Abstract

The ageing of populations worldwide has implications for workforces in developed countries, and labour shortages have increasingly become a political concern. Governments in developed countries have responded by increasing the retirement age as a strategy for overcoming the fall in labour supply. Using bibliometric techniques, we reviewed 122 articles published between 1990 and 2018 to examine the effectiveness of the strategy in addressing the labour shortages and, in particular, to identify the factors that contribute positively to maintaining worker participation within an ageing workforce at an organizational level. The results identified five organizational factors that support continued participation: health, institutions, human resource management, human capital and technology tools. Employers will increasingly need to develop “age-friendly” workplaces and practices if they are to recruit and retain older workers.

Keywords: Ageing workforce, Labour market, Organization, Bibliometrics

Introduction

The challenges and opportunities experienced during the development of a country are highly connected with demographic trends. Currently, an increase in life expectancy and a fall in fertility rates are expected to influence the social and economic systems of countries. However, the ageing of populations is no longer, solely, an issue of developed countries (Nagarajan et al. 2015), as this shift towards on older demographic is a global trend that is also emergent in lower- and middle-income countries. The unprecedented nature of world population ageing is a “wicked problem”—a notion that perceives the challenge as one that can only be solved via multiple solutions, since the obvious solution may be one that creates more difficulties (Riva et al. 2014). Hence, the issue of global ageing has received much greater attention in recent years among scientific researchers and policymakers.

A decline in fertility rates will result in a smaller working population in future, while a decline in mortality rates will increase the older population (Schlick et al. 2013). Therefore, the current demographic transition means the size of the young working people in the workforce will decrease over time; meanwhile, the proportion of the older population shows a constant rise. An examination of the effect that ageing groups have on human capital and labour market participation is necessary, since a nation’s productivity and quality of life (i.e. daily living standards) are dependent on the overall employment rate as well as the average labour productivity (Beach 2008; Schuring et al. 2013; Siliverstovs et al. 2011). For example, in developed countries such as Australia, it was predicted that between 1998 and 2016, people at age 45 and above would account for 80 per cent of the labour force (Brooks 2003). This demographic shift exemplifies an expected increase in the ratio of workers to retirees in Australia.

The constant growth of the ageing population within workforces has the tendency to decrease the labour supply, which would in turn increase the labour costs and reduce the productivity level (Lisenkova et al. 2012). For example, Albuquerque and Ferreira (2015) found that the presence of population ageing in Portugal is contributing to the change of the Portuguese workforce and their level of production within the regions. In fact, this demographic change is likely to have a profound effect on several other European countries since retiring from the workforce before the statutory retirement age is a common practice (Kroon et al. 2017). Therefore, the rising ageing population and the tendency to retire before the retirement age are likely to contribute to the shortage of labour force in the labour market.

Similar to the majority of the European countries, Canada has also been experiencing an increase in their ageing population. According to Beach (2008), the speed of ageing in Canada is faster than other OECD countries between 2010 and 2030. Moreover, Fougère et al. (2009) indicated that the decline in the working population in Canada has been largely due to an increasing number of retirees and fall in the number of young workers entering the workforce. The baby boomer population that emerged between 1947 and 1966 entered retirement in 2012, at the age of 65, resulting in the presence of larger ageing populations outside the workforce in Canada (Sharpe 2011).

The rising number of retirees has been consistently associated with lower savings, a fall in productivity levels and a rise in government spending (Bloom et al. 2010; Fougère et al. 2009; Sharpe 2011; Walder and Döring 2012). In fact, the augmentation in the old-age dependency ratio (old-age population over the working-age population) may result in a smaller amount of working groups to care for the growing senior population (Lindh 2004; Navaneetham and Dharmalingam 2012; Schuring et al. 2013). Population ageing tends to directly affect budget decisions, as a government’s priority will ultimately shift to spending more on health and social security (Lisenkova et al. 2012). Consequently, the government will feel pressured in redirecting public funds for the social benefits and less focusing on the needs and preferences of young and working population. When the retirement age was set at 65, the retirement saving was considered to be enough to support them; however, as life expectancy continues to increase and the baby boomer generation retires, the established retirement age is no longer feasible, with the pensions crisis and labour shortages being the primary concerns (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer 2006).

The current demographic transition process is likely to both dampen revenue growth and put pressure on government spending that is particularly relevant to the needs of the older population, such as healthcare and public pensions (Nagarajan et al. 2015). To reduce the impacts of a growing older adult population on governmental budgetary planning, postponing the retirement age was proposed as a high-level solution with implications for policy and practice (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Finch 2014). Meanwhile, at the individual level, various factors (e.g. optimal health condition, financial needs, competent performance) were identified as necessary preconditions required for older workers to (re-)engage in the workforce (Sewdas et al. 2017). However, whether or not older people opt to stay in the workforce, supporting ageing workers to remain in the workforce at the organizational level appeared to be the most challenging (Axelrad et al. 2013).

Researchers have claimed that the rise in the retirement age is likely to reduce the productivity level of senior workers (Lisenkova et al. 2012), as their physical and mental health is likely to diminish as they age (Hertel and Zacher 2018; Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald 2003). As a result, once the proportion of older employees exceeds that of younger employees, total productivity is likely to drop (Schlick et al. 2013). However, this is not a universally accepted theory. In contrast to Schlick et al. (2013) and Lisenkova et al. (2012), some authors have argued that a decline in productivity levels is related not to workers’ health and cognitive functions but the surrounding of workplace and their willingness to participate in training and career development activities (Ng and Feldman 2012). This is a crucial issue and suggests that policies to increase workforce participation in older adults should focus on organizational supports, rather than individual-level interventions that are primarily driven by assumptions of declining cognitive and physical capacities as individual age. Bilinska et al. (2016), for example, stressed that in an age-friendly work environment, older workers are less likely to be perceived as being less productive than they might be in a less age-friendly environment.

Some research has demonstrated that workers’ age is generally unrelated to job performance. For example, Ng and Feldman (2008, 2012) suggest that workers’ physical and mental health may begin to decline while they are still in employment, but it may not affect workplace performance. Furthermore, people who live longer are likely to stay healthier and to have higher education levels, which could help to offset the decline of the labour force (Hertel and Zacher 2018). The lifelong learning has shown to help ageing workers to improve their physical and mental health and even to perform well in the labour market (Hertel and Zacher 2018). Hence, in addition to noting the negative consequences of raising the retirement age, literature suggested supportive measures that could bolster productivity in ageing workforces, including: (1) investment in human capital (e.g. on-the-job and technical training) (Hertel and Zacher 2018; Ludwig et al. 2011); (2) health and wellness benefits (e.g. frequent medical checkups and ongoing medical coverage for older workers) (Hertel and Zacher 2018; Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald 2003); and (3) workplace health and safety measures (e.g. task automation and improved workplace ergonomics) (Case et al. 2015; Choi 2009; Fritzsche et al. 2014) and flexible work schedules (e.g. encouraging teleworking and regular rest breaks) (Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser 2011, Wendsche et al. 2016, 2017a, b). For instance, Fritzsche et al. (2014) noted that in Germany, workplace ergonomics and team diversity may play a role in circumventing any productivity risks arising from an ageing workforce in manufacturing industries. Thus, optimal ergonomics could be a key factor in helping older employees remain in the workforce while simultaneously enhancing their productivity levels.

Increasing the retirement age and retaining ageing workers in the labour market has been the way in which many organizations have overcome the issue of labour shortages and a rise in government expenditures. The strategy of raising the retirement age beyond the age of 65 years is unprecedented, and considering the contribution of the peer-reviewed articles on this matter in recent years, it seems timely to take a comprehensive and objective account of this stream of the literature. Therefore, we focus on identifying factors that support ageing workforces to stay engaged in the labour market at an organizational level. Based on the bibliometric methods, this study intends to (1) analyse the emergent topics associated with this literature; (2) identify the relative scientific importance of the main factors that support the participation of the older workers at the organizational level; (3) examine the taxonomy of age in the context of the ageing workforce; (4) analyse and categorize the main methodological approaches that have been used in the literature; and (5) identify the gaps in the scientific literature that require further attention.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: In “Methodology” section, we describe the methodology employed in the bibliometric analysis. “Empirical results” section details the results of the analysis, looking at the general evolution of articles on the ageing workforce (“General evolution of articles on the ageing workforce” section), examining the scientific importance of organizational factors on ageing workforce (“The scientific importance of organizational factors on ageing workforce” section), studying the evolution of the organizational factors of the ageing workforce (“The evolution of the organizational factors of the ageing workforce” section), describing the methodological evolution of research on the ageing workforce (“The methodological evolution of research on the ageing workforce” section) and identifying the scientific age classification of the ageing workforce (“The scientific age classification of the ageing workforce” section). Finally, “Final remarks regarding the ageing workforce” section concludes the article and offers some final remarks regarding the ageing workforce.

