Abstract

The term Blue Carbon (BC) was first coined a decade ago to describe the disproportionately large contribution of coastal vegetated ecosystems to global carbon sequestration. The role of BC in climate change mitigation and adaptation has now reached international prominence. To help prioritise future research, we assembled leading experts in the field to agree upon the top-ten pending questions in BC science. Understanding how climate change affects carbon accumulation in mature BC ecosystems and during their restoration was a high priority. Controversial questions included the role of carbonate and macroalgae in BC cycling, and the degree to which greenhouse gases are released following disturbance of BC ecosystems. Scientists seek improved precision of the extent of BC ecosystems; techniques to determine BC provenance; understanding of the factors that influence sequestration in BC ecosystems, with the corresponding value of BC; and the management actions that are effective in enhancing this value. Overall this overview provides a comprehensive road map for the coming decades on future research in BC science.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Plant sciences, Biogeochemistry

The role of Blue Carbon in climate change mitigation and adaptation has now reached international prominence. Here the authors identified the top-ten unresolved questions in the field and find that most questions relate to the precise role blue carbon can play in mitigating climate change and the most effective management actions in maximising this.

Introduction

Blue Carbon (BC) refers to organic carbon that is captured and stored by the oceans and coastal ecosystems, particularly by vegetated coastal ecosystems: seagrass meadows, tidal marshes, and mangrove forests. Global interest in BC is rooted in its potential to mitigate climate change while achieving co-benefits, such as coastal protection and fisheries enhancement1–3. BC has attracted the attention of a diverse group of actors beyond the scientific community, including conservation and private sector organizations, governments, and intergovernmental bodies committed to marine conservation and climate change mitigation and adaptation. The momentum provided by these conservation and policy actors has energized the scientific community by challenging them to address knowledge gaps and uncertainties required to inform policy and management actions.

The BC concept was introduced as a metaphor aimed at highlighting that coastal ecosystems, in addition to terrestrial forests (coined as green carbon), contribute significantly to organic carbon (C) sequestration1. This initial metaphor evolved to encompass strategies to mitigate and adapt to climate change through the conservation and restoration of vegetated coastal ecosystems1,2. As BC science consolidates as a paradigm, some aspects are still controversial; for instance, contrasting perspectives on the role of carbonate production as a component of BC4 and whether seaweed contributes to BC5,6. We propose an open discussion to refocus the current research agenda, reconcile new ideas with criticisms, and integrate those findings into a stronger scientific framework (Box 1). This effort will address the urgent need for refined understanding of the role of vegetated coastal ecosystems in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

There is, therefore, a need to establish a comprehensive research program on BC science that addresses current gaps while continuing to respond to immediate policy and managerial needs. Furthermore, this research program can inform policy directions based on new knowledge, thus playing a role in setting the management agenda and not simply responding to it. Here we identify, based on a broad effort by the leading research academics in BC science, key questions and challenges that need to be addressed to consolidate progress in BC science and inform current debate. We do so through three main steps. First, we briefly summarize the elements of BC science that represent the pillar of this research program. Second, we identify key scientific questions by first surveying the scientific community. Then we clustered these questions into common themes, which develop research goals and agendas. Last, we provide guidance as to how these questions can be best articulated into a new research agenda as a path for progress.

Box 1. Evidence underpinning the science.

The role of seagrasses and marine macroalgae as major C sinks in the ocean was first proposed by Smith who suggested that seagrasses and marine macroalgae were overlooked C sinks7; however, at the time, there was minimal uptake of the concept within climate change mitigation efforts. In 2003 the first global budget of C storage in soils of salt marshes and mangroves brought light to the importance of these coastal ocean sink. By 2005, it was shown that seagrass, mangrove, and tidal marsh sediments represent 50% of all C sequestered in marine sediments8. This mounting evidence for such a major role in C sequestration provided the impetus for the Blue Carbon report1, where the term “Blue Carbon” was first coined, and that led to the development of international and national BC initiatives (e.g., http://thebluecarboninitiative.org). This led to research efforts to propose emissions factors from loss and restoration of BC ecosystems for C accounting9, provide empirical evidence of emissions following disturbance and C drawdown from restoration10,11,12, map the C density of mangrove soils globally13, and explore the potential of BC ecosystems to support climate-change adaptation2.

Scientists’ perspectives on the 10 key fundamental questions in BC science

We identified and selected scientists from among the leading and senior authors of the 50 most-cited papers on BC science (ISI Web of Science access date 22 June 2017), together with the participants in a workshop on BC organized at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Saudi Arabia, in March 2017. We did not attempt to identify any scientists’ area of specialisation to avoid bias. Among these authors, we surveyed those affiliated with academic or research institutions. A group of 50 scientists were asked to contribute from their perspective the top pending questions (up to 10) in BC science. Specifically, the invitees were asked to “Email your ten most important questions (or fewer) relevant to improving our understanding of blue carbon science and its application to climate change mitigation”. We did not ask scientists to prioritise their questions, or target any particular geographical area, but we did ask them to focus on mangrove, tidal marsh, macroalgal, and seagrass ecosystems. The answers received (35 total respondents, see Supplementary Note 1) and were then clustered into ten themes (by grouping questions that were similar) that were subsequently articulated into individual, overarching research questions:

Q1. How does climate change impact carbon accumulation in mature Blue Carbon ecosystems and during their restoration?

The impacts of climate change on BC ecosystems and their C stocks are dependent on the exposure to climate change factors. This is influenced by both the frequency and intensity of stressors, and the sensitivity and resilience of the ecosystem14. Question 1 reflects uncertainties associated with the rate and magnitude of climate change15–17 as well as uncertainties about the impacts of climate change on current and restored BC ecosystems, their rates of C sequestration and the stability of C stocks, which are likely to vary with past sea level history18, over geographic locations, among BC ecosystems, and within ecosystems.

BC ecosystems mainly occupy the intertidal and shallow water environments, where their distribution, productivity and rates of vertical accretion of soils are strongly influenced by sea level19,20 and the space available to accumulate sediment21. Thus, sea level rise ranks among the most important factors that will influence future BC stocks and sequestration. Sea level rise can result in BC gains, with increasing landward areal extent of ecosystems where possible22, and enhanced vertical accretion of sediments and C stocks18,23; and losses, with losses of ecosystem extent24, failure of restoration25, remineralization of stored organic matter26 that result in greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere (Table 1). Intense storms17, marine heat waves, 27, elevated CO228, and altered availability of freshwater29 have also all been implicated as important factors affecting the distribution, productivity, community composition and C sequestration of BC ecosystems over a range of locations (Table 1). Geographic variation in exposure to climate change is high. Rates of sea level rise and land subsidence30, which enhances relative rates of sea level rise, vary geographically18. Additionally, rates of temperature change and changes in the frequency of intense storms and rainfall vary regionally15–17. Geomorphic models have provided first pass assessments of the global vulnerability of BC ecosystems to sea level rise20,31, and for restoration success32, but local scale descriptors of changes in exposure of BC ecosystems to climate change and impacts on C stocks are often incomplete or missing. For instance, storm associated waves are important for determining the persistence and recruitment of BC ecosystem33, yet local assessments are not widely available.

Table 1.

