Abstract

We previously reported the serendipitous observation that fenbendazole, a benzimidazole anthelmintic, improved functional and pathological outcomes following thoracic spinal cord contusion injury in mice when administered pre-injury. Fenbendazole is widely used in veterinary medicine. However, it is not approved for human use and it was uncertain if only post-injury administration would offer similar benefits. In the present study we evaluated post-injury administration of a closely related, human anthelmintic drug, flubendazole, using a rat spinal cord contusion injury model. Flubendazole, administered i.p. 5 or 10 mg/kg day, beginning 3 h post-injury and daily thereafter for 2 or 4 weeks, resulted in improved locomotor function after contusion spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with vehicle-treated controls. Histological analysis of spinal cord sections showed that such treatment with flubendazole also reduced lesion volume and improved total tissue sparing, white matter sparing, and gray matter sparing. Flubendazole inhibited the activation of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); suppressed cyclin B1 expression and Bruton tyrosine kinase activation, markers of B cell activation/proliferation and inflammation; and reduced B cell autoimmune response. Together, these results suggest the use of the benzimidazole anthelmintic flubendazole as a potential therapeutic for SCI.

Keywords: b cell-directed therapy, cyclin b1, flubendazole, mild microtubule destabilization, traumatic SCI

Introduction

In a serendipitous finding, it was observed that fenbendazole treatment improved functional and pathological outcomes following spinal cord injury (SCI) in a mouse contusion model.1 Fenbendazole is a benzimidazole anthelmintic used to treat helminth infections such as pinworm. Its primary mechanism is to bind tubulin, disrupting microtubule formation and associated functions including mitosis.2 In contrast to the pseudo-irreversible binding of colchicine to tubulin, benzimidazole anthelmintics bind to mammalian tubulin in a rapidly reversible manner, acting as mild inhibitors of tubulin polymerization.3,4 They do not cause the depolymerization of existing microtubules.

The weak interaction of benzimidazole anthelmintics with mammalian tubulin can disrupt the division of rapidly dividing cells such as lymphocytes, leading to an anti-inflammatory/immunosuppression response.2,5–8 Although initial studies indicated that fenbendazole had minimal effects on the murine immune response,9 more recent findings demonstrate that fenbendazole suppresses B cell activation/proliferation and alters the onset and severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.6,10

Fenbendazole is extensively used in veterinary medicine to treat parasitic infections. However, it is not approved for human use. Another benzimidazole anthelmintic, flubendazole, is approved for human use,11 and can be administered long term with minimal toxicity and side effects at therapeutic doses.12 Flubendazole crosses the blood–brain barrier.13 Based on its antiproliferative properties, flubendazole has been identified in screens for anticancer activity.14–16 In our previous fenbendazole study, mice received the drug pre-injury as an additive to their feed. The goal of the present study was to determine whether post-injury administration of the closely related drug, flubendazole, would improve functional and pathological outcomes using a rat contusional SCI model.

Methods

Animals

Female Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats ∼3 months of age, weighing 200–250 g, were used (Charles River, Indianapolis, IN), without identification of their estrous cycle. Female rats are used because of the need for manual post-injury bladder expression, which is facilitated in females because of their shorter urethra. In a recent study, male and female rats exhibited similar patterns of recovery following experimental SCI.17 In a separate study, the phase of the estrous cycle at the time of contusion injury did not affect outcome.18 Given the neuroprotective effects of estrogen and progesterone and sex differences in many acute injury paradigms it is essential to confirm efficacy in male rats in future study. Rats were kept under standard housing conditions for at least 1 week following arrival in an enclosed, pathogen-free animal facility. All experimental procedures were approved and conducted in accordance with the Guidelines of the United States National Institutes of Health and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Kentucky.

Contusional SCI

SCI was modeled in rats using a moderately severe contusion injury (180 kdyn, T10, Infinite Horizon SCI Impactor).19 The contusive rat thoracic SCI is widely used and produces similar morphological, biochemical, and functional outcomes to those of humans following SCI.20,21 The moderately severe contusion injury (force setting 180 kdyn) results in partial deficits in hindlimb function in rats.19

Flubendazole intraperitoneal (IP) administration

Flubendazole was prepared by dissolving the drug in 0.9% saline plus 0.01% Tween 80.15 Rats were randomly assigned to the following groups (n = 10 per group): (1) contusion-injured rats that received daily IP injections of 5 mg/kg/day of flubendazole for 2 weeks, beginning 3 h post-injury; (2) contusion-injured rats that received daily IP injections of 10 mg/kg/day of flubendazole for 2 weeks, beginning 3 h post-injury; (3) contusion-injured rats that received daily IP injections of 10 mg/kg/day of flubendazole for 4 weeks, beginning 3 h post-injury; (4) contusion-injured rats that received daily IP injections of vehicle (0.9% saline plus 0.01% Tween 80) for 2 weeks, beginning 3 h post-injury; and (5) rats that received sham operation without injury.

The flubendazole dose (5–10 mg/kg/day) for rats used in this study is comparable to the human dose of 100 mg/day commonly prescribed for treating pinwoms (https://drugs.ncats.io/substance/R8M46911LR),15 after factoring in a dose conversion factor from human to rat of 6.2.22,23 Flubendazole has also been shown to provide clinical improvement in patents with neurocysticercosis at a dose of 20 mg/kg, twice a day for 10 days.13

The starting time of intervention, beginning at 3 h post-injury, was chosen as an intermediate time point between acute administration immediately following injury24 and delayed administration of several hours to days post-injury.20,25 The therapeutic window will be further evaluated in future studies. IP administration was chosen because flubendazole is poorly soluble in aqueous systems and has low bioavailability after oral treatment in animals and humans.26–28 The majority of an oral dose (> 80%) is excreted in feces and only very small amounts of unchanged drug (< 0.1%) are found in the urine. The half-life of flubendazole in tissues is 1–2 days. The 2 and 4 week flubendazole treatment durations were chosen to target the time course of proliferation of astrocytes and B cells after contusive SCI in rats.29–34 In mice, B cell proliferation peaks at 14 days and remains elevated at 28 days following contusive SCI.35 However, this is influenced by the site of injury.30,36,37

Antibodies and chemicals

Flubendazole was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-IgG and anti-cyclin B1 antibody were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-GFAP antibody and anti-total BTK antibody were from Novus Biologicals USA (Littleton, CO). Anti-phospho-BTK-Y223 antibody was purchased from ABclonal (Woburn, MA). Anti-CD45RA-PE antibody was purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA). Anti-GAPDH antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Assessment of locomotor function

Open field locomotor function was evaluated pre-injury, immediately and 3 and 7 days post-injury, and then weekly from until 7 weeks post-injury using the Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) rating scale38 as in our previous studies.24,39 Two evaluators, trained and certified by the Ohio State program, participated in the assessment in a blinded manner.

Kinematic analysis

Kinematic analysis provides a detailed analysis of limb, joint movement, and locomotor function. The kinematic analysis is an objective method to assess plantar stepping and coordination based on the Regularity Index (RI%), Coordinated Plantar Stepping Index% (CPI%), and Plantar Stepping Index% (PSI%). Kinematic software (Max Traq, Innovision Systemic, Columbiaville, MI) was utilized to analyze sagittal and ventral view digital video recordings of each rat walking on a platform,40 with a minimum of three passes of each rat per session. Coordinated Plantar Stepping Index, Regularity Index, and Plantar Stepping Index scores were obtained. The rats were trained to walk on the platform pre-operatively, and were evaluated at 7 weeks post-injury.