Methodology

The topic of “ageing and the ageing labour” is unprecedented. As such, it was important that we select the most appropriate review method to capture, extract and synthesize the existing body of work in an effective way. Bibliometric review appeared to be a more appropriate method of review for our analysis than other systematic narrative review methods (e.g. scoping review, environmental scanning and traditional literature review). Unlike other systematic narrative review methods, bibliometrics is essentially a statistical analysis that quantifies the peer-reviewed articles. In our particular study, it was used to examine the development of articles on ageing workers over time (Fetscherin and Heinrich 2015; Peterson et al. 2016). It is also an effective approach to examining the popularity of a research area, as it allows for analysis of the citation of articles and the focus of research (Fetscherin and Usunier 2012; Peterson et al. 2016). These factors were key in our decision to use bibliometrics in order to examine the current state of research on the ageing workforce.

Published articles were searched and retrieved from SciVerse Scopus (from Elsevier). Three main sources of data that were available for extracting peer-reviewed articles include ISI Web of Science (WOS), Google Scholar (GS) and Scopus (Nagarajan et al. 2015). Among those, Scopus was recognized as the most appropriate database for this study, considering the consistency, adequacy, availability of information and frequent updates on the search results (Adriaanse and Rensleigh 2013; Falagas et al. 2008; Norris and Oppenheim 2007). For this bibliometric survey, the inclusion and exclusion criteria proposed by Fang et al. (2016) were applied to identify the relevance of the articles on the ageing workforce (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Published articles from 1990 to 2018 | Published articles before 1990 |

| Focuses on ageing workforce | Does not focus on ageing workforce |

| Articles that are available through the university library services or are free of charge | Require a fee or are unavailable at the university library |

| Articles that are available in English | Articles that are available in other languages than English |

| Focuses on organizational factors that influence ageing workforce |

To search the database, we used the keywords in the fields “keywords”, “article title” and “abstract”: “ageing workers”, “ageing workers AND technology”, “ageing workers AND productivity” or “ageing population AND employment”. We limited our search to articles written in English; social sciences and the humanities were chosen as the areas of research. Table 2 presents in detail the selection of the keywords used to search the database. Since this research focused on organizational supports for older workers to remain engaged in workforce, variables at the individual level (e.g. health condition, financial status) were not included as part of the search terms.

Table 2.

Relevance of keywords

| Keywords | Relevance | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Ageing workforce | The ageing population within workforces | Albuquerque and Ferreira (2015), Beach (2008) and Fougère et al. (2009) |

| Technology | Technology skills development assists senior workers performance | Case et al. (2015), Choi (2009) and Gonzalez and Morer (2016) |

| Productivity | Ageing population within workforces reduces the productivity level. | Lisenkova et al. (2012) |

| Physical and mental health of senior workers reduces the productivity level. | Boenzi et al. (2015a), Hertel and Zacher (2018) and Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald (2003) | |

| Employment | Heightening the retirement age is likely to increase the employability of senior workers. | Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer (2006), Carmichael and Ercolani 2015 and Finch (2014) |

All the potential peer-reviewed articles were assessed through reviewing their titles, abstracts and, subsequently, the full articles. At the preliminary stage of assessment (screening through articles and abstracts), 92 articles were excluded since their foci were not related to the ageing workforce (including topics such as migration in the workforce, female participation in the workforce and the demographic transition process). The full-text review yielded 122 peer-reviewed articles in the bibliometric analysis.

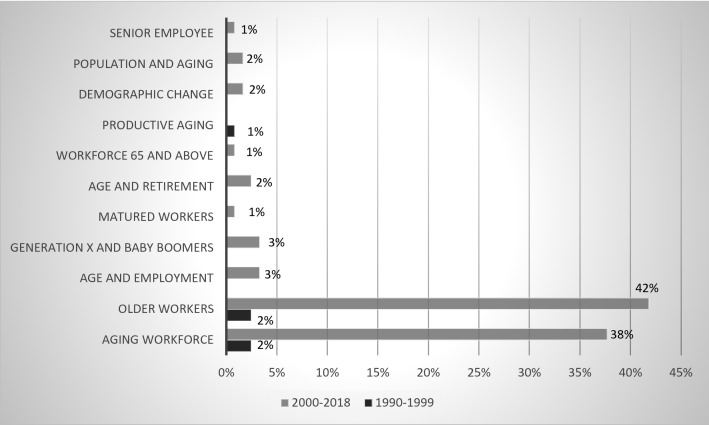

We decided to use the term “ageing workers” as a keyword because mid-career workers (age 40 and above) seemed to become an older worker/ageing worker once they started to plan for retirement. The current demographic transition has increased the age at which workers are reclassified as older workers/ageing workers/senior employees, and therefore topic ageing and work has become the “defining issue of our time” (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer 2006, pg. 1). Since the issue of an increasing ageing population and the associated rise in the participation of that older population (senior, aged 60 and older) in the workforce is unprecedented (Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer 2006), we opted to limit our search terms for this group to “ageing workers”. However, to assist with future reviews in this research, we reviewed the titles and abstracts of the 122 peer-reviewed articles to identify the most frequently used terms to describe older populations in the workforce (see Fig. 1). From our analysis, we have identified “older workers” as the most frequently used term to describe older employees, followed by “ageing workers”.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of terms used to describe ageing population in the workforce.

Source: Authors’ computation based on 122 articles gathered from the Scopus database (Data accessed on November 8, 2017)

The 122 peer-reviewed articles were carefully reviewed, and key information was extracted by the first, second and third authors to ensure reliability. The first author categorized the key information according to the organizational factors that support the participation of the ageing workforce, the types of methodologies considered in analysing ageing workforce and the sample of age examined in the empirical studies to classify the ageing workforce.

For the methodological evolution, articles were classified according to qualitative and quantitative research. Literature that focused on exploratory research (survey, appreciative, scoping review and environmental scanning types) was identified as qualitative research. Meanwhile, literature that focused on empirical analyses was grouped as quantitative research. Under quantitative research, literature that focused on empirical studies was made distinct according to “macro-analysis” and “micro-analysis”. Empirical studies that focused on aggregate data that represented countries were categorized as macro-analysis, while studies that consider a particular group of older workers, firms or industries were classified under micro-analysis.

Empirical results

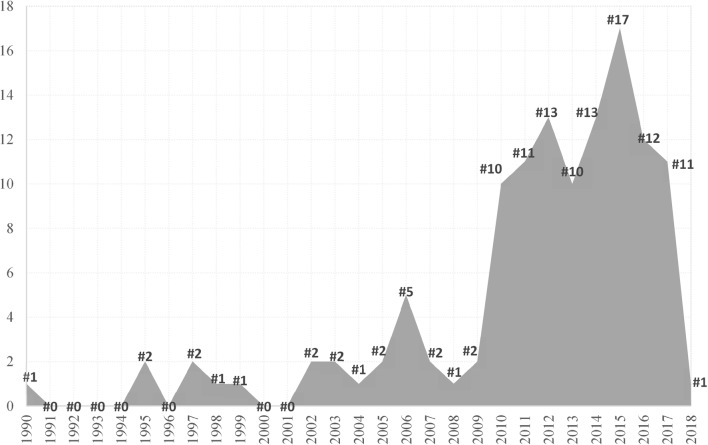

General evolution of articles on the ageing workforce

Our bibliometric analysis generated a number of scientific research works that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria related to the ageing workforce from 1990 to 2009, with only 24 articles published during this period with an average of 1.2 articles per year. However, the study of literature related to the ageing workforce was more visible in later years—2010 onwards (see Fig. 2). Within the next nine years (2010–2018), a total of 98 articles, with an average of 10.9 articles per year, contributed to the ageing workforce literature. An increase in the number of publications on the ageing workforce reflects a rising interest and appetite for research on this topic.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of scientific publications related to the ageing workforce.

Source: Authors’ computation based on 122 articles gathered from the Scopus database (data accessed on November 8, 2017)

To support the national welfare systems and to overcome the rising pressure on pension expenses, government agencies have proposed to prolong the working life of individuals (Froehlich et al. 2015; Loichinger and Skirbekk 2016). According to Finch (2014), raising the retirement age was the main policy plan of action for European Union countries in the mid of twenty-first century. As a result, the rising trend of scientific research to examine the issues related to the ageing workforce was more visible in the recent years (see Fig. 2).

For the most part, research studies in any field that are most frequently cited are likely to be considered as having the greatest impact in their respective field of study (Ferreira, 2011). Of the 122 reviewed articles relating to the ageing workforce from 1990 to 2018, we examined the ten most cited works (see Table 3). In the most frequently cited article, the topics of economics, ageing and health were examined in more depth. It is important to note that of the ten most frequently cited articles, five focused on economics: the issue of the ageing workforce through an economics lens was addressed by Brooks (2003), Greller and Simpson (1999), Schalk et al. (2010), Simpson et al. (2002) and Sterns and Miklos (1995), which suggests that there is strong interest in studying ageing workforces from an economics perspective. From the reviewed 122 articles, scientific work by Sterns and Miklos (1995) shows the highest citation (129 citations).

