Abstract

Oral lichen planus is categorized as a potentially malignant condition by the World Health Organization; however, some argue that only lichen planus with dysplasia have malignant potential. Many pathologists call lichen planus with dysplasia “dysplasia with lichenoid mucositis (LM)” or “LM with dysplasia.” Previous research has shown that certain high-risk patterns of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in dysplastic lesions are associated with significantly increased cancer risk. However, LM without dysplasia lacks such molecular patterns, supporting the hypothesis that LM, by itself, is not potentially malignant and that only those with dysplasia have malignant potential. To further investigate the premalignant nature of LM with dysplasia, this study compared the rate of malignant progression of dysplasia with LM with that of dysplasia without LM. Patients from a population-based prospective cohort study with >10 y of follow-up were analyzed. Study eligibility included a histological diagnosis of a primary low-grade dysplasia with or without LM. A total of 446 lesions in 446 patients met the selection criteria; 373 (84%) were classified as dysplasia without LM, while 73 (16%) were classified as dysplasia with LM. Demographic and habit information, clinical information, and outcome (progression) were compared between the 2 groups. Forty-nine of 373 cases of dysplasia (13%) progressed compared to 8% (6/73) of dysplasia with LM. However, the difference was not statistically different (P = 0.24). The 3- and 5-y rate of progression did not differ between the groups (6.7% and 12.5% for dysplasia without LM and 2.9% and 6.6% for those with LM; P = 0.36). Progression was associated with nonsmoking, location at a high-risk site, and diagnosis of moderate dysplasia regardless of whether LM was present or not. Dysplasia with or without LM had similar cancer risk, and dysplasia should not be discounted in the presence of LM.

Keywords: oral lichen planus, epithelial neoplasms, precancerous conditions, leukoplakia, oral pathology, oral epithelial dysplasia

Introduction

Lichenoid mucositis (LM) refers to a group of mucosal lesions (e.g., lichen planus and LM from contact with dental materials or intake of drugs) that are characterized by a band-like lympho-histiocytic inflammation in the immediate subepithelial region (van der Meij et al. 2003). It is hypothesized that such inflammation results from both antigen-specific cell-mediated immunity in response to antigenicity changes in the oral epithelial lining cells as well as nonspecific mechanisms such as mast cell degranulation and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activation in oral lichen planus lesions (Sugerman et al. 2002; Epstein et al. 2003). If an allergen can be identified, then a diagnosis of LM can be made. A diagnosis of lichen planus can only be made after ruling out LM, in which case one is able to identify the allergen. Consequently, LM from allergic contact or drugs could be cured by withdrawal of the allergen but not lichen planus. The diagnosis of lichen planus therefore requires both histological assessment and clinical information. Unfortunately, pathologists often do not have the clinical information and therefore will tend to diagnose an LM as an oral lichen planus and hence artificially inflate the incidence of lichen planus.

Oral lichen planus is categorized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a potentially malignant condition (Barnes et al. 2005); however, there are heated debates as to whether lichen planus should be considered premalignant. In 1985, Krutchkoff and Eisenberg reviewed literature on cancer progression of oral lichen planus and found that all reported oral lichen planus with cancer progression had shown low-grade dysplastic changes. Consequently, they concluded that lichen planus without dysplasia was not premalignant, and only those with dysplasia were premalignant. They coined the term lichenoid dysplasia for these dysplastic lesions with LM; however, the term was not widely used, and many called such lesions dysplasia with LM, LM with dysplasia, or lichen planus with dysplasia. They hypothesized that the reason for lichen planus being classified as premalignant was due to the failure to recognize low-grade dysplasia in the presence of lichenoid inflammation.

Previously, we developed and validated a risk prediction model that showed that certain patterns of loss of heterozygosity (LOH) are significantly associated with the risk of malignant progression in oral premalignant lesions. In this model, low-grade dysplasia (mild/moderate dysplasia) with intermediate-risk and high-risk LOH patterns demonstrated a 3.8-fold and 33-fold increased cancer risk, respectively, compared to those with a low-risk LOH pattern (Zhang et al. 2012). Previously, to investigate the possible premalignant nature of LM with or without dysplasia, we compared the LOH patterns of these lesions with reactive hyperplasia and low-grade dysplasia without LM. Our results showed that LM without dysplasia and reactive hyperplasia lacked the genetic characteristics of oral premalignant lesions (Zhang et al. 1997), whereas LM with dysplastic changes showed similar genetic alterations to those of low-grade dysplasia without lichenoid changes (Zhang et al. 2000), supporting the hypothesis that LM per se is not premalignant and that only LM with dysplasia is premalignant.

