Objective

The aim of the study was to determine (1) whether do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders created upon hospital admission or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) are consistent patient preferences for treatment and (2) patient/health care agent (HCA) awareness and agreement of these orders.

Methods

We identified patients with DNR and/or POLST orders after hospital admission from September 1, 2017, to September 30, 2018, documented demographics, relevant medical information, evaluated frailty, and interviewed the patient and when indicated the HCA.

Results

Of 114 eligible cases, 101 met inclusion criteria. Patients on average were 76 years old, 55% were female, and most white (85%). Physicians (85%) commonly created the orders. A living will was present in the record for 22% of cases and a POLST in 8%. The median frailty score of “4” (interquartile range = 2.5) suggested patients who require minimal assistance. Thirty percent of patients requested cardiopulmonary resuscitation and 63% wanted a trial attempt of aggressive treatment if in improvement is deemed likely. In 25% of the cases, patients/HCAs were unaware of the DNR order, 50% were unsure of their prognosis, and another 40% felt their condition was not terminal. Overall, 44% of the time, the existing DNR, and POLST were discordant with patient wishes and 38% were rescinded. Of the 6% not rescinded, further clarifications were required. Discordant orders were associated with younger, slightly less-frail patients.

Conclusions

Do-not-resuscitate and POLST orders can often be inaccurate, undisclosed, and discordant with patient wishes for medical care. Patient safety and quality initiatives should be adopted to prevent medical errors.

Key Words: DNR, POLST, POLST like, end of life, living will, advance care planning

End-of-life (EOL) care for the older people and those with a terminal diagnosis is costly. The Centers for Medicare Services indicate that one-fourth of all Medicare expenditures are spent in the last year of life.1 The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released a ground-breaking report indicating that EOL care is broken and spending was predicted to exceed 350 billion by 2019.2 More recently, in a new study, Einav et al3 reported that EOL spending is overestimated and patients with the highest 1-year mortality risk account for less than 5% of spending. Reaction to the IOM report led to aggressive EOL planning initiatives across many healthcare systems that have impacted many patients and resulted in both over and undertreatment of patients.4,5

Cost aside, ensuring that patient preferences are honored should be the primary focus of advance care planning. The goal should be the accurate representation of patients' wishes when healthy, when critically ill, or at EOL. The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 was enacted to allow documentation of patient wishes, most commonly the living will (LW), for resuscitation and life support before incapacitance.6 In an attempt to ensure portability of patient wishes, the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) was promulgated throughout Oregon in the 1990s,7 representing an actionable set of medical orders for care. This led to the creation of the National POLST Paradigm, which is now approved or operationalized very quickly in some form in all 50 states.8 Of concern, the Oregon POLST process, which began the National POLST, has now withdrawn from the National POLST Paradigm in 2017, citing concerns of conflicts of interest, and now operates as the Oregon POLST.8,9 The acronym used by states participating in the National POLST can vary (MOST, MOLST, POLST) as can the content, color, and format of the forms. These variations were deployed but never evaluated to ensure patient safety. Either LW or POLST, health care providers must understand the documents and know how and when to implement them to ensure patient preferences.

The Realistic Interpretation of Advance Directives (TRIAD) research suggests that neither LWs nor POLST is fully understood. Living wills have often been construed as do not resuscitate (DNR).10–13 The POLST forms can be confusing, resulting in patient deaths or overresuscitations.4,5,12,13 The incomplete POLST forms added further confusion resulting in over resuscitations when at EOL.14 Despite these shortcomings, several studies have indicated conformance between the POLST form content, patient treatment, and patient outcomes.15–17 Importantly, patient assent/consent for treatment, however, was not demonstrated in these studies and at least one study suggests discordance between what was documented on the POLST versus what the patient actually consented.18 Thus, it still remains unclear whether LWs and POLST documents unambiguously represent EOL patient preferences.

Recently, research has been published to suggest process improvements, such as interviewing patients with no code status documentation or a full code status choice upon hospital admission, and then deploying targeted EOL education to those patients. The result was creation of DNR orders or having changed full-code orders to DNR orders after interventions.19 Additional research has been directed to study code status transition from full code to DNR.20 These studies did not included patients with existing DNR orders or the reversal of DNR to Full Code Orders.

The present study seeks to expand upon prior EOL research. We sought to identify patients with a DNR order created upon admission to our institution and then directly interview them (or their health care agents [HCAs]) to determine their preferences. Specific aims include the following: (a) assess patient EOL resuscitation and treatment preferences based on patient or family member interview; (b) assess the level of patient debility; (c) determine whether a conflict existed between patient interview responses versus content of medical record (e.g., DNR or POLST); (d) resolve or rectify any obvious conflict between documentation and patient wishes; and (e) assess the level of patient debility.

