Abstract

A 45-year-old woman with hypothyroidism that has been treated with a stable dose of levothyroxine presents to her primary care provider with depressed mood, negative feelings about herself, poor sleep, low appetite, poor concentration, and lack of energy. These symptoms began several months ago during a conflict with her partner. Although she has been able to continue with work and life responsibilities, she feels sadness most days and occasionally thinks that she would be better off dead. How would you evaluate and treat this patient?

THE CLINICAL PROBLEM

DEPRESSION IS A CLINICSLLY SIGNIFICANT AND GROWING PUBLIC health issue. In 2015, depressive disorders were estimated to be the third leading cause of disability worldwide.1 In the United States, the estimated lifetime risk of a major depressive episode now approaches 30%.2 The incidence of suicide — which is associated with a diagnosis of depression more than 50% of the time3 — has been increasing and is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.4

Major depressive disorder is a heterogeneous condition with a variety of presentations and a broad constellation of associated symptoms. The criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition,5 for diagnosing and rating the severity of major depressive disorder are listed in Table 1. The pathophysiology of depression remains incompletely understood. Decreased functioning of monoaminergic neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, or all of these neurotransmitters) in the brain has traditionally been implicated, with presumed correction of these functional deficits in response to effective antidepressant therapies. As the understanding of depression evolves to implicate processes of neuroplasticity — that is, functional changes, structural changes, or both in the brain in response to the environment and experience — such monoaminergic mechanisms are seen in the context of a host of molecular and cellular mechanisms that mediate human emotion.6

Table 1.

DSM-5 Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder.*

| Criteria |

| Five or more of the following symptoms during the same 2-wk period, with the symptoms representing a change from previous functioning and with at least one of the symptoms being either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure in activities of daily life (symptoms that are clearly attributable to another medical condition are not included). |

| 1. Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g.,feels sad, empty, or hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful). (In children and adolescents, a depressed mood can be an irritable mood.) |

| 2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation). |

| 3. Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of >5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. (In children, failure to gain expected weight should be considered.) |

| 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day. |

| 5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others, not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down). |

| 6. Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day. |

| 7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick). |

| 8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others). |

| 9. Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide. |

| Severity of depression |

| Mild depression: Few, if any, symptoms in excess of those required to make the diagnosis are present, the intensity of the symptoms is distressing but manageable, and the symptoms result in minor impairment in social or occupational functioning. |

| Moderate depression: The number of symptoms, intensity of symptoms, functional impairment, or all of these variables are between those specified for “mild” and “severe.” |

| Severe depression: The number of symptoms is substantially in excess of that required to make the diagnosis, the intensity of the symptoms is seriously distressing and unmanageable, and the symptoms markedly interfere with social and occupational functioning. |

| A comprehensive assessment of depression should not rely simply on a symptom count but should take into account the degree of functional impairment, disability, or both. |

In contrast to major depressive disorder, the diagnosis of bipolar depression is based on the occurrence of a past or present hypomanic episode (symptoms present ≥4 days) or manic episode (≥1 week). A hypomanic episode involves elevated, expansive, or irritable mood; grandiosity; decreased need for sleep; pressured or increased speech; flight of ideas or racing thoughts; distractibility; increased goal-directed activity; psychomotor agitation; or excessive involvement in activities with high potential for painful consequences. The criteria for major depressive disorder are from the American Psychiatric Association.5 DSM-5 denotes Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition.

The onset of major depressive disorder is bimodal; most patients present in their twenties,7 and a second peak occurs in the fifties.8 Women are twice as likely to have depression as men.9 Other risk factors for the development of major depressive disorder include being divorced or separated,10 previous episodes of depression, elevated levels of stress, a history of trauma, and a history of major depressive disorder in first-degree relatives.5 In patients with major depressive disorder, coexisting anxiety, psychotic symptoms, substance abuse, and borderline personality disorder are associated with a poorer prognosis, as well as a longer duration of episodes and greater symptom severity.5 In particular, the overlap between depression and anxiety has been well established; more than 50% of patients with depression report clinically significant anxiety and have greater refractoriness to standard treatments than patients who have depression without anxiety.11

