Abstract

Background:

Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is a global health problem. Since Saudi Arabia is becoming more open to the world, it is important to assess future doctors’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAPs) regarding HIV/AIDS and people living with HIV (PLHIV).

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study included 204 male medical students of Qassim University who answered a self-administered questionnaire about HIV KAPs.

Results:

The mean HIV knowledge (HK) and attitude scores were 11.62 (64.5%) and 37.82 (67.5%), respectively. Positive correlations were observed between HK and attitude (r = 0.266) and HK and academic year (r = 0.277). No significant correlation was found between attitude and academic year (r = 0.097). More than half of the students exhibited ignorance about some modes of transmission such as deep kissing and vertical transmission. Around 81% of the students stated that they would not visit the homes of friends with HIV-infected members. Furthermore, 73.1% of the participants indicated that they would not provide care to HIV-positive relatives in their own homes.

Conclusions:

The findings show a modest level of HK and negative attitudes toward PLHIV. The study identified the main knowledge gaps in the transmission and prevention of HIV. Educational institutions should tailor their educational approach based on the identified gaps, which might help to ease the stigma and negative attitudes.

Keywords: Attitude, Human immunodeficiency virus, Knowledge, Medical student, Saudi Arabia, Stigma

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a major public health issue worldwide, which resulted in more than 35 million deaths until 2017. About 36.9 million people were living with HIV (PLHIV) at the end of 2017.[1] In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), at the end of 2015, there were 22,952 cases of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): Two-thirds of these cases were observed in non-Saudi populations and 1191 were newly detected cases.[2] Furthermore, in 2016, approximately 8000 people aged 15 years and older were living with HIV; 72.5% of these people were male and 27.5% were female.[3]

Medical students are future health-care providers. The attitude of a health-care provider toward a patient plays an important role in the determination of the patient’s medical outcomes and health-related behavior.[4,5] Negative attitudes or prejudice, as perceived by patients, are associated with a lower quality of care,[5,6] decreased care-seeking by patients,[7,8] reduced treatment adherence,[9,10] and poor medical outcomes.[11,12] The higher the level of HIV knowledge (HK), the lower the level of intolerance and anxiety among medical personnel.[13-17] Knowledge on HIV stigma and discrimination is a prognosticator of less discriminatory attitudes toward HIV/AIDS patients at work.[18] Studies in Poland and the United Kingdom indicated that positive attitudes and reductions in the level of fear were inculcated through medical school attendance and clinical training.[19,20]

Globally, many studies have measured the level of knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/PLHIV among medical students. In Fiji, medical students showed a high level of HK and positive attitude. Nevertheless, a large proportion of participants admitted to having a fear of dealing with HIV patients through clinical practice.[21] A study in Russia reported that a majority of medical students have negative attitudes toward PLHIV. The reluctance to treat was more apparent among clinical years’ students.[22] In an Islamic country like Pakistan, a study showed strong negative attitudes regarding HIV/AIDS and PLHIV. Around 64% of the participants said that children with HIV infection should be forbidden from attending public schools.[23] Moreover, Malaysian study reported negative beliefs regarding disclosure, confidentiality, and environment of care toward PLHIV. However, the attitudes toward giving care to PLHIV were positive.[24]

Few studies have covered specific populations in KSA in this context. For example, a study of the general population in Jeddah reported a modest mean knowledge level with 5.2 out of 9 points. However, the attitude was negative, with more than 40% of people agreeing that PLHIV should be isolated.[25] Furthermore, a study on 1483 doctors showed poor levels of HIV-related knowledge, with those pertaining to the modes of transmission being the lowest.[26] Another study on male applied medical science students found negative attitudes and a low level of awareness in terms of the modes of HIV transmission; for example, 54% of them were unaware that the act of spitting or coughing cannot lead to HIV transmission.[27] In addition, paramedical students showed a lack of knowledge regarding HIV transmission and the means for prevention, with unfavorable attitudes toward PLHIV.[28]