METHODS

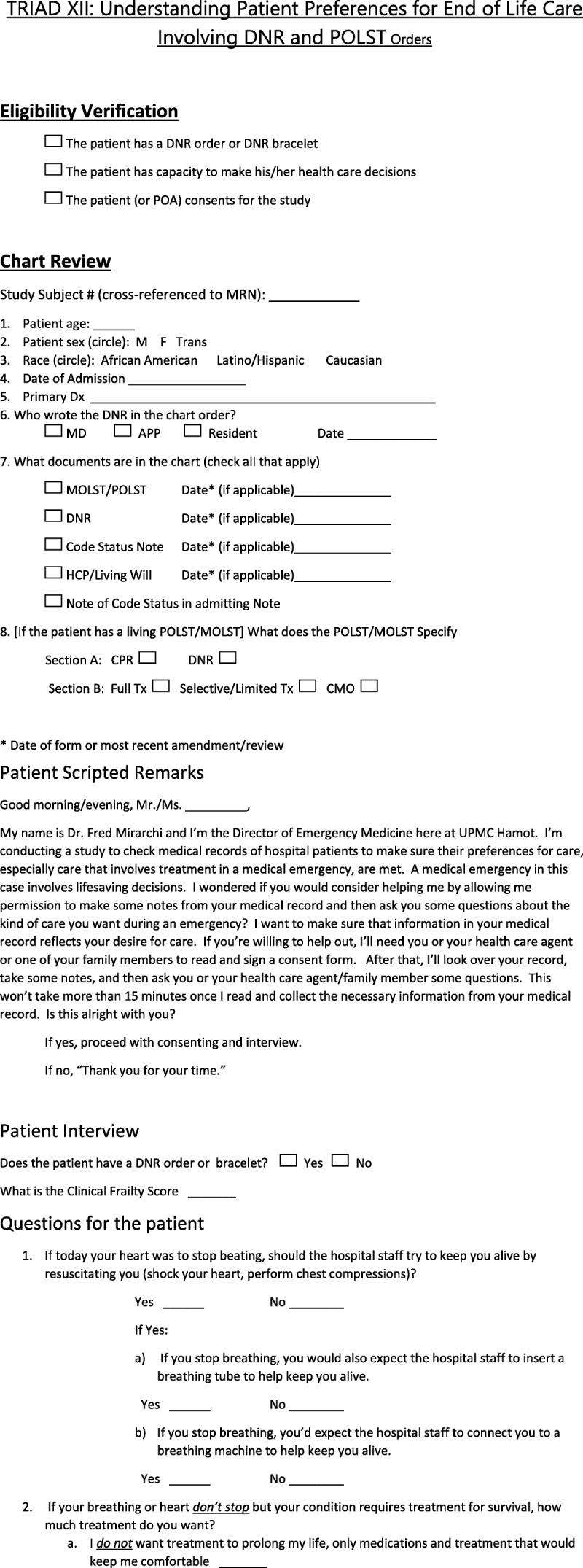

This was an institutionalized review board–approved, prospective, single-center study of in-hospital patients with existing DNR or POLST orders. Patient electronic records were queried for active DNR orders using a report function that identifies DNR orders on all admitted patients for the date queried. Dates of study enrollment were from September 1, 2017, to September 30, 2018, to allow sufficient enrollment and provide time-relevant (e.g, current hospital enrollment) information. Once identified, patients (or appointed HCA) who agreed to the use of their medical information in a deidentified manner were asked to sign a study consent. To minimize variability, the survey was administered by a trained group existing of primary and co-investigators. Patients were assigned a study number based on chronology of entry into the study. Study number and the patient's medical record number were recorded on a data collection form. Data obtained from both the electronic medical record (EMR), including diagnosis, represented retrospective data collection. However, information derived from the patent interview was obtained prospectively. All data were recorded on the data collection form. Information from these forms was then abstracted into an electronic spreadsheet and contained the patient's study number to ensure confidentiality. Data forms were secured in the principal investigator's office. The medical records of patients with DNR orders were then then reviewed for evidence of LW and/or POLST document and information abstracted onto the data collection form (Fig. 1). Information abstracted included date of admission, age, sex, race, primary diagnosis, and the medical provider who prescribed the DNR order.

FIGURE 1.

TRIAD DNR safety audit tool.

