Abstract

Background:

Both European and American trials showed superior effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA) to placebo. However, the latter, which included black patients with known higher vitaminD3 deficiency risk, showed lower rate of amenorrhea responders and insignificant uterine fibroid (UF) size reduction. Our objective is to investigate whether adding vitamin D3 to UPA can enhance UPA potency on UF phenotype in vitro.

Methods:

We screened the antiproliferative effect of different (UPA/vitaminD3) combinations on UF cell proliferation using dimethylthiazolyl diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. Cells then were treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of vitamin D3 100 nM, and expression level of several markers related to proliferation, apoptosis, fibrosis, inflammation, and angiogenesis was measured on RNA or at protein level using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, Western blot, immunofluorescence, or multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay techniques.

Results:

Significant dose- and time-dependent growth inhibitory effects of UPA/vitamin D3 combinations were observed compared to untreated cells at 2 and 4 days (P < .05). Importantly, vitamin D3/UPA combination significantly reduced cell proliferation as compared to UPA at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days (P < .05). Combination treatment significantly decreased protein expression of proliferation markers Ki-67, PCNA, and CyclinD1 by more than 50% compared to UPA (P < .05) along with a significant increase in apoptosis induction. Combination treatment resulted in a 2-fold decrease in protein levels of extracellular matrix markers collagen-1 and fibronectin besides pro-fibrogenic cytokine transforming growth factor β3 (P < .05). Moreover, it significantly decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukins 6, 8, 1α, and 1β compared to UPA (P < .05).

Conclusion:

Combination of vitamin D3 with UPA exhibits additional and orchestrated anti-UF effects, therefore might offer a more favorable clinical option.

Keywords: uterine fibroids, ulipristal, vitamin D3, proliferation, African American

Background

Uterine fibroids (UFs, also known as leiomyoma or myoma) are the most common benign gynecologic tumors worldwide in women of reproductive age with a prevalence rate of 70% to 80% by the age of 50 years.1 Although these monoclonal neoplasms are benign, they are associated with significant clinical morbidity in 25% to 50% of affected women, ranging from heavy menstrual bleeding and pelvic pain to infertility, recurrent miscarriage, and preterm labor.2 Consequently, UFs have been estimated to account for an annual health-care cost up to US$34 billion. Thus, UFs represent a significant public health and financial burden.3

Since UFs are benign and cause morbidity, not mortality, besides its molecular pathogenesis is still unclear, there has been little advance in treatments of UFs; currently, the only cure for UFs is surgical intervention. Approximately 200 000 hysterectomies, 30 000 myomectomies, and thousands of uterine artery embolization and high-intensity-focused ultrasound procedures are performed annually in the United States.3 Nevertheless, many risks are involved with the surgical option choice plus the possibility of eradicating any hope of future pregnancies, making it a less favorable option for women. As of now, there is no pharmacological agent that is universally accepted and approved for long-term therapy of UFs.4 Accordingly, there is unmet need for appropriate therapeutic options for UFs ideally to be noninvasive, long term, effective, safe, cost-effective, and fertility friendly.5

A growing number of clinical and experimental studies support the key role of progesterone in UF growth and development. Therefore, selective progesterone receptor modulators are poised, pending additional clinical trials and safety evaluation, to provide additional option for UF management as an alternative to surgery.6 Ulipristal acetate (UPA), the leading compound of this family, has been approved in Europe and several countries worldwide and pending Food and Drug Administration approval in the United States as the first oral treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding in patients with UFs.2 The well-designed European randomized controlled multicenter phase III clinical trials (PEARLs) showed a superior efficacy of UPA on achieving amenorrhea and reducing both uterus and fibroid size as well as increasing quality of life.7 The first US-based phase III clinical trial (VENUS I) showed similar promising results in terms of rate of and time to amenorrhea in different racial groups as well as quality of life improvement.8

Both PGL4001 [Ulipristal Acetate] Efficacy Assessment in Reduction of Symptoms Due to Uterine Leiomyomata (PEARL I) and VENUS I studies showed that UPA, either 5 or 10 mg daily for 3 months, was superior to placebo; however, rate of responders for amenorrhea either by day 11 or during the last 35 consecutive days of treatment was lower in VENUS I as compared to PEARL I. Furthermore, fibroid size reduction, as compared to placebo, was significant in PEARL I while nonsignificant in VENUS I. One reason for this discrepancies might be the difference in patients characteristics as 69% of patients included in VENUS I were black, while there was no black patients included in PEARL I.8,9

Race is one of the main determinants of UFs’ incidence and severity.10 Uterine fibroids’ relative risk, incidence, and prevalence are greater (3- to 4-folds) among black women than white women in US population, also black women develop UFs 10 years earlier and have more and larger UFs than white women, so the severity of symptoms tends to be greater.1 The basis for this ethnic risk disparity is not fully understood, yet several recent studies implicate vitamin D deficiency as a major contributor11-13 since black women have 10-fold increased risk of vitamin D deficiency compared to white women, besides UF risk is inversely correlated with vitamin D serum levels.14

Our group and others have well characterized the role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) in UF management and demonstrated that VitD3 exhibited a potent antiproliferative, antifibrotic, and apoptotic effect both in vitro and in vivo.14 Uterine fibroid cells are characterized by high proliferation rate, impaired apoptosis, more abundance of disorganized extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, and recently improper inflammatory responses under influences of steroidal hormones estrogen and progesterone, growth factors, and cytokines.15 Given the existing data, the aim of this study is to investigate whether adding VitD3 can enhance the potency of UPA on human UF cells through examining combination effect, compared to UPA, on multiple key pathways related to UF development.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Cultures

The immortalized human UF cell line (HuLM) and immortalized human uterine smooth muscle (UTSM) cells were a generous gift from Dr Darlene Dixon (National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). These cells were cultured and maintained in smooth muscle cell culture medium (SmBM) with 5% fetal bovine serum, 0.1% insulin, 0.2% recombinant human fibroblast growth factor B, 0.1% gentamicin sulfate and amphotericin B mixture, and 0.1% human epidermal growth factor at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air; HuLM cells were passaged 2 times, and once they were 70% confluent, media was replaced by phenol red-free, serum-free Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM)/F-12 for different treatments. Absolute ethanol was used to dissolve the drugs. The final concentration of ethanol in culture media was <.01% and the same concentration of ethanol was used as vehicle in control cultures.

Reagents and Antibodies

Bioactive VitD3, UPA, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were purchased from Sigma Biochemicals (St Louis, Missouri). SmBM was purchased from Lonza (Walkersville, Maryland). DMEM/F-12 was purchased from Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts). Antibodies were purchased as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of Antibodies With Used Dilutions.

| Antibodies | Manufacturer and Catalog Number | Species Raised, Monoclonal or Polyclonal | Technique and Dilution Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-Ki-67 | Abcam, ab66155 | Rabbit, polyclonal | IF, 1:250 |

| Antiproliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7907 | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:750 |

| Anti-cyclinD1 | Cell Signaling technology, # 2978 | Rabbit, monoclonal | WB, 1:750 |

| Anti-caspase 3 | Cell Signaling technology, #9665 | Rabbit, monoclonal | WB, 1:1000 |

| Anti-cleaved caspase 3 | Abcam Biotechnology, ab32024 | Rabbit, monoclonal | WB, 1:500 |

| Anti-poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-7150 | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:1000 |

| Anti-bax | Abcam, ab32503 | Rabbit, monoclonal | WB, 1:2000 |

| Anti-collagen type I | Fitzgerald, 70R-CR007x | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:2000 |

| Anti-transforming growth factor beta 3 (TGF-β3) | Novus Biologicals, NB600-1531 | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:500 |

| Anti-fibronectin | Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-29578 | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:3000 |

| Anti-collagen type I | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-59772 | Mouse, monoclonal | IF, 1:100 |

| Anti-vitamin D receptor (VDR) | Abcam, ab134826 | Rabbit, polyclonal | WB, 1:1000 |

| Anti-beta actin | Sigma Biochemicals, A5316 | Mouse, monoclonal | WB, 1:5000 |

Abbreviations: IF, immunofluorescence, WB: Western blot.

Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were cultured in 10 cm tissue culture dishes, serum starved for overnight, and treated with either UPA 100 nM alone or in combination with VitD3 100 nM for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Cells were collected and lysed in lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), protein was quantified using Bradford method (Bio-Rad protein Assay kit), 30 µg of protein lysates was resolved in gradient (4%-20%) sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California), and incubated with specific primary antibodies overnight in dilutions as listed in Table 1, followed by 90 minutes of incubation with appropriate Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). Antigen–antibody complex was detected with pierce-enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) or Trident Femto western HRP substrate (GeneTex, Irvine, CA). Specific protein bands were visualized using ChemiDoc XRS + molecular imager (Bio-Rad). The intensity of each protein band was quantified by Bio-Rad Image Lab software and normalized against corresponding β-actin; normalized values were used to create data graphs.

