Abstract

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) provides breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services to low-income, uninsured, and underinsured women across the nation. Although the program has provided services to more than 5 million women since 1991, there remains a significant burden of breast and cervical cancer with inequities among certain populations. To reduce this burden and improve health equity, the NBCCEDP is expanding its scope to include population-based strategies to increase screening in health systems and communities through the implementation of patient and provider evidence-based interventions, connecting women in communities to clinical services, increasing opportunities to access screening, and enhancing the targeting of women in need of services. The goal is to reach more women and make sure women are getting the right screening test at the right time.

Keywords: breast cancer, cervical cancer, screening, health equity, low income

Introduction

CANCER IS A MAJOR cause of death and disability in the United States. Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths among women across the United States.1 Although the incidence of, and mortality due to, cervical cancer has decreased over the past five decades, it still remains a significant burden to some groups of women.1 To reduce breast and cervical cancer burden, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine screening for both these cancers for women of certain ages.2,3 The goal of screening is to find invasive cancer or premalignant lesions early, when treatment is most effective or invasive cancer can be prevented. However, access to screening and treatment is not equally attained by all women, especially those who are uninsured, with a low income level, or have disabilities.4,5 To reduce breast and cervical cancer mortality among low-income women who do not have access to medical services, Congress created the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) through the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 1990.6

The NBCCEDP is managed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and began screening women through funded state health departments in 1991. Currently the program funds all the 50 states, the District of Columbia, 13 tribes/tribal organizations, and 6 U.S. territories.7 This program is the only nationwide organized breast and cervical cancer screening program in the United States, serving more than 5 million women over its 27 years of existence. Along with a national infrastructure of awardee-established screening provider networks, the NBCCEDP monitors program activities to assure provision of quality services and timely follow-up.

Program Activities

Historically, the emphasis of the NBCCEDP has been to provide direct breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic services for low-income uninsured and under-insured women as authorized in the Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 1990.6 Health departments (or their bona fide agents) receive funding from the CDC and contract with health care delivery systems in their communities to provide a broad range of clinical services. Women diagnosed with cancer or premalignant lesions may be referred for treatment to the state’s Medicaid program under the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000 (BCCPTA)8 and the Native American Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Technical Amendment Act of 2001.9 Throughout the screening and diagnostic process, women are offered patient navigation services to assist with overcoming barriers that may interfere with accessing and completing appropriate screening and diagnostic care.

In addition, the NBCCEDP has a comprehensive approach to increasing cancer screening by providing other supportive activities.10,11 Public education and outreach help to increase awareness and motivate women to get screened. Professional development keeps providers updated on evidence-based clinical standards regarding breast and cervical cancer screening and diagnostic pathways. Quality assurance and quality improvement processes ensure that women receive appropriate clinical testing and follow-up. Together, these activities maximize the quality of care that women receive.

To implement an organized national screening approach, CDC established program policies, including eligibility and reimbursement criteria for the program.12 Low income is defined as family income at or below 250% of the federal poverty level. The target eligibility age is women 40–64 years for breast cancer and 21–64 years for cervical cancer, consistent with the age for screening recommendations. Women ages 65 and older are typically eligible for screening under Medicare. However, any woman age 65 and older who does not qualify for Medicare or who cannot afford Medicare Part B premium is eligible to receive NBCCEDP services. In an effort to direct clinical services to women who are most at-risk, the program prioritizes women ages 50–64 years for breast cancer screening and women who are rarely or never screened for cervical cancer screening.12

Program Evaluation

Since 1991, the NBCCEDP has served more than 5 million women; provided more than 12 million breast and cervical cancer screening examinations; and found nearly 65,000 invasive breast cancers, 4500 invasive cervical cancers, 21,000 premalignant breast lesions, and 204,000 premalignant cervical lesions.7 Program evaluation is essential for guiding program planning, development, and implementation. CDC has placed a high priority on evaluating the effectiveness of the NBCCEDP and used the findings to continuously make program improvements.

The NBCCEDP collects clinical data on each patient encounter to monitor the services provided and ensure accountability relative to appropriate services and timely follow-up. CDC supports the extensive data management requirements of awardees to maintain data quality.13 Standardized data are reported to CDC biannually that describe the demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes of the women served. Summary feedback reports of the analyzed clinical data are subsequently shared with each awardee for use. These data are used for program management, ongoing quality assurance/quality improvement, program planning, and program evaluation. These data have also been instrumental in helping to shape program policy development at CDC and in Congress. For example, data on the time delays and efforts required by the NBCCEDP awardees to secure pro-bono treatment for uninsured women diagnosed with cancer informed Congress ’ decision to pass the BCCPTA.14

While the NBCCEDP has served many women, this is only a small percentage of the women eligible for the program. Using the U.S. Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey and the NBCCEDP’s data for 2010–2012, there were 9.8 million low-income women in the United States who were eligible for NBCCEDP cervical cancer services. However, only 6.5% of eligible women were served by the program, while 60.2% of eligible women were screened for cervical cancer outside the program.15 As for breast cancer screening, data from 2011 to 2012 identified ~5.2 million low-income women eligible for the NBCCEDP, with 10.6% served by the program and 30.6% screened outside the program.16 A study by Ku et al. assessing the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act projected that the uninsured rate among women eligible for the NBCCEDP would decrease significantly, but ~5.7 million low-income women would remain uninsured by 2017.17 These data indicate that there were still women not being screened and that CDC could consider other options to increase the cancer screening rates for low-income women.

