Key Points

Question

What is the association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T concentrations, left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions, and risk of heart failure?

Findings

In this analysis of a cohort of 4111 participants without cardiovascular disease, a greater concentration of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T was associated with worse diastolic function but not with systolic function, independent of left ventricular mass. Left ventricular diastolic function accounted for a substantial proportion of the heart failure risk, and preserved ejection fraction was associated with greater high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T concentrations.

Meaning

This study suggests that elevated troponin concentrations may serve as an early marker of subclinical alterations in cardiac structure and diastolic function that predispose a person to developing heart failure.

This cohort study analyzes high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T levels and the associated cardiovascular risks among a cohort of older adults with no cardiovascular conditions enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study.

Abstract

Importance

Cardiac troponin is associated with incident heart failure and greater left ventricular (LV) mass. Its association with LV systolic and diastolic functions is unclear.

Objectives

To define the association of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) with LV systolic and diastolic functions in the general population, and to evaluate the extent to which that association accounts for the correlation between hs-cTnT concentration and incident heart failure overall, heart failure with preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF; HFpEF), and heart failure with LVEF less than 50%.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This analysis of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, an ongoing epidemiologic cohort study in US communities, included participants without cardiovascular disease (n = 4111). Available hs-cTnT measurements for participants who attended ARIC Study visits 2 (1990 to 1992), 4 (1996 to 1998), and 5 (2011 to 2013) were assessed cross-sectionally against echocardiographic measurements taken at visit 5 and against incident health failure after visit 5. Changes in hs-cTnT concentrations from visits 2 and 4 were also examined. Data analyses were performed from August 2017 to July 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cardiac structure and function by echocardiography at visit 5, and incident heart failure during a median 4½ years follow-up after visit 5.

Results

Of the 6538 eligible participants, 4111 (62.9%) without cardiovascular disease were included. Among these participants, 2586 (62.9%) were female, and the mean (SD) age was 75 (5) years. Median (interquartile range) hs-cTnT concentration at visit 5 was 9 (7-14) ng/L and was detectable in 3946 participants (96.0%). After adjustment for demographic and clinical covariates, higher hs-cTnT levels were associated with greater LV mass index (adjusted mean [SE] for group 1: 33.8 [0.5] vs group 5: 40.1 [0.4]; P for trend < .001) and with worse diastolic function, including lower tissue Doppler imaging e’ (6.00 [0.07] vs 5.54 [0.06]; P for trend < .001), higher E/e’ ratio (11.4 [0.2] vs 12.9 [0.1]; P for trend < .001), and greater left atrial volume index (23.4 [0.4] vs 26.4 [0.3]; P for trend < .001), independent of LV mass index; hs-cTnT level was not associated with measures of LV systolic function. Accounting for diastolic function attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with incident HFpEF by 41% and the association with combined heart failure with midrange and reduced ejection fraction combined (LVEF <50) by 17%. Elevated hs-cTnT concentration and diastolic dysfunction were additive risk factors for incident heart failure. For any value of late-life hs-cTnT levels, longer duration of detectable hs-cTnT from midlife to late life was associated with greater LV mass in late life but not with worse LV systolic or diastolic function.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study shows that higher hs-cTnT concentrations were associated with worse diastolic function, irrespective of LV mass, but not with systolic function; these findings suggest that high levels of hs-cTnT may serve as an early marker of subclinical alterations in diastolic function that may lead to a predisposition to heart failure.

Introduction

Cardiac troponin measured by a high-sensitivity assay (hs-cTn) detects low-grade cardiomyocyte damage and is associated with incident heart failure and mortality in the general population1,2,3,4,5 as well as mortality and heart failure hospitalization in patients with heart failure.6,7,8 Increases in hs-cTn concentrations in 2 to 5 years are also associated with mortality among older adults in the community.4,9 Higher hs-cTn concentrations are associated with higher left ventricular (LV) mass in the general population2,10,11 and among patients with heart failure with preserved LV ejection fraction (LVEF; HFpEF).6,12 However, the association of hs-cTn levels with LV function, and diastolic function in particular, is largely uncharacterized. This situation is particularly true in older adults,13,14 among whom diastolic dysfunction prevalence, heart failure prevalence, and heart failure incidence are highest. Diastolic dysfunction shares many risk factors with LV hypertrophy, can occur in the absence of overt ventricular remodeling,15 and has a graded association with mortality and incident heart failure in the general population.16,17,18,19

We hypothesized that higher hs-cTnT (troponin T) concentrations are associated with worse diastolic function and that associated impairments in diastolic function partially account for the heightened risk of heart failure associated with higher hs-cTnT. We also hypothesized that increases in hs-cTnT levels from mid to late life would be associated with greater LV mass and worse diastolic function in late life. We tested these hypotheses in 4111 participants in the community-based Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The ARIC Study is an ongoing epidemiologic cohort study that initially recruited 15 792 men and women aged 45 to 64 years in 4 US communities between 1987 and 1989 (visit 1).20 The concentration of hs-cTnT was measured at visits conducted in 1990 to 1992 (visit 2), 1996 to 1998 (visit 4), and 2011 to 2013 (visit 5). Echocardiography was performed at ARIC Study field centers during visit 5. The study protocol, including the present analysis, was approved by the institutional review boards at each field center, and all participants provided written informed consent.

For this present analysis, participants with prevalent heart failure (n = 965), coronary artery disease (n = 979), atrial fibrillation (n = 649), and/or stroke (n = 229) at visit 5 were excluded,21,22 along with those with missing echocardiography or hs-cTnT measurements (n = 463 [7.1% of the 6538 who attended visit 5]; among those who were alive at the start of visit 5, 3718 [36.2%] did not attend). We assessed the long-term change in hs-cTnT concentrations in participants who had available hs-cTnT measurements at visits 2, 4, and 5.

