Abstract

Background

Osteosarcoma is aggressive and prognostic biomarkers are important to predict the outcomes of surgery and chemotherapy. Here, we investigated the potential of transferrin receptor-1 (TfR1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) as prognostic markers of osteosarcoma.

Methods

TfR1 and VEGF in osteosarcoma samples from a cohort of 53 osteosarcoma patients were detected by immunohistochemistry analysis. The correlation of TfR1 and VEGF levels with clinicopathological parameters was analyzed by Pearson chi-square and Spearman-rho tests. Overall patient survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

We found that TfR1 and VEGF expression levels were low in 20.8% and 18.9%; modest in 35.8% and 35.8%; and high in 43.4% and 45.3% of osteosarcoma patients, respectively. TfR1 and VEGF expression was significantly correlated to histologic grade, Enneking stage, and distant metastasis. TfR1 expression was significantly correlated to VEGF expression and both TfR1 expression and VEGF expression were correlated to shorter overall survival.

Conclusions

TfR1 and VEGF are potential prognostic factors for osteosarcoma.

Keywords: Transferrin receptor-1, VEGF, Prognosis, Osteosarcoma

Background

Primary bone tumors are uncommon and the incidence is low [1]. Osteosarcoma (OS) is a pleomorphic sarcoma of the bone in children and adult, and OS patients frequently develop metastasis [2]. With the recent development of adjuvant chemotherapy, the 5-year-free survival rate has improved to approximately 50% for patient with high-grade OS [3, 4]. The identification of new prognostic biomarkers in osteosarcoma has become increasingly important to predict the responsiveness of treatment [5].

Iron is an element essential to cellular activities such as DNA synthesis and cell proliferation [6–8]. Proteins involved in iron metabolism have been shown to promote lung cancer [9–11]. Recent studies have shown high expression of transferrin receptor-1 (TfR1) in a variety of tumors including lung, breast, and bladder cancer as well as malignant glioma, but the clinical significance of TfR1 in tumor remains to be confirmed [12, 13].

Angiogenesis plays an important role in tumor development. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is known to promote neovascularization [14, 15]. Up to now, the association between TfR1 and VEGF expression and the prognosis of OS patients remains unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to examine TfR1 and VEGF expression in OS patients and analyze their prognostic significance for clinical outcomes of OS.

Methods

Subjects

Ethics Committees of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (also named as Tumor Hospital of Hebei Province) approved this study and all patients signed written informed consent. This study enrolled 53 OS patients from 2002 to 2010 from the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, who had not received radiotherapy or chemotherapy. All patient data and follow-up information were collected, including the gender, age, tumor size, histological grade, Enneking stage, and distant metastasis.

Immunohistochemistry analysis

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis was performed on OS tissues using antibodies for TfR1 (1:100; Biogot Tech) and VEGF (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), following a previously described protocol [16]. The results of IHC were judged using the following score system based on the percentage of stained cells, < 1% (0); 1–25% (1); 25–50% (2); 51–80% (3); and > 80% (4); and the intensity of staining, no staining (0); weak staining (1); strong staining (2); and very strong staining (3). The final score was the product of staining intensity and percentage and judged as low (0–3 points), mild (4–7 points), and high (> 7 points).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by using SPSS software 25.0. The association of clinical variables was analyzed by the Pearson chi-square test or Spearman-rho test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed by using the Cox proportional hazard model. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Association of TfR1 and VEGF with clinicopathological parameters