Examples of gains and losses for BC stocks with a range of climate change factors

| Ecosystem | Sea level rise | Extreme storms | Higher temperatures | Extra CO2 | Altered precipitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mangrove |

Landward expansion increases area and C stocks Losses of low intertidal forests and coastal squeeze could reduce C stocks Increasing accommodation space increases C sequestration |

Canopy damage, reduced recruitment and soil subsidence resulting in losses of C stocks Soil elevation gains due to sediment deposition increasing C stocks and, reducing effects of sea level rise |

Minimal impacts anticipated, although increased decomposition of soil C possible Poleward spread of mangrove forests at expense of tidal marshes increases C stocks Change in dominant species could influence C sequestration |

An increase in atmospheric CO2 benefits plant productivity of some species which could alter C stocks |

Canopy dieback due to drought Losses of C stocks due to remineralization and reduced productivity Increased rainfall may result in increased productivity and C sequestration |

| Tidal Marsh |

Landward expansion increased area and C stocks Losses of low intertidal marsh and coastal squeeze could reduce C stocks Increasing accommodation space increases C sequestration |

Loss of marsh area and C stocks Enhanced sedimentation and soil elevation increasing C stocks and, reducing effects of sea level rise |

Increased temperatures may increase decomposition of soil organic matter, but offset by increased productivity of tidal marsh vegetation Poleward expansion of mangroves will replace tidal marsh and increase C storage Poleward expansion of bioturbators, may decrease soil C stocks |

An increase in atmospheric CO2 benefits plant productivity of some species which could alter C stocks |

Reduced above and belowground production due to drought reducing C sequestration Possible losses of C stocks due to remineralization Impact could be greater in areas that already have scarce or variable rainfall |

| Seagrass |

Loss of deep water seagrass Landward migration in areas where seawater floods the land (into mangrove or tidal marsh ecosystem) |

Some extreme storms cause the erosion of seagrasses and loss of seagrass C stocks but some seagrass species are resistant to these major events Flood events associated with extreme rainfall may result in mortality, but could also increase sediment accretion and C sequestration |

Thermal die-offs leading to losses of C stocks Species turnover Colonization of new poleward regions Increased productivity |

An increase in dissolved inorganic C benefits plant productivity increasing C stocks Ocean acidification leads to loss of seagrass biodiversity, decreasing C stocks |

Most seagrasses are tolerant of acute low salinity events associated with high rainfall, but some are negatively affected and potential interactions with disease may lead to losses of C stocks Reduced rainfall increases light availability which increases productivity and C sequestration |

| Seaweed |

Loss of deep water seaweeds Seaweeds are expected to colonise hard substrata that become flooded, increasing C stocks |

Reduces seaweed cover, but could lead to sequestration of C stocks as detritus sinks |

Major retraction in kelp forest C stores at non-polar range edges; Expected expansion at polar range edges. |

Increased biomass and productivity of kelp where water temperatures remain cool enough |

Little effect overall Regional effects on seaweed flora in areas with high land run off/rivers |

Bold text indicate potential positive effects on BC stocks, italic text indicate negative effects with roman text indicating where effects could be positive or negative

Responses of adjacent ecosystems to climate change may influence the exposure and sensitivity of BC ecosystems and their C stocks to climate change. For example, degradation of coral reefs could increase wave heights within lagoons which may lead to losses of seagrass or mangroves within lagoons with rising sea levels as waves increase34, or decreases of carbonate sediments due to ocean acidification, may reduce the ability of some BC ecosystems to keep up with sea level rise35. Additionally, the sensitivity of BC ecosystems to climate change is also likely influenced by human activities in the coastal zone. For example, deterioration in water quality may increase the impacts of sea level rise on seagrass36 and decreased sedimentation from damming of rivers, hydrological modifications and presence of seawalls may negatively affect BC stocks in mangroves and tidal marshes20,31.

Q2. How does disturbance affect the burial fate of Blue Carbon?

The effect of disturbance on BC production and storage has become a topic of intense interest because of an increasing desire to protect or enhance this climate-related ecosystem service. There are three key issues, all beginning to be addressed by BC researchers, but requiring further study: (1) the depth in the soil profile to which the disturbance propagates, (2) the proportion of disturbed C that is lost as CO2, and (3) the extent to which issues 1 and 2 are context dependent. The first global estimates of potential losses of BC resulting from anthropogenic disturbance combined changes in the global distribution of BC ecosystems with simple estimates of conversion (remineralisation) of stored BC per unit area37. The estimated annual CO2 emission from the disturbance of BC ecosystems was estimated at 0.45 Petagrams CO2 globally37. The generalised assumptions necessary for such global assessments—e.g., remineralization within only the top 1 m of soil, and 100% loss of BC—provide little guidance at a local management scale and gloss over the variability of effects from different disturbance types38. This deficiency has led to a more nuanced theoretical framework accounting for the intensity of disturbance, especially whether the disturbance affects only the habitat-forming plant (e.g., clearing, eutrophication, light reduction, toxicity) or whether it also disturbs the soil (e.g., erosion, digging, reclamation)39,40. The duration of disturbance is another important predictor of disturbance effects on BC remineralisation because, over time, more soil BC is exposed to an oxic environment41.

We have a nascent understanding of the processes by which natural and human disturbances alter C decomposition. Die-off of below-ground roots and rhizomes in tidal marshes, for example, changes the chemical composition of BC and associated microbial assemblages, subsequently increasing decomposition and decreasing stored C (by up to 90% (ref. 42)). In seagrass ecosystems, exposing deeply buried sediments to oxygen triggered microbial breakdown of ancient BC43. At this stage, there is some evidence that disturbances can diminish BC stocks, for example: oil spills44, seasonal wrack deposition42, aquaculture45, eutrophication46, altered tidal flows46, and harvesting of fisheries resources38,47. Such knowledge is key for the construction of Emissions Factors for modelling. But examples in the literature are often specific for a particular disturbance or ecosystem setting, and do not yet offer the generalised understanding necessary to build a comprehensive framework guiding management projects. Finally, although there is widespread agreement that a changing climate directly affects BC production and storage, we recommend a clearer focus on the interacting effects of climate and direct anthropogenic disturbances.

Q3. What is the global importance of macroalgae, including calcifying algae, as Blue Carbon sinks/donors?

Macroalgae are highly productive (Table 2) and have the largest global area of any vegetated coastal ecosystem48. Yet only in a relatively few cases have macroalgae been included in BC assessments. Unlike angiosperms, which grow on depositional soils2, macroalgae generally grow on hard or sandy substrata that have no or only limited C burial potential6. However, a recent meta-analysis has estimated that macroalgae growing in soft sediments have a global C burial rate of 6.2 Tg C yr−1 (ref. 6), which is comparable to the lower range of estimates for tidal marshes. Furthermore, several studies show that macroalgae act as C donors3,6,49–51, where detached macroalgae are transported by currents, and deposited in C sinks beyond macroalgae habitats. Recent first-order estimates have suggested that up to 14 Tg C yr−1 of macroalgae-derived particulate organic C is buried in shelf sediments and an additional 153 Tg C yr−1 is sequestered in the deep ocean6. These calculations suggest that macroalgae may be supporting higher global C burial rates than seagrass, tidal marshes, and mangroves combined. This research highlights that if we are to incorporate macroalgal systems into BC assessments we need a better understanding of the fate of C originating from these systems. Furthermore, if we are to scale up from local measurements of C-sequestration to the global level, more refined estimates of the global surface area of macroalgal-dominated systems are needed.

Table 2.

Estimates of global net primary productivity, CO2 release from calcification and C sequestration (Tg C yr−1) for three benthic marine systems

| System | Global CO2 (as C) fixation in NPP | Global CO2 (as C) release from calcification, assuming 0.6 CO2-C per CaCO3-C produced | Global net organic C assimilation = NPP minus C as CO2 produced in calcification | Global C sequestration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benthic macroalgae (calcified and uncalcified) | 960–2000 | – | – | 60–1400 | Charpy-Roubard & Sournia71; Krause-Jensen & Duarte6; Duarte49; Raven50 |

| Calcified coralline red algae | 720 | 120 | 600 | – | Van den Heijden & Kamenos53, who do not mention CO2 release from CaCO3 formation |

| Coral reefs | 0 | 84–840 | 84–840 | 0a | Ware et al.150; Smith & Mackenzie151 |

aAssuming CaCO3 ultimately sinks below the lysocline, where CaCO3 dissolves, and upwelling ultimately (102–103 years) brings the resulting HCO3− back to the sea surface

Most estimates of C-sequestration by marine vegetated ecosystems refer solely to organic C even though calcifying organisms are also important components of such ecosystems52. For calcifying algae, whether they serve as C-sinks or sources is debated4, especially where calcifying organisms form and become buried within seagrass meadows4,5. Carbonate production results in the release of 0.6 mol of CO2 per mol of CaCO3 precipitated53, suggesting that calcifying algae are sources of CO2 that counteract C-sequestration in these ecosystems. However, co-deposition of organic and inorganic C may also have interacting effects on C-sequestration4. Carbonate may help protect and consolidate organic C sediment deposits, and CO2 release from mineralization of organic matter may stimulate carbonate dissolution and hence, CO2 removal48,53,54. Burial of inorganic carbon in seagrass and mangrove ecosystems is also to a large extent supported by inputs from adjacent ecosystems rather than by local calcification. Furthermore, mass balances highlight that such Blue Carbon ecosystems are sites of net CaCO3 dissolution54. More studies are needed to assess the net effect of organic and inorganic C deposition on C sequestration in calcifying systems.