Spinal cord tissue processing

For Western blot analysis, animals were euthanatized at 4 weeks post-injury by Fatal Plus containing pentobarbital (100 mg/kg for rat, IP injection, n = 3 per group). A 5 mm spinal cord centered on lesion site was removed and snap-frozen on dry ice, then stored at -80°C. For histological staining analysis, at the conclusion of the locomotor assessment, animals were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with cold 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (n = 6 per group). Fixed spinal cord blocks (2 cm in length) centered at the lesion epicenter were immediately dissected, post-fixed in the same fixative solution for 4 h at 4°C, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in phosphate buffered saline at 4 oC, and further processed for frozen/cryostat sections.

Histological staining and analysis

Histological staining and analysis of fixed spinal cord sections was performed as previously described.1,24,39,41 Spinal cords were serially cryosectioned at a thickness of 20 μm. Every fifth section (interval between 100 μm) was mounted onto each Fisherbrand Superfrost Plus slide. The interval between two sections on each slide was 1 mm. Ten sets of slides were collected and stored at -20°C. A modified eriochrome cyanine (EC) staining plus cresyl violet staining protocol for myelin that differentiates both white matter and cell bodies were performed to visualize spared spinal tissue on one set of slides.41 Briefly, the frozen spinal cord sections were thawed, cleared (Hemo-De, Fisher), hydrated, and stained with EC solution (Sigma; 0.2% EC, 0.5% aqueous H2SO4, and 10% FeCl3) at room temperature for 10 min. This was followed by washes in water and differentiation for 1 min in 0.5% aqueous NH4OH. The slides were then counterstained with cresyl violet staining solution.

The reaction was terminated with rinses in water before sections were dehydrated and cover-slipped. Image analysis was performed on each EC-stained section and histological outcomes were evaluated by measuring total spinal section area, gray matter sparing, and lesion area on individual sections using Scion Image System. White matter sparing was calculated by subtracting the lesion area and gray matter area from the total section area. Volume of spared tissue (total tissue sparing, total white matter sparing, or total gray matter sparing) was calculated by summing individual section tissue sparing areas and multiplying the distance between sections as previously described.1,24,39,41 The percentage of total tissue sparing was calculated from 11 evenly spaced sections based on the lesion area divided by the total spinal section area, converted to a percentage, and subtracted from 100%. The lesion volume was calculated by summing individual section lesion area and multiplying the distance between sections.

Western blotting

Spinal cord samples were processed for Western blotting analysis as described in our previous studies.1,39,42 Briefly, the protein samples were obtained by homogenization, sonication, and microcentrifugation of the spinal cord samples in a radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) lysis buffer at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Protein quantities were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method. Samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample) were then loaded on sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels and electrotransfered to nitrocellulose membranes. After transfer, membranes were incubated in 20 mL of blocking buffer (5% powdered milk in 1 x tris buffered saline (TBS), 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times for 10 min with 25 mL of wash buffer (1 x TBS, 0.1% Tween 20). Membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight with one of the primary antibodies (Table 1). Blots were probed with a primary polyclonal antibody against specific targets and re-probed with a monoclonal antibody against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) as a loading control. Blots were then incubated with IRDye® anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:5000). Blots were visualized and analyzed on the Li-Cor Odyssey infrared imaging system (Lincoln, NE).

Table 1.

Primary and Secondary Antibodies

| Antibodies | Molecule Wt. kDa | Source | Dilution | Incubation Time/ Temperature | Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | |||||

| Cyclin B1 (Polyclonal) | 58 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | 18 h/4°C | Abcam |

| GFAP (Monoclonal) | 43–45 | Mouse | 1:200 | 18 h/4°C | Santa Cruz Biotech |

| pBTK (Tyr233, Polyclonal) | 77 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | 18 h/4°C | Cell Signaling Tech |

| Total BTK (Monoclonal) | 77 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | 18 h/4°C | Cell Signaling Tech |

| IgG (Monoclonal) | 50 | Rabbit | 1:500 | 18 h/4°C | Abcam |

| GAPDH | 36 | Rabbit | 1:1000 | 18 h/4°C | Sigma |

| GAPDH | 36 | Mouse | 1:1000 | 18 h/4°C | Sigma |

| Secondary Antibodies | |||||

| IR Dye 800 | Anti-rabbit | 1:5000 | 1h/RT | LI-COR Biosciences | |

| IR Dye 680 | Anti-mouse | 1:5000 | 1h/RT | LI-COR Biosciences | |

RT, room temperature.

Flow cytometry analysis

Sham-operated and injured rats with treatment of flubendazole or vehicle were euthanized at 4 weeks post-injury or sham operation. Spleen samples were collected and processed for measuring the population of splenic CD45RA + B cells using CD45RA Mouse Anti-Rat mAb (Cat# MR6404 CD45RA-PE, Invitrogen) and flow cytometry. Immediately after deep anesthesia, the spleen samples were collected. The spleen samples were removed and minced in a 3.5 cm dish with Hank's Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Invitrogen), then transferred to a 50 mL tube with HBSS. The splenic cell samples were then passed through a 40 μm nylon cell strainer to obtain a single-cell suspension as previously described.43 Red blood cells (RBCs) in the resulting splenic cells were lysed using RBC lysis buffer (eBioscience). After washing, the splenic cell samples were re-suspended in 5 mL of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen). A flow cytometry system (Sony SY3200 [Synergy] Cell Sorter, Sony Biotechnology iCyT, San Jose, CA, using the Core Facility, http://www.research.uky.edu/core/flow/) was used to measure the populations of CD45RA + B cells in the splenic cell samples using antibodies against CD45RA (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The population of activated B cells was automatically calculated as the percentage of specific CD45RA-positive cells (CD45RA, a marker for activated B cells).

Statistical analysis

BBB scores, kinematic data, histological results (lesion volume and tissue sparing data), Western blot measures, and flow cytometry analysis were statistically analyzed using StatView (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were presented as mean ± SEM. Group differences were evaluated by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test (p < 0.05 was considered significant).

Results

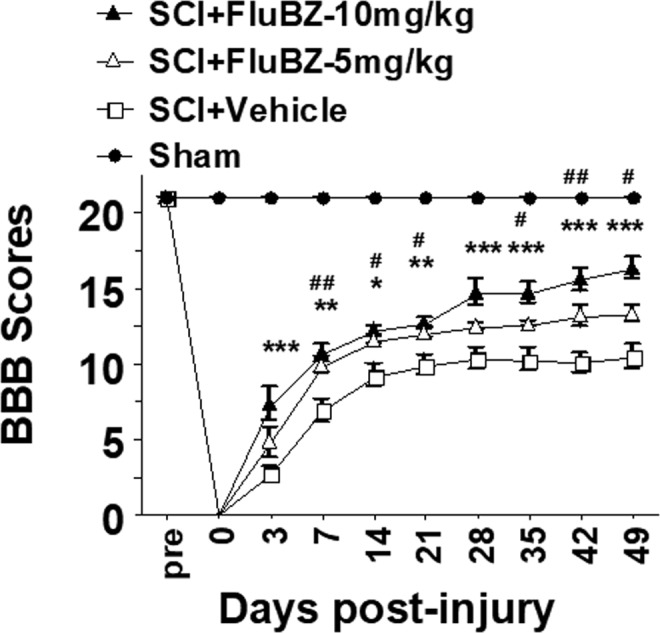

We initially examined two doses of flubendazole, 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, IP administration, with treatment initiated 3 h following injury followed by daily administration for 14 days. This time course was chosen based on the time course of B cell proliferation following SCI.29,35 No significant differences in actual force, displacement, or velocity were found between flubendazole-treated and vehicle-treated groups, indicating similar injuries to all animals (Table 2). Flubendazole treatment was well tolerated and did not result in alterations in body weight, as compared with vehicle-treated animals, following SCI (Table 3). Both the 5 mg/kg/day and 10 mg/kg/day doses resulted in improved outcomes in locomotor performance, although greater improvement was observed with the 10 mg/kg/day dose, which was selected for subsequent studies (Fig. 1). The 5 mg/kg/day and 10 mg/kg/day doses both also resulted in similar reduction in lesion volume and improvement in total tissue sparing, white matter sparing, and gray matter sparing (Figs. 2–5). At the epicenter, only treatment with the high dose of flubendazole (10 mg/kg/day) resulted in a significant increase in the gray matter sparing following contusion injury to the spinal cord (Fig. 5B).

