Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) is a vital enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides. Inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH hold great potential as new generation antimicrobial agents.

Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) is a vital enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides. Inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH hold great potential as new generation antimicrobial agents.

Abstract

Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) is a vital enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides. IMPDH catalyzes a crucial step of converting IMP into XMP that is further converted into GMP. Microbial infections rely on the rapid proliferation of bacteria, and this requires the rate-limiting enzyme IMPDH to expand the guanine nucleotide pool and hence, IMPDH has recently received lots of attention as a potential target for treating infections. Owing to the structural and kinetic differences in the host IMPDH and bacterial IMPDH, a selective targeting is possible and is a crucial feature in the development of new potent and selective inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH. Earlier screening of small molecules revealed a structural requirement for the bacterial/protozoal IMPDH. Early optimization of benzimidazole and benzoxazole scaffolds led to the discovery of new potent and selective inhibitors of pathogenic IMPDH. Further research is vastly focused on the development of highly potent and selective inhibitors of various bacterial IMPDHs. Such studies reveal the importance of this excellent target for treating infectious diseases. The current review focuses on the recent developments in the discovery and development of selective inhibitors of bacterial/protozoal IMPDH with emphasis on the inhibition mechanism and structure–activity relationship.

Introduction

Infectious diseases are still a leading cause of death worldwide. Treatment of infectious diseases includes a mono or combination therapy of antibiotics. Unfortunately, the emergence of drug resistance to classical and currently used antibiotics is a major problem faced in treating infections. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), antibiotic resistance is one of today's biggest threats to global health, food security, and development.1 Some of the mechanisms involved in the development of drug resistance in bacterial infections include mutations, chemical alterations or destruction of antibiotic molecules by enzymes produced by bacteria, decreased drug uptake due to decreased cell wall permeability, increased efflux of drug molecules due to expression of efflux pumps, change in the target site or overall cell adaptation to the therapy.2 Despite the availability of several antibiotics, their use has been rendered ineffective due to the emergence of drug resistance.

Increasing risk of drug-resistant strains of deadly pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Salmonella Typhi and Helicobacter pylori, needs special efforts to find therapies. Hence, there is an urgent need to identify a new target or strategy to tackle the challenge of drug resistance. One of such targets is inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH). In the past decade, IMPDH has received great attention as a viable target for treating various diseases and bacterial infections. Few reviews on the potential of IMPDH inhibitors (human IMPDH II and prokaryotic IMPDH) for their therapeutic applicability have appeared in the past.3–5 A recent work by Cuny et al. had a special emphasis on the human IMPDH inhibitors reported in patents.6 In the current review, we have made efforts to put forward the development of pathogenic IMPDH inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents to treat infectious diseases and current advances in this field.

Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) as a target

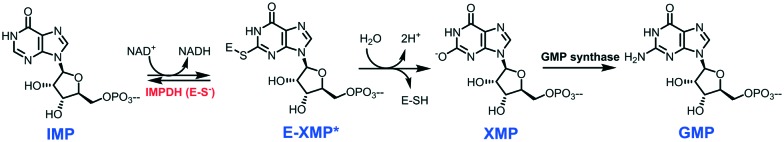

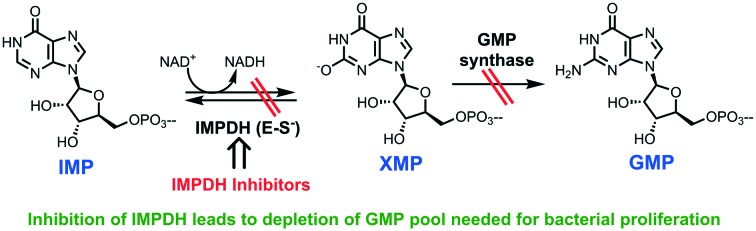

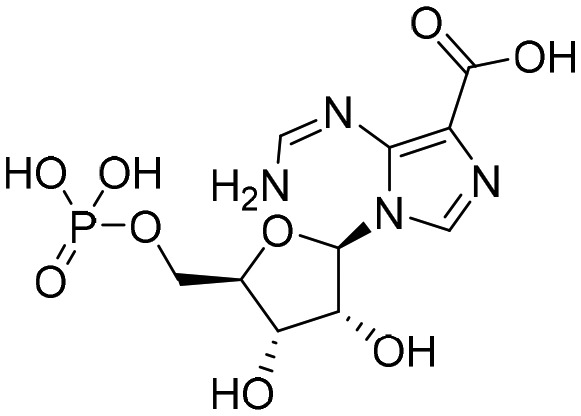

Inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH; EC 1.1.1.205) is a crucial enzyme in the synthesis of guanine ribonucleotides. It catalyzes the first step in the biosynthesis of guanine nucleotides, inosine-5′-monophosphate (IMP) is converted into xanthosine-5′-monophosphate (XMP) with concurrent reduction of NAD+.7,8 XMP is further converted into guanosine 5′-monophosphate (GMP) by GMP synthase (Fig. 1), which successively by action of several enzymes on GMP gives rise to some of the building blocks of DNA (dGTP) and RNA (GTP).

Fig. 1. Role of IMPDH in the biosynthesis of GMP through the conversion of IMP to XMP. IMP: inosine-5′-monophosphate; XMP: xanthosine-5′-monophosphate; E-XMP: IMPDH–XMP complex; GMP: guanosine 5′-monophosphate.

For cell growth and proliferation, guanine nucleotides are needed, and hence inhibiting the IMPDH leads to a decrease in the proliferation.9 IMPDH has been extensively studied as a chemotherapeutic target. Different IMPDH inhibitors like mycophenolic acid,10 mizorubine,11 ribavirin,12 and tizafurin13 are also being used as a part of anticancer, antiviral and immunosuppressive therapies. One of the first reports of inhibition of bacterial IMPDH can be traced back to the work of Liz Hedstrom (1999) which described the mechanism of action and inhibition of IMP dehydrogenase.14 Additionally, in the same year, two inhibitors 6-chloro-IMP and selenium analog SAD (beta-methylene-selenazole-4-carboxy amide-adenine dinucleotide) binding in the IMP and NAD pockets of human IMPDH were identified and revealed the binding mode of the dinucleotide cofactor to the enzyme.15,16 Later, the work done by Sintchak MD at Vertex Pharmaceuticals highlighted the significance of the structural and mechanistic information of the IMPDH enzyme in the process of a structure-based drug design program for the design of IMPDH inhibitors. Their extensive research has led to the design and identification of VX-497 as an uncompetitive inhibitor of IMPDH and a potent immunosuppressive agent in vitro and in vivo. Currently, it is taken to phase-II trials for the treatment of patients with psoriasis and hepatitis C.

Structural features of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH)

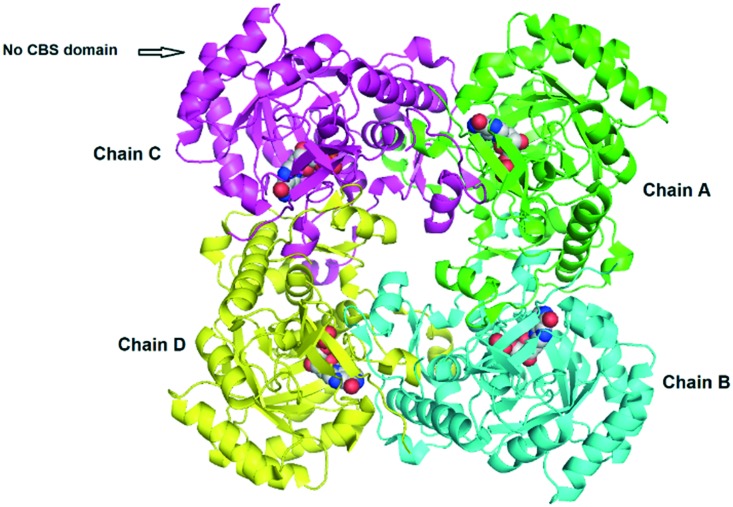

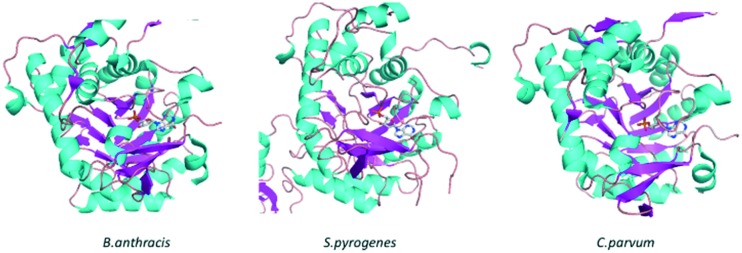

To date, there are 94 crystal structures of IMPDH reported in the protein data bank (PDB). Out of these, 65 are reported for bacterial IMPDH, 28 for eukaryotic IMPDH and 01 for archaea. Many of these crystal structures have been co-crystallised with inhibitors giving key information on binding modes. Table 1 lists the bacterial IMPDH co-crystallised with inhibitors.17–23 In most of these crystal structures IMPDH exists as a tetramer with a square planar geometry; each monomer has two domains, a catalytic domain, with the classic β8/α8 barrel and a subdomain containing two cystathionine beta-synthase domains (CBS domain or Bateman domain), and their exact function in IMPDH is currently under investigation. In addition, it is reported that the subdomains are not essential for the activity of IMPDH. Deletion of these subdomains by mutagenesis has no effect on the enzymatic activity; in addition, it facilitates the crystallization of IMPDH (Fig. 2).24,25 The catalytic loops of all the bacterial IMPDH are highly conserved and the active site is found in the loops on the C-terminal ends of the β sheets (Fig. 3).8,26 The Cys319 residue is also conserved in most of the IMPDH and present in the activation loops. This plays an important role in the enzymatic activity by attacking C2 of IMP covalently during the dehydrogenase reaction.8

Table 1. Inhibitors of IMPDH co-crystallised with different bacterial IMPDHs. The data are obtained from the RCSB protein data bank (PDB).

| Bacterium/pathogen | Ligand co-crystallised [IMPDH PDB ID] |

|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

TBK6 [; 5UPU]

TBK6 [; 5UPU] |

P41 [; 4ZQN]

P41 [; 4ZQN] |

G36 [; 5UPV]

