Abstract

The blood brain barrier (BBB) segregates the central nervous system from the systemic circulation. As such, the BBB prevents toxins and pathogens from entering the brain, but also limits the brain uptake of therapeutic molecules. However, under certain pathological conditions, the BBB is disrupted, allowing direct interaction between blood components and the diseased site. Moreover, techniques like focused ultrasound can further disrupt the BBB in diseased regions. This review focuses on strategies that leverage such BBB disruption for delivering nanocarriers to the central nervous system (CNS). BBB disruption, as it relates to nanocarrier delivery, will be discussed in the context of acute pathologies such as stroke and traumatic brain injury, as well as chronic pathologies such as brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Key aspects of nanocarrier design as they relate to penetration and retention in the CNS are also highlighted.

Keywords: BBB disruption, nanocarrier, neuropathology, FUS

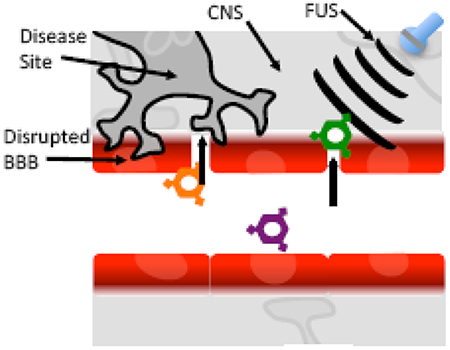

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is formed by brain endothelial cells and segregates blood components from the central nervous system (CNS) using specialized physical, transport and metabolic properties [1]. While a subset of small, lipophilic molecules can diffuse readily through the BBB, nucleic acid, peptide, protein and nanoparticulate therapeutics that could be highly desirable for treating CNS disorders cannot directly access the CNS. As such, several strategies to circumvent the BBB to deliver therapeutics are being investigated including utilizing receptor-mediated machinery to transcytose through brain endothelial cells[2], implanting therapeutic materials within the CNS[3], administering therapeutics by intranasal and intrathecal routes[4], among others[5]. These strategies have been reviewed elsewhere in the literature[2,4–7]. In this review, we will instead focus on emerging approaches to target therapeutics to the CNS that exploit pathologic or induced BBB disruption.

Additionally, this review selectively focuses on therapeutic applications that employ nanocarriers for cargo delivery. Nanocarriers are of particular interest as a drug delivery platform to treat CNS disease. This class of particles, including but not limited to nanoparticles and liposomes, have beneficial properties compared to unconjugated small molecules and therapeutic proteins. These include the ability to employ surface modifications that can drive desirable CNS penetration, enhance pharmacokinetic properties, and target specific cells or structures[8]. Additionally, nanocarriers carry concentrated small molecule and therapeutic protein payloads that result in increased accumulation of drug at the target site, as well as controlled release of therapeutic payload to reduce off target adverse events[9,10].

While nanocarrier delivery to the CNS using transcytosis, intranasal and intrathecal delivery has been discussed elsewhere, this review focuses on targeting nanocarriers to sites of BBB disruption resulting from neuropathology or medical intervention. We describe evidence that supports BBB disruption as a means to deliver therapeutic nanocarriers loaded with small molecules, nucleic acids or proteins to various CNS disease conditions. CNS pathology-induced BBB disruption can serve as a nanocarrier access point to diseased sites in certain conditions. In addition, transient BBB disruption by administration of chemical agents or focused ultrasound can also serve as an access point for nanocarriers to accumulate in diseased CNS tissue.

