Abstract

Stem cells residing in the periodontal ligament (PDL) support the homeostasis of the periodontium, but their in vivo identity, source(s), and function(s) remain poorly understood. Here, using a lineage-tracing mouse strain, we identified a quiescent Wnt-responsive population in the PDL that became activated in response to tooth extraction. The Wnt-responsive population expanded by proliferation, then migrated from the PDL remnants that remained attached to bundle bone, into the socket. Once there, the Wnt-responsive progeny upregulated osteogenic protein expression, differentiated into osteoblasts, and generated the new bone that healed the socket. Using a liposomal WNT3A protein therapeutic, we showed that a single application at the time of extraction was sufficient to accelerate extraction socket healing 2-fold. Collectively, these data identify a new stem cell population in the intact periodontium that is directly responsible for alveolar bone healing after tooth removal.

Keywords: tooth extraction, periodontal ligament, Wnt3 protein, Axin2, cell lineages, bone regeneration

Introduction

The periodontal ligament (PDL) is a fibrous connective tissue that attaches the teeth to alveolar bone. It has long been postulated (Barrett and Reade 1981; Gould 1983; McCulloch and Bordin 1991) that the PDL contains a stem cell population, which supports homeostasis of the cementum covering the tooth surface, the alveolar bone, and the PDL itself. This postulation presumes the PDL stem cell is capable of differentiating into a cementoblast, an osteoblast, and a PDL fibroblast. In support of this model, cells isolated from the human molar PDL express mesenchymal stem cell markers like STRO-1 and CD146/MUC18 and, if cultured under defined conditions, are capable of differentiating into cementoblast-like cells, adipocytes, and collagen-forming cells (Seo et al. 2004). These so-called PDL stem cells (PDLSCs) have been employed in multiple in vivo and in vitro models of tissue injury and repair (Zhu et al. 2015). Their identities, function(s), and location(s) in an intact periodontium, however, remain elusive.

Some insights into the nature of this in vivo stem cell population have come with the use of a lineage-tracing mouse strain, wherein a population of α–smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)–positive cells can give rise to osteoblasts, fibroblasts, and cementoblasts during postnatal tooth development and in response to an acute PDL injury (Roguljic et al. 2013). We were interested in signaling pathways that potentially governed the self-renewal and differentiation of this stem cell population.

Wnt signaling regulates the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells. Axin2 expression is a direct target of Wnt signaling (Jho et al. 2002; Lustig et al. 2002), and Axin2-expressing, Wnt-responsive cells are recognized as stem/progenitor cells in wide variety of tissues (van Amerongen et al. 2012; Bowman et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2015). In this study, we investigated the identity, functions, and locations of Wnt-responsive cells in both the intact PDL and the PDL retained in the socket after tooth extraction. Using a tamoxifen-inducible Axin2CreERT2/+ strain crossed with a R26RmTmG/+ reporter strain, we genetically labeled Wnt-responsive cells and then lineage-traced their descendants. We show that Wnt-responsive cells and their progeny comprise a quiescent population residing with the PDL proper. This population becomes mitotically active in response to tooth extraction and ultimately gives rise to osteoblasts that completely heal the extraction socket. Since Wnt-responsive cells actively contribute to the healing, therapies that enhance the number or activity of Wnt-responsive cells have the potential to hasten tooth extraction socket healing. We therefore applied a liposome-stabilized form of WNT3A to a fresh extraction socket and demonstrated that a single dose was sufficient to double the rate of new alveolar bone formation.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Surgeries

Stanford Committee on Animal Research approved all protocols (#13146). Axin2CreERT2/+;R26RmTmG/+ mice (#018867 and #007576, respectively), Axin2LacZ/+ mice (#11809809), and ACTb-EGFP mice (#003291) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and housed in a temperature-controlled environment with 12-h light/dark cycles. To induce Cre expression in Axin2CreERT2/+;R26RmTmG/+ mice, tamoxifen (4 mg/25 g body weight) was delivered intraperitoneally (IP) for 3 consecutive days; animals were then sacrificed at the indicated time points. In ACTb-EGFP mice, the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene is under the control of a chicken β-actin promoter and cytomegalovirus enhancer, which results in all cells being identifiable by eGFP expression.

For the tooth extraction, mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, followed by subcutaneous injections of buprenorphine. The mouth was rinsed with sterile saline, and bilateral maxillary first molars (mxM1) were extracted with forceps. Bleeding was controlled by local pressure. After recovery, mice were fed with a soft diet.

The transplantation experiment is described in the online Appendix.