Holding discussions on sexuality are a challenge in a conservative country such as KSA. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of future doctors, as they are likely to be in direct contact with PLHIV and be a source of correct medical information. Hence, the aim of this study was to measure medical students’ knowledge, attitude, and beliefs regarding HIV/AIDS and PLHIV. We believe our findings will aid in the establishment of a basis for further research in this field and help other colleges to modify their approach toward HIV/AIDS accordingly.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted among medical students of Qassim University in Saudi Arabia between February and March 2017. Because of the separation between male and female students and certain cultural issues, as well as the sensitivity associated with the topic, we included male students only. A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit participants; all students who were present in the classes received the survey, and the absent students were followed twice. The questionnaires were distributed by members of the research team (University Faculty was not involved) and the participation was voluntary.

The questionnaire comprised three parts: Sociodemographic (age and academic year), HK, and attitudes toward HIV/PLHIV. The second part measured the level of HIV-related knowledge using a validated reliable 18-item HK questionnaire that assesses participants’ knowledge of disease prevention and sexual transmission.[29] Items adopted a “true,” “false,” or “do not know” scale, and were marked as correct or incorrect. “Do not know” responses or not responding to an item were marked as “incorrect.” The attitude part was based on previous literature and consultation with the microbiology department. It consisted of 14 questions that measure the attitudes toward and beliefs about HIV infection and PLHIV using a 4-point Likert scale of “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “agree,” or “strongly agree”.[21] Positive attitude statements were coded in the following manner “strongly agree = 4” to “strongly disagree = 1” while negative attitude statements were coded in the opposite manner. The total attitude section score ranged from 14 to 56.

Before the official survey, the questionnaire was randomly piloted on ten medical students to ensure clarity and confirm that all the respondents understood the content. However, the participants of the pilot study were not involved in the final study. The questionnaire was clear to them and no changes have been made.

All data were entered using Microsoft Excel (2010) and analyzed using SAS software, Version 9.4 of SAS system for Windows. The population was described using descriptive analysis. The percentages expressed after mean scores are calculated as the mean score of students divided by total scale score multiplied by 100. One-way analysis of variance and F-test was used to compare the mean HIV-related knowledge and attitude scores between academic year groups, while an independent sample t-test was used to compare the mean HIV-related knowledge and attitude scores between age groups. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact were used to compare the attitude and practice responses between the groups. Spearman’s correlation was used to investigate the relationship of HK score and attitude score with the academic year, as well as to examine the relationship between the HK and attitude scores. Statistical significance was set at a value of 0.05 or lower.

The study was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee of Qassim province and registered at the National Committee of BioEthics. All participants provided informed consent before participation.

Results

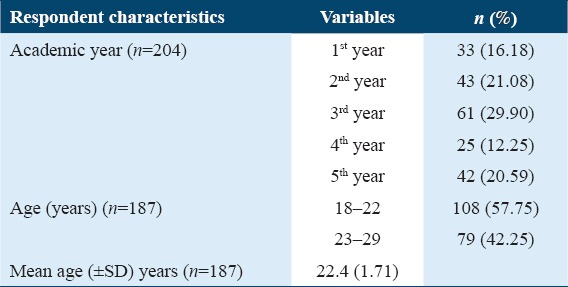

Table 1 showcases the demographic characteristics of the participating students.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

The total questionnaires distributed were 437, and 204 were filled out by the students giving a response rate of 46.68%. A majority of the medical students 137 (67.1%) were from the basic year classes (years 1–3), while 67 (32.9%) were from the clinical year classes (years 4–5). The mean age (±standard deviation [SD]) of the 204 participants was 22.37 (± 1.71) across both the basic and clinical medical years. Most of the participants (57.75%) were aged 18–22 years, and the remaining (42.25%) were aged 22–29 years. A majority of the participants 61 (29.90%) were from the third academic year, while the lowest number of respondents 25 (12.25%) was from the fourth academic year [Table 1].