Isolation of Cellular RNA From HuLM Cells and Complementary DNA Synthesis

The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were cultured in 10-cm tissue culture dishes, serum starved for overnight, and treated with either UPA 100 nM alone or in combination with VitD3 100 nM for 2 days. Cells were trypsinized and cell pellets were obtained by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 minutes. Total cellular RNA was isolated using Purelink RNA mini kit (Ambion, Life Technologies, Waltham, MA). The concentration of total RNA was determined using NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). One microgram of total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed in 20 µL reaction volume to complementary DNA (cDNA) using Ecodry premix double primed (Clontech Lab, Kusatsu, Japan). The reaction mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 42°C and stopped by incubation at 70°C for 10 minutes.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed to determine the messenger RNA (mRNA) expression of several genes listed with their primer sequences in Table 2. Primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa). An equal amount of cDNA from each sample was added to the Mastermix containing appropriate primer sets and SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad) in a 20 µL reaction volume. All samples were analyzed in triplicates. Real-time PCR analyses were performed using a Bio-Rad CFX connect. Cycling conditions including denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds and 60°C for 30 seconds, then 65°C for 5 seconds. Synthesis of a DNA product of the expected size was confirmed by melting curve analysis. Fold change and statistical analysis were calculated using Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1 software. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase values (internal control) were used to normalize the expression data, and normalized values were used to create data graphs.

Table 2.

Human Forward and Reverse Primers Sequences for qRT-PCR.

| Gene | Forward Primer Sequence | Reverse Primer Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | 5′-GTCAGCTCGTTACTCAACTC-3′ | 5′-GCTAGGCTTCCTGGTTTC-3′ |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | 5′-GCAAGTGGAGAACTTGGAAATG-3′ | 5′-GCCTAAGATCCTTCTTCATCCTC-3′ |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 | 5′-TTGTGGCCTTCTTTGAGTTCGGTG-3′ | 5′-GGTGCCGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCA-3′ |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase | 5′-AGGTCAAGGAGGAAGGTATCA-3′ | 5′-CAGAGTGTTCCAGTCCAGAATC-3′ |

| TGF-β3 | Transforming growth factor β 3 | 5′-CACACAGTCCGCTTCTTC-3′ | 5′-AGAAGAGGGTGGAAGCC-3′ |

| FMDN | Fibromodulin | 5′-TTTTATCATCGTTCTGCCTTCATG-3′ | 5′-TGTTTGCGGGACCTTAGGAA-3′ |

| BGN | Biglycan | 5′-TTGCCCCCAAACCTGTACTG-3′ | 5′-AAAACCGGTGTCTGGGACTCT-3′ |

| VSCN | Versican | 5′-TGGAATGATGTTCCCTGCAA-3′ | 5′-AAGGTCTTGGCATTTTCTACAACAG-3′ |

| FN | Fibronectin | 5′-AAACCAATTCTTGGAGCAGG-3′ | 5′-CCATAAAGGGCAACCAAGAG-3′ |

| COL1A | Collagen type I | 5′-GGCGACAGAGGCATAAAG-3′ | 5′-TCATCAGCCCGGTAGTAG-3′ |

| MMP 2 | Matrix metalloproteinase 2 | 5′-TCTACTCAGCCAGCACCCTGGA-3′ | 5′-TGCAGGTCCACGACGGCATCCA-3′ |

| MMP 9 | Matrix metalloproteinase 9 | 5′-TTCGACGTGAAGGCGCAGATGGT-3′ | 5′-TAGGTCACGTAGCCCACTTGGTC-3′ |

| TIMP 1 | Tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase 1 | 5′-TGGACTCTTGCACATCACTACCTGC-3′ | 5′-AGGCAAGGTGACGGGACTGGAA-3′ |

| NFKB1 | Nuclear factor kappa-B | 5′-CCCTGACCTTGCCTATTTG-3′ | 5′-GCTGTCCTGTCCATTCTTAC-3′ |

| RANKL | Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand | 5′-AGAAAGCGATGGTGGATGG-3′ | 5′-GGGATGTCGGTGGCATTA-3′ |

| IL-1 β | Interleukin 1 beta | 5′-ACAGATGAAGTGCTCCTTCCA-3′ | 5′-GTCGGAGATTCGTAGCTGGAT-3′ |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 | 5′-TGCAATAACCACCCCTGACC-3′ | 5′-GTGCCCATGCTACATTTGCC-3′ |

| IL-8 | Interleukin 8 | 5′-GACCACACTGCGCCAACAC-3′ | 5′-CTTCTCCACAACCCTCTGCAC-3′ |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α | 5′-CTGGGCAGGTCTACTTTGGG-3′ | 5′-CTGGAGGCCCCAGTTTGAAT-3′ |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor | 5′-AGCCCTGAAGTGGATAGAG-3′ | 5′-GCACCGGCAGACATAAC-3′ |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor | 5′-CGCAAGTGTAAGAAGTGCGAA-3′ | 5′-CGTAGCATTTATGGAGAGTGAGTCT-3′ |

| VEGF-A | Vascular endothelial growth factor | 5′-CTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT-3′ | 5′-GCAGTAGCTGCGCTGATAGA-3′ |

| ADM | Adrenomedullin | 5′-CGAAAGAAGTGGAATAAGTGGG-3′ | 5′-TCAAGTAATAGTGAGGCTTGCG-3′ |

| PDFG-A | Platelet-derived growth factor A | 5′-CACACCTCCTCGCTGTAGTATTTA-3′ | 5′-GTTATCGGTGTAAATGTCATCCAA-3′ |

| PDFG-B | Platelet-derived growth factor B | 5′-TCCCGAGGAGCTTTATGAGA-3′ | 5′-ACTGCACGTTGCGGTTGT-3′ |

| VDR | Vitamin D receptor | 5′- ATGCCATCTGCATCGTCTC-3′ | 5′-GCACCGCACAGGCTGTCCTA-3′ |

Abbreviation: qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction.

Immunofluorescence and Laser Confocal Microscopy

The 8 × 104 HuLM cells were cultured over sterile glass cover slips in 6-well plates, when reached 60% confluence, serum starved overnight and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol vehicle was added to the control cells. Cells were fixed in a 4% formaldehyde solution at room temperature for 15 minutes. After washing in Phosphate based saline (PBS) 3 times, cells were permeabilized for 15 minutes using 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS, and then nonspecific binding was inhibited by blocking for 1 hour in blocking/incubation solution containing 1% bovine serum albumin in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS. Incubation with either primary anti-Ki67 (1:250) or anti-collagen type 1 antibody (1:100) was performed for 2 hours, then incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 or anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher; 1:1000 each) for 1 hour, respectively, at room temperature. Cells were washed for 15 minutes (3 washes of 5 minutes each) with the above-described incubation solution, air-dried, and mounted onto microscopic slides with 1 drop of Fluoroshield (Sigma) containing 40,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole for nuclear staining. Fluorescent signals were visualized using Zeiss 780 upright laser confocal fluorescent microscopy and ZEN Black 2012 confocal software. Images were captured at ×10 and ×40 magnification using ×10 EC Plan-Neofluar (dry)—0.30 Numerical Aperture (NA) and ×40 Plan-Apo (oil)—1.4 NA lenses, respectively, and exported using Zen Blue 2012 software.

Multiplex Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

For baseline measurement, 3 × 105 HuLM or UTSM cells were seeded in 60-mm plates; when reached 70% confluence, culture media was changed with fresh media with or without LPS 1 µg/mL for 24 hours, then cell culture supernatants were collected, centrifuged for 1 minutes at 1000 rpm at 4°C to get rid of any cell debris, and stored in −80°C till measurement. For treatment measurement, 3 × 105 HuLM cells were cultured in 60-mm plates, when reached 70% confluence, serum starved and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days, ethanol vehicle was added to the control cells, and cell culture supernatants were collected, processed, and stored as previously mentioned for cytokines measurements under regular unstimulated culture condition; for treatment measurement under stimulated condition, fresh media was then added to cultured cells with LPS 1 µg/mL for 24 hours, and cell culture supernatants were collected, processed, and stored as previously mentioned for cytokines measurements under stimulated condition. At measurement time, supernatants were thawed and diluted using TCM sample diluent and concentrations of secreted cytokines interleukin (IL) 1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) were measured by multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using human Cytokine 5-Plex array assay kit (Aushon Biosystems, Billerica, Massachusetts); luminescence was captured by Cirascan Imaging system and analyzed using Cirasoft Analysis software (Aushon Biosystems).

Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation assay was performed by dimethylthiazolyl diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, 2000 HuLM cells were seeded in 96 well-plates and treated with different treatments for different time points as described in the figure legends. Ethanol vehicle was added to the control cells. One hundred microliters of 0.5 mg/mL MTT in PBS solution was added to each well and plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 hours, aspirated, and 150 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added to each well and agitated gently on shaker for 15 minutes while protected from light. Absorbance was measured in synergy HT multidetection microplate reader (BioTek, Broadview, Illinois) at 570 nm.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or standard error of the mean. Two-tailed unpaired Student t test was used to assess any statistical significant differences between any 2 compared groups of untreated control or different treatment groups. Values were considered statistically significant at 95% confidence interval level when P value <.05. GraphPad 7.0 (La Jolla, California) was used for generating the graphs.