Pathologic BBB Disruption

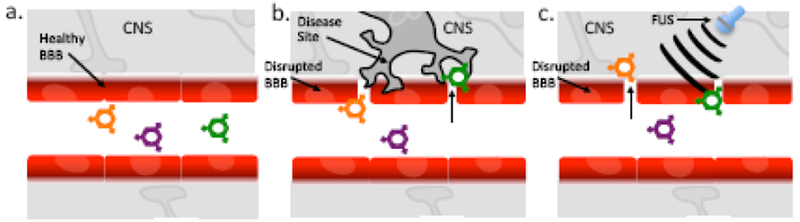

While one most often considers identifying drug delivery strategies that overcome an intact BBB to access disease tissue (Figure 1a), certain neuropathologies, including acute events such as stroke and traumatic brain injury as well as chronic events like brain tumors, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s disease, exhibit partial or complete BBB disruption as a pathological hallmark of the diseased site[11–15]. Thus, a therapeutic nanocarrier administered intravenously, could in theory, directly accumulate in diseased regions exhibiting pathologically disrupted BBB (Figure 1b). Furthermore, unaffected CNS regions remain behind an intact BBB limiting CNS contact with blood components, including therapeutic nanocarriers, and potentially minimizing adverse events related to the therapeutic cargo. However, pathologic BBB disruption is complex and unique to each disease. For example, ischemic stroke often exhibits multi-phasic BBB disruption[16]; while in brain tumors, the BBB tends to exhibit partial disruption that varies from tumor to tumor, even within a single patient in the case of metastatic tumors[17]. Nonetheless, as data continue to emerge, it appears that leveraging pathologic BBB disruption for therapeutic nanocarrier delivery may be an effective strategy in multiple neurological disease states.

Figure1. Impact of BBB disruption on Particle Access to CNS.

a) Under normal conditions healthy, intact BBB separates the CNS from blood components thereby preventing nanocarriers from accessing CNS. b) Under conditions in which a disease induces pathologic BBB disruption, therapeutic nanocarriers can directly Interact with disease site. c) Focus Ultrasound (FUS) can exert mechanical forces that temporarily disrupt the BBB allowing therapeutic nanocarriers to directly Interact with the CNS.

Induced BBB Disruption

Not all CNS diseases lead to complete, uniform BBB disruption across the pathologic site. Thus strategies can be employed to induce BBB permeability to facilitate nanoparticle delivery. Administration of chemical agents such as mannitol[18] and adenosine A2A agonist[19] transiently disrupt the BBB through hyperosmolarity and interaction with adenosine receptor, respectively but lack regiospecific targeting capability. In contrast, focused ultrasound (FUS) in conjunction with microbubbles also induces temporary BBB disruption, with sub millimeter precision in a defined region[20–22]. Thus, focused ultrasound could allow for intravenously administered therapeutic nanocarriers to access a diseased brain region without exposing substantial healthy CNS tissue to blood components or drug-loaded nanocarriers.

Considerations in Utilizing BBB Disruption for Nanocarrier Delivery

Conceptually, using pathologic BBB disruption as a mechanism for allowing nanocarrier access to sites of CNS disease is related to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect described as responsible for accumulating nanocarriers in solid peripheral tumors that have defective vascular architectures. However, while multiple neuropathologies exhibit some type of enhanced vascular permeability, there is little evidence of retention as a function of particle size[23,24]. This lack of an observable EPR effect in the CNS could be due to a variety of causes, some of which may reflect the anatomy of the CNS. For instance, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is completely replaced every 4–6 hours, potentially limiting nanocarrier retention[25]. Additionally, studies of brain interstitial space indicate that it is dense and highly charged, thereby limiting the movement of many classes of nanocarriers within the CNS[26]. Thus, while utilizing BBB disruption to deliver nanocarriers is similar to exploiting the EPR effect, the anatomical nature of the CNS limits the both the penetration and retention of nanocarriers throughout the diseased site. This issue can be circumvented in two major ways. First, deformable, small nanocarriers are formulated with surface modifications that mask the particle charge thus allowing more uniform brain penetration. One example of this approach is modifying >50nm liposomes with PEG chains[8]. Second, modifying a nanocarrier with targeting motif can enhance retention in a diseased site. Most commonly employed are nanocarriers modified with targeting motifs with affinity for disease cells or extracellular matrix (ECM) that facilitate accumulation and retention of a therapeutic within the pathologic site. Thus, disrupted BBB can be targeted with nanocarriers that are specially formulated for penetration and retention at the diseased site.

Below we describe several neurological diseases that have been examined in the context of leveraging BBB disruption for nanocarrier delivery. For each disease, we will summarize the evidence that the BBB is disrupted as well as describe the use of pathologically disrupted BBB or focus ultrasound (FUS) disrupted BBB to deliver nanocarriers to sites of CNS disease (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

| Studies Utilizing Pathologic BBB Disruption | Neuropathology | Particle Type | Therapeutic Payload |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madhankumar AB et al. [28] | U87 GBM | IL-13r targeting Liposomes | Doxorubicin |

| Sattiraju A et al. [29] | U87 GBM | αvβ3-targeting Liposomes | 225Ac |

| Sun Z et al. [26] | C6 Glioma | IL-4r targeting Polylactide NC | Doxorubicin |

| Wang S et al. [27] | U87 GBM | IL-6r targeting Hispolyplex | pING4 |

| Monaco I et al. [30] | U87 GBM | Pdgfrβ targeting Polymeric NC | mTOR inhibitor |