Table 3.

Ten most frequently cited articles among the reviewed articles

| Title | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Source | Year | Volume | No. citation | Focus of the article |

| 1.The aging worker in a changing environment: organizational and individual issues | |||||

| Sterns HL1, Miklos SM2 | Journal of Vocational Behavior | 1995 | 47 | 129 | Economics |

| 2.Employers and older workers: Attitudes and employment practices | |||||

| Taylor P1, Walker A2 | Ageing and Society | 1998 | 18 | 120 | Ageing |

| 3.Retirement patterns from career employment | |||||

| Cahill KE1, Giandrea MD2, Quinn JF3 | Gerontologist | 2006 | 46 | 110 | Ageing |

| 4.In search of late career: a review of contemporary social science research applicable to the understanding of late career | |||||

| Greller MM1, Simpson P2 | Human Resource Management Review | 1999 | 9 | 90 | Economics |

| 5.Moving European research on work and ageing forward: Overview and agenda | |||||

| Schalk R1, van Veldhoven M2, de Lange AH3, de Witte H4, Kraus K5, Stamov-Rosßnagel C6, Tordera N7, van der Heijden B8, Zappalà S9, Bal M10, Bertrand F11, Claes R12, Crego A13, Dorenbosch L14, de Jonge J15, Desmette D16, Gellert FJ17, Hansez I18, Iller C19, Kooij D20, Kuipers B21, Linkola P22, van den Broeck A23, van der Schoot E24, Zacher H25 | European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology | 2010 | 19 | 82 | Economics |

| 6.Variations in human capital investment activity by age | |||||

| Simpson PA1, Greller MM2, Stroh LK3 | Journal of Vocational Behavior | 2002 | 61 | 63 | Economics |

| 7.Health and safety needs of older worker | |||||

| Wegman DH1, McGee JP2 | Health and Safety Needs of Older Workers | 2004 | Book | 58 | Health |

| 8.Ageing, health and productivity: a challenge for the new millennium | |||||

| Griffiths A1 | Work and Stress | 1997 | 11 | 58 | Health |

| 9.Productive aging: an overview of the literature | |||||

| O’Reilly P1, Caro FG2 | Journal of Aging and Social Policy | 1995 | 6 | 55 | Ageing |

| 10.Human resource costs and benefits of maintaining a mature-age workforce | |||||

| Brooke L1 | International Journal of Manpower | 2003 | 24 | 54 | Economics |

The scientific importance of organizational factors on ageing workforce

Focusing on the issue of rising ageing populations, researchers such as Loichinger and Skirbekk (2016) stressed that countries which maintain longer working lives are in a better position to cope with this demographic change. An ageing population appears to have had a higher impact on industrialized western nations as they relied more on labour force participation (Schinner et al. 2017). Even though government agencies have determined that raising the retirement age is the most effective strategy, it is equally important to enquire whether older adults preferred to stay engaged in the labour market in order to address the shortages in the labour force. Therefore, increasing the statutory pension age is likely to be insufficient without additional measures that would encourage the ageing workforce to actively participate in the labour market (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015). Upon assessing the 122 peer-reviewed articles (full article), our findings highlight five primary organizational factors that support ageing workforces to stay engaged in the labour market with recommendations on how to sustain and improve their performance. As it relates to the ageing workforce–productivity nexus, articles were classified into the following categories: (1) health, (2) institution, (3) human resource management (HRM), (4) human capital and (5) technology tools. Table 4 presents in detail the definitions of the key organizational factors and indicates the relevant variables that have been considered as proxies for the factors by the literature.

Table 4.

Organizational factors that influence ageing workforce and the relevant proxies by the reviewed articles

| Organizational factors | Description | Proxies | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | Restores social benefits plan to prolong worker in the workforce | Pension, social insurance | Carmichael and Ercolani (2015) and Hennekam (2016) |

| Age-friendly work environment that assists in sustaining the performance of ageing workforce | Flexible working hours, optimal job rotation schedules, counselling services | Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald (2003), Boenzi et al. (2014), Killam and Weber (2014) and Ryan et al. (2017) | |

| Human capital | The role of education in shaping knowledge and experience among individual | Higher education | Badea and Rogojanu (2012) |

| Training increases worker productivity | Firm-sponsored classroom (FSC) training | Dostie and Léger (2014) | |

| Literacy and skill training are important for workers to maintain their productivity level. | Financial literacy, skill training | Clark et al. (2013) | |

| Training is an important strategy to retain older workers at work | On-the-job training | Picchio and Van Ours (2013) and Sarti and Torre (2018) | |

| Investment in post-schooling and trainings determined the current rate of technological change in the workplace | Post-schooling and training | Song (2012) and Sarti and Torre (2018) | |

| Work experiences contribute to the individuals’ development | Work experience | Venneberg and Wilkinson (2008) | |

| Human resource management | Workplace age stereotypes | Motivation level, participation in training and development, physical and mental fitness | Ng and Feldman (2012), Ravichandran et al. (2015), Bilinska et al. (2016) and Rego et al. (2017) |

| Age discrimination in the workplace | Conflict with young workers, treat older employee in fair manner | Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser (2011), Ravichandran et al. (2015), Bilinska et al. (2016) and Rego et al. (2017) | |

| Technology tools | Technology tools in the workplace may improve the performance of workforce | Digital human modelling, artificial intelligence | Choi (2009) and Case et al. (2015) |

| Ergonomic | Gonzalez and Morer (2016) | ||

| Promoting digital skills at the workplace (technology) | Information and communication technology | Lissitsa et al. (2017), Sarti and Torre (2018) | |

| Health | Physical exercises expected to delay the declines in the physical and cognitive functioning | Physical exercise | Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald (2003) |

| Flexible work arrangement to overcome musculoskeletal disorder pain | Minimize shift work for older employee, telework, rest break | Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser (2011), Mahesa et al. (2017) and Wendsche et al. (2016, 2017a, b) | |

| Frequent health observations to monitor the health conditions of older employees | Medical examination | Ryan et al. (2017), Hertel and Zacher (2018) |

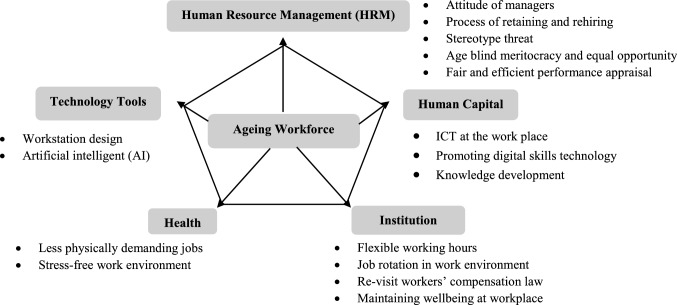

The variable health (“Health” section) looks at older workers’ physical and mental health issues in relation to work performance, and institution (“Institution” section) presents previous study findings on how private, public and non-profit institutions have dealt with an ageing workforce (Boenzi et al. 2014; Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Hennekam 2016). Human resource management (“Human resource management” section) captures managers’ and co-workers’ attitudes and behaviours towards older employees and the influences of such psychosocial characteristics on the ageing workforce (Bilinska et al. 2016; Ng and Feldman 2012; Ravichandran et al. 2015; Rego et al. 2017). Human capital (“Human capital” section) discusses the effectiveness of human capital investment (education, on-the-job training, willingness to embrace new technological knowledge and ICT training) among senior workers (Badea and Rogojanu 2012: Lissitsa et al. 2017; Sarti and Torre 2018). Finally, Technology tools (“Technology tools” section) describes the availability of technological assistance in the workplace, such as ergonomics and artificial intelligence (AI), to support ageing workers (Case et al. 2015; Choi 2009; Gonzalez and Morer 2016). The following section further discusses the importance of these factors on the engagement of the ageing workers in the workforce (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Organizational factors that influence the performance of the ageing workforce.