Results

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Enhanced the Antiproliferative Effect of UPA on Human UF Cells

Effect of UPA/VitD3 combinations on HuLM cell viability

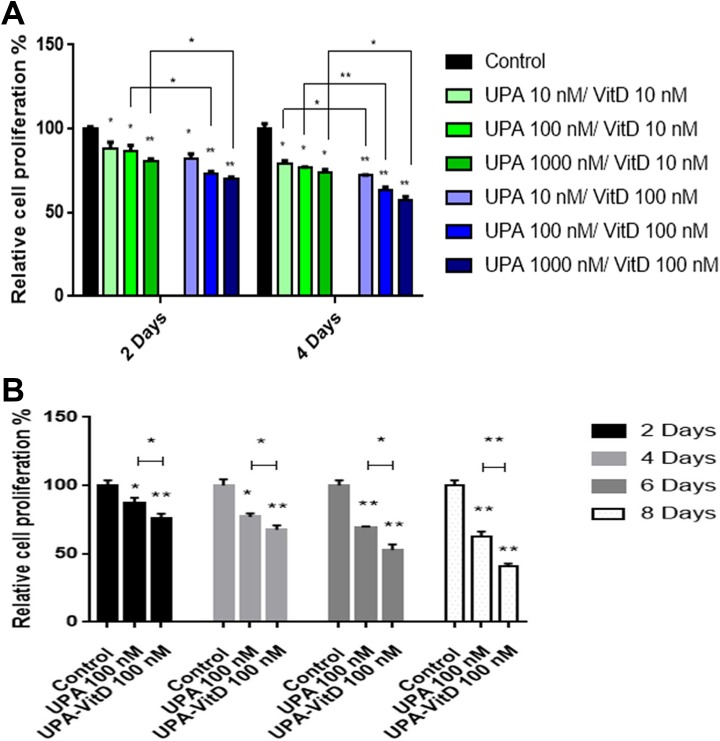

To evaluate whether VitD3 can enhance the antiproliferative effect of UPA on HuLM cell growth, HuLM cells were treated with graded concentrations of UPA (10-1000 nM) in the presence of either 10 or 100 nM VitD3 for 2 and 4 days, and cell growth and proliferation were determined using MTT assay and compared to untreated cultured cells (Figure 1A). Both concentration- and time-dependent growth inhibitory effect of UPA/VitD3 combination were observed. Unpaired Student t test showed a statistical significant reduction when compared to untreated cells (P < .05) for all used combination concentrations at the 2 time points. Interestingly, increasing VitD3 concentration while fixing UPA concentration statistically increased the HuLM growth inhibitory effect at both 2 and 4 days of treatment.

Figure 1.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA)/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatments on the proliferation of human UF cell line (HuLM) cells. The 2 × 103 HuLM cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with (A) graded concentration of UPA (10-1000 nM) in the presence of 10 or 100 nM VitD3 for 2 and 4 days. B, Ulipristal acetate (UPA) 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2, 4, 6, and 8 days. Cell proliferation was assessed in each time point using MTT assay. Individual data points are the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement (as percentage of untreated control). *P < .05, **P < .001. The experiments were repeated twice. Ethanol was used as vehicle control.

The UPA treatment alone has been shown previously to inhibit the cell proliferation in UF cells.16 To determine whether UPA/VitD3 combination treatment exhibits more inhibitory effect of UF cell proliferation than UPA treatment alone, HuLM cells were treated with 100 nM UPA in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2, 4, 6, and 8 days and cell viability was determined using MTT assay (Figure 1B). As expected, UPA treatment alone significantly decreased HuLM cell growth as compared to untreated cells at all time points (P < .05). Notably, UPA in combination with VitD3 treatment showed a further significant growth reduction as compared to UPA alone in a time-dependent manner (P < .05) at 2, 4, 6, and 8 days, respectively.

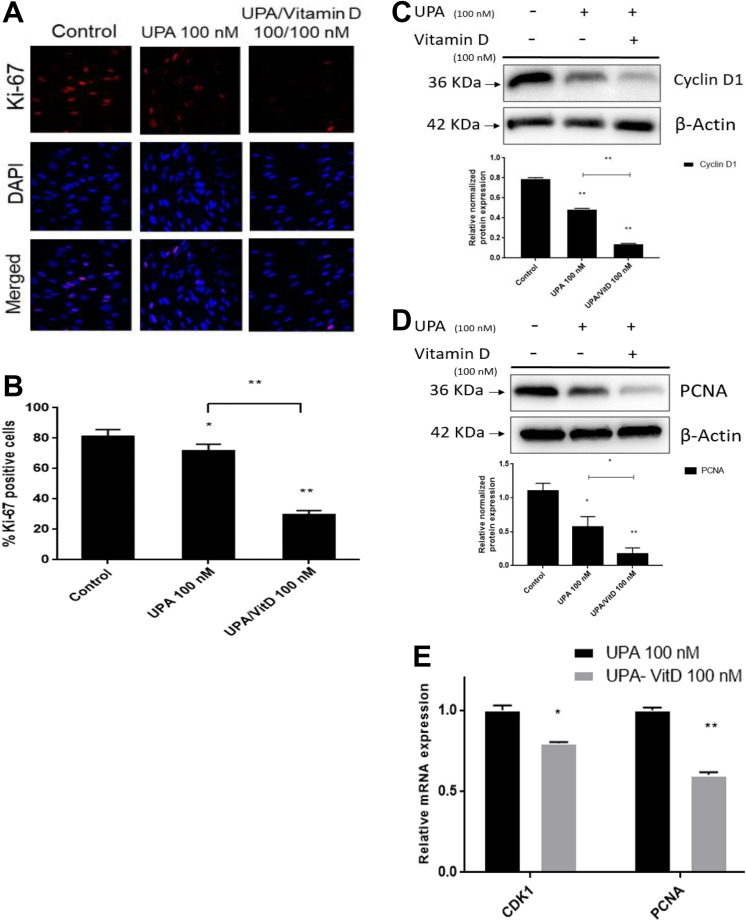

The effect of UPA/VitD3 combination treatment on the levels of proliferation-related markers in human UF cells

To further confirm the previous finding that addition of VitD3 treatment will increase the antiproliferative effect of UPA, the HuLM cells were treated with UPA 100 nM in the absence or presence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. The positive cells for proliferation marker Ki-67 were counted using immunocytochemistry staining and confocal laser microscopy (Figure 2A and B). Combination treatment significantly reduced the number of Ki-67-positive cells as compared to cells treated with UPA alone and untreated cells (P < .001). Western blot analysis demonstrated that UPA (100 nM) treatment alone reduced Cyclin D1 expression by 40% as compared to untreated cells, adding VitD3 showed additional reduction in Cyclin D1 expression by about 43% as compared to UPA alone and about 80% as compared to untreated cells (P <.001; Figure 2C). Furthermore, UPA decreased expression of PCNA by almost 50% as compared to untreated cells (P < .05). Ulipristal acetate treatment in combination with VitD3 showed further reduction in PCNA expression by 85% as compared to untreated cells (P < .001) and by 35% as compared to cells treated with UPA alone (P < .05; Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA)/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on the proliferation marker level in human uterine fibroid (UF) cells. A and B, The effect of UPA versus UPA/VitD3 combination treatment on Ki-67 expression in human UF cell line (HuLM) cells: 8 × 104 HuLM cells were seeded over sterile glass cover slip in 6-well plates and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ki-67 expression was assessed using immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser microscopy (×40). Individual data points are the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of ki-67 positive nuclei of 300 to 500 cells from 4 different fields ×10 (as percentage of the number of nuclei). C and D, The effect of UPA versus UPA/VitD3 combination treatments on Cyclin D1 and PCNA protein levels in HuLM cells: 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight and treated with 100 nM UPA in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Western blot analysis was performed using anti-CyclinD1 and PCNA antibodies. The intensity of each signal was quantified and normalized to the corresponding β-actin and presented in the graph as mean ± SD. E, The messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of PCNA and CDK1 genes were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) using gene-specific primers as described in Materials and Methods. The mRNA levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data were presented as mean ± SEM of triplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001. The experiments were repeated twice. Ethanol was used as vehicle control.

To determine whether the downregulation of cell proliferation-related proteins is accompanied by decreased gene transcriptional activity, the mRNA expression levels of cell proliferation-related genes were measured in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with VitD3 (100 nM) for 2 days. Combination treatment significantly reduced mRNA expression of CDK1 and PCNA by 1.26-fold and 1.66-fold, respectively, compared to UPA alone (P < .05; Figure 2E).