Q4. What is the global extent and temporal distribution of BC ecosystems?

Our attempts to upscale BC estimates and model changes across large spatial and temporal scales is hindered by poor knowledge of their current and recent-past global distributions. The best constrained areal estimates exist for mangroves, which occur in tropical and subtropical regions, generally where winter seawater isotherms exceed 20 °C55. Overall, the global spatial extent of mangroves, and patterns and drivers of their temporal change, are relatively well understood, especially when compared with other BC ecosystems. Still, Giri et al.56 estimated a global area of mangroves of ca. 140,000 km2 in the year 2000 and Hamilton and Casey57 83,495 km2 in 2000 and 81,849 km2 in 2012. Both studies used Landsat data but different methodologies. Mangroves occur in 118 countries worldwide, but ~75% of total coverage is located within just 15 countries, with ~23% found in Indonesia alone56. Total mangrove extent during the second half of the 20th century declined at rates 1–3% yr−1 mainly due to aquaculture, land use change and land reclamation58. There are uncertainties in the area of mangrove that are scrub forms and which are therefore often not considered as forests despite their importance in arid and oligotrophic settings and often their large soil C stocks59,60. Since the beginning of the 21st century, mangrove loss rates are 0.16–0.39% yr−1 (ref. 57), probably reflecting changes in aquaculture and conservation efforts.

Tidal marshes are primarily found in estuaries along coasts of Arctic, temperate and subtropical coastal lagoons, embayments, and low-energy open coasts, although they also occur in some tropical regions61. Woodwell et al.62 estimated global tidal marsh extent of 380,000 km2 using the fraction of global coastline occupied by estuaries and the assumption that ~20% of estuaries supported tidal marshes48. However, tidal marsh area has been mapped in only 43 countries (yielding a total habitat extent of ca. 55,000 km2), which represents just 14% of the potential global area63. Tidal marsh extent is well documented for Canada, Europe, USA, South Africa and Australia63–65 but remains unknown to a large extent in regions, including Northern Russia and South America. An historical assessment of 12 estuaries and coastal seas worldwide indicated that >60% of wetland coverage has been lost66 mostly due to changes in land use, coastal transformation and land reclamation61. The minimum global rate of loss of tidal marsh area is estimated at 1–2% yr−1 (ref. 67).

Despite the widespread occurrence of seagrass across both temperate and tropical regions, the global extent of seagrass area is poorly estimated48. The total global area was recently updated to 350,000 km2 (ref. 68), although estimates range from 300,000 (ref.) to 600,000 km2 (ref. 69), with a potential habitable area for seagrass of 4.32 million km2 (ref. 70). Available distribution data are geographically and historically biased, reflecting the imbalance in research effort among regions71, and most data have been collected since the 1980s72. The total global seagrass area has decreased by ~29% since first reported in 1879—with ~7-fold faster rates of decline since 1990 (ref. 72)—due to a combination of natural causes, coastal anthropogenic pressure and climate change73.

Producing accurate estimates of the global extent of BC ecosystems is therefore a prerequisite to assess their contribution in the global carbon cycle. In addition, given the fast rate of decline reported for many BC ecosystems, regular revision of these estimates is needed to track any changes in their global extent and importance. Extensive mapping, with particular focus on understudied areas that may support critical BC ecosystems, that combines acoustic (i.e., side scan sonar and multi-beam eco-sounder) and optical (i.e., aerial photography and satellite images) remote sensing techniques with ground truthing (by scuba diving or video images) should be undertaken to map and monitor their extent and relative change over time74.

Q5. How do organic and inorganic carbon cycles affect net CO 2flux?

Even though BC ecosystems are significant Corg reservoirs, depending on Corg and Cinorg dynamics they could also be net emitters of CO2 to the atmosphere through air-water CO2 gas exchange75. For instance, in submerged BC ecosystems (i.e., seagrasses), Corg storage is not directly linked with the removal of atmospheric CO2 because the water column separates the atmosphere from benthic systems. BC science gaps exist in complex inorganic and organic biogeochemical processes occurring within the water column and determining CO2 sequestration functioning.

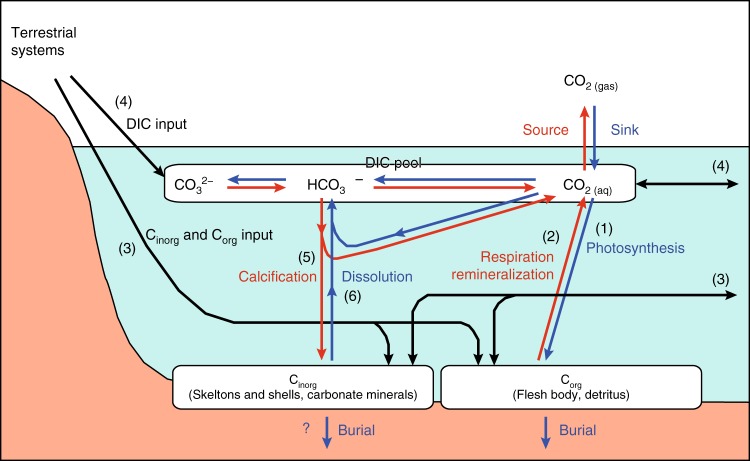

Photosynthesis lowers the CO2 concentration in surface water as dissolved inorganic C (DIC) is incorporated into Corg ((1) in Fig. 1), and respiration and remineralization increases the CO2 concentration ((2) in Fig. 1). Net autotrophic ecosystems would lower surface water CO2 concentration and be a direct sink for atmospheric CO276,77. Lowering of surface water CO2 concentration is facilitated if allochthonous Corg ((3) in Fig. 1) and DIC inputs ((4) in Fig. 1) are low. Reactions of the inorganic C (Cinorg) cycle can also change the CO2 concentration in surface water and therefore influence net exchange of CO2 with the atmosphere4,5,78. Formation of calcium carbonate minerals (calcification) results in an increase of CO2 in the water column ((5) in Fig. 1) while dissolution of carbonate minerals decreases CO2 ((6) in Fig. 1). These processes may critically affect air–water CO2 gas exchange. Although recent studies related to the role of BC in climate change mitigation are beginning to address the abundance and burial rate of Cinorg in soils4,5,54,78–80, studies investigating the full suite of key processes for air–water CO2 fluxes, such as carbonate chemistry and Corg dynamics in shallow coastal waters and sediments, are still scarce (but see76,77,81,82). In particular, relevance of carbonate chemistry to the overall spatio-temporal dynamics of Corg and Cinorg pools and fluxes (e.g., origin, fate, abundance, rate, interactions) and air–water CO2 fluxes is largely uncertain for BC ecosystems4.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual diagram showing the biogeochemistry of carbon associated with air-water CO2 exchanges. Blue lines indicate the processes that enhance the uptake of atmospheric CO2, and red lines indicate those that enhance the emission of CO2 into the atmosphere. The CO2 concentration in surface water is primarily responsible for determining the direction of the flux. The concentration of surface water CO2 is determined by carbonate equilibrium in dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and affected by net ecosystem production (the balance of photosynthesis, respiration, and remineralization), which directly regulate DIC (1 and 2), allochthonous particulate and dissolved organic carbon (Corg), particulate inorganic carbon (Cinorg), and DIC inputs from terrestrial systems and coastal oceans (3 and 4), net ecosystem Cinorg production (the balance of calcification and dissolution), directly regulating both DIC and total alkalinity (TA) (5, 6), and temperature (solubility of CO2). Calcification produces CO2 with a ratio (released CO2/precipitated Cinorg) of approximately 0.6 in normal seawater54

Therefore, in addition to Corg related processes occurring in sediments and vegetation, future BC science should also quantify other key processes, such as air-water CO2 fluxes and Corg and Cinorg dynamics in water, to fully understand the role of BC ecosystems in climate change mitigation83.

Q6. How can organic matter sources be estimated in BC sediments?