Source: Author’s design

Health

The physical and mental fitness of an individual is expected to diminish as a person ages (Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald 2003). According to Boenzi et al. (2014), physical health issues, such as decline in vision, hearing and muscle capacity, as well as reduced movement time, lung capacity and blood circulation, are likely to affect job performance. Hence, the intention of older workers to prolong their participation in the labour market is likely to be determined by injuries and illness incurred during their lifespan (Nilsson 2016; Wegman and McGee 2004). Furthermore, age-related decline in the selected aspects of cognitive functioning was also identified as a factor that affects job performance and other life activities of older people (Rast 2011; Rizzuto et al. 2012; Seidler et al. 2010). As a result, older adults’ poor health is expected to: (1) increase absenteeism, (2) lower productivity and (3) escalate health care needs (Wells et al. 2013). Research demonstrates that even though older workers in construction sectors make a significant contribution in terms of skills and experience, their physical health decline is likely to decrease their overall productivity (Choi 2009). Therefore, the engagement of older population with physical and mental health problems in the workforce often leads to a negative consequence to the employers (Wells et al. 2013). In addition, only physically and mentally fit older employees will express their willingness to participate in the labour market (Van Dam et al. 2016). Thus, it is important to have a sound understanding of the key factors that can support the health and well-being of seniors in the workplace before considering extending working age (Besen et al. 2015; Choi 2009; Wegman and McGee 2004; Yeh 2014).

Extant research discusses strategies for sustaining older employees’ health and well-being in workplace. Some literature proposed to reduce the work hours of the older employees as a way to prolong their participation in the workforce (Choi 2009; Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald 2003; Mahesa et al. 2017; Wegman and McGee 2004). Furthermore, according to Koopman-Boyden and Macdonald (2003), physical and intellectual training exercises during early age of working life are expected to delay the declines in the physical and cognitive functioning of the future ageing workforce. Apart from that, flexible work arrangements are also likely to improve the health and well-being of older employees (Mahesa et al. 2017; Yeh 2014). For example, minimizing shift work among older employees will reduce their physical health problems, such as musculoskeletal disorder pain (Mahesa et al. 2017). On top of minimizing shift work and flexible working hours, frequent medical examination helps to prolong the physical and mental fitness of older employees in the workforce (Ryan et al. 2017).

Institution

Government agencies in most developed countries have increased their statutory pension age (SPA) due to the consistent rise in older populations (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015). Majority of the Western nations such as Canada, the Netherlands and the UK have assumed that the increasing SPA would be an effective way to reduce aggregate pension expenses and increase the employment rate (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Hennekam 2016). For example, in the Netherlands, organizations no longer pay social benefits to employees over the age of 65 (Hennekam 2016). In fact, Hennekam (2016) reveals that the end of social benefits for employees over the age of 65 demonstrated positive effects on the employability of veterans at age 65 and above. However, some literature reports that increasing the retirement age alone would still render insufficiencies for addressing this challenge (Boenzi et al. 2014; Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Ryan et al. 2017). For example, as the majority of the tasks performed by older employees who work in assembly lines are a testament to their physical strength, increasing the production rate in an assembly line will expectantly affect the physical workloads of older employees (Boenzi et al. 2015a, b).

The type of institution can play an important role in facilitating the ageing workforce to perform effectively in the workforce. Taking into account the challenges faced by older populations to achieve high performance in the labour market, several researchers have suggested additional measures to enrich the productivity and employability of older populations. Workplace policy recommendations such as (1) additional training (Carmichael and Ercolani, 2015); (2) flexible working hours (Ryan et al. 2017); (3) optimal job rotation schedules (Boenzi et al. 2015a); (4) counselling services that help older workers adapt to changes in the work environment (Killam and Weber 2014); and (5) better work environment (that focuses on health and capability of the employee) (Boenzi et al. 2014) were proposed in literature to ensure the health and well-being of older employees.

Human resource management

Older workers frequently experience stereotype threat towards the young manager, young workgroup and manual occupation (Axelrad et al. 2013; Kulik et al. 2016; O’Reilly and Caro 1995). For example, older workers feel that their contributions to the workforce are not recognized by younger workers (Ravichandran et al. 2015; Rego et al. 2017). Rego et al. (2017) found that younger workers behave as though they are more superior, and are condescending towards older employees, as they often feel that they have more educational attainment and knowledge that are more “up to date”. Older workers also reported lack of support from their younger supervisors for their participation in training (Ravichandran et al. 2015). Hence, younger managers’ negative attitudes towards older workers have a significant impact on the continued employability of the senior population (Ravichandran et al. 2015; Rego et al. 2017). In addition, Armstrong-Stassen and Schlosser (2011) suggested that organizations educate younger supervisors on the importance of creating opportunities for older employees in a fair manner and treating them with respect and dignity.

Human capital

Even though it was demonstrated that encouraging the older population to remain in the labour market can help overcome the fall in employment rate, employers are still concerned over the productivity level of older employees (Göbel and Zwick 2013; Lisenkova et al. 2012). The prime objective of an employer is to obtain higher productivity at the lowest cost; hence, the majority of employers believed that employing an older worker would require an increase in production cost while decreasing productivity rate (Lisenkova et al. 2012). Despite the fact that the level of experience and knowledge held by the older population is found to have a positive impact on an organization’s development, the amount of physical and mental challenges that surround an older workforce (in terms of task performance) have shown a statistically negative effect on the productivity of a firm (Rocha 2017). Consequently, the majority of organizations feel that continuous employment of veterans will increase the gap between wage and productivity (Van Ours and Stoeldraijer 2011). For instance, firms in Brazil are paying older workers more than their marginal productivity (Rocha 2017).

Taking into consideration employers’ concerns about the productivity of an ageing workforce, some research has proposed to invest in training programs that particularly help older workers be more competitive in the workforce (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Rocha 2017; Zboralski-Avidan 2015;). In fact, increasing training participation of senior workers at age 55–59 has shown a positive impact on their performance (Zboralski-Avidan 2015). Nevertheless, Carmichael and Ercolani (2015) found that training rates across European countries have declined considerably with age. According to Carmichael and Ercolani (2015) and Jeske and Roßnagel (2015), the majority of the employers are willing to provide more training opportunities to younger workers as this will help them retain their position in the job for an extensive period. Apart from fewer opportunities, in most situations, older workers are also less motivated to undertake work-related training (Carmichael and Ercolani 2015). Conversely, in the USA, older workers from food service industries have expressed a high interest in attending on-the-job training as they believe that it would be beneficial to their performance (Ravichandran et al. 2015).

Lastly, the perception of older workers’ learning capabilities requires change among both employers and younger employees, as this will increase older workers’ participation in training programs (Jeske and Roßnagel 2015; Schinner et al. 2017; Schloegel et al. 2016). Indeed, the willingness (by both employers and workers) to adapt to technological advancements and changes and provide technological training will enable the ageing workforce to contribute effectively in organizations (Schinner et al. 2017). For example, a cooperation-based workshop with 74 employees (average age of 53) from China demonstrated better performance of older employees on software development (Schloegel et al. 2016). In conclusion, job training and technology skills development for senior workers may decrease the issue of productivity that is associated with age-related challenges.

Technology tools

In order to sustain the participation of older populations in the labour market, the role of technology tools is considered equally important compared to other organizational factors. For instance, according to Case et al. (2015), appropriate ergonomic techniques for older workers to adjust to their work environment are likely to contribute to their productivity level. Furthermore, the assistance of a technology is expected to reduce the productivity pay gap seen among older workers (Case et al. 2015). Additionally, the use of technology tools, such as artificial intelligent and ergonomic, in the workplace may improve work health and create a safer environment (Case et al. 2015; Choi, 2009). Case et al. (2015) indicated that the implementation of digital human modelling techniques in the manufacturing sector enabled older workers to perform their tasks better.

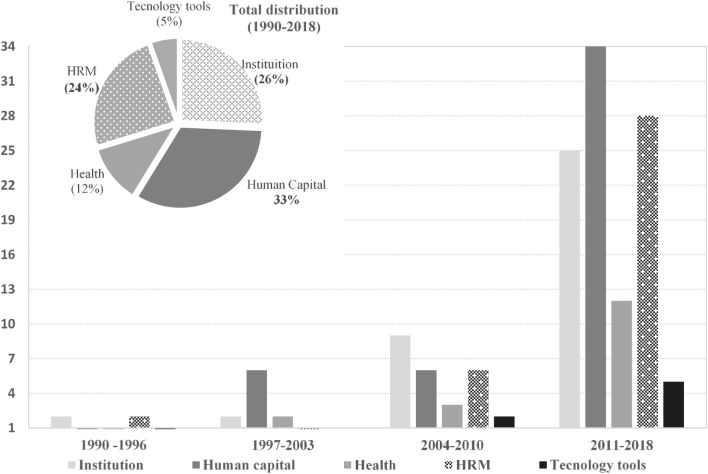

In some situations, experts face challenges when designing work environments that encompass both older and younger workers. For instance, Gonzalez and Morer (2016) highlighted in their study that ergonomists experienced more user-sensitivity issues, especially when designing work environments for both older and younger workers. Hence, in certain work environments, it is important to address the requirements that are suitable for both older and younger people. Despite the important role of technology tools for the ageing workforce, to the best of our knowledge, we found that the contribution of this factor in accommodating older employees in the workplace has been less explored (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Evolution of the organizational factors of the ageing workforce.