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Enhances the Apoptotic Effect of UPA on Human UF Cells

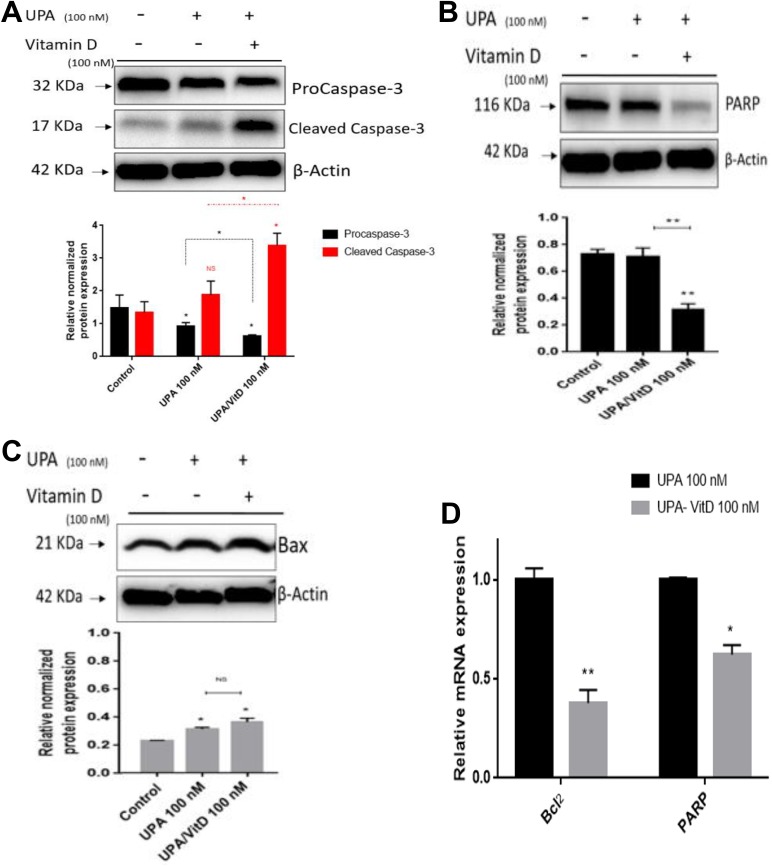

To evaluate whether adding VitD3 will increase the apoptotic effect of UPA, the HuLM cells were treated with UPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of VitD3 (100 nM) for 2 days and expression levels of key markers for apoptosis including procaspase-3, active caspase-3, total Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), and Bax were measured by Western blot analysis. Compared to untreated cells, UPA alone significantly decreased procaspase-3 protein levels by 38% (P < .05), which was further decreased (60%) significantly by adding VitD3 (P < .05). In addition, an increase (1.4 fold) in cleaved caspase-3 expression was observed with UPA alone, while adding VitD3 significantly increases cleaved caspase-3 expression by 3-folds (P < .05; Figure 3A). Caspase-3 is a critical executioner of apoptosis as it cleaves many proteins such as PARP which is implicated in apoptosis as cleavage of PARP is regarded as a hallmark event for apoptosis paradigm. In this regard, we determined whether UPA/VitD3 combination exhibited more decrease in PARP expression as compared to either untreated cells or cells treated with UPA alone. Our study showed that UPA/VitD3 combination treatment significantly decreased PARP expression levels as compared to untreated group or UPA alone (P < .001; Figure 3B). Similar finding was observed when measuring the protein expression levels of pro-apoptotic marker Bax. Ulipristal acetate significantly increased Bax expression as compared to untreated control (P < .05) Adding VitD3 showed further increase in Bax protein expression as compared to UPA alone; however, combination treatment did not reach significance (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA)/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatments on apoptosis of human UF cell line (HuLM) cells. The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with 100 nM UPA in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Western blot analysis was performed using (A) anti-procaspase-3, -Cleaved caspase-3, (B) PARP, and (C) Bax antibodies, the intensity of each protein signal was quantified and normalized to the corresponding β-actin and presented in the graph as mean ± standard deviation (SD). D, The messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of BCL2 and PARP genes were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific sense and antisense primers as described in Materials and Methods. The mRNA levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001. The experiments were repeated twice.

To determine whether transcriptional levels of antiapoptotic genes differ between combination and UPA alone, we measured the mRNA expression levels of antiapoptotic BCL2 and PARP genes in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with VitD3 (100 nM) for 2 days. Adding VitD3 significantly reduced gene expression of BCL2 and PARP by 2.64- and 1.6-fold, respectively, as compared to UPA alone (P < .05; Figure 3D).

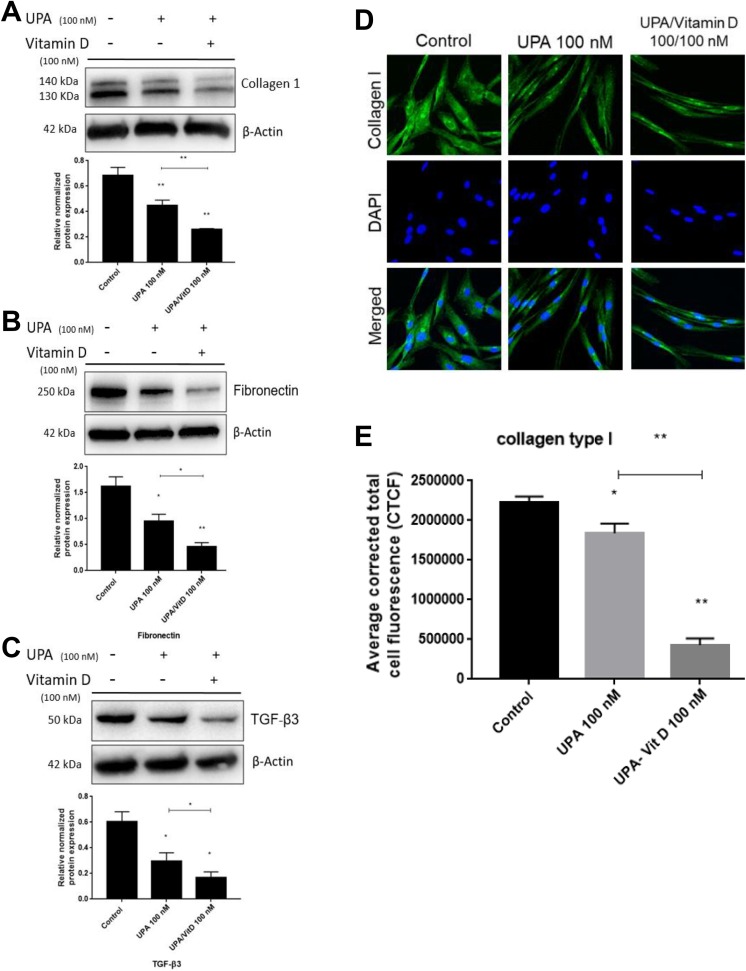

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Enhanced the Antifibrotic Effect of UPA on Human UF Cells

To evaluate whether adding VitD3 will enhance the antifibrotic effect of UPA, HuLM cells were treated with UPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of VitD3 100 nM for 2 days. The protein levels of ECM-associated markers including collagen type I (COL1A) and fibronectin (FN1) as well as the pro-fibrogenic cytokine transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3) were measured by Western blot analysis. Compared to untreated cells, UPA significantly decreased COL1A expression by 35% (P < .001), which was further decreased (37%) significantly by adding VitD3 (P < .001; Figure 4A). Similar findings were observed regarding FN1 and TGF-β3 protein expression in response to combination treatment. The UPA alone showed marked reduction in FN1 and TGF-β3 by about 50% and 40%, respectively, relative to untreated cells (P < .05), which were further significantly decreased by adding VitD3 to reach almost 28% for both markers (P < .05-.001; Figure 4B and C). To confirm the decreased expression of COL1A, HuLM cells were treated with UPA 100 nM in the absence or presence of VitD3 100 nM for 2 days. Pattern of COL1A fibers was observed and quantified using immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy imaging. The immunofluorescence data revealed significant reduction in intense and disorganized collagen fibers either with UPA alone or UPA/VitD3 combination by 20% (P < .05) and 80% (P < .001), respectively (Figure 4D and E). Notably, UPA/VitD3 combination treatment exhibited more decrease in collagen fibers intensity as compared to UPA alone (P < .001).

Figure 4.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA)/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on fibrosis-related proteins of human UF cell line (HuLM). The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Western blot analysis was performed using anti- (A) collagen type I (B) fibronectin, and (C) transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3) antibodies. The intensity of each protein signal was quantified and normalized to the corresponding β-actin and presented in the graph as mean ± standard deviation (SD). D and E, The 8 ×104 HuLM cells were cultured over sterile glass cover slip in 6-well plates, serum starved, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. Collagen type I expression was assessed using immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser microscopy (×40 imaging). Individual data points are the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of corrected total cell fluorescence of 150 cells from 9 different fields ×40 quantified using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software. *P < .05, **P < .001. The experiments were repeated twice.