New Program Activities

In 2016, CDC began to explore untapped opportunities to reach more women in need of screening for breast and cervical cancer, especially low-income women. Following the model set by CDC’s Colorectal Cancer Control Program (CRCCP),18 strategies to increase clinic-level screening rates were incorporated into the new NBCCEDP funding opportunity.19 Hence, the NBCCEDP awardees now partner with clinics that serve low-income women and help implement evidence-based interventions (EBIs) known to be effective in increasing breast and cervical cancer screening. In 2015, CRCCP began to focus directly on implementing EBIs recommended by the Guide to Community Preventive Services20 as effective in increasing colorectal cancer screening in clinics. A 4.4 percentage point increase in clinic-level screening rates was achieved in the first program year.18 These promising findings offer a model for the NBCCEDP to expand its reach and help more women get screened for breast and cervical cancer through collaboration with health systems and clinics to effectively utilize EBIs such as patient and provider reminders, provider screening performance feedback reports, and interventions to reduce structural barriers.20

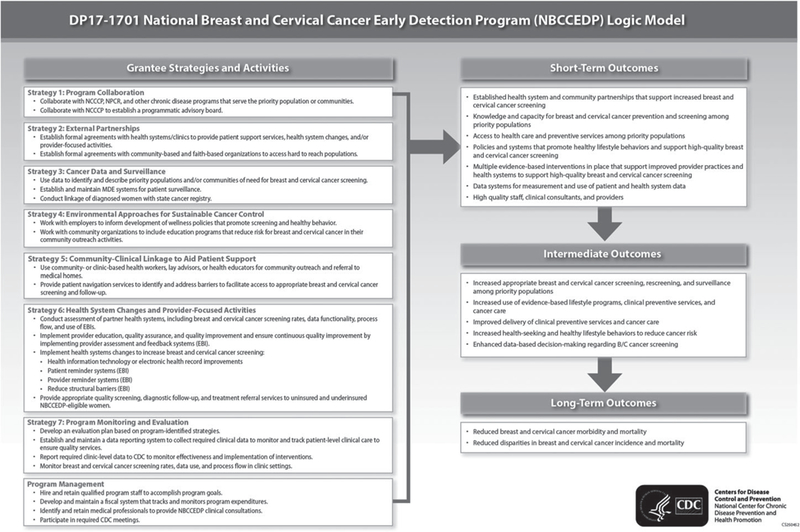

Other new areas of emphasis include community/clinical linkages and environmental approaches. For community/clinical linkages, awardees work with community organizations to connect disadvantaged women who need screening to appropriate cancer screening services at partner health clinics in their community. For environmental approaches, awardees collaborate with employers and other organizations to implement worksite policies that help women gain access to and support the completion of screening. The NBCCEDP logic model (Fig. 1) outlines awardees’ strategies and activities supported by CDC funding along with the expected short-term, intermediate-term, and long-term outcomes.

FIG. 1.

National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program logic model. NCCCP, National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program; NPCR, National Program of Cancer Registries; MDE, minimum data elements; EBI, evidence-based interventions; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, complementary activities such as the development of well-designed small media, delivery of continuing education for providers and health system partners, and improvement in the use of electronic health records are supported. Increasing the use of data to better target interventions and allocate limited resources is another important activity. Data are used to identify disparate populations (e.g., low income, uninsured, high cancer incidence and death rates, low screening rates) and geographic areas (e.g., states, counties, cities) in greater need of screening. Data help inform which interventions are needed and appropriate, and how resources can be allocated to improve health equity. Multiple other data sources with state- and substate (e.g., county, city)-level information are available to NBCCEDP directors to help inform their planning.21–23

Public Health Implications

With an eye farther into the future, the NBCCEDP is a critical public health program in helping women getting the right breast and cervical cancer screening test at the right time. CDC’s strengths in data, translation, evaluation, and partnerships could help facilitate progress toward achieving this goal. Specifically, the NBCCEDP is working toward improving cancer screening across the United States and identifying best practices that work in different settings and among different populations for scaling and replication in other settings across the country.19

In expanding the NBCCEDP’s scope, it is important to clearly communicate the evolution of the program to embrace underutilized opportunities to increase cancer screening rates on a population level; and to encourage the support and participation of stakeholders who are essential partners in making health systems’ and clinic-based interventions successful and sustainable. To address this communication priority, CDC has developed a new visual brand for CDC’s cancer screening programs in partnership with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors–ScreenOutCancer: Advancing Cancer Prevention Nationwide.24 The ultimate goal communicated by the brand is simple and clear—to “Screen. Out. Cancer.” The tagline, “Advancing Cancer Prevention Nationwide,” brings together the efforts of CDC and its awardees across the United States to collectively achieve a common goal.

