Abstract

Objectives:

Successful human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccine delivery depends heavily on parents’ attitudes, perceptions, and willingness to have their children vaccinated. In this study, we assessed parental knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the HPV vaccine, and examine factors associated with willingness to have eligible children receive HPV vaccination.

Methods:

From a community health center serving Chinese members in the Greater Philadelphia area, 110 Chinese-American parents with at least one child aged 11 to 18 who had not received HPV vaccine were recruited. Data were collected in face-to-face interviews.

Results:

Chinese-American parents generally lacked knowledge on HPV and the HPV vaccine, yet had a moderately high level of intention to vaccinate their children against HPV. Ordinal logistic regression results indicated that knowledge, whether or not to involve children, doctor influence, and time lived in the United States were significantly and independently related to parental intention to have their children vaccinated against HPV.

Conclusion:

Interventions should make efforts to raise awareness of HPV and promote vaccination in doctors’ offices. The lower level of parental intention among relatively recent immigrants indicated the necessity to target this population in public health campaigns and intervention efforts.

Keywords: HPV vaccine, parental intention, knowledge, decision making, Chinese Americans, ordinal logistic regression

Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States (US) and is one of the fastest spreading diseases, with 79 million people currently infected and 14 million new cases each year.1 About 74% of new HPV cases occur in the 15–24 age group.2 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that the prevalence of any genital HPV among adults aged 18–59 is 42.5% in the total population, 45.2% among men, and 39.9% among women.3 The overall annual direct medical cost burden of preventing and treating HPV-associated disease is estimated to be $8 billion in the US.4 So far, more than 200 HPV types have been identified.5,6 Low-risk types such as 6 and 11 are responsible for about 90% of genital warts,7 whereas high-risk types such as types 16 and 18 account for about two-thirds of cervical cancers.7 Nearly all cases of cervical cancer are attributable to high-risk HPV types.8,9 HPV also can cause many other cancers, such as cancers of the anus, penis, vagina, vulva, and oropharynx.10

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine targets HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18.6 It was licensed in the US in 2006 for females11 and 2009 for males.12 Widespread use of these vaccines could prevent up to 70% of cervical cancers.13 CDC has recommended for routine vaccination at age 11 or 12 years, and vaccination can be started at age 9. Two doses of HPV vaccine (6–12 months apart) are recommended for most persons starting the series before their 15th birthday, while 3 doses (0, 1–2, and 6 months) are recommended for teens and young adults who start the series at ages 15 through 26 years, and for immunocompromised persons.14 Since the vaccine has been in use, infections with HPV types that cause most HPV cancers and genital warts have dropped 71% among teenage girls and 61% among young adult women, according to CDC estimates.15

Given the recommended age for HPV vaccine administration, parental consent is required for the vaccination of minors; therefore, parents play an active role in vaccination uptake. Successful HPV vaccine deliverance depends heavily on parental attitude and perception. Given its relatively recent history, HPV vaccination is still not well known or understood by the public. The general lack of understanding towards the vaccination, which affects people’s attitude and perception, has been cited as a prevalent issue in lowered vaccine uptake.16,17 The lack of understanding manifests in a lack of awareness of the virus, its prevalence and the relationship with cervical cancer,18 concerns over vaccine safety and general mistrust of medical and pharmaceutical agents,16,19 and concern about the possibility of the vaccine leading young females to initiate sexual intercourse earlier or to engage in risky sexual behavior.20,21