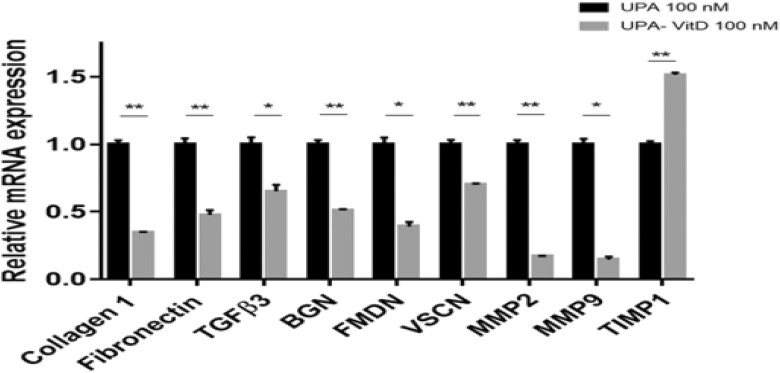

To determine whether UPA and VitD3 combination treatment further decreases the mRNA expression of proteoglycans and ECM-associated gene as compared to UPA alone, we performed qRT-PCR analysis in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with VitD3 100 nM for 2 days. The mRNA expression levels of fibrosis-related genes (COL1A, FN1, and TGF-β3), proteoglycans-related genes (fibromodulin [FMDN], biglycan [BGN], and versican [VSCN]), and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) genes (MMP2 and MMP-9) were significantly downregulated in HuLM cells treated with combination as compared with UPA alone. On the other hand, the mRNA expression levels of tissue inhibitor of MMP 1 (TIMP1) were significantly increased in combination with treated HuLM cells as compared to UPA treated alone (P < .05-.001; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA)/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on fibrosis-related genes of human UF cell line (HuLM). The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of gene coding for collagen type I, fibronectin, transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3), biglycan (BGN), fibromodulin (FMDN), versican (VSCN), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2, MMP9, and tissue inhibitor of MMP 1 (TIMP1) were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific sense and antisense primers as described in Materials and Methods. The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001. The experiments were repeated twice.

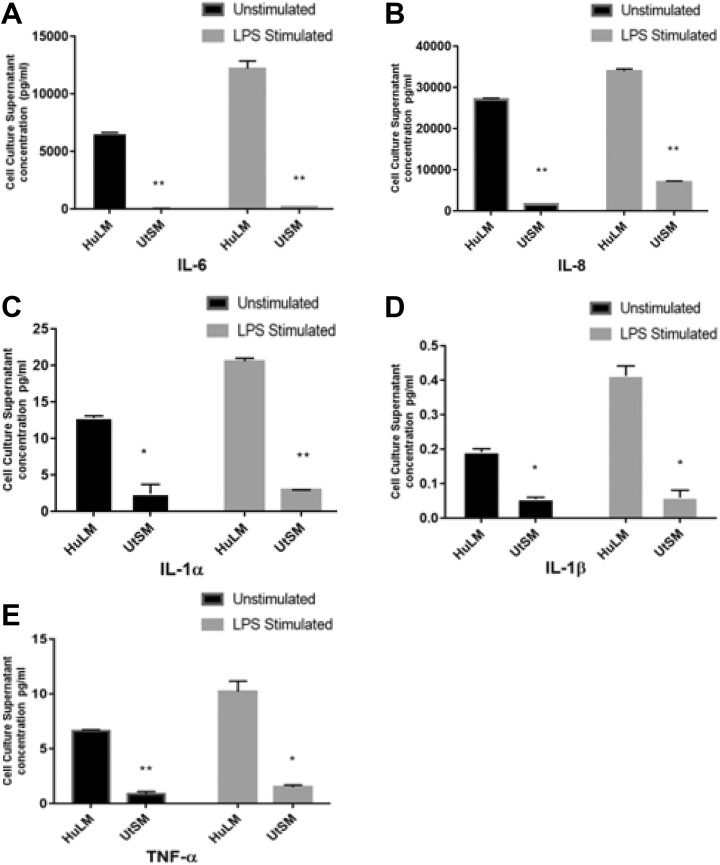

Human UF Cells Produced Higher Amounts of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Than UTSM Cells

To examine whether there is differential secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines from HuLM and UTSM cells, cell culture supernatants from both cell lines were collected. In addition, supernatants from both HuLM and UTSM cells treated with inflammation inducer LPS (1 µg/mL, 24 hours) were also collected. The production of ILs IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were measured by multiplex ELISA using human Cytokine 5-Plex array assay kit. The HuLM cells secreted remarkably higher amounts of all measured secreted cytokines as compared to UTSM under both stimulated (LPS) and unstimulated condition (P < .05-.001; Figure 6A-E).

Figure 6.

The secretion of inflammatory cytokines from human UF cell line (HuLM) and uterine smooth muscle (UTSM) cells under stimulated and unstimulated conditions. The 3 × 105 HuLM or UTSM cells were seeded in 60-mm plates. When cells were reached 70% confluence, culture media was changed with fresh one with or without lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 1 µg/mL for 24 hours, then cell culture supernatants were collected. The concentrations of interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α (A-E) in the collected media were measured by multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using human cytokine 5-Plex array assay kit. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of duplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001.

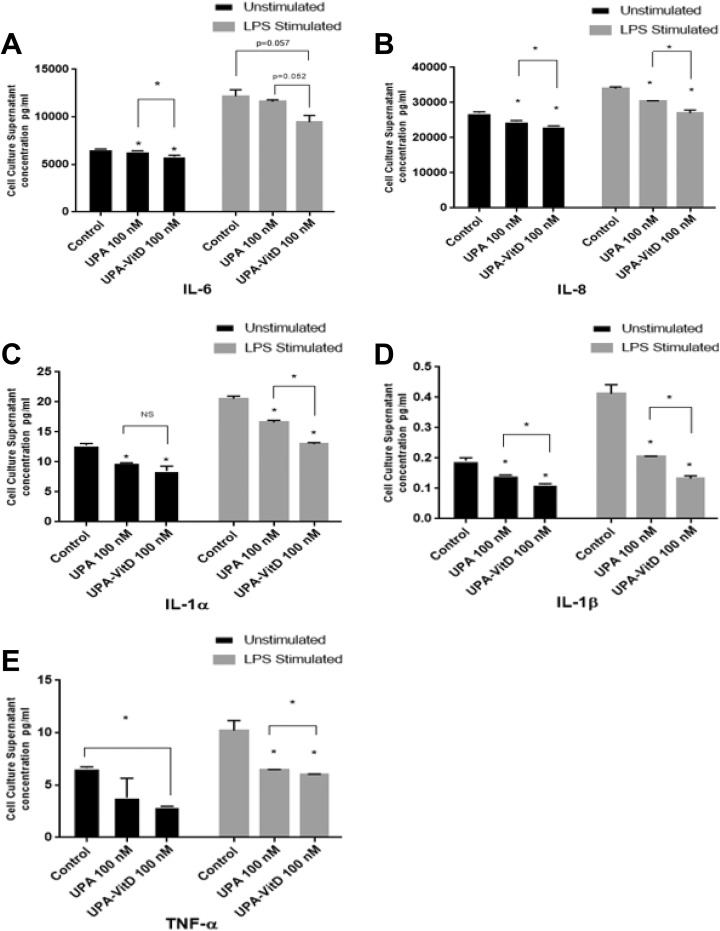

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Increased the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of UPA on Human UF Cells

To assess whether UPA can reduce the abnormally high secretory profile of inflammation mediating cytokines from HuLM cells and whether this antiinflammatory effect can be further enhanced by adding VitD3, HuLM cells were treated with UPA (100 nM) in the presence or absence of 100 VitD3 for 2 days. Cell culture supernatants were then collected for unstimulated condition measurements. For stimulated condition, fresh media with LPS 1µg/mL was used for further 24 hours growth and cell culture supernatants were then collected for stimulated condition measurements. Concentrations of IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α were measured by multiplex ELISA using human Cytokine 5-Plex array assay kit. The UPA treatment showed a novel anti-inflammatory effect as demonstrated by significantly reducing secretion of cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-8 as compared to untreated cells (P < .05) either under unstimulated normal condition or stimulated condition induced by LPS, except for TNF-α under unstimulated condition and IL-6 under LPS stimulated condition where reductions did not reach a statistical significance. Furthermore, combination treatment improved the anti-inflammatory effect of UPA and caused further significant reduction in all secreted measured cytokines as compared to UPA alone (P < .05) either under unstimulated normal condition or stimulated condition induced by LPS (except for IL-1α and TNF- α under unstimulated condition, and IL-6 under LPS stimulated condition where reductions did not reach a significance; Figure 7A-E).