Primary care providers are important in recognizing and managing depression. An estimated 60% of mental health care delivery occurs in the primary care setting,12 and 79% of antidepressant prescriptions are written by providers who are not mental health care providers.13 One study showed that among persons who have attempted suicide, 38% visited a health care provider within the previous week, and 64% visited a health care provider within 4 weeks before the attempt; most of these patients visited a primary care practice.14 Despite efforts to educate patients, communities, and medical professionals, stigma remains a primary barrier to recognizing and providing treatment for mental illness.15

STRATEGIES AND EVIDENCE

SCREENING

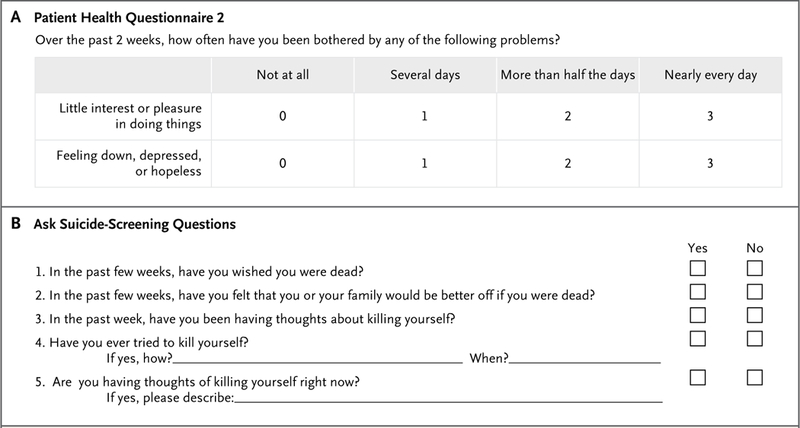

Universal screening for depression in all adult patients in the primary care setting, including pregnant and postpartum women, has been recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.16 The Joint Commission recommends screening for suicidal ideation in patients in all medical settings.17 Brief screening instruments for depression such as the Patient Health Questionnaire 218,19 and the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions20 (Fig. 1) may be effectively and efficiently administered in the outpatient setting. Although some past studies suggested that screening for depression and suicide was not cost-effective, more recent studies have shown that cost-effectiveness ratios for outpatient and emergency-department screening were on par with preventive interventions for other medical conditions,21,22 perhaps because of the use of more efficient screening tools and the increased incidence of these conditions.

Figure 1. Depression and Suicide Screening Tools.

On the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (Panel A), a score of 3 or higher is 83% sensitive and 90% specific for a diagnosis of major depression. On the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (Panel B), if the patient answers “no” to all four questions 1 through 4, the screening is complete and it is not necessary to ask question 5. No intervention is necessary (clinical judgment can always override a negative screening test). If the patient answers “yes” to any of questions 1 through 4 or declines to answer, the screening test is considered to be positive, and question 5 should be asked to assess severity. If the patient answers “yes” to question 5, the test is considered to be positive with an imminent risk identified. The patient requires immediate safety and a full mental health evaluation and cannot leave until he or she is evaluated for safety. Keep the patient in sight, remove all dangerous objects from the room, and alert the physician or clinician who is responsible for the patient’s care. If the patient answers “no,” the screening test is considered to be a positive test with a potential risk identified. He or she requires a brief suicide safety assessment to determine whether a full mental health evaluation is needed and cannot leave until he or she is evaluated for safety. Alert the physician or clinician who is responsible for the patient’s care. Data are adapted from www.nimh.nih.gov/labs-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/index.shtml#outpatient.

ASSESSMENT

Potential causative or contributing medical diagnoses are a core consideration in the initial assessment of patients who present with any psychiatric symptoms. In the general hospital setting, up to one third of patients who present with depressive symptoms may have an underlying medical condition.23 For instance, manifestations of dementia and delirium, including loss of social interactions, negative mood states, and cognitive dysfunction, may be similar to those of major depressive disorder. Multiple other medical conditions have been associated with depressive symptoms; these conditions include anemia, hypothyroidism, seizures, Parkinson’s disease, sleep apnea, deficiencies of vitamins such as B12 and folate, and infectious diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, syphilis, and Lyme disease.24 In some cases, treatment of these underlying conditions may decrease or resolve depressive symptoms.