| Fukuta T et al. [37] | MCAO Stroke | Pegylated Liposome | Fasudil |

| Partoazar A et al. [38] | MCAO Stroke | Pegylated Liposome | Cyclosporine A |

| Mann AP et al. [41] | TBI | Peptide targeting Pegylated Au and Si NC | siRNA |

| Sarkar S et al. [47] | AD | Polylactide NC | L-ascorbic acid |

| Pahuja R et al. [48] | 6-OHDA, PD | PLGA NC | Dopamine |

NC=nanocarrier His=histidine, PLGA=poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide), ING4=inhibitor of growth 4, GBM=glioblastoma multiforme, MCAO=middle cerebral artery occlusion, TBI=traumatic brain injury, 6-OHDA=6-hydroxydopamine, PD=parkinson’s disease

Table 2.

| Studies Utilizing Induced BBB Disruption | Neuropathology | Particle Type | Therapeutic Payload |

|---|---|---|---|

| Timbie KF et al. [35] | F98 Glioma | Pegylated Polyaspartic acid | Cisplatin |

| Coluccia D et al. [32] | U251 GBM | Peptide targeting Au NC | Cisplatin |

| Rodríguez-Frutos B et al. [39] | Subcortical Stroke | Lipid Microbubbles | BDNF |

| Wang H-B et al. [40] | MCAO Stroke | Lipid Microbubbles | pVEGF |

| Long L et al. [49] | 6-OHDA, PD | Pegylated Liposomes | pNrf2 |

| Mead BP et al. [34] | 6-OHDA, PD | Pegylated-PEI | pGDNF |

NC=nanocarrier, PEI=poly(ethyleneimine), p=plasmid, BDNF= Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor, Nrf2=nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, GDNF=glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor.

Brain Tumors

Evidence for disruption: The evidence for brain tumors inducing pathologic BBB disruption is complex and can vary by tumor type and from patient to patient[13]. However, several key pieces of data have emerged. First, primary brain tumors exhibit different patterns of BBB disruption than metastatic brain tumors[27]. Second, the entire brain tumor, in either primary or metastatic disease, does not exhibit uniform BBB disruption[13]. Often, the tumor core demonstrates disrupted BBB, but the invasive tumor margin remains behind intact BBB. Finally, different brain tumors exhibit differing levels of disruption[28]. For example, in a mouse presenting with multiple, metastatic brain lesions, only a fraction of tumors exhibit BBB disruption at a given time point[17]. Thus, the extent, as well as complexity of BBB disruption, in brain tumors is an ongoing topic of study. Further, utilizing a pathologic BBB disruption strategy to deliver nanocarriers to brain tumors may require additional strategies that account for tumor regions behind intact BBB.

Pathologic BBB Disruption: The most common example of exploiting pathologic BBB permeability as a therapeutic strategy for treating brain tumors comes from administering nanocarriers displaying only a tumor targeting ligand. Without also harboring a BBB penetrating moiety, nanocarriers administered intravenously likely exhibit significant brain tumor accumulation only at sites of pathologic BBB disruption. Common strategies include administering doxorubicin-loaded or plasmid-loaded nanocarriers modified with peptide or antibodies targeting upregulated interleukin receptors (IL-4, 6 and 13) in rodent orthotopic glioma models[29–31]. The size of the nanocarriers in these studies is approximately 100nm and varied from co-block, self-assembling micelles to pegylated liposomes. In addition, 100nm pegylated liposome nanocarriers loaded with a radioactive isotope (225Ac), and displaying αvβ3 integrin targeting peptide, demonstrate efficacy in a murine model of glioma[32]. Finally, particles displaying targeting motifs for growth factor receptors demonstrated a significant survival benefit as demonstrated in a recent study where polymeric nanocarriers were loaded with a PI3K/mTOR kinase inhibitor and decorated with an aptamer that binds platelet-derived growth factor receptor β (Gint4.T) were used to treat an orthotopic murine brain tumor model[33]. Thus, while these data are open to interpretation of the exact mechanism of tumor delivery, it appears multiple studies demonstrate the feasibility for utilizing pathologic BBB disruption to access the brain tumor site.