A previous qualitative study examining focus group responses among white, black and Hispanic parents suggests that insufficient information regarding the vaccine may hinder parents’ ability to make an educated decision on whether or not to vaccinate their children. Moreover, the lack of information might also lead to concerns over vaccine safety and general mistrust of medical and pharmaceutical agents, which impacted on parents’ willingness to follow through with the vaccination.16 Previous studies also suggested that parents are concerned about the possibility of the vaccine leading young females to initiate sexual intercourse earlier or to engage in risky sexual behavior.20,21 In addition, a previous study reported an increased odds of HPV vaccine awareness among “female parents and parents of female children,” and those with higher educational attainment as well as higher incomes. Time living in the US was associated with decreased odds of HPV vaccine awareness. Awareness progressively declined as the number of years living in the US decreased. There were no differences in the odds for HPV vaccine awareness based on parental age. However, lower awareness of the HPV vaccine may hinder the likelihood of the uptake of the HPV vaccine.22 Constituting 5.6% of the total American population as reported by the 2010 Census, the Asian-American population has become an increasingly prevalent racial group in the US within the last several decades and is projected to comprise 10% of the total US population by 2050.23 Among Asian-American adults aged 18–69, the prevalence of any oral HPV was 2.9% overall with 4.3% among men and 1.8% among women. For any genital HPV, the prevalence was 23.8% overall with 24.4% among men and 23.2% among women.3 Moreover, the incidence rate for HPV-related cancers was 7.5 cases per 100,000 persons for females and 2.8 cases per 100,000 persons for males. CDC estimates that about 6 Asian/Pacific Islander women are diagnosed with HPV-associated cervical cancer per 100,000 women.24 Whereas incidence rates vary significantly among Asian ethnic groups, data from the SEER registry show an incidence rate of 5.8 per 100,000 among Chinese-American women,25 comparable to the overall rate in Asian Americans. Although the rates among Asian Americans are modest when compared to national averages, there is little published information addressing HPV vaccination among Chinese-American adolescents. Understanding factors that influence parental decision-making about vaccinating their children may improve HPV vaccination uptake. For this study, we used the baseline data of a community-based HPV vaccination intervention for an underserved Chinese-American community in Greater Philadelphia to examine HPV vaccine-related knowledge, the decision-making process, and intention of Chinese-American parents or guardians towards HPV vaccination for their children.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

A total of 110 participants, specifically self-identified Chinese-American parents or legal guardians were recruited from a community health center serving Chinese-American members in the Greater Philadelphia area. Members of this community health center are primarily low-income Chinese-American or other Asian community members residing in Greater Philadelphia and southern New Jersey areas. The inclusion criteria included: (1) being self-identified Chinese-American parents or legal guardians living together with children, and (2) having at least one child aged 11–18 years old who had not received any doses of the HPV vaccine.

Planning meetings were conducted with community health center leaders and staff. Leaders and staff of the collaborating partner organization received training provided by the research team about the purpose, procedures and participant recruitment of this study. A culturally-tailored bilingual recruitment flyer was used to facilitate recruitment. The flyer was jointly developed by researchers and the community health center partner.

Data Collection

We used a cross-sectional study method to gather information on Chinese-American parents/guardians’ knowledge, attitudes about HPV, and decision-making process regarding HPV vaccination. We developed a 38-item questionnaire that included demographic measures, healthcare service accessibility, knowledge of and perception about the HPV vaccine, and the decision-making process and intention towards children’s HPV vaccination. The survey tool was pilot-tested by an expert panel consisting of public health specialists, collaborating community leaders, and academic professionals for face validity and comprehension prior to the formal study.

We collected data at the collaborating partner facility. Study participants were given the option of responding to the questionnaire in the English or Chinese languages. Onsite bilingual language assistance was provided as needed. To ensure consistent administration during data collection, we provided training to all data collection administrators and onsite bilingual translators. Questionnaire administration took approximately 20 minutes.

Measurement

Demographic information.

This information included participants’ age in years, marital status, educational level, household income, years lived in the US, children’s sex, children’s age in years, and the number of children living together.

Healthcare service accessibility.

Accessibility measures included information about children’s health insurance and regular access to a pediatrician.

Parental intention for children HPV vaccination.

We assessed parental intention with the question: “How likely [is it that] you are going to vaccinate your children?” Response options included 0 “definitely not,” 1 “probably not,” 2 “probably will,” and 3 “definitely will.”

Participants’ knowledge on HPV and HPV vaccine.

We assessed knowledge with 7 statements with such examples as: “HPV can cause cervical cancer and other cancers,” “HPV affects only women,” and “Children who receive HPV vaccine at a young age will have better immunity response compare to having it later.” Knowledge scores ranged from 0 to 7, computed by taking the total number of correct answers to the questions with a higher numeric value indicating better knowledge.

Decision-making factors.