Because both prescribed and illicit substances can also result in depressive symptoms, the patient history should include assessment of the use of drugs such as beta-blockers, barbiturates, anabolic steroids and glucocorticoids, statins, hormones (e.g., oral contraceptives), levodopa and methyldopa, opioids, and some antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones, mefloquine, and metronidazole).25 Illicit use of or withdrawal states associated with marijuana, sedatives or hypnotics, opiates, cocaine, or stimulants may also lead to depressive symptoms.

In addition to a comprehensive history and physical examination, laboratory testing should be considered in any initial evaluation of patients with depressive symptoms. Although empirical data supporting particular tests are generally scant, initial screening tests should include complete blood counts and differential blood counts, basic metabolic studies, thyroid-function tests, and levels of vitamin B and folate. Other laboratory tests such as liver-function tests, testosterone levels (in men), a Lyme titer, a rapid plasma reagin test, an HIV test, and urine and serum toxicologic screening should be considered as clinically appropriate.

In addition, a detailed psychiatric interview is important to accurately characterize psychiatric symptoms and assess the effect of symptoms on functioning. Establishing an effective therapeutic alliance with the patient requires sufficient time and attention to matters of a sensitive nature. Family, friends, partners, and other health care providers may be valuable sources of information; in nonemergency circumstances, patient permission is required to contact these persons. Consideration of cultural, social, and situational factors may help to identify relevant stressors, precipitants, or other situational variables that can affect functioning and guide decisions regarding treatment.

Other possible coexisting psychiatric diagnoses should also be considered. In particular, major depressive disorder should be distinguished from bipolar depression. Bipolar disorder, which is defined by current or past manic or hypomanic episodes, often presents as a depressive episode.26 Because the clinical presentation of bipolar depression may be clinically indistinguishable from that of major depressive disorder, the diagnosis hinges on an assessment of past hypomanic or manic episodes (Table 1). This distinction also has therapeutic significance, since the use of antidepressants in bipolar depression without concurrent treatment with a mood stabilizer is associated with an increased risk of manic symptoms (i.e., “switching,” or depression turning into hypomania or mania).

TREATMENT

General agreement exists regarding the initial treatment of mild-to-moderate major depressive disorder in adults.27 For mild depression, initial preference should be given to psychotherapy and symptom monitoring, with pharmacotherapy re-served for cases of insufficient improvement. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both should be considered for moderate depression.28 Con-sultation with a psychiatrist should be obtained for a patient with severe depression and urgently in any patient with psychotic symptoms or suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapeutic interventions are first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate depression.29 A metaanalysis of various psychotherapies, including 53 comparative trials (involving 2757 patients with mild-to-moderate depression) showed that across all forms of psychotherapy, the response rate was 48% (vs. 19% in the control groups).29 No significant differences were noted among various types of psychotherapy, including — but not limited to — cognitive behavioral therapy (identifying and modifying negative thoughts that adversely affect emotion and behavior), behavioral activation (scheduling positive activities and increasing positive interactions), and interpersonal psychotherapy (addressing interpersonal issues in a highly structured manner). Another meta-analysis showed significantly higher remission rates among patients who received psychotherapy (i.e., cognitive behavioral therapy [66%], psychodynamic therapy [54%], supportive counseling [49%], and behavioral activation [74%]) than among those in control conditions (43%).30 In order to gain a better sense of the clinical effect, a meta-analysis comparing cognitive behavioral therapy with various control conditions showed a moderate effect size and a number needed to treat of 2.6 to see improvement.31 Taken together, the data provide support for cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and behavioral activation as first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate depression.32 Data have shown some effectiveness of tele-phone-based33 and Internet-based34 psychotherapeutic interventions, and these interventions may be considered, particularly if in-person therapy is not accessible.

The type of psychotherapy should be appropriate for the patient’s situation. For instance, interpersonal psychotherapy may help when interpersonal issues are prominent, behavioral activation may increase motivation and initiative, and cognitive behavioral therapy may help to modify distorted thoughts that contribute to depression. If substantive improvement is not seen after 6 weeks of a psychotherapeutic intervention, a change in the type of psychotherapy, initiation of pharmacotherapy, or psychiatric consultation should be considered.