Collagen Gel Preparation and Releasing/Activity Assay

To prepare the L-WNT3A collagen gel, L-WNT3A was pelleted by centrifugation at 4°C, then resuspended in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing 5 mg/mL type I collagen (Gebico). This mixture is liquid at 4°C and forms a gel-like substance at 37°C. L-WNT3A–releasing and activity assay were performed as described (see Appendix).

For micro–computed tomography (µCT), histology, and cellular assays, see the Appendix.

Statistical Analyses

Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of independent replicates (n ≥ 3). Student’s t test was used to quantify differences between two groups. P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software) was used for these analyses.

This study complies with ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Results

A Subset of PDL Cells Is Wnt Responsive

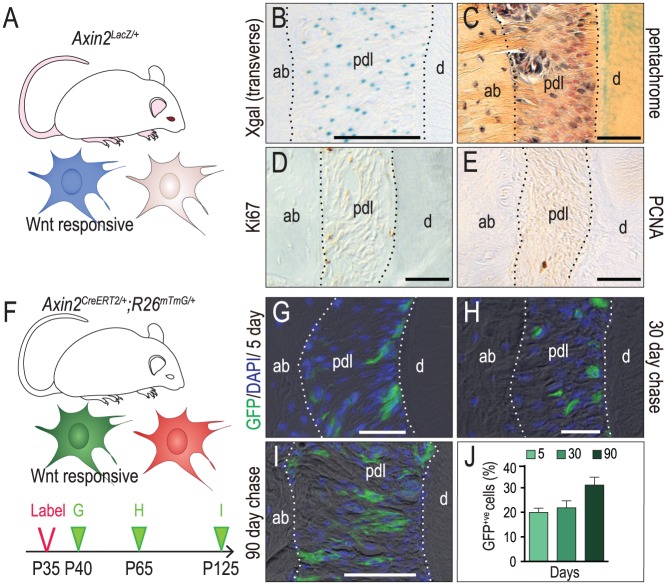

The periodontium is a Wnt-responsive tissue but the identities of the specific cell population(s) that respond to an endogenous Wnt signal—and their fate(s)—are not known. To answer these 2 questions, we used the Axin2LacZ/+ strain of reporter mice (Fig. 1A). Xgal staining showed that Wnt-responsive cells were dispersed throughout the PDL (Fig. 1B, C). Based on the absence of Ki67 and PCNA immunostaining (Fig. 1D, E), the Wnt-responsive cells appeared to be quiescent.

Figure 1.

A subset of periodontal ligament (PDL) cells was Wnt responsive. (A) Schematic of Axin2LacZ/+ mice, in which Wnt-responsive cells were visualized by Xgal staining (blue). (B) Xgal+ve, Wnt-responsive cells in the mxM1 PDL. (C) Pentachrome staining showing the fibrous PDL connecting the tooth to the alveolar bone. In the mxM1 PDL of adult mice, immunostaining for the cell proliferation markers (D) Ki67 and (E) PCNA. (F) Schematic of Axin2CreERT2/+;R26RmTmG/+ mice, in which Wnt-responsive cells transition from expressing membrane Tomato (red) to membrane GFP (green) with the presence of tamoxifen. (G) GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells in the mxM1 PDL of P40 mice, 5 d after initial tamoxifen treatment. After an additional (H) 30 d and (I) 90 d, the GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells were analyzed and counted (J). ab, alveolar bone; d, dentin; pdl, periodontal ligament. Scale bars = 50 µm.

To follow the fate(s) of this Wnt-responsive population (Fig. 1F), we turned to another Wnt reporter strain, Axin2CreErt2/+;R26mTmG/+ (van Amerongen et al. 2012). In this strain, exposure to tamoxifen triggers a recombination event that causes a subset of Wnt-responsive cells to express GFP. After tamoxifen is cleared from the body, which takes ~16 h in mice (Robinson et al. 1991; Morjaria et al. 2014), any increase in the number of GFP+ve cells reflects an expansion in the original Wnt-responsive population.

Mice received tamoxifen for 3 d (the labeling period) and then were sacrificed 2 d after the third dose (the chase period, Fig. 1F). This analysis identified a relatively small population of GFP+ve cells randomly distributed throughout the PDL (Fig. 1G). A second analysis was then performed: the same 5-d labeling period was followed by a 30-d chase. Despite the longer chase period, the Wnt-responsive population had neither expanded nor changed its distribution compared with the shorter chase group (compare Fig. 1H with G). Even after a 90-d chase, the Wnt-responsive population remained relatively limited in size (Fig. 1I; quantified in J). These data, considered along with analyses of the Axin2LacZ/+ strain, demonstrated that the Wnt-responsive population in the adult PDL was either very slow cycling or dormant.