Decision-making involving their spouse was measured with the item: “My spouse/partner will make the decision about children’s health issue, not me,” with response options of “yes” or “no.” Decision-making involving children was considered “yes” if participants answered either they “will talk with children about the HPV vaccine” or “want to wait until children can make their own decision about the vaccine.” Influence from peers was measured with the question whether or not they “will get their children vaccinated if their friends did the same to their children.” Participants were considered being influenced from doctors if they either “will bring children to get HPV vaccine because [they] trust [their] doctor” or “will get their children vaccinated if their family doctor recommended it.” We also asked whether the “pediatrician recommended [the] HPV vaccine.”

Beliefs regarding the HPV vaccine.

We examined beliefs by asking participants if they: (1) believed that the vaccine is pushed to make money for drug companies, (2) believed that HPV vaccination promotes early sex, and (3) if they have any safety concerns. More specifically participants’ safety concerns for the HPV vaccine were measured with 3 items, asking whether they “are afraid of the side effect of the HPV vaccine,” “think the vaccine was well tested before being made available to the public,” and “believe that HPV vaccine is safe and effective.” Participants who answered “yes” to the first question, or “no” to either one of the last 2 questions were coded as “having safety concerns.”

Data Analysis

To examine the association between each one of the predictors and the intention for children receiving the HPV vaccination, we conducted a bivariate analysis using a chi-square test for categorical predictors, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous predictors. For multivariable analysis, we used ordinal logistic regression to examine the association between intention of HPV vaccination for children, and knowledge of HPV and HPV vaccine, decision-making factors, and beliefs regarding HPV vaccine, while controlling for socio-demographic factors. Predicted probabilities were computed with other variables in the model held at their observed values.26 We conducted all analyses using Stata 14.27

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

The sample of this study consisted of 110 participants, specifically self-identified Chinese-American parents or legal guardians with at least one child aged 11 to 18 who had not been vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. As Table 1 shows, the sample consisted of 35 women (31.8%) and 75 men (68.2%), with an average age of 42.09. Only one of the participants was born in the US. On average, the participants had lived in the US. for 2.45 years, with a range between 3 months to 38 years. Half of the respondents had lived in the US for 15 or fewer years. The majority of the sample (55.45%) did not have a high school degree, and the rest (44.55%) had a high school or higher degree. Most (59.1%) had a household income between $10,000 and $30,000, and about one-fourth (24.5%) had a household income of more than $30,000.

Table 1.

Univariate and Bivariate Statistics (N = 110)

| N (%) or Mean (SD) | Range | p-value of association with parental intention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variable | |||

| Intention score | 2.16 (.78) | 0–3 | - |

| Sociodemoeravhic characteristics | |||

| Age | 42.09 (7.60) | 27–66 | ns |

| Sex | .012 | ||

| Female | 35 (31.8%) | ||

| Male | 75 (68.2%) | ||

| Years in the US | |||

| ≤ 15 years | 55 (50.0%) | ns | |

| > 15 years | 55 (50.0%) | ||

| Education | ns | ||

| Below high school | 61 (55.45%) | ||

| High school | 49 (44.55%) | ||

| Household income | ns | ||

| < $10,000 | 18 (16.3%) | ||

| $10,000 - $19,999 | 38 (34.6%) | ||

| $20,000 - $29,999 | 27 (24.6%) | ||

| ≥ $30,000 | 27 (24.5%) | ||

| Children-related factors | |||

| Sex of children | ns | ||

| All girls | 18 (16.4%) | ||

| All boys | 26 (23.6%) | ||

| Both girls and boys | 66 (60.0%) | ||

| Children insured | ns | ||

| Yes | 101 (91.8%) | ||

| No | 9 (8.2%) | ||

| Have regular pediatrician | ns | ||

| Yes | 104 (94.55%) | ||

| No | 6 (5.45%) | ||

| Children received HBV vaccination | ns | ||

| Yes | 91 (85.85%) | ||

| No | 15 (14.15%) | ||

| Missing | 4 | ||

| Pediatrician recommended HPV vaccine | .035 | ||

| Yes | 36 (32.7%) | ||

| No | 74 (67.3%) | ||

| Predictors | |||

| HPV knowledge score | 1.35 (1.98) | 0–7 | < .001 |

| Decision making will involve spouse | ns | ||

| Yes | 101 (91.8%) | ||

| No | 9 (8.2%) | ||

| Decision making will involve children | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 67 (60.9%) | ||