Pharmacotherapy

Antidepressant medications have been a mainstay of treatment for depression, although the favorability of the benefit-risk analysis for milder forms of depression has been questioned.35 A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressants showed that effect sizes varied according to the severity of baseline depression; effect sizes were small in cases of mild depression but greater in moderate-to-severe depression.36

Although well-controlled randomized trials are the standard for assessing efficacy, it can be challenging to translate these findings into clinical effectiveness; notably, many of these trials are associated with high placebo response rates. Information on “real-world” effectiveness was provided by the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, which used a four-level algorithm (reflecting clinical practice at the time) to guide the selection of antidepressant therapies. Citalopram was prescribed as the first (level 1) treatment. If that treatment was unsuccessful, patients underwent randomization to receive alternative therapies within a group of substrategies that the patients had deemed to be acceptable. Level 2 choices included continuation of citalopram, a change to another commonly used medication (sertraline, venlafaxine, or bupropion), or the addition of another medication or cognitive behavioral therapy. Subsequent levels involved switching to or adding less frequently used medications. Treatment with citalopram yielded a response rate of 47% and a remission rate of 37%; the cumulative remission rate of all four levels was 67%.37 The STAR*D trial also showed that none of the antidepressants that were examined were superior to any other and that, after a failed antidepressant trial, switching or augmentation strategies (including with cognitive behavioral therapy) resulted in similar response rates.38

Although the STAR*D trial was limited by the lack of strict randomization and blinding, other analyses have similarly shown no significant differences in efficacy among antidepressant drugs.39 For example, an international, randomized, multicenter trial comparing escitalopram, sertraline, and extended-release venlafaxine showed no significant differences in rates of response at 8 weeks (61%, 66%, and 60%, respectively) or remission (48%, 46%, and 42%, respectively) among the treatments.40 A recent meta-analysis of 522 mostly short-term trials involving patients with moderate-to-severe depression showed that all the assessed antidepressants were more effective than placebo (although with modest effect sizes)41; the same meta-analysis also showed that in head-to-head trials, certain antidepressants (including amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and vortioxetine) were more effective than others.

For moderate-to-severe depression, first-line medications generally include selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepi-nephrine-reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), bupropion, and mirtazapine (Table 2).42 Three drugs more recently approved by the FDA for depression — vilazodone, vortioxetine, and levomilnacipran — are also treatment options, but current guidelines (with the exception of the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [CANMAT] guidelines42) precede these agents. Among the newer agents, the CANMAT guidelines include vortioxetine and milnacipran (a racemic mixture of levomilnacipran and its dextrorotatory enan-tiomer) as first-line options and vilazodone as a second-line option. Older classes of antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors have a greater risk profile than newer agents, so they are typically used only if other agents are ineffective.

Table 2.

First-Line Antidepressant Medications for Major Depressive Disorder.*

| Drug Class and Agent | Dose | Adverse Effects | Clinical Considerations | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRIs† | ||||

| Fluoxetine | 20–80 mg/day | Gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, agitation | Long-acting active metabolites decrease risk of discontinuation syndrome‡; 1-wk washout required when switching to another SSRI or SNRI; increased risk of drug interactions | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for PMDD, OCD, bulimia, panic disorder |

| Sertraline | 50–200 mg/day | Gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, headache; generally acceptable side-effect profile | Risk of sexual side effects higher than with other SSRIs and SNRIs | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for PMDD, OCD, panic disorder, PTSD, social anxiety |

| Paroxetine | 10–60 mg/day | Anticholinergic effects (weight gain, sedation, constipation), gastrointestinal and sexual side effects | Risk of discontinuation syndrome‡: may require slower taper; controlled-release formulation may decrease risk of discontinuation syndrome; increased risk of drug interactions; consider for patients with coexisting depression and anxiety | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for PMDD, OCD, panic disorder, social anxiety, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD |

| Fluvoxamine | 50–300 mg/day | Anticholinergic effects (weight gain, sedation, constipation), gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, anorexia, insomnia; poor side-effect profile | May have fewer associated sexual side effects than other SSRIs and SNRIs; consider for patients with coexisting depression and anxiety; increased risk of drug interactions | FDA-approved only for OCD; off-label use for major depressive disorder |

| Citalopram | 10–40 mg/day | Gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, sedation; acceptable side-effect profile | Black-box warning regarding doses >40 mg because of QT prolongation | Major depressive disorder; off-label use for anxiety disorders |

| Escitalopram | 5–20 mg/day | Gastrointestinal and sexual side effects | May be associated with a lower risk of headache, dizziness, sedation, and gastrointestinal side effects than other SSRIs and SNRIs; S-enantiomer of citalopram | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for generalized anxiety disorder |

| SNRIs | ||||

| Venlafaxine | 37.5–225 mg/day (extended-reiease formulation) or twice daily (immediate-release formulation, sustained-release formulation) | Agitation, insomnia, tremor, hypertension, tachycardia, sweating, gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, headache, discontinuation syndrome‡: | Risk of discontinuation syndromê: may require slower taper; extended-release formulation may decrease risk of discontinuation syndrome; may increase energy; may help with anergia or attentional symptoms; risk of death from over-dose greater than with other first-line agents | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder, neuropathic pain |

| Desvenlafaxine | 50–100 mg/day | Agitation, insomnia, tremor, hypertension, tachycardia, sweating, discontinuation syndrome‡: | Primary active metabolite of venlafaxine; risk of discontinuation syndrome‡; extended-release formulation may reduce risk of discontinuation syndrome; may increase energy; may help with anergia or attentional symptoms; may need to adjust dose in patients with renal insufficiency | Major depressive disorder; off-label use for anxiety disorders |

| Duloxetine | 60 mg total/day, administered once or twice daily | Agitation, insomnia, tremor, hypertension, tachycardia, sweating | May increase energy; may help with anergia or attentional symptoms; consider for patients with coexisting pain conditions | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved for generalized anxiety disorder, diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, chronic musculoskeletal pain |

| Other agents | ||||

| Levomilnacipran | 20–120 mg/day | Agitation, sweating, hypertension, tachycardia, palpitations, dysuria | L-enantiomer of milnacipran; may increase energy; may help with anergia or attentional symptoms; fewer gastrointestinal side effects, weight gain, sedation, and sexual dysfunction than SSRIs and SNRIs | Major depressive disorder |

| Bupropion | 50–450 mg/day (extended-rei ease formulation) or twice daily (immediate-release formulation, sustained-release formulation) | Tachycardia, agitation, insomnia, seizures | Consider in combination with SSRI or SNRI; sustained-release and extended-release formulations allow for less frequent dosing and may increase adherence than immediate-re-lease formulation‡; may help with anergia or attentional symptoms; 0.4% increased risk of seizure at approved doses; contraindications include seizure disorder, bulimia or anorexia, alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal; not associated with sexual dysfunction | Major depressive disorder; also FDA-approved as aid to smoking cessation; extended-reiease formulation indicated for prophylaxis of seasonal depression; may be helpful for ADHD, attention problems, or anergia symptoms |

| Mirtazapine | 15–45 mg/day | Sedation, increased appetite, weight gain | Consider in combination with SSRI or SN Rl; consider for patients with coexisting depression and anxiety; lower dose may be more sedating; consider bedtime administration if insomnia or low appetite are present; should not be used if weight gain is an issue; associated with less sexual dysfunction than SSRIs or SNRIs and may aid in SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction | Major depressive disorder; off-label use for anxiety disorders |

| Vilazodone | 10–40 mg/day | Gastrointestinal side effects, insomnia | Associated with less sexual dysfunction than SSRIs and SNRIs; should be taken with food | Major depressive disorder |

| Vortioxetine | 10–20 mg/day | Gastrointestinal and sexual side effects, dry mouth | Effective in patients with cognitive dysfunction from major depressive disorder | Major depressive disorder, cognitive impairment (may improve processing speed) |

| Agomelatine | 25–50 mg/day | Headache, gastrointestinal side effects, fatigue, back pain, anxiety, abnormal dreams, weight gain | May help to normalize sleep cycle (melatonin agonist); increased risk (1–3%) of transaminitis; liver function should be checked at baseline, at adjustment of dose (at 3, 6, 12, and 24 wk), and thereafter when clinically indicated | Major depressive disorder; not available in United States |