G36 [; 5UPV] |

Q67 [; 4ZQO]

Q67 [; 4ZQO] |

|

MAD1 [; 4ZQP]

MAD1 [; 4ZQP] | ||

| Mycobacterium thermoresistibile |

Compound

1

(7759844) [; 5OU1]

Compound

1

(7759844) [; 5OU1] |

VCC234718 [; 5J5R]

VCC234718 [; 5J5R] |

Compound

2

(NMR744) [; 5OU2]

Compound

2

(NMR744) [; 5OU2] |

Compound 1/TBK6 [; 5K4X]

Compound 1/TBK6 [; 5K4X] |

|

Compound

31

(AT080) [; 5OU3]

Compound

31

(AT080) [; 5OU3] |

Compound

6 [; 5K4Z]

Compound

6 [; 5K4Z] |

|

| Campylobacter jejuni |

P225 [; 5UQF]

P225 [; 5UQF] |

Oxanosine monophosphate [; 6MGR]

Oxanosine monophosphate [; 6MGR] |

P200 [; 5UQG]

P200 [; 5UQG] |

C91 [; 4MZ8]

C91 [; 4MZ8] |

|

P182 [; 5UQH]

P182 [; 5UQH] |

P12 [; 4MZ1]

P12 [; 4MZ1] |

|

P176 [; 5URQ]

P176 [; 5URQ] | ||

| Bacillus anthracis |

Oxanosine monophosphate [; 6MGU]

Oxanosine monophosphate [; 6MGU] |

P200 [; 5UUZ]

P200 [; 5UUZ] |

P178 [; 5URS]

P178 [; 5URS] |

P176 [; 5URR]

P176 [; 5URR] |

|

P221 [; 5UUW]

P221 [; 5UUW] |

P182 [; 5UUV]

P182 [; 5UUV] |

|

| Bacillus anthracis str. Ames |

P32 [; 4MYX]

P32 [; 4MYX] |

P68 [; 4MY1]

P68 [; 4MY1] |

D67 [; 4QM1]

D67 [; 4QM1] |

A110 [; 4MYA]

A110 [; 4MYA] |

|

C91 [; 4MY9]

C91 [; 4MY9] |

Q21 [4MY8]

Q21 [4MY8] |

|

| Clostridium perfringens |

P225 [; 5VSV]

P225 [; 5VSV] |

P178 [; 5UXE]

P178 [; 5UXE] |

P221 [; 5UZC]

P221 [; 5UZC] |

P176 [; 5UWX]

P176 [; 5UWX] |

|

P182 [; 5UZE]

P182 [; 5UZE] |

C91 [; 4Q32]

C91 [; 4Q32] |

|

P200 [; 5UZS]

P200 [; 5UZS] |

A110 [; 4Q33]

A110 [; 4Q33] |

|

| Cryptosporidium parvum |

P131 [; 4RV8]

P131 [; 4RV8] |

N109 [; 4QJ1]

N109 [; 4QJ1] |

Q21 [; 4IXH]

Q21 [; 4IXH] | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

F2K [; 6GK9]

F2K [; 6GK9] |

|

| Listeria monocytogenes |

Q21 [; 5UPY]

Q21 [; 5UPY] |

|

| Vibrio cholerae |

Mycophenolic acid [; 4FXS]

Mycophenolic acid [; 4FXS] |

|

Fig. 2. IMPDH crystal structure of Bacillus anthracis (PDB ID: ; 5UUZ) with no CBS domain. Each chain is represented with a different color & IMP as shown in the space-filling model.

Fig. 3. Catalytic loops of B. anthracis, S. pyrogenes, and C. parvum. β-Sheets are colored in magenta, helices are colored in cyan and loops are colored in wheat: IMP is shown as a ball and stick model.

During the dehydrogenase reaction, IMPDHs attain an open conformation that allows NAD+ binding. These observations show that the conformational transition of IMPDH structures during the IMPDH reaction affords the expansion of a variety of antibiotics that can mimic the IMP or NAD+ binding for the generation of competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive and covalent inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH.

On the other hand, the lack of experimental structures of bacterial IMPDH has led to comparative modeling and in silico docking studies that help in rationalizing the structure–activity relationship of inhibitors against pathogenic bacterial IMPDH.27,28 Our recent in silico studies on H. pylori IMPDH have highlighted the identification and development of indole derivatives as non-competitive inhibitors for IMPDH.

IMPDH as a target for treating infections

A wide variety of pathogenic bacteria known to cause several human infections or diseases are given here (a partial list with diseases in parentheses): Helicobacter pylori (stomach infection), Cryptosporidium parvum (cryptosporidiosis), Streptococcus pyogenes (pharyngitis, cellulitis, neonatal infection), Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumonia), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhoea), Acinetobacter baumannii (wound infection), Bacillus anthracis (anthrax), Mycobacterium leprae (leprosy), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tuberculosis), Campylobacter jejuni (food poisoning) and Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease).29–37 Currently, there is no effective therapy for many of these pathogenic bacteria. On the other hand, some of these pathogens developed multi-drug resistance to the commonly used antibiotics, thus creating an urgent need for the identification and development of novel scaffolds and targets. Inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) is one such enzyme target that presents potential for the development of next-generation antibiotics.

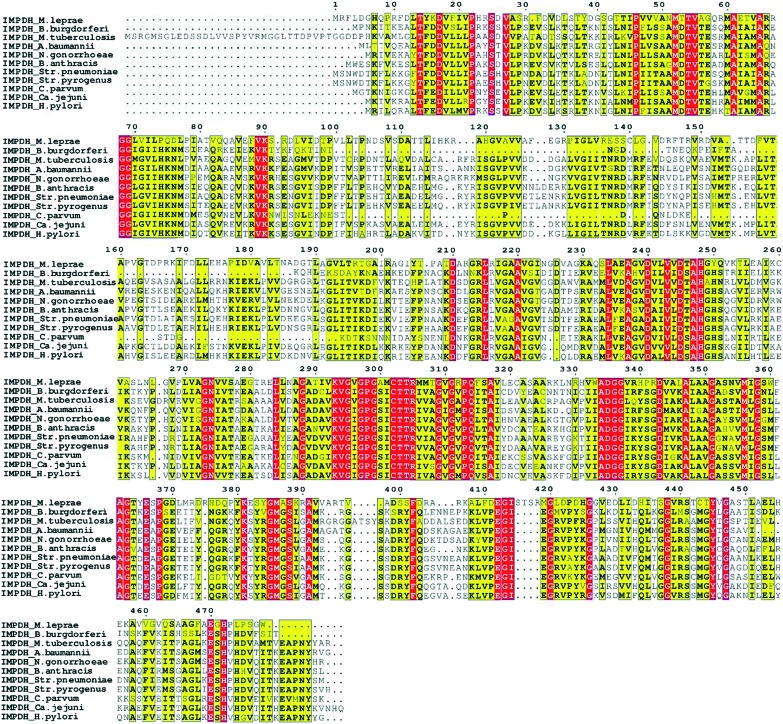

Microbial infections rely on the rapid proliferation of bacteria and this requires the rate-limiting enzyme IMPDH to expand the guanine nucleotide pool. As IMPDH is involved in the de novo biosynthesis pathway of these guanine nucleotides, inhibition of bacterial IMPDH could be an excellent opportunity to tackle the bacterial infections.26,28,38 The multiple sequence alignment of these pathogenic bacterial IMPDHs gave a clear understanding of conserved and non-conserved residues. IMPDH in all these bacteria has a sequence similarity of >80% (Fig. 4). Even though IMPDHs from all the pathogenic bacteria are similar in sequence and structure, the prokaryotic and eukaryotic IMPDH enzymes differ significantly in their kinetic properties and sensitivity to inhibitors. The structural analysis of IMPDHs has revealed that IMP and nicotinamide riboside binding sites are highly conserved in IMPDHs of different classes. In contrast, the adenosine and pyrophosphate subunits of NAD+ binding sites diverge in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. A detailed discussion on the divergence of binding sites can be found in an earlier report.39 Owing to these structural, kinetic and substrate affinity differences in the eukaryotic and prokaryotic IMPDH enzymes, selective inhibition of bacterial IMPDH is possible.3,39,40 This makes bacterial IMPDH a very attractive target and hence it is currently one of the widely sought-after targets for investigation of novel antibiotics. One example of such selectivity due to differences in the bacterial IMPDH and host IMPDH includes classical human IMPDH II inhibitor mycophenolic acid (MPA). MPA has around 1000 times higher affinity towards IMPDH II over prokaryotic IMPDHs.4

Fig. 4. Multiple sequence alignment of pathogenic bacterial IMPDH. The yellow color indicates the conserved amino acid in the sequence, while the red color indicates conservation of residues in all the sequences presented here. The following sequences have been used for the protein sequence alignment of Mycobacterium leprae, Borrelia burgdorferi (Bb), Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Acinetobacter baumannii, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Bacillus anthracis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, Cryptosporidium parvum, Campylobacter jejuni, and Helicobacter pylori (Hp).

As shown by Liechti et al., certain pathogens such as H. pylori rely mainly on the salvage pathway for survival, where these pathogens can salvage xanthine, which can then be easily converted to XMP with the help of the enzyme xanthine-phosphoribosyl-transferase (XPRT) and further utilized for generation of GMP pool.41 In such instances the use of IMPDH inhibitors could be challenging. Despite this fact, several in vitro and in vivo studies have shown very promising results for IMPDH as a potential target to treat infections. One such study by Gorla et al. showed efforts made toward validation of IMPDH as a target. In this work, in vivo studies were performed using eight selective and potent inhibitors of Cryptosporidium parvum IMPDH (CpIMPDH) in an IL-12 knockout mouse model to mimic the acute cryptosporidiosis in humans. These results showed very promising in vivo anti-parasitic activity.42

Based on these observations and the potential of this excellent target, several efforts have been made to study the structural effects of the small molecule inhibitors on the potency and selectivity over the host IMPDH. Discussed below are the recent developments in the field of small molecule inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH.