Wnt-Responsive PDL Cells Become Mitotically Active in Response to Tooth Extraction

Tooth extraction stimulates alveolar bone healing (Vieira et al. 2015), and at least some of the cells in the PDL participate in this healing (Devlin and Sloan 2002; Pei et al. 2017). To directly test whether Wnt-responsive cells were part of this PDL population that participated in alveolar bone healing, both mxM1s were extracted from adult Axin2CreErt2/+;R26mTmG/+ mice, in which Wnt-responsive cells were labeled with tamoxifen injection.

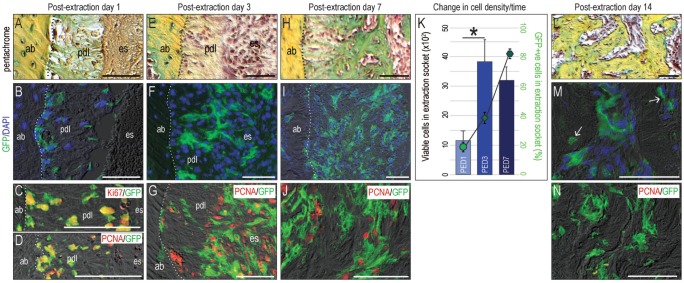

Within 24 h of tooth removal (Fig. 2A), the number of GFP+ve cells residing in the PDL remnants was increased (Fig. 2B) compared with the intact state (Fig. 1G). Colocalization of GFP with 2 different proliferation markers, Ki67 and PCNA, confirmed that the Wnt-responsive population became mitotically active, specifically in response to tooth extraction (Fig. 2C, D). By postextraction day 3 (PED3), the Wnt-responsive population had expanded further (Fig. 2E, F). Colocalization of GFP with PCNA confirmed that most GFP+ve cells were now actively proliferating (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2.

Wnt-responsive periodontal ligament (PDL) cells became mitotically active in response to tooth extraction. (A) Representative sagittal tissue sections, stained with pentachrome, on postextraction day (PED) 1, with adjacent tissue sections stained to identify (B) GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells and proliferating cells by (C) Ki67 and (D) PCNA. On PED3, (E) pentachrome staining identified the PDL remnants that (F) were populated by GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells. (G) Costaining with PCNA demonstrates that Wnt-responsive cells were actively proliferating. On PED7, (H) the residual PDL mineralized and (I) the number of GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells reached its zenith. (J) Some GFP+ve cells were PCNA+ve. (K) The number of viable (DAPI+ve) cells was counted in a specified region of interest (ROI); the largest increase in cell density coincided with the peak of Wnt-responsive cells. *P < 0.0001. By PED14, (L) the mineralized PDL remnants and adjacent intact alveolar bone were indistinguishable by pentachrome staining, and (M) most GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells had differentiated into osteoblasts and osteocytes (arrow). (N) Most of GFP+ve cells were negative to PCNA staining. ab, alveolar bone; pdl, periodontal ligament; es, extraction socket. Scale bars = 50 µm.

By PED7, PDL remnants began to mineralize (Fig. 2H), and the number of Wnt-responsive cells reached its zenith (Fig. 2I; quantified in K, Appendix Fig. 1). Some of progeny of the original Wnt-responsive population continued to maintain their mitotically active status (Fig. 2J). Thus, following a proliferative burst, there was a gradual reduction in mitotic activity commensurate with the onset of mineralization.

By PED14, new bone filled the healed extraction site (Fig. 2L), and progeny of the original GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive population were either osteoblasts or osteocytes surrounded by newly mineralized matrix (Fig. 2M, Appendix Fig. 2). By this timepoint, proliferating cells were no longer detectable (Fig. 2N).

Descendants of the Wnt-Responsive Population Differentiate into Alveolar Bone Osteoblasts