| No | 43 (39.1%) | ||

| Influenced by peers | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 44 (40.0%) | ||

| No | 66 (60.0%) | ||

| Influenced by doctors | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 93 (84.55%) | ||

| No | 17 (15.45%) | ||

| Believed vaccine is pushed to make money for drug companies | < .001 | ||

| Yes | 34 (30.9%) | ||

| No | 76 (69.1%) | ||

| Believed HPV vaccination promotes early sex act | < .006 | ||

| Yes | 76 (69.1%) | ||

| No | 34 (30.9%) | ||

| Have safety concerns | < .009 | ||

| Yes | 89 (80.9%) | ||

| No | 21 (19.1%) | ||

In total, the 110 participants had 170 children between the ages of 11 to 18, including 81 girls (47.65%), and 89 boys (52.35%). Sixty percent (60.0%) of the participants had both boys and girls, 23.6% had only boys, and 16.4% only had girls. Most reported that their children had insurance (91.9%), a regular pediatrician (94.6%), and received vaccination against hepatitis B virus (HBV) (85.9%). Yet, only one-third (32.7%) of the participants reported that their children’s pediatricians had recommended the HPV vaccination.

On a range from 0 to 3, the participants had an average intention level of 2.16. On a range from 0 to 7, the participants had an average HPV knowledge score of 1.35. Almost 92.0% of the participants would involve their spouse and 60.9% of them would involve their children in the decision-making process. Most participants reported that they were influenced by doctors (84.6%), and only 40.0% were influenced by their peers. Most participants believed that advocacy for the HPV vaccination was not motivated by an attempt to make money for drug companies (69.1%), but that the vaccination would promote early involvement in sexual activity (69.1%); in addition, 80.9% had concerns about the safety of the vaccine itself.

Prediction of Parental Intention of Vaccination for Children

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, children-related factors, and HPV-related predictors were tested for in their association with the outcome measure, parents’ intention to vaccinate their children against HPV. Table 1 presents these results. In the individual analyses, the following were statistically significant predictors: sex of the participants (p < .05), a prior recommendation of the HPV vaccine by a pediatrician (p < .05), HPV knowledge score (p < .001), involvement of children in the decision-making process (p < .001), the influence of peers (p < .001), influence of doctors (p < .001), and all 3 belief variables. These variables were all entered into the multivariate ordinal regression model. Although age, education, and time lived in the US were not statistically significant in bivariate analyses, they were statistically significant predictors in previous studies, and, therefore, were included as control variables in the multivariate analysis. Additionally, we also included spouse involvement in decision-making as a predictor of interest in the final model.

Table 2 presents the results of the ordinal regression. Four predictors were statistically significant. Greater parental intention was associated with a higher level of knowledge on HPV and the vaccine (OR = 1.32, p < .001), being influenced by doctors (OR = 8.80, p < .001), and having lived in the US for over 15 years (OR = 2.44, p < .05). In addition, those parents who said they would involve their children in making the decision were less likely to indicate intention to vaccinate their children. The following variables were not significantly related to parental intention of HPV vaccination for their children: whether the spouse would be involved in decision-making, peer influence, believing HPV vaccination promotes early sexual activity, and having safety concerns about the HPV vaccine, age, sex, and education level. Although previous pediatrician recommendation for the HPV vaccine was not statistically significant in the ordinal regression model, the odds ratio (1.39) indicates a positive association between pediatrician recommendation and parental intention. Whether participants believed that advocacy for the vaccine was related to making money for drug companies was marginally significant (OR = 2.92, p < .10). The odds ratio suggested a large effect of belief on intention, even though the p-value is above the .05 threshold. Contrary to the common interpretation of p-values in health literature,28 this finding does not indicate the lack of association between belief and intention regarding HPV vaccination among parents; rather, it suggests the need to examine this association further.

Table 2.