Induced BBB Disruption: Both mannitol[34] and more recently, A2A agonist[19], have been used in the context of brain tumors. However, concerns over increased intracranial pressure, and efficacy, have thus far limited the use of these agents. Alternatively, focused ultrasound (FUS) can induce temporary BBB disruption localized to the primary or metastatic brain tumor volume without the use of disruptive chemicals[21,35]. By combining microbubbles with low intensity FUS, BBB disruption is induced via cavitation. This approach contrasts to earlier studies using high intensity ultrasound for thermal tumor ablation[36]. Combining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with FUS allows for precise BBB disruption for approximately 4-6 hours[37]. For example, MRI FUS was used to increase brain tumor uptake of intravenously administered 45nm, cisplatin-containing nanocarriers, modified with PEG chains to increase brain ECM penetration. A significant increase in survival time in rats bearing orthotopic F98 gliomas was observed using the FUS approach[38]. In addition, gold nanoparticles functionalized with a peptide to increase cell uptake (PKKKRKV) and therefore, retention in the tumor volume, were loaded with cisplatin and increased survival in mice bearing orthotopic U251 tumors following FUS[35]. Taken together, delivering nanocarriers via the disrupted brain tumor BBB has been efficacious in preclinical models, particularly when the nanocarriers also possess functionality for enhanced penetration and secondary targeting of tumor epitopes or cell uptake for localized retention.

Stroke

Evidence for disruption: Both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes induce pathologic BBB disruption[11]. While hemorrhagic stroke is by definition a breach of the BBB, ischemic stroke induces BBB disruption in a complex, multi-phasic manner[16]. In ischemic stroke, the BBB becomes disrupted proximal to the site of the clot 4-6 hours after an ischemic event, as evidenced by immunoglobulin leakage and tracer studies. Additionally, animal models and limited human studies suggest the BBB may permeabilize again, or remain open, 48-72 hours following the ischemic event[39].

Pathologic BBB Disruption: Relatively few studies have utilized BBB disruption as a strategy for treating stroke with nanocarriers. Pegylated ~100nm liposome nanocarriers loaded with Fasudil, a Rho-kinase inhibitor, or cyclosporine A, reduced neutrophil invasion and infarct size in rats that underwent transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [40,41]. While the role of the liposomes on pharmacokinetics and increased brain penetration is unclear in these studies, they do suggest the potential utility of exploiting pathologic BBB disruption as a mechanism to deliver nanocarriers to brain regions affected by ischemic stroke.

Induced BBB disruption: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is a protein that demonstrates pleiotropic neuroprotective effects. Mechanical disruption of the BBB using FUS in concert with BDNF-loaded microbubbles results in increased BDNF levels within damaged white matter and improved functional outcomes in rat model of subcortical stroke compared to non-FUS or non-BDNF treated controls[42]. Similarly, delivery of microbubbles loaded with plasmid encoding vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) resulted in decreased infarct areas in murine stroke models following FUS[43]. Thus, post-stroke administration of nanocarriers loaded with therapeutic proteins could be enhanced by FUS, resulting in reduced reperfusion injury.

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

Evidence for disruption: TBI is broadly used to describe any acute incident that causes damage to brain tissue[12]. Generally this is due to laceration from a stab wound or hemorrhage resulting from impact of the brain on the skull as in a concussive event[44]. Studies demonstrate substantial BBB disruption using tracers and brain accumulation of blood components at the sites of stab or impact wound models[45].

Pathologic BBB Disruption: In mice with impact cranial wounds, radiolabeled, 82nm pegylated liposomes accumulated significantly at the injury site compared to contralateral brain in the same mouse[46], demonstrating pathologic BBB disruption as a viable mechanism for nanocarrier access to TBI sites. Additionally, a short peptide sequence (CAQK) was identified that could be used to target pegylated 20nm silver and 150nm silicon nanoparticles to the injured mouse brain ECM induced by TBI[44]. Importantly, the CAQK peptide sequence targeted nanoparticles to sites of TBI in both impact and lacerating murine models. Thus, pathologic BBB disruption can serve as a mechanism to access a TBI injury site for nanocarrier-based therapies.

Induced BBB Disruption: Neither chemical nor mechanical mechanisms to induce BBB disruption are frequently used in the context of TBI. This may be due, in part, to the clear breaches of brain vasculature that are a hallmark of TBI. Additionally, a primary clinical concern is normalizing intracranial pressure which could be negatively impacted by additional BBB disruption in TBI[47].

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Evidence for disruption for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: The strongest evidence that Alzheimer’s (AD) patients have a disrupted BBB is elevated CSF/plasma albumin levels in AD patients[14]. However, only a subset of patients exhibited an elevated CSF albumin ratio. Additionally, gadolinium enhanced MRI imaging studies of AD patients do not demonstrate enhanced sites of BBB leakage compared to age matched controls[48]. However, the gadolinium imaging study of BBB disruption in AD patients did observe a correlation between BBB disruption and AD progression. Thus, the extent of BBB disruption in AD remains controversial, and warrants further investigation.