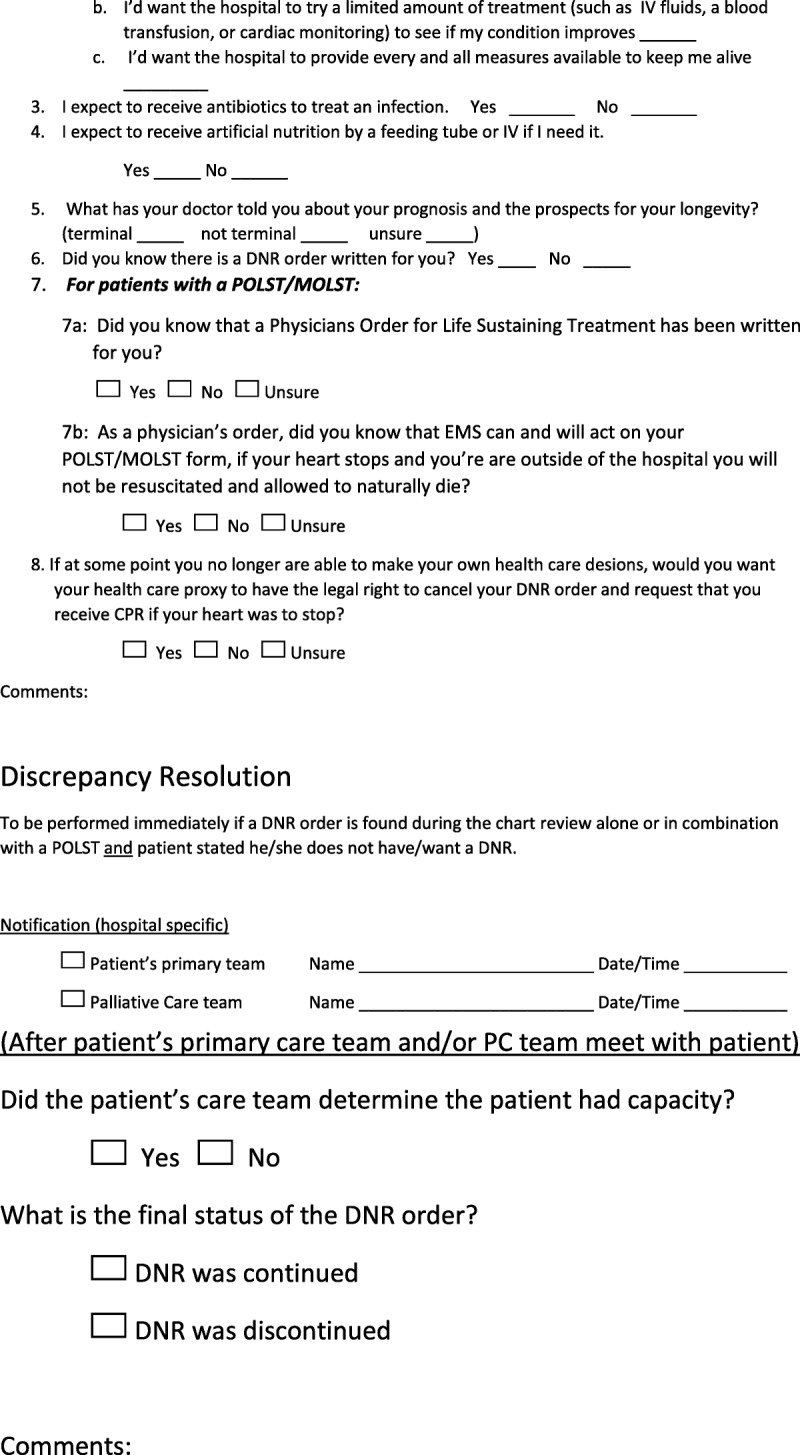

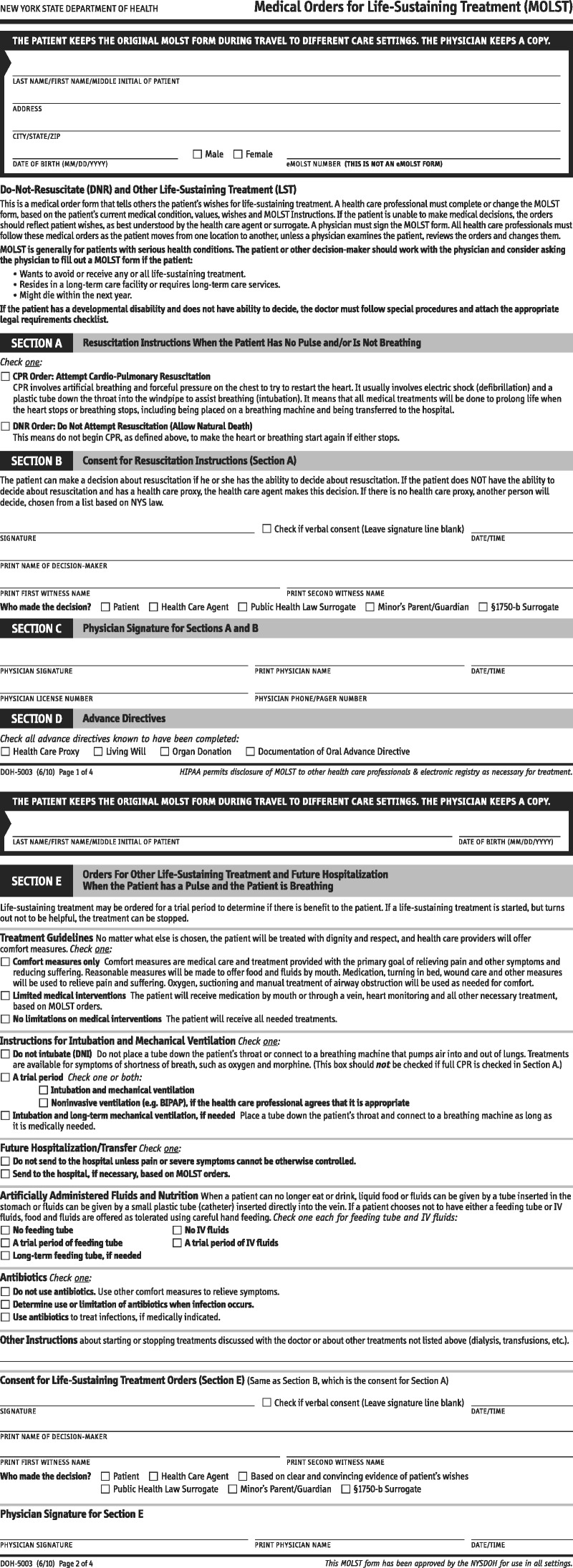

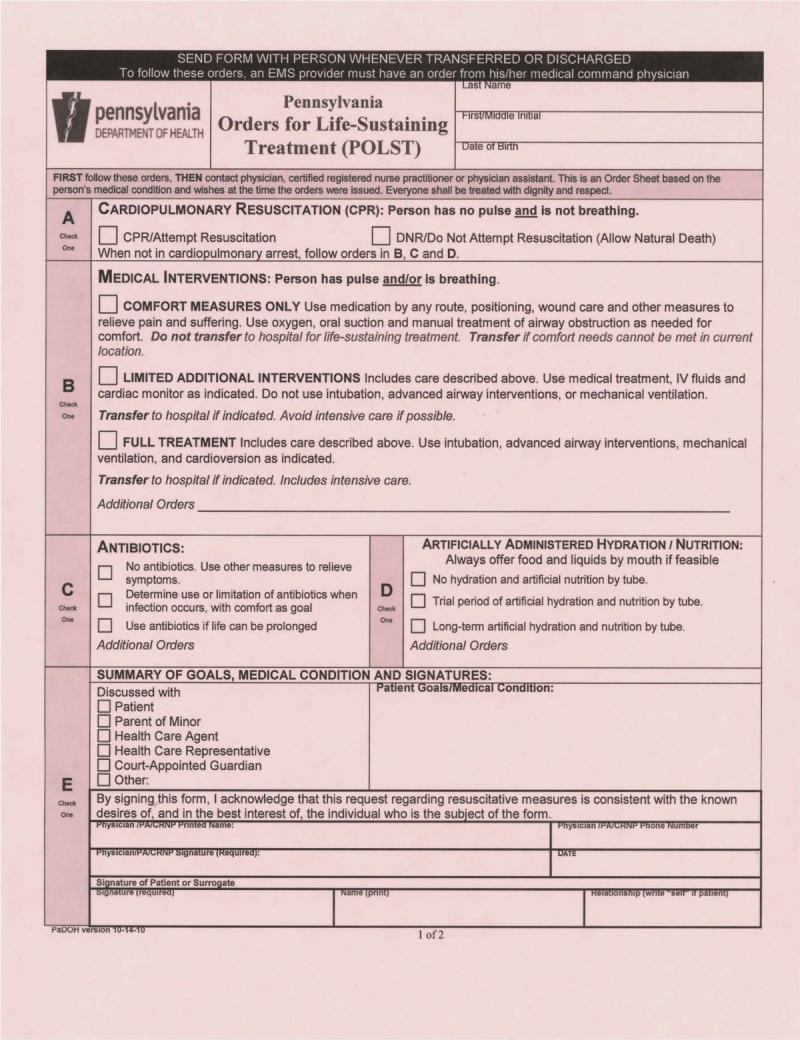

Patients with capacity or HCA's who consented were interviewed by one of the investigators to determine their knowledge and awareness of DNR orders (hospital DNR or POLST). All interviews took place during current hospitalization with the majority occurring within the first 48 hours of admission. Patients or HCA's were asked about the patient's prognosis (awareness of presence or absence of a terminal condition), awareness of the DNR order, and understanding of treatment selection listed in the POLST or LW (Figs. 2–4). Additional queries addressed their preference for resuscitation and supportive medical care and treatment (Fig. 1) and have a direct correlation to a DNR or POLST content. Overt discrepancies between information contained in medical record documentation and patient preferences, if identified, were reported to the attending physician to be immediately reconciled.

FIGURE 2.

Living will document.

FIGURE 4.

MOLST document.

FIGURE 3.

POLST document.

Given that patient debilitation may have an impact on assigning either a DNR order or POLST, patients were assessed for “frailty” based on an established, validated clinical scoring algorithm. In the case of POLST orders, in particular, frailty represents a precondition for enacting the order.21 In many cases, frailty represents a purely subjective determination