Development of inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH

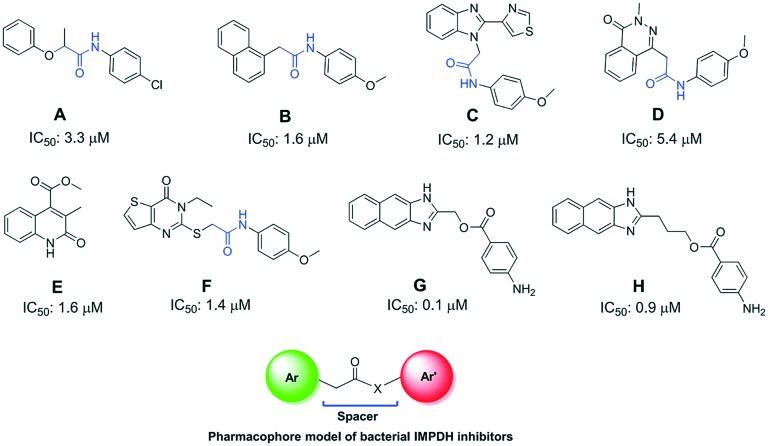

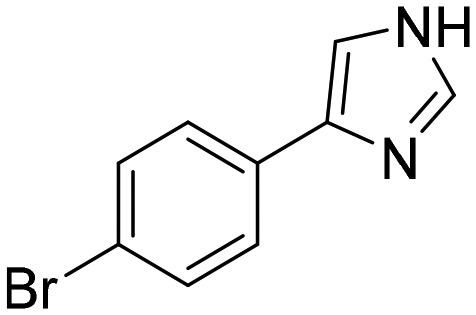

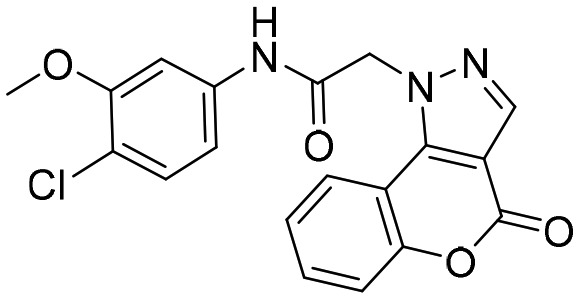

1. High-throughput screening of compounds A–H

One of the earliest reports on pathogenic IMPDH inhibitors includes the screening of small molecules against CpIMPDH. These high throughput screens revealed highly selective CpIMPDH inhibitors targeting highly diverged NAD binding sites. A total of 10 highly potent and selective compounds were identified, out of which eight compounds, A–H, were very promising with diversified structures (Fig. 5).40,43 All these molecules were the first structural determinants for the selective inhibition of pathogenic IMPDH over host IMPDH II. These inhibitors were confirmed to bind to the NAD+ and nicotinamide subsites.

Fig. 5. Reported CpIMPDH inhibitors A–H and their inhibition potencies.

As can be seen from Fig. 5, all the reported A–H molecules screened against CpIMPDH have the distinct structural feature of 2 aromatic rings separated by a spacer or a linker (except compound E). A pharmacophore model deduced from the structures of these molecules is given in Fig. 5. In compounds A–D and F this spacer is an acetamido group (marked in blue) which can also be seen in the newer molecules investigated later. Hedstrom et al. have given detailed medicinal chemistry of these molecules along with the inhibitory potential of these molecules against other pathogenic IMPDHs such as H. pylori IMPDH (HpIMPDH), B. burgdorferi IMPDH (BbIMPDH) and S. pyogenes IMPDH (SpIMPDH).4 The compounds which exhibited good inhibition from the screening were further co-crystallised with different bacterial IMPDHs (Table 1). These crystal structures give key information on the binding interactions of inhibitors with the bacterial IMPDHs.

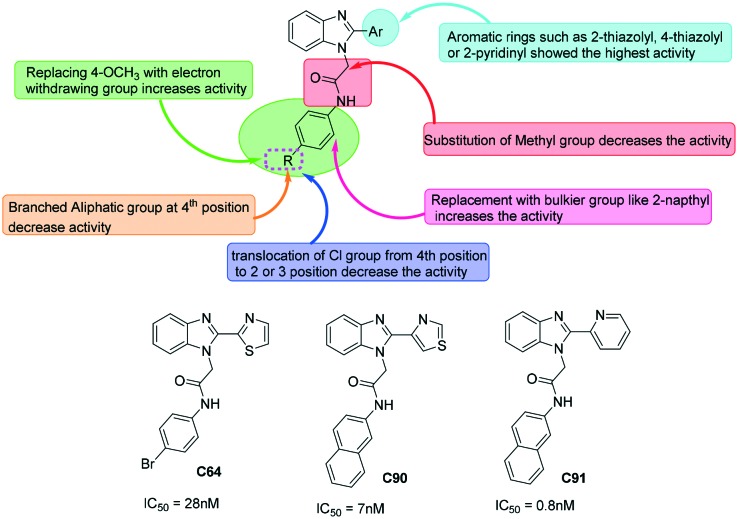

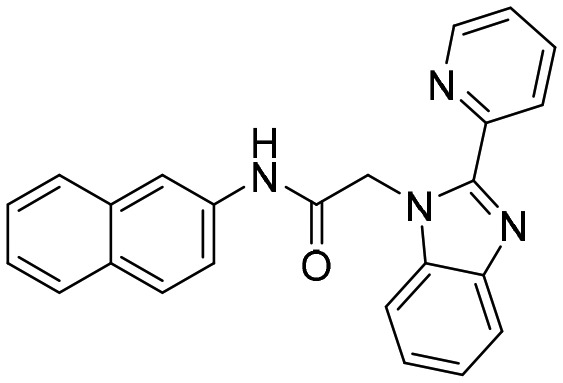

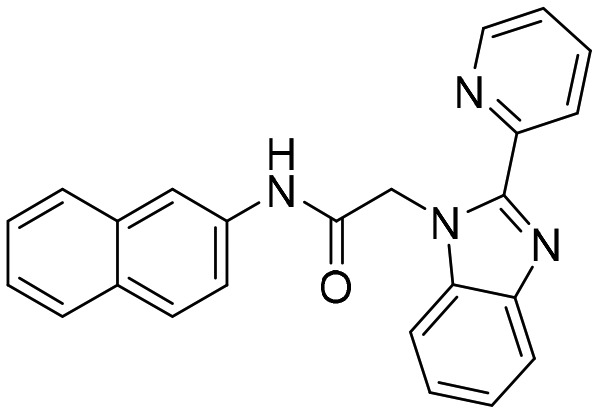

2. Benzimidazoles as potent inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH

With aim of further optimizing the series, A–H compounds, compound C was further modified with different aromatic rings at position 2 of the benzimidazole scaffold and at the acetamido linker.38,44 Fig. 6 gives the detailed structure–activity relationship derived from the literature on benzimidazole-based molecules as bacterial IMPDH inhibitors. So far several benzimidazole-based molecules have been studied for their inhibitory potential against bacterial IMPDHs. In pursuit of finding potent and selective IMPDH inhibitors, several substitution patterns on the benzimidazole scaffold were investigated. This includes replacement of the 4-thiazolyl ring with 2-thiazolyl or 2-pyridinyl substitution at position 2 of benzimidazole. Along with these, several heterocycles such as substituted phenyl and naphthyl rings were investigated at the acetamido linker for their effect on the activity. It was found that at anilide substitution, replacing 4-methoxy of compound C with thiomethyl or electron withdrawing groups led to a substantial increase in the activity. Also, replacing the phenyl ring with bulkier and hydrophobic groups such as a naphthyl ring led to a strong increase in the inhibitory potential. Relocation of halogens (chloro and bromo) from position 4 to 2 or 3 of the anilide group led to a decrease in activity.44 These studies resulted in the identification of C64 and C91 as the most promising molecules with IC50 values against CpIMPDH and HpIMPDH in the nanomolar range. These compounds showed a very high selectivity over host IMPDH II.

Fig. 6. SAR of benzimidazoles and selected molecules as inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH. Structures of representative potent molecules, C64, C90, and C91, given their IC50 values against CpIMPDH.

In the study carried out by Gollapalli et al., C91 was found to be the most potent inhibitor of CpIMPDH, HpIMPDH, and SpIMPDH (data obtained by a tight-binding equation) with no inhibitory effect against host IMPDH.40 Several crystal structures of bacterial IMPDHs such as Campylobacter jejuni [PDB ID: ; 4MZ8], Bacillus anthracis IMPDH [PDB ID: ; 4MY9] and Clostridium perfringens [PDB ID: ; 4Q33] with C91 have been reported45–47 (Table 1). These reports suggest an interaction of C91 with Glu290 by a hydrogen bond which is a key interaction between prokaryotic IMPDHs and C91 like compounds. This residue is conserved in prokaryotic IMPDH but is replaced by Ser290 in HsIMPDH-II.28 This can clearly give the reasoning for species specific inhibitors having selectivity over the host.

C91 has been reported to be a non-competitive inhibitor against both IMP and NAD+ binding sites.28 The non-competitive inhibition of C91 is advantageous as in such cases the inhibition will be independent of the substrate concentration. Also, competitive IMPDH inhibitors with respect to the IMP binding site lack selectivity over the host and hence uncompetitive and non-competitive inhibitors are much preferable. Even though C91, a benzimidazole molecule, is still the most potent inhibitor known for CpIMPDH and HpIMPDH, its clinical use was limited due to the rather poor metabolic profile of benzimidazoles. Nonetheless, benzimidazole-based molecules were the first most potent CpIMPDH and HpIMPDH inhibitors and can work as lead molecules for further development of bacterial IMPDH inhibitors.