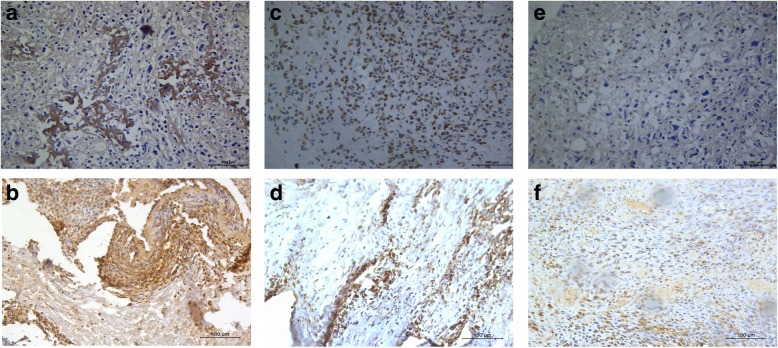

Typical staining of TfR1 and VEGF in OS tissues was presented in Fig. 1. TfR1 expression was low in 20.8%, mild in 35.8% and high in 43.4% of OS tissues, whereas VEGF expression was low in 18.9%, mild in 35.8%, and high in 45.3% of OS tissues. As shown in Table 1, TfR1 and VEGF expression was significantly associated with histological grade, Enneking stage and distant metastasis (all P < 0.05). In addition, TfR1 and VEGF expression showed a significantly positive correlation (P < 0.01, Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Representative immunohistochemical staining of TfR1 and VEGF. a High expression of TfR1 in OS. c Moderate expression of TfR1 in OS. e Low expression of TfR1 in OS. b High expression of VEGF in OS. d Moderate expression of VEGF in OS. f Low expression of VEGF in OS. The cells with positive expression were stained brown

Table 1.

Clinicopathological variables and the expression of TfR1 and VEGF

| TfR1 | P | VEGF | P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low(%) | Mild(%) | High(%) | Low(%) | Mild(%) | High(%) | |||||

| Sex | Female | 25 | 3(12.0) | 10(40.0) | 12(48.0) | 0.332 | 5(20.0) | 11(44.0) | 9(36.0) | 0.405 |

| Male | 28 | 8(28.6) | 9(32.1) | 11(39.3) | 5(17.8) | 8(28.6) | 15(53.6) | |||

| Age | ≥ 20 years | 18 | 4(22.2) | 4(22.2) | 10(55.6) | 0.306 | 3(16.7) | 9(50.0) | 6(33.3) | 0.293 |

| < 20 years | 35 | 7(20.0) | 15(42.9) | 13(37.1) | 7(20.0) | 10(28.6) | 18(51.4) | |||

| Tumor size | < 5 cm | 27 | 6(22.2) | 10(37.0) | 11(40.8) | 0.919 | 6(22.2) | 10(37.0) | 11(40.7) | 0.741 |

| ≥ 5 cm | 26 | 5(19.2) | 9(34.6) | 12(46.2) | 4(15.4) | 9(34.6) | 13(50.0) | |||

| Histologic grade* | I | 15 | 4(26.7) | 8(53.3) | 3(20.0) | 0.04 | 4(26.7) | 9(60.0) | 2(13.3) | 0.02 |

| II | 25 | 5(20.0) | 10(40.0) | 10(40.0) | 5(20.0) | 8(32.0) | 12(48.0) | |||

| III | 13 | 2(15.4) | 1(7.7) | 10(76.9) | 1(7.7) | 2(15.4) | 10(76.9) | |||

| Distant metastasis* | Yes | 23 | 1(4.2) | 11(47.8) | 11(47.8) | 0.029 | 1(4.4) | 13(56.5) | 9(39.1) | 0.008 |

| No | 30 | 10(33.3) | 8(26.7) | 12(40.0) | 9(30.0) | 6(20.0) | 15(50.0) | |||

| Enneking staging* | I | 12 | 8 (66.7) | 3 (25.0) | 7(36.9) | < 0.001 | 6(50.0) | 4(33.3) | 2(16.7) | 0.004 |

| II | 19 | 2 (10.5) | 10(52.6) | 21(43.8%) | 2(10.5) | 10(52.6) | 7(36.9) | |||

| III | 22 | 1 (4.5) | 6 (27.3) | 15 (68.2) | 2(9.1) | 5(22.7) | 15(68.2) | |||

Pearson’s chi-squared test was used. *P < 0.05

Table 2.

The correlation of TfR1 and VEGF expression

| Characteristics | TfR1 | P (Spearman) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low(%) | Mild(%) | High(%) | ||||

| VEGF* | Low | 10 | 6(11.3) | 3(5.7) | 1(1.9) | = 0.001 |

| Mild | 19 | 2(3.7) | 10(18.9) | 7(13.2) | ||

| High | 24 | 3(5.7) | 6(11.3) | 15(28.3) | ||

| 53 | 11 | 19 | 23 | |||

Spearman-rho test was used. *P < 0.05

TfR1 and VEGF were correlated with poor overall survival of OS patients

Table 3 showed the results of univariate Cox hazard analysis of overall survival of OS patients. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that the gender, age, tumor size, and histologic grade had no significance in predicting overall survival, but Enneking staging and distant metastasis predicted a poor overall survival (Fig. 2). Moreover, TfR1 and VEGF were significantly correlated with poor overall survival (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Clinicopathological factors associated with overall survival based on univariate Cox proportional regression analysis