Echocardiography, Blood Sampling, and Troponin Measurements

Comprehensive 2-dimensional Doppler, tissue Doppler imaging (TDI), and speckle-tracking echocardiography was performed at visit 5 at all sites using uniform imaging software and hardware by a predefined imaging protocol.23 Quantitative measures were performed according to recommendations by the American Society of Echocardiography (eMethods in the Supplement),24 and reproducibility metrics were excellent, as previously reported.23 Diastolic dysfunction was defined as abnormalities in 2 or more of TDI e′, E/e′ ratio, and left atrium (LA) volume index. Concentrations of hs-cTnT were measured with a high-sensitivity sandwich immunoassay from stored plasma samples (–80°C) drawn at visits 2, 4, and 5. The samples were analyzed at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis) and Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas) using high-sensitivity assay (Elecsys Troponin T; Roche Diagnostics) on an automated analyzer (Cobas e411; Roche Diagnostics).25 The limit of detection for hs-cTnT level was 5 ng/L, and the limit of blank was 3 ng/L. Details of assay performance are described in the eMethods in the Supplement. Unmeasurable concentrations of hs-cTnT were entered as 1.5 ng/L (half of the limit of blank). Amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was measured at visit 5 on the automated analyzer.

Clinical Events

Participants in the ARIC Study undergo active surveillance for incident cardiovascular events. Incident heart failure after visit 5 was based on ARIC Study committee adjudication of hospitalizations with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, and Tenth Revision, codes associated with heart failure, which includes abstraction of LVEF during that hospitalization if available, as previously described.26 Heart failure hospitalizations were classified as HFpEF if the LVEF was 50% or greater or as heart failure with midrange or reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF or HFrEF) if the LVEF was less than 50% at the incident hospitalization; if LVEF was not assessed, then the most recent abstracted LVEF within 6 months of the index hospitalization was used. Participants were followed up for incident heart failure through December 31, 2016.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were categorized into 5 groups according to hs-cTnT concentration at visit 5. Group 1 included participants with hs-cTnT below the limit of detection (<5 ng/L). Group 5 included participants with hs-cTnT levels above or equal to the sex-specific 99th percentile upper reference limit (14 ng/L for women and 22 ng/L for men) per the recent recommendations of the US Food and Drug Administration.27 Group 2 (5-7 ng/L for women and 5-9 ng/L for men), group 3 (8-9 ng/L for women and 10-14 ng/L for men), and group 4 (10-13 ng/L for women and 15-21 ng/L for men) were categorized by sex-specific tertiles of hs-cTnT concentrations between group 1 and group 5.

Demographic and echocardiographic variables were compared across hs-cTnT groups, and P for trend was calculated using linear or logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, and race/ethnicity (model 1). For echocardiographic measures, further adjustment was made for body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (based on the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation), and NT-proBNP measured at visit 5 (model 2). The covariates were selected by a priori knowledge. The continuous association between hs-cTnT levels and echocardiographic measurements was assessed with linear regression and with restricted cubic splines to investigate nonlinear associations, as detailed in the eMethods in the Supplement. Effect modification by sex and race/ethnicity was assessed with multiplicative interaction terms in linear regression models. Correlations were calculated by Spearman rank correlation.

The association between the presence of diastolic dysfunction, defined by ARIC Study–derived and American Society of Echocardiography–recommended cutoffs, and hs-cTnT concentration was assessed by multivariable logistic regression (model 2 covariates). The incremental value of hs-cTnT level in estimating diastolic dysfunction was assessed by the increase in the area under the receiver operating curve and the log likelihood from the addition of hs-cTnT concentration to a baseline logistic regression model that included all model 2 covariates (demographics, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, eGFR, and NT-proBNP). To assess the potential implication of bias from selective visit 5 nonattendance among living cohort participants, we performed a sensitivity analysis using inverse probability of attrition weights (eMethods in the Supplement).

To quantify the extent to which associations with LV mass and diastolic function account for the association between hs-cTnT concentrations and incident heart failure (overall, HFpEF, and HFmrEF or HFrEF), we determined the proportional reduction in magnitude of the β coefficient for hs-cTnT in Cox proportional hazards regression models, adjusting for age, sex, and race/ethnicity, and after subsequent adjustment for (1) diastolic function (ie, TDI e′, E/e′ ratio, and LA volume), (2) LV mass, and (3) both diastolic function and LV mass. Associated 95% CIs were obtained from 2000 bootstrap replications using the percentile method. For time-to-event analyses with incident HFpEF as an outcome, participants with incident HFmrEF or HFrEF were censored at the time of heart failure and vice versa for incident HFmrEF or HFrEF.

The association of echocardiographic measures and change in hs-cTnT levels from visits 2 to 4 was assessed within each hs-cTnT concentration category (groups 1-5) at visit 5. Participants were divided in nondetectable (<5 ng/L) and detectable (>5 ng/L) hs-cTnT concentrations at visits 2 and 4. We calculated the trend between participants with stable low (nondetectable at both time points), increasing (nondetectable at visit 2 and detectable at visit 4), and stable high (detectable at both time points) as a measure of temporal exposure of hs-cTnT levels.

A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed from August 2017 to July 2018 using Stata, version 13 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Of the 6538 eligible participants, 4111 (62.9%) without cardiovascular disease were included. Among these participants, 2586 (62.9%) were female, 3215 (78.2%) were white, and the mean (SD) age at visit 5 was 75 (5) years. A total of 6538 (63.8%) of 10 250 surviving participants attended visit 5. The median (interquartile range [IQR]) hs-cTnT concentration was 9 (7-14) ng/L and was detectable in 3946 participants (96.0%) but below the limit of blank (<3 ng/L) in 165 participants (4.0%). A higher group of hs-cTnT concentration was associated with older age, male sex, and black race/ethnicity as well as with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities, higher body mass index and NT-proBNP, and lower eGFR after adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, and sex (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics and Echocardiographic Measurements by High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Concentration at Visit 5a.