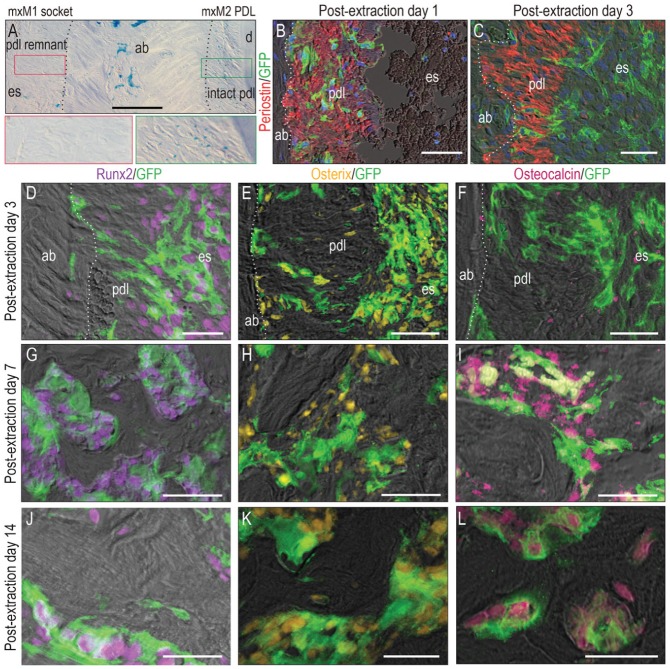

We noticed that PDL remnants lost their Wnt responsiveness quickly after tooth extraction. This was readily detectable on PED3 when we compared the Wnt-responsive state of the intact PDL (green box in Fig. 3A) with the Wnt-responsive state of the PDL remnants left after mxM1 extraction (red box in Fig. 3A) in Axin2LacZ/+ reporter mice. Why did the PDL lose its Wnt responsiveness?

Figure 3.

Descendants of the Wnt-responsive population differentiated into alveolar bone osteoblasts. (A) Xgal+ve, Wnt-responsive cells in the periodontal ligament (PDL) remnants lining the mxM1 extraction socket (red box) and in the intact mxM2 PDL (green box). (B) Costaining with Periostin shows that initially (on postextraction day [PED] 1), GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive cells were restricted in the PDL. (C) By PED3, the Wnt-responsive population had migrated away from the PDL and into the extraction socket. On PED3, costaining with (D) Runx2 and (E) Osterix demonstrated that most Wnt-responsive GFP+ve cells were osteoprogenitors. Costaining with (F) osteocalcin confirmed that those GFP+ve progenitors were not fully differentiated yet. On PED7, as new bone formed, GFP+ve cells were aligned with the new bone and positive for (G) Runx2, (H) Osterix, and (I) Osteocalcin. By PED14, GFP+ve cells were still positive for (J) Runx2, (K) Osterix, and (L) Osteocalcin. ab, alveolar bone; d, dentin; pdl, periodontal ligament; es, extraction socket. Scale bars = 50 µm.

The answer became obvious when we used the lineage-tracing Axin2CreErt2/+; R26mTmG/+ strain to track the migration of the Wnt-responsive PDL population. For example, on PED1, GFP+ve cells costained with the PDL extracellular matrix marker, Periostin (Fig. 3B). On PED3, GFP+ve cells were no longer associated with the Periostin+ve domain (Fig. 3C). Instead, Wnt-responsive cells were predominantly located in the center of the socket on PED5 (Appendix Fig. 3). Therefore, the most plausible explanation for the loss of Wnt responsiveness in the PDL remnants was that this cell population migrated out and away from the Periostin+ve PDL fibers where they had initially resided. In support of this interpretation, costaining Runx2 and Osterix with GFP confirmed that during the putative migratory phase (i.e., PED3), the Wnt-responsive population were osteoprogenitors (Fig. 3D–F). Only after migration was complete (i.e., PED7) did the Wnt-responsive population become fully differentiated (Fig. 3G–I). By PED14, GFP+ve osteoblasts were either lining the surfaces of new bone or were osteocytes, encased in the new bone matrix (Fig. 3J–L).

Primary Source of Osteoblasts That Heal the Extraction Socket Reside in the PDL

We drew 3 conclusions from the preceding experiments. First, PDL has a quiescent population of Wnt-responsive cells. Second, this once-dormant population became mitotically active by injury, here in the form of tooth extraction (Fig. 2). Third, this same mitotically active Wnt-responsive progeny eventually differentiated (Fig. 3). Ultimately, it was these GFP+ve, Wnt-responsive osteoblasts that deposited the new bone matrix (Figs. 2, 3) that healed the extraction socket.

We wondered about the initial source(s) of this Wnt-responsive population. Although we had identified GFP+ve cells in the intact PDL (Fig. 1) and the injured PDL (Fig. 2), this did not rule out the possibility that the Wnt-responsive population healing the defect had migrated from surrounding bone or nearby vascular spaces into the socket after extraction.

To clarify that the PDL contained a population of Wnt-responsive stem/progenitor cells that were capable of generating new alveolar bone, we performed a transplantation experiment: mxM1s were extracted from mice carrying a constitutively active GFP transgene; consequently, all cells deriving from the donor were identifiable by GFP expression (Okabe et al. 1997). Once extracted, the crown and pulp were removed from the molars, and the remaining roots, along with their attached PDL remnants, were transplanted into critical-sized osteotomies prepared in syngeneic, non-GFP host mice (Appendix Fig. 4A, B). This strategy ensured that the only viable cells that were transplanted were those that resided within the PDL remnants decorating the extracted root tips.