Similar to AD, evidence that Parkinson’s (PD) induces pathologic BBB disruption primarily derives from patients exhibiting an elevated CSF/plasma albumin ratio[15]. Interestingly, the effect is only observed in patients with advanced disease, suggesting that BBB disruption in PD may also be correlated with disease progression. Therefore, the degree of BBB disruption in AD and PD remains unclear, and the success of a nanocarrier delivery strategy leveraging BBB disruption may vary significantly based on disease severity at time of administration[49].

Pathologic BBB Disruption: A few studies have attempted to exploit pathologic BBB disruption to deliver therapeutic nanocarriers to treat either AD or PD. Administering polylactide nanocarriers containing L-ascorbic acid resulted in reduced ROS damage in murine AD model[50]. Similarly, administration of PLGA nanoparticles loaded with dopamine reduced dopaminergic neuron degeneration in a rat model of PD[51]. However, as these studies utilized non-targeted or modified nanocarriers, it is unclear whether the efficacy resulted from increased delivery due to pathologic BBB disruption or well-known, beneficial pharmacokinetic (PK) alterations provided by nanocarriers.

Induced BBB Disruption: Multiple studies with the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) rat PD model demonstrate the benefit of utilizing FUS coupled with microbubbles to mechanically disrupt the BBB. Intravenous administration of microbubbles encapsulating plasmid encoding for nuclear factor E2-reated factor 2 (NRF2) coupled with FUS reduced neuronal death in 6-OHDA rat PD model[52]. Additionally, coupling FUS with 50nm pegylated liposome nanocarrier containing plasmid encoding glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) restored dopaminergic neuron density in rat PD model compared to liposomes loaded with control plasmid[37]. Thus, mechanical disruption of BBB could be an approach for facilitating nanocarrier delivery and diffusion in PD affected brain regions, and perhaps could be extended to other neurodegenerative diseases like AD.

Conclusion

The healthy BBB prevents nanocarriers from accessing the CNS, thereby hampering delivery of therapeutic cargo. However, certain neurological diseases induce pathologic BBB disruption that may allow nanocarrier access to the diseased site. Utilizing pathologically-disrupted BBB to deliver nanocarriers loaded with therapeutic small molecules, nucleic acids, or proteins to the diseased CNS remains an underdeveloped approach for many neuropathologies. Moreover, inducing BBB disruption through FUS technologies can augment pathological BBB disruption for nanocarrier accumulation in diseased brain. The nanomedicine field is clearly beginning to apply designer nanocarriers in the context of several different neurological diseases. In particular, nanocarriers have been designed to better penetrate the complex CNS microenvironment and potentially increase uniform distribution of therapeutic proteins throughout the targeted pathology[8]. Nanocarriers designed to specifically target CNS structures in the postvascular brain such as tumor cells or extracellular matrix would enhance the retention of nanocarriers to act as a depot for protein-based therapeutics. Combining the improvements in nanocarrier penetration and retention should prove to increase the therapeutic potency of small molecules, nucleic acid and/or proteins that are loaded into nanocarriers. Future studies focused on developing new targeting ligands specifically designed to accumulate at sites of pathologic BBB disruption could offer improvements in exploiting this strategy. Additionally, modification of particle size could enhance retention[8], while using hot and cold ligand strategies could enhance penetration of therapeutic nanocarriers into the diseased tissue[25,26,53]. Approaches that increase penetration may be especially important for diseases like brain tumors where portions of the tumor at the invasive margins lie behind an intact BBB. Finally, further understanding of the timing and extent of pathologic BBB disruption could allow for the customization of targeted nanocarriers to augment existing disease therapies.

Highlights:

Highlights pathologic BBB disruption in acute and chronic CNS disease.