| Variable | hs-cTnT Category, Mean (SD) | P Valueb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 413) | Group 2 (n = 1179) | Group 3 (n = 935) | Group 4 (n = 894) | Group 5 (n = 690) | Trend | Adjusted for Trend | |

| hs-cTnT range, ng/L | |||||||

| Women | <5 | 5-7 | 8-9 | 10-13 | ≥14 | NA | NA |

| Men | <5 | 5-9 | 10-14 | 15-21 | ≥22 | NA | NA |

| Age, y | 72.7 (3.7) | 74.1 (4.2) | 75.4 (4.9) | 76.6 (4.9) | 78.1 (5.3) | <.001 | NA |

| Male sex | 61 (14.8) | 418 (35.5) | 469 (50.2) | 335 (37.5) | 242 (35.1) | <.001 | NA |

| White race | 355 (86.0) | 953 (80.8) | 756 (80.9) | 663 (74.2) | 488 (70.7) | <.001 | NA |

| Ever hypertension | 264 (63.9) | 859 (72.9) | 752 (80.4) | 758 (84.8) | 628 (91.0) | <.001 | NA |

| Ever diabetes | 90 (21.8) | 323 (27.4) | 311 (33.3) | 338 (37.8) | 294 (42.6) | <.001 | NA |

| Current smoking | 45 (11.0) | 63 (5.4) | 53 (5.8) | 42 (4.8) | 33 (4.9) | .001 | NA |

| BMI | 27.3 (5.1) | 28.1 (5.1) | 28.4 (5.2) | 29.1 (5.8) | 29.1 (6.1) | <.001 | NA |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||||||

| Diastolic | 67.2 (9.9) | 68.1 (9.8) | 66.9 (10.4) | 66.6 (10.4) | 66.7 (10.8) | .006 | NA |

| Systolic | 127 (17) | 129 (17) | 130 (17) | 131 (17) | 134 (19) | <.001 | NA |

| Heart rate, min | 62.6 (8.9) | 62.0 (9.9) | 61.3 (10.0) | 63.0 (10.5) | 63.6 (10.6) | .002 | NA |

| eGFR, mL/min | 79 (12) | 75 (14) | 72 (15) | 70 (17) | 62 (19) | <.001 | NA |

| HbA1c, No. (%) | 5.7 (0.5) | 5.8 (0.6) | 5.9 (0.8) | 6.0 (0.9) | 6.1 (1.1) | <.001 | NA |

| NT−proBNP, ng/L, median (IQR) | 83 (46-148) | 85 (48-157) | 113 (60-199) | 124 (69-228) | 175 (91-361) | <.001 | NA |

| Echocardiographic measurements | |||||||

| LV septal WT, cm | 0.99 (0.008) | 1.01 (0.004) | 1.02 (0.005) | 1.04 (0.005) | 1.08 (0.006) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LV posterior WT, cm | 0.89 (0.006) | 0.90 (0.004) | 0.91 (0.004) | 0.93 (0.004) | 0.96 (0.005) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LVEDD | 4.28 (0.02) | 4.31 (0.01) | 4.33 (0.01) | 4.41 (0.01) | 4.42 (0.02) | <.001 | .06 |

| LV mass, g | 131.4 (1.8) | 136.1 (1.1) | 139.2 (1.2) | 147.9 (1.2) | 156.5 (1.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LV mass index, g/m2.7 | 33.8 (0.5) | 35.1 (0.3) | 36.1 (0.3) | 38.0 (0.3) | 40.1 (0.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LV hypertrophy | 8.4 (1.3) | 10.9 (0.9) | 13.8 (1.2) | 20.8 (1.4) | 27.9 (1.8) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LV relative WT | 0.42 (0.004) | 0.42 (0.002) | 0.42 (0.002) | 0.42 (0.002) | 0.44 (0.003) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LVEDV index, mL/m2 | 41.9 (0.5) | 42.3 (0.3) | 42.9 (0.3) | 43.4 (0.3) | 44.5 (0.4) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LVEF, % | 66.3 (0.3) | 66.1 (0.2) | 66.2 (0.2) | 65.8 (0.2) | 65.5 (0.2) | .005 | .33 |

| GLS, % | −18.3 (0.1) | −18.3 (0.1) | −18.4 (0.1) | −18.2 (0.1) | −17.8 (0.1) | <.001 | .47 |

| GCS, % | −28.1 (0.2) | −28.0 (0.1) | −28.2 (0.1) | −28.0 (0.1) | −27.8 (0.2) | .40 | .72 |

| TDI e', cm/s | 6.00 (0.07) | 5.84 (0.04) | 5.78 (0.05) | 5.58 (0.05) | 5.54 (0.06) | <.001 | <.001 |

| E/e' ratio | 11.4 (0.2) | 11.5 (0.1) | 11.8 (0.1) | 12.4 (0.1) | 12.9 (0.1) | <.001 | <.001 |

| LAVi, mL/m2 | 23.4 (0.4) | 23.6 (0.2) | 24.6 (0.2) | 25.2 (0.2) | 26.4 (0.3) | <.001 | <.001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GCS, global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; IQR, interquartile range; LAVi, left atrial volume index; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not applicable; NT-proBNP, amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; TDI, tissue Doppler imaging; WT, wall thickness.

Values are presented as mean (SD), No. (%), or median (IQR) for baseline characteristics, and as mean or proportion (SE) adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, and sex for echocardiographic measurements.

P value is for trend from group 1 to group 5. Adjusted P value is adjusted for BMI, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, SBP, heart rate, eGFR, and NT-proBNP, in addition to age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Cardiac Structure and Function and hs-cTnT Group

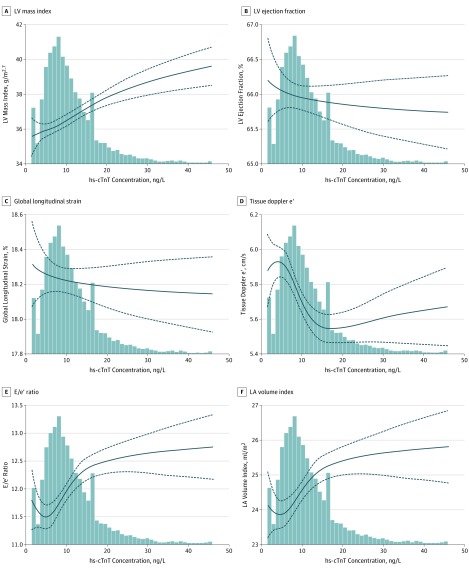

Higher hs-cTnT group was associated with greater LV mass index (adjusted mean [SE] for group 1: 33.8 [0.5] vs group 5: 40.1 [0.4]; P for trend < .001), cavity size (adjusted mean [SE] left ventricular end-diastolic diameter for group 1: 4.28 [0.02] vs group 5: 4.42 [0.02]; P for trend < .001), wall thickness, and prevalence of hypertrophy (group 1: 8.4% vs group 5: 27.9%; P for trend < .001) (Table 1 and Figure 1), which remained statistically significant after full multivariable adjustment (model 2). Higher hs-cTnT groups were associated with worse LVEF (adjusted mean [SE] for group 1: 66.3 [0.3] vs group 5: 65.5 [0.5]; P for trend = .005) and global longitudinal strain (group 1: –18.3 [0.1] vs group 5: –17.8 [0.1]; P for trend < .001) in models adjusting for demographics (model 1) but were not statistically significant after further adjustment (Table 1 and Figure 1). Race/ethnicity and sex did not statistically significantly modify the association of hs-cTnT with LV mass index or with systolic measures.