Seven days later, the site was evaluated: the gap between the transplanted root and the osteotomy was populated by GFP+ve cells (Appendix Fig. 4C). Costaining with GFP and the osteoblast marker, Osteocalcin (Appendix Fig. 4D), confirmed that most transplanted PDL cells were mature osteoblasts (Appendix Fig. 4E) that were directly responsible for depositing new mineralized matrix around the transplanted roots (Appendix Fig. 4F). While this transplantation experiment does not eliminate the possibility that there is a cellular contribution from surrounding bone or nearby vascular spaces to extraction socket healing, it does directly demonstrate that cells within the PDL proper can differentiate into matrix-secreting osteoblasts.

L-WNT3A Accelerates Extraction Socket Healing

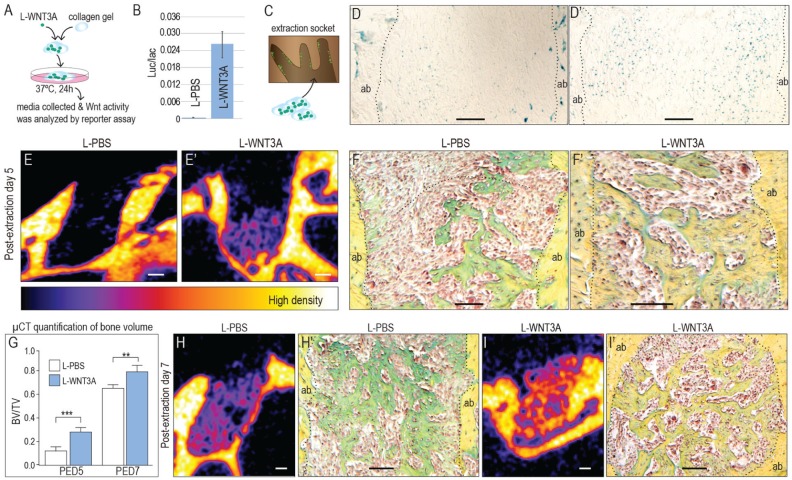

Could we accelerate extraction socket healing by amplifying the endogenous Wnt signal? We used a stabilized form of WNT3A protein reconstituted in association with a liposome to amplify Wnt signaling. To retain the liposomal WNT3A (L-WNT3A) in the fresh extraction socket, we mixed it with a collagen gel (Fig. 4A). Activity of L-WNT3A in the collagen gel was confirmed using a cell reporter assay (Fig. 4B). Immediately following mxM1 extraction, a single application of L-WNT3A in a collagen gel was delivered to the socket (Fig. 4C). Controls received an identical liposomal formulation of PBS (L-PBS) in the same collagen gel.

Figure 4.

Extraction socket healing was significantly accelerated by a single dose of L-WNT3A. (A) To retain L-WNT3A in the extraction socket, the material was mixed with an inert collagen gel, and then (B) activity of the L-WNT3A therapeutic was confirmed using an LSL cell reporter assay. (C) Immediately after tooth extraction, the L-WNT3A containing gel (which is liquid at 4°C and solidifies at 37°C) was injected into the socket. Five days later, Xgal staining showed more Wnt-responsive cells in the (D′) L-WNT3A–treated group compared with (D) the group that received the liposomal formulation of phosphate-buffered saline (L-PBS). Micro–computed tomography (µCT) analyses were performed on extraction sockets treated with (E) collagen gel + L-PBS and (E′) collagen gel + L-WNT3A. At this same time point, pentachrome staining identified new mineralized matrix in extraction sockets treated with (F) L-PBS and (F′) L-WNT3A. (G) Quantification of bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) from µCT results. On postextraction day (PED) 7, (H) extraction sockets treated with collagen gel + L-PBS exhibited new bone formation, (H′) confirmed by pentachrome staining. At the same time point, (I) extraction sockets treated with the collagen gel + L-WNT3A had more bone, (I′) confirmed by histology; quantified in (G). ab, alveolar bone; pdl, periodontal ligament; es, extraction socket. Scale bar = 100 µm. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Xgal staining confirmed that L-WNT3A amplified Wnt signaling in the extraction socket (Fig. 4D, D′). On PED5, µCT imaging and histological analyses demonstrated that the L-WNT3A–treated sockets had more than twice the amount of bone as L-PBS–treated extraction sockets (Fig. 4E, E′, F, F′; quantified in G; Appendix Movies 1, 2).

By PED7, Xgal staining indicated that the L-WNT3A group still had more Wnt-responsive cells in the extraction socket (Appendix Fig. 3B, B′). In L-PBS–treated extraction sockets, µCT imaging showed the first evidence of new bone matrix (Fig. 4H); in contrast, bone matrix filling the L-WNT3A–treated extraction sockets had a significantly higher bone volume/total volume (BV/TV) (Fig. 4I; quantified in G, Appendix Movies 3, 4). Pentachrome staining confirmed that the bone in the L-WNT3A–treated group had a more mature, dense lamellar organization (Fig. 4H′, I′). Collectively, these data indicated that an already robust bone-healing process could be significantly accelerated by amplifying Wnt signaling via a protein therapeutic.