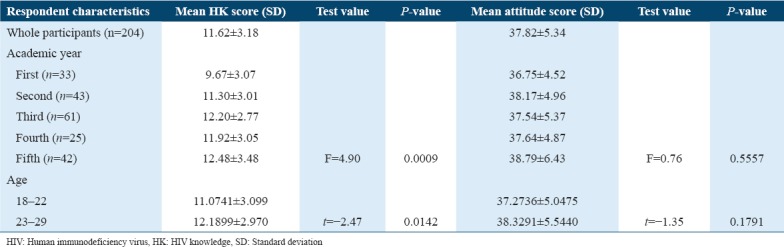

The mean HK score (SD) was 11.62 ± 3.18 (64.5%). The knowledge scores varied from 1 to 18. Only two students (0.9%) scored 18 out of 18, and the percentage of students who scored 16 or above was 6.3%. A difference in the mean HK score was observed between students in the different academic years (F [n = 204] = 4.90, P = 0.0009) [Table 2]. Those in their first academic year showed the lowest mean knowledge score (SD) (9.67 [± 3.07]), while those in the 5th year had the highest mean knowledge score (SD) (12.48 [± 3.48]), as shown in Table 2. We found positive correlations between the HK score and academic year (r = 0.27684, P ≤ 0.0001). In addition, a positive correlation was observed between HK and the students’ age (r = 0.26748, P = 0.0002).

Table 2.

Summary of HIV knowledge (HK) and attitude scores

The mean attitude score was 37.82 ± 5.34 (67.54%). No variations were found between the attitude score and the academic year of the students or their age [Table 2]. No significant correlation (r = 0.09734, P = 0.1682) was observed between students’ attitudes and their academic year. A positive correlation was found between students’ attitude scores and HK scores (r = 0.26595, P ≤ 0.0001).