Ordinal Regression Results on Parental Intention of HPV Vaccination for Children (N = 110)

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of HPV & HPV vaccine | ||

| HPV knowledge score | 1.32* | (1.00, 1.75) |

| Decision-making | ||

| Will involve spouse (vs no) | .57 | (.10, 3.21) |

| Will involve children (vs no) | .30* | (.10, .92) |

| Influenced by peers (vs no) | 2.40 | (.81, 7.09) |

| Influenced by doctors (vs no) | 8.80*** | (2.62, 29.53) |

| Pediatrician recommended HPV vaccine (vs no) | 1.39 | (.51, 3.79) |

| Belief regarding HPV vaccine | ||

| Vaccine is pushed to make money for drug companies (vs no) | 2.92† | (.85, 10.04) |

| Believed HPV vaccination promotes early sex act (vs no) | 1.14 | (.29, 4.48) |

| Have safety concerns (vs no) | .94 | (.23, 3.82) |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Age | 1.00 | (.94, 1.06) |

| Female (vs male) | .88 | (.35, 2.18) |

| Having high school degree (vs not) | .52 | (.22, 1.27) |

| Lived in the US > 15 years (vs ≤ 15 years) | 2.44* | (1.01, 5.88) |

| Cut-point 1: −1.45 | ||

| Cut-point 2: −.33 | ||

| Cut-point 3: 3.58 | ||

| Likelihood Ratio Statistics = 56.93,*** df = 13 | ||

| McFadden’s | ||

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001, 2-tailed

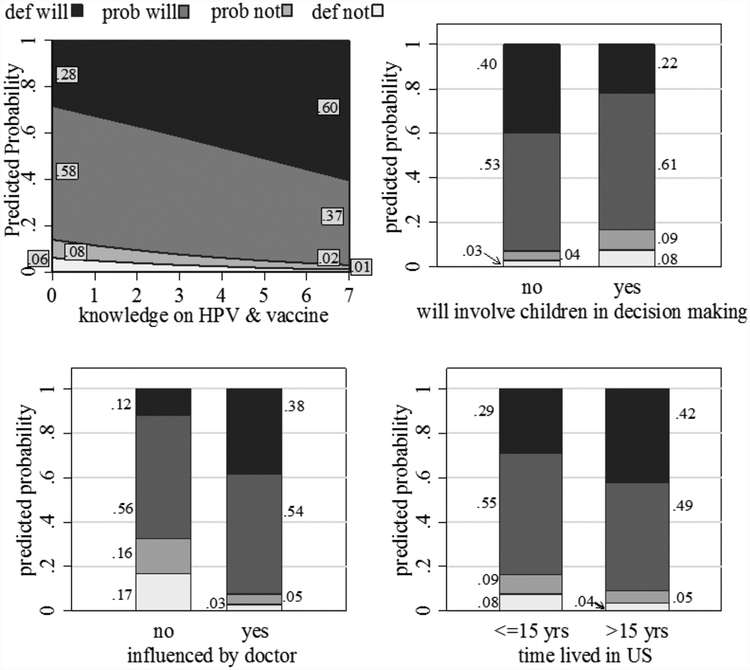

Because the predicted probability is a more direct and clear measure that makes more intuitive sense, the predicted probability of each level of intention was computed by the 4 statistically significant predictors (Figure 1). The upper left corner of Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of each intention level by knowledge scores. As the knowledge score increases from 0 to 7, the predicted probability of a parent saying they “definitely will” vaccinate their children increased from .28 to .60, a 114% increase. The probabilities of “probably will not” or “definitely will not” also decreased, from .08 to .02, and .06 to .01, respectively.

Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities of Parental Intention of HPV Vaccination for Children.

Note.

The predicted probabilities are calculated with other variables held at observed values.

The bar graph in the upper right corner of Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of intention level by whether parents will involve children in the decision-making process. The probability of “definitely will” was lower for those who would involve their children in decision-making (.22 vs .40). This finding is interesting because on the one hand, those parents who would involve their children were slightly more likely to say “probably will not” (.09 vs .04), or “definitely will not” (.08 vs .03), and less likely to say “definitely will” (.22 vs .40). This results suggests that parents anticipated reluctance or even refusal from their children on the matter, and such reluctance or refusal might change parental intention. On the other hand, parents who would involve their children in the decision-making process were also more likely than those who would not involve their children to say “probably will” (.61 vs .53). This would suggest that some parents are in favor of the vaccination; involving children in the decision-making is anticipated to be a delay rather than refusal of vaccination. In other words, they want to involve the children in decision-making, but they are still leaning strongly towards vaccination.