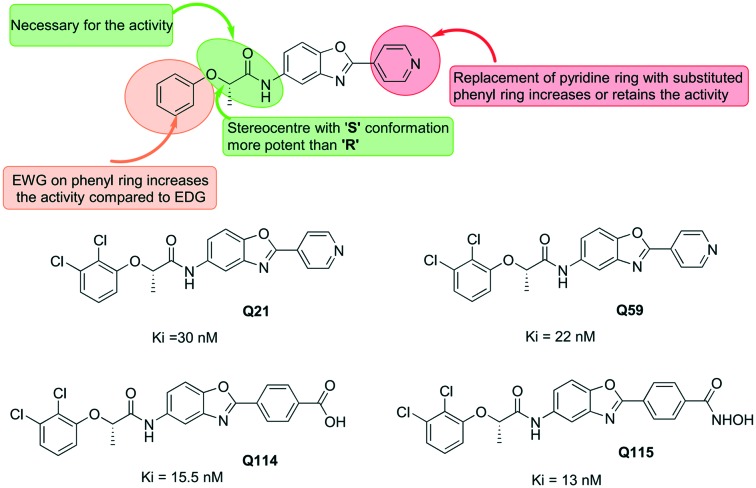

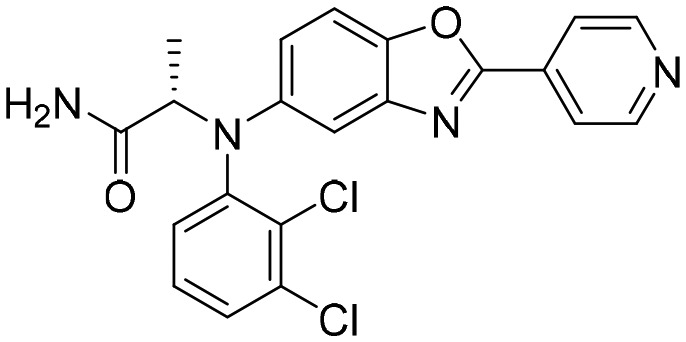

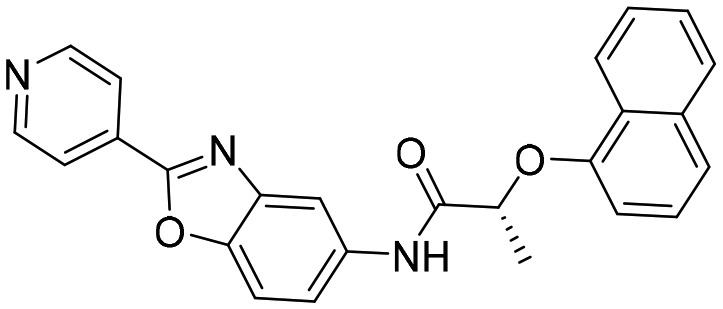

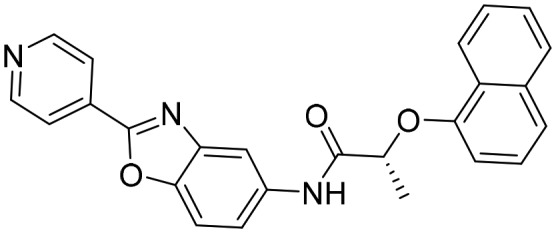

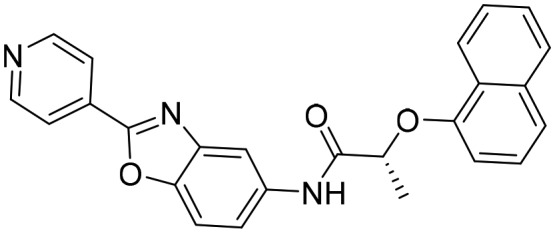

3. Benzoxazoles as inhibitors of bacterial IMPDH

Gorla et al. reported the SAR of a series of benzoxazole-based CpIMPDH inhibitors having IC50 values in the nanomolar range.22 These molecules showed over 500-fold selectivity over host IMPDH II. In this study, it was also observed that benzoxazole-based molecules bind to the NAD+ site competitively. Amongst the molecules investigated in the study, the ones having pyridinyl or a small heteroaromatic substituent at position 2 of the benzoxazole showed better activity. Further, benzoxazole-based molecules were studied for their inhibitory potential against F. tularensis IMPDH (FtIMPDH).48 The structure–activity relationship of these compounds was found to be similar to that for the CpIMPDH inhibition (Fig. 7). The inhibitory potential of benzoxazole-based molecules was found to be around 6-fold less potent against FtIMPDH than that of the CpIMPDH inhibition. Gorla et al. also reported the co-crystallisation of different small molecules with CpIMPDH and BaIMPDH.22 In this work, benzoxazole-based molecule Q21 was co-crystallised with CpIMPDH (Table 1) and it was found that the methyl group in the molecule interacts with Met308 and Met326. The carbonyl oxygen and pyridine nitrogen were found to form water-mediated hydrogen bonds with the main chain containing Met326, Asn171, and Ser354. With respect to IMP, the Q21 molecule was found to be non-competitive and uncompetitive against BaIMPDH and CpIMPDH, respectively.

Fig. 7. SAR of benzoxazole-based IMPDH inhibitors with representative molecules. Ki values of selective molecules are given against FtIMPDH.

Very recently, Chacko et al. reported further optimization of benzoxazole-based molecules against M. tuberculosis IMPDH (MtbIMPDH2).49 This work demonstrated the effectiveness of benzoxazole-based MtbIMPDH2 inhibitors to have antibacterial activity with an MIC value of around 1 μM. One of the most potent compounds in the series Q151 showed an IC50 value of 18 nM against MtbIMPDH2 with an MIC value of 1.5 μM. These molecules were also found to be highly selective over host IMPDH II. The most important finding of this work is the ability of these compounds to inhibit the microbial growth even in the presence of guanine, which M. tuberculosis (Mtb) could salvage. This suggested the great potential of MtbIMPDH2 as a vulnerable target to treat drug-resistant tuberculosis.

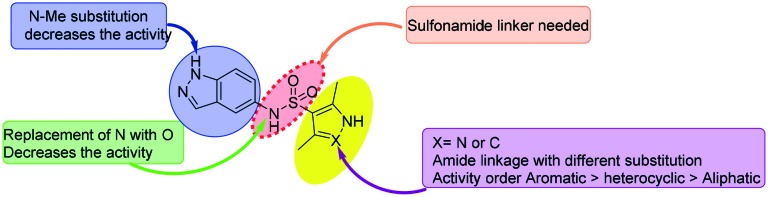

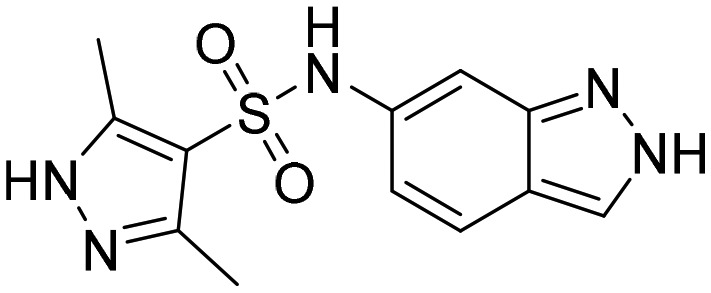

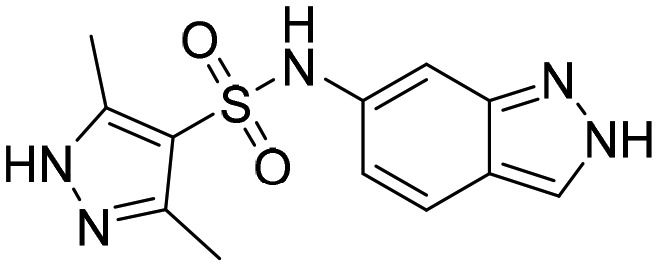

4. Indazoles as IMPDH inhibitors

Indazole-based molecules (indazole sulphonamides) were recently screened for their effectiveness against MtbIMPDH2 inhibitors with low micromolar potency against Mtb.50 Unfortunately, these molecules did not affect the high lesional levels of guanine and had a slow lytic effect posing challenges to develop drugs against MtbIMPDH2 for treating tuberculosis. Nonetheless, this study revealed a new class of bacterial IMPDH inhibitors which can be further optimized. The SAR studies derived from this work are shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. SAR of indazole sulphonamide-based IMPDH inhibitors. The MIC of potent compounds against Mtb H37Rv is given.

From the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) data reported, it can be seen that the basic indazole sulphonamide scaffold was required for the activity. Methyl substitution on the indazole basic nitrogen led to a drastic decrease in the activity. Indazole-based small molecule TBK6 has been co-crystallised with MtbIMPDH (PDB ; 5UPU, Table 1) in the presence of IMP. The compound can be found in the co-factor binding pocket.

In another study, replacement of sulphonamide nitrogen with oxygen led to a sharp decrease in activity. These studies can certainly serve as a lead for further development of potent and selective IMPDH inhibitors.