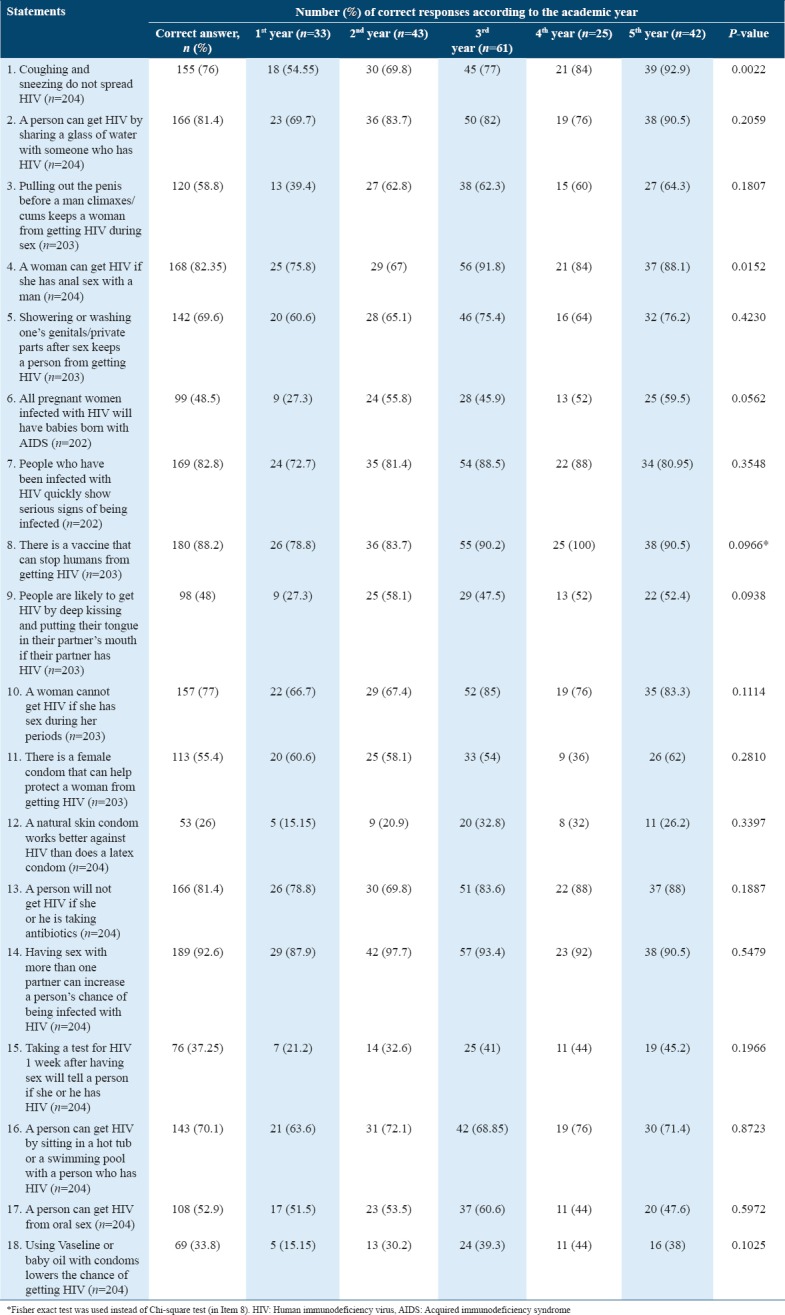

Table 3 shows the analysis of each question related to HK by academic year (including basic and clinical years). Question No. 14 (14. Having sex with more than one sexual partner can increase a person’s chance of contracting HIV infection) had the highest number of correct answers (189 correct answers), while question No. 12 (12.A natural skin condom works better against HIV transmission than a latex condom) was the question with the lowest number of correct answers. Overall, for 11 of the 18 questions at least 120 correct answers were observed. Of these, for six questions, more than 160 correct answers were observed.

Table 3.

Level of knowledge about human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS

Comparison by students’ academic year showed remarkable differences in two of the 18 (11.1%) questions. Only 54.55% of the 1st year students scored a correct answer in the first question (1. HIV is not transmitted through coughing and sneezing), while 92.9% of the 5th-year students correctly answered the same question. A significantly higher number of 5th-year students, compared to the other students, were aware that coughing and sneezing did not lead to HIV transmission (χ2=16.6914, P = 0.0022). The 4th-year students were significantly more aware that a woman can contract HIV if she has anal sex with a man than those in the other academic years (χ2=12.3146, P = 0.0152). The 1st year students had the lowest percentage of correct answers to most of the knowledge-based questions, especially the last few questions (using Vaseline or baby oil with condoms lowers the chance of contracting HIV) to which only 15.15% of them provided correct answers. A total of 61.6% of the 1st year students mistakenly thought that pulling out the penis before climaxing during sex can prevent the transmission of HIV to the woman [Table 3].

Comparisons between the age and knowledge scores found significant differences in the answers to three of the 18 questions. All three questions showed significantly higher scores in those aged 23 years or older. Older respondents (23 years or older), compared to their younger counterparts (22 years or younger), appeared to be significantly more knowledgeable on the following: HIV is not transmitted through coughing and sneezing (χ2 = 9.7384, P = 0.0018); there is a vaccine that can prevent a person from contracting HIV (χ2 = 5.2180, P = 0.0224); and getting tested for HIV 1 week after having sex will tell a person if she or he has HIV (χ2 = 5.0097, P = 0.0252). Otherwise, no noticeable difference was found in the remaining 15 questions [Table 3].