Table 2.

Injury Parameters

| Treatment group | Actual force (kdyn) | Displacement (μm) | Velocity (mm/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCI+FluBZ 10 mg/kg/day | 185.2 ± 1.07 | 848.0 ± 44.6 | 119.7 ± 1.5 |

| SCI+FluBZ 5 mg/kg/day | 183.7 ± 0.91 | 943.2 ± 36.9 | 122.7 ± 0.7 |

| SCI+Vehicle | 183.5 ± 1.2 | 954.0 ± 48.6 | 121.7 ± 1.0 |

Values are mean ± SEM. No significant differences in impact force, displacement, and velocity were found between the treatment groups (n = 10 per group).

SCI, spinal cord injury; FluBZ, flubendazole.

Table 3.

Body Weight of Animals Per Week (g)

| Groups | 1w | 2w | 3w | 4w | 5w | 6w | 7w |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 225.9 ± 3.1 | 234.2 ± 3.5 | 239.6 ± 3.6 | 247.9 ± 4.5 | 254.8 ± 5.4 | 258.1 ± 5.8 | 260.1 ± 5.2 |

| II | 231.8 ± 3.6 | 237.7 ± 3.7 | 246.8 ± 6.2 | 251.5 ± 6.9 | 259.1 ± 6.5 | 262.0 ± 6.8 | 267.0 ± 6.2 |

| III | 232.7 ± 3.5 | 238.4 ± 3.8 | 246.5 ± 4.1 | 251.6 ± 4.9 | 261.9 ± 3.3 | 262.3 ± 3.8 | 266.9 ± 3.5 |

I, spinal cord injury (SCI)+vehicle; II, flubendazole (FluBZ) 5 mg/kg/day; III, SCI+FluBZ 10 mg/kg/day.

Values are mean ± SEM. No significant differences in the body weight of animals per week were found between the vehicle- and flubendazole-treated animals (n = 10 per group).

FIG. 1.

Two-week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) improves locomotor function after spinal cord injury (SCI). Both the 5 mg/kg/day and 10 mg/kg/day doses of 2-week intraperitoneal (IP) treatment with FluBZ resulted in improved locomotor function, measured by Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) scores, up to 49 days after contusive SCI compared with vehicle treated controls Greater improvement was observed with the 10 mg/kg/day dose. Contusive SCI was produced using the Infinite Horizons impactor, 180 kdyn setting, at T10. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001, FluBZ treatment with 10 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01, FluBZ treatment with 5mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment, n = 10 per group.

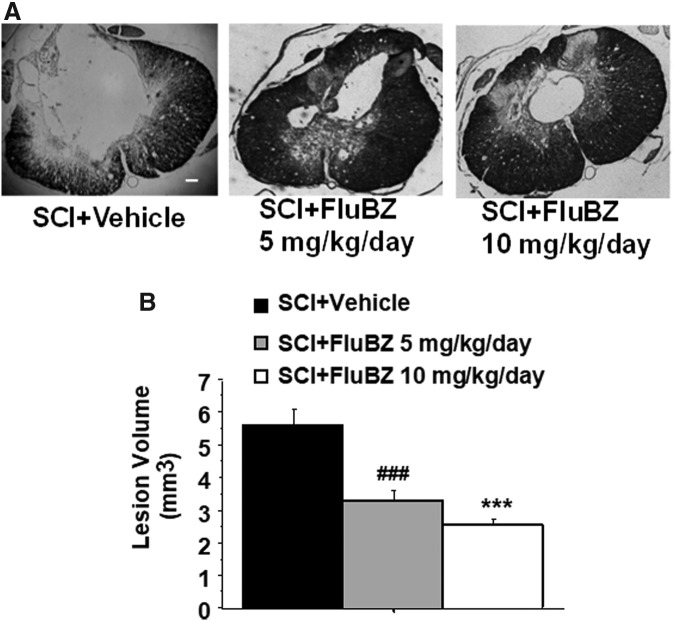

FIG. 2.

Effects of the 2 week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) on lesion volume after spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Photomicrographs of representative transverse spinal cord sections from rats at 49 days after contusive SCI (180 kdyn). The sections were from the lesion epicenter, obtained from a vehicle-treated rat (left), FluBZ (5 mg/kg/day)-treated rat (middle), and FluBZ (10 mg/kg/day)-treated rat (right). The sections were stained with eriochrome cyanine for myelin. Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) FluBZ post-treatment resulted in a significant decrease in lesion volume after contusion injury to the spinal cord Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 1. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, ***p < 0.01 (FluBZ treatment at 10 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment); ###p < 0.001 (FluBZ treatment at 5 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), n = 6/group.

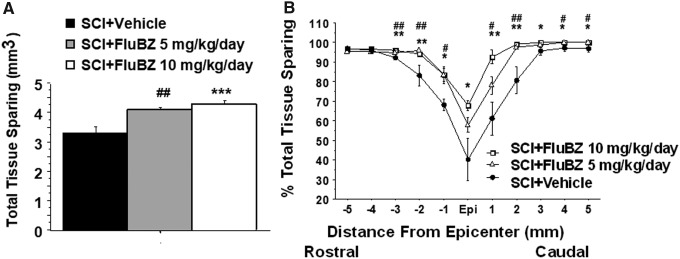

FIG. 3.

Effects of the 2 week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) on total tissue sparing after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) (180 kdyn). Post-injury administration of 2 week treatment with FluBZ resulted in a significant increases in total tissue sparing (A) and tissue sparing at 3–5 mm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter (B) following contusion injury to the spinal cord. Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 1. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (FluBZ treatment at 10 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 (FluBZ treatment at 5 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), n = 6/group.

FIG. 4.

Effects of the 2 week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) on white matter sparing after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) (180 kdyn). Post-injury administration of 2-week treatment with FluBZ resulted in a significant increases in total white matter sparing (A) and white matter sparing at 3–5 mm rostral and caudal to the injury epicenter (B) following contusion injury to the spinal cord. Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 1. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 (FluBZ treatment at 10 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), #p < 0.05, and ##p < 0.01 (FluBZ treatment at 5 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), n = 6/group.

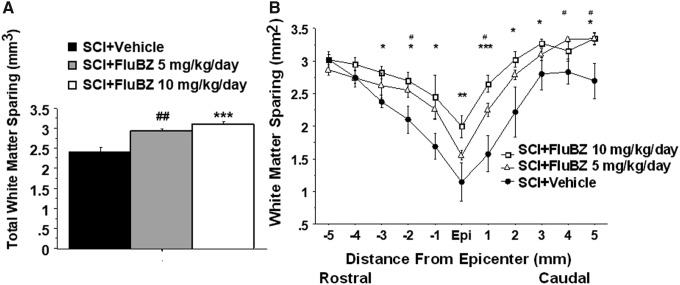

FIG. 5.

Effects of the 2 week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) on gray matter sparing after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) (180 kdyn). Post-injury administration of 2 week treatment with FluBZ resulted in a significant increases in total gray matter sparing (A) and gray matter sparing at injury epicenter (10 mg/kg/day only) and 4 mm caudal to the injury epicenter (B) following contusion injury to the spinal cord. Injury conditions and treatment groups are as described in Figure 1. Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (FluBZ treatment at 10 mg/kg/day vs. vehicle treatment), #p < 0.05, #p < 0.01 (FluBZ treatment at 5 mg/kg/day versus vehicle treatment), n = 6/group.