The objective of this study was to further investigate the premalignant nature of LM with dysplasia. This study compared the proportion and the rate of malignant progression of low-grade dysplasia with LM with that of low-grade dysplasia without LM. By determining the risk of progression of dysplasia with LM, we seek to better define this unique subset of patients and ultimately aid in the diagnosis and management of this disease.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population

This cohort study involved patients who were enrolled in an ongoing Oral Cancer Prediction Longitudinal (OCPL) study between January 1, 1997, and October 4, 2013. Participants in the study were identified through a centralized population-based biopsy service, the BC Oral Biopsy Service, where community dentists and specialists across British Columbia (population 4.8 million, in 2016) send biopsies for histological diagnosis. Patients with a diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia (regardless of whether there is accompanying LM) were referred by these community clinicians, upon recommendation from the Oral Biopsy Service, for follow-up in oral dysplasia clinics, where they were invited to participate in the OCPL study. Study protocol and ethical approval were obtained from the University of British Columbia and BC Cancer Agency Research Ethics Board, and participants were recruited to the study using written informed consent. Study eligibility included a histologically confirmed diagnosis of low-grade (mild or moderate) oral epithelial dysplasia with or without LM, and the patients had no history of oral cancer. A total of 446 lesions in 446 patients met the selection criteria and were included in the present analysis, with a median follow-up time of 63.8 mo (7.5 to 258.4 mo). To address and reduce potential bias from interobserver variability, the slides of the index biopsies as well as those of subsequent biopsies from the index biopsy sites were reviewed by an oral pathologist (L.Z.), and the diagnostic criteria were those of the WHO and studies from authorities in the field (Krutchkoff and Eisenberg 1985; van der Meij et al. 2003; Barnes et al. 2005; Patil et al. 2015). Of the 446 lesions, 373 lesions were low-grade dysplasia without LM, and 73 lesions were low-grade dysplasia with LM. LM was noted in 68 lesions in the subsequent biopsies from the 373 lesions that initially showed no lichenoid changes, resulting in a total of 141 lesions with LM ever. Of the 446 lesions, 296 cases have been reported in a previous study, but that study was not aimed at comparing dysplasia with and without LM but rather at the relationship between the LOH pattern in dysplasia and outcome (Zhang et al. 2012).

Clinical Pathological Data, Treatment, and Follow-up

The OCPL study collects demographic data, clinical information, and tobacco and alcohol habits at study entry. The primary end point of this study was time from index biopsy to histologically confirmed progression to severe dysplasia or higher, occurring at the same anatomical site as the index biopsy. Inclusion of severe dysplasia as the progression end point was based on our findings that without treatment, progression occurred in 32% of patients in 3 y and 59% in 5 y (Zhang et al. 2016).

Statistical Analysis and Reporting

Data analyses were carried out using SPSS Version 25.0 software (SPSS, Inc.). The threshold for significance was set at P < 0.05, and all tests were 2-tailed. The inferential analysis included separate bivariate analyses between each independent and dependent variable. Categorical variables were tested using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when >20% of cells contained expected frequencies of <5. Quantitative variables were tested using an independent samples t test; those that were not normally distributed were tested with the Mann-Whitney U test. To control for potential confounding, demographic, risk habit, and clinical variables were assessed for significant differences between groups. Missing data were deemed to be minimal, likely unrelated to observed responses, and handled by available case analysis. Time to end point was calculated from date of the index biopsy to end point date or to last follow-up date (as of December 22, 2016), if no progression occurred. Since every patient had a different length of follow-up, time-to-progression curves and 3-y and 5-y progression rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis and the log rank test. Hazard ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. This observational study conformed with Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for cohort studies.

Results

Of the 446 lesions that were included in the analysis, 373 (84%) were classified as low-grade dysplasia without LM, while 73 (16%) were classified as low-grade dysplasia with LM. Table 1 compares patient characteristics between the 2 groups. There were no significant differences in age, sex, ethnicity, and smoking habit between the groups, nor were there any significant differences in site, number of lesions, or length of follow-up time.

Table 1.