Identifies approaches that use pathologic and induced BBB disruption to facilitate nanocarrier delivery to diseased brain.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant NS099158 (E.V.S.), and a Falk Medical Research Trust Catalyst Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, Yusof SR, Begley DJ: Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis. 2010, 37:13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fang F, Zou D, Wang W, Yin Y, Yin T, Hao S, Wang B, Wang G, Wang Y: Non-invasive approaches for drug delivery to the brain based on the receptor mediated transport. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 2017, 76:1316–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CE, Alizadeh D, Starr R, Weng L, Wagner JR, Naranjo A, Ostberg JR, Blanchard MS, Kilpatrick J, Simpson J, et al. : Regression of Glioblastoma after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375:2561–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan AR, Liu M, Khan MW, Zhai G: Progress in brain targeting drug delivery system by nasal route. J Control Release 2017, 268:364–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lonser RR, Sarntinoranont M, Morrison PF, Oldfield EH: Convection-enhanced delivery to the central nervous system. J. Neurosurg. 2015, 122:697–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulatis LI, Shusta EV: Protein engineering approaches for regulating blood-brain barrier transcytosis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2017,45:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govender T, Choonara YE, Kumar P, Bijukumar D, Toit du LC, Modi G, Naidoo D, Pillay V: Implantable and transdermal polymeric drug delivery technologies for the treatment of central nervous system disorders. Pharm Dev Technol 2017, 22:476–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mastorakos P, Zhang C, Berry S, Oh Y, Lee S, Eberhart CG, Woodworth GF, Suk JS, Hanes J: Highly PEGylated DNA Nanoparticles Provide Uniform and Widespread Gene Transfer in the Brain. Adv Healthc Mater 2015,4:1023–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies A, Lewis DJ, Watson SP, Thomas SG, Pikramenou Z: pH-controlled delivery of luminescent europium coated nanoparticles into platelets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012,109:1862–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagliardi M, Borri C: Polymer Nanoparticles as Smart Carriers for the Enhanced Release of Therapeutic Agents to the CNS. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017,23:393–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadeau CA, Dietrich K, Wilkinson CM, Crawford AM, George GN, Nichol HK, Colbourne F: Prolonged Blood-Brain Barrier Injury Occurs After Experimental Intracerebral Hemorrhage and Is Not Acutely Associated with Additional Bleeding. TransI Stroke Res 2018, June 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appenteng R, Nelp T, Abdelgadir J, Weledji N, Haglund M, Smith E, Obiga 0, Sakita FM, Miguel EA, Vissoci CM, et al. : A systematic review and quality analysis of pediatric traumatic brain injury clinical practice guidelines. PLoS ONE 2018,13:e0201550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockman PR, Mittapalli RK, Taskar KS, Rudraraju V, Gril B, Bohn KA, Adkins CE, Roberts A, Thorsheim HR, Gaasch JA, et al. : Heterogeneous blood-tumor barrier permeability determines drug efficacy in experimental brain metastases of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010,16:5664–5678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Algotsson A, Winblad B: The integrity of the blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2007,115:403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisani V, Stefani A, Pierantozzi M, Natoli S, Stanzione P, Franciotta D, Pisani A: Increased blood-cerebrospinal fluid transfer of albumin in advanced Parkinson’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2012, 9:188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prakash R, Carmichael ST: Blood-brain barrier breakdown and neovascularization processes after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2015, 28:556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyle LT, Lockman PR, Adkins CE, Mohammad AS, Sechrest E, Hua E, Palmieri D, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Kloc W, et al. : Alterations in Pericyte Subpopulations Are Associated with Elevated Blood-Tumor Barrier Permeability in Experimental Brain Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22:5287–5299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberoi RK, Parrish KE, Sio TT, Mittapalli RK, Elmquist WF, Sarkaria JN: Strategies to improve delivery of anticancer drugs across the blood- brain barrier to treat glioblastoma. Neuro-oncology 2016,18:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson S, Weingart J, Nduom EK, Harfi TT, George RT, McAreavey D, Ye X, Anders NM, Peer C, Figg WD, et al. : The effect of an adenosine A2A agonist on intra-tumoral concentrations of temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Fluids Barriers CNS 2018,15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lamsam L, Johnson E, Connolly ID, Wintermark M, Hayden Gephart M: A review of potential applications of MR-guided focused ultrasound for targeting brain tumor therapy. Neurosurg Focus 2018,44:E10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baghirov H, Snipstad S, Sulheim E, Berg S, Hansen R, Thorsen F, Mørch Y, Davies C de L, Åslund AKO: Ultrasound-mediated delivery and distribution of polymeric nanoparticles in the normal brain parenchyma of a metastatic brain tumour model. PLoS ONE 2018,13:e0191102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szablowski JO, Lee-Gosselin A, Lue B, Malounda D, Shapiro MG: Acoustically targeted chemogenetics for the non-invasive control of neural circuits. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2018, 2:475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang R, Harmsen S, Samii JM, Karabeber H, Pitter KL, Holland EC, Kircher MF: High Precision Imaging of Microscopic Spread of Glioblastoma with a Targeted Ultrasensitive SERRS Molecular Imaging Probe. Theranostics 2016,6:1075–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hua M-Y, Liu H-L, Yang H-W, Chen P-Y, Tsai R-Y, Huang C-Y, Tseng I-C, Lyu L-L, Ma C-C, Tang H-J, et al. : The effectiveness of a magnetic nanoparticle- based delivery system for BCNU in the treatment of gliomas. Biomaterials 2011,32:516–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Telano LN, Baker S: Physiology, Cerebral Spinal Fluid (CSF). StatPearls Publishing; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolak DJ, Thorne RG: Diffusion of macromolecules in the brain: implications for drug delivery. Mol Pharm. 2013,10:1492–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terrell-Hall TB, Nounou MI, El-Amrawy F, Griffith JIG, Lockman PR: Trastuzumab distribution in an in-vivo and in-vitro model of brain metastases of breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8:83734–83744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarkaria JN, Hu LS, Parney IF, Pafundi DH, Brinkmann DH, Laack NN, Giannini C, Burns TC, Kizilbash SH, Laramy JK, et al. : Is the blood-brain barrier really disrupted in all glioblastomas? A critical assessment of existing clinical data. Neuro-oncology 2018, 20:184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •[29].Sun Z, Yan X, Liu Y, Huang L, Kong C, Qu X, Wang M, Gao R, Qin H: Application of dual targeting drug delivery system for the improvement of anti-glioma efficacy of doxorubicin. Oncotarget 2017, 8:58823–58834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (Sattiraju A et al.) The authors generated liposomes displaying an αvβ3 targeting motif and loaded particles with an alpha emitter for GBM therapy. Intravenous administration of particles resulted in significant tumor response.