Figure 1. Fitted Restricted Cubic Splines of Selected Echocardiographic Measures as a Function of Log-Transformed High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T (hs-cTnT) Measured at Visit 5.

Splines were adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, blood pressure, heart rate, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and amino-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide. The best fit for each model was achieved by using 3 knots for LV mass index (A); 4 knots for tissue Doppler e’ (D), E/e’ ratio (E), and left atrium (LA) volume index (F); and a linear model for left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (B) and global longitudinal strain (C). The P values for trend (overall and linear) and P values for nonlinearity for each measure were as follows: A, overall P < .001 and P for nonlinearity = .005; B, linear P = .39; C, linear P = .59; D, overall P < .001 and P for nonlinearity = .001; E, overall P < .001 and P for nonlinearity = .002; and F, overall P < .001 and P for nonlinearity = .03.

Higher hs-cTnT group was associated with lower TDI e′ (adjusted mean [SE] for group 1: 6.00 [0.07] vs group 5: 5.54 [0.06]; P for trend < .001), higher E/e′ ratio (11.4 [0.2] vs 12.9 [0.1]; P for trend < .001), and higher LA volume index (23.4 [0.4] vs 26.4 [0.3]; P for trend < .001), which persisted in fully adjusted models, including NT-proBNP (Table 1). These associations were nonlinear, such that approximately linear associations were observed within the normal range of hs-cTnT level, whereas these associations were less robust at hs-cTnT concentrations above the normal range (Figure 1). No effect modification was noted by sex or race/ethnicity. The association of diastolic measures with hs-cTnT concentrations persisted after further adjustment for LV mass index (P < .001 for e', E/e' ratio, and LA volume index).

Similar associations were observed in the following sensitivity analyses: (1) including all participants with echocardiography and hs-cTnT measurement at visit 5 (ie, 6074 participants with prevalent cardiovascular disease not excluded; eTable 1 in the Supplement); (2) using groups defined by quintiles of hs-cTnT level in the overall analysis population, irrespective of sex (eTable 2 in the Supplement); and (3) incorporating inverse probability of attrition weights to account for possible bias from visit 5 nonattendance (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

hs-cTnT Concentration and Diastolic Dysfunction

Diastolic dysfunction was present in 761 participants (18.7%). In fully adjusted models (model 2), each logarithmic unit increase in hs-cTnT concentration was associated with 37% higher odds of diastolic dysfunction (odds ratio [OR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.61; P < .001), and participants with hs-cTnT levels above the upper reference limit had 45% higher odds of diastolic dysfunction (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.17-1.81; P = .001). Higher hs-cTnT concentration was also associated with abnormalities of each component diastolic measure (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Consistent results were observed when using the American Society of Echocardiography/European Society of Echocardiography criteria for classifying diastolic dysfunction (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Moreover, hs-cTnT measurement provided incremental value beyond established clinical risk factors in identifying participants with diastolic dysfunction as reflected in an increase in the area under the receiver operating curve by 0.90% (95% CI, 0.17%-1.62%) and the likelihood ratio test (266.4 vs 277.5; P < .001).

hs-cTnT Level, Cardiac Structure and Function, and Incident Heart Failure

Incident heart failure occurred in 114 participants (2.8%) during the mean (SD) 4.5 (0.9) years of follow-up after visit 5. Higher hs-cTnT concentrations were associated with higher risk of incident heart failure overall (hazard ratio [HR], 2.58; 95% CI, 1.87-3.57) and incident HFpEF (HR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.39-4.35) per log unit increase in hs-cTnT as well as with HFmrEF or HFrEF individually (HR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.61-4.35 per log unit increase in hs-cTnT (Table 2). Adjusting for LV mass index and diastolic function together attenuated the association of hs-cTnT level with HFpEF by 55% and with HFmrEF or HFrEF by 47%. Adjusting for diastolic function attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with incident HFpEF to a greater extent compared with the association of hs-cTnT level with HFmrEF or HFrEF (41% vs 17%). In contrast, adjusting for LV mass index attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with incident HFmrEF or HFrEF to a greater extent compared with incident HFpEF (47% vs 23%; Table 2). These findings were consistent when also adjusting for hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and eGFR (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association of Log-Transformed High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T Concentrations With Incident Heart Failure .

| hs-cTnT Concentration | Incident HF (114 Events) | Incident HFrEF or HFmrEF (50 Events) | Incident HFpEF (53 Events) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | % Reduction of Coefficient (95% CI)a | HR (95% CI) | % Reduction of Coefficient (95% CI)a | HR (95% CI) | % Reduction of Coefficient (95% CI)a | |

| hs-cTnT (log) | 2.58 (1.87 to 3.57) | 1 [Reference] | 2.65 (1.61 to 4.35) | 1 [Reference] | 2.23 (1.39 to 3.59) | 1 [Reference] |

| hs-cTnT (log) + diastolic function | 1.99 (1.41 to 2.81) | −27 (−13 to −47) | 2.29 (1.35 to 3.88) | −17 (−0.6 to 49) | 1.64 (1.01 to 2.68) | −41 (−14 to −85) |

| hs-cTnT (log) + LV mass index (m2.7) | 1.89 (1.33 to 2.68) | −30 (−13 to −46) | 1.69 (0.97 to 2.93) | −47 (−20 to −112) | 1.79 (1.09 to 2.94) | −23 (−9 to −56) |

| hs-cTnT (log) + diastolic function + LV mass index (m2.7) | 1.66 (1.16 to 2.38) | −46 (−29 to −78) | 1.69 (0.96 to 2.97) | −47 (−20 to −112) | 1.46 (0.88 to 2.43) | −55 (−26 to −123) |

Abbreviations: HF, heart failure; HFmrEF, heart failure with midrange ejection fraction; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; HR, hazard ratio; hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; LV, left ventricular.