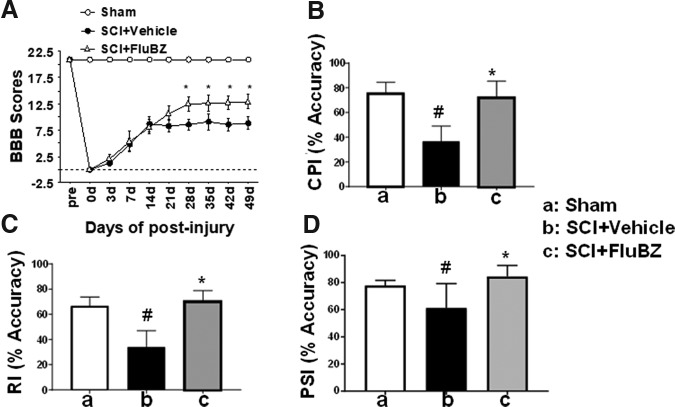

Improvement in open field locomotion with the two drug doses was similar until 21 days post-injury, after which the BBB scores for animals receiving the 5 mg/kg/day dose plateaued whereas those receiving 10 mg/kg/day continued to improve. This suggested that a longer flubendazole treatment duration with the 10 mg/kg/day dose might result in further improvement. A 4 week treatment duration with 10 mg/kg/day flubendazole resulted in improved locomotor recovery compared with the vehicle control in the same study (Fig. 6A), but not compared with the 2 week treatment duration at the same dosage in the earlier study. Locomotor function following the 4 week treatment duration was also evaluated using kinematic analysis. Flubendazole treatment resulted in improvements in coordinated plantar stepping index, regularity index, and plantar stepping index (Fig. 6B–D).

FIG. 6.

Effects of 4 week treatment with flubendazole (FluBZ) on locomotor function after spinal cord injury (SCI). (A) Four-week treatment with FluBZ (10 mg/kg/day) resulted in improved lovomotor function measured by Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan (BBB) scores 7 weeks after contusion SCI in rats, as compared with rats treated with vehicle. (B–D) Kinematic analysis showed that 4 week treatment with FluBZ (10 mg/kg/day) also resulted in significant increases in Coordinated Plantar Stepping Index% (B), Regularity Index% (C), and Plantar Stepping Index% (D) at 7 weeks after contusive SCI compared with vehicle-treated controls (n = 10 per group). Data were presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05, compared with vehicle-treated animals, #p < 0.05, compared with sham group, n = 10/group.

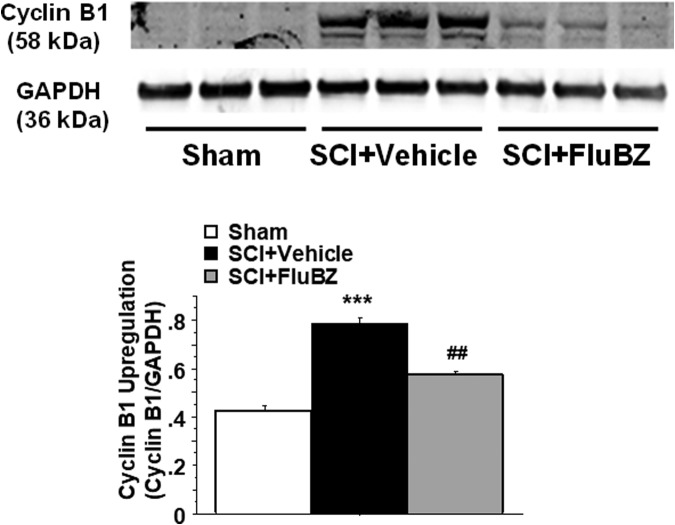

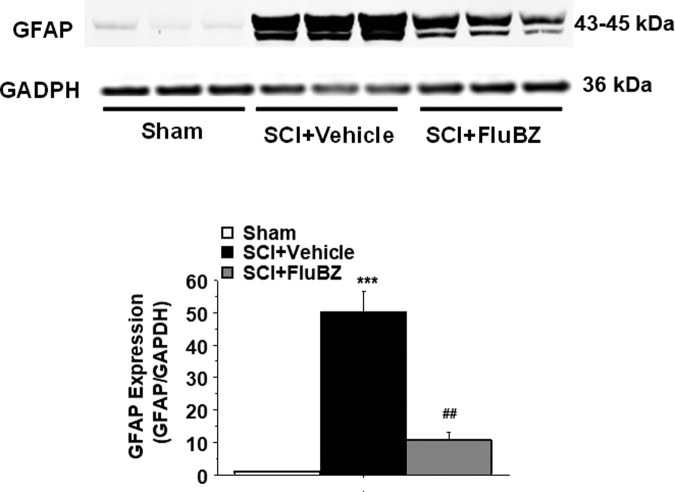

To examine the effects of flubendazole on cell proliferation and hypertrophy, we evaluated levels of cyclin B1 and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the SCI epicenter following 4 weeks of treatment with flubendazole or vehicle. Western blot analysis showed that contusive SCI resulted in significant increases in the levels of cyclin B1 (Fig. 7) and GFAP (Fig. 8) in the injured spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham animals. Flubendazole treatment significantly reduced the injury-induced cyclin B1 (Fig. 7), a key regulator of mitosis, and GFAP upregulation (Fig. 8).

FIG. 7.

Effects of flubendazole (FluBZ) post-treatment on cyclin B1 protein analyzed by quantification of Western blotting data. Western blot analysis of spinal cord samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample) at lesion epicenter showed that contusion injury induced upregulation of cyclin B1 activity in the spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham-operated animals, which was reduced by FluBZ treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks) after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with vehicle-treated animals. Quantification of cyclin B1/ glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) 4 weeks after contusive SCI was performed by the fold of blot density. Antibody was specific for the cyclin B1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group, and analyzed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, ***p < 0.001 compared with sham-operated animals and ##p < 0.01 compared with vehicle-treated SCI animals.

FIG. 8.

Effects of flubendazole (FluBZ) post-treatment on glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) analyzed by quantification of Western blotting data. Western blot analysis of spinal cord samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample) at the lesion epicenter showed that contusion injury increased GFAP activity in the spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham-operated animals. FluBZ treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks) resulted in reduced levels of GFAP in the spinal cord lesion site at 4 weeks after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with vehicle-treated animals. Quantification of GFAP/glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) 4 weeks after contusive SCI was performed by the fold of blot density. Antibody was specific for the GFAP. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group, and analyzed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, ***p < 0.001compared with sham-operated animals and ##p < 0.01 compared with vehicle-treated SCI animals.