Comparison of Oral Epithelial Dysplasia with and without Lichenoid Mucositis According to Demographic, Risk Habit Information, and Clinical Features.

| Characteristic | All | Low-Grade Dysplasia without LM | Low-Grade Dysplasia with LM | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 446 (100) | 373 (100) | 73 (100) | |

| Age at diagnosis (n = 445)a | ||||

| Mean ± SD, y | 57.3 ± 11.4 | 57.5 ± 11.6 | 56.0 ± 10.7 | .289 |

| Age category (n = 445)a | ||||

| <40 y | 25(6) | 22 (6) | 3 (4) | .719 |

| 40 to 60 y | 246 (55) | 203 (55) | 43 (59) | |

| >60 y | 174 (39) | 147 (39) | 27 (37) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 229 (51) | 199 (53) | 30 (41) | .055 |

| Female | 217 (49) | 174 (47) | 43 (59) | |

| Ethnicity (n = 445)a | ||||

| Caucasian | 375 (84) | 318 (85/85) | 57 (79) | .194 |

| Non-Caucasian | 70 (16) | 55 (79/15) | 15 (21) | |

| Smoking historyb (n = 440)a | ||||

| Never | 139 (32) | 112 (81/30) | 24 (38) | .238 |

| Ever | 301 (68) | 256 (85/70) | 45 (62) | |

| Risk of lesion sitec | ||||

| Low risk | 178 (40) | 148 (40) | 30 (41) | .821 |

| High risk | 268 (60) | 225 (60) | 43 (59) | |

| Multiple lesion sites | ||||

| No | 426 (96) | 355 (83/95) | 71 (97) | .756 |

| Yes | 20 (4) | 18 (90/5) | 2 (3) | |

| Length of follow-upd | ||||

| Median months of follow-up (range) | 63.8 (7.5 to 258.4) | 64.1 (7.5 to 258.4) | 63.0 (13.2 to 168.3) | .798 |

Values are presented as number (column %) unless otherwise indicated.

Low-grade dysplasia, mild or moderate dysplasia; LM, lichenoid mucositis.

One participant declined to provide date of birth, 1 participant declined to provide ethnicity, and 5 participants declined to provide smoking history.

Never smoker, <100 cigarettes in lifetime; ever smoker, consumption of >100 cigarettes in lifetime.

High risk, floor of mouth and tongue; low risk, all other sites.

Months to last follow-up or progression, whichever occurred first.

During the study period, of the 446 lesions, 55 (12%) progressed: 26 to severe dysplasia, 4 to carcinoma in situ, and 25 to squamous cell carcinoma. Age at diagnosis, sex, and ethnicity were not associated with progression (Table 2). A significantly higher proportion of progression occurred in never smokers. Never smokers were almost twice as likely to progress compared to than those who smoked (95% CI, 1.06 to 3.37; P = 0.03). Lesion site was significantly associated with progression. A lesion in a high-risk site (the floor of mouth or the tongue) possessed a >3-fold increased risk of progression compared to lower risk sites (such as the gingiva, palate, or buccal or labial mucosa) (odds ratio [OR], 3.89; 95% CI, 1.85 to 8.17; P < 0.001). A diagnosis of moderate dysplasia, regardless of whether LM was present, was associated with progression. Lesions with a diagnosis of moderate dysplasia were 2.3 times more likely to progress compared to those with a diagnosis of mild dysplasia (95% CI, 1.31 to 4.18; P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Distribution of Cases According to Outcome.

| Characteristic | All | No Progressiona | Progressiona | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 446 | 391 (88) | 55 (12) | ||

| Age at diagnosis (n = 445)b | |||||

| Mean ± SD, y | 57.3 ± 11.4 | 57.5 ± 11.4 | 55.7 ± 11.4 | 0.272 | |

| Age category (n = 445)b | |||||

| <40 y | 25 | 21 (84) | 4 (16) | 0.693 | 1 |

| 40 to 60 y | 246 | 214 (87) | 32 (13) | 0.79 (0.25 to 2.44) | |

| >60 y | 174 | 155 (89) | 19 (11) | 0.64 (0.20 to 2.08) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 229 | 201 (88) | 28 (12) | 0.945 | 1 |

| Female | 217 | 190 (88) | 27 (12) | 1.02 (0.58 to 1.79) | |

| Ethnicity (n = 445)b | |||||

| Caucasian | 375 | 330 (88) | 45 (12) | 0.594 | 1 |

| Non-Caucasian | 70 | 60 (86) | 10 (14) | 1.12 (0.58 to 2.56) | |

| Smoking historyc (n = 440)b | |||||

| Never | 139 | 115 (83) | 24 (17) | 0.030 | 1.89 (1.06 to 3.37) |

| Ever | 301 | 271 (90) | 30 (10) | 1 | |

| Lesion sited | |||||

| Low risk | 178 | 169 (95) | 9 (5) | <0.001 | 1 |

| High risk | 268 | 222 (83) | 46 (17) | 3.89 (1.85 to 8.17) | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Low-grade dysplasia without LM | 373 | 324 (87) | 49 (13) | 0.243 | 1 |