Source: Authors’ computation based on 122 articles (148 occurrences) via the Scopus database (Data was accessed on November 8, 2017)

The evolution of the organizational factors of the ageing workforce

Countries with a growing ageing population will inevitably experience a constant rise in the ageing workforce. In the previous section, we identified five key organizational factors that are often considered as a way to assist the performance of an ageing workforce: health, institution, human capital, human resource management (HRM) and technology tools. Our bibliometric survey results (see Fig. 4) revealed that human capital was the most frequently analysed in the literature. For example, studies conducted by Zimmer et al. (2015) and Sarti and Torre (2018) suggest that information and communication technology (ICT) training for older workers would help them to become more competitive in terms of their performance compared to their younger counterparts.

Aside from human capital, researchers and employers also pay more attention to the institution and HRM. Since increasing the retirement age is expected to positively influence government revenue (Tosun 2003), the latest retirement policies may have led researchers to focus on institutions and HRM.

Our bibliometric survey also found that technology tools were least considered (5%) among the five factors. Since the operating process of a firm varies within and between the sectors, the design of work environments is unique to each organization (Gonzalez and Morer 2016). Therefore, the design process and implementation using technology can be particularly time-consuming, which may explain the limited number of articles focused on ergonomics and ageing workforce studies. Finally, we concluded that during the period of analysis, organizational factors such as “human capital (33%)”, “institution (26%)” and “HRM (24%)” were demonstrated as immediate factors to enable and facilitate high performance in an ageing workforce.

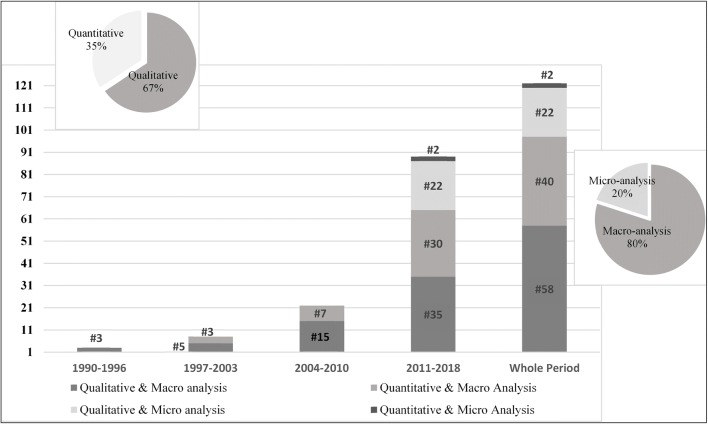

The methodological evolution of research on the ageing workforce

For the period analysed, approximately 67% of the research focused on qualitative analysis, whereas 35% used quantitative methods (see Fig. 5). Majority of the research was conducted by surveys, appreciative, scoping reviews and environmental scans. However, Kaldor (1961) stressed that the increased attention to quantitative analysis, accompanied by real-life information, would provide context alongside statistically more relevant explanations to the research featuring economic variables. However, since the “wicked problem” of an ageing workforce is complex, to scientifically study the ageing workforce and all its challenges requires a mixed methods approach that can provide more information than through qualitative methods alone.

Fig. 5.

Evolution of scientific publications on methodological approaches used in the reviewed articles.

Source: Authors’ computation based on 122 articles gathered from the Scopus database (Nov. 8, 2017)

Our bibliometric survey results also found that the researchers focused more on macro-level analyses while the empirical studies included in our final subset focused mainly on developed countries, such as USA (Elias et al. 2012; Wells et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2015; Zimmer et al. 2015; Earl et al. 2017), Europe (Bosch and Ter Weel 2013; Carmichael and Ercolani 2015; Earl et al. 2017; Eichhorst et al. 2014; Göbel and Zwick 2013; Gonzalez and Morer 2016; Guerrazzi 2014; Kroon et al. 2017; Kulik et al. 2016), United Kingdom (Fuertes et al. 2013), Australia (Graham et al. 2014), New Zealand (Poulston and Jenkins 2013) and Japan (Earl et al. 2017). However, there were only a few studies that investigated developing countries such as China (Earl et al. 2017; Schloegel et al. 2016), Brazil (Gerpott et al. 2017) and India (Earl et al. 2017).

Among the microanalytical studies, the majority of the researchers used techniques such as interviews and questionnaires to identify differences in the perceptions between managers and older workers (Hennekam, 2016; Poulston and Jenkins 2016; Schloegel et al. 2016). Schloegel et al. (2016) stressed that the behavioural-based information enabled the determination of attitudes and changes among employees from different groups. Finally, as indicated in Fig. 5, we could conclude that there is a higher need for research using quantitative analyses that mainly focus on using micro-level data.

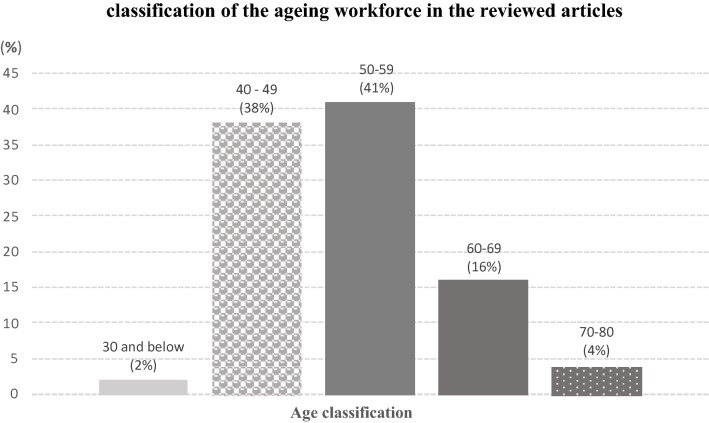

The scientific age classification of the ageing workforce

The literature related to ageing populations was a popular topic since early 2000 (Eurostat 2013; Lee et al. 2011; Nagarajan et al. 2017; Weil 2006). Due to this, the strategy of government agencies to increase the retirement age was more evident since mid-2000. The process of defining the age groups depends on the age distribution of populations at the time (Albis and Collard 2013; Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer 2006). Thus, during this time frame, most of the empirical studies had classified employee age groups 40–49 and 50–59 as senior workers and focused on analysing their performance in the labour market. In fact, from the year 1990 onwards, 41% of the published articles had considered age group 50–59 for their empirical studies (see Fig. 6). Over a decade ago, older workers were classified between age 50 and older (Macnicol 2008) and the majority of research focused on these particular age groups. For instance, in 2007, the median average age of workforce in America was 41 years old (NCPERS 2003). Subsequently, the rise in life expectancy in developed countries since 2010 (Nagarajan et al. 2017) establishes the importance of increasing the retirement age (Hurd and Rohwedder 2011; Okumura and Usui 2014; Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer 2006).

Fig. 6.

Age classification of the ageing workforce in the reviewed articles.

Source: Authors’ computation based on 122 articles gathered from the Scopus database (Data was accessed on November 8, 2017)

Moreover, many developed countries like Canada expect to experience a growing ageing population due to the retirement of baby boomers (Fougère et al. 2009; Sharpe 2011). Hence, unlike the previous retirement age trend, the presence of an ageing population in such countries has influenced the retirement age to increase to 67 years old (Bernal and Vermeulen 2014). Since the retirement age was more recently increased to 65 years above in many countries, during the period from 1990 to 2018, only 16% of the published articles considered older employees at age 60–69 for empirical analyses (see Fig. 6).

Final remarks regarding the ageing workforce

Discussion

The constant rise in the life expectancy and fall in the fertility rate have increased the proportion of the ageing population over young population. This demographic transition permits the ageing population to be considered as a dominant population. However, this imbalance in the age structure has gradually reduced the supply of labour in the workforce, increased the government pension expenses and decreased the aggregate household consumption pattern. To overcome the effect of the ageing population, researchers and policymakers introduced the world to the era of “silver economy”, which was particularly focused on allowing the ageing population to actively engage in economic activities. Currently, many developments are expected to fall within the silver economy umbrella. Currently, many developments are expected to fall within the silver economy umbrella, primarily, to develop a better solution to address one or more of the following issues associated with ageing processes: cost of direct and indirect health care; physical and cognitive decline; and fall in the labour supply. Increasing the retirement age is one of the policy changes that is expected to positively contribute to the development of the new “silver economy”. However, seniors in the workforce are often stigmatized by perceptions of their diminishing health (Chien and Lin 2012; Murphy et al. 2006) and their “out-of-date” technological knowledge, despite the obvious structural contributors to poor employee health often determined by the leader’s ethos and behaviour within organizations (Wegge et al. 2014).

In addition to retaining senior workers (despite any health-related issues), creating diversified, age teams in the workplace is a major challenge (Liebermann et al. 2013; Wegge et al. 2008). Young team members in age-diverse teams are less likely to perform at optimum levels if they hold negative, stereotypical views about their older colleagues (Liebermann et al. 2013). Given the important role of the ageing workforce in the labour market, it is necessary to create a sustaining age-diverse teams in the workplace.