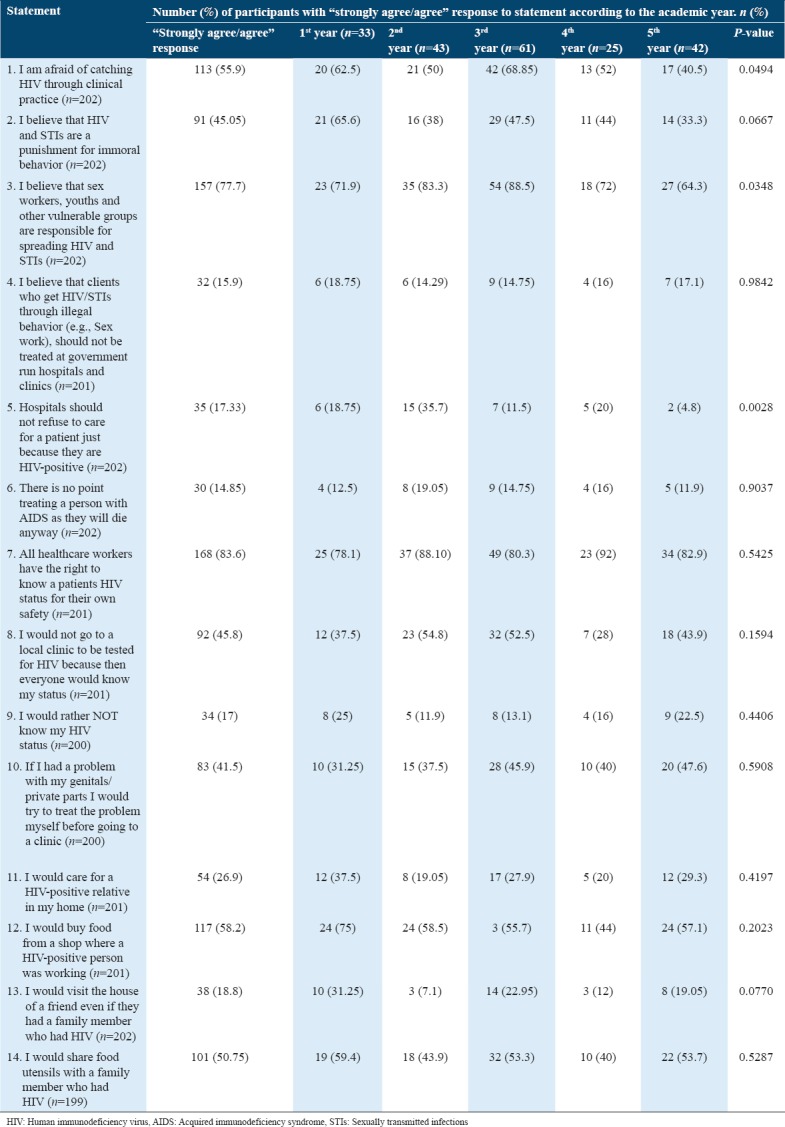

Table 4 showcases a summary of the responses pertaining to students’ attitudes and beliefs about HIV and AIDS. Approximately half of the students (55.9%) indicated that they were afraid of contracting HIV through clinical practice. In addition, almost half of the students (45.05%) believed that HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a punishment for immoral behavior, and 77.7% of them believed that sex workers, youths, and other vulnerable groups are responsible for the transmission of HIV and STIs. A total of 15.9% of the students believed that those who contracted HIV through illegal behavior should not be treated in government-run facilities and 14.85% of them believed that there is no point in treating a person with AIDS as they will die anyway. A large number of students (83%) agreed that they would like to know their HIV status. Only 18.8% of the participants responded that they would visit a friend’s house that has an HIV-infected member, while 26.9% would care for someone living with HIV at home. Furthermore, more than half of students would purchase food from a shop in which an HIV-positive person works and share food utensils with a family member who has HIV.

Table 4.

Students attitudes and beliefs about human immunodeficiency virus

Comparisons of the attitude scores by academic year found that the responses to three of the 14 questions were remarkably different. A total of 68.85% of the students in the 3rd year were afraid of contracting HIV through clinical practice, compared to the 62.5% students in the 1st year, 52% in the 4th year, 50% in the 2nd year, and 40.5% in the 5th year (χ2 = 9.5188, P = 0.0494). A larger number of second (83.3%) and third (88.5%) year students believed that sex workers, youths, and other vulnerable groups are responsible for the transmission of HIV and STIs compared to the first (71.9%), fourth (72%), and fifth (64.3%) year students (χ2 = 10.3589, P = 0.0348). In addition, a larger proportion of 2nd year students (35.7%) believe that hospitals should not refuse to care for a patient just because they are HIV-positive, compared to those in the first (18.75%), third (11.5%), fourth (20%), and fifth (4.8%) years (χ2 = 16.1701, P = 0.0028) [Table 4].