Reduction of coefficient is a measure of proportion of the hs-cTnT and outcomes association, accounted for by diastolic function and/or LV mass index. Analyses were restricted to participants with available tissue Doppler e’, E/e’ ratio, left atrium volume index, and LV mass index (n = 3936 [95.7% of the total study population]).

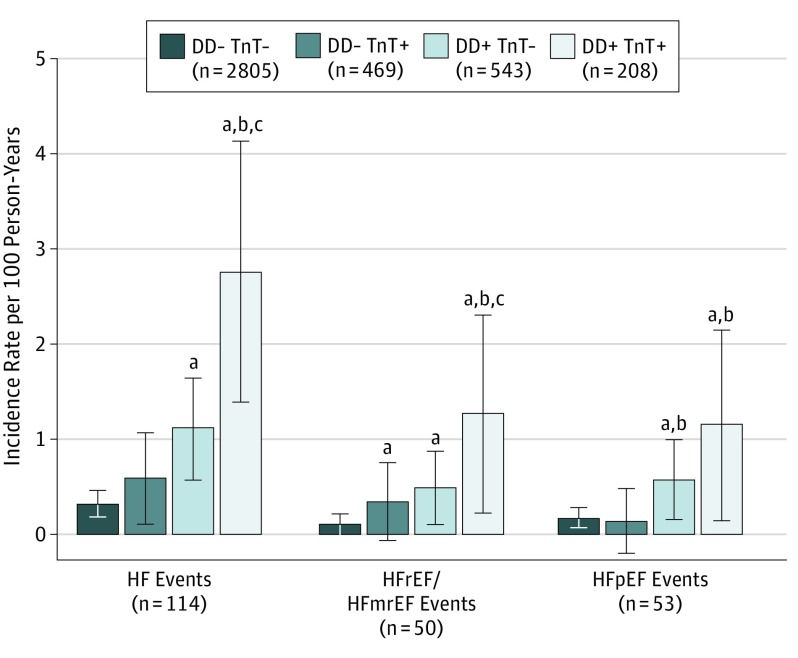

Levels of hs-cTnT and diastolic dysfunction were independently associated with incident heart failure, and participants with both diastolic dysfunction and elevated hs-cTnT concentrations (above the upper reference limit or group 5) were at highest risk (incident rate, 2.76; 95% CI, 1.85-4.12) per 100 person-years (Figure 2). These findings were consistent for incident HFmrEF or HFrEF. However, elevated troponin only appeared associated with incident HFpEF among those with concomitant diastolic dysfunction. These results were consistent when also adjusting for LV mass index (eTable 7 in the Supplement) and when using guideline-recommended cutoffs for diastolic dysfunction (eTable 8 in the Supplement). Associations were attenuated when also adjusting for NT-proBNP, particularly for incident HFrEF, but remained consistent and statistically significant for incident heart failure overall and incident HFpEF (eTable 9 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Incident Rates per 100 Person-Years of Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced or Midrange Ejection Fraction (HFrEF/HFmrEF), and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) .

Rates were based on the presence (+) or absence (–) of diastolic dysfunction (DD) and upper reference limit of hs-cTnT (high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T) concentration (TnT+).

aP < .05 vs DD- TnT- as reference.

bP < .05 vs DD- TnT+ as reference.

cP < .05 vs DD+ TnT- as reference.

Changes in hs-cTnT and Echocardiographic Measures

Among 3573 participants (86.9%) with hs-cTnT measurements at both visits 2 and 4, the median (IQR) hs-cTnT concentration at visit 2 was less than 3 (<3 to 4) ng/L and was below the limit of blank (<3 ng/L) in 2210 (61.9%) of 3573 participants. At visit 4, the median (IQR) hs-cTnT concentration was 4 (<3 to 6) ng/L and was below the limit of blank in 1502 (42.0%) of 3573 participants. The hs-cTnT level increased from visit 2 to visit 5 in 3396 (93.3%) of 3573 participants and from visit 4 to visit 5 in 3379 (90.1%) of 3573 participants.

Greater duration of detectable hs-cTnT level was associated with greater LV mass, volume, and wall thickness at visit 5 (eFigure in the Supplement). These associations were consistent across the hs-cTnT groups at visit 5 (P for interaction > .05 between hs-cTnT group at visit 5 and history of hs-cTnT at visits 2 and 4). For example, participants in the highest hs-cTnT groups at visit 5 with undetectable concentrations at visits 2 and 4 had LV mass comparable to those of participants with undetectable hs-cTnT concentration at visit 5. These results were consistent when replacing raw LV mass with LV mass indexed by body surface area but not when indexing to height (in meters) raised to the 2.7th power. In contrast, no consistent association was noted between duration of detectable hs-cTnT levels and measures of LV diastolic function at visit 5 (eFigure in the Supplement).

Discussion

Among 4111 older adults without cardiovascular disease, higher circulating concentrations of hs-cTnT were independently associated with alterations in LV structure (greater mass, volume, wall thickness, and concentricity) and worse diastolic function (TDI e′, E/e′ ratio, and LA volume) but not with measures of systolic function. The associations between hs-cTnT levels and diastolic function were independent of LV mass, and higher hs-cTnT concentrations were associated with the severity of diastolic dysfunction. Adjusting for diastolic function and LV mass together resulted in an attenuation of the association of hs-cTnT level with incident heart failure by approximately 46%. Diastolic measures attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with incident HFpEF to a greater extent than incident HFmrEF or HFrEF, whereas LV mass attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with HFmrEF or HFrEF to a greater extent. Participants with both diastolic dysfunction and elevated hs-cTnT concentration were at a particularly high risk of heart failure. For any value of late-life hs-cTnT measurement, longer duration of detectable hs-cTnT levels from midlife to late life was associated with greater LV mass in late life but not with worse LV function.

Troponin and Cardiac Structure and Function

These results from a community-based older adult cohort extend the findings of previous studies that hs-cTnT level is associated with measures of LV structure and the risk of incident heart failure overall (Table 3). The key novel finding of the present analysis is the robust association between hs-cTnT levels and measures of diastolic function in these older adults, including TDI e′, E/e′ ratio, and LA size, particularly within the normal range of hs-cTnT concentration. Although the unadjusted association of hs-cTnI (troponin I) level with E/e′ ratio has been previously demonstrated in a middle-aged cohort (mean [SD] age, 55 [11] years) with generally normal diastolic indices,13 the present study included participants with a higher prevalence of abnormal diastolic indices; integrated 3 different measures to assess diastolic function; and adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors, NT-proBNP, and LV mass.