Discussion

Quiescence vs. Mitotic Activity in a Stem/Progenitor Population

In the intact adult periodontium, there exists a quiescent, Wnt-responsive population that is associated with PDL fibers (Fig. 1). Upon injury, this Wnt-responsive population becomes mitotically active (Fig. 2). The cells, which at this point are proliferating osteoprogenitors, migrate away from the fibrous PDL into the extraction socket, where they then upregulate the expression of osteogenic proteins (Fig. 3). The new bone that heals the extraction socket is derived from the initially quiescent Wnt-responsive population. Collectively, these behaviors by Wnt-responsive cells are reminiscent of a stem cell population.

This Wnt-responsive population can be contrasted with an α-SMA–expressing population that also exhibits some stem properties (Roguljic et al. 2013). While our data show that the Wnt-responsive population was quiescent (Fig. 1), the α-SMA population in PDL is reported to be highly proliferative (Roguljic et al. 2013). This difference may simply be due to the age of the mice at the time of examination: in Roguljic’s experiment, the animals were ~3 wk old, when most cells in the PDL are actively proliferating (Huang, Salmon, et al. 2016; Lim, Liu, Mah, et al. 2014). In contrast, our study was conducted on animals ranging from 1 to 4 mo, when proliferation is almost nonexistent in the PDL (Huang, Liu, et al. 2016). If the α-SMA–expressing and Wnt-responsive populations overlap, then these contradictory observations may reflect age-related differences in mitotic activity of a stem population. It is equally feasible that the α-SMA–expressing and Wnt-responsive populations are distinct from one another, which then intimates that both quiescent and active stem cell populations reside within the PDL.

Quiescence is an actively maintained state that allows cells to withstand metabolic stress, yet still permits them to reenter the cell cycle rapidly when needed (Li and Clevers 2010; Cheung and Rando 2013). In tissues like hair and the intestine, quiescent and active stem cells are maintained at separate but adjoining locations. In those tissues, active stem cells are derived from the parent quiescent stem population and are responsible for maintaining the normal turnover of the tissue. The quiescent population, on the other hand, functions as a reserve pool that only becomes activated in response to extensive tissue damage (Li and Clevers 2010). This is an apt description of the Wnt-responsive population identified here (Figs. 1–3).

Does the PDL Function as a Reservoir for Stem Cells?

In multiple locations of the skeleton, the periosteum is responsible for generating new bone (Lin et al. 2014). Is it possible that the PDL serves a similar function, as a reservoir of stem cells for alveolar bone and cementum homeostasis? Indirect evidence suggests that it does; for example, the rate of new bone formation is significantly faster on PDL-facing surfaces of alveolar bone compared to its rate on other surfaces (Ren et al. 2015). If the PDL was the major source of alveolar bone osteoblasts, then its removal should translate into fewer osteoprogenitor cells. Although this does not happen immediately, well-described alveolar ridge resorption occurs as a consequence of tooth extraction (Schropp et al. 2003), which may be related to the loss of a PDL-derived stem cell pool.

Wnt Signaling Maintains Homeostasis of the Periodontium

The Wnt signaling pathway participates in maintenance of the periodontium (Rooker et al. 2010; Lim, Liu, Cheng, et al. 2014; Lim, Liu, Hunter, et al. 2014; Tamura and Nemoto 2016). Reducing or eliminating endogenous Wnt signaling causes a pathological widening of the PDL space and leads a dramatic reduction in both alveolar bone volume and density, as well as a loss of cementum (Lim, Liu, Hunter, et al. 2014). Conversely, genetically amplifying the Wnt signal results in excessive cementum formation and bone accrual (Tu et al. 2015). These data indirectly suggest that the level of endogenous Wnt signaling controls the balance between fibrous tissue and osseous tissues. This balance is tipped when there is an injury: extensive tissue damage activates—and amplifies—the endogenous Wnt signal, and because of this elevated state of Wnt signaling, osseous tissues form, presumably at the expense of a fibrous PDL. We observe an even more robust outcome when exogenous Wnt is supplied: the number of Wnt-responsive cells significantly increased, which in turn significantly increased the rate of bone formation (Fig. 4).