| Characteristics | Overall survival | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | ||||

| Sex | Female | 25 | 1 | 0.837 | |

| Male | 28 | 1.064 | 0.590–1.919 | ||

| Age | ≥ 20 years | 18 | 1 | 0.777 | |

| < 20 years | 35 | 1.093 | 0.591–2.022 | ||

| Tumor size | < 5 cm | 27 | 1 | 0.940 | |

| ≥ 5 cm | 26 | 1.024 | 0.556–1.884 | ||

| Histologic grade* | I | 15 | 1 | 0.412 | |

| II | 25 | 1.267 | 0.634–2.534 | 0.503 | |

| III | 13 | 1.738 | 0.771–3.917 | 0.183 | |

| Distant metastasis* | Yes | 23 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| No | 30 | 0.161 | 0.073–0.356 | ||

| Enneking staging* | I | 12 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| II | 19 | 8.605 | 2.942–25.169 | ||

| III | 22 | 26.039 | 7.679–88.293 | ||

| TfR1* | Low | 11 | 1 | < 0.001 | |

| Moderate | 19 | 0.158 | 0.063–0.398 | ||

| High | 23 | 0.300 | 0.143–0.629 | ||

| VEGF* | Low | 10 | 1 | 0.021 | |

| Moderate | 19 | 0.114 | 0.043–0.303 | ||

| High | 24 | 0.422 | 0.202–0.880 | ||

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. *P < 0.05

Fig. 2.

Overall survival curves of patients with OS. a Association of overall survival with distant metastasis. b Association of overall survival with TfR1 expression. c Association of overall survival with VEGF expression. d Association of overall survival with clinical stage

TfR1 and VEGF are prognostic factors for OS patients

Table 4 showed the results of multivariate Cox hazard analysis of univariate factors listed in Table 3. Enneking staging, TfR1 expression, and VEGF expression were identified as independent prognostic factors of OS patients. Higher TfR1 and VEGF expression, higher Enneking staging, and distance metastasis were associated with significantly higher mortality risk (Plogrank < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Clinicopathological factors associated with overall survival based on multivariate Cox regression analysis

| Overall survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Enneking stage | 4.622 | 2.541–8.406 | < 0.001 |

| TfR1 | 2.514 | 1.445–4.372 | 0.001 |

| VEGF | 2.882 | 1.203–8.217 | 0.002 |

HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. *P < 0.05

Discussion

As a common malignant bone tumor, OS accounts for 30% of all bone malignancies and 3–4% of pediatric tumors [17]. OS has been reported to be the third most common cancer in adolescence [18]. Therefore, it is important to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for OS.

Abnormal iron metabolism is associated with tumorigenesis [19–21]. Iron homeostasis is maintained by the balance of iron uptake, usage, and storage [22]. TfR1 is the main protein responsible for iron absorption. Strong immunohistochemical staining of TfR1 could indicate high cancer cell proliferation and poor prognosis of cancer patients [23–25]. Tumor cells with high TfR1 expression exhibited a high rate of iron absorption and cell proliferation [26].

To our knowledge, our study was the first to report high expression of TfR1 and VEGF in OS tissues. Moreover, we found that high TfR1 and VEGF expression was significantly correlated to histological grade, Enneking staging, and distant metastasis. Furthermore, high TfR1 and VEGF expression was significantly correlated to poor overall survival, and both TfR1 and VEGF were independent prognostic indicators of OS patients.

Our study has several limitations. First, immunohistochemistry analysis is only semi-quantitative, and bias may affect the evaluation of staining score although we analyzed all samples in a blind manner. Second, our sample size is limited. Third, our study is a single-center study.

Conclusions

In summary, TfR1 and VEGF expression is high in OS tissues and is correlated to malignancy grade of OS patients. TfR1 and VEGF are potential prognostic factors of OS patients.

Acknowledgements

N/A

Abbreviations

- OS

Osteosarcoma

- TfR1

Transferrin receptor-1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors’ contributions

HF designed the study. JZ, RD, and JX collected the samples and performed the analysis. HW performed the statistical analysis. All authors wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

N/A

Availability of data and materials

All data and material are available upon request

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics Committees of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University approved this study and all patients signed written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Yes

Competing interests

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hongzeng Wu, Email: ningzhang0311@126.com.

Jinming Zhang, Email: zhangjinming0311@126.com.