In the lower left corner of Figure 1, the bar graph shows the presented probability of intention level by doctor’s influence. Those parents who reported being influenced by doctors were much more likely to say that they “definitely will” (.38 vs .12), and the 2 groups were almost equal in the predicted probability of saying “probability will” (.54 vs .56). The large magnitude of the difference between the 2 groups indicates that doctors’ influence is a strong predictor of parental intention.

Lastly, the graph on the lower right corner of Figure 1 shows the effects of time lived in the US on intention. Parents who had lived in the US for over 15 years were more likely than those who lived in the US for ≤15 years to say they “definitely will” vaccinate their children (.42 vs .29), and much less likely to say that they “probably will not” (.05 vs .09) or “definitely will not” (.04 vs .08).

DISCUSSION

We examined knowledge, attitudes, and decision-making factors as correlates of parental intention to vaccinate their children against HPV in a community sample of Chinese-American parents and caregivers. First, parents’ knowledge about the virus and the vaccine was suboptimal. Moreover, knowledge about HPV and the vaccine was a statistically significant and independent correlate of parental intention to vaccinate children against HPV. Previous studies examining the role of knowledge in parental decision-making have yielded inconsistent results. Whereas a systematic review of the literature found greater knowledge to be related to greater intention or acceptability among US adolescents,29 some studies reported no relationship.30,31 However, these studies were all conducted on either ethnically diverse or non-Asian parents. Our findings indicate the need to increase HPV awareness and knowledge among Chinese-American parents to facilitate an informed decision regarding the HPV vaccine.

In addition, 2 decision-making factors were significantly associated with parental intention to vaccinate their children against HPV. First, parents who said they would involve children in decision-making had a lower intention to vaccinate their children than those who would not involve children. This finding highlights the importance of children’s intention in the decision-making process. It does not necessarily contradict the study finding that parents who would involve their children in decision-making reported a lower level of intention; rather, it suggests some uncertainty that was likely to be temporary (ie, a delayed decision rather than rejection of vaccination). This delayed decision or uncertainly could be due to parents’ lack of knowledge about their children’s opinion or intention or their knowledge or speculation of children’s reluctance towards vaccination. Either way, our findings demonstrate the necessity of open discussion between parents and children, as well as the necessity of increasing the knowledge of both parents and children. In addition, future intervention efforts should focus on facilitating open discussions between them.

Our findings also confirmed the strong influence of doctors in parental decision-making regarding HPV vaccination.32–34 More than three-fourths of parents reported being influenced by doctors. Previous research has found that people from collectivist cultures, Chinese included, see physicians as “a wise and benevolent authority figure.”35(p 117) Therefore, they tend to be heavily influenced by, or even defer decision-making to physicians. This highlights the necessity for greater campaign efforts to raise awareness of HPV and the HPV vaccine in doctors’ offices.

In addition, a study of a national sample of physicians found that many physicians recommended the HPV vaccine inconsistently, and without urgency.36 These practices may convey ambivalence to parents. A study of physician recommendations showed that compared to obstetricians/gynecologists, other doctors were significantly less likely to recommend the HPV vaccine, because the latter group considered such a recommendation the responsibility of the former group.37 Provider-oriented public health interventions are needed to foster consistent and urgent recommendation from physicians and other healthcare providers, including family doctors, pediatricians, and community health professionals. Such recommendations, paired with Chinese-American parents’ strong trust in physicians, would foster greater intention towards vaccination.