In this paper, based on the bibliometric methodology, we have identified several dimensions regarding scientific contribution in the literature that focuses on the ageing workforce. Some of our findings deserve to be highlighted as they provide valuable inputs in examining the challenges and opportunities faced by the ageing workforce at the organizational level. First, the results confirm that there is an increasing pattern in the literature related to the ageing workforce, which demonstrates that there is more literature after 2010. Second, we have identified five main organizational factors (health, institution, human resource management (HRM), human capital and technology tools) that contribute to the participation of the older population in the labour market at the organizational level.

Third, in terms of these main factors, human capital was the most frequently analysed in the literature, whereas the importance of technology tools in assisting the ageing workforce was focused on less. Finally, the vast majority of the study had concentrated on macro-level analyses of the empirical studies that had considered employee age groups 40–49 and 50–59 as senior workers. Macro-analyses focus more on general statements (Karl-Dieter 2011), as their name suggests, and have proven to be less effective in contexts that are inherently heterogeneous in nature, such as ageing (Berkman 1988). Hence, taking into consideration the increase in retirement age in combination with the heterogeneous nature of ageing, future research should include more employees aged 60 and above in their studies to examine the challenges they face in their efforts to remain in the labour market. Table 5 further summarizes the gaps in the reviewed scientific literature that require further attention in this context.

Table 5.

Gaps in the reviewed articles

| Present work | Gaps identified | Future work | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of scientific research works • Year 1990 to 2009 an average of 1.2 articles per year. • Year 2010 to 2018 an average of 10.9 articles per year. Organizational factors that influence the participation of ageing workforces • Health • Institution • Human resource management (HRM) • Human capital • Technology tools Methodological Considerations • Quantitative • Qualitative Age classification • 30 years and above (2%) • 40–49 years old (38%) • 50–59 years old (41%) • 60–69 years old (16%) • 70–80 years old (4%) |

|

Ageing workforce is an important topic in this twenty-first century, and there is a gap in the scientific research work • Technology tools in assisting the ageing workforce were less explored • Qualitative research focuses more on systematic review (Scoping review, environmental scanning, literature review) and case study method (e.g. interviewing ageing workers) was less studied • Researchers have less focused on micro-analysis • Employees age 60 and above were less considered for empirical studies. |

|

Primary Action • Life expectancy, baby boomers, rise in retirement age evidence on the need for more research on ageing workforce Secondary action • Technology tools are an important factor that assist ageing workers to be productivity • As the term “ageing workers” changes with the rise in the retirement age, future research should include employee age 60 and above • Ageing population are heterogenous and the needs and preferences to remain in the workforce may vary. Hence, to better understand the various needs and preferences, qualitative research is needed (e.g. case study) |

The present research has limitations that offer opportunities for future investigation. Key limitations of the bibliometric analysis constitute the exclusion grey literature and sources that were written in non-English languages. Accordingly, the current quantitative analysis via the bibliometric method focused on quantifying peer-reviewed articles, which excluded potentially relevant grey sources (i.e. research not published in an academic journal). Grey literature is equally important as, often, it includes policy documents and organizational reports, which is relevant for ageing workforce study. As well, research reported in other languages can provide greater insight into the cultural nuances that most certainly influence the ageing workforce. Future review studies of this kind can address these gaps by including grey sources, such as reports, case studies and policy documents, and/or with a specific focus on a language besides English, in order to further contextualize and generate more holistic and in-depth knowledge on this topic area. Lastly, it is important to note that this study did not review literature on individual-level factors. As a result, promising individual-level interventions that concurrently influence older workers’ engagement in workforce were not discussed. Future work requires an examination of potential individual-level factors that impact older adults’ decision on whether or not to (re-)engage in the workforce. A focused investigation on individual-level factors would provide for more holistic understandings on how to better support older workers to remain and possibly re-enter the labour market.

Conclusion

Overall, our bibliometric analysis has not only confirmed the importance of the ageing workforce but has also identified the main organizational factors that could assist senior workers to be more productive in the labour market. Furthermore, since the current retirement age of senior workers has been revised to 65 years old, there is a growing need to consider senior workers who are 60 years old and/or older for the empirical studies. Finally, taking into account the significant role of the senior population in overcoming the issue of labour shortages, adequate policy proposals through the five organizational factors are expected to have a positive effect on retaining senior workers in the labour market.

Appendix

Reviewed articles

Sarti D, Torre T (2018) Generation X and knowledge work: The impact of ICT. What are the implications for HRM? Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation 23: 227–240.

Lissitsa S, Chachashvili-Bolotin S, Bokek-Cohen Y (2017) Digital skills and extrinsic rewards in late career. Technology in Society 51: 46–55.

Kowalski THP, Loretto W (2017) Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. International Journal of Human Resource Management 28: 2229–2255.

Rego A, Vitória A, Cunha MPE, Tupinambá A, Leal S (2017) I Developing and validating an instrument for measuring managers’ attitudes toward older workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management 28: 1866–1899.

Kroon AC, Vliegenthart R, van Selm M (2017) Between accommodating and activating: framing policy reforms in response to workforce aging across Europe. International Journal of Press/Politics 22: 333–356.

Ryan C, Bergin M, Wells JS (2017) Valuable yet Vulnerable—A review of the challenges encountered by older nurses in the workplace. International Journal of Nursing Studies 72: 42–52.

Gerpott FH, Lehmann-Willenbrock N, Voelpel SC (2017) A phase model of intergenerational learning in organizations. Academy of Management Learning and Education 16: 193–216.

Mahesa RR, Vinodkumar MN, Neethu V (2017) Modeling the influence of individual and employment factors on musculoskeletal disorders in fabrication industry. Human Factors and Ergonomics In Manufacturing 27: 116–125.

Rocha R (2017) Aging, productivity and wages: Is an aging workforce a burden to firms? Espacios 38: 21–33.

Schinner M, Valdez AC, Noll E, Schaar AK, Letmathe P, Ziefle M (2017) Industrie 4.0’ and an aging workforce—a discussion from a psychological and a managerial perspective. in: Zhou J, Salvendy G (eds) Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Applications, Services and Contexts. ITAP 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 10298: 537–556.

Earl C, Taylor P, Roberts C, Huynh P, Davis S (2017) The workforce demographic shift and the changing nature of work: Implications for policy, productivity, and participation. Advanced Series in Management 17: 3–34.

Sammarra A, Profili S, Maimone F, Gabrielli G (2017) Enhancing knowledge sharing in age-diverse organizations: The role of HRM practices. Advanced Series in Management 17: 161–187.

Kulik CT, Perera S, Cregan C (2016) Engage me: The mature-age worker and stereotype threat. Academy of Management Journal 59: 2132–2156.

Palm K (2016) A case of phased retirement in Sweden. In Ordoñez de Pablos P, Tennyson R (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Human Resources Strategies for the New Millennial Workforce, PP 351–370.

Schloegel U, Stegmann S, Maedche A, van Dick R (2016) Reducing age stereotypes in software development: The effects of awareness- and cooperation-based diversity interventions. Journal of Systems and Software 121: 1–15.

Wanberg CR, Kanfer R, Hamann DJ, Zhang Z (2016) Age and reemployment success after job loss: An integrative model and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 142: 400–426.

Hollis-Sawyer L, Dykema-Engblade A (2016) Women and Positive Aging: An International Perspective. Women and Positive Aging: An International Perspective, PP 1–352.

Poulston J, Jenkins A (2016) Barriers to the employment of older hotel workers in New Zealand. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism 15: 45–68.

Hennekam S (2016) Employability and performance: a comparison of baby boomers and veterans in The Netherlands. Employee Relations 38: 927–945.

Loichinger E, Skirbekk V (2016) International variation in ageing and economic dependency: A cohort perspective. Comparative Population Studies 41: 121–144.

Nilsson K (2016) Conceptualisation of ageing in relation to factors of importance for extending working life - A review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 44: 490–505.

Ng ES, Parry E (2016) Multigenerational research in human resource management. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management 34: 1–41.

Van Dam K, van Vuuren T, van der Heijden BIJM (2016) Sustainable labour participation of older employees: A review [De duurzame inzetbaarheid van oudere werknemers: Een overzicht]. Gedrag en Organisatie 29: 3–27.

Gonzalez I, Morer P (2016) Ergonomics for the inclusion of older workers in the knowledge workforce and a guidance tool for designers. Applied Ergonomics 53: 131–142.

Yang T, Shen YM, Zhu M, Liu Y, Deng J, Chen Q, See LC (2015) Effects of co-worker and supervisor support on job stress and presenteeism in an aging workforce: A structural equation modelling approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13: 1–15.