by the clinician, who may or may not be factual. Ultimately, our intent was to determine how debilitated and frail study patients were. Scores were generated by the interviewers and used as an outcome measure rather than a demographic to determine the relevance of frailty to EOL orders.

Data analysis consisted of establishing the rates of discrepancy, changes from DNR to full code (reinstatement of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), change to medical support measures) and preferences for care. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were assigned to percentages. Subgroup analysis examined demographic and admission factors for their impact on discrepancy. Scale factors were analyzed with either a t test or a Mann-Whitney U test, based on data normality. χ2 test or Fisher exact test was used for rates. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

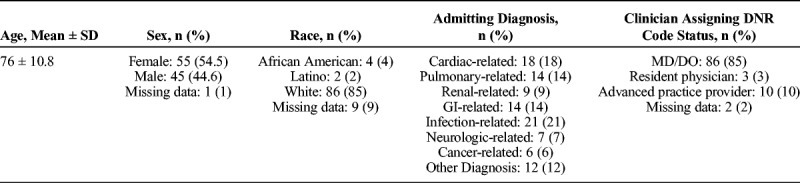

Of 114 eligible patients, data for 101 were usable and included in the analysis. The 13 exclusions had incomplete information (survey document not fully completed or withdrew before interview completed) or issues pertinent to consenting (investigator did not capture signature). The mean ± SD age of the patients included was 76 ± 10.8 years (Table 1). Slightly more than half (55%) were female and the majority (85%) were white. The most common admission diagnosis was related to an infection (21%), followed by cardiac (18%), pulmonary (14%), and gastrointestinal-related (14%) issues. All had DNR orders documented in their chart. Physicians (85%) most commonly assigned DNR status. Along with DNR designation, 84% of patient charts contained a notation that expounded on the order. An LW was present for 22% and a POLST for 8%. For POLST patients, all had a DNR in Box A and five stipulated limited treatment and three stipulated comfort measures only.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Admission Information

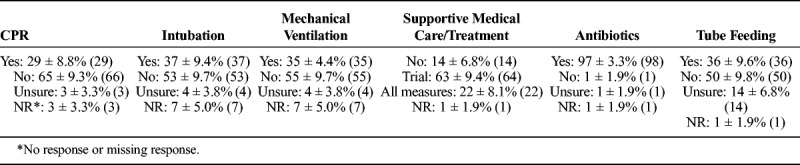

The patient interview revealed a median frailty score of 4 (range = 0–8; interquartile range = 2.5). Most patients declined CPR but 30% requested CPR (Table 2). Although approximately half of the patients refused intubation, mechanical ventilation, or tube feeding, more than 30% requested it. Most patients with a DNR (63%) wanted a trial of medical support (even if aggressive) to see whether improvement occurs. Similarly, most patients (98%) would want antibiotics if warranted.

TABLE 2.

Preferences for EOL Care Based on Patient Interview “Do you (patient) want…?”

Patients often were not aware of either the DNR order or their medical prognosis. For patients responding to the question, 25% (±8.4% CI) indicated that they were unaware of the order. Most patients (50%, ±9.8% CI) were unsure of their prognosis and another 40% (±9.6% CI) felt that their condition was not terminal at the time of admission.