Coastal ecosystems, mangroves, seagrasses and tidal marshes, occupy the land-sea interface and are subject to convergent inputs of organic matter from terrestrial and oceanic sources as well as transfers to and from nearby ecosystems84. However, the most basic requirement of quantifying organic matter inputs, and differentiating between allochthonous and autochthonous sources of Corg, remains a challenge. This limitation has particular relevance because of interest in financing the restoration of coastal ecosystems through the sale of BC offset-credits85. Policy frameworks such as the Verified Carbon Standard Methodology VM0033 (ref. 86) stipulate that offset-credits are not allocated under the framework for allochthonous Corg because of the risk of duplicating C sequestration gains that may have been accounted for in adjacent ecosystems. New methods are emerging that have greater potential to quantify the contribution of different primary producers to sedimentary organic carbon in marine ecosystems87.

Natural abundance of stable isotopes, most commonly 13C, 15N and 34S, have been used to trace and quantify allochthonous and autochthonous Corg sources and their relative contributions to carbon burial. The costs are low, the methodology for sample preparation and analysis is relatively easy and the validity of the technique has been widely, and generally successfully tested88. However, the diversity of organic matter inputs can result in complex mixtures of Corg that are not well resolved based on the isotopic separation of the sources. Isotopic values of different species may be similar, or may vary within the same species with microhabitats, seasons, growth cycle or tissue type89,90.

The use of bulk stable isotopes must be improved by additionally analysing individual compounds with a specific taxonomic origin. Biomarkers such as lignin, lipids, alkanes and amino acids, have proven useful for separating multiple-source inputs in coastal sediments88,91. Leading-edge studies, using compound-specific stable isotopes, employ both natural and radiocarbon analyses, providing the added dimension of age to taxonomic specificity92,93. Oxygen and hydrogen stable isotopes could also be used to improve resolving power, but up to now they have been used mainly in foodweb studies and their utility in determining sedimentary sources in coastal systems still needs to be validated87. Studies using both bulk and compound-specific isotopes must consider how decomposition may alter species-specific signatures89,90,94 Other, alternative fingerprinting techniques are emerging. The deliberate stable isotope labelling of organic matter and tracing its fate is a powerful approach that overcomes some of the limitations of natural abundance studies (e.g., source overlap), but has only looked at short-term Corg burial to-date95. The use of environmental DNA (eDNA) has been used to describe community composition in marine systems, but the potential to quantify the taxonomic proportions of plant sources in sediments has rarely been tested87,96.

Overall, projects using 13C and 15N stable isotopes will likely continue to dominate the investigation of organic matter sources, especially in simple two end member systems. While there is a growing suite of organic matter tracers, the ability to distinguish between specific blue carbon sources such as marsh vegetation and seagrass still remains a challenge. Sample size requirement, analytical time and cost implications, will be crucial in the selection of the most appropriate tracers for the characterisation and quantification of the molecular complexity in blue carbon sediments. In general, applications of most compound specific tracers have focused on environments other than those supporting blue carbon ecosystems88,93,97, and more work is needed to apply the same research tools to these systems. We recommend, wherever possible, that complementary methods such as compound-specific isotopes and eDNA that take advantage of methodological advances in distinguishing species contributions, be used in conjunction with bulk isotopes.

Q7. What factors influence BC burial rates?

BC ecosystems have an order of magnitude greater C burial rates than terrestrial ecosystems3. This high BC burial rate is a product of multiple processes that affect: the mass of C produced and its availability for burial; its sedimentation; and its subsequent preservation. A host of interacting biological, biogeochemical and physical factors, as well as natural and anthropogenic disturbance (see Q2), affect these processes. With respect to biological factors, it remains unclear how primary producer diversity and traits (e.g., biochemical composition, productivity, size and biomass allocation) influence BC98,99. However, it is likely that the suite of macrophytes present in BC ecosystems is critical to the mass of C available to be captured and preserved (as suggested for tidal marshes100). Equally, it is uncertain how fauna influence the production, accumulation or preservation of Corg via top-down processes such as herbivory38,101–103. Similarly, predators can regulate biomass, persistence and recovery of seagrasses, marshes and mangroves by triggering trophic cascades38. In addition, the functional diversity and activity of the microbial decomposer community, and how they vary with depth and over time, is only just beginning to be examined104 and will need to be linked to BC burial rates. Most likely this microbial community will be more important in defining the fate of Corg entering BC soils than its production and sedimentation.

The general effects of hydrodynamics on carbon sequestration in BC ecosystems are understood, yet there is much we still do not understand which could explain the variability in sequestration we see across BC ecosystems. We know that hydrodynamics, mediated by biological properties of BC ecosystems (e.g., canopy size and structure), affect particle trapping105–107 and, presumably, Corg sedimentation rates. For example, increasing density of mangrove stands positively affects affect wave attenuation, enhancing the accumulation of fine grained material108, which promotes Corg accumulation (silts and clays retain more Corg than sands109,110. However, significant variation in soil Corg has been observed within seagrass meadow111, pointing to complex canopy-hydrodynamic interactions which we do not understand but which could affect our ability to develop robust estimates of meadow-scale BC burial. For example, a study of restored seagrass meadow found strong positive correlations between Corg stocks and edge proximity leading to gradients in carbon stocks at scales of >1 km112. Elsewhere, flexible canopies have been shown to interact with wave dynamics, increasing turbulence near the sediment surface113. This could explain the loss of fine sediments, and presumably Corg, in low shoot density meadows compared to high density meadows114, with implications for carbon sequestration over time following restoration of BC ecosystems and the development of canopy density. Because these types of hydrodynamic interaction can affect the spatial and temporal patterns in carbon accumulation they need to be better understood in order to design stock and accumulation assessments and to predict the temporal development of stocks following management actions.

The basic biogeochemical controls on Corg accumulation within soils are understood (e.g., biochemical nature of the Corg inputs which vary among primary producers115–117 and the chemistry of their decomposition products)110, but it remains unclear what controls the stability of stored Corg in BC soils and whether these factors vary across ecosystems or under different environmental conditions (incl. disturbance). With the exception of one recent paper43, we know little about the Corg -mineral associations in BC ecosystems, how these affect the recalcitrance of soil Corg or whether specific forms are protected more by this mechanism than others, though this is clearly the case in other ecosystems118–120. Undoubtedly the anaerobic character of BC soils places a significant control on in situ rates of Corg decomposition and remineralisation. However, the time organic materials are exposed to oxygen before entering the anaerobic zone of BC soils will impact the quantity and nature of Corg as will the redox potential reached within the soil. The amount of time organic matter is exposed to oxygen explains the observation that Corg concentrations in tidal marshes globally are higher on coastlines where relative sea level rise has been rapid compared to those where sea level has been relatively stable18. Moreover, exposure of BC to oxygen has been recently shown trigger microbial attack, even ancient (5000-year-old) and chemically recalcitrant BC43. Enhancing our understanding of oxygen exposure times and critical redox potentials will help explain variations in Corg accumulation rates and preservation within different BC ecosystems.

From the above, there is increasing evidence that we do not understand the complex interactions among influencing environmental factors well enough to predict likely Corg stocks in soils, including temperature, hydrodynamic, geomorphic and hydrologic factors that can affect biogeochemical processes or mediate biological processes, and this leads to apparent contradictions. For example, the influence of nutrient availability on Corg stocks is unclear with one study reporting an increase in soil Corg stocks along a gradient of increasing phosphate availability121, another reporting no effect122, and yet others121,123 finding that increasing nutrient availability led to lower soil Corg. Some empirical studies have examined interactive effects or evoked them to explain difference in Corg stock101,124,125. However, these studies are rare and limited by the complexity or the interactions being examined. We conclude that gaining insights into these interactive effects is more likely to be advanced through modelling approaches.

Q8. What is the net flux of greenhouse gases between Blue Carbon ecosystems and the atmosphere?

BC ecosystems are generally substantial sources or sinks of greenhouse gases (GHGs) (CO2, CH4, N2O), though we cannot construct accurate global BC budgets due to uncertainties in net fluxes. The C budget is best constrained for mangroves, with mangroves globally taking up 700 Tg C yr−1 through Gross Primary Production, and respiring 525 Tg C yr−1 (75%) back to the atmosphere as CO2126. However, large uncertainty exists in budgets due to poorly constrained mineralization pathways linked to CO2 efflux119.