Table 3. Summary of Cohorts of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T, Cardiac Structure and Function, and Heart Failure Riska.

| Source | Population | Exposure | Outcome | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Lemos et al,2 2010 | Dallas Heart Study; mean age: 44 y | Baseline cTnT | (1) LV structure and systolic function |

|

| (2) All-cause and CV death | ||||

| Saunders et al,3 2011 | ARIC Study; mean age: 63 y | Baseline cTnT | (1) Incident CHD; overall HF and all-cause death |

|

| Neeland et al,36 2013 | Dallas Heart Study; mean age: 44 y | Baseline cTnT | (1) LVH |

|

| (2) Incident overall HF; overall and CV deatha | ||||

| McEvoy et al,25 2016 | ARIC Study; mean age: 56 y | Change in cTnT over 6 y | (1) Incident CHD, death, and overall HF |

|

| Seliger et al,10 2017 | MESA Study; mean age: 62 y | Baseline cTnT | (1) 10-y Change in replacement fibrosis, LV structure, and systolic function by cardiac MRI |

|

| (2) Incident CHD, CV death, and overall HF | ||||

| Pandey et al,40 2019 | Jackson Heart Study; median age: 54 y | Baseline cTnI | (1) LVH |

|

| (2) Incident overall HF | ||||

| Jia et al,41 2019 | ARIC Study; mean age: 63 y | Baseline cTnI and cTnT | (1) Incident CVD, CHD, ischemic stroke, death, and HF hospitalizations |

|

| Myhre et al, 2019 (present study) | ARIC Study; mean age: 75 y | (1) Baseline cTnT | (1) LV structure, systolic function, and diastolic function |

|

| (2) change in cTnT over 20 y | (2) Incident HFpEF, HFrEF, and death |

Abbreviations: ARIC, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study; CHD, coronary heart disease; cTnI, cardiac troponin I; cTnT, cardiac troponin T; CV, cardiovascular; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; LV, left ventricular; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

HF was reported as diastolic (n = 10) and systolic (n = 18), but no separate time-to-event analyses were performed for each of these subgroups.

Our findings are consistent with results from studies in isolated cardiomyocytes and transgenic mice, suggesting an association between cardiac troponin and impaired diastolic, but not systolic, function.28,29 Recent research that used invasive hemodynamic assessments of patients with HFpEF at rest and during exercise suggests that elevated LV filling pressures and subendocardial ischemia from impaired myocardial oxygen supply-demand balance are 2 factors in troponin elevation in HFpEF.30 The lack of serial echocardiography in the present study precludes the identification of the temporal association between troponin elevation and diastolic dysfunction, but our findings suggest that these observations extend to older adults without, but are at risk of, HFpEF. Alterations in diastolic function accounted for a sizeable proportion of the association between hs-cTnT level and incident HFpEF in this analysis. The mechanisms linking diastolic dysfunction to elevated troponin and driving oxygen supply-demand mismatch are likely multifold. Although higher hs-cTnT concentrations are independently associated with inducible ischemia among patients with stable coronary artery disease,31 data from patients without overt coronary artery disease suggest an important role for coronary microvascular ischemia.32 Coronary microvascular dysfunction is common in HFpEF, even in the absence of unrevascularized epicardial coronary artery disease.33 Further studies are necessary to define the extent to which microvascular disease mediates the association between diastolic dysfunction and hs-cTnT level in older adults.

Previous studies have demonstrated the associations between cardiac troponin and systolic indices (LVEF and mitral annular plane systolic excursion) in participants with heart failure.34,35 In this study’s older adult population without cardiovascular disease and with largely preserved LVEF, higher hs-cTnT concentration was associated with worse LVEF and global longitudinal strain in unadjusted analysis, which is similar to findings from the Cardiovascular Health Study.4 However, these associations did not persist after accounting for cardiovascular risk factors. These findings are concordant with recent results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which demonstrated hs-cTnT to be a marker of increasing LV mass and LV dilatation but not declining systolic function (measured by cardiac magnetic resonance with a 10-year interval) after covariate adjustment in the general population.10 Participants with prevalent heart failure, and thus most participants with reduced LVEF, were also excluded in this study. Although higher hs-cTn level has been associated with worse systolic function in patients with a more advanced condition, including chronic kidney disease, findings from the present study suggest greater sensitivity of hs-cTnT concentration for alterations in LV mass and diastolic function compared with systolic performance among older adults without cardiovascular disease among whom LVEF is largely preserved.

Prognostic Value of Troponin vs Cardiac Structure and Function

The prognostic value of hs-cTn for mortality and incident heart failure in the general population has been extensively demonstrated,1,2,4 including in the ARIC Study.3 Results of this study suggest that diastolic function accounts for a substantial proportion of the risk of incident heart failure, particularly the risk of incident HFpEF, identified by hs-cTnT measurement in this older population. Hence, elevated hs-cTnT levels may serve as an early marker of subclinical alterations in cardiac structure and diastolic function that predispose individuals to the development of heart failure. Similar to previous findings of additive risk for heart failure between greater LV mass and hs-cTnT concentration,36 we found that participants with both diastolic dysfunction and elevated hs-cTnT level were at statistically significantly higher risk compared with those with only 1 of the 2 present. This pattern was also observed for incident HFpEF and HFmrEF or HFrEF, although our power was limited in these subgroups. Echocardiographic measures of LV structure and function may, therefore, be especially relevant to prognosis in persons with elevated troponin, particularly for incident HFpEF,37 which accounts for most of the heart failure events in older people.38