There are 2 limitations to this study. First, we focused primarily on biological factors that influence extraction socket healing, but physical factors also play an important role in this process. For example, cells residing in the fibrous PDL may differentiate into bone rather than fibroblasts because of the absence of a mechanical load. A second limitation is that the source of the endogenous Wnt signal generated by tooth extraction is still unknown. Wnt signaling is a short-range intercellular signal (Clevers et al. 2014), and studies in stem cell maintenance (Lim et al. 2016) suggest an autocrine model whereby Wnt-responsive Axin2-expressing cells are responsible for expressing Wnt ligands (Babb et al. 2017).

If these data hold true for the periodontium, then all efforts should be made to preserve the PDL in the extraction socket. The caveat is that if the PDL is diseased, then its ability to act as a stem cell reservoir is likely to be compromised.

Conclusion

Few therapies effectively prevent alveolar ridge resorption (Morjaria et al. 2014). Data shown here suggest a strategy that preserves or enhances the Wnt-responsive population for preventing alveolar bone loss. Clinical trial data demonstrate that the anti-Sclerostin antibody Romosozumab increases bone accrual (Saag et al. 2017), but inhibiting a Wnt inhibitor only transiently amplifies Wnt signaling (van Lierop et al. 2014; Rosen 2017). Since Wnt signaling declines with age (Rauner et al. 2008; Hofmann et al. 2014; Farr et al. 2015; Jing et al. 2015), blocking a Wnt inhibitor should theoretically return Wnt signaling levels only back to baseline. Augmenting the local Wnt signal, on the other hand (e.g., Fig. 4), may be a more effective therapeutic strategy to stimulate bone repair and prevent alveolar ridge resorption, especially in an older patient population.

Author Contributions

X. Yuan, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; X. Pei, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; Y. Zhao, U.S. Tulu, B. Liu, contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; J.A. Helms, contributed to conception, design, data analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, DS_10.1177_0022034518755719 for A Wnt-Responsive PDL Population Effectuates Extraction Socket Healing by X. Yuan, X. Pei, Y. Zhao, U.S. Tulu, B. Liu, and J.A. Helms in Journal of Dental Research

Acknowledgments

We thank Chih-Hao Chen for help with surgeries.

Footnotes

A supplemental appendix to this article is available online.

This research project was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01DE024000-11) to J.A.H.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: X. Yuan  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8063-9431

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8063-9431

J.A. Helms  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0463-396X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0463-396X