With respect to discordant orders, for all patients, 44% (±9.7% CI) of their EOL wishes were at odds with the existing DNR order, and in 38% (±9.5% CI), the DNR order was rescinded. For the six patients who had a discrepancy that did not result in overturning the DNR, further clarification of EOL care was required. For patients without a POLST, rates were similar. Discrepancy was noted in 41% (±10.0% CI) with the order rescinded in 37% (±9.8% CI). However, discrepancy was higher in patients with a POLST. For the eight patients with a POLST, the discrepancy rate was 75% and the order rescinded in half (50%). Most patients (84%, ±7.1% CI) were considered mentally competent and had capacity for decision-making. For 12%, the HCA responses (response missing for 4% of cases).

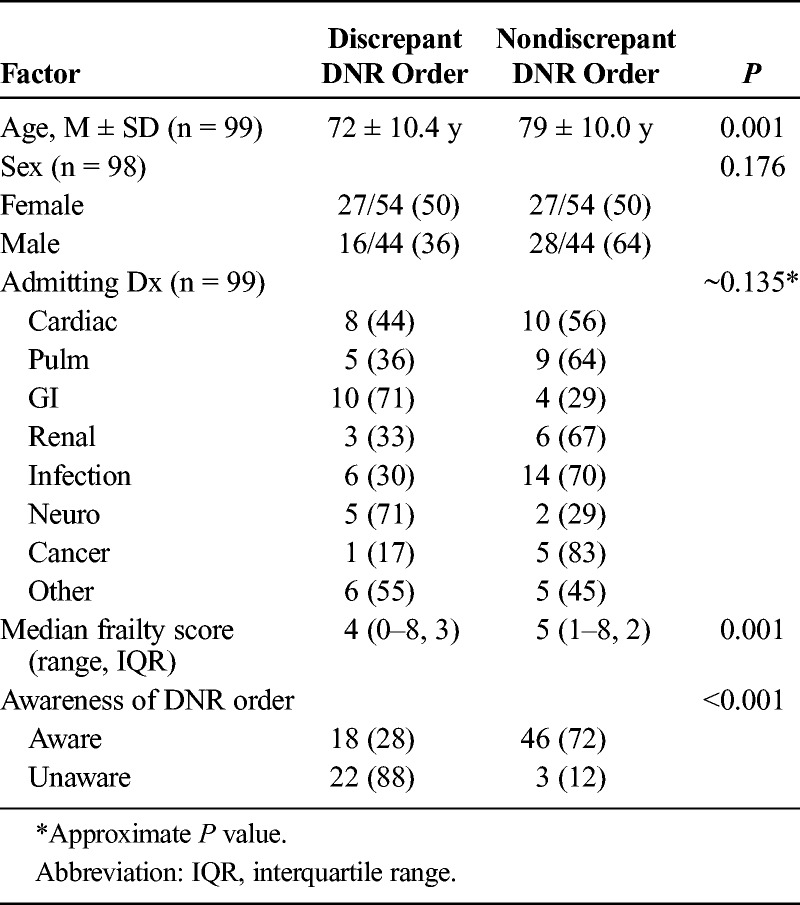

Subgroup Analysis

Age was a factor in discrepancy. Patients with EOL discrepancies were, on average, 7 years younger than patients without a discrepancy (P = 0.0012) (Table 3). Admitting diagnosis may also be related to inappropriate DNR orders. Both gastrointestinal- and neuro-related admissions had inordinately high discrepancy rates, although small subgroups militated against statistical power (P = 0.135). Frailty score was also significantly different between groups. The median score for patients with discrepancy was a point lower than those without a discrepancy (P = 0.001). Finally, patients' awareness of the DNR order was a factor in discrepancy. Discrepancy rates were approximately 60% higher in patients who were not aware of the order (P < 0.001).

TABLE 3.

Subgroup Analysis: Factors Affecting Discrepancy

DISCUSSION

More than half of elderly patients will visit an emergency department in the last month of life.8,22 Moreover, 50% will not be able to participate in the decision-making process when at EOL.2,8 However, when the patient enters a healthcare facility, they are often asked two questions: “Do you have a living will?” and “How do you want to be treated if you experience cardiac arrest?” Answers to these questions get documented in the form of code status for resuscitation and go unchecked as far as quality oversight. In the present study, we found significant amounts of discordance between what was documented in the medical records and what the patients understood and agreed to, with an approximate discordance rate of 30% to 40%. For patients with POLST documents, this rate was higher. Medical record inaccuracy related to code status is not new and was effectively reported by Bischoff et al.19 Furthermore, previous research supports discordant rates (30%–50%) of what was documented on a POLST versus patient informed consent.18