Change in Troponin From Midlife to Late Life

During the 2 decades preceding visit 5, hs-cTnT concentrations increased in most participants (>90%). Because most participants had unmeasurable hs-cTnT levels in midlife, the increase was highly correlated with the concentration in late life. Despite this, greater duration of hs-cTnT exposure was associated with measures of LV structure beyond the late-life hs-cTnT concentration, including greater LV mass, volume, and wall thickness. In contrast, greater duration of hs-cTnT exposure was not statistically significantly associated with metrics of LV diastolic function beyond the visit 5 value, suggesting that the duration of detectable hs-cTnT level is particularly relevant to LV structure but not to diastolic function.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. We used noninvasive measures of diastolic function because cardiac catheterization is not feasible in a large community-based cohort and diastolic function is most commonly assessed using echocardiography. Although degradation of frozen hs-cTnT samples may cause preanalytical variability, previous data from the ARIC Study show no statistically significant bias when comparing measurements at the different time points.39 Among ARIC study participants who were alive at the start of visit 5, 3718 (36.2%) did not attend this visit, and some were excluded from the analysis owing to missing echocardiography or hs-cTnT measurements (n = 463 (7.1%) of 6538 who attended visit 5). Sensitivity analysis using inverse probability of attrition weights demonstrated similar associations as the primary analysis (eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Conclusions

This study found that, among older adults in a community-based population without overt heart disease, hs-cTnT concentrations were significantly associated with LV diastolic function but not with systolic function, independent of LV mass. Greater duration of detectable hs-cTnT level from mid to late life was associated with worse LV structure but not with diastolic function in late life even after accounting for late-life concentrations. Adjusting for measures of diastolic function and LV mass together attenuated the association of hs-cTnT concentration with incident heart failure by nearly half, with diastolic dysfunction attenuating a relatively larger proportion of the association of hs-cTnT with HFpEF. The presence of both elevated hs-cTnT level and diastolic dysfunction was associated with a particularly high risk of incident heart failure. Elevated troponin may, therefore, serve as an early marker of subclinical alterations in diastolic function that predispose one to heart failure development.

eMethods

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Echocardiographic Measurements According to Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5 in the Total Population That Attended Visit 5 (i.e. Not Excluding Prevalent Cardiovascular Disease)

eTable 2. Echocardiographic Measurements According to Sex-Blinded Categories by Stratifying the Total Population in Quintiles of hs-cTnT at Visit 5, Irrespective of Sex

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics Divided in Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5 of All Participants Alive at Visit 5 by Inverse-Probability-Weighted Estimation Analysis

eTable 4. Associations Between hs-cTnT (per 1 Log Unit Increase) at Visit 5 and Measures of Diastolic Dysfunction According to Validated Cut-offs Derived from the ARIC Study

eTable 5. Associations Between hs-cTnT (per 1 Log Unit Increase) at Visit 5 and Measures of Diastolic Dysfunction According to the Guidelines by American Society of Echocardiography

eTable 6. Association of Log-transformed hs-cTnT Concentrations at Visit 5 Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race, Hypertension, Diabetes, Obesity and eGFR and Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Without and With Adjustment for Measures of Diastolic Function (Tissue Doppler e’, E/e’ and Left Atrial [LA] Volume index) and/or Left Ventricular [LV] Mass Index and LV Hypertrophy

eTable 7. Risk of Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Stratified by the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+) After Adjusting for LV Mass Index

eTable 8. Risk Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Stratified by the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) Classified According to the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) Guidelines and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+)

eTable 9. Incident Rates (per 100 Person-years) of Heart Failure (HF) Overall (114 Events), HF With MidRange or Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFmrEF/HFrEFm 50 Events), and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF, 53 Events) Among Participant Categories Based on the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+)

eFigure. Left Ventricular Mass Index (g/m2), Mean Left Ventricular Wall Thickness (cm), Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index (ml/m2), E/e’-ratio and LA Volume Index (ml/m2) Across Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5, Based on hs-cTnT Measurements at Visit 2 and Visit 4 (Marked as Non-detectable [ND] =<5ng/L and Detectable [D] = ≥5 ng/L)

eReferences.