| Low-grade dysplasia with LM | 73 | 67 (92) | 6 (8) | 0.59 (0.24 to 1.44) | |

| Mild dysplasia with or without LM | 252 | 231 (92) | 21 (8) | 0.003 | 1 |

| Moderate dysplasia with or without LM | 194 | 160 (83) | 34 (17) | 2.34 (1.31 to 4.18) | |

| History of lichenoid diagnosis | |||||

| Never | 305 | 267 (86) | 38 (13) | 0.904 | 1 |

| Ever | 141 | 124 (88) | 17 (12) | 2.34 (1.31 to 4.18) | |

| Length of follow-upe | |||||

| Median months of follow-up (range) | 63.8 (7.5 to 258.4) | 68.9 (13.2 to 258.4) | 38.0 (7.5 to 173.2) | <0.001 | |

Values are presented as number (row %) unless otherwise indicated.

CI, confidence interval; LM, lichenoid mucositis; SD, standard deviation.

Progression to severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or squamous cell carcinoma.

One participant declined to provide date of birth, 1 participant declined to provide ethnicity, and 5 participants declined to provide smoking history.

Never smoker, <100 cigarettes in lifetime; ever smoker, consumption of >100 cigarettes in lifetime.

High risk, floor of mouth and tongue; low risk, all other sites.

Months to last follow-up or progression, whichever occurred first.

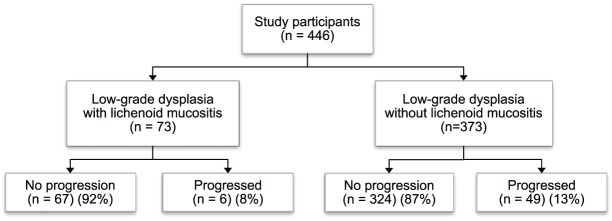

The main objective of the study was to explore whether there were differences in the progression of low-grade dysplasia with LM compared to those with a straightforward diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia without LM. Forty-nine of 373 cases of dysplasia (13%) progressed compared to 8% (6/73) of dysplasia with LM. However, the difference was not statistically different (P = 0.24) (Fig. 1). In addition, there was no significant difference in the risk of progression between low-grade dysplasia that had ever had a diagnosis of LM and those that never possessed lichenoid features (P = 0.90).

Figure 1.

The proportion of malignant progression was similar between low-grade dysplasia with lichenoid mucositis (LM) and those without LM. Forty-nine of 373 cases of low-grade dysplasia (13%) progressed compared to 8% (6/73) of low-grade dysplasia with LM (P = 0.24).

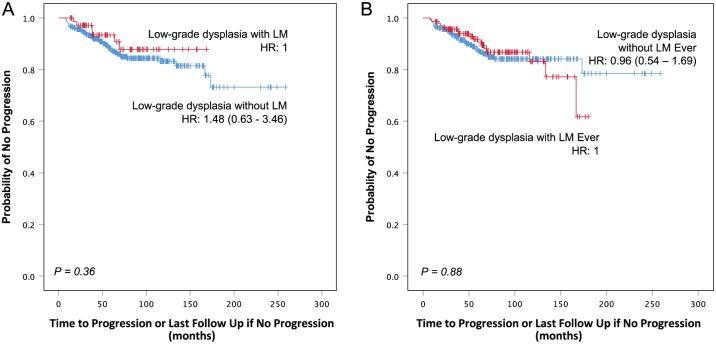

Time to progression did not differ between the groups. Kaplan-Meier plots of progression by histological diagnosis showed very similar plots for the 2 groups of lesions, whether comparing index biopsies (P = 0.36) or whether there was ever a lichenoid diagnosis (P = 0.88) (Fig. 2). Although the 3-y and 5-y probability of progression was higher for low-grade dysplasia without LM (6.7% and 12.5%, respectively) than it was for low-grade dysplasia with LM (2.9% and 6.6%, respectively), it was not significantly different (P = 0.36) (Table 3). The difference was even less for low-grade dysplasia with an ever-lichenoid diagnosis compared to those with a never-lichenoid diagnosis (P = 0.88).

Figure 2.