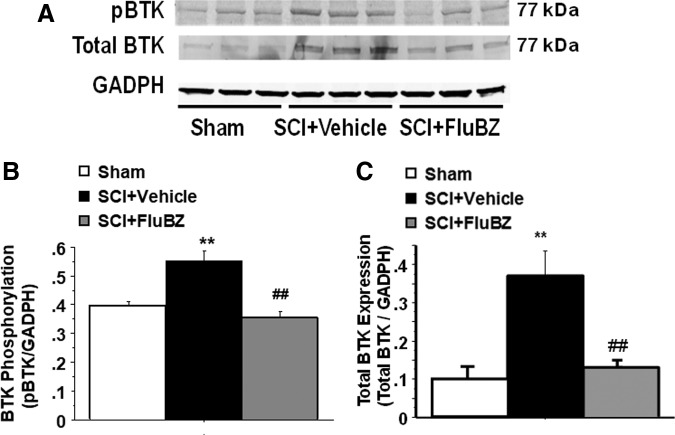

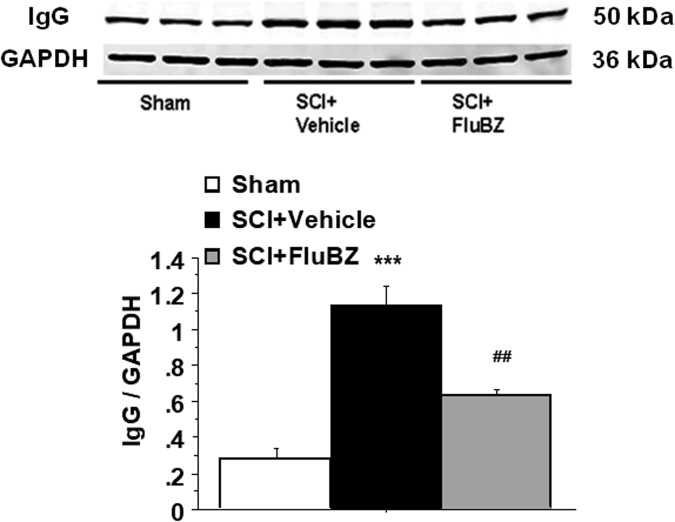

Western blot analysis also revealed significant increases in the levels of Phospho-Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK, Fig. 9A, B), total BTK (Fig. 9A, C), and immunoglobulin (Ig)G (Fig. 10) at the lesion site in the spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham animals. BTK is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase that regulates B-lymphocyte proliferation, development, differentiation, and signaling.44 Flubendazole treatment significantly reduced the injury-induced upregulation of phospho-BTK, total BTK (Fig. 9) and IgG (Fig. 10).

FIG. 9.

Effects of flubendazole (FluBZ) post-treatment on Bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) phosphorylation and total BTK protein analyzed by quantification of Western blotting data. Western blot analysis of spinal cord samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample) at the lesion epicenter showed that contusion injury increased BTK phosphorylation (A and B) and total BTK protein (A and C) in the spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham-operated animals. FluBZ treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks) resulted in reduced levels of BTK phosphorylation (A and B) and total BTK protein (A and C) in the spinal cord lesion site at 4 weeks after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with vehicle-treated animals. Quantification of total BTK/glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) or phospho BTK/GAPDH 4 weeks after contusive SCI was performed by the fold of blot density.Antibodies were specific for the total BTK or BTK phosphorylation (phospho-BTK-Y223).Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group, and analyzed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, **p < 0.001 compared with sham-operated animals and ##p < 0.01 compared with vehicle-treated SCI animals.

FIG. 10.

Effects of flubendazole (FluBZ) post-treatment on levels of total immunoglobulin (Ig)G analyzed by quantification of Western blotting data. Western blot analysis of spinal cord samples (30 μg of protein extract each sample) at the lesion epicenter showed that contusion injury increased total IgG in the spinal cord 4 weeks post-injury compared with sham-operated animals. FluBZ treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks) resulted in reduced levels of total IgG in the spinal cord lesion site at 4 weeks after contusive spinal cord injury (SCI) compared with vehicle-treated animals. Quantification of total IgG/ glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) 4 weeks after contusive SCI was performed by the fold of blot density. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group, and analyzed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc analysis, ***p < 0.001 compared with sham-operated animals and ##p < 0.01 compared with vehicle-treated SCI animals.

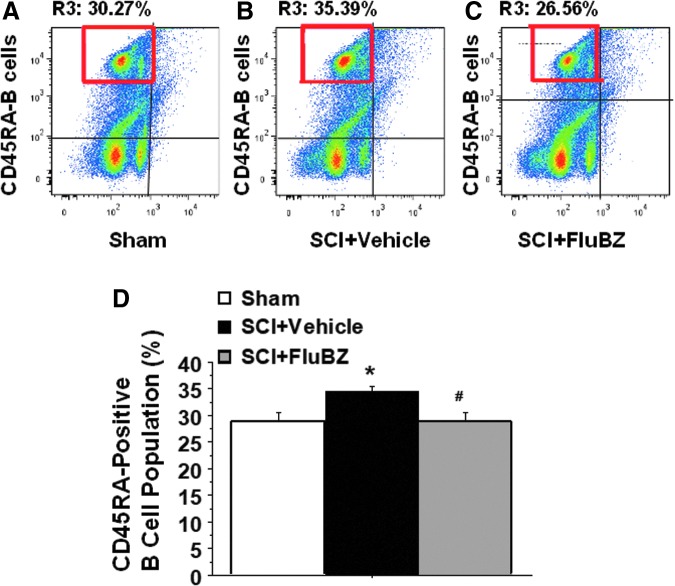

Flow cytometry data demonstrated that a significant elevation in splenic CD45RA-positive B cells was observed in the SCI as compared with the sham group, and was reduced by flubendazole treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks, Fig. 11).

FIG. 11.

Injury-induced upregulation of CD45RA-positive B cell population measured by flow cytometry and blockade by the flubendazole (FluBZ) treatment. Flow cytometry analysis of splenic samples showed that contusion injury caused a significant elevation in CD45RA-positived B cells in the spinal cord injury (SCI)-vehicle (B and D) compared with the sham group (A and D), and this increase was blocked by the FluBZ treatment (10 mg/kg/day, starting at 3 h post-injury for 4 weeks, (C and D). Anti-CD45RA-PE antibody was specific for the rat CD45RA-B cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, n = 3 per group, and analyzed with one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis, *p < 0.05 compared with sham-operated animals and #p < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated SCI animals.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to determine whether post-injury administration of flubendazole would improve functional and pathological outcomes using a rat contusional SCI model and to investigate potential therapeutic mechanisms of its action. Flubendazole, administered IP at 5 and 10 mg/kg/day beginning 3 h following contusive SCI followed by daily administration for 2–4 weeks, resulted in improved locomotor function, increased tissue sparing, and a reduction in markers of cell proliferation (cyclin B1), B cell proliferation, development, differentiation, and signaling (BTK), and inflammation (GFAP) in the injured spinal cord, along with a decreased splenic B cell response.

The rationale for using an anthelmintic to treat SCI is not readily apparent. This was serendipitous, resulting from the treatment of all mice in our facility with fenbendazole following the identification of pinworms.1 Flubendazole was chosen for the present study because of its approved use in humans and very low degree of toxicity at therarpeutic doses.15 Flubendazole inhibits tubulin polymerization by binding to a colchicine-sensitive site that is distinct from that of vinca alkaloids, and acts as a mild inhibitor of tubulin polymerization.2–5,15 The flubendazole inhibits microtubule function through a mechanism distinct from Vinca alkaloids and thereby does not induce neuropathic pain,15 which is dose-limiting toxicity of vinca alkaloid microtubule inhibitors.

Microtubules, and the state of microtubule polymerization, influence many cellular functions, including organelle and vesicular transport, cytokine secretion, and cell division and migration. These functions can be disrupted by both microtubule stabilization (Taxol/Paclitaxel) and destabilization (colchicine, fenbendazole, flubendazole).

Traumatic injury to the spinal cord induces a sustained inflammatory response.45 Chronic inflammation alters tissue remodeling and may contribute to neurodegeneration and locomotor deficits.45,46 Major components of the chronic inflammatory response include sustained reactive astrogliosis and B cell autoimmune neuroinflammation that increase production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines.29,31–33

For targeting inflammation, there is increasing interest in the utilization of tubulin polymerization inhibitors such as colchicine.42,47 By impairing microtubule assembly, colchicine disrupts astroglial activation, microtubule-based inflammatory cell chemotaxis, generation of cytokines and leukotrienes, and phagocytosis.48,49 The mechanism by which colchicine and related drugs exert their anti-inflammatory action is not fully understood, although it includes the inhibition of neutrophil and monocyte accumulation, and also the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokine release.50 Based on its multimodal mechanisms, colchicine is also being investigated for the treatment of other chronic inflammatory conditions.48,51,52 Following traumatic brain injury, colchicine reduces macrophage infiltration as well as the extent of astrogliosis.47,53 However, colchicine has a narrow therapeutic window and exhibits significant toxicity.54,55

As a mild inhibitor of mammalian tubulin polymerization, flubendazole is also hypothesized to inhibit neuroinflammation in the injured spinal cord after SCI.