References

- 1.Zethelius B, Johnston N, Venge P. Troponin I as a predictor of coronary heart disease and mortality in 70-year-old men: a community-based cohort study. Circulation. 2006;113(8):1071-1078. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.570762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Omland T, et al. Association of troponin T detected with a highly sensitive assay and cardiac structure and mortality risk in the general population. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2503-2512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders JT, Nambi V, de Lemos JA, et al. Cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay predicts coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2011;123(13):1367-1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.005264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.deFilippi CR, de Lemos JA, Christenson RH, et al. Association of serial measures of cardiac troponin T using a sensitive assay with incident heart failure and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304(22):2494-2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans JDW, Dobbin SJH, Pettit SJ, Di Angelantonio E, Willeit P. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin and new-onset heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 67,063 patients with 4,165 incident heart failure events. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6(3):187-197.doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santhanakrishnan R, Chong JPC, Ng TP, et al. Growth differentiation factor 15, ST2, high-sensitivity troponin T, and N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide in heart failure with preserved vs. reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14(12):1338-1347. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latini R, Masson S, Anand IS, et al. ; Val-HeFT Investigators . Prognostic value of very low plasma concentrations of troponin T in patients with stable chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1242-1249. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.655076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aimo A, Januzzi JL Jr, Vergaro G, et al. Prognostic value of high-sensitivity troponin T in chronic heart failure: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Circulation. 2018;137(3):286-297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.031560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eggers KM, Venge P, Lindahl B, Lind L. Cardiac troponin I levels measured with a high-sensitive assay increase over time and are strong predictors of mortality in an elderly population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(18):1906-1913. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seliger SL, Hong SN, Christenson RH, et al. High-sensitive cardiac troponin T as an early biochemical signature for clinical and subclinical heart failure: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). Circulation. 2017;135(16):1494-1505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xanthakis V, Larson MG, Wollert KC, et al. Association of novel biomarkers of cardiovascular stress with left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction: implications for screening. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000399. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jhund PS, Claggett BL, Voors AA, et al. ; PARAMOUNT Investigators . Elevation in high-sensitivity troponin T in heart failure and preserved ejection fraction and influence of treatment with the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(6):953-959. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinning C, Keller T, Zeller T, et al. ; Gutenberg Health Study . Association of high-sensitivity assayed troponin I with cardiovascular phenotypes in the general population: the population-based Gutenberg health study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103(3):211-222. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0640-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landesberg G, Jaffe AS, Gilon D, et al. Troponin elevation in severe sepsis and septic shock: the role of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and right ventricular dilatation. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(4):790-800. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon SD, Janardhanan R, Verma A, et al. ; Valsartan In Diastolic Dysfunction (VALIDD) Investigators . Effect of angiotensin receptor blockade and antihypertensive drugs on diastolic function in patients with hypertension and diastolic dysfunction: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2079-2087. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60980-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC Jr, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289(2):194-202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mogelvang R, Sogaard P, Pedersen SA, et al. Cardiac dysfunction assessed by echocardiographic tissue Doppler imaging is an independent predictor of mortality in the general population. Circulation. 2009;119(20):2679-2685. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuznetsova T, Thijs L, Knez J, Herbots L, Zhang Z, Staessen JA. Prognostic value of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in a general population. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(3):e000789. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.000789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah AM, Claggett B, Kitzman D, et al. Contemporary assessment of left ventricular diastolic function in older adults: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2017;135(5):426-439. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687-702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, et al. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: methods and initial two years’ experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(2):223-233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016-1022. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah AM, Cheng S, Skali H, et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter echocardiographic study to assess the relationship between cardiac structure and function and heart failure risk in a biracial cohort of community-dwelling elderly persons: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(1):173-181. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. ; Chamber Quantification Writing Group; American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee; European Association of Echocardiography . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440-1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEvoy JW, Chen Y, Ndumele CE, et al. Six-year change in high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T and risk of subsequent coronary heart disease, heart failure, and death. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(5):519-528. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, et al. Classification of heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: a comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(2):152-159. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peacock WF, Baumann BM, Bruton D, et al. Efficacy of high-sensitivity troponin T in identifying very-low-risk patients with possible acute coronary syndrome. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(2):104-111. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Narolska NA, Piroddi N, Belus A, et al. Impaired diastolic function after exchange of endogenous troponin I with C-terminal truncated troponin I in human cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 2006;99(9):1012-1020. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000248753.30340.af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oberst L, Zhao G, Park JT, et al. Dominant-negative effect of a mutant cardiac troponin T on cardiac structure and function in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;102(8):1498-1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI4088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Melenovsky V, et al. Myocardial injury and cardiac reserve in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(1):29-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myhre PL, Omland T, Sarvari SI, et al. ; DOPPLER-CIP Study Group . Cardiac troponin T concentrations, reversible myocardial ischemia, and indices of left ventricular remodeling in patients with suspected stable angina pectoris: a DOPPLER-CIP Substudy. Clin Chem. 2018;64(9):1370-1379. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2018.288894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taqueti VR, Solomon SD, Shah AM, et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(10):840-849. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah SJ, Lam CSP, Svedlund S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of coronary microvascular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: PROMIS-HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(37):3439-3450. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Natale M, Behnes M, Kim SH, et al. High sensitivity troponin T and I reflect mitral annular plane systolic excursion being assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Med Res. 2017;22(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0281-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shionimya H, Koyama S, Tanada Y, et al. Left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and ejection fraction correlate independently with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin-T concentrations in stable heart failure. J Cardiol. 2015;65(6):526-530. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2014.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neeland IJ, Drazner MH, Berry JD, et al. Biomarkers of chronic cardiac injury and hemodynamic stress identify a malignant phenotype of left ventricular hypertrophy in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(2):187-195. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lam CS, Lyass A, Kraigher-Krainer E, et al. Cardiac dysfunction and noncardiac dysfunction as precursors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in the community. Circulation. 2011;124(1):24-30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.979203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah AM, Claggett B, Loehr LR, et al. Heart failure stages among older adults in the community: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circulation. 2017;135(3):224-240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parrinello CM, Grams ME, Couper D, et al. Recalibration of blood analytes over 25 years in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study: impact of recalibration on chronic kidney disease prevalence and incidence. Clin Chem. 2015;61(7):938-947. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.238873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pandey A, Keshvani N, Ayers C, et al. Association of cardiac injury and malignant left ventricular hypertrophy with risk of heart failure in African Americans: The Jackson Heart Study. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(1):51-58. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.4300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jia X, Sun W, Hoogeveen RC, et al. High-sensitivity troponin I and incident coronary events, stroke, heart failure hospitalization, and mortality in the ARIC study. Circulation. 2019;139(23):2642-2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Echocardiographic Measurements According to Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5 in the Total Population That Attended Visit 5 (i.e. Not Excluding Prevalent Cardiovascular Disease)

eTable 2. Echocardiographic Measurements According to Sex-Blinded Categories by Stratifying the Total Population in Quintiles of hs-cTnT at Visit 5, Irrespective of Sex

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics Divided in Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5 of All Participants Alive at Visit 5 by Inverse-Probability-Weighted Estimation Analysis

eTable 4. Associations Between hs-cTnT (per 1 Log Unit Increase) at Visit 5 and Measures of Diastolic Dysfunction According to Validated Cut-offs Derived from the ARIC Study

eTable 5. Associations Between hs-cTnT (per 1 Log Unit Increase) at Visit 5 and Measures of Diastolic Dysfunction According to the Guidelines by American Society of Echocardiography

eTable 6. Association of Log-transformed hs-cTnT Concentrations at Visit 5 Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race, Hypertension, Diabetes, Obesity and eGFR and Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Without and With Adjustment for Measures of Diastolic Function (Tissue Doppler e’, E/e’ and Left Atrial [LA] Volume index) and/or Left Ventricular [LV] Mass Index and LV Hypertrophy

eTable 7. Risk of Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Stratified by the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+) After Adjusting for LV Mass Index

eTable 8. Risk Incident Heart Failure (HF), HF With Reduced (HFrEF) or Midrange Ejection Fraction (EFmrEF) and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) Stratified by the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) Classified According to the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) Guidelines and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+)

eTable 9. Incident Rates (per 100 Person-years) of Heart Failure (HF) Overall (114 Events), HF With MidRange or Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFmrEF/HFrEFm 50 Events), and HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF, 53 Events) Among Participant Categories Based on the Presence (+) or Absence (-) of Diastolic Dysfunction (DD) and hs-cTnT > Upper Reference Limit (TnT+)

eFigure. Left Ventricular Mass Index (g/m2), Mean Left Ventricular Wall Thickness (cm), Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index (ml/m2), E/e’-ratio and LA Volume Index (ml/m2) Across Categories of hs-cTnT at Visit 5, Based on hs-cTnT Measurements at Visit 2 and Visit 4 (Marked as Non-detectable [ND] =<5ng/L and Detectable [D] = ≥5 ng/L)

eReferences.