Low-grade dysplasia with or without lichenoid mucositis possesses a similar cancer risk. (A) Kaplan-Meier plot of time to progression comparing low-grade dysplasia (mild/moderate dysplasia) with lichenoid mucositis (LM) and without LM. Low-grade dysplasia with or without LM had a similar cancer risk (P = 0.36). (B) Kaplan-Meier plot of time to progression comparing low-grade dysplasia with a lichenoid diagnosis ever with low-grade dysplasia without a lichenoid diagnosis ever. Cancer risk in low-grade dysplasia was similar regardless of whether there was ever a lichenoid diagnosis or not (P = 0.88). HR, hazard ratio.

Table 3.

Probability of Progression in Low-Grade Dysplasia with and without Lichenoid Mucositis.

| Characteristic | Total | Low-Grade Dysplasia without LM | Low-Grade Dysplasia with LM | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 446 (100) | 373 (84) | 73 (16) | |

| Months to progressiona (n = 55) | ||||

| Median (range)b | 38.0 (7.5 to 173.2) | 36.3 (7.5 to 173.2) | 38.3 (16.9 to 69.3) | 0.63 |

| Probability of progressiona | ||||

| 3 y (95% CI) | 6.7 (5.4 to 8.0) | 2.9 (0.9 to 4.9) | 0.36 | |

| 5 y (95% CI) | 12.5 (10.6 to 14.4) | 6.6 (3.4 to 9.8) | ||

| Characteristic | Total | Low-Grade Dysplasia without LM Ever | Low-Grade Dysplasia with LM Ever | P Value |

| Total | 446 (100) | 305 (68) | 141 (32) | |

| Months to progressiona (n = 55) | ||||

| Median (range)b | 38.0 (7.5 to 173.2) | 31.8 (7.5 to 173.2) | 42.1 (7.7 to 139.2) | 0.27 |

| Probability of progressiona | ||||

| 3 y (95% CI) | 6.9 (5.4 to 8.4) | 4.4 (2.7 to 6.1) | 0.88 | |

| 5 y (95% CI) | 12.7 (10.6 to 14.8) | 9.4 (6.7 to 12.1) | ||

Values are presented as number (row %) unless otherwise indicated.

CI, confidence interval; LM, lichenoid mucositis.

Progression to severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or squamous cell carcinoma.

Months to last follow-up or progression, whichever occurred first.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that low-grade oral epithelial dysplasia with LM possessed a similar risk of malignant transformation as those without LM. The limitations to the study, like any prospective cohort study, are that it requires a large sample size and long follow-up. This increases the study time, complexity, and cost, as well as the potential of loss to follow-up. Although this study comprised the largest sample size to date to assess the malignant potential of low-grade dysplasia with LM compared to those without LM, there is a possibility of type II error due to lack of sufficient power. However, it is difficult to obtain and follow larger numbers. Another potential limitation is the subjective nature of diagnosis. The critical element that allows separation of low-grade dysplasia with LM from LM or lichen planus is the additional presence of dysplastic features within the overlying epithelium. However, such features are often subtle and subjective, and it is difficult to subclassify various inflammatory disorders accurately—histologic features often overlap one another (Karabulut et al. 1995; Fleskens and Slootweg 2009).

It is well known that heavy inflammation could cause atypical epithelial changes resembling epithelial dysplasia. For this reason, many pathologists tend to discount low-grade epithelial dysplasia when there is heavy inflammation nearby. It is not clear, however, whether these reactive changes are limited to nonspecific inflammation, including acute inflammation from epithelial ulceration and mixed chronic inflammation with plasma cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages that are frequently seen in the oral cavity, such as gingivitis and periodontitis, or include both nonspecific and specific inflammation such as those caused by cell-mediated immunity as seen in LM. It is possible that in the case of LM, one should not discount any dysplasia despite the heavy specific inflammation, which in theory should only attack epithelial cells with antigenicity changes as opposed to nonspecific inflammation, which attacks all nearby cells without discrimination.

One of the dysplastic features as discussed by Krutchkoff and Eisenberg (1985) is prominent basal cells in many of the dysplasias with LM. We have also noted this frequently. It should be emphasized that one of the diagnostic features for LM or lichen planus is destruction or degeneration of basal cell layers since this is the first layer of cells to be attacked by the T lymphocytes in the lamina propria (van der Meij et al. 2003). The presence of prominent basal cells in areas of the lesion despite the heavy inflammation could suggest increased growth ability, a feature for carcinogenesis.