ADHD denotes attention deficit-hyper activity disorder, FDA Food and Drug Administration, OCD obsessive-compulsive disorder, PMDD premenstrual dysphoric disorder, PTSD post-traumatic stress disorder, SNRI serotonin-norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitor, and SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

SSRIs may increase the risk of bleeding and should be used with caution in combination with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, aspirin, or other anticoagulants, or in patients who are at risk for bleeding.

The discontinuation syndrome may involve flulike symptoms, insomnia, nausea, imbalance, sensory disturbances, and hyperarousal.

The selection of an antidepressant is guided by adverse-effect profiles as well as by the patient’s coexisting psychiatric disorders, specific symptoms, and treatment history.43 A goal should be to minimize adverse effects, particularly those that might exacerbate existing symptoms or other medical conditions. For instance, drugs commonly associated with increased sedation (e.g., mirtazapine and paroxetine) are not administered during the day in patients with daytime fatigue; conversely, for patients with difficulty sleeping, these sedating drugs may be prescribed at bedtime to promote sleep. Patients with coexisting anxiety are often treated with SSRIs or SNRIs, whereas bupropion and levomil-nacipran are generally not used (Table 2). Treatment selection should also include consideration of the patient’s personal and family history of medication response and side effects, his or her drug preference, and cost and accessibility (i.e., insurance coverage).44

Medication trials generally begin at a low dosage, with dose adjustments typically occurring every 2 weeks. Although improvement may be noted at as early as 2 weeks, full relief of symptoms may not be seen for 8 to 12 weeks (at an adequate dosage). If the initial trial does not yield substantive improvement, switching to another first-line antidepressant (of the same or a different class) is appropriate. Psychotherapy should also be considered, since the combination of drug therapy and psychotherapy has been shown to be more effective than drug therapy alone.45 If partial improvement is noted at the maximally tolerated dose, adding an antidepressant of a different class or targeting residual symptoms with other treatments may be an appropriate next step. Psychiatric consultation is recommended if combined therapy or use of a treatment option other than first-line therapy is being considered. Once remission is achieved, maintenance antidepressant treatment to decrease the risk of relapse should generally be continued for at least 6 months.46 For persons with a high risk of relapse (e.g., two or more past episodes, residual symptoms, or a history of prolonged or severe symptoms), maintenance treatment should be considered for 2 years or more.47 Recurrence of symptoms is common after an index episode; longitudinal studies have shown recurrence rates of 26% within 1 year and 76% within 10 years.48

In general, first-line antidepressants have a manageable side-effect profile (Table 2). One potentially severe adverse effect associated with SSRIs and SNRIs is the serotonin syndrome, which is characterized by agitation, confusion, fever, and tremors that may proceed in severe cases to seizures, coma, and death. Although this syndrome is very rare, the risk may be higher when other drugs that elevate serotonergic tone (e.g., monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, tramadol, triptans, ondansetron, and metoclopramide) are used in combination with SSRIs and SNRIs.

In 2004, the FDA issued a black-box warning that all SSRIs and venlafaxine were associated with an increased risk of suicidality among persons younger than 24 years of age (www.fda.gov/ downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/InformationbyDrug Class/UCM173233.pdf). However, other independent reviews have not confirmed this associa-tion.42 Assuming that appropriate monitoring practices — including those for suicidality — are in place, the risks of untreated depression among adults of any age outweigh the risks of drug treatment.44

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Investigators have begun to identify subtypes of depression on the basis of clinical features49 or findings on functional magnetic resonance im-aging,50 as well as on the basis of genetic risk factors51 and other potential predictors of treatment response52; however, more studies are needed before specific biomarkers or predictors of response may be used to provide clinically valuable information. Pharmacogenomic testing has been suggested to guide dosing and minimize potential dose-related side effects, but evidence that this information aids in predicting treatment response or improves cost-effectiveness is lacking.53