Carmichael F, Ercolani MG (2015) Age-training gaps across the European Union: How and why they vary across member states. Journal of the Economics of Ageing 6: 163–175.

Zboralski-Avidan H (2015) Further training for older workers: A solution for an ageing labour force? Further Training for Older Workers: A Solution for an Ageing Labour Force? (Doctoral dissertation, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. Retrieved from Dissertation Online at the Freie Universität Berlin. http://www.diss.fu-berlin.de/diss/receive/FUDISS_thesis_000000098212?lang=en, accessed on: 26.12.2017.

Cahill KE, Giandrea MD, Quinn JF (2015) Chapter 13 - Evolving Patterns of Work and Retirement. In Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences: Eighth Edition, PP 271–291.

Park J, Kim S (2015) The differentiating effects of workforce aging on exploitative and exploratory innovation: The moderating role of workforce diversity. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 32: 481–503.

Boenzi F, Digiesi S, Mossa G, Mummolo G, Romano VA (2015) Modelling workforce aging in job rotation problems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 48: 604–609.

Zimmer JC, Tams S, Craig K, Thatcher J, Pak R (2015) The role of user age in task performance: examining curvilinear and interaction effects of user age, expertise, and interface design on mistake making. Journal of Business Economics 85: 323–348.

Matt SB, Fleming SE, Maheady DC (2015) Creating Disability Inclusive Work Environments for Our Aging Nursing Workforce. Journal of Nursing Administration 45: 325–330.

Yen SH, Lim HE, Campbell JK (2015) Age and productivity of academics: A case study of a public university in Malaysia. Malaysian Journal of Economic Studies 52: 97–116.

Case K, Hussain A, Marshall R, Summerskill S, Gyi D (2015) Digital Human Modelling and the Ageing Workforce. Procedia Manufacturing 3: 3694–3701.

Duffield C, Graham E, Donoghue J, Griffiths R, Bichel-Findlay J, Dimitrelis S (2015) Why older nurses leave the workforce and the implications of them staying. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24: 824–831.

Boenzi F, Mossa G, Mummolo G, Romano VA (2015) Workforce aging in production systems: Modeling and performance evaluation. Procedia Engineering 100: 1108–1115.

Ravichandran S, Cichy KE, Powers M, Kirby K (2015) Exploring the training needs of older workers in the foodservice industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management 44: 157–164.

Besen E, Matz-Costa C, James JB, Pitt-Catsouphes M (2015) Factors buffering against the effects of job demands: How does age matter? Journal of Applied Gerontology 34: 73–101.

Bieling G, Stock RM, Dorozalla F (2015) Coping with demographic change in job markets: How age diversity management contributes to organisational performance. Zeitschrift fur Personalforschung 29: 5–30.

Jeske D, Roßnagel CS (2015) Learning capability and performance in later working life: Towards a contextual view. Education and Training 57: 378–391.

Froehlich DE, Beausaert SAJ, Segers MSR (2015) Age, employability and the role of learning activities and their motivational antecedents: a conceptual model. International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 2087–2101.

Eichhorst W, Boeri T, De Coen A, Galasso V, Kendzia M, Steiber N (2014) How to combine the entry of young people in the labour market with the retention of older workers? IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 3: 1–23.

Parker M, Acland A, Armstrong HJ, Bellingham JR, Bland J, Bodmer HC, Burall S, Castell S, Chilvers J, Cleevely DD, Cope D, Costanzo L, Dolan JA, Doubleday R, Feng WY, Godfray HCJ, Good DA, Grant J, Green N, Groen AJ, Guilliams TT, Gupta S, Hall AC, Heathfield A, Hotopp U, Kass G, Leeder T, Lickorish FA, Lueshi LM, Magee C, Mata T, McBride T, McCarthy N, Mercer A, Neilson R, Ouchikh J, Oughton EJ. Oxenham D, Pallett H, Palmer J, Patmore J, Petts J, Pinkerton J, Ploszek R, Pratt A, Rocks SA, Stansfield N, Surkovic E, Tyler CP, Watkinson AR, Wentworth J, Willis R, Wollner PKA, Worts K, Sutherland WJ (2014) Identifying the science and technology dimensions of emerging public policy issues through horizon scanning. PLoS ONE 9: e96480.

Boenzi F, Mossa G, Mummolo G, Romano VA (2014) Evaluating the effects of workforce aging in human-based production systems: A state of the art. Proceedings of the XIX Summer School Francesco Turco (Conference Paper), Senigallia, Italy, September 9–12.

Yeh WY (2014) Age differences in physical and mental health conditions and workplace health promotion needs among workers: An example of accommodation and catering industry employees. Gerontechnology 13: 313–313.

Tikkanen T (2014) Lifelong learning and skills development in the context of innovation performance: In: Schmidt-Hertha B., Krašovec S.J., Formosa M. (eds) Learning across Generations in Europe. Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, SensePublishers, Rotterdam, PP 95–120.

Guerrazzi M (2014) Workforce ageing and the training propensity of Italian firms Cross-sectional evidence from the INDACO survey. European Journal of Training and Development 38: 803–821.

Martin G, Dymock D, Billett S, Johnson G (2014) In the name of meritocracy: Managers’ perceptions of policies and practices for training older workers. Ageing and Society 34: 992–1018.

Killam W, Weber B (2014) Career adaptation wheel to address issues faced by older workers. Adultspan Journal 13: 68–78.

Maikala RV, Cavuoto LA, Maynard WS, Fox RR, Lin JH, Liu J, Lavallière M (2014) Aging, obesity and beyond: Implications for healthy work environment. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 58th annual meeting. PP 1648–1652.

Graham E, Donoghue J, Duffield C, Griffiths R, Bichel-Findlay J, Dimitrelis S (2014) Why do older RNs keep working? Journal of Nursing Administration 44: 591–597.

Hashim J, Wok S (2014) Competence, performance and trainability of older workers of higher educational institutions in Malaysia. Employee Relations 36: 82–106.

Tams S, Grover V, Thatcher J (2014) Modern information technology in an old workforce: Toward a strategic research agenda. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 23: 284–304.

Axelrad H, Luski I, Miki M (2013) Difficulties of integrating older workers into the labor market: Exploring the Israeli labor market. International Journal of Social Economics 40: 1058–1076.

Reynolds F, Farrow A, Blank A (2013) Working beyond 65: A qualitative study of perceived hazards and discomforts at work. Work 46: 313–323.

Karpinska K, Henkens K, Schippers J (2013) Retention of older workers: Impact of Managers’ age norms and stereotypes. European Sociological Review 29: 1323–1335.

Marchant T (2013) Keep going: career perspectives on ageing and masculinity of self-employed tradesmen in Australia. Construction Management and Economics 31: 845–860.

Wells-Lepley M, Swanberg J, Williams L, Nakai Y, Grosch JW (2013) The Voices of Kentucky Employers: Benefits, Challenges, and Promising Practices for an Aging Workforce. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 11: 255–271.

Göbel C, Zwick T (2013) Are personnel measures effective in increasing productivity of old workers? Labour Economics 22: 80–93.

Bosch N, ter Weel B (2013) Labour-Market Outcomes of Older Workers in the Netherlands: Measuring Job Prospects Using the Occupational Age Structure. Economist (Netherlands) 161: 199–218.

Fuertes V, Egdell V, McQuaid R (2013) Extending working lives: Age management in SMEs. Employee Relations 35: 272–293.

Poulston J, Jenkins A (2013) The Persistent Paradigm: Older Worker Stereotypes in the New Zealand Hotel Industry. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality and Tourism 12: 1–25.

Hsu YS (2013) Training older workers: A review. In Field J, Burke RJ, Cooper CL, The SAGE handbook of aging, work and society, PP 283–299.

Wang M, Olson DA, Shultz KS (2012) Mid and late career issues: An integrative perspective. Mid and Late Career Issues: An Integrative Perspective New York: Routledge, PP 1- 240.

Hedge JW, Borman WC (2012) Work and Aging. The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, PP 1–744.

Elias SM, Smith WL, Barney CE (2012) Age as a moderator of attitude towards technology in the workplace: Work motivation and overall job satisfaction. Behaviour and Information Technology 31: 453–467.

Dymock D, Billett S, Klieve H, Johnson GC, Martin G (2012) Mature age ‘white collar’ workers’ training and employability. International Journal of Lifelong Education 31: 171–186.

Greller MM (2012) Workforce Planning with an Aging Workforce, in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 365–379.

Gutman A (2012) Age-Based Laws, Rules, and Regulations in the United States, in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 606–628.

Sharit J, Czaja SJ (2012) Job Design and Redesign for Older Workers. in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 545–482.

Allen TD, Shockley KM (2012) Older Workers and Work-Family Issues. in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 520–537.