A comparison of the attitude scores by age showed significant differences in the responses to three of the 14 questions. A larger number of younger students (22 years or younger) than older respondents (23 years or older) (62.3% vs. 46.8%) were afraid of contracting HIV through clinical practice (χ2 = 4.3663, P = 0.0367). In addition, a higher proportion of students aged 22 years or younger than those aged 23 years or older (55.66% vs. 36.7%) believed that sex workers, youths, and other vulnerable groups are responsible for the transmission of HIV and STIs (χ2 = 6.5184, P = 0.0533). Similarly, a larger proportion of younger students (22 years or younger) (67%) responded that they would buy food from a shop in which an HIV-positive person works, compared to the older students (23 years or older) (46.8%) (χ2 = 7.5606, P = 0.0060) [Table 4].

Discussion

This present study explored medical students’ knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding HIV/AIDS and PLHIV at Qassim University in KSA and provided important insights into this field. Our findings revealed a modest level of HIV-related knowledge among the students, as well as negative attitudes toward PLHIV. The mean HK score of 11.62 (64.5%) indicated a low level of knowledge compared to that observed in studies conducted in Fiji and the United States.[21,30] Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between knowledge and attitude, consistent with previous studies.[31,32] We also observed a positive correlation between knowledge and academic year, which is similar to international studies in Fiji, Malaysia, and Turkey.[21,31,32] However, there was a huge difference between the 1st year and the other years that is probably because the college curriculum structure teaches HIV topic in the 2nd year and beyond. The study also found a poor level of knowledge regarding HIV transmission. For instance, 41.2% of the students believed that pulling out the penis before climaxing during sex can prevent the transmission of HIV to the woman. Moreover, around half of the students had misconceptions about vertical transmission, compared to <40% of applied medical science college students in the same country.[27] Similarly, almost half of the participants believed in transmission through deep kissing and oral sex. However, the majority of students knew that sharing a glass of water does not transmit the disease, while 74% of practicing doctors in KSA believe it does transmit the disease.[26] This is a sign that education has improved and can improve future doctors’ knowledge in the upcoming years.

As for prevention, only 26% of the participants knew that the use of latex condoms was better than natural skin condoms in the prevention of HIV transmission, while 33.8% responded that the use of Vaseline or baby oil with condoms lowered the chance of contracting HIV. Hence, these findings point to the students’ poor levels of awareness on HIV transmission as well as prevention, consistent with other studies performed in Saudi Arabia.[25-28] This may be due to low HIV prevalence,[2] inadequate education and being an Islamic conservative community that rarely talks about sex openly.

In terms of attitudes and beliefs pertaining to HIV, almost half of the respondents believed that HIV is a punishment for immoral behavior; which is close to another study in KSA, in which 38% agree on that,[26] but the percentage of this belief is high compared to only 23% in Fiji.[21] Such beliefs may stem from the stigma surrounding PLHIV due to cultural and religious reasons, and how the disease is incorrectly connected to groups of people who are looked down on.[33] The attitudes also revealed that more than three-fourths of the students believe that sex workers, youths, and key at-risk populations were responsible for HIV transmission. However, a low level of knowledge about other routes of transmission such as blood transfusion and vertical transmission may increase the level of stigma against PLHIV because these other routes are not related to immoral behavior. Furthermore, about half of the respondents were afraid of contracting HIV during clinical practice. While the first case of HIV transmission was recorded almost four decades ago, fear and prejudice surrounding the disease as well as PLHIV still prevail in Saudi Arabia. This prejudice and fear can be assuaged through the provision of education on the modes of HIV transmission. In our research, we did not observe any difference in the attitudes toward HIV on comparing the participants in the basic and advanced clinical years, inconsistent with the findings of Choy et al. who found better attitudes among participants in their clinical years.[24] Better attitudes among clinical-level participants were also observed by Bikmukhametov et al.[22] Notably, a majority of the participants in this study agreed that all healthcare workers should be made aware of patients’ HIV status. This is against a patient’s bill of rights in KSA, which states that only the medical team that is responsible for providing care to the patient should be aware of his/her HIV status.[34] Poor attitudes toward PLHIV may result in continued prejudice and stigma surrounding HIV, which may impede the provision of optimal health care for PLHIV and the prevention of new cases in KSA and the Middle East.