We lack robust global C budgets for other BC ecosystems due to insufficient empirical evidence127. For example, while we have estimated global soil Corg stocks128 and accumulation rates for seagrasses, this is insufficient to create a budget129 because we lack representative data on community metabolism and GHG fluxes, particularly for CH4 and N2O emissions. Thus, we need to better quantify sink/source balances, e.g., the net balance between primary production vs. emissions from ecosystem degradation and pelagic, benthic, forest floor and canopy respiration126. We also need to understand how source/sink dynamics change budgets over time and how environmental parameters affect GHG fluxes129,130, allowing us to estimate thresholds that flip BC ecosystems from GHG sinks to sources.

Budgets generally focus on CO2 fluxes, though we must better understand fluxes of other GHGs such as CH4 and N2O, and their contribution to the global BC budget131. Global estimates show that CH4 emissions can offset C burial in mangroves by 20% because CH4 has a higher global warming potential than CO2 on a per molecule basis132. CH4 emissions may also offset C burial in seagrasses, though these estimates have not been made. In contrast, some mangroves are N2O sinks133 which would enhance the value of the C burial as a means to mitigate climate change. Overall, CH4 and N2O biogeochemistry is understudied in BC ecosystems.

Finally, we must understand how GHG fluxes change as BC ecosystems replace each other, such as when mangroves expand onto marshes at their latitudinal limits134, or are planted on seagrass meadows in Southeast Asia. We also need to understand how emissions may change with loss of BC ecosystems. For example, it has been coarsely estimated that a 50% loss of seagrass would result in a global reduction in N2O emissions of 0.012 Tg N2O-N yr−1 and a 50% loss of mangroves would result in a global reduction in emissions of 0.017 Tg N2O-N yr−1 (ref. 130).

Q9. How can we reduce uncertainties in the valuations of Blue Carbon?

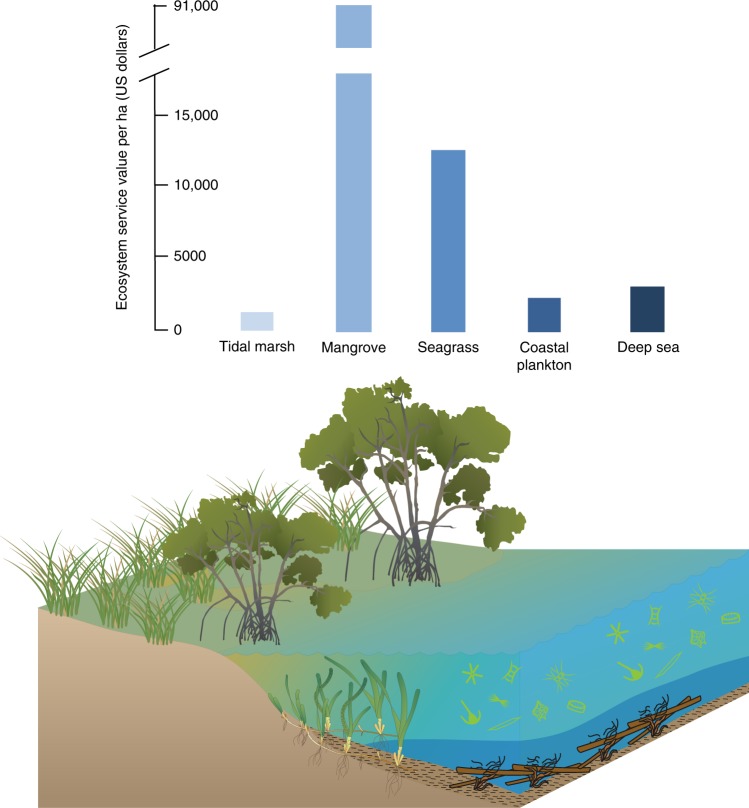

Studies into BC increasingly include a valuation aspect, focussed on coastal sites135 but more recently also including offshore sites136, showing a range of values for different ecosystems as depicted in Fig. 2. Differences in values are driven by differences in BC sequestration and storage capacity and/or potential avoided emissions through conservation and restoration of ecosystems. There is also variation in BC values due to uncertainties in the calculation of C sequestration and permanence of C storage, as is required for valuation. The wide range of C valuation methods, including social costs of C111, marginal abatement costs112, and C market prices, also enhances the uncertainty and variation in valuation estimates.

Fig. 2.

Estimates of the economic value of blue carbon ecosystems per hectare. Data from ref. 1 and references therein. Symbols and images are courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science (ian.umces.edu/symbols/)

Valuation of BC enables its inclusion in policy and management narratives113, facilitating the comparison of future socio-economic scenarios, including mitigation and adaptation interventions137, and raises conservation interests as an approach to mitigate climate change and offset CO2 emissions2. For example, BC budgets can be incorporated into national greenhouse gas inventories138. Alternatively, demonstrable gains in C sequestration and/or avoided emissions through conservation and restoration activities can be credited within voluntary C markets or through the Clean Development Mechanism of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)86. Voluntary market methodologies for BC ecosystems have been released within the American Carbon Registry139 and within the Verified Carbon Standard86, while some countries are developing BC-focussed climate change mitigation schemes that provide economic incentives. However, on the international scale, BC ecosystems have previously not been consistently incorporated into frameworks for climate change mitigation that offer economic reward for the conservation of C sinks, such as the REDD + program140, possibly as there was insufficient information for its inclusion. Avoiding degradation of mangroves, tidal marshes and seagrasses could globally offer up to 1.02 Pg CO2-e yr−1 in avoided emissions37. Developing countries with BC resources have the opportunity to use BC for the NDC, for example Indonesia, where BC contribution to reduce emissions could be as much as 0.2 Pg CO2-e yr−1 or 30% of national land-based emission while mangrove deforestation only contributes to 6% of national deforestation141.

To reduce uncertainty in BC values and encourage use of values in future policy and management, we recommend improved interdisciplinary research, combining ecological and economic disciplines to develop standardised approaches to improve confidence in the valuation of BC. Ideally this should be undertaken alongside studies which recognise the additional values of conserving BC ecosystems, for example the benefits generated from fisheries enhancement, nutrient cycling, support to coastal communities and their livelihoods2 and coastal protection, which is considered a cost-effective method compared to hard engineering solutions142.

Q10. What management actions best maintain and promote Blue Carbon sequestration?

Research over the past decade has improved estimates of C dynamics at a range of spatial scales. This has enabled modelling of potential emissions from the conversion of seagrass, mangrove and tidal marsh to other uses41, and estimates of rates of and hotspots for CO2 emissions resulting from ecosystem loss. The development of policy, implementation of management actions and the demonstration of BC benefits (including payments), however, are still in their infancy.

There are three broad management approaches to enhance C mitigation by BC ecosystems: preservation, restoration and creation. Preserving ecosystem extent and quality—for example, through legislative protection and/or supporting alternative livelihoods—has the two-fold benefit of avoiding the remineralisation of historically sequestered C, while also protecting future sequestration capacity. Preservation may include direct or indirect approaches to maintain or enhance biogeochemical processes, such as sedimentation and water supply46. Restoration pertains to a range of activities seeking to improve biophysical and geochemical processes—and therefore sequestration capacity—in BC ecosystems. Examples include passive and/or active reforestation of logged and degraded mangrove forests143; earthwork interventions to return aquaculture ponds to mangrove ecosystems141; and the restoration of hydrology to drained coastal floodplains144. Managed realignment is a particular option for creating or restoring tidal marshes as part of a strategy to achieve sustainable coastal flood defence together with the provision of other services, including C benefits145; other similar options include: regulated tidal exchange131 and beneficial use of dredged material146. Although restoration may re-establish C sequestration processes, it is important to note that it may not prevent large amounts of fossil C being lost following future disturbance or intervention. ‘No net loss’ policies have been now developed and applied to wetland ecosystems in many countries (e.g., USA and EU). These generally imply the creation of BC ecosystems to replace those lost through development. Such approaches should be treated with caution, however, since there is confusion about terminology141, lack of enforcement and limited capacity to recreate the qualities of pristine sites.