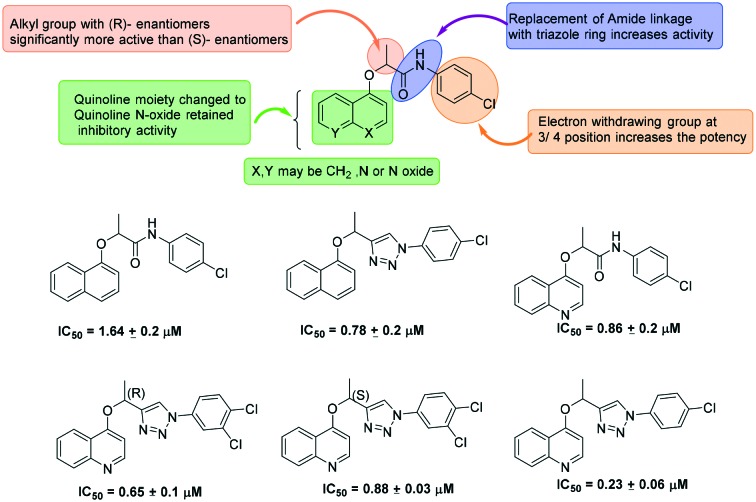

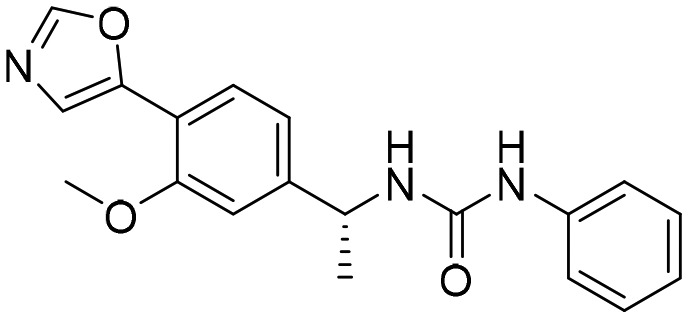

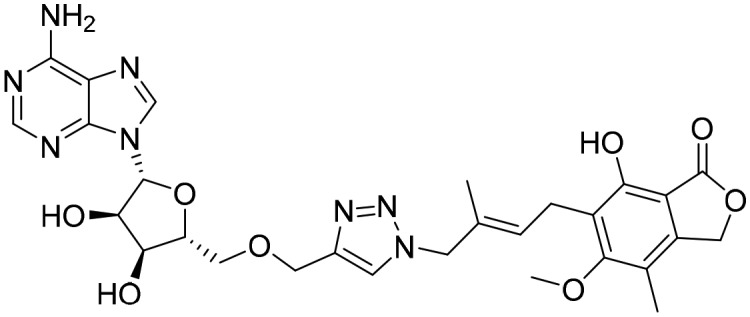

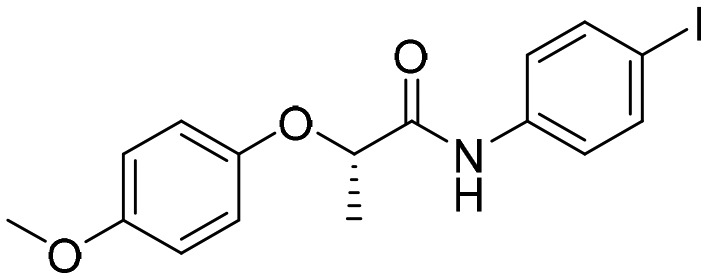

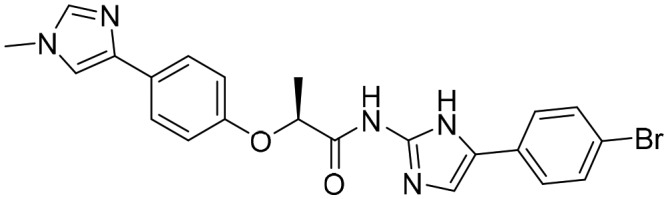

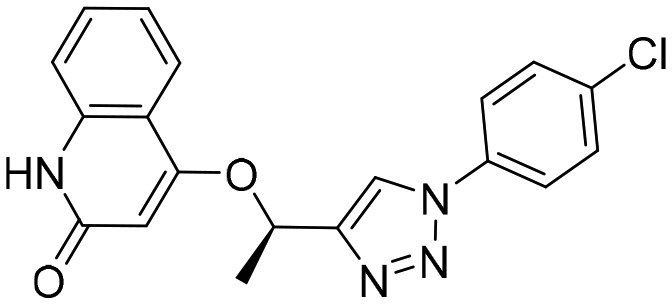

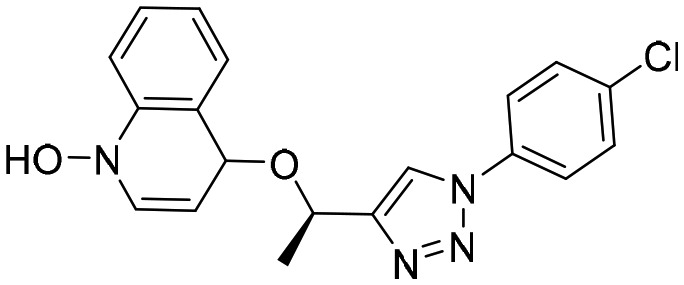

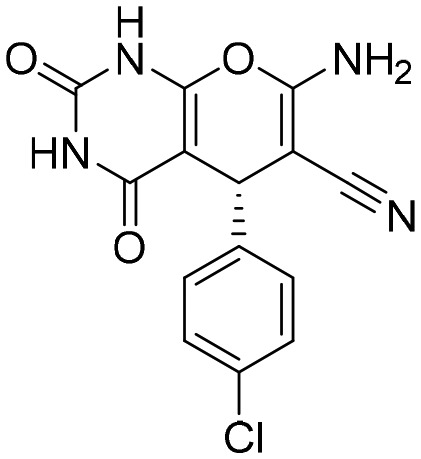

5. 1,2,3-Triazoles as IMPDH inhibitors

1,2,3-Triazoles have been extensively studied as potential CpIMPDH and MtbIMPDH inhibitors. A series of 1,2,3-triazoles containing ether linkages were investigated by Maurya et al. for their inhibitory effect on CpIMPDH.51 In the initial studies, an amide derivative with a fused ring onto the phenyl ether (Fig. 9) was found to have good CpIMPDH inhibitory activity. These molecules were further modified and the SAR studies revealed the importance of the small alkyl substitution on the alpha position to the ether for the enhanced potency (Fig. 9). In this study, it was also found that this small alkyl group with an R-enantiomer was significantly more active than the S-enantiomer. Further, the presence of an electron withdrawing group at the 3rd/4th position of the anilido phenyl ring leads to increase in the IMPDH inhibition. These molecules were found to be a good lead for further development of parasitic or pathogenic IMPDH inhibitors.

Fig. 9. Development of 1,2,3-triazole-based inhibitors of IMPDH.

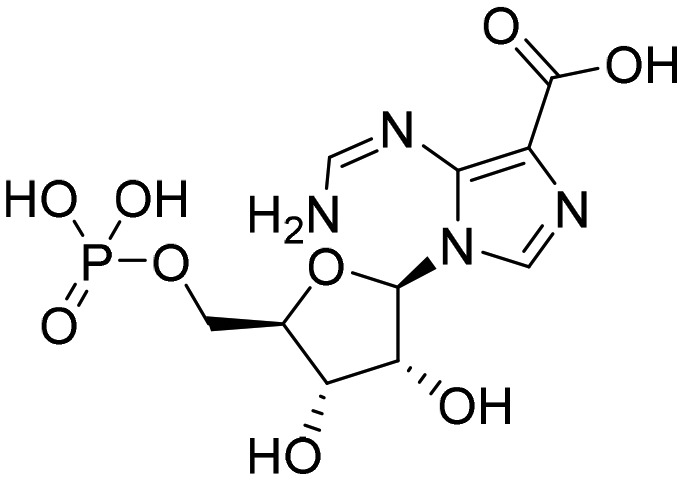

Later, Chen et al. reported the discovery of 1,2,3-triazole-linked mycophenolic adenine dinucleotide (MAD) derivatives as the first potent inhibitors of MtbIMPDH (Ki = 1 μM) at that time.52 It was suggested that the length of the linker plays a key role in the activity. One of the key outputs of the studies was the effect of the structural variations on the host IMPDH and MtbIMPDH on the inhibition.

Triazole-based molecule A110 has been co-crystallised with B. anthracis (PDB ; 4MYA, Table 1) and was found to inhibit BaIMPDH in a non-competitive manner with respect to both IMP and NAD+.53

Very recently, Sahu et al. reported hit discovery of molecules with a 1,2,3-triazole scaffold against MtbIMPDH.54 These included 1-benzyl triazole derivatives. Only a few molecules were able to show appreciable MtbIMPDH inhibition with an MIC value of around 50 μM. These triazole hits despite having appreciable anti-Mycobacterium tuberculosis activity failed to show a direct correlation with GuaB2 (IMPDH2) inhibition. The same research group reported inhibition of HpIMPDH using several triazole molecules.55 The molecules having an oxadiazole-phenyl substituent on the linker showed good inhibitory potential against HpIMPDH with inhibition ranging from 55% to 99.8%. The most potent compound showed an IC50 value of 4.06 μM. Despite low potency, these hits are the exciting starting point for further enhancing the potency and selectivity of these molecules.

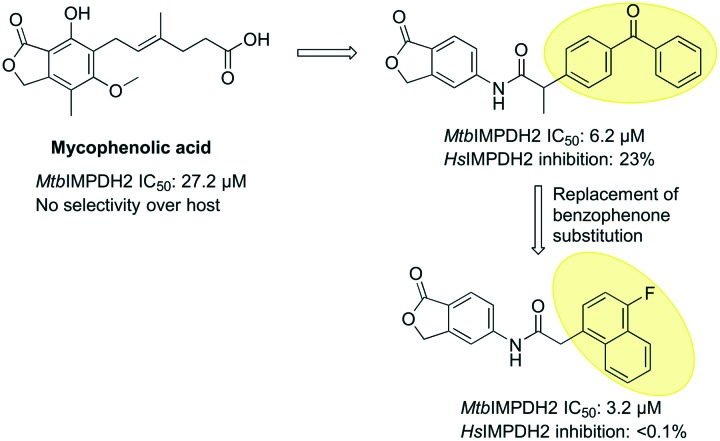

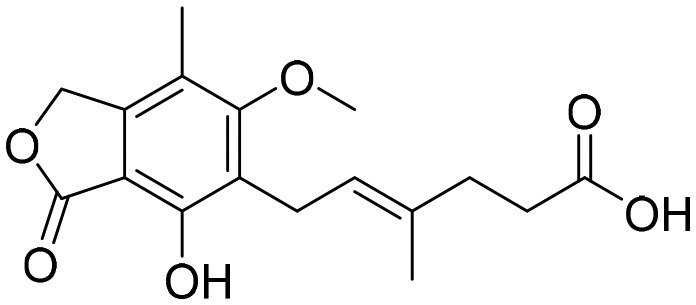

6. Isobenzofurans (phthalides) as IMPDH inhibitors

A classical IMPDH inhibitor mycophenolic acid belongs to the isobenzofuran class of compounds and is widely used as an antiviral and immunosuppressant drug. The mycophenolic acid adenine nucleotide derivative MAD1 is a third generation IMPDH inhibitor and the first inhibitor reported for MtbIMPDH2.17 MAD1 has been shown to be an uncompetitive inhibitor of IMPDH with respect to IMP and NAD+. MAD1 has also been co-crystallised with MtbIMPDH, which gives insight into its binding (PDB ID: ; 4ZQP, Table 1). MAD1 interacts with IMP forming hydrogen bonds with residues T343, G334 and G336. These residues are conserved in all IMPDHs including HsIMPDH2, suggesting a possible loss of selectivity over host IMPDH.

