Abstract

Background

Pain control after total knee replacement (TKR) is pivotal in postoperative rehabilitation. Usage of epidural analgesia or parenteral opioids can cause undesirable side effects hampering early recovery and rehabilitation. These side effects can be avoided by infiltration of an analgesic cocktail locally. Our study was performed to evaluate the benefits of a particular cocktail combination in patients undergoing TKR with respect to pain and knee motion recovery.

Methods

One hundred consecutive patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral TKR were enrolled and received an intraoperative periarticular cocktail injection in the right knee (intervention) and normal saline in the left knee (control). Postoperative pain was recorded using the visual analog scale for each knee, and the time taken to achieve 90° of knee flexion was noted for each side.

Results

The cocktail injected knee had significantly less pain when compared with the control knee during the first 48 hours and significantly shorter period to achieve 90° of knee flexion.

Conclusions

The use of intraoperative periarticular cocktail injection significantly reduces early postoperative pain and provides better early knee motion.

Keywords: Total knee replacement, Periarticular, Cocktail injection, Knee flexion, Visual analog scale

Introduction

In patients with advanced knee arthritis, total knee replacement (TKR) has been found to be the most successful surgical procedure. However, early postoperative pain control is pivotal in reducing the hospital stay, increasing patient satisfaction, and for better rehabilitation. It also reduces the potential for postoperative complications such as pneumonia or deep vein thrombosis [1]. Severe postoperative pain is experienced in approximately 60% of the patients and moderate pain in approximately 30% of patients undergoing TKR [2].

Control of pain is achievable through multiple ways, and each has its own risks and benefits. Epidural anesthesia is a common modality for providing effective pain relief during the postoperative period, but it hinders early mobilization and leads to complications such as hypotension, postoperative headache, and spinal infection. Regional nerve blocks pose the risk of injuring neurovascular structures, hematoma formation, and infection [3]. Systemic opioids such as morphine or fentanyl can cause nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, respiratory depression, urinary retention, and constipation [4].

An innovative approach to pain management is to aim at controlling local pain pathways and receptors within the knee. This has been possible through local intraarticular or periarticular injection of analgesic combinations which has good efficacy, is cost-effective, and is easy to administer without causing motor blockade. Also, it does not require any special technical skill for administration [5].

Various studies about periarticular injection have reported promising results from various combinations of drugs such as ketorolac, ropivacaine, bupivacaine, morphine sulfate, epimorphine, methylprednisolone, cefuroxime, epinephrine, and normal saline [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. The patients experienced a prolonged narcotic-free postoperative period and also a reduced parenteral analgesia postoperatively [12], [13].

The present study aims to compare the postoperative pain scores between both the knees of patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral TKR when periarticular cocktail injection was given intraoperatively to the right knee (intervention) and the same volume of normal saline was injected to the left knee (control). By using a particular cocktail combination consisting of bupivacaine, ketorolac, epinephrine, and normal saline, the study also aims at comparing the time (days) taken for both the knees to achieve 90° of active flexion postoperatively. By comparing the pain scores between both the knees of the same patient, confounding factors such as systemic analgesia and variability in patients' tolerability to pain were avoided.

Material and methods

We included patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral TKR from 2015 to 2017 in our institute. For uniformity, we included only the patients for whom spinal anesthesia was the mode of anesthesia. One hundred consecutive patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria were selected for the study. All the patients had a full understanding of the 10-point visual analog pain scale (VAS).

Exclusion criteria were patients with a history of allergy to the medications used in this study, abnormal renal or liver function, uncontrolled diabetes, and those who could not receive spinal anesthesia.

Study protocol

Our study was a prospective, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. All included patients signed an informed consent form, and the methods of this trial were approved by the institutional ethics committee of our institute (institutional ethics committee review no: AM/EC/34-2015).