The students had an apparent fear of contact with PLHIV. For example, while more than half of the participants expressed their willingness to purchase food from a shop owned by an HIV-positive person, and share food utensils with a family member who has HIV, only a quarter of the participants indicated they would care for a close relative with the disease. This finding was distinguishably different from that reported by Zaini, who found that more than half of applied medical science students would care for an HIV-positive relative,[27] as well as that reported by Lui et al., who found that four-fifths of the participants would care for an HIV-positive relative.[21] In addition, only one-fifth of the participants in the current study said they would visit the house of a friend who has an HIV-positive family member. This is in contrast to the findings of Lui et al. who found that almost all the participants would visit the house of a friend who has an HIV-positive family member.[21] A Turkish study shared this common finding too.[32] This may be an indication that the stigmatization and prejudice toward PLHIV could surpass cultural and religious values regarding family and the duties one has toward it.

This study has some limitations. First, the generalizability of the findings to all medical students may be limited by some factors, such as volunteer bias and low representation of participants from some academic years. It is also possible that some of the statements or questions may have been misunderstood by the respondents despite the pilot study. Finally, the validated HIV KQ-18 is a shorter form of HIV KQ-45, which is more comprehensive.[29] However, it will take more time to be filled and may reduce the response rate, so we preferred the short one.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the enrolled population of Saudi medical students had major misconceptions regarding HIV/AIDS as well as negative attitudes toward PLHIV. As a result, they seemed reluctant and afraid to deal with PLHIV. This may, in the future, jeopardize patient-doctor relationships, leading to poor health care outcomes. Thus, there is an urgent need for universities to improve their curricula and fill the knowledge gaps that have been highlighted in this study. In addition, students should be equipped with humane attitudes throughout their curriculum and clinical practice. Finally, future studies on the topic should be conducted with a larger representative sample size on a national scale.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to all the participants for their time and effort. The authors also thank Dr. Raheel Shafi, head of Microbiology and Immunology Department, Qassim University, for his support and encouragement.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Fact Sheet HIV/AIDS. [[Last accessed on 2018 Oct 26]]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids .

- 2.MOH Saudi Arabia. MOH:1,191 New AIDS Cases in the Kingdom during. 2015. [[Last cited on 2018 May 26]]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2016-11-30-001.aspx .

- 3.UNAIDS. Saudi Arabia Country Factsheets. [[Last cited on 2018 May 26]]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/saudiarabia .