Figure 7.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA) versus UPA/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on inflammatory cytokines production in human UF cell line (HuLM). The 3 × 105 HuLM cells were cultured in 60-mm plates, serum starved, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days; ethanol was used as vehicle control. Cell culture supernatants were collected for unstimulated condition measurements and fresh media is added with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 1 µg/mL for 24 hours, then cell culture supernatants were collected for stimulated condition measurements, concentrations of interleukin (IL) 6, IL-8, IL-1α, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α (A-E) were measured by multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using human Cytokine 5-Plex array assay kit. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of duplicate measurement. *P < .05, NS, nonsignificant.

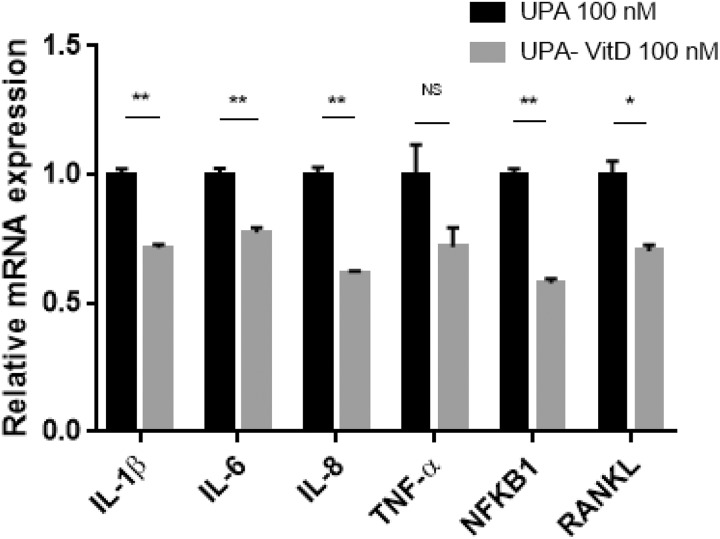

To determine whether combination treatment decreases the production of pro-inflammatory mediators via downregulation of their transcriptional activity, we measured mRNA expression levels of genes including IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, nuclear factor kappa-B (NFKB1) and receptor activator of NFKB1 ligand (RANKL) in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with vitD3 (100 nM) for 2 days. Adding VitD3 to UPA significantly decreased gene expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, NFKB1, and RANKL (P < .05-.001), while reduction did not reach a significance for TNF-α (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA) versus UPA/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on inflammation-related genes in human UF cell line (HuLM). The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of genes coding for interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, nuclear factor kappa-B (NFKB1), and receptor activator of NFKB1 ligand (RANKL) genes were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific sense and antisense primers as described in Materials and Methods. The mRNA levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001, NS, nonsignificant. The experiment was repeated twice.

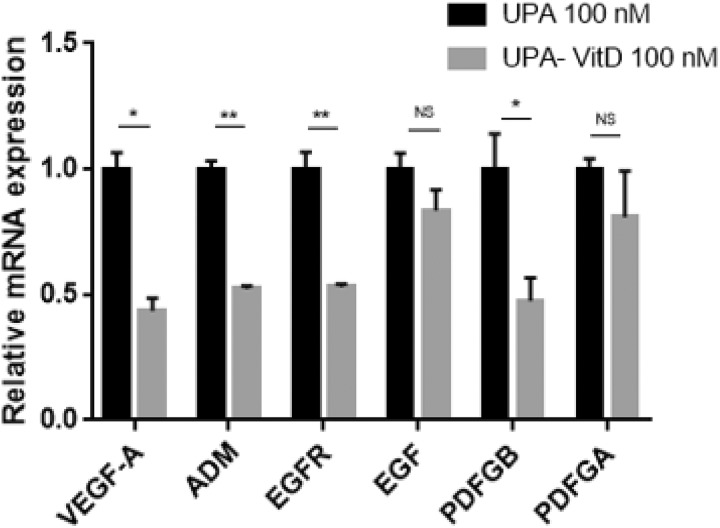

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Increased the Antiangiogenic Effect of UPA on Cultured Human UF Cells

To explore whether VitD3 can enhance the antiangiogenic effect of UPA, we measured mRNA expression levels of angiogenesis-related genes including vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), adrenomedullin (ADM), epidermal growth factor (EGF), EGF receptor (EGFR), platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF)-A, and PDGF-B in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with VitD3 100 (nM) for 2 days. Adding VitD3 significantly reduced gene expression of VEGF-A, ADM, EGFR, and PDGF-B (P < .05-.001), while reduction in EGF and PDGF-A was not statistically significant as compared to UPA treatment alone (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA) versus UPA/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on angiogenesis-related genes in human UF cell line (HuLM) cells. The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of genes coding for vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), adrenomedullin (ADM), epidermal growth factor (EGF), EGF receptor (EGFR), platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF)-A and PDGF-B genes were measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific sense and antisense primers as described in Materials and Methods. The messenger RNA (mRNA) levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement. *P < .05, **P < .001, NS, nonsignificant. The experiments were repeated twice.

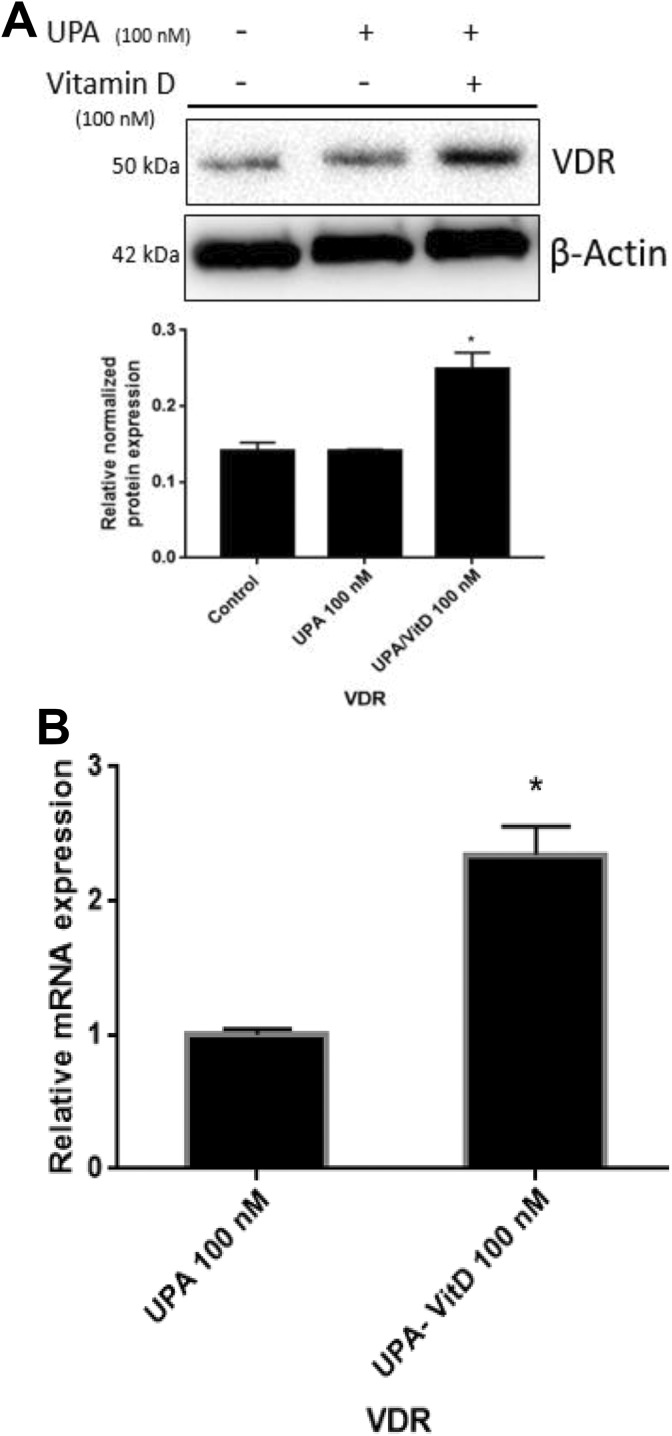

1,25 Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Increased Vitamin D Receptor Protein and Gene Expression on Human UF Cells

To determine whether VitD3 exerts its effects via induction of vitamin D receptor (VDR), protein and gene expression levels of VDR were analyzed using Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses, respectively, in HuLM cells treated with either UPA (100 nM) alone or in combination with VitD3 (100 nM) for 2 days. Combination of VitD3 with UPA significantly increased VDR expression as compared to UPA alone (P < .05; Figures 10A and 10B).

Figure 10.