Tools for the accounting and crediting of C payments now exist for coastal wetland conservation, restoration and creation under the voluntary C market86,147. Several small-scale projects (e.g., Mikoko Pamoja in Kenya) are now using these frameworks to generate C credits with others projects in development148. Few jurisdictions have adopted their own mechanisms for the accounting and/or trading of BC, though some have undertaken preliminary research to identify BC policy opportunities149.

Technical, financial and policy barriers remain before local initiatives can be scaled-up to make large impacts—such as through national REDD + initiatives. Significant barriers include: biases in the geographic coverage of data; approaches for robust, site-specific assessment and prediction of some C pools (e.g., below-ground C and atmospheric emissions); high transaction costs; and ensuring that equity and justice are achieved. In addition, most demonstrated efforts are recent actions with little quantification of C mitigation benefits (or societal outcomes) beyond the scale of a few years.

Despite such barriers, we now have the fundamental knowledge to justify the inclusion of BC protection, restoration and creation in C mitigation mechanisms. While there remain knowledge gaps—both in science, policy and governance—these will partly be addressed through the effective demonstration, monitoring and reporting of existing and new BC projects.

Toward a research agenda on the role of vegetated coastal ecosystems on climate change mitigation and adaptation

The questions above are not short of challenges and therefore, provide ample scope for decisive experiments to be designed and conducted, current hypotheses to be rejected or consolidated and new ideas and concepts to unfold. Emerging questions that are not yet supported by robust observations and experiments, include, for example: the estimation of allochthonous C (organic and inorganic) contributions to BC, which remains challenging due to availability of markers able to quantitatively discriminate among the different carbon sources; and the net balance of GHG emissions, which remains challenging as it requires concurrent measurements across relevant time and spatial scales of all major GHGs (CO2, CH4, NO2), for which not a single estimate is available to-date. The core questions that capture much of current research efforts in BC science include the role of climate change on C accumulation, efforts to improve the precision of global estimates of the extent of BC ecosystems, factors that influence sequestration in BC ecosystems, with the corresponding value of BC, and the management actions that are effective in enhancing this value. The preceding text provides a summary of current research efforts and future opportunities in addressing these key questions.

Three questions are long-standing, controversial, and need resolution in order to properly constrain the BC paradigm. The first is the effect of disturbance on GHG emissions from BC ecosystems, where the initial assumption, that the top meter of the soil C stock is likely to be emitted as GHG following disturbance37,128, continues to be carried across papers without being challenged or verified. The second is whether macroalgae-C can be considered BC. The term BC refers to C sequestered in the oceans1, and the focus on seagrass, mangroves and tidal marshes is justified by the intensity of local C sequestration these ecosystems support. If macroalgae provide intense C sequestration, whether in the ecosystem or beyond, they need to be dealt with in this context. And the third controversy is whether carbonate accumulation in BC ecosystems render them potential sinks of CO2 following disturbance. It is clear that there are far too many key uncertainties4 to resolve this at the conceptual level, since empirical evidence to provide a critical test is as yet lacking. We propose that a research program including key observational and experimental tests designed to resolve the mass balance of carbonate (e.g., balance between allochthonous and autochthonous production and dissolution)—and then the coupling between BC ecosystems and the atmosphere—is needed. In the case of all three controversies, we believe that the positive approach to address these questions, is to pause the current discussion, which are largely rooted in the lack of solid, direct empirical evidence, and recognize that further science is required before any conclusion can be reached.

In summary, the overview of questions provided above portrays BC science as a vibrant field that is still far away from reaching maturity. Apparent controversies are a consequence of this lack of maturity and need to be resolved through high quality, scalable and reproducible observations and experiments. We believe the questions above inspire a multifarious research agenda that will require continued broadening the community of practice of BC science to engage scientists from different disciplines working within a wide range of ecosystems and nations.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

P.I.M. and C.E.L. were supported by an Australian Research Council Linkage Project (LP160100242). C.M.D. was supported by baseline funding from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology. T.K. and K.W. were supported by JSPS KAKENHI (18H04156) and the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (S-14) of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. B.D.E. was supported by Australian Research Council grants DP160100248 and LP150100519. D.A.S. was supported by the UK Natural Environment Research Council (NE/K008439/1), and D.K.J. was supported by the CARMA project (8021-00222B), funded by the Independent Research Fund Denmark. Funding was provided to P.M. by the Generalitat de Catalunya (MERS, 2017SGR 1588) and an Australian Research Council LIEF Project (LE170100219). This work is contributing to the ICTA ‘Unit of Excellence’ (MinECo, MDM2015-0552). O.S. was supported by an ARC DECRA (DE170101524). N.M. was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (MedShift project). N.B. was supported by the UK Research Councils under Natural Environment Research Council award NE/N013573/1. J.W.F. was supported by the US National Science Foundation through the Florida Coastal Everglades Long-Term Ecological Research program under Grant No. DEB-1237517. R.S. had the support of FCT, project FCT UID/MAR/00350/2018. I.E.H. was supported by Ramon y Cajal Fellowship RYC2014-14970, co-funded by the Conselleria d’Innovació, Recerca i Turisme of the Balearic Government and the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness. The University of Dundee is a registered Scottish charity, no. 015096. J.P.M. was supported by the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology Program (DEB-0950080, DEB-1457100, DEB-1557009).

Author contributions

P.I.M., A.A., J.A.R. and C.M.D. designed the study. P.I.M., A.A., J.A.R., N.B., R.M.C., D.A.F., J.J.K., H.K., T.K., P.S.L., C.E.L., D.A.S., E.T.A., T.B.A., J.B., T.S.B., G.L.C., B.D.E., J.W.F., J.M.H.-S., M.H., I.E.H., D.K.-J., D.L., T.L., N.M., P.M., K.J.M., P.J.M., D.M., B.D.R., R.S., O.S., B.R.S., K.W. and C.M.D. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/8/2019

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-11693-w.

References

- 1.Nellemann C., et al. (eds) Blue Carbon. A Rapid Response Assessment. United Nations Environment Programme (GRID-Arendal, 2009). This report was the first to use the term ‘blue carbon’

- 2.Duarte CM, Losada IJ, Hendriks IE, Mazarrasa I, Marba N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Change. 2013;3:961–968. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLeod E, et al. A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2011;9:552–560. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macreadie Peter I, Serrano O, Maher Damien T, Duarte Carlos M, Beardall J. Addressing calcium carbonate cycling in blue carbon accounting. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 2017;2:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard J, et al. Clarifying the role of coastal and marine systems in climate mitigation. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017;15:42–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause-Jensen Dorte, Duarte Carlos M. Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration. Nature Geoscience. 2016;9(10):737–742. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith SV. Marine macrophytes as a global carbon sink. Science. 1981;211:838–840. doi: 10.1126/science.211.4484.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte CM, Middelburg JJ, Caraco N. Major role of marine vegetation on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences. 2005;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy H., et al. in Supplement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories: Wetlands (eds Hiraishi, T., et al.) (IPCC, 2014).

- 10.Arias-Ortiz A, et al. A marine heatwave drives massive losses from the world’s largest seagrass carbon stocks. Nat. Clim. Change. 2018;8:338. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marbà N, et al. Impact of seagrass loss and subsequent revegetation on carbon sequestration and stocks. J. Ecol. 2015;103:296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macreadie PI, et al. Losses and recovery of organic carbon from a seagrass ecosystem following disturbance. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2015;282:1–6. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atwood TB, et al. Global patterns in mangrove soil carbon stocks and losses. Nat. Clim. Change. 2017;7:523. [Google Scholar]

- 14.IPCC. Climate Change. 2007. Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva, Switzerland, 2007).