Recognition of dysplasia in the presence of LM is critical for appropriate management of such lesions. As shown in our data, there are no significant differences in cancer progression rate or speed between low-grade dysplasia with or without LM. In our experience in the Oral Biopsy Service, a number of oral cancer patients had dysplastic lesions prior to the oral cancer, but these lesions were misdiagnosed as lichen planus by the pathologists, and the dysplastic changes were discounted because of the inflammation, resulting in mismanagement of the lesions. In 1 case, a large nonhomogeneous leukoplakia in the floor of mouth was diagnosed as lichen planus, even though there was moderate epithelial dysplasia when the slide was reviewed (unpublished data). This lesion later progressed into cancer. As discussed, our previous study had shown that dysplasia with LM had a similar high-risk LOH pattern, supporting the thesis that dysplasia is dysplasia regardless if there is accompanying LM.

In this study, we have shown that low-grade dysplasia with or without LM demonstrated similar cancer risk as judged by cancer progression rate and speed. This is a much higher level of supporting evidence than our previous study, particularly because this study was conducted within the framework of a longitudinal prospective cohort, the OCPL study, the largest longitudinal study attempted to date. It is also unique in that it draws from a community-based rather than a high-risk population, and thus the study results can be considered relevant to the population at large. While this study strongly supports the premise that LM with dysplasia should be regarded as premalignant, it does not rule out the possibility that LM or lichen planus could have a higher chance of becoming dysplasia compared with normal mucosa. The presence of inflammation increases cell proliferation, which in turn may increase the chance of random mutations or replicative errors (Tomasetti and Vogelstein 2015). It is therefore important to follow up these lesions as well.

Conclusion

Low-grade dysplasia with or without LM has a similar cancer risk, and pathologists should not discount the dysplastic changes in the presence of LM. Clinicians should not disregard dysplasia in a pathology diagnosis, even if they believe the patient has lichen planus clinically. Lesions that demonstrate any dysplasia upon biopsy warrant careful follow-up.

Author Contributions

L.D. Rock, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; D.M. Laronde, B. Chan, contributed to data acquisition, critically revised the manuscript; I. Lin, B. Shariati, contributed to analysis and interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; M.P. Rosin, contributed to conception, design, and data interpretation, critically revised the manuscript; L. Zhang, contributed to conception, design, data acquisition, and interpretation, drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the BC Cancer Foundation and grants R01 DE13124 and R01 DE17013 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research. L.D.R. is a recipient of a CIHR Doctoral Research Award (grant 379723) I.L. is a recipient of a University of British Columbia Faculty of Dentistry Summer Research Studentship.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. 2005. Pathology and genetics. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D. editors. Head and neck tumours. Lyon (France): IARC Press; p. 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JB, Wan LS, Gorsky M, Zhang LW. 2003. Oral lichen planus: progress in understanding its malignant potential and the implications for clinical management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 96(1):32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleskens S, Slootweg P. 2009. Grading systems in head and neck dysplasia: their prognostic value, weaknesses and utility. Head Neck Oncol. 1:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut A, Reibel J, Therkildsen MH, Praetorius F, Nielsen HW, Dabelsteen E. 1995. Observer variability in the histologic assessment of oral premalignant lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 24(5):198–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krutchkoff DJ, Eisenberg E. 1985. Lichenoid dysplasia: a distinct histopathologic entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 60(3):308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S, Rao RS, Sanketh DS, Warnakulasuriya S. 2015. Lichenoid dysplasia revisited: evidence from a review of Indian archives. J Oral Pathol Med. 44(7):507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Zhao ZZ, Zhou XJ, Khan A, Seymour GJ, Bigby M. 2002. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 13(4):350–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. 2015. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 347(6217):78–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meij EH, Schepman KP, van der Waal I. 2003. The possible premalignant character of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: a prospective study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 96(2):164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lubpairee T, Laronde DM, Rosin MP. 2016. Should severe epithelial dysplasia be treated? Oral Oncol. 60:125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Michelsen C, Cheng X, Zeng T, Priddy R, Rosin MP. 1997. Molecular analysis of oral lichen planus: a premalignant lesion? Am J Pathol. 151(2):323–327. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Poh CF, Williams M, Laronde DM, Berean K, Gardner PJ, Jiang H, Wu L, Lee JJ, Rosin MP. 2012. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) profiles: validated risk predictors for progression to oral cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 5(9):1081–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LW, Cheng X, Li YH, Poh C, Zeng T, Priddy R, Lovas J, Freedman P, Daley T, Rosin MP. 2000. High frequency of allelic loss in dysplastic lichenoid lesions. Lab Invest. 80(2):233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]