Generation of a DNR order carries with it the sense of patient frailty or near-terminal condition. To examine this objective and to eliminate patient bias, investigators, who directly interviewed the patient, calculated the frailty score, which is a validated tool used by clinicians to assess baseline function and daily activities. Frailty is one of the determinants for issuing a POLST.21 Patients in this study had a median score of 4, indicating independence but requiring some degree of assistance with daily activities. If a DNR order or POLST is appropriate for extremely frail patients, then this cohort failed to show evidence of this. Furthermore, patients with a discrepancy were less frail (lower frailty score) than those who did not have a discrepancy. Overall, DNR orders were assigned to patients who were not especially debilitated.

Clear patient communication is an absolute imperative for safe advance care planning (ACP) and EOL care. As previously noted, LW and POLST documents can be frequently misinterpreted. Zive et al23 recently evaluated two cohorts of the POLST registry. Their conclusions suggested a need to test new criteria for POLST completion and that utilizing POLST in nonterminal patients can induce greater potential for patient harm. Therefore, regardless of use of POLST, LW, or newer technology of Scripted Patient to Clinician Video, reaffirming patient wishes during hospital admission should be standard practice. Previous research suggested the use of a safety checklist13,24 (Fig. 5) to ensure affirmation of patient wishes. However, Abbot8 reports lack of adoption and for no apparent reason. A reason could be that there is belief in practice that once a patient has decided to be a DNR, the conversation should not be entertained again. Our data urge caution with this practice because the error rates are high and could have affected the safety and well-being of patients while hospitalized for aggressive treatment.

FIGURE 5.

Resuscitation pause checklist.24

Discussions about EOL care are admittedly difficult. It has often been said that physicians do not want to or are uncomfortable having the discussions. However, our experience was that the patients themselves did not mind the discussion. In our study, there were very few patients who became upset with another conversation about EOL preferences. These patients were quickly assured that the intent was to ensure fidelity to their wishes. There were also patients who were quite upset to find that they had a DNR order in their records without their knowledge and felt that it did not reflect their current wishes. Furthermore, most patients with a discrepancy were unaware of the order. In interviews involving HCA's, the questionnaire either caused decision-makers the chance to reaffirm their DNR decisions or raised more questions. Almost universally, patients wanted a trial of medical support along with antibiotics if warranted. In one instance, an HCA (who is an attorney) clearly stated that he did not know his family that a member had a POLST document. There were also incidences where clarifications were required with interventional specialties. For example, a cardiology service refused to perform a therapeutic procedure because of the DNR order.

Revalidating patient EOL care preferences at hospital admission can help circumvent the propagation of incorrect treatment.25 Erroneous information about EOL care is often entered into the EMR. This information is referenced during future hospitalizations and can have life-ending impact on the patients care when critically ill and seeking aggressive medical care. The EMR at present lacks the quality oversight to evaluate the DNR (or variations of DNR orders such as with the POLST order) at the time of creation. Healthcare systems lack the quality oversight to ensure the medical provider who then comes in contact with that order is competent to use that order in a safe and effective manner for the patient. Here again, a simple patient safety checklist can be adopted to ensure appropriate treatment.8 A more novel approach would be to use scripted patient to clinician video and empower both patients and HCA's to prevent the medical error before it starts.12,25 With the approval of ACP codes for medical provider reimbursement, there is now an opportunity to formalize the structure of the conversation and to check and verify that the orders are created appropriately and correctly. Because EOL care and critical illness are not always the same,26 systems nationwide should evaluate their existing policies and procedures to ensure that we capture this vital information to ensure the safety of both the healthy as well as terminally ill patient navigating the system.