- 15.Cabanes C, Cazenave A, Le Provost C. Sea level rise during past 40 years determined from satellite and in situ observations. Science. 2001;294:840–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1063556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen J, et al. Global temperature change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14288–14293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606291103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knutson TR, et al. Tropical cyclones andclimate change. Nat. Geosci. 2010;3:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers K, et al. Wetland carbon storage controlled by millennial-scale variation in relative sea-level rise. Nature. 2019;567:91–95. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0951-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirwan ML, Megonigal JP. Tidal wetland stability in the face of human impacts and sea-level rise. Nature. 2013;504:53–60. doi: 10.1038/nature12856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovelock CE, et al. The vulnerability of Indo-Pacific mangrove forests to sea-level rise. Nature. 2015;526:559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature15538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodroffe C.D., Rogers K., McKee K.L., Lovelock C.E., Mendelssohn I.A., Saintilan N. Mangrove Sedimentation and Response to Relative Sea-Level Rise. Annual Review of Marine Science. 2016;8(1):243–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-034025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuerch M, et al. Future response of global coastal wetlands to sea-level rise. Nature. 2018;561:231–234. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelleway JJ, et al. Seventy years of continuous encroachment substantially increases ‘blue carbon’ capacity as mangroves replace intertidal salt marshes. Glob. Change Biol. 2016;22:1097–1109. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albert Simon, Saunders Megan I, Roelfsema Chris M, Leon Javier X, Johnstone Elizabeth, Mackenzie Jock R, Hoegh-Guldberg Ove, Grinham Alistair R, Phinn Stuart R, Duke Norman C, Mumby Peter J, Kovacs Eva, Woodroffe Colin D. Winners and losers as mangrove, coral and seagrass ecosystems respond to sea-level rise in Solomon Islands. Environmental Research Letters. 2017;12(9):094009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SY, Hamilton S, Barbier EB, Primavera J, Lewis RR. Better restoration policies are needed to conserve mangrove ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:870–872. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0861-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellison JC. Mangrove retreat with rising sea-level, Bermuda. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 1993;37:75–87. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wernberg T, et al. An extreme climatic event alters marine ecosystem structure in a global biodiversity hotspot. Nat. Clim. Change. 2013;3:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reef R, et al. The effects of elevated CO2 and eutrophication on surface elevation gain in a European salt marsh. Glob. Change Biol. 2017;23:881–890. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asbridge E, Lucas R, Ticehurst C, Bunting P. Mangrove response to environmental change in Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria. Ecol. Evol. 2016;6:3523–3539. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syvitski JPM, et al. Sinking deltas due to human activities. Nat. Geosci. 2009;2:681–686. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spencer T, et al. Global coastal wetland change under sea-level rise and related stresses: the DIVA Wetland Change Model. Glob. Planet. Change. 2016;139:15–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balke T, Friess DA. Geomorphic knowledge for mangrove restoration: a pan-tropical categorization. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2016;41:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonardi N, Ganju NK, Fagherazzi S. A linear relationship between wave power and erosion determines salt-marsh resilience to violent storms and hurricanes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:64–68. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510095112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders MI, et al. Interdependency of tropical marine ecosystems in response to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change. 2014;4:724–729. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saderne V, et al. Accumulation of carbonates contributes to coastal vegetated ecosystems keeping pace with sea level rise in an Arid Region (Arabian Peninsula) J. Geophys. Res. 2018;123:1498–1510. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saunders MI, et al. Coastal retreat and improved water quality mitigate losses of seagrass from sea level rise. Glob. Change Biol. 2013;19:2569–2583. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pendleton L, et al. Estimating global “blue carbon” emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43542–e43542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atwood TB, et al. Predators help protect carbon stocks in blue carbon ecosystems. Nat. Clim. Change. 2015;5:1038–1045. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bouma TJ, et al. Identifying knowledge gaps hampering application of intertidal habitats in coastal protection: opportunities & steps to take. Coast. Eng. 2014;87:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lovelock CE, et al. Assessing the risk of carbon dioxide emissions from blue carbon ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017;15:257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovelock, C. E., Fourqurean, J. W. & Morris, J. T. Modeled CO2 emissions from coastal wetland transitions to other land uses: tidal marshes, mangrove forests, and seagrass beds. Front. Mar. Sci.4, 1–11 (2017).

- 42.Macreadie PI, Hughes AR, Kimbro DL. Loss of ‘blue carbon’ from coastal salt marshes following habitat disturbance. PLoS One. 2013;8:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macreadie, P. I., et al. Vulnerability of seagrass blue carbon to microbial attack following exposure to warming and oxygen. 686, 264–275 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Silliman BR, et al. Degradation and resilience in Louisiana salt marshes after the BP-deepwater horizon oil spill. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:11234–11239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204922109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sidik F, Lovelock CE. CO2 efflux from shrimp ponds in Indonesia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macreadie PI, et al. Can we manage coastal ecosystems to sequester more blue carbon? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017;15:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coverdale TC, et al. Indirect human impacts reverse centuries of carbon sequestration and salt marsh accretion. PLoS One. 2014;9:e9396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Duarte CM. Reviews and syntheses: hidden forests, the role of vegetated coastal habitats in the ocean carbon budget. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raven JA. The possible roles of algae in restricting the increase in atmospheric CO2 and global temperature. Eur. J. Phycol. 2017;52:506–522. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Trevathan-Tackett SM, et al. Comparison of marine macrophytes for their contributions to blue carbon sequestration. Ecology. 2015;96:3043–3057. doi: 10.1890/15-0149.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hill R, et al. Can macroalgae contribute to blue carbon? An Australian perspective. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015;60:1689–1706. [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Heijden LH, Kamenos NA. Reviews and syntheses: calculating the global contribution of coralline algae to total carbon burial. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:6429–6441. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith, S. V. Parsing the Oceanic Calcium Carbonate Cycle: a Net Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Source, or a Sink? (Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) L&O e-Books, 2013).

- 54.Saderne V, et al. Role of carbonate burial in Blue Carbon budgets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1106. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Along, D. M. The Energetics of Mangrove Forests (Springer Science and Business Media BV, 2009).

- 56.Giri C, et al. Status and distribution of mangrove forests of the world using earth observation satellite data. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011;20:154–159. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hamilton SE, Casey D. Creation of a high spatio-temporal resolution global database of continuous mangrove forest cover for the 21st century (CGMFC-21) Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2016;25:729–738. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valiela I, Bowen JL, York JK. Mangrove forests: one of the world’s threatened major tropical environments. Bioscience. 2001;51:807–815. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adame MF, et al. Carbon stocks of tropical coastal wetlands within the Karstic landscape of the Mexican Caribbean. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56569. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lugo AE. Old-growth mangrove forests in the United States. Conserv Biol. 1997;11:11–20. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Adam P. Saltmarshes in a time of change. Environ. Conserv. 2002;29:39–61. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woodwell, G.M., Rich, P.H., Mall, C.S.A. Carbon in the Biosphere. In: Woodwell, G.M., Pecan, E.V. (eds.) Proceedings of the 24th Brookhaven Symposium in Biology pp. 221–240 (USAEC, Springfield, Virginian, 1973).

- 63.Mcowen Chris, Weatherdon Lauren, Bochove Jan-Willem, Sullivan Emma, Blyth Simon, Zockler Christoph, Stanwell-Smith Damon, Kingston Naomi, Martin Corinne, Spalding Mark, Fletcher Steven. A global map of saltmarshes. Biodiversity Data Journal. 2017;5:e11764. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.5.e11764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chmura GL, Anisfeld SC, Cahoon DR, Lynch JC. Global carbon sequestration in tidal, saline wetland soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles. 2003;17:1111. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Macreadie, P. I., et al. Carbon sequestration by Australian tidal marshes. Sci. Rep.www.nature.com/articles/srep44071 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Lotze HK, et al. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science. 2006;312:1806–1809. doi: 10.1126/science.1128035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duarte CM, Dennison WC, Orth RJW, Carruthers TJB. The charisma of coastal ecosystems: addressing the imbalance. Estuaries Coasts. 2008;31:233–238. [Google Scholar]

- 68.UNEP-WCMC. Global distribution of seagrasses (version 4.0). Fourth update to the data layer used in Green and Short (2003) (UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, 2016).

- 69.Charpy-Roubaud C, Sournia A. The comparative estimation of phytoplanktonic, microphytobenthic and macrophytobenthic primary production in the oceans. Mar. Microb. Food Webs. 1990;4:31–57. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gattuso JP, et al. Light availability in the coastal ocean: impact on the distribution of benthic photosynthetic organisms and their contribution to primary production. Biogeosciences. 2006;3:489–513. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Short FT, et al. Extinction risk assessment of the world’s seagrass species. Biol. Conserv. 2011;144:1961–1971. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Waycott M, et al. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12377–12381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905620106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orth RJ, et al. A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. Bioscience. 2006;56:987–996. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pham Tien Dat, Xia Junshi, Ha Nam Thang, Bui Dieu Tien, Le Nga Nhu, Tekeuchi Wataru. A Review of Remote Sensing Approaches for Monitoring Blue Carbon Ecosystems: Mangroves, Seagrassesand Salt Marshes during 2010–2018. Sensors. 2019;19(8):1933. doi: 10.3390/s19081933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Regnier P, et al. Anthropogenic perturbation of the carbon fluxes from land to ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2013;6:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maher, D. T. & Eyre, B. D. Carbon budgets for three autotrophic Australian estuaries: implications for global estimates of the coastal air-water CO2 flux. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles26, GB1032 (2012).