Finally, our findings show that parents who had lived in the US for ≤15 years lagged behind those who had lived in the US for over 15 years on the intention to vaccinate their children against HPV. This is consistent with the broader literature on vaccination among Asian immigrants, including influenza38 and hepatitis B vaccinations.39 One mechanism through which length of stay in the US was associated with vaccination intention is cultural norms. In contemporary Chinese culture, sexuality or sexual behavior is a taboo, an inappropriate or even offensive topic between parents and children.40,41 Parents might try to avoid any discussion on sexual activities with their children, hence the lack of vaccination intention. Still, under the heavy influence of the traditional philosophy of Confucianism, Chinese society considers sexual innocence until marriage a personal virtue that, if violated, brings shame to the family.42 This links to a fundamental problem with HPV, particularly in conservative Chinese society, which is that it is “perceived to be linked to culpable behavior, leaving room for responsibility attribution and moral stigmatization.”43(p 508) It is possible that the HPV vaccine is considered unnecessary if one is “sexually proper.” These cultural norms lead to a lack of communication between parents and adolescents on sex-related issues, which could then lead to parents’ lack of accurate information on their children’s sexual maturity (sexual debut, frequency of sexual activity, etc.) and specific behaviors (condom use, measures taken to prevent sexually-transmitted infections, etc). As a result, parents may convince themselves that there is (not yet) any need for their children to receive the vaccine, which is, in some way, avoidance of the awkward and uncomfortable conversation about sex. Alternatively, some parents (a striking 69.1% of the study sample) may inaccurately believe that HPV vaccination promotes early sexual activity, and therefore, choose to delay it44 or leave the decision to their children.45

Therefore, HPV vaccination campaigns need to disseminate adequate and accurate clinical information as well as take into account the cultural beliefs on sexual behaviors to foster preventive behavior without stigmatization. Culturally appropriate intervention efforts must include community-level interventions to address the cultural norms and barriers that affect parent-adolescent communication, joint decision-making, and the de-stigmatization of sex and sexual behaviors.

These results provide empirical support for the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which has been applied to the study of a wide range of health behaviors.46 Research shows that TPB provides a strong theoretical framework for preventive health behaviors, and more specifically, a powerful model to predict HPV vaccination intentions and behaviors.47,48 TBP posits that attitudes and subjective norms directly influence people’s intention, which in turn, influence the engagement in a behavior.49 Our findings further confirm the roles of knowledge, attitudes, and perceived norms, all of which are TBP constructs, in driving people’s intention.

This study is not without limitations. First, the analyses relied on self-reported data. Parents’ answers might have been affected by social desirability, which future research needs to consider. Second, the study sample was a non-random, regional community sample, which limited the generalizability of our findings. In addition, study participants were recruited from the local community health center. It is possible that they had greater health awareness and general knowledge and might have different perceptions about the HPV vaccine. Also, the race/ethnicity of the physicians was not obtained through the pre-test. It is possible that physician influence on the participants varied based on the race/ethnicity of the physician, and subsequently, the level of trust perceived by the participant. Nonetheless, our findings enrich the understanding of parental intentions regarding HPV vaccination among Chinese Americans, and identify areas of need in further facilitating HPV vaccination in this community.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the National Outreach Network (NON) - Community Health Educator (CHE) supplement grant that was funded by Center for Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (CRCHD), National Cancer Institute (NCI) (Grant Number: U54 CA153513; PI: Grace X. Ma, PhD). The authors thank clinical collaborator—Chinatown Medical Services (CMS) and their staff for their support and collaboration. The project was also partially supported by TUFCCC/HC Regional Comprehensive Cancer Health Disparity Partnership, Award Number U54 CA221704(5) (Contact PIs: Grace X. Ma, PhD and Olorunseun O. Ogunwobi, MD, PhD) from the National Cancer Institute of National Institutes of Health (NCI/NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI/NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure Statement

All authors of this article declare they have no financial or non-financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD facts – human papillomavirus (HPV). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- 2.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2012. STD surveillance other STDs. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats12/other.htm#hpv. Accessed February 15, 2017.