The present study demonstrated that Flubendazole treatment significantly attenuated the levels of the key astroglial inflammatory and proliferating marker GFAP at the lesion site on the spinal cord 4 weeks after SCI. Reactive astrogliosis is a gradual process after SCI. In the initial stages of astrogliosis, there is aberrant hypertrophy of astrocytes with a slight increase in GFAP levels. Reactive astrogliosis surrounds the lesion site, protects the spread of the injury, and minimizes the extent of the SCI lesion.56 As time elapses, reactive astrocytes show intense GFAP expression, substantial hypertrophy, and significant proliferation.56 This leads to increased production of pro-inflammatory factors including transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, adhesion/recognition molecules, cyclooxygenase 2, and inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase along with chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), disruption of individual territories of astrocytes, tissue distortion and damage, and a glial scar formation at delayed/chronic stages or in severe injury. A key impediment to axon regeneration is the astroglial scarring at the injury site at later time points after SCI.56 In humans, immunohistochemical data have shown the presence of dense astrogliosis at 11 days after injury that was still evident after 1 year post-SCI.56 Therefore, reducing astroglial proliferation, astroglial scarring, and CSPGs at the lesion site is desired to attenuate neuroinflammation and neuronal damage and improve axonal regeneration potential after SCI.

Previously, microtubule stabilization with Taxol was shown to promote axon regeneration and reduce fibrogliotic scarring following SCI.57 A subsequent study confirmed the anti-scarring properties of Taxol, but not the promotion of serotonergic axon growth or neuroprotection.58 Although Taxol stabilizes microtubules in contrast to the microtubule disruption by flubendazole, both actions interfere with mitosis and cell proliferation. Our results suggest that further investigation of flubendazole with respect to its efficacy in the suppression of astrocyte proliferation, astroglial scar formation, CSPGs expression, and production of inflammatory factors, and the enhancement of axonal regeneration is warranted. Because major producers of cytokines are also helper T-cells and macrophages, the effects of flubendazole in the infiltration/migration of these cells into the injury epicenter, the release of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and the removal of debris generated after the injury by microglia/macrophages remain to be further evaluated in the future study.

Flubendazole, fenbendazole, and related compounds have been identified as antiproliferative in cancer screens.16,59–61 Relevant to the decrease in cyclin B1 and GFAP observed in the present study, flubendazole caused cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and suppressed the proliferation of glioma cells in vitro, accompanied by reduced cyclin B1 expression.62 A separate study observed that flubendazole decreased cyclin D1 expression, along with the intermediate filament protein vimentin, in breast cancer cells.14

Proliferation of B cells and production of autoantibodies contribute to neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and resultant locomotor deficits subsequent to traumatic SCI in humans and in animal models.29–32,63,64 The autoantibodies are directed against a wide range of antigens (proteins, gangliosides, nucleic acids) and cause axon and myelin damage as well as astroglial activation/proliferation.29–32,63 Locomotor recovery following SCI is improved and neuropathology is decreased in mice lacking B cells.29 B cell-depleting monoclonal antibodies have been developed for use in hematological malignancies, autoimmune diseases,64 and SCI.32 However, these therapies are associated with severe toxicity/side effects resulting from the compromise of immune system function.64,65 Preferable for SCI would be therapeutic strategies to reduce pathogenic activation of B cells, but not markedly impair the normal immune system. Flow cytometry analysis of splenic samples demonstrated that the injury-induced elevation in the CD45RA-positive B cell population after SCI was reduced by flubendazole. Western blot analysis of spinal cord samples showed that flubendazole also significantly reduced the injury-induced upregulation of phospho-BTK, total BTK, and IgG in the lesion site on the spinal cord at 4 weeks post-injury after contusive SCI in rats compared with vehicle-treated groups. BTK plays an essential role in B cell receptor signaling and B cell autoimmunity.66,67

Together, the present study suggests that inhibiting astroglial inflammatory/proliferative and B cell proliferative BTK signaling is a possible mechanism by which flubendazole partly improves locomotor and tissue sparing. Moreover, the anti-astroglial scarring and anti-B cell proliferative effect of flubendazole treatment can be obtained through inhibiting cyclin B1 expression at the lesion site after SCI.

The precise mechanism by which flubendazole influences cyclin B1 expression remains to be determined. In glioma cells, flubendazole decreased cyclin B1 expression, inhibited cell proliferation, promoted apoptosis, and caused cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase.62 In the MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line, flubendazole also arrested the cell cycle at the G2/M phase, accompanied by increased levels of cyclin B1.68 Other microtubule inhibitors alter cyclin B1 expression, with microtubule disruption leading to cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase and increased cyclin B1 expression followed by cyclin B1 degradation and apoptosis.69–73 Cyclin B1 not only mediates mitotic cell proliferation of B cells, astrocytes, and fibroblasts,74–77 but also triggers post-mitotic neuronal complex I oxidative damage, mitochondrial impairment, and apoptosis under excitotoxic conditions.78 Whether flubendazole reduces cyclin B1-mediated complex I oxidative damage and apoptotic neuronal death after SCI remains to be determined.

Microtubule targeting agents have been used to treat cancers because of their antiproliferative properites,79,80 as well as inflammatory conditions including gout and familial Mediterranean fever, and are in pre-clinical studies for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.81,82

The present study demonstrates that flubendazole administration following SCI improves functional and pathological outcomes, accompanied by a reduction in markers of cell proliferation and inflammation. Together, these results suggest the use of the benzimidazole anthelmintic flubendazole, as well as other microtubule-targeting agents, as potential therapeutics for SCI.