The effect of ulipristal acetate (UPA) versus UPA/1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (VitD3) combination treatment on vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression in human UF cell line (HuLM). The 5 × 105 HuLM cells were seeded in 10-cm plates, serum starved overnight, and treated with UPA 100 nM in the presence or absence of 100 nM VitD3 for 2 days. Ethanol was used as vehicle control. A, Western blot analysis was performed using anti-VDR antibody. The intensity of each protein signal was quantified and normalized to the corresponding β-actin and presented in the graph as mean ± standard deviation (SD). B, The messenger RNA (mRNA) level of gene coding for VDR was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis using gene-specific sense and antisense primers as described in Materials and Methods. The mRNA levels were normalized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and normalized values used to generate the graph. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of triplicate measurement. *P < .05. The experiments were repeated twice.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that UPA exhibited an inhibitory effect on UF cell growth in both a concentration-dependent and time-dependent manner, which is consistent with previous finding.16-19 Moreover, adding VitD3 showed further significant decrease in UF cell viability in a dose- and time-dependent fashion as well. Uterine fibroids are composed of cells with aberrant proliferation and elevated expression of genes with antiapoptotic, pro-fibrotic, and pro-inflammatory activities, which play a central role in their growth and consequently associated symptoms.15,20,21 PCNA and Ki-67 are cell proliferation markers involved in cell growth, proliferation, and tumorigenesis, while Cyclin D1 and CDK1 are required for cell cycle G1-S and G2-M transitions, respectively. Their expression levels are higher in UFs compared to normal myometrium.22 Our group has previously demonstrated the antiproliferative effect of VitD3 on HuLM cells.14,23 In this regard, we would like to test whether combination shows enhanced effect compared to UPA treatment alone. Previous study showed that UPA decreased PCNA protein expression in HuLM cells,19 in addition to other study from our group demonstrated the capability of VitD3 to reduce PCNA, CDK1, Cyclin D1, and Ki-67 in either UF tissue of Eker rat model or cultured HuLM cells.23,24 Current results demonstrated that adding VitD3 to UPA lowered the protein expression of PCNA, Ki-67, and Cyclin D1 as well as PCNA and CDK1 gene expression as compared to either untreated or treated cells with UPA alone.

Uterine fibroid growth is in part due to imbalance between proliferation and apoptosis with excessive proliferation and several apoptotic pathways impairment. Compared to normal myometrium, UFs are accompanied by excessive accumulation of antiapoptotic proteins as BCL2 and fall in caspase activation cascade.25,26 Individual treatment of UPA or VitD3 previously induced apoptosis in cultured HuLM cells, and UPA was shown to increase the expression of cleaved caspase3 and cleavage of PARP while decreasing BCL2 expression.19 Our group has demonstrated similar findings with VitD3 with a decrease in BCL2, while an increase in cleaved caspase 3 expression both in vitro and in vivo.14 Present study confirmed these findings besides revealing that combination treatment augmented apoptosis stimuli as shown by more increase in cleavage of procaspase 3 to active caspase 3, which in turn induces more proteolytic cleavage and depletion of PARP. Cleavage of PARP is a hallmark event for apoptosis paradigm. Additionally, our combination treatment showed a further decrease in mRNA level of BCL2 and PARP compared to UPA alone, repression of antiapoptotic BCL2 increases the release of apoptotic proteins from mitochondria such as Bax protein, and the current study showed that Bax protein expression was increased in response to combination treatment relative to UPA alone or untreated cells.

Extracellular matrix accumulation is a distinguishing characteristic of UFs; ECM constructs UF’s rigid structure and thus contributes to the bleeding and pelvic pain. Moreover, ECM can stimulate downstream proliferation mediators in a process called mechanotransduction.15 Thus, appropriate anti-UF treatment should inhibit further accumulation of ECM-associated proteins including collagens, FN1, proteoglycans, MMPs, and their TIMPs.15 Various studies including microarray analysis reported overexpression of both mRNA and protein level of COLIA27-29 and FN130 in UF tissue and cells compared to myometrium. The UPA was reported to decrease their protein expression in HuLM cells31,32 and in UF tissues collected from patients treated preoperatively with UPA.33,34 Our group demonstrated previously the efficacy of VitD3 in suppressing the expression of same proteins in HuLM cells either under regular culture condition35 or induced by TGF-β336 as well as in animal model.24 Current study showed potent effect of combination treatment with significant reduction in expression of COLIA and FN1 at mRNA and protein level as well as TGF-β3 expression level. Transforming growth factor-β3 is fibrogenic cytokine which is known to be overexpressed in UFs37; this cytokine was shown to increase the expression of COLIA and FN136,38 as well as proteoglycans like versican.37 Proteoglycans, including versican, biglycan, and fibromodulin, are glycosylated proteins that play role in cell adhesion, migration, and proliferation besides tissue inflammation. Several studies presented their overexpression in UF tissues compared to myometrium.15 Ulipristal acetate and VitD3 were shown to individually reduce their protein and gene expressions in UF tissue or cells.33,35 Combination treatment showed additional decline in versican, biglycan, and fibromodulin gene expression compared to UPA alone.

Extracellular matrix remodeling process is regulated by balanced action of MMPs and TIMPs. Unbalanced expression and activities are thought to play a role in UF pathogenesis. Several MMPs, particularly MMP2 and MMP9, were found to be overexpressed in UFs compared to myometrium39,40 as well as in patients’ peripheral blood; these MMP elevation enables the proteolytic release of different ECM trapped growth and angiogenic factors and increase fibrosis process accordingly.41,42 Combination treatment decreased the gene expression of MMP2 and MMP9 while increased TIMP1; these data confirmed our previous finding of MMP2 and MMP9 reduction in HuLM cells in response to VitD3.42 Recent study showed that UPA decreased MMP9 while increased MMP2 expression; however, sample numbers were small to get a conclusion.33 Matrix metalloproteinase 9 is known to activate TGF-β3 and increases ECM production accordingly.43 Tissue inhibitor of MMP1 is a known inhibitor of MMP9 activity,43 so inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis.44 Our study showed that adding VitD3 to UPA increased gene expression of TIMP1 as compared to UPA alone.

Numerous studies highlighted the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in tumorigenesis via effects on cell growth, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling.45 Inflammation recently was shown to be involved in UF pathogenesis46 as well as ECM accumulation as fibrosis might occur due to imbalances in wound healing and repair processes during chronic tissue inflammation.47 Tumor necrosis factor α was found to be overexpressed in UFs45 which caused upregulation of MMP248 and activin-A which in turn increase ECM accumulation.49 Our group previously showed the possible role of TNF-α in HuLM cell proliferation.50 This study further demonstrated the aberrant secretion of cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1 α, and IL-1β from HuLM cells compared to normal myometrium cells both under unstimulated condition and LPS stimulated condition as we weren’t sure whether secreted cytokines will be within ELISA machine detection limit. Lipopolysaccharide was used previously by our group to show the anti-inflammatory effect of VitD3 in LPS-stimulated myometrial cells51 as well as others.52,53 Ulipristal acetate was shown previously to reduce cytokines expression in UFs.54 The present study results confirmed previous findings. In addition, combination treatment caused further reduction in such inflammatory response in UFs, as it decreased both secreted proteins and gene expression of aforementioned cytokines. In addition, combination treatment decreased the mRNA expressions of NF-KB1 and RANKL which are overexpressed in UFs45 and induced by progesterone in UF cells,55 respectively.

Traditionally, UFs were known to have reduced vascularization; however, recent accumulating evidences showed an abnormal UF vasculature with differential and higher expression of angiogenic growth factors compared to normal myometrium including PDGF, VEGF-A, ADM, and EGF.16,56 In addition, previous study showed that UPA attenuated VEGF- and ADM-mediated angiogenesis in HuLM cells, but not myometrial cells.57 Our study demonstrated that UPA/VitD3 combination caused further reduction in mRNA expression of VEGF-A, ADM, PDGF-B, and EGFR compared to UPA alone. These results are consistent with the previous findings, showing antiangiogenic effects of vitD3 in both in vitro and in vivo tumor models.58,59

Conclusion

In conclusion, we demonstrated for the first time that VitD3 significantly enhanced the anti-UF phenotype treatment of UPA. The combination of VitD3 and UPA exhibited orchestrated and multiple anti-UF effects. The combination treatment showed more inhibitory effect of UF cell growth and phenotype, along with lowering the expression levels of proliferation and ECM-associated markers as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines and angiogenic factors while inducing more apoptosis. This combination treatment might have favorable clinical utility especially in women of color who frequently have vitamin D deficiency. As VitD3, unlike UPA, can be used in continuous not cyclic fashion, it might inhibit potential fibroid regrowth in the UPA-free intervals in long-term UPA treatment protocols. Yet, clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Ayman Al-Hendy conceived the studies. Mohamed Ali and Ayman Al-Hendy designed experiments. Mohamed Ali performed all the experiments. Ayman Al-Hendy provided study materials. Ayman Al-Hendy and Nagwa Ali Sabri provided the financial support. Mohamed Ali, Nagwa Ali Sabri, Sara Mahmoud Shahin, and Qiwei Yang analyzed the data. Mohamed Ali wrote the manuscript. Qiwei Yang revised the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ayman Al-Hendy is a consultant for Allergan, Bayer, Repros, and Myovant Sciences, as well as AbbVie.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant R01 ES028615 (AA) and Egyptian governmental fund.