GUIDELINES

Three treatment guidelines for depression — by the American Psychiatric Association,44 the CANMAT,54 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (United Kingdom)55 — offer similar guidance, although only the CANMAT guidelines address recent antidepressant medications. The recommendations in this article are generally concordant with these guidelines.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The patient in the vignette meets the criteria for a major depressive episode. Although her depressive symptoms are not completely debilitating, she has substantial distress that is affecting her functioning; this suggests an episode of moderate severity. We would review her medical history and medications and ask about substance use to rule out potential causes of or contributors to her depressive symptoms. A careful history is also needed to assess evidence of mania or hypomania, since treatment for bipolar depression would differ from that for major depressive disorder. She should be immediately evaluated for possible suicidality to establish that she has no active plans to harm herself and to ensure that she agrees to seek emergency treatment if such feelings develop.

Pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or both are all reasonable treatment options for moderate depression. In this patient, given that symptoms have been present for several months, we would recommend a combination of first-line pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. We would initiate sertraline, which is cost-effective and generally has an acceptable side-effect profile, starting at 50 mg daily and increasing by 50 mg every 2 weeks to a maximum dose of 200 mg, while monitoring for effectiveness and adverse effects. We would discuss effective psychotherapeutic approaches but would favor interpersonal therapy so that the patient could begin to address the relationship conflicts with her partner. If her symptoms completely remit, we would recommend that she continue the use of medication for at least 6 months before considering discontinuation.

Key Clinical Points.

DEPRESSION IN THE PRIMARY CARE SETTING

Screening for depression and suicidal thinking and behavior is important in the primary care setting.

Distinguishing between bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder is critical for treatment selection.

The first-line treatment for mild depression is psychotherapy and symptom monitoring.

Antidepressant drugs have been shown to have a favorable benefit-risk profile in moderate-to-severe depression. Psychotherapy may also be a first-line choice for moderate depression.

The choice of treatment depends on associated side effects, the presence of coexisting conditions, specific symptoms, and the patient’s history of response.

Acknowledgments

We thank the 7SE research unit and staff for their support and Ioline Henter of the National Institute of Mental Health for invaluable editorial assistance with an earlier version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Dr. Zarate reports holding patents (PCT/US2007/06898; 8,785,500; 9,539,220; and 9,592,207) on intranasal administration of ketamine to treat depression, patents (PCT/US2012/060256; 9,867,830; and 6296985) on the use of (2R, 6R)-hydroxynor-ketamine, (S)-dehydroxynorketamine, and other stereoisomeric dehydro and hydroxylated metabolites of (R,S)-ketamine in the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain, pending patent (PCT/US2017/024238) on methods of using (2R, 6R)-hydroxynor-ketamine and (2S, 6S)-hydroxynorketamine in the treatment of depression, anxiety,anhedonia, fatigue, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic stress disorder, and pending patent (PCT/ US2017/024241) on crystal forms and methods of synthesis of (2R, 6R)-hydroxynorketamine and (2S, 6S)-hydroxynorketamine.