References

- Babb R, Chandrasekaran D, Carvalho Moreno Neves V, Sharpe PT. 2017. Axin2-expressing cells differentiate into reparative odontoblasts via autocrine Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in response to tooth damage. Sci Rep. 7(1):3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AP, Reade PC. 1981. The relationship between degree of development of tooth isografts and the subsequent formation of bone and periodontal ligament. J Periodontal Res. 16(4):456–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AN, van Amerongen R, Palmer TD, Nusse R. 2013. Lineage tracing with Axin2 reveals distinct developmental and adult populations of Wnt/beta-catenin-responsive neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 110(18):7324–7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung TH, Rando TA. 2013. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 14(6):329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. 2014. Stem cell signaling: an integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 346(6205):1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin H, Sloan P. 2002. Early bone healing events in the human extraction socket. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 31(6):641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr JN, Roforth MM, Fujita K, Nicks KM, Cunningham JM, Atkinson EJ, Therneau TM, McCready LK, Peterson JM, Drake MT, et al. 2015. Effects of age and estrogen on skeletal gene expression in humans as assessed by RNA sequencing. PLoS One. 10(9):e0138347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TR. 1983. Ultrastructural characteristics of progenitor cell populations in the periodontal ligament. J Dent Res. 62(8):873–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann JW, McBryan T, Adams PD, Sedivy JM. 2014. The effects of aging on the expression of Wnt pathway genes in mouse tissues. Age (Dordr). 36(3):9618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Liu B, Cha JY, Yuan G, Kelly M, Singh G, Hyman S, Brunski JB, Li J, Helms JA. 2016. Mechanoresponsive properties of the periodontal ligament. J Dent Res. 95(4):467–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Salmon B, Yin X, Helms JA. 2016. From restoration to regeneration: periodontal aging and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Periodontol 2000. 72(1):19–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho EH, Zhang T, Domon C, Joo CK, Freund JN, Costantini F. 2002. Wnt/beta-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 22(4):1172–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing W, Smith AA, Liu B, Li J, Hunter DJ, Dhamdhere G, Salmon B, Jiang J, Cheng D, Johnson CA, et al. 2015. Reengineering autologous bone grafts with the stem cell activator WNT3A. Biomaterials. 47:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Johnson DT, Luong R, Yu EJ, Cunha GR, Nusse R, Sun Z. 2015. Wnt/β-catenin-responsive cells in prostatic development and regeneration. Stem Cells. 33(11):3356–3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Clevers H. 2010. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 327(5965):542–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WH, Liu B, Cheng D, Williams BO, Mah SJ, Helms JA. 2014. Wnt signaling regulates homeostasis of the periodontal ligament. J Periodontal Res. 49(6):751–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WH, Liu B, Hunter DJ, Cheng D, Mah SJ, Helms JA. 2014. Downregulation of Wnt causes root resorption. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 146(3):337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim WH, Liu B, Mah SJ, Chen S, Helms JA. 2014. The molecular and cellular effects of ageing on the periodontal ligament. J Clin Periodontol. 41(10):935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim X, Tan SH, Yu KL, Lim SB, Nusse R. 2016. Axin2 marks quiescent hair follicle bulge stem cells that are maintained by autocrine Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113(11):E1498–E1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Fateh A, Salem DM, Intini G. 2014. Periosteum: biology and applications in craniofacial bone regeneration. J Dent Res. 93(2):109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig B, Jerchow B, Sachs M, Weiler S, Pietsch T, Karsten U, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Schlag PM, Birchmeier W, et al. 2002. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 22(4):1184–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch CA, Bordin S. 1991. Role of fibroblast subpopulations in periodontal physiology and pathology. J Periodontal Res. 26(3 Pt 1):144–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morjaria KR, Wilson R, Palmer RM. 2014. Bone healing after tooth extraction with or without an intervention: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 16(1):1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. 1997. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 407(3):313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei X, Wang L, Chen C, Yuan X, Wan Q, Helms JA. 2017. Contribution of the PDL to osteotomy repair and implant osseointegration. J Dent Res. 96(8):909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauner M, Sipos W, Pietschmann P. 2008. Age-dependent wnt gene expression in bone and during the course of osteoblast differentiation. Age (Dordr). 30(4):273–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Han X, Ho SP, Harris SE, Cao Z, Economides AN, Qin C, Ke H, Liu M, Feng JQ. 2015. Removal of sost or blocking its product sclerostin rescues defects in the periodontitis mouse model. FASEB J. 29(7):2702–2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SP, Langan-Fahey SM, Johnson DA, Jordan VC. 1991. Metabolites, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of tamoxifen in rats and mice compared to the breast cancer patient. Drug Metab Dispos. 19(1):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roguljic H, Matthews BG, Yang W, Cvija H, Mina M, Kalajzic I. 2013. In vivo identification of periodontal progenitor cells. J Dent Res. 92(8):709–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooker SM, Liu B, Helms JA. 2010. Role of Wnt signaling in the biology of the periodontium. Dev Dyn. 239(1):140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen CJ. 2017. Romosozumab—promising or practice changing? N Engl J Med. 377(15):1479–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saag KG, Petersen J, Brandi ML, Karaplis AC, Lorentzon M, Thomas T, Maddox J, Fan M, Meisner PD, Grauer A. 2017. Romosozumab or alendronate for fracture prevention in women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 377(15):1417–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schropp L, Wenzel A, Kostopoulos L, Karring T. 2003. Bone healing and soft tissue contour changes following single-tooth extraction: a clinical and radiographic 12-month prospective study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 23(4):313–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, Young M, Robey PG, Wang CY, Shi S. 2004. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 364(9429):149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M, Nemoto E. 2016. Role of the Wnt signaling molecules in the tooth. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 52(4):75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu X, Delgado-Calle J, Condon KW, Maycas M, Zhang H, Carlesso N, Taketo MM, Burr DB, Plotkin LI, Bellido T. 2015. Osteocytes mediate the anabolic actions of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in bone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112(5):E478–E486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amerongen R, Bowman AN, Nusse R. 2012. Developmental stage and time dictate the fate of Wnt/β-catenin-responsive stem cells in the mammary gland. Cell Stem Cell. 11(3):387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lierop AH, Moester MJ, Hamdy NA, Papapoulos SE. 2014. Serum Dickkopf 1 levels in sclerostin deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 99(2):E252–E256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira AE, Repeke CE, Ferreira Junior Sde B, Colavite PM, Biguetti CC, Oliveira RC, Assis GF, Taga R, Trombone AP, Garlet GP. 2015. Intramembranous bone healing process subsequent to tooth extraction in mice: micro–computed tomography, histomorphometric and molecular characterization. PLoS One. 10(5):e0128021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Cen L, Wang J. 2015. PDL regeneration via cell homing in delayed replantation of avulsed teeth. J Transl Med. 13:357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, DS_10.1177_0022034518755719 for A Wnt-Responsive PDL Population Effectuates Extraction Socket Healing by X. Yuan, X. Pei, Y. Zhao, U.S. Tulu, B. Liu, and J.A. Helms in Journal of Dental Research