- 4.Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:553–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions:Do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:248–55. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding L, Landon BE, Wilson IB, Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Cleary PD, et al. Predictors and consequences of negative physician attitudes toward HIV-infected injection drug users. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:618–23. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malta M, Bastos FI, Strathdee SA, Cunnigham SD, Pilotto JH, Kerrigan D, et al. Knowledge, perceived stigma, and care-seeking experiences for sexually transmitted infections:A qualitative study from the perspective of public clinic attendees in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hausmann LR, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1679–84. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0730-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waite KR, Paasche-Orlow M, Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Literacy, social stigma, and HIV medication adherence. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1367–72. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0662-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Schulman KA, et al. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:473–82. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee C, Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. The association between perceived provider discrimination, healthcare utilization and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19:330–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royse D, Birge B. Homophobia and attitudes towards AIDS patients among medical, nursing, and paramedical students. Psychol Rep. 1987;61:867–70. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1987.61.3.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordin FM, Willoughby AD, Levine LA, Gurel L, Neill KM. Knowledge of AIDS among hospital workers:Behavioral correlates and consequences. AIDS. 1987;1:183–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ficarrotto TJ, Grade M, Bliwise N, Irish T. Predictors of medical and nursing students'levels of HIV-AIDS knowledge and their resistance to working with AIDS patients. Acad Med. 1990;65:470–1. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tesch BJ, Simpson DE, Kirby BD. Medical and nursing students'attitudes about AIDS issues. Acad Med. 1990;65:467–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199007000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bektaş HA, Kulakaç O. Knowledge and attitudes of nursing students toward patients living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV):A Turkish perspective. AIDS Care. 2007;19:888–94. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Platten M, Pham HN, Nguyen HV, Nguyen NT, Le GM. Knowledge of HIV and factors associated with attitudes towards HIV among final-year medical students at Hanoi medical university in Vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leszczyszyn-Pynka M, Hołowinski K. Attitudes among medical students regarding HIV/AIDS. Med Wieku Rozwoj. 2003;7:511–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivens D, Sabin C. Medical student attitudes towards HIV. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:513–6. doi: 10.1258/095646206778145631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lui PS, Sarangapany J, Begley K, Coote K, Kishore K. Medical and nursing students perceived knowledge, attitudes, and practices concerning human immunodeficiency virus. [[Last cited on 2018 Feb 11]];ISRN Public Health. 2014 2014:1–9. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/archive/2014/975875 . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bikmukhametov DA, Anokhin VA, Vinogradova AN, Triner WR, McNutt LA. Bias in medicine:A survey of medical student attitudes towards HIV-positive and marginalized patients in Russia, 2010. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17372. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.2.17372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaikh FD, Khan SA, Ross MW, Grimes RM. Knowledge and attitudes of Pakistani medical students towards HIV-positive and/or AIDS patients. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:7–17. doi: 10.1080/13548500500477667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choy KK, Rene TJ, Khan SA. Beliefs and attitudes of medical students from public and private universities in Malaysia towards individuals with HIV/AIDS. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:462826. doi: 10.1155/2013/462826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alwafi HA, Meer AMT, Shabkah A, Mehdawi FS, El-Haddad H, Bahabri N, et al. Knowledge and attitudes toward HIV/AIDS among the general population of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J Infect Public Health. 2018;11:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Memish ZA, Filemban SM, Bamgboyel A, Al Hakeem RF, Elrashied SM, Al-Tawfiq JA, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of doctors toward people living with HIV/AIDS in Saudi Arabia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:61–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaini RG. A study on knowledge and awareness of male students of the college of applied medical science at Taif university. [[Last cited on 2018 May 12]];J AIDS Clin Res. 2016 7:1–4. Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/a-study-on-knowledge-and-awareness-of-male-students-of-the-college-ofapplied-medical-science-at-taif-university-2155-6113-1000574.php?aid=72580 . [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Mazrou YY, Abouzeid MS, Al-Jeffri MH. Knowledge and attitudes of paramedical students in Saudi Arabia toward HIV/AIDS. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:1183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:172–82. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.2.172.23902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.James TG, Ryan SJ. HIV knowledge mediates the relationship between HIV testing history and stigma in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2018;66:561–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2018.1432623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chew BH, Cheong AT. Assessing HIV/AIDS knowledge and stigmatizing attitudes among medical students in Universiti Putra Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2013;68:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turhan O, Senol Y, Baykul T, Saba R, Yalçin AN. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of students from a medicine faculty, dentistry faculty, and medical technology vocational training school toward HIV/AIDS. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2010;23:153–60. doi: 10.2478/v10001-010-0008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCann TV. Willingness to provide care and treatment for patients with HIV/AIDS. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1033–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. Patient's Bill of Rights and Responsibilities. [[Last cited on 2018 Nov 07]]. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/HealthTips/Pages/Tips-2011-1-29-001.aspx .