No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen H-U. TWelvemonth and lifetime prevalence and life-time morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2012;21:169–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henriksson MM, Aro HM, Marttunen MJ, et al. Mental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150: 935–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health, United States, 2016: with chart-book on long-term trends in health. Hyatts-ville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.: DSM-V. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. The molecular neurobiology of depression. Nature 2008; 455:894–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke KC, Burke JD Jr, Regier DA, Rae DS. Age at onset of selected mental disorders in five community populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1990;47:511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton WW, Anthony JC, Gallo J, et al. Natural history of diagnostic interview schedule/DSM-IV major depression: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:993–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003;289:3095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 1996;276:293–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fava M, Rush AJ, Alpert JE, et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:342–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank RG, Huskamp HA, Pincus HA. Aligning incentives in the treatment of depression in primary care with evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Serv 2003;54: 682–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M ark TL, Levit KR, Buck JA. Data-points: psychotropic drug prescriptions by medical specialty. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60:1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmedani BK, Stewart C, Simon GE, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in health care visits made before suicide attempt across the United States. Med Care 2015; 53:430–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sartorius N Stigma and mental health. Lancet 2007;370:810–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.A follow-up report on preventing suicide: focus on medical/surgical units and the emergency department. Sentinel Event Alert 2010;46:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Crengle S, et al. Validation of PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to screen for major depression in the primary care population. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horowitz LM, Snyder D, Ludi E, et al. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions to everyone in medical settings: the asQ’em Quality Improvement Project. Psychosomatics 2013;54:239–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiao B, Rosen Z, Bellanger M, Belkin G, Muennig P. The cost-effectiveness of PHQ screening and collaborative care for depression in New York City. PLoS One 2017; 12(8):e0184210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denchev P, Pearson JL, Allen MH, et al. Modeling the cost-effectiveness of interventions to reduce suicide risk among hospital emergency department patients. Psychiatr Serv 2018;69:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cassem NH, Papakostas GI, Fava M, Stern TA. Mood-disorder patients In: Stern TA, Cassem NH, Fricchione G, Rosenbaum JF, Jellinek M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004:69–92. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassem NH, Murray GB, Lafayette JM, Stern TA. Delirious patients In: Stern TA, Cassem NH, Fricchione G, Rosenbaum JF, Jellinek M, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital handbook of general hospital psychiatry. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby, 2004:119–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers D, Pies R. General medical with depression drugs associated. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2008;5:28–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson JR. Major depressive disorder treatment guidelines in America and Europe. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:Suppl E1:e04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thase ME, Greenhouse JB, Frank E, et al. Treatment of major depression with psychotherapy or psychotherapy-pharmaco-therapy combinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:1009–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G, van Oppen P. Psychotherapy for depression in adults: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:909–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Weitz E, An-dersson G, Hollon SD, van Straten A. The effects of psychotherapies for major depression in adults on remission, recovery and improvement: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2014;159:118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A metaanalysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2013;58:376–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, Huibers MJ. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry 2016;15:245–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Oper-skalski B, Von Korff M. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;292:935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnberg FK, Linton SJ, Hultcrantz M, Heintz E, Jonsson U. Internet-delivered psychological treatments for mood and anxiety disorders: a systematic review of their efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. PLoS One 2014;9(5):e98118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirsch I, Deacon BJ, Huedo-Medina TB, Scoboria A, Moore TJ, Johnson BT. Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: a meta-analysis of data submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 2008;5(2):e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA 2010;303:47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1905–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Rush AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:1439–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuro-psychopharmacology 2012;37:851–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saveanu R, Etkin A, Duchemin AM, et al. The international Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D): outcomes from the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatr Res 2015;61:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018;391:1357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder. Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry 2016;61:540–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmerman M, Posternak M, Friedman M, et al. Which factors influence psychiatrists’ selection of antidepressants? Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:1285–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.APA Work Group on Psychiatric Evaluation. The American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the psychiatric evaluation of adults. 3rd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, Anders-son G. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2009;70:1219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baldessarini RJ, Lau WK, Sim J, Sum MY, Sim K. Duration of initial antidepressant treatment and subsequent relapse of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35:75–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Grigoriadis S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. III. Pharmacotherapy. J Affect Disord 2009;117:Suppl 1: S26–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Outcome of depression in psychiatric settings. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arnow BA, Blasey C, Williams LM, et al. Depression subtypes in predicting antidepressant response: a report from the iSPOT-D trial. Am J Psychiatry 2015;172: 743–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat Med 2017;23:28–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet 2018;50:668–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green E, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Schatzberg AF, Rush AJ, Ma J, Williams L. Personalizing antidepressant choice by sex, body mass index, and symptoms profile: an iSPOT-D report. Pers Med Psychiatry 2017;1–2:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenblat JD, Lee Y, McIntyre RS. Does pharmacogenomic testing improve clinical outcomes for major depressive disorder? A systematic review of clinical trials and cost-effectiveness studies. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78:720–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam RW, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, MacQueen GM, Milev RV, Ravindran AV. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: introduction and methods. Can J Psychiatry 2016;61: 506–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management 2009. October 2009. (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90). [PubMed]