- •[30].Wang S, Reinhard S, Li C, Qian M, Jiang H, Du Y, Lachelt U, Lu W, Wagner E, Huang R: Antitumoral Cascade-Targeting Ligand for IL-6 Receptor-Mediated Gene Delivery to Glioma. Molecular Therapy 2017, 25:1556–1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (Monaco I et al.) This study immobilized an aptamer designed to target PDGFrβ onto polymeric nanoparticles and delivered dual PI3K/mTOR kinase inhibitor to an orthotopic brain tumor using intravenous administration.

- 31.Madhankumar AB, Slagle-Webb B, Wang X, Yang QX, Antonetti DA, Miller PA, Sheehan JM, Connor JR: Efficacy of interleukin-13 receptor-targeted liposomal doxorubicin in the intracranial brain tumor model. Mol Cancer Ther 2009, 8:648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sattiraju A, Xiong X, Pandya DN, Wadas TJ, Xuan A, Sun Y, Jung Y, Sai KKS, Dorsey JF, Li KC, et al. : Alpha Particle Enhanced Blood Brain/Tumor Barrier Permeabilization in Glioblastomas Using Integrin Alpha-v Beta-3-Targeted Liposomes. Mol Cancer Ther 2017,16:2191–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monaco I, Camorani S, Colecchia D, Locatelli E, Calandro P, Oudin A, Niclou S, Arra C, Chiariello M, Cerchia L, et al. : Aptamer Functionalization of Nanosystems for Glioblastoma Targeting through the Blood-Brain Barrier. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60:4510–4516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palma L, Bruni G, Fiaschi AI, Mariottini A: Passage of mannitol into the brain around gliomas: a potential cause of rebound phenomenon. A study on 21 patients. J Neurosurg Sci 2006, 50:63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coluccia D, Figueiredo CA, Wu MY, Riemenschneider AN, Diaz R, Luck A, Smith C, Das S, Ackerley C, O’Reilly M, et al. : Enhancing glioblastoma treatment using cisplatin-gold-nanoparticle conjugates and targeted delivery with magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound. Nanomedicine 2018, 14:1137–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauri G, Nicosia L, Xu Z, Di Pietro S, Monfardini L, Bonomo G, Varano GM, Prada F, Vigna Della P, Orsi F: Focused ultrasound: tumour ablation and its potential to enhance immunological therapy to cancer. BrJ Radiol 2018, 91:20170641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mead BP, Kim N, Miller GW, Hodges D, Mastorakos P, Klibanov AL, Mandell JW, Hirsh J, Suk JS, Hanes J, et al. : Novel Focused Ultrasound Gene Therapy Approach Noninvasively Restores Dopaminergic Neuron Function in a Rat Parkinson’s Disease Model. Nano Lett. 2017,17:3533–3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timbie KF, Afzal U, Date A, Zhang C, Song J, Wilson Miller G, Suk JS, Hanes J, Price RJ: MR image-guided delivery of cisplatin-loaded brain-penetrating nanoparticles to invasive glioma with focused ultrasound. J Control Release 2017, 263:120–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Rosenberg GA: Blood-brain barrier breakdown in acute and chronic cerebrovascular disease. Stroke 2011, 42:3323–3328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukuta T, Asai T, Sato A, Namba M, Yanagida Y, Kikuchi T, Koide H, Shimizu K, Oku N: Neuroprotection against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by intravenous administration of liposomal fasudil. Int J Pharm 2016, 506:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ••[41].Partoazar A, Nasoohi S, Rezayat SM, Gilani K, Mehr SE, Amani A, Rahimi N, Dehpour AR: Nanoliposome containing cyclosporine A reduced neuroinflammation responses and improved neurological activities in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rat. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2017, 31:185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (Mann AP et al.) This study utilized in vivo phage display to identify a short peptide that accumulates in TBI-induced ECM. The peptide targets several types of nanoparticles to the injury site following intravenous administration.