Thompson LF, Mayhorn CB (2012) Aging Workers and Technology. in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 341- 364.

Rizzuto TE, Cherry KE, LeDoux JA (2012) The Aging Process and Cognitive Capabilities. in Hedge, JW, Borman WC (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, PP 236–255.

Göbel C, Zwick T (2012) Age and Productivity: Sector Differences. Economist 160: 35–57.

Cho YJ, Lewis GB (2012) Turnover Intention and Turnover Behavior: Implications for Retaining Federal Employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration 32: 4- 23.

Williams van Rooij S (2012) Training older workers: Lessons learned, unlearned, and relearned from the field of instructional design. Human Resource Management 51: 281–298.

Cleveland JN, Lim AS (2012) Employee age and performance in organizations. In Shultz KS, Adams GA (Eds.) Aging and Work in The 21st Century, PP 109–137.

Bowen CE, Noack MG, Staudinger UM (2011) Aging in the Work Context. In Schaie KW, Willis SL (Eds.) Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, PP 263–277.

Roßnagel CS, Baron S, Kudielka BM, Schömann K (2011) A competence perspective on lifelong workplace learning. In Margaret PC (Eds.) Handbook of Lifelong Learning Developments. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Frosch K, Göbel C, Zwick T (2011) Separating wheat and chaff: age-specific staffing strategies and innovative performance at the firm level [Den Weizen von der Spreu trennen—Altersbezogene Personalpolitik und Innovationen auf der Betriebsebene]. Journal for Labour Market Research 44: 321–338.

Meyer J (2011) Workforce age and technology adoption in small and medium-sized service firms. Small Business Economics 37: 305–324.

Rizzuto TE (2011) Age and technology innovation in the workplace: Does work context matter? Computers in Human Behavior 27: 1612–1620.

Peltokorpi V (2011) Performance-related reward systems (PRRS) in Japan: Practices and preferences in Nordic subsidiaries. International Journal of Human Resource Management 22: 2507–2521.

Kaarst-Brown ML, Birkland JLH (2011) Researching the older it professional: Methodological challenges and opportunities. SIGMIS CPR 2011 - Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGMIS Computer Personnel Research Conference, PP 113–118.

Van Ours JC, Stoeldraijer L (2011) Age, wage and productivity in Dutch manufacturing. Economist 159: 113–137.

Cataldi A, Kampelmann S, Rycx F (2011) Productivity-Wage gaps among age groups: Does the ICT environment matter? Economist 159:193–221.

Marshall VW (2011) A life course perspective on information technology work. Journal of Applied Gerontology 30: 185–198.

Armstrong-Stassen M, Schlosser F (2011) Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 32: 319–344.

Schacht S, Maedche A (2010) On enterprise information systems addressing the demographic change. Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, Volume 3, ISAS, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal.

Žnidaršič J (2010) Age management in Slovenian enterprises: The viewpoint of older employees. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakultet au Rijeci 28: 271–301.

Zülch G, Becker M (2010) Impact of ageing workforces on long-term efficiency of manufacturing systems. Journal of Simulation 4: 260–267.

Hofäcker D (2010) Older workers in a globalizing world: An international comparison of retirement and late-career patterns in western industrialized countries. Older Workers in a Globalizing World: An International Comparison of Retirement and Late-Career Patterns in Western Industrialized Countries, PP 1–317.

Roßnagel CS, Baron S, Kudielka BM, Schömann K (2010) A competence perspective on lifelong workplace learning. Professions—Training, Education and demographics, PP 1–56.

Taylor P, Jorgensen B, Watson E (2010) Population ageing in a globalizing labour market: Implications for older workers. China Journal of Social Work 3: 259–272.

Graham EM, Duffield C (2010) An ageing nursing workforce. Australian Health Review 34: 44–48.

Clark RL, Ogawa N, Kondo M, Matsukura R (2010) Population decline, labor force stability, and the future of the Japanese economy. European Journal of Population 26: 207–227.

Shultz KS, Wang M, Crimmins EM, Fisher GG (2010) Age differences in the demand-control model of work stress: An examination of data from 15 European countries. Journal of Applied Gerontology 29: 21–47.

Schalk R, van Veldhoven M, de Lange AH, de Witte H, Kraus K, Stamov-Rosßnagel C, Tordera N, van der Heijden B, Zappalà S, Bal M., Bertrand F, Claes R, Crego A, Dorenbosch L, de Jonge J, Desmette D, Gellert FJ, Hansez I, Iller C, Kooij D, Kuipers B, Linkola P, van den Broeck A, van der Schoot E, Zacher H (2010) Moving European research on work and ageing forward: Overview and agenda. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 19: 76–101.

Choi SD (2009) Safety and ergonomic considerations for an aging workforce in the US construction industry. Work 33: 307–315.

Zientara P (2009) Employment of older workers in polish SMEs: Employer attitudes and perceptions, employee motivations and expectations. Human Resource Development International 12: 135–153.

Faurie I, Fraccaroli F, Le Blanc A (2008) Age and work: From the studies on ageing in work to a psychosocial approach to the late career [Âge et travail: Des études sur le vieillissement au travail à une approche psychosociale de la fin de la carrière professionnelle]. Travail Humain 71: 137–172.

Liu S, Fidel R (2007) Managing aging workforce: Filling the gap between what we know and what is in the system. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series 232, PP 121- 128.

Eglit HC (2007) Age in the Workplace in the United-States [L’âge dans le monde du travail aux états-unis]. Retraite et Societe 51: 43–75.

Hursh N, Lui J, Pransky G (2006) Maintaining and enhancing older worker productivity. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 25: 45–55.

Ashworth MJ (2006) Preserving knowledge legacies: Workforce aging, turnover and human resource issues in the US electric power industry. International Journal of Human Resource Management 17: 1659–1688.

Guthrie R (2006) Workers’ compensation and age discrimination in Australia. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 8: 145–168.

Cahill KE, Giandrea MD, Quinn JF (2006) Retirement patterns from career employment. Gerontologist 46:514–523.

Bruyère SM (2006) Disability Management: Key Concepts and Techniques for an Aging Workforce. International Journal of Disability Management 1:149–158.

Gringart E, Helmes E, Speelman CP (2005) Exploring attitudes toward older workers among Australian employers: An empirical study. Journal of Aging and Social Policy 17: 85–103.

Joël ME (2005) Market and ageing [Marchés et vieillissement]. Revue d’Epidemiologie et de Sante Publique 53: 251–256.

National Research Council and the Institute of medicine. (2004) Health and Safety Needs of Older Workers. Wegman DH, McGee JP (Eds.) Division of behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academic Press.

Brooke L. (2003) Human resource costs and benefits of maintaining a mature-age workforce. International Journal of Manpower 24: 260–283.

Koopman-Boyden PG, Macdonald L (2003) Ageing, Work Performance and Managing Ageing Academics. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 25: 29–41.

Yamada Y, Konosu H, Morizono T, Umetani Y (2002) Proposal of Skill-Assist for mounting operations in automobile assembly processes. Nippon Kikai Gakkai Ronbunshu, C Hen/Transactions of the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers, Part C 68: 509–516.

Simpson PA, Greller MM, Stroh LK (2002) Variations in human capital investment activity by age. Journal of Vocational Behavior 61: 109–138.

Greller MM, Simpson P (1999) In Search of Late Career: A Review of Contemporary Social Science Research Applicable to the Understanding of Late Career. Human Resource Management Review 9: 309–347.

Taylor P, Walker A (1998) Employers and older workers: Attitudes and employment practices. Ageing and Society 18: 641–658.

Larwood L, Ruben K, Popoff C, Judson DH (1997) Aging, retirement, and interest in technological retraining: Predicting personal investment and withdrawal. Journal of High Technology Management Research 8: 277–300.

Griffiths A (1997) Ageing, health and productivity: A challenge for the new millennium. Work and Stress 11: 197–214.

O’Reilly P, Caro FG (1995) Productive aging: An overview of the literature. Journal of Aging and Social Policy 6: 39–71.

Sterns HL, Miklos SM (1995) The aging worker in a changing environment: Organizational and individual issues. Journal of Vocational Behavior 47: 248–268.

Whittaker DH (1990) The End of Japanese-Style Employment? Work Employment & Society 4: 321–347.

Table 6.

Coding techniques on the age classification

| No. | Year | Age classification | No. | Year | Age classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2017 | 45–65 | 59 | 2013 | 45–60 |

| 4 | 2017 | Managers mean age: 42; retirees mean age: 67.2 | 60 | 2013 | 40–64 |

| 9 | 2017 | 65 and above | 61 | 2013 | 50 and above |

| 15 | 2016 | 53 years old. | 62 | 2013 | 45 and above |

| 18 | 2016 | 60 and above | 65 | 2012 | 44 and above |

| 19 | 2016 | 60 and above | 66 | 2012 | 45–64 |