Acknowledgments

This research was support by grants from the Neilsen Foundation, the Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust (KSCHIRT) # 11-19A, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) UL1TR000117. We thank Khalid Eldahan for expert assistance with kinematic analysis.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Yu C.G., Singh R., Crowdus C., Raza K., Kincer J., and Geddes J.W. (2014). Fenbendazole improves pathological and functional recovery following traumatic spinal cord injury. Neuroscience 256, 163–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedman P.A. and Platzer E.G. (1978). Interaction of anthelmintic benzimidazoles and benzimidazole derivatives with bovine brain tubulin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 544, 605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lacey E. (1990). Mode of action of benzimidazoles. Parasitol. Today 6, 112–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. MacDonald L.M. (2003). Characterisation of the Benzimidazole-Binding Site on the Cytoskeletal Protein Tubulin. Mudoch University: Perth, Australia [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friedman P.A., and Platzer E.G. (1980). Interaction of anthelmintic benzimidazoles with Ascaris suum embryonic tubulin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 630, 271–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Landin A.M., Frasca D., Zaias J., Van der Put E., Riley R.L., Altman N.H., and Blomberg B.B. (2009). Effects of fenbendazole on the murine humoral immune system. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 48, 251–257 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cabaj W., Stankiewicz M., Jonas W.E., and Moore L.G. (1994). Fenbendazole and its effect on the immune system of the sheep. N. Z. Vet. J. 42, 216–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sajid M.S., Iqbal Z., Muhammad G., and Iqbal M.U. (2006). Immunomodulatory effect of various anti-parasitics: a review. Parasitology 132, 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villar D., Cray C., Zaias J., and Altman N.H. (2007). Biologic effects of fenbendazole in rats and mice: a review. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 46, 8–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ramp A.A., Hall C., and Orian J.M. (2010). Strain-related effects of fenbendazole treatment on murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Lab. Anim. 44, 271–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gottschall D.W., Theodorides V.J., and Wang R. (1990). The metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics. Parasitol. Today 6, 115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kohler P. (2001). The biochemical basis of anthelmintic action and resistance. Int. J. Parasitol. 31, 336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tellez-Giron E., Ramos M.C., Dufour L., Montante M., Tellez E., Jr., Rodriguez J., Gomez Mendez F., and Mireles E. (1984). Treatment of neurocysticercosis with flubendazole. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 33, 627–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou Z.J., Luo X., Zhang W., Peng F., Cui B., Wu S.J., Zheng F.M., Xu J., L.Z. Xu L.Z., Long Z.J., Wang X.T., Li G.H., Wan X.Y., Yang Y.L., and Liu Q. (2015). Flubendazole, FDA-approved anthelmintic, targets breast cancer stem-like cells. Oncotarget 6, 6326–6340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spagnuolo P.A., Hu J., Hurren R., Wang X., Gronda M., Sukhai M.A., Di Meo A., Boss J., Ashali I., Beheshti Zavareh R., Fine N., Simpson C.D., Sharmeen S., Rottapel R., and Schimmer A.D. (2010). The antihelmintic flubendazole inhibits microtubule function through a mechanism distinct from Vinca alkaloids and displays preclinical activity in leukemia and myeloma. Blood 115, 4824–4833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kralova V., Hanusova V., Stankova P., Knoppova K., Canova K., and Skalova L. (2013). Antiproliferative effect of benzimidazole anthelmintics albendazole, ricobendazole, and flubendazole in intestinal cancer cell lines. Anticancer Drugs 24, 911–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walker C., Fry C.M.E., Wang J., Du X., Zuzzio K., Liu N.K., Walker M., and Xu X.M. (2018). Functional and histological gender comparison of age-matched rats after moderate thoracic contusive spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma [Epub ahead of print; DOI: 10.1089/neu.2018.6233] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baker K.A., and Hagg T.J. (2005). An adult rat spinal cord contusion model of sensory axon degeneration: the estrus cycle or a preconditioning lesion do not affect outcome. J. Neurotrauma 22, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scheff S.W., Rabchevsky A.G., Fugaccia I., Main J.A., and Lumpp J.E., Jr. (2003). Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J. Neurotrauma 20, 179–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwon B.K., Okon E.B., Tsai E., Beattie M.S., Bresnahan J.C., Magnuson D.K., Reier P.J., McTigue D.M., Popovich P.G., Blight A.R., Oudega M., Guest J.D., Weaver L.C., Fehlings M.G., and Tetzlaff W. (2011). A grading system to evaluate objectively the strength of pre-clinical data of acute neuroprotective therapies for clinical translation in spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma, 28, 1525–1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Metz G.A., Curt A., van de Meent H., Klusman I., Schwab M.E., and Dietz V. (2000). Validation of the weight-drop contusion model in rats: a comparative study of human spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma, 17, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shin J.W., Seol I.C., and Son C.G. (2010). Interpretation of animal dose and human equivalent dose for drug development. J. Korean Oriental Med. 31, 1–7 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nair A.B., and Jacob S. (2016). A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 7, 27–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yu C.G., and Geddes J.W. (2007). Sustained calpain inhibition improves locomotor function and tissue sparing following contusive spinal cord injury. Neurochem. Res. 32, 2046–2053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wu Y.C., Satkunendrarajah K., Teng Y., Diana S.-L. Chow D.S.L., Buttigieg J., and Fehlings M.G. (2013). Delayed post-injury administration of riluzole is neuroprotective in a preclinical rodent model of cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 30, 441–452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Canova K., Rozkydalova L., and Rudolf E. (2017). Anthelmintic flubendazole and its potential use in anticancer therapy. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 60, 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ceballos L., Mackenzie C., Geary T., Alvarez L., and Lanusse C. (2014). Exploring the potential of flubendazole in filariasis control: evaluation of the systemic exposure for different pharmaceutical preparations. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8, e2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ceballos L., Alvarez L., Mackenzie C., Geary T., and Lanusse C. (2015). Pharmacokinetic comparison of different flubendazole formulations in pigs: A further contribution to its development as a macrofilaricide molecule. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 5(3), 178–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ankeny D.P., Guan Z., and Popovich P.G. (2009). B cells produce pathogenic antibodies and impair recovery after spinal cord injury in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2990–2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ankeny D.P., and Popovich P.G. (2010). B cells and autoantibodies: complex roles in CNS injury. Trends Immunol. 31, 332–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ulndreaj A., Tzekou A., Mothe A.J., Siddiqui A.M., Dragas R., Tator C.H., Torlakovic E.E., and Fehlings M.G. (2017). Characterization of the antibody response after cervical spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma 34, 1209–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casili G., Impellizzeri D., Cordaro M., Esposito E., and Cuzzocrea S. (2016). B-Cell depletion with CD20 antibodies as new approach in the treatment of inflammatory and immunological events associated with spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics 13, 880–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. David S., Zarruk J.G., and Ghasemlou N. (2012). Inflammatory pathways in spinal cord injury. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 106, 127–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu J., Pajoohesh-Ganji A., Stoica B.A., Dinizo M., Guanciale K., and Faden A.I. (2012). Delayed expression of cell cycle proteins contributes to astroglial scar formation and chronic inflammation after rat spinal cord contusion. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ankeny D.P., Lucin K.M., Sanders V.M., McGaughy V.M., and Popovich P.G. (2006). Spinal cord injury triggers systemic autoimmunity: evidence for chronic B lymphocyte activation and lupus-like autoantibody synthesis. J. Neurochem. 99, 1073–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Michiels M., Hendriks R., Heykants J., and van den Bossche H. (1982). The pharmacokinetics of mebendazole and flubendazole in animals and man. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 256, 180–191 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Krízová V., Nobilis M., Prusková L., Chládek J., Szotáková B., Cvilink V., Skálová L., and Lamka J. (2009). Pharmacokinetics of flubendazole and its metabolites in lambs and adult sheep (Ovis aries). J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 32, 606–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Basso D.M., Beattie M.S., and Bresnahan J.C. (1996). Graded histological and locomotor outcomes after spinal cord contusion using the NYU weight-drop device versus transection. Exp. Neurol. 139, 244–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yu C.G., Yezierski R.P., Joshi A., Raza K., Li Y., and Geddes J.W. (2010). Involvement of ERK2 in traumatic spinal cord injury. J. Neurochem. 