- 42.Rodríguez-Frutos B, Otero-Ortega L, Ramos-Cejudo J, Martínez-Sánchez P, Barahona-Sanz I, Navarro-Hernanz T, Gómez-de Frutos MDC, Díez-Tejedor E, Gutéerrez-Fernández M: Enhanced brain-derived neurotrophic factor delivery by ultrasound and microbubbles promotes white matter repair after stroke. Biomaterials 2016,100:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H-B, Yang L, Wu J, Sun L, Wu J, Tian H, Weisel RD, Li R-K: Reduced ischemic injury after stroke in mice by angiogenic gene delivery via ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction. J. Neuropathol Exp. Neurol. 2014,73:548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann AP, Scodeller P, Hussain S, Joo J, Kwon E, Braun GB, Mölder T, She Z-G, Kotamraju VR, Ranscht B, et al. : A peptide for targeted, systemic delivery of imaging and therapeutic compounds into acute brain injuries. Nat Commun 2016, 7:11980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li W, Long JA, Watts LT, Jiang Z, Shen Q, Li Y, Duong TQ: A quantitative MRI method for imaging blood-brain barrier leakage in experimental traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2014, 9:ell4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boyd BJ, Galle A, Daglas M, Rosenfeld JV, Medcalf R: Traumatic brain injury opens blood-brain barrier to stealth liposomes via an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR)-like effect. J Drug Target 2015, 23:847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- •[47].Alnemari AM, Krafcik BM, Mansour TR, Gaudin D: A Comparison of Pharmacologic Therapeutic Agents Used for the Reduction of Intracranial Pressure After Traumatic Brain Injury. World Neurosurg 2017,106:509–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (Sarkar S et al.) Here the authors loaded L-ascorbic acid into polylactide nanocapsules and demonstrated reduced ROS damage in AD model following systemic administration of particles.

- •[48].Starr JM, Farrall AJ, Armitage P, McGurn B, Wardlaw J: Blood-brain barrier permeability in Alzheimer’s disease: a case-control MRI study. Psychiatry Res 2009,171:232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (Pahuja R et al.) The study immobilized dopamine onto PLGA nanoparticles that were administered intravenously. Treated PD model rats demonstrated increased dopaminergic neuron density compared to controls.

- 49.Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV: Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2018,14:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sarkar S, Mukherjee A, Swarnakar S, Das N: Nanocapsulated Ascorbic Acid in Combating Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion- Induced Oxidative Injury in Rat Brain. Curr Alzheimer Res 2016,13:1363–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pahuja R, Seth K, Shukla A, Shukla RK, Bhatnagar P, Chauhan LKS, Saxena PN, Arun J, Chaudhari BP, Patel DK, et al. : Trans-blood brain barrier delivery of dopamine-loaded nanoparticles reverses functional deficits in parkinsonian rats. ACS Nano 2015, 9:4850–4871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Long L, Cai X, Guo R, Wang P, Wu L, Yin T, Liao S, Lu Z: Treatment of Parkinson’s disease in rats by Nrf2 transfection using MRI-guided focused ultrasound delivery of nanomicrobubbles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2017, 482:75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cilliers C, Menezes B, Nessler I, Linderman J, Thurber GM: Improved Tumor Penetration and Single-Cell Targeting of Antibody-Drug Conjugates Increases Anticancer Efficacy and Host Survival. Cancer Res. 2018, 78:758–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]