Ruoheng Dai, Email: 741842532@qq.com.

Jianfa Xu, Email: 13722988082@163.com.

Helin Feng, Email: fenghelin0311@126.com.

References

- 1.Franchi A. Epidemiology and classification of bone tumors. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2012;9(2):92–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, Juergens H. Osteosarcoma treatment—where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(4):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friebele JC, Peck J, Pan X, Abdel-Rasoul M, Mayerson JL. Osteosarcoma: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44(12):547–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrascu JM, Vermesan D, Mioc ML, Lazureanu V, Florescu S, Tarullo A, Tatullo M, Abbinante A, Caprio M, Cagiano R, Haragus H. Musculo-skeletal tumors incidence and surgical treatment—a single center 5-year retrospective. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18(24):3898–3901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folpe AL, Lyles RH, Sprouse JT, Conrad EU, 3rd, Eary JF. (F-18) fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography as a predictor of pathologic grade and other prognostic variables in bone and soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(4):1279–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torti SV, Torti FM. Ironing out cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1511–1514. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arredondo M, Núñez MT. Iron and copper metabolism. Mol Aspects Med. 2005;26(4-5):313–327. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitnall M, Howard J, Ponka P, Richardson DR. A class of iron chelators with a wide spectrum of potent antitumor activity that overcomes resistance to chemotherapeutics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14901–14906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604979103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong W, Wang L, Yu F. Regulation of cellular iron metabolism and its implications in lung cancer progression. Med Oncol. 2014;31(7):28. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chanvorachote P, Luanpitpong S. Iron induces cancer stem cells and aggressive phenotypes in human lung cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;310(9):C728–C739. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Zhang F. Iron homeostasis and tumorigenesis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Protein Cell. 2015;6(2):88–100. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0119-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels TR, Delgado T, Rodriguez JA, Helguera G, Penichet ML. The transferrin receptor part I: Biology and targeting with cytotoxic antibodies for the treatment of cancer. Clin Immunol. 2006;121(2):144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosager AM, Sørensen MD, Dahlrot RH, et al. Transferrin receptor-1 and ferritin heavy and light chains in astrocytic brain tumors: Expression and prognostic value. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Lv Y. Suspension state promotes extravasation of breast tumor cells by increasing integrin β1 expression. Biocell. 2018;42:17–24. doi: 10.32604/biocell.2018.06115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhuang M, Peng Z, Wang J. Su X. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms and gastric cancer risk: a meta-analysis. J BUON. 2017;22(3):714–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CC, Michael CW, Pang JC. Fine needle aspiration of primary mediastinal synovial sarcoma: cytomorphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular study. Diagn Cytopathol. 2014;42(2):170–176. doi: 10.1002/dc.22912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yağcı-Küpeli B, Akyüz C, Yalçın B, Varan A, Kutluk T, Büyükpamukçu M. Single institution experience on cancer among adolescents 15-19 years of age. Turk J Pediatr. 2017;59(1):1–5. doi: 10.24953/turkjped.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens RG, Jones DY, Micozzi MS, Taylor PR. Body iron stores and the risk of cancer. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(16):1047–1052. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810203191603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens RG, Graubard BI, Micozzi MS, Neriishi K, Blumberg BS. Moderate elevation of body iron level and increased risk of cancer occurrence and death. Int J Cancer. 1994;56(3):364–369. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knekt P, Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Aromaa A, Heliövaara M, Hakulinen T. Body iron stores and risk of cancer. Int J Cancer. 1994;56(3):379–382. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910560315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson DR, Ponka P. The molecular mechanisms of the metabolism and transport of iron in normal and neoplastic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1331(1):1–40. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4157(96)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faulk WP, Hsi BL, Stevens PJ. Transferrin and transferrin receptors in carcinoma of the breast. Lancet. 1980;2(8191):390–392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)90440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habeshaw JA, Lister TA, Stansfeld AG, Greaves MF. Correlation of transferrin receptor expression with histological class and outcome in non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 1983;1(8323):498–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrba F, Ritzinger E, Reiner A, Holzner JH. Transferrin receptor (TrfR) expression in breast carcinoma and its possible relationship to prognosis. An immunohistochemical study. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1986;410(1):69–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00710908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calzolari A, Oliviero I, Deaglio S, et al. Transferrin receptor 2 is frequently expressed in human cancer cell lines. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;39(1):82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and material are available upon request