Intervention

For all the patients, intraoperative periarticular cocktail injection was given to the right knee and the left knee was the control that received a same volume of normal saline (110 mL). The patients were blinded about which knee received the cocktail injection. All the patients received spinal anesthesia with a combination of 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5 mL (25 mg) fentanyl. The antibiotic prophylaxis given was 1.5 g of injection cefuroxime 30 to 40 minutes before incision.

All the operations and the cocktail injections were performed by a single surgeon (first author) using a medial parapatellar arthrotomy approach.

A periarticular cocktail injection consisting of 90 mL of normal saline, 17.5 mL of 5% bupivacaine, 2 mL of inj. ketorolac (30 mg), and 0.5 mL of adrenaline (total volume: 110 mL) was given to the right knee of all the patients involved in the study. The infiltration was performed using a 21-gauge needle and syringe. The aforementioned cocktail injection was formulated by the orthopaedic surgeon based on his or her clinical experience and past clinical studies.

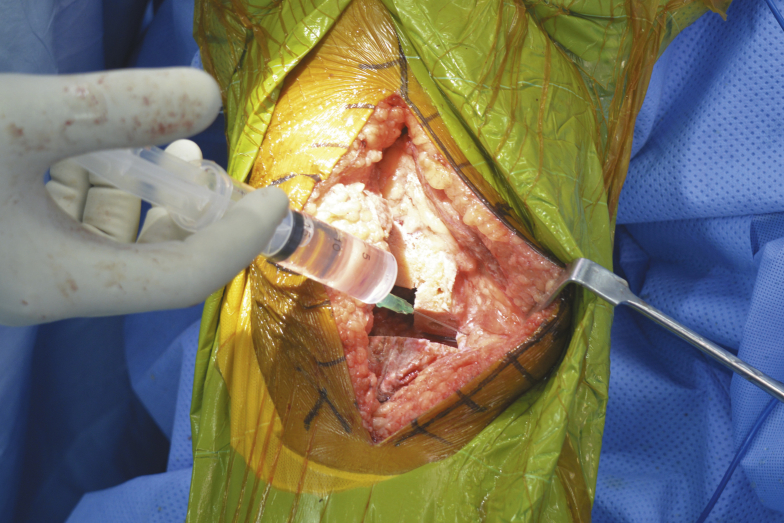

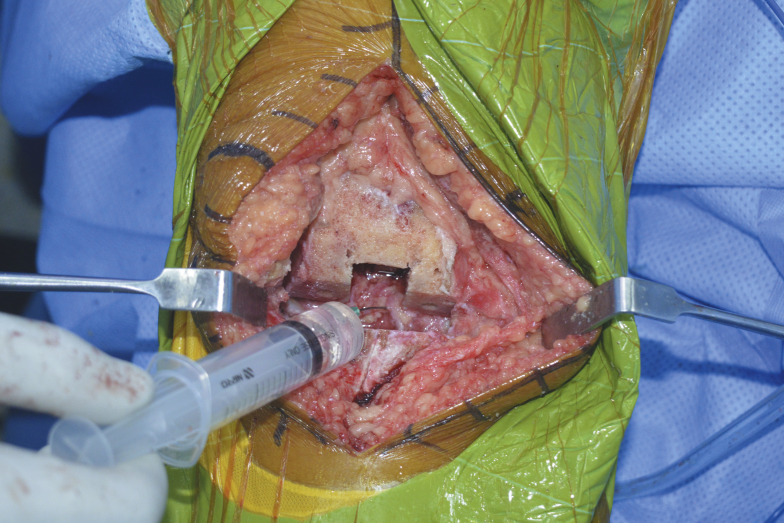

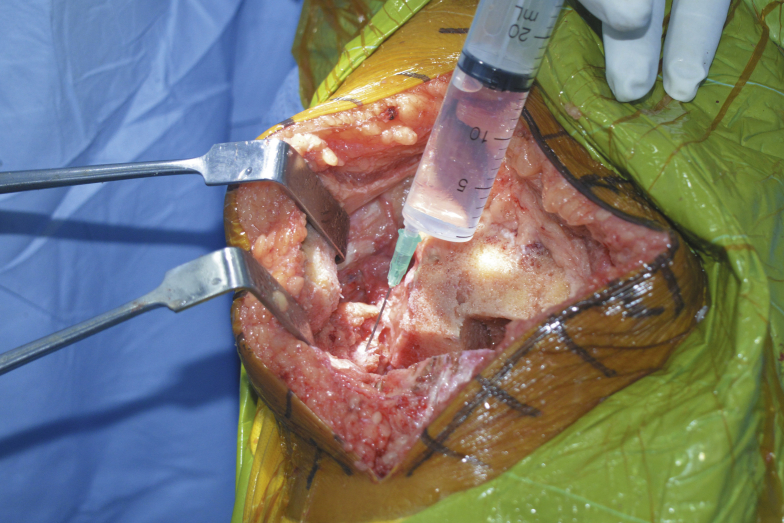

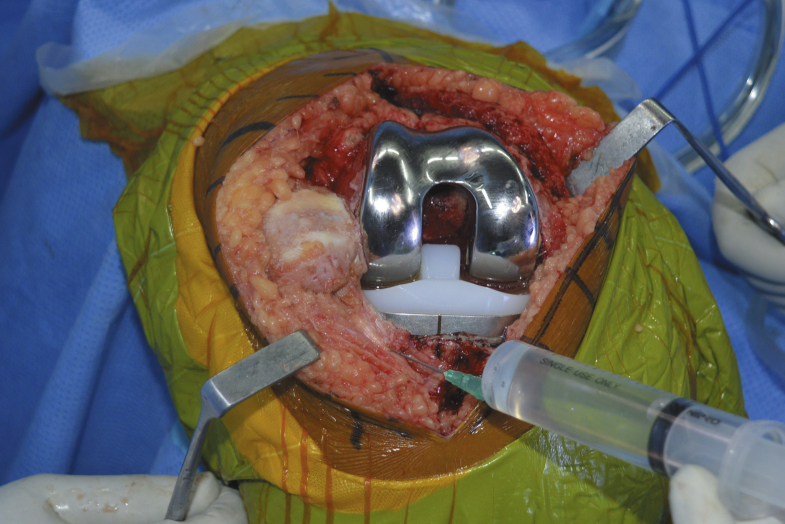

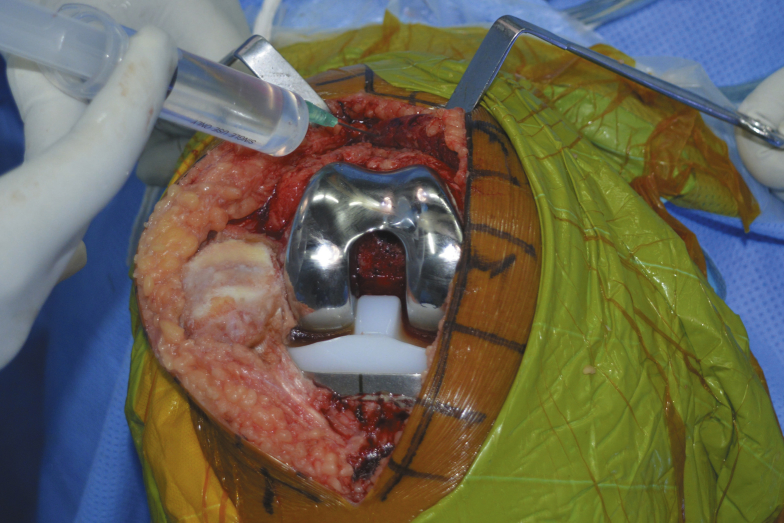

The cocktail was injected at the following 7 anatomical zones [14] as depicted in Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5:

Zone 1: medial retinaculum

Zone 2: medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus capsular attachment

Zone 3: posterior capsule

Zone 4: lateral collateral ligament and lateral meniscus capsular attachment

Zone 5: lateral retinaculum

Zone 6: patellar tendon and fat pad

Zone 7: cut ends of quadriceps muscle and tendon

Figure 1.