Recently, the mycophenolic scaffold was further modified to identify new and selective inhibitors of MtbIMPDH2 wherein an acetamido linker was introduced at the 5th position of the phthalide ring (Fig. 10). Out of all compounds screened two molecules having benzophenone and naphthyl substituents on the acetamido linker were found to be active in screening against Mtb and showed activity against MtbIMPDH2. Unlike mycophenolic acid, the compound with naphthyl substitution showed selectivity over host IMPDH while inhibiting MtbIMPDH with an IC50 value of 3.2 μM.

Fig. 10. Isobenzofurans (phthalides) as IMPDH inhibitors.

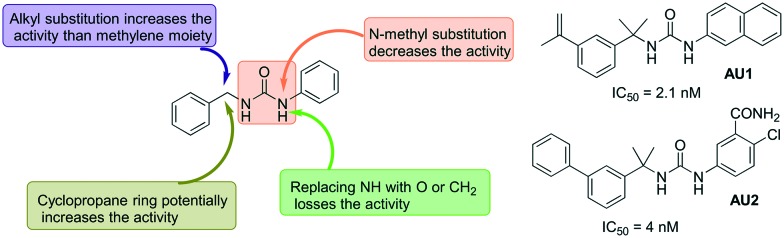

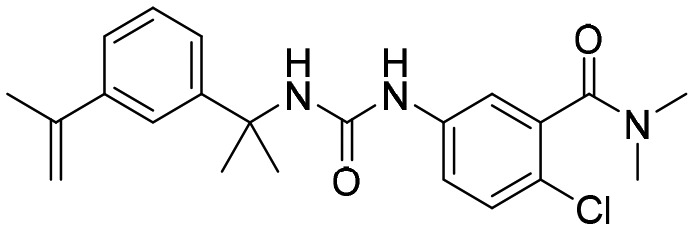

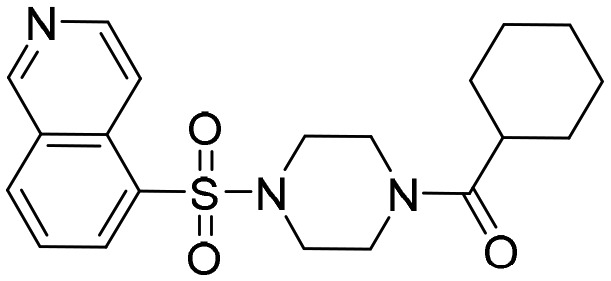

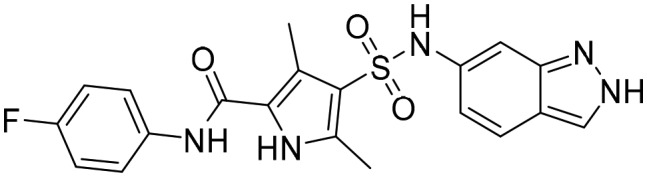

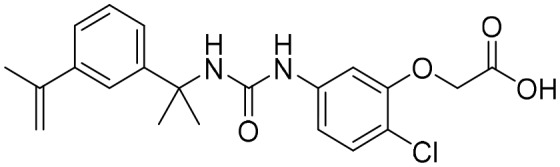

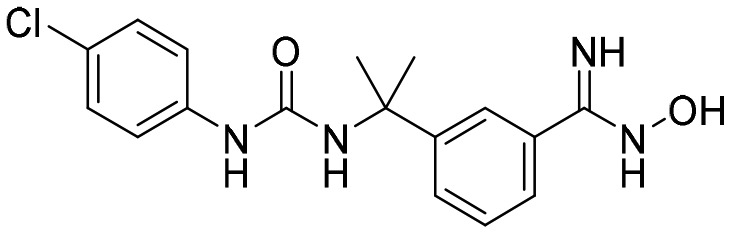

7. Arylurea derivatives as IMPDH inhibitors

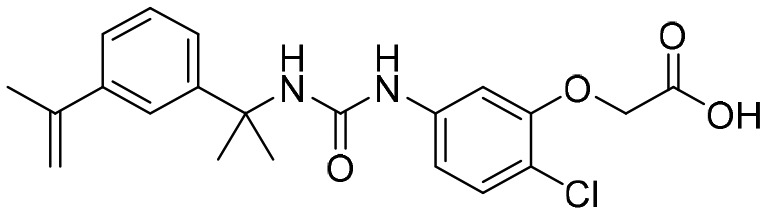

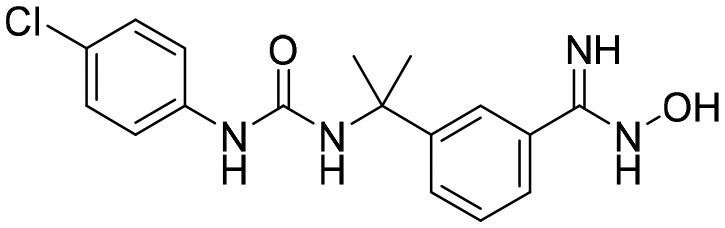

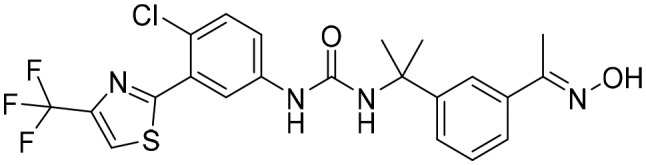

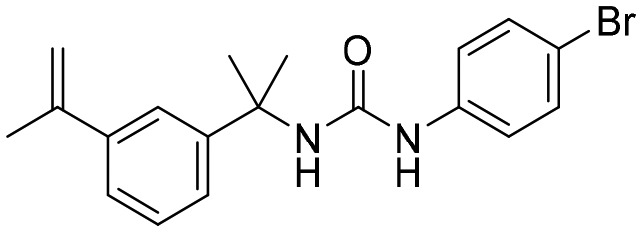

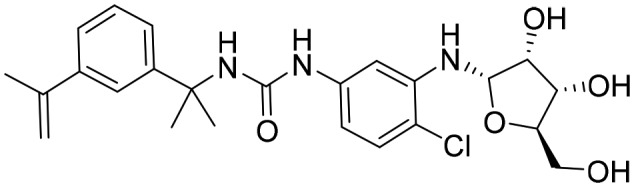

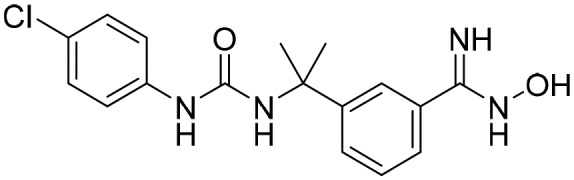

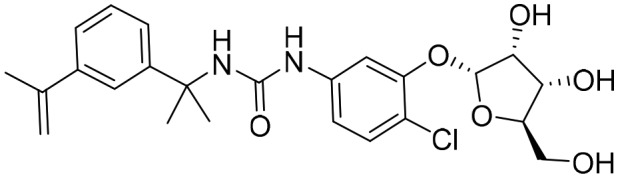

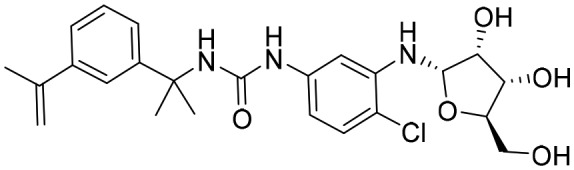

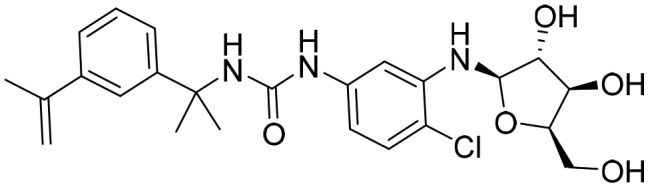

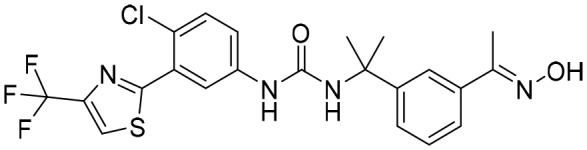

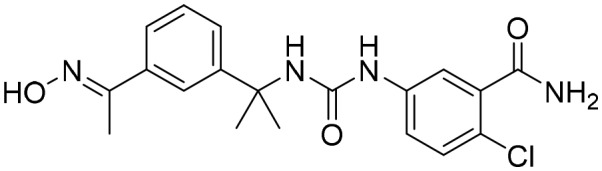

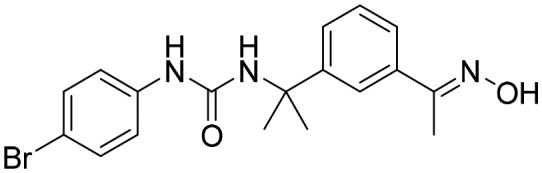

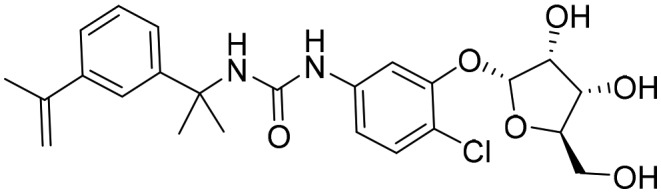

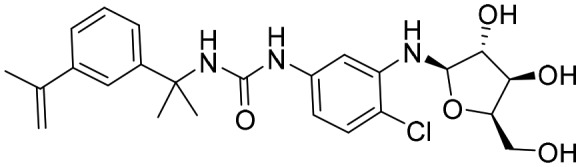

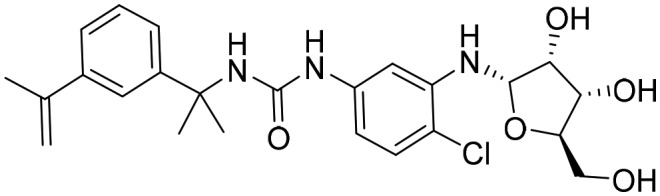

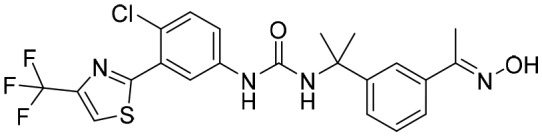

One of the early reports on the use of aryl ureas includes the work of Usha et al., where 16 diphenyl ureas were screened against MtbIMPDH 2.56 This study revealed three interesting molecules with more than 90% inhibition at 1 μM concentration. These molecules were also found to have anti-TB activity when studied against Mtb and M. smegmatis with low MIC values. Another report from Gorla et al. described an investigation of different aryl ureas for their inhibitory effect against CpIMPDH.57 Some of the aryl urea derivatives investigated were found to be very at concentration as low as 2 nM against CpIMPDH with more than 1000 fold selectivity over human IMPDH II. From the SAR studies, it was revealed that 3,4-disubstitution or 3,4-ring fusion at the anilide position led to a significant increase in the inhibitory potency. The urea nitrogen was important for the activity, and replacement with oxygen or carbon led to the loss of activity. The other nitrogen of the urea could be replaced with oxygen while retaining the activity (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Arylurea derivatives as IMPDH inhibitors, half maximal inhibitory concentrations against CpIMPDH are given for selected (AU1 and AU2) molecules.