References

- 1. Stewart EA, Laughlin-Tommaso SK, Catherino WH, Lalitkumar S, Gupta D, Vollenhoven B. Uterine fibroids. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ali M, Al-Hendy A. Selective progesterone receptor modulators for fertility preservation in women with symptomatic uterine fibroids. Biol Reprod. 2017;97(3):337–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of uterine leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211 e211–e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ali M, Chaudhry ZT, Al-Hendy A. Successes and failures of uterine leiomyoma drug discovery. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2018;13(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Hendy A, Myers ER, Stewart E. Uterine fibroids: burden and unmet medical need. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(6):473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murji A, Whitaker L, Chow TL, Sobel ML. Selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) for uterine fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD010770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Donnez J, Donnez O, Matule D, et al. Long-term medical management of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(1):165–173 e164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simon JA, Catherino W, Segars JH, et al. Ulipristal acetate for treatment of symptomatic uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(3):431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Donnez J, Tatarchuk TF, Bouchard P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus placebo for fibroid treatment before surgery. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG. 2017;124(10):1501–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oskovi Kaplan ZA, Tasci Y, Topcu HO, Erkaya S. 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels in premenopausal Turkish women with uterine leiomyoma. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2018;34(3):261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paffoni A, Somigliana E, Vigano P, et al. Vitamin D status in women with uterine leiomyomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(8):E1374–E378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ciavattini A, Delli Carpini G, Serri M, et al. Hypovitaminosis D and “small burden” uterine fibroids: opportunity for a vitamin D supplementation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(52):e5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brakta S, Diamond JS, Al-Hendy A, Diamond MP, Halder SK. Role of vitamin D in uterine fibroid biology. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(3):698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Islam MS, Ciavattini A, Petraglia F, Castellucci M, Ciarmela P. Extracellular matrix in uterine leiomyoma pathogenesis: a potential target for future therapeutics. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(1):59–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoshida S, Ohara N, Xu Q, et al. Cell-type specific actions of progesterone receptor modulators in the regulation of uterine leiomyoma growth. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(3):260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baird DD, Hill MC, Schectman JM, Hollis BW. Vitamin d and the risk of uterine fibroids. Epidemiology. 2013;24(3):447–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roshdy E, Rajaratnam V, Maitra S, Sabry M, Allah AS, Al-Hendy A. Treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids with green tea extract: a pilot randomized controlled clinical study. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:477–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xu Q, Takekida S, Ohara N, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 down-regulates proliferative cell nuclear antigen and Bcl-2 protein expression and up-regulates caspase-3 and poly(adenosine 5’-diphosphate-ribose) polymerase expression in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chegini N. Proinflammatory and profibrotic mediators: principal effectors of leiomyoma development as a fibrotic disorder. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(3):180–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walker CL, Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids: the elephant in the room. Science. 2005;308(5728):1589–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dixon D, Flake GP, Moore AB, et al. Cell proliferation and apoptosis in human uterine leiomyomas and myometria. Virchows Arch. 2002;441(1):53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharan C, Halder SK, Thota C, Jaleel T, Nair S, Al-Hendy A. Vitamin D inhibits proliferation of human uterine leiomyoma cells via catechol-O-methyltransferase. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1):247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Halder SK, Sharan C, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment shrinks uterine leiomyoma tumors in the Eker rat model. Biol Reprod. 2012;86(4):116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Csatlos E, Mate S, Laky M, Rigo J, Jr, Joo JG. Role of apoptosis in the development of uterine leiomyoma: analysis of expression patterns of bcl-2 and bax in human leiomyoma tissue with clinical correlations. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2015;34(4):334–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang SC, Tang MJ, Hsu KF, Cheng YM, Chou CY. Fas and its ligand, caspases, and bcl-2 expression in gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist-treated uterine leiomyoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(10):4580–4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iwahashi M, Muragaki Y. Increased type I and V collagen expression in uterine leiomyomas during the menstrual cycle. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(6):2137–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stewart EA, Friedman AJ, Peck K, Nowak RA. Relative overexpression of collagen type I and collagen type III messenger ribonucleic acids by uterine leiomyomas during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(3):900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malik M, Norian J, McCarthy-Keith D, Britten J, Catherino WH. Why leiomyomas are called fibroids: the central role of extracellular matrix in symptomatic women. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(3):169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arici A, Sozen I. Transforming growth factor-beta3 is expressed at high levels in leiomyoma where it stimulates fibronectin expression and cell proliferation. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(5):1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Xu Q, Ohara N, Liu J, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 induces extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14(3):181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lewis TD, Malik M, Britten JL, Catherino WH. Ulipristal acetate decreases leiomyoma extracellular matrix through upregulation of nuclear receptor subfamily 4 members. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):e204. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cox J, Malik M, Britten J, Lewis T, Catherino WH. Ulipristal acetate and extracellular matrix production in human leiomyomas in vivo: a laboratory analysis of a randomized placebo controlled trial. Reprod Sci. 2018;25(2):198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Courtoy GE, Donnez J, Marbaix E, Dolmans MM. In vivo mechanisms of uterine myoma volume reduction with ulipristal acetate treatment. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(2):426–434 e421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Halder SK, Osteen KG, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d3 reduces extracellular matrix-associated protein expression in human uterine fibroid cells. Biol Reprod. 2013;89(6):150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Halder SK, Goodwin JS, Al-Hendy A. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces TGF-beta3-induced fibrosis-related gene expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):E754–E762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Norian JM, Malik M, Parker CY, et al. Transforming growth factor beta3 regulates the versican variants in the extracellular matrix-rich uterine leiomyomas. Reprod Sci. 2009;16(12):1153–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Joseph DS, Malik M, Nurudeen S, Catherino WH. Myometrial cells undergo fibrotic transformation under the influence of transforming growth factor beta-3. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(5):1500–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wolanska M, Sobolewski K, Bankowski E, Jaworski S. Matrix metalloproteinases of human leiomyoma in various stages of tumor growth. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2004;58(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tsigkou A, Reis FM, Ciarmela P, et al. Expression levels of myostatin and matrix metalloproteinase 14 mRNAs in uterine leiomyoma are correlated with dysmenorrhea. Reprod Sci. 2015;22(12):1597–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rodriguez D, Morrison CJ, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinases: what do they not do? New substrates and biological roles identified by murine models and proteomics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(1):39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Halder SK, Osteen KG, Al-Hendy A. Vitamin D3 inhibits expression and activities of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 in human uterine fibroid cells. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(9):2407–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dayer C, Stamenkovic I. Recruitment of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) to the fibroblast cell surface by lysyl hydroxylase 3 (LH3) triggers transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) activation and fibroblast differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(22):13763–13778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ikenaka Y, Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in the TIMP-1 transgenic mouse model. Int J Cancer. 2003;105(3):340–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Plewka A, Madej P, Plewka D, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of selected pro-inflammatory factors in uterine myomas and myometrium in women of various ages. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2013;51(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Protic O, Toti P, Islam MS, et al. Possible involvement of inflammatory/reparative processes in the development of uterine fibroids. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;364(2):415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214(2):199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang Y, Feng G, Wang J, et al. Differential effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression in human myometrial and uterine leiomyoma smooth muscle cells. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(1):61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Islam MS, Catherino WH, Protic O, et al. Role of activin-A and myostatin and their signaling pathway in human myometrial and leiomyoma cell function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):E775–E785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nair S, Al-Hendy A. Adipocytes enhance the proliferation of human leiomyoma cells via TNF-alpha proinflammatory cytokine. Reprod Sci. 2011;18(12):1186–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thota C, Farmer T, Garfield RE, Menon R, Al-Hendy A. Vitamin D elicits anti-inflammatory response, inhibits contractile-associated proteins, and modulates Toll-like receptors in human myometrial cells. Reprod Sci. 2013;20(4):463–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu S, Chen YH, Tan ZX, et al. Vitamin D3 pretreatment regulates renal inflammatory responses during lipopolysaccharide-induced acute kidney injury. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen YH, Yu Z, Fu L, et al. Vitamin D3 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced placental inflammation through reinforcing interaction between vitamin D receptor and nuclear factor kappa B p65 subunit. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malik M, Britten JL, Cox J, et al. Cytokine regulation central to ulipristal mediated leiomyoma treatment. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):e280. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ikhena DE, Liu S, Kujawa S, Bulun S, Yin P. Silibinin inhibits progesterone induced RANKL expression in human uterine leiomyoma cells. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3):e280. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tal R, Segars JH. The role of angiogenic factors in fibroid pathogenesis: potential implications for future therapy. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(2):194–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Xu Q, Ohara N, Chen W, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 down-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor, adrenomedullin and their receptors and modulates progesterone receptor content in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(9):2408–2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mantell DJ, Owens PE, Bundred NJ, Mawer EB, Canfield AE. 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3) inhibits angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Circ Res. 2000;87(3):214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chung I, Han G, Seshadri M, et al. Role of vitamin D receptor in the antiproliferative effects of calcitriol in tumor-derived endothelial cells and tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 2009;69(3):967–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]