113, 131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuerzi J., Brown E.H., Shum-Siu A., Siu A., Burke D., Morehouse J., Smith R.R., and Magnuson D.S. (2010). Task-specificity vs. ceiling effect: step-training in shallow water after spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 224, 178–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rabchevsky A.G., Fugaccia I., Sullivan P.G., and Scheff S.W. (2001). Cyclosporin A treatment following spinal cord injury to the rat: behavioral effects and sterological assessment of tissue sparing. J. Neurotrauma 18, 513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu C.G., and Yezierski R.P. (2005). Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling cascade by excitotoxic spinal cord injury. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 138, 244–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guerrero A.R., Uchida K., Nakajima H., Watanabe S., Nakamura M., Johnson W.E., and Baba H. (2012). Blockade of interleukin-6 signaling inhibits the classic pathway and promotes an alternative pathway of macrophage activation after spinal cord injury in mice. J. Neuroinflammation 9, 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mohamed A.J., Yu L., Backesjo C.M., Vargas L., Faryal R., Aints A., Christensson B., Berglof A., Vihinen M., Nore B.F., and Smith C.I. (2009). Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk): function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol. Rev. 228, 58–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bowes A.L., and Yip P.K. (2014). Modulating inflammatory cell responses to spinal cord injury: all in good time. J. Neurotrauma 31, 1753–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nathan C., and Ding A. (2010). Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 140, 871–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leung Y.Y., Yao Hui L.L., and Kraus V.B. (2015). Colchicine—Update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 45, 341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dalbeth N., Lauterio T.J., and Wolfe H.R. (2014). Mechanism of action of colchicine in the treatment of gout. Clin. Ther. 36,1465–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Akira S., Misawa T., Satoh T., and Saitoh T. (2013). Macrophages control innate inflammation. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 15, Suppl. 3, 10–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cocco G., Chu D.C., and Pandolfi S. (2010). Colchicine in clinical medicine. A guide for internists. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 21, 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Martinez G.J., Robertson S., Barraclough J., Xia Q., Mallat Z., Bursill C., Celermajer D.S., and Patel S. (2015). Colchicine acutely suppresses local cardiac production of inflammatory cytokines in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e002128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Khan R., Spagnoli V., Tardif J.C., and L'Allier P.L. (2015). Novel anti-inflammatory therapies for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 240, 497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Giulian D., Chen J., Ingeman J.E., George J.K., and Noponen M. (1989). The role of mononuclear phagocytes in wound healing after traumatic injury to adult mammalian brain. J. Neurosci. 9, 4416–4429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jayaprakash V., Ansell G., and Galler D. (2007). Colchicine overdose: the devil is in the detail. N. Z. Med. J. 120, U2402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zughaier S., Karna P., Stephens D., and Aneja R. (2010). Potent anti-inflammatory activity of novel microtubule-modulating brominated noscapine analogs. PLoS One 5, e9165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Soheila K.A., and Billakanti R. (2012). Reactive astrogliosis after spinal cord injury—beneficial and detrimental effects. Mol. Neurobiol. 46, 251–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hellal F., Hurtado A., Ruschel J., Flynn K.C., Laskowski C.J., Umlauf M., Kapitein L.C., Strikis D., Lemmon V., Bixby J., Hoogenraad C.C., and Bradke F. (2011). Microtubule stabilization reduces scarring and causes axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. Science 331, 928–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Popovich P.G., Tovar C.A., Lemeshow S., Yin Q., and Jakeman L.B. (2014). Independent evaluation of the anatomical and behavioral effects of Taxol in rat models of spinal cord injury. Exp. Neurol. 261, 97–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Michaelis M., Agha B., Rothweiler F., Loschmann N., Voges Y., Mittelbronn M., Starzetz T., Harter P.N., Abhari B.A., Fulda S., Westermann F., Riecken K., Spek S., Langer K., Wiese M., Dirks W.G., Zehner R., Cinatl J., Wass M.N., and Cinatl J., Jr. (2015). Identification of flubendazole as potential anti-neuroblastoma compound in a large cell line screen. Sci. Rep. 5, 8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Duan Q., Liu Y., and Rockwell S. (2013). Fenbendazole as a potential anticancer drug. Anticancer Res. 33, 355–62 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Canova K., Rozkydalova L., and Rudolf E. (2017). Anthelmintic flubendazole and its potential use in anticancer therapy. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 60, 5–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhou X., Liu J., Zhang J., Wei Y., and Li H. (2018). Flubendazole inhibits glioma proliferation by G2/M cell cycle arrest and pro-apoptosis. Cell Death Discov. 4, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dekaban G.A., and Thawer S. (2009). Pathogenic antibodies are active participants in spinal cord injury. J Clin Invest. 119, 2881–2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dorner T., Kinnman N., and Tak P.P. (2010). Targeting B cells in immune-mediated inflammatory disease: a comprehensive review of mechanisms of action and identification of biomarkers. Pharmacol. Ther. 125, 464–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Levesque M.C. and St Clair E.W. (2008). B cell-directed therapies for autoimmune disease and correlates of disease response and relapse. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 121, 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Honigberg L.A., Smith A.M., Sirisawad M., Verner E., Loury D., Chang B., Li S., Pan Z., Thamm D.H., Miller R.A., and Buggy J.J. (2010). The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 13,075–13,080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tucker D.L., and Rule S.A. (2015). A critical appraisal of ibrutinib in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 11, 979–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hou Z.J., Luo X., Zhang W., Peng F., Cui B., Wu S.J., Zheng F.M., Xu J., Xu L.Z., Long Z.J., Wang X.T., Li G.H., Wan X.Y., Yang Y.L., and Liu Q. (2015). Flubendazole, FDA-approved anthelmintic, targets breast cancer stem-like cells. Oncotarget 6, 6326–6340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Xu J., Zuo D., Qi H., Shen Q., Bai Z., Han M., Li Z., Zhang W., and Wu Y. (2016). 2-Methoxy-5((3,4,5-trimethosyphenyl)seleninyl) phenol (SQ0814061), a novel microtubule inhibitor, evokes G2/M cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 78, 308–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang X., Zhao J., Gao X., Pei D., and Gao C. (2017). Anthelmintic drug albendazole arrests human gastric cancer cells at the mitotic phase and induces apoptosis. Exp. Ther. Med. 13, 595–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 71. Řehulka J., Annadurai N., Frydrych I., Znojek P., Džubák P., Northcote P., Miller J.H., Hajdúch M., and Das V. (2017). Cellular effects of the microtubule-targeting agent peloruside A in hypoxia-conditioned colorectal carcinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 861, 1833–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Takahashi K., Ishii K., and Yamashita M. (2018). Staufen1, Kinesin1 and microtubule function in cyclin B1 mRNA transport to the animal polar cytoplasm of zebrafish oocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503, 2778–2783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Nakamura N., Tokumoto T., Ueno S., and Iwao Y. (2005). The cytoskeleton-dependent localization of cdc2/cyclin B in blastomere cortex during Xenopus embryonic cell cycle. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 72, 336–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ramenzoni L.L., Weber F.E., Attin T., and Schmidlin P.R. (2017). Cerium chloride application promotes wound healing and cell proliferation in human foreskin fibroblasts. Materials (Basel) 10(6), 573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kim K.C., Oh W.J., Ko K.H., Shin C.Y., and Wells D.G. (2011). Cyclin B1 expression regulated by cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 31, 12,118–12,128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wu J., Stoica B.A., and Faden A.I. (2011). Cell cycle activation and spinal cord injury. Neurotherapeutics 8, 221–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Bernasconi M., Ueda S., Krukowski P., Bornhauser B.C., Ladell K., Dorner M., Sigrist J.A., Campidelli C., Aslandogmus R., Alessi D., Berger C., Pileri S.A., Speck R.F., and Nadal D. (2013). Early gene expression changes by Epstein-Barr virus infection of B-cells indicate CDKs and survivin as therapeutic targets for post-transplant lymphoproliferative diseases. Int. J. Cancer 133, 2341–2350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Veas-Pérez de Tudela M., Delgado-Esteban M., Maestre C., Bobo-Jiménez V., Jiménez-Blasco D., Vecino R., Bolaños J.P., and Almeida A. (2015). Regulation of Bcl-xL-ATP synthase interaction by mitochondrial cyclin B1-cyclin-dependent kinase-1 determines neuronal survival. J. Neurosci. 35, 9287–9301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhou J., and Giannakakou P. (2005). Targeting microtubules for cancer chemotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 5, 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Jordan M.A., Wilson L. (2004). Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 253–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ballatore C., Brunden K.R., Huryn D.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M., and Smith A.B. (2012). Microtubule stabilizing agents as potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease and related neurodegenerative tauopathies. J. Med. Chem. 55, 8979–8996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Floria S., and Mitchison T.J. (2016). Anti-microtubule drugs. Methods Mol. Biol. 1413, 403–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]