- 3.McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, et al. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(280):1–8. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db280.htm. Accessed June 21, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesson HW, Ekwueme DU, Saraiya M, et al. Estimates of the annual direct medical costs of the prevention and treatment of disease associated with human papillomavirus in the United States. Vaccine. 2012;30(42):6016–6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Villiers EM. Cross-roads in the classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2013;445(1):2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doorbar J, Quint W, Banks L, et al. The biology and life-cycle of human papillomaviruses. Vaccine. 2012;30:F55–F70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2008. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/index.html. Accessed July 10, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkin DM. The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006;118(12):3030–3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 10.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccine information for young women. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv-vaccine-young-women.htm. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 11.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). FDA licensure of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for use in males and guidance from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(20):630–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koutsky LA, Ault KA, Wheeler CM, et al. A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1645–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV vaccine recommendations | human papillomavirus. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/hpv/hcp/recommendations.html. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 15.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV | who should get vaccine | human papillomavirus. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine.html. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- 16.Allen JD, de Jesus M, Mars D, et al. Decision-making about the HPV vaccine among ethnically diverse parents: implications for health communications. J Oncol. 2011;2012:e401979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong MCS, Lee A, Ngai KLK, et al. Knowledge, attitude, practice and barriers on vaccination against human papillomavirus infection: a cross-sectional study among primary care physicians in Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marlow LAV, Waller J, Wardle J. Public awareness that HPV is a risk factor for cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(5):691–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trim K, Nagji N, Elit L, Roy K. Parental knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours towards human papillomavirus vaccination for their children: a systematic review from 2001 to 2011. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2011;2012:e921236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daley MF, Liddon N, Crane LA, et al. A national survey of pediatrician knowledge and attitudes regarding human papillomavirus vaccination. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2280–2289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waller J, Marlow LAV, Wardle J. Mothers’ attitudes towards preventing cervical cancer through human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006; 15(7): 1257–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisk LE, Allchin A, Witt WP. Disparities in human papillomavirus vaccine awareness among US parents of preadolescents and adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(2):117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population: 2010. 2010. Census briefs. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-11.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2014.

- 24.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV-associated cervical cancer rates by race and ethnicity. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/cervical.htm. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- 25.Gravitt PE, Nguyen RHN, Ma GX. Cervical cancer among Asian Americans In Wu AH, Stram DO, eds. Cancer Epidemiology among Asian Americans. New York, NY: Springer; 2016:271–285. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long JS, Freese J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. 3rd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodman S A dirty dozen: twelve p-value misconceptions. Semin Hematol. 2008;45(3):135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, et al. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dempsey AF, Zimet GD, Davis RL, Koutsky L. Factors that are associated with parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines: a randomized intervention study of written information about HPV. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1486–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenselink CH, Gerrits MMJG, Melchers WJG, et al. Parental acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;137(1):103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007;45(2–3):107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gonik B Strategies for fostering HPV vaccine acceptance. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2006;2006:e36797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zimet GD, Mays RM, Winston Y, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus immunization. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(1):47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific Islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23(2):116–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, et al. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnack JL, Reddy DM, Swain C. Predictors of parents’ willingness to vaccinate for human papillomavirus and physicians’ intentions to recommend the vaccine. Womens Health Issues. 2010;20(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quach S, Hamid JS, Pereira JA, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage across ethnic groups in Canada. CMAJ. 2012;184(15):1673–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma GX, Shive SE, Toubbeh JI, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of Chinese hepatitis B screening and vaccination. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(2):178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao E, Zuo X, Wang L, et al. How does traditional Confucian culture influence adolescents’ sexual behavior in three Asian cities? J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(3, Suppl):S12–S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Li X, Shah IH, et al. Parent–adolescent sex communication in China. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2007;12(2):138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillan J, Sex, Science and Morality in China. London, UK: Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwan T, Chan K, Yip A, et al. Acceptability of human papillomavirus vaccination among Chinese women: concerns and implications. BJOG. 2009;116(4):501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang HS, Moneyham L. Attitudes toward and intention to receive the human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination and intention to use condoms among female Korean college students. Vaccine. 2010;28(3):811–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanderpool RC, Cohen E, Crosby RA, et al. “1–2–3 Pap” intervention improves HPV vaccine series completion among Appalachian women. J Commun. 2013;63(1):95–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11(2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerend MA, Shepherd JE. Predicting human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young adult women: comparing the health belief model and theory of planned behavior. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44(2):171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Askelson NM, Campo S, Lowe JB, et al. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict mothers’ intentions to vaccinate their daughters against HPV. J Sch Nurs. 2010;26(3):194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ajzen I The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211. [Google Scholar]