatient or outpatient detoxification or rehabilitation and counseling.

Methadone or buprenorphine (or both).

Received at least one referral to one of the listed service types; referrals provided through March 31, 2019. Referrals are not mutually exclusive; participants may have received a referral to more than one service type.

Among patients with known referral status, as some participants were not able to be reached for follow-up: harm reduction, n = 36; medication for addiction treatment, n = 61; outpatient substance use disorder treatment, n = 37; and inpatient substance use disorder treatment, n = 52.

Relay peer advocates distributed 1007 naloxone kits to 827 unique participants, nonparticipants, and their social networks. Of the 649 Relay participants, 370 had not previously received a naloxone kit, 165 accepted referrals to harm reduction services, 104 accepted referrals to medication for addiction treatment, 72 accepted referrals for outpatient SUD treatment, and 66 accepted referrals for inpatient SUD treatment. Among those with known referral status, the percentage of kept appointments ranged from 53% to 79% (Table 1).

ADVERSE EFFECTS

As of March 31, 2019, in this group at high risk of overdose, there were 71 subsequent nonfatal overdoses and four fatal overdoses (reported by family members). To our knowledge, there were no other adverse events among participants, providers, or Relay staff as a result of the intervention.

SUSTAINABILITY

Relay is funded and operated by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; however, a Relay-type intervention could be sustainable if insurers were to reimburse for peer advocate services. In some states, including New York, peer-delivered interventions are reimbursable via Medicaid, and thus peers employed by community-based organizations could deliver the intervention. Future studies should examine the cost effectiveness of and savings associated with the model.

PUBLIC HEALTH SIGNIFICANCE

Relay delivers an evidence-based intervention to individuals at high risk for future drug overdose in neighborhoods with the highest rates of overdose, establishing a standardized nonfatal overdose response in a setting that lacked existing mechanisms to provide overdose prevention education, naloxone, and follow-up services. A large proportion of patients seen in EDs were successfully engaged in Relay. We recognize that the proportion of participants receiving and ultimately keeping referrals to treatment and services was low, which is not surprising in this non-help-seeking cohort. The number of subsequent fatal and nonfatal overdose events also is not unexpected in this high-risk population; the impact of targeted information, naloxone, and peer support that could improve long-term outcomes needs further study.

To assess Relay’s long-term goal of reducing future overdose among participants, we plan to assess fatal and nonfatal overdoses, hospitalizations, and all-cause mortality rates among participants and compare the results with those from a nonintervention cohort. Preliminary data showing high engagement rates and participation among large proportions of individuals not previously touched by harm reduction or naloxone distribution networks provide promising evidence for an ED-based intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Relay peer advocates for their hard work and dedication, the Relay participants, and the Relay supervisors and evaluation and administrative staff for support and oversight of the program.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

REFERENCES

- 1.Houry DE, Haegerich TM, Vivolo-Kantor A. Opportunities for prevention and intervention of opioid overdose in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;71(6):688–690. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(9):645–654. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caudarella A, Dong H, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Wood E, Hayashi K. Non-fatal overdose as a risk factor for subsequent fatal overdose among people who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;162:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan ML, Tuazon E, Blachman-Forshay J, Paone D. Unintentional drug poisoning (overdose) deaths in New York City, 2000 to 2017. Available at: https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/databrief104.pdf. Accessed July 27, 2019.

- 7.Samuels E. Emergency department naloxone distribution: a Rhode Island Department of Health, recovery community, and emergency department partnership to reduce opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J. 2014;97(10):38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]