In recent work, by the same group, aryl urea-based molecules were investigated further for their antibacterial effect against FtIMPDH. Two of the aryl urea compounds displayed antibacterial activity with MIC less than or equal to 10 μM. These results are encouraging for the future development of IMPDH inhibitors to treat infectious diseases.

So far, several crystal structures of IMPDH have been reported which have been co-crystallised with different aryl urea molecules. These include co-crystallised structures of C. jejuni, B. anthracis and Mtb with aryl ureas such as P12, P32, P41, etc. (Table 1). Molecule P32 has been shown to inhibit BaIMPDH in a non-competitive manner with respect to both IMP and NAD+.53

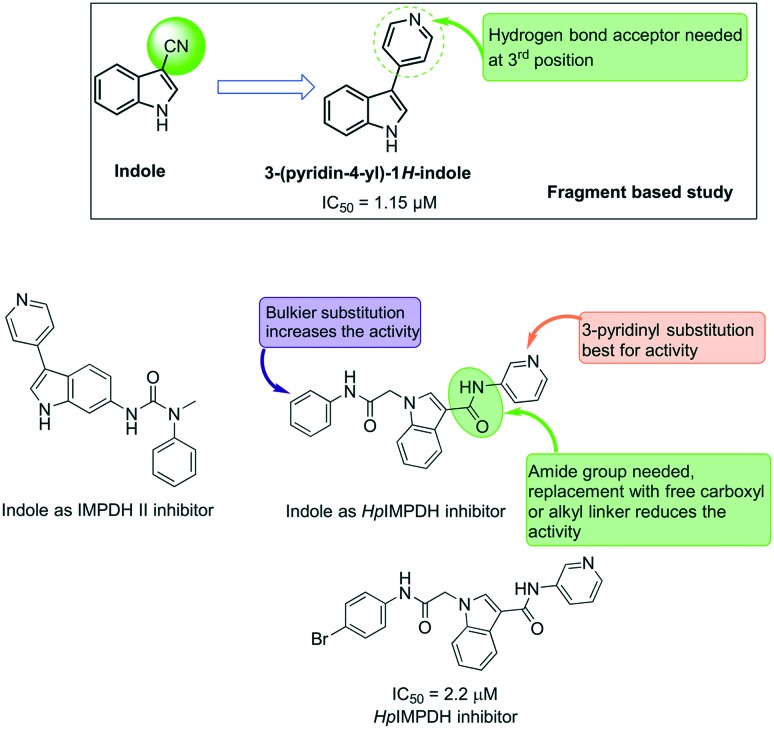

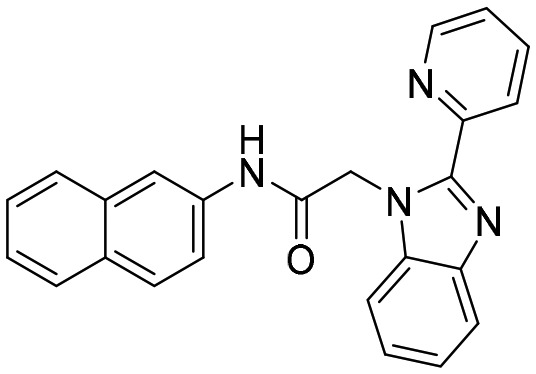

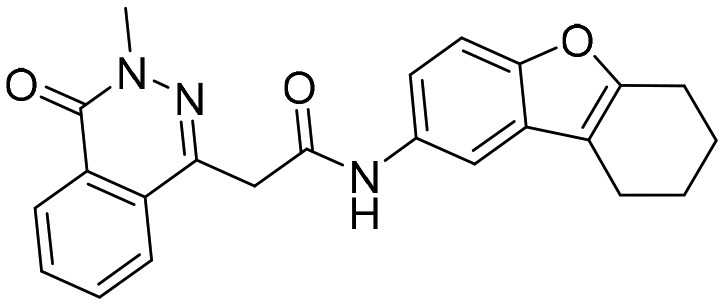

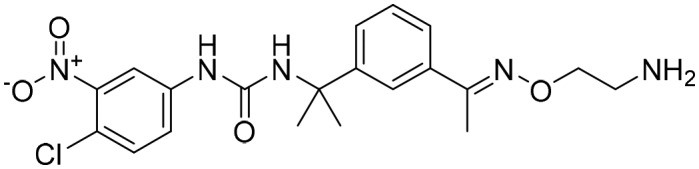

8. Indoles as IMPDH inhibitors

Indole-based molecules have been investigated in the past for their inhibitory effect on the host IMPDH II.58–60 In 2006, Beevers et al. highlighted indole-based small molecules as non-oxazole-based IMPDH II inhibitors against human IMPDH II.59 In their study, they have identified commercially available 3-CN indole as an IMPDH II inhibitor with an IC50 value of 20 μM (indole). Further, they have explored a series of indole derivatives with a hydrogen bond acceptor at the 3rd position of indole as IMPDH II inhibitors and identified 3-pyrid-4yl indole as a potent compound in the sub micromolar range (IC50 of 1.15 μM) from the fragment-based study.

One of the distinct features of these human IMPDH inhibitors is the lack of an acetamido linker needed for the prokaryotic IMPDH inhibition. When compared to our very recently reported indole-based HpIMPDH inhibitors,28 IMPDH II inhibitors lack bulky substitution at the basic nitrogen of indole. The structural features of indole-based HpIMPDH include the presence of an acetamido linker at position one and a second linker connected to the aromatic ring at position 3 of the indole scaffold. In this study, it was observed that the presence of bulkier substitution at the acetamido linker led to an increase in activity, while the presence of the amide group at position 3 was essential for HpIMPDH inhibition. Replacement of this amide linker with a free carboxyl group or a flexible alkyl linker led to a sharp decrease in the activity.

These studies also highlighted the binding mode of indole-based HpIMPDH, wherein the most potent compound in the series (Fig. 12) was found to have a non-competitive inhibitory effect against both the IMPDH substrates IMP and NAD+. Such molecules have an advantage that the inhibitory effect of these compounds will not be affected by the increase in the substrate concentration, a mechanism used by the bacteria to gain drug resistance. With the aim of further developing these molecules, we have investigated new indole-based HpIMPDH inhibitors wherein the amide group at position 3 of the indole was replaced with a diazo substituent. These molecules were found to have a moderate inhibitory effect against HpIMPDH61 and hold great promise for further development of potent and selective inhibitors of bacterial IMPDHs.

Fig. 12. Indole-based molecules as IMPDH inhibitors.

Conclusions and future perspective

IMPDH is an excellent target which is still unexplored to its full potential for treating infectious diseases. The literature reveals strong evidence for its applicability as a new target for treating drug-resistant pathogenic infections. Several studies have been carried out to investigate the structural effects, inhibitory potential, and kinetics of different scaffolds. These studies have also revealed the important structural features needed for the selectivity over the host IMPDH II enzyme. Although notable information on the prokaryotic IMPDH inhibitors is available, further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to test the real potential of IMPDH inhibitors to treat infectious diseases. One of the advantages of the similarity in the IMPDH binding sites amongst several bacteria is the possibility of identifying broad-spectrum antimicrobials. IMPDH holds great promise as a novel target for treating infectious diseases which are now becoming resistant to the currently available therapies.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgments

SK would like to thank Science and engineering research Board (SERB) and DST Ramanujam fellowship the funding. KJ would like to thank SERB for the ECR award (ECR/2016/001962). We would like to thank Prof. Vijay Thiruvenkatam for valuable suggestions and discussions. We also thank Mr. Sachin Puri for his kind help in preparing illustrations. KJ and AS thank IIT Gandhinagar for financial support and facilities.

Footnotes

†The authors would like to dedicate this article to Prof. D. N. Rao, Professor, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India.