Across the nation, the NBCCEDP has nearly three decades of public health experience, leadership, and data, plus established cancer screening infrastructures and partnerships, to build on and share with health systems and other new partners as awardees pursue population-based approaches to increase cancer screening rates. Addressing inequities in breast and cervical cancer and fully utilizing available data to target geographic areas and populations with high disease burden and low screening rates will continue to be important.25,26 Awardees can work with providers and clinics that serve a high proportion of low-income populations in need of screening; these include community health centers, safety net hospitals, rural health clinics that serve geographically isolated communities, and urban and minority health clinics located in low-income neighborhoods that serve a diverse populations.

In summary, the NBCCEDP has embarked on new strategies to raise population-level cancer screening rates while continuing to meet its central purpose to serve at-risk women by providing them with direct screening services for breast and cervical cancer. We have strategically mapped out forward-thinking goals and core strategies, and are applying our nearly three decades of expertise, experience, and established infrastructure to maximize the likelihood of success in the future while we build new expertise and capacity in collaborating with health systems.19 The NBCCEDP is working to reach more women, especially among populations that have high disease burden and persistent low screening rates. CDC awardees can put successful processes into practice across the nation to increase breast and cervical cancer screening rates.

Acknowledgments

The NBCCEDP is currently supported by the CDC cooperative agreement DP17–1701. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. U.S. Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on November 2017 submission data (1999–2015): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; Available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz Accessed January 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Final Update Summary: Breast Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; February 2018. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/breast-cancer-screening1. Accessed January 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Final Update Summary: Cervical Cancer: Screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; August 2018. Available at: www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening2 Accessed January 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steele CB, Townsend JS, Courtney-Long EA, Young M. Cancer screening prevalence among adults with disabilities, United States, 2013. Prev Chronic Dis 2017;14:160312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White A, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Cancer screening test use—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breast and Cervical Cancer Mortality Prevention Act of 1990. Pub L 301–354. Available at: http://uscode.http://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/101/354.pdf Accessed December 28, 2018.

- 7.CDC. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: About the program. Available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/about.htm Accessed December 28, 2018.

- 8.Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000. Pub L 106–354. Available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/pdf/publ354–106.pdf Accessed December 28, 2018.

- 9.Native American Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Technical Act of 2001. Available at: www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-107s1741enr/pdf/BILLS-107s1741enr.pdf Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 10.Miller JW, Plescia M, Ekwueme DU. Public Health National Approach to reducing breast and cervical cancer disparities. Cancer 2014;120 Suppl 16:2537–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: The NBCCEDP conceptual framework. Available at: www.cdc.gov/cancer/nbccedp/concept.htm Accessed December 28, 2018.

- 12.Lee NC, Wong FL, Jamison PM, et al. Implementation of the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program: The beginning. Cancer 2014;120 Suppl 16:2540–2548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancy B, Royalty JE, Marroulis S, Mattingly C, Benard VB, DeGroff A. Using data to effectively manage a national screening program. Cancer 2014;120 Suppl 16:2575–2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lantz PM, Weisman CS, Itani Z. A disease-specific Medicaid expansion for women: The Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 2000. Womens Health Issues 2003;13:79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tangka FK, Howard DH, Royalty J, et al. Cervical cancer screening of underserved women in the United States: Results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1997–2012. Cancer Causes Control 2015;26:671–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard DH, Tangka FK, Royalty J, et al. Breast cancer screening of underserved women in the USA: Results from the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1998–2012. Cancer Causes Control 2015;26:657–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ku L, Bysshe T, Steinmetz E, Bruen BK. Health reform, Medicaid expansions, and women’s cancer screening. Womens Health Issues 2016;26:256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGroff A, Sharma K, Satsangi A, et al. Increasing colorectal cancer screening in health care systems using evidence-based interventions. Prev Chronic Dis 2018;15:180029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. Cancer Prevention and Control Programs for State, Territorial, and Tribal Organizations. Available at: www.grants.gov/web/grants/search-grants.html?keywords=dp17-1701 Accessed January 9, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org Accessed January 8, 2019.

- 21.CDC. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Available at: www.cdc.gov/brfss Accessed January 9, 2019.

- 22.Berkowitz Z, Zhang X, Richards TB, et al. Multilevel regression for small-area estimation of mammography use in the United States, 2014. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2019;28:32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berkowitz Z, Zhang X, Richards TB, et al. Multilevel small-area estimation of colorectal cancer screening in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2018;27: 245–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC. Screen Out Cancer. Available at: www.cdc.gov/screenoutcancer/index.htm Accessed December 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller JW, Lee Smith J, Ryerson AB, et al. Disparities in breast cancer survival in the United States (2001–2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer 2017;123 Suppl 24:5100–5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benard V, Watson M, Saraiya M, et al. Cervical cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001–2009): Findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer 2017;123 Suppl 24:5119–5137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]