One of the study limitations is that this was a single-center convenience sample. Sampling bias was introduced because we only evaluated patients with a DNR or POLST order. Responses of the patient or HCA during the interview could have been influenced by differences in personality nuances of the investigators, despite an in-service that was provided before investigator involvement. Although survey content validity was established via peer review, reliability was not assessed. Documents (POLST and LW) also pose a possible limitation because these documents may or may not have been completed properly before admission; this could have led to increased patient, HCA, and provider confusion. Another limitation of this study is the timing of the interview from when the DNR order was written to when the patient or agent was interviewed. The DNR orders were created upon hospital admission. As previously noted, all interviews occurred during current hospitalization. Although most interviews occurred within the first 48 hours of the hospitalization, bias could conceivably be introduced if patients or agents were interviewed with longer hospitalizations. Lastly, study power, especially in the context of subgroup comparisons, was limited by a small sample size.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data herein call for further research in the approach to ACP for the healthy and EOL patient. Systems must check and verify existing DNR and POLST orders. In our research, existing DNR and POLST orders are associated with lack of informed consent, patient or HCA awareness, and have high rates of discordance. Our data further support that we must improve upon or set new standards to ensure the safety of patients traversing the healthcare system are safe, informed, and empowered to make decisions. Physicians Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment, deployed nationally very quickly, has patient safety concerns and is in flux. Living wills have been consistently misinterpreted as DNR orders. Do-not-resuscitate orders have been implicated in patient safety medical errors for well more than three decades. We extend a call for quality oversight and new process changes to incorporate approaches to better educate users of the healthcare system with information to prevent the errors before they start. A how to navigational approach combined with scripted patient to clinician video as well as an DNR order verification tool (such as used in this study) can mitigate many medical errors and ensure adequate treatment for patients with many benefits to the healthcare system as a whole.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calfo S, Smith J, Zezza M. Last Year of Life Study. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/downloads/Last_Year_of_Life.pdf. Accessed February 17, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. September 17, 2014. Available at: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-Preferences-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx. Accessed January 3, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Einav L, Finkelstein A, Mullainathan S, et al. Predictive modeling of U.S. health care spending in late life. Science. 2018;360:1462–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith E. Grieving daughter's ‘do not resuscitate’ nightmare. Boston Herald, January 28, 2016. Available at: http://www.bostonherald.com/news/local_coverage/2016/01/grieving_daughters_do_not_resuscitate_nightmare. Accessed January 28, 2016.

- 5.Kaplan A. A hospital gets sued for keeping a patent alive. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/881185. Accessed December 6, 2018.

- 6.La Puma J, Orentlicher D, Moss RJ. Advance directives on admission. Clinical implications and analysis of the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990. JAMA. 1991;266:402–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn PM, Schmidt TA, Carley MM, et al. A method to communicate patient preferences about medically indicated life-sustaining treatment in the out-of-hospital setting. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott J. The POLST Paradox: opportunities and challenges in honoring patient end-of-life wishes in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oregon POLST Coalition Reaffirms Values Avoiding Conflicts of Interest. Available at: https://oregonpolst.org/2017-coalition-reaffirms-coi/. Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 10.Mirarchi FM, Hite LA, Cooney TE, et al. TRIAD I – the realistic interpretation of advanced directives. J Patient Saf. 2008;4:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirarchi FL, Costello E, Puller J, et al. TRIAD III: nationwide assessment of living wills and do not resuscitate orders. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirarchi FL, Cooney TE, Venkat A, et al. TRIAD VIII: nationwide multicenter evaluation to determine whether patient video testimonials can safely help ensure appropriate critical versus end-of-life care. J Patient Saf. 2017;13:51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirarchi FL, Cammarata C, Zerkle SW, et al. TRIAD VII: do prehospital providers understand Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment documents? J Patient Saf. 2015;11:9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemency B, Cordes CC, Lindstrom HA, et al. Decisions by default: incomplete and contradictory MOLST in emergency care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson DK, Fromme E, Zive D, et al. Concordance of out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest resuscitation with documented end-of-life choices in Oregon. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, et al. POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:240–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2091–2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hickman SE, Hammes BJ, Torke AM, et al. The quality of physician orders for life-sustaining treatment decisions: a pilot study. J Palliat Med. 2017;20:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bischoff K, O'Riordan DL, Marks AK, et al. Care planning for inpatients referred for palliative care consultation. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Jawahri A, Lau-Min K, Nipp RD, et al. Processes of code status transitions in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:4895–4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.POLST Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ). Available at: http://www.polst.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/2016.04.03-POLST-FAQs.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018. [PubMed]

- 22.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zive DM, Jimenez VM, Fromme EK, et al. Changes over time in the oregon physicians orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: a study of two decedent cohorts. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:500–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirarchi FL, Doshi AA, Zerkle SW, et al. TRIAD VI: how well do emergency physicians understand Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) forms? J Patient Saf. 2015;11:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman RM, Mirarchi FL. Empowering patients and agents to help prevent errors with living wills, DNRs, and POLSTs. PA-PSRS Patient Saf Advis. 2018;15 Available at: https://psnet.ahrq.gov/resources/resource/32014/Empowering-patients-and-agents-to-help-prevent-errors-with-living-wills-DNRs-and-POLSTs. Accessed July 18, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirarchi FL, Yealy DM. Lessons learned from the TRIAD research opportunities to improve patient safety in emergency care near end of life. J Patient Saf. 2018; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]