References

- Shah C. P., Kharkar P. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;158:286–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munita J. M., Arias C. A. Microbiol. Spectrum. 2016;4(2):VMBF-0016-2015. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0016-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah C. P., Kharkar P. S. Future Med. Chem. 2015;7:1415–1429. doi: 10.4155/fmc.15.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L., Liechti G., Goldberg J. B., Gollapalli D. R. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011;18:1909–1918. doi: 10.2174/092986711795590129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrelli R., Vita P., Torquati I., Felczak K., Wilson D. J., Franchetti P. and Cappellacci L., Recent patents on anti-cancer drug discovery, 2013, vol. 8, pp. 103–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuny G. D., Suebsuwong C., Ray S. S. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017;27:677–690. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1280463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamsen M. S., Templeton T. J., Enomoto S., Abrahante J. E., Zhu G., Lancto C. A., Deng M., Liu C., Widmer G., Tzipori S., Buck G. A., Xu P., Bankier A. T., Dear P. H., Konfortov B. A., Spriggs H. F., Iyer L., Anantharaman V., Aravind L., Kapur V. Science. 2004;304:441–445. doi: 10.1126/science.1094786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:545–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. C., Weber G., Morris H. P. Nature. 1975;256:331–333. doi: 10.1038/256331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert H. J., Lowe C. R., Drabble W. T. Biochem. J. 1979;183:481–494. doi: 10.1042/bj1830481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager P. W., Collart F. R., Huberman E., Mitchell B. S. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1995;49:1323–1329. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)00026-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter D. G., Witkowski J. T., Khare G. P., Sidwell R. W., Bauer R. J., Robins R. K., Simon L. N. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1973;70:1174–1178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakawa N., Matsuda A. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:615–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:545–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby T. D., Vanderveen K., Strickler M. D., Markham G. D., Goldstein B. M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:3531–3536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sintchak M. D., Nimmesgern E. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47:163–184. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowska-Grzyska M., Kim Y., Gorla S. K., Wei Y., Mandapati K., Zhang M., Maltseva N., Modi G., Boshoff H. I., Gu M., Aldrich C., Cuny G. D., Hedstrom L., Joachimiak A. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapero A., Pacitto A., Singh V., Sabbah M., Coyne A. G., Mizrahi V., Blundell T. L., Ascher D. B., Abell C. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:2806–2822. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Donini S., Pacitto A., Sala C., Hartkoorn R. C., Dhar N., Keri G., Ascher D. B., Mondésert G., Vocat A., Lupien A., Sommer R., Vermet H., Lagrange S., Buechler J., Warner D. F., McKinney J. D., Pato J., Cole S. T., Blundell T. L., Rizzi M., Mizrahi V. ACS Infect. Dis. 2017;3:5–17. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Pacitto A., Bayliss T., Cleghorn L. A. T., Wang Z., Hartman T., Arora K., Ioerger T. R., Sacchettini J., Rizzi M., Donini S., Blundell T. L., Ascher D. B., Rhee K., Breda A., Zhou N., Dartois V., Jonnala S. R., Via L. E., Mizrahi V., Epemolu O., Stojanovski L., Simeons F., Osuna-Cabello M., Ellis L., MacKenzie C. J., Smith A. R. C., Davis S. H., Murugesan D., Buchanan K. I., Turner P. A., Huggett M., Zuccotto F., Rebollo-Lopez M. J., Lafuente-Monasterio M. J., Sanz O., Diaz G. S., Lelièvre J., Ballell L., Selenski C., Axtman M., Ghidelli-Disse S., Pflaumer H., Bösche M., Drewes G., Freiberg G. M., Kurnick M. D., Srikumaran M., Kempf D. J., Green S. R., Ray P. C., Read K., Wyatt P., Barry C. E., Boshoff H. I. ACS Infect. Dis. 2017;3:18–33. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Makowska-Grzyska M., Gorla S. K., Gollapalli D. R., Cuny G. D., Joachimiak A., Hedstrom L. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. F: Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2015;71:531–538. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X15000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorla S. K., Kavitha M., Zhang M., Chin J. E., Liu X., Striepen B., Makowska-Grzyska M., Kim Y., Joachimiak A., Hedstrom L., Cuny G. D. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:4028–4043. doi: 10.1021/jm400241j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre T., Lupan A., Helynck O., Vichier-Guerre S., Dugué L., Gelin M., Haouz A., Labesse G., Munier-Lehmann H. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;167:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L., Petsko G. A., Hedstrom L. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13309–13317. doi: 10.1021/bi0203785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmesgern E., Black J., Futer O., Fulghum J. R., Chambers S. P., Brummel C. L., Raybuck S. A., Sintchak M. D. Protein Expression Purif. 1999;17:282–289. doi: 10.1006/prep.1999.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowska-Grzyska M., Kim Y., Wu R., Wilton R., Gollapalli D. R., Wang X. K., Zhang R., Jedrzejczak R., Mack J. C., Maltseva N., Mulligan R., Binkowski T. A., Gornicki P., Kuhn M. L., Anderson W. F., Hedstrom L., Joachimiak A. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6148–6163. doi: 10.1021/bi300511w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N., Wang J., Li J., Wang Q. H., Wang Y., Cheng M. S. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2011;78:175–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvale K., Purushothaman G., Singh V., Shaik A., Ravi S., Thiruvenkatam V., Kirubakaran S. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:190. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37490-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Robinson D., Whytock S., Green C. J., Carney Jr. F. E. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 1974;50:279–288. doi: 10.1136/sti.50.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J. A. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:114. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers E. J. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;13(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lastória J. C., Abreu M. A. M. M. D. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014;89:205–218. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A., Mizrahi V. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:555–556. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques-Normark B., Tuomanen E. I. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Med. 2013;3:a010215. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. J., Barnett T. C., McArthur J. D., Cole J. N., Gillen C. M., Henningham A., Sriprakash K. S., Sanderson-Smith M. L., Nizet V. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014;27:264. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00101-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R. C. J. Clin. Pathol. 2003;56:182–187. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.3.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury M. N. Trop. Geogr. Med. 1984;36:215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson I. S., Kirubakaran S., Gorla S. K., Riera T. V., D'Aquino J. A., Zhang M., Cuny G. D., Hedstrom L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1230–1231. doi: 10.1021/ja909947a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedstrom L. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2903–2928. doi: 10.1021/cr900021w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollapalli D. R., Macpherson I. S., Liechti G., Gorla S. K., Goldberg J. B., Hedstrom L. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liechti G., Goldberg J. B. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:839–854. doi: 10.1128/JB.05757-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorla S. K., McNair N. N., Yang G., Gao S., Hu M., Jala V. R., Haribabu B., Striepen B., Cuny G. D., Mead J. R., Hedstrom L. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:1603–1614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02075-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umejiego N. N., Gollapalli D., Sharling L., Volftsun A., Lu J., Benjamin N. N., Stroupe A. H., Riera T. V., Striepen B., Hedstrom L. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirubakaran S., Gorla S. K., Sharling L., Zhang M., Liu X., Ray S. S., Macpherson I. S., Striepen B., Hedstrom L., Cuny G. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1985–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Makowska-Grzyska M., Gu M., Anderson W. F. and Joachimiak A., RSC PDB, 2013, 10.18430/M34MY9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maltseva N., Kim Y., Makowska-Grzyska M., Mulligan R., Gu M., Zhang M., Mandapati K., Gollapalli D. R., Gorla S. K., Hedstrom L., Anderson W. F. and Joachimiak A., RSC PDB, 2014, 10.2210/pdb4q32/pdb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Makowska-Grzyska M., Gu M., Gorla S. K., Hedstrom L., Anderson W. F. and Joachimiak A., Csgid, Center for Structural Genomics of Infectious Diseases, 2013, 10.2210/pdb4mz8/pdb. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorla S. K., Zhang Y., Rabideau M. M., Qin A., Chacko S., House A. L., Johnson C. R., Mandapati K., Bernstein H. M., McKenney E. S., Boshoff H., Zhang M., Glomski I. J., Goldberg J. B., Cuny G. D., Mann B. J., Hedstrom L. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e00939. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00939-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko S., Boshoff H. I. M., Singh V., Ferraris D. M., Gollapalli D. R., Zhang M., Lawson A. P., Pepi M. J., Joachimiak A., Rizzi M., Mizrahi V., Cuny G. D., Hedstrom L. J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:4739–4756. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y., Pacitto A., Bayliss T., Cleghorn L. A., Wang Z., Hartman T., Arora K., Ioerger T. R., Sacchettini J., Rizzi M., Donini S., Blundell T. L., Ascher D. B., Rhee K., Breda A., Zhou N., Dartois V., Jonnala S. R., Via L. E., Mizrahi V., Epemolu O., Stojanovski L., Simeons F., Osuna-Cabello M., Ellis L., MacKenzie C. J., Smith A. R., Davis S. H., Murugesan D., Buchanan K. I., Turner P. A., Huggett M., Zuccotto F., Rebollo-Lopez M. J., Lafuente-Monasterio M. J., Sanz O., Diaz G. S., Lelievre J., Ballell L., Selenski C., Axtman M., Ghidelli-Disse S., Pflaumer H., Bosche M., Drewes G., Freiberg G. M., Kurnick M. D., Srikumaran M., Kempf D. J., Green S. R., Ray P. C., Read K., Wyatt P., Barry 3rd C. E., Boshoff H. I. ACS Infect. Dis. 2017;3:18–33. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya S. K., Gollapalli D. R., Kirubakaran S., Zhang M., Johnson C. R., Benjamin N. N., Hedstrom L., Cuny G. D. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4623–4630. doi: 10.1021/jm900410u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wilson D. J., Xu Y., Aldrich C. C., Felczak K., Sham Y. Y., Pankiewicz K. W. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:4768–4778. doi: 10.1021/jm100424m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandapati K., Gorla S. K., House A. L., McKenney E. S., Zhang M., Rao S. N., Gollapalli D. R., Mann B. J., Goldberg J. B., Cuny G. D., Glomski I. J., Hedstrom L. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;5:846–850. doi: 10.1021/ml500203p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu N. U., Singh V., Ferraris D. M., Rizzi M., Kharkar P. S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;28:1714–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu N. U., Purushothaman G., Thiruvenkatam V., Kharkar P. S. Drug Dev. Res. 2019;80:125–132. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usha V., Gurcha S. S., Lovering A. L., Lloyd A. J., Papaemmanouil A., Reynolds R. C., Besra G. S. Microbiology. 2011;157:290–299. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.042549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorla S. K., Kavitha M., Zhang M., Liu X., Sharling L., Gollapalli D. R., Striepen B., Hedstrom L., Cuny G. D. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:7759–7771. doi: 10.1021/jm3007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers R. E., Buckley G. M., Davies N., Fraser J. L., Galvin F. C., Hannah D. R., Haughan A. F., Jenkins K., Mack S. R., Pitt W. R., Ratcliffe A. J., Richard M. D., Sabin V., Sharpe A., Williams S. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:2539–2542. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers R. E., Buckley G. M., Davies N., Fraser J. L., Galvin F. C., Hannah D. R., Haughan A. F., Jenkins K., Mack S. R., Pitt W. R., Ratcliffe A. J., Richard M. D., Sabin V., Sharpe A., Williams S. C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:2535–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson S. H., Dhar T. G., Ballentine S. K., Shen Z., Barrish J. C., Cheney D., Fleener C. A., Rouleau K. A., Townsend R., Hollenbaugh D. L., Iwanowicz E. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:1273–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jangra S., Purushothaman G., Juvale K., Ravi S., Menon A., Kirubakaran S., Thiruvenkatam V. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019;19:376–382. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190227212334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]