- 77.Tokoro T, et al. Net uptake of atmospheric CO2 by coastal submerged aquatic vegetation. Glob. Change Biol. 2014;20:1873–1884. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Howard Jason L, Creed Joel C, Aguiar Mariana VP, Fourqurean James W. CO2 released by carbonate sediment production in some coastal areas may offset the benefits of seagrass “Blue Carbon” storage. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017;63:160–172. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mazarrasa I, et al. Seagrass meadows as a globally significant carbonate reservoir. Biogeosciences. 2015;12:4993–5003. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fodrie F. Joel, Rodriguez Antonio B., Gittman Rachel K., Grabowski Jonathan H., Lindquist Niels. L., Peterson Charles H., Piehler Michael F., Ridge Justin T. Oyster reefs as carbon sources and sinks. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2017;284(1859):20170891. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.0891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Watanabe K, Kuwae T. How organic carbon derived from multiple sources contributes to carbon sequestration processes in a shallow coastal system? Glob. Change Biol. 2015;21:2612–2623. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bauer JE, et al. The changing carbon cycle of the coastal ocean. Nature. 2013;504:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature12857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kuwae T, et al. Blue carbon in human-dominated estuarine and shallow coastal systems. Ambio. 2016;45:290–301. doi: 10.1007/s13280-015-0725-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hyndes GA, et al. Mechanisms and ecological role of carbon transfer within coastal seascapes. Biol. Rev. 2013;89:232–254. doi: 10.1111/brv.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murray, B., Pendleton, L., Jenkins, W. & Sifleet, S. Green Payments for Blue Carbon: Economic Incentives for Protecting Threatened Coastal Habitats (Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University, Durham, 2011).

- 86.Emmer, I., et al. Methodology for Tidal Wetland and Seagrass Restoration. in Verified Carbon Standard.VM0033 (2015) The first voluntary market methodology for blue carbon ecosystems

- 87.Geraldi NR, et al. Fingerprinting Blue Carbon: rationale and tools to determine the source of organic carbon in marine depositional environments. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019;6:263. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bianchi Thomas S., Schreiner Kathryn M., Smith Richard W., Burdige David J., Woodard Stella, Conley Daniel J. Redox Effects on Organic Matter Storage in Coastal Sediments During the Holocene: A Biomarker/Proxy Perspective. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 2016;44(1):295–319. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kramer MG, Lajtha K, Aufdenkampe AK. Depth trends of soil organic matter C:N and 15N natural abundance controlled by association with minerals. Biogeochemistry. 2017;136:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Canuel, E. A. & Hardison, A. K. Sources, ages, and alteration of organic matter in estuaries. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci.8, 409–434 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 91.Upadhayay HR, et al. Methodological perspectives on the application of compound-specific stable isotope fingerprinting for sediment source apportionment. J. Soils Sediment. 2017;17:1537–1553. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wakeham SG, McNichol AP. Transfer of organic carbon through marine water columns to sediments – insights from stable and radiocarbon isotopes of lipid biomarkers. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:6895–6914. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Canuel EA, Hardison AK. Sources, ages, and alteration of organic matter in estuaries. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2016;8:409–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-034058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Oreska Matthew PJ, Wilkinson Grace M, McGlathery Karen J, Bost M, McKee Brent A. Non‐seagrass carbon contributions to seagrass sediment blue carbon. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018;63:S3–S18. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Oakes JM, Eyre BD. Transformation and fate of microphytobenthos carbon in subtropical, intertidal sediments: potential for long-term carbon retention revealed by 13C-labeling. Biogeosciences. 2014;11:1927–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Reef R, et al. Using eDNA to determine the source of organic carbon in seagrass meadows. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2017;62:1254–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Close HG. Compound-specific isotope geochemistry in the ocean. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2019;11:27–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-121916-063634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Handa IT, et al. Consequences of biodiversity loss for litter decomposition across biomes. Nature. 2014;509:218. doi: 10.1038/nature13247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chapin FS. Effects of plant traits on ecosystem and regional processes: a conceptual framework for predicting the consequences of global change. Ann. Bot. 2003;91:455–463. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcg041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kelleway JJ, Saintilan N, Macreadie PI, Baldock JA, Ralph PJ. Sediment and carbon deposition vary among vegetation assemblages in a coastal salt marsh. Biogeosciences. 2017;14:3763–3779. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thomas CR, Blum LK. Importance of the fiddler crab Uca pugnax to salt marsh soil organic matter accumulation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010;414:167–177. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Johnson RA, Gulick AG, Bolten AB, Bjorndal KA. Blue carbon stores in tropical seagrass meadows maintained under green turtle grazing. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13545. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13142-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.He Q, Silliman BR. Consumer control as a common driver of coastal vegetation worldwide. Ecol. Monogr. 2016;86:278–294. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu SL, et al. Sediment microbes mediate the impact of nutrient loading on blue carbon sequestration by mixed seagrass meadows. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;599:1479–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gacia E, Duarte CM. Sediment retention by a mediterranean Posidonia oceanica meadow: the balance between deposition and resuspension. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 2001;52:505–514. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hansen JCR, Reidenbach MA. Wave and tidally driven flows in eelgrass beds and their effect on sediment suspension. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2012;448:271–287. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wilkie L, O’Hare MT, Davidson I, Dudley B, Paterson DM. Particle trapping and retention by Zostera noltii: a flume and field study. Aquat. Bot. 2012;102:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Horstman EM, Dohmen-Janssen CM, Narra PMF, van den Berg NJF, Siemerink M. Hulscher SJMH. Wave attenuation in mangroves: a quantitative approach to field observations. Coast. Eng. 2014;94:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Keil RG, Hedges JI. Sorption of organic matter to mineral surfaces and the preservation of organic matter in coastal marine sediments. Chem. Geol. 1993;107:385–388. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Burdige DJ. Preservation of organic matter in marine sediments: controls, mechanisms, and an imbalance in sediment organic carbon budgets? Chem. Rev. 2007;107:467–485. doi: 10.1021/cr050347q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ricart AM, et al. Variability of sedimentary organic carbon in patchy seagrass landscapes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015;100:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oreska MPJ, McGlathery KJ, Porter JH. Seagrass blue carbon spatial patterns at the meadow-scale. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Abdolahpour M, Ghisalberti M, McMahon K, Lavery PS. The impact of flexibility on flow, turbulence, and vertical mixing in coastal canopies. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2018;63:2777–2792. [Google Scholar]

- 114.van Katwijk MM, Bos AR, Hermus DCR, Suykerbuyk W. Sediment modification by seagrass beds: muddification and sandification induced by plant cover and environmental conditions. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2010;89:175–181. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Trevathan-Tackett SM, et al. A global assessment of the chemical recalcitrance of seagrass tissues: Implications for long-term carbon sequestration. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:925. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Torbatinejad NM, Annison G, Rutherfurd-Markwick K, Sabine JR. Structural constituents of the seagrass Posidonia australis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:4021–4026. doi: 10.1021/jf063061a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kogel-Knabner I. The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002;34:139–162. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Yeasmin S, Singh B, Johnston CT, Sparks DL. Organic carbon characteristics in density fractions of soils with contrasting mineralogies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2017;218:215–236. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lehmann J, Kleber M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature. 2015;528:60–68. doi: 10.1038/nature16069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baldock JA, Skjemstad JO. Role of the soil matrix and minerals in protecting natural organic materials against biological attack. Org. Geochem. 2000;31:697–710. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Armitage AR, Fourqurean JW. Carbon storage in seagrass soils: long-term nutrient history exceeds the effects of near-term nutrient enrichment. Biogeosciences. 2016;13:313–321. [Google Scholar]