Injection of cocktail to medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus capsular attachment.

Figure 2.

Injection of cocktail to lateral collateral ligament and lateral meniscus capsular attachment.

Figure 3.

Injection of cocktail to posterior capsule of knee.

Figure 4.

Injection of cocktail to patellar tendon and patellar fat pad.

Figure 5.

Injection of cocktail to cut ends of quadriceps tendon.

Injection at zones 2, 3, and 4 were administered after making the tibial and femoral cuts and ligament balancing. At zones 1, 5, 6, and 7, the injection was administered after implant placement.

Cemented cruciate-sacrificing implants were used for all the cases. After component placement and cement setting, tourniquet was released, and hemostasis was achieved before the wound was closed. No drains were used.

During the postoperative period, systemic analgesics used were intravenous injection of diclofenac (75 mg) and inj. tramadol (100 mg) along with inj. ondansetron (4 mg) every 12 hours for the first 2 days followed by tablet naproxen 500 mg and tablet tramadol hydrochloride (37.5 mg) with paracetamol (325 mg) for the next 10 days. Buprenorphine patch (10 mg) or oral pregabalin (75 mg) were used in patients for whom the aforementioned medications were insufficient in controlling pain or could not be tolerated.

Apart from mechanical deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis such as DVT stockings, inj. fondaparinux 2.5 mg on the first day followed by oral aspirin 150 mg daily for 6 weeks were given. Patients were mobilized using a walker after 3 to 4 hours of surgery on the same day, and range of motion (ROM) and isometric exercises were started.

All the patients were observed till discharge and are being followed up regularly.

Measurement of outcome

Postoperative pain over both the knees were separately recorded by the nurse, who was blinded about the study, using a 10-point VAS at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours postoperatively, and then, at once-daily intervals till the fourth postoperative day. The VAS consists of a 10-cm line, in which 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates the worst imaginable pain [7], [11], [15].

Postoperative range of active flexion was noted each day till the fourth postoperative day on both the knees separately by the physiotherapist, who was also blinded about the study.

Vitals monitoring included blood pressure, heart rate, and oxygen saturation. Any adverse reactions including allergic reactions, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, or respiratory depression were also monitored till the patients were discharged.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data were tabulated, coded, and analyzed using SPSS, version 17, for Microsoft Windows. Descriptive statistics was reported as mean and standard deviation. Unpaired t test was used to test the statistical association between the intervention arm and control arm. For analyzing the change in pain scores over the same knee during the follow-up periods, we used repeated-measures analysis of variance. A post hoc test was conducted to assess the presence of any statistical significance between the 2 time points.

Results

A total of 100 patients (100 pairs of knees) were included in the study. Osteoarthritis was the underlying condition in 93 patients, while the rest of them had rheumatoid arthritis.

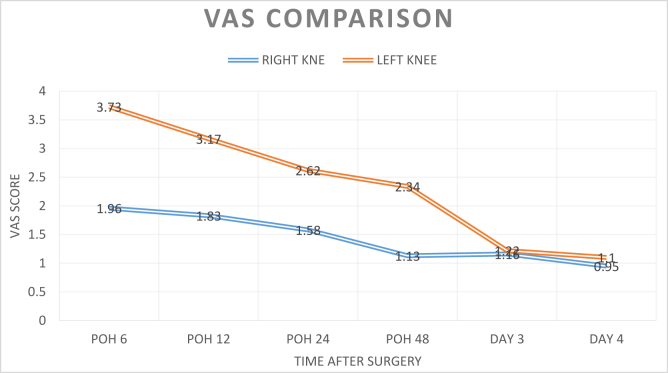

The mean pain scores (VAS) at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours, and at third and fourth days in both knees are enumerated in Table 1 and Figure 6. When compared with the control knee, a statistically significant reduction in pain score was noted in the cocktail injected knee at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours (P < .001 in all cases). However, the difference in the mean pain scores between both knees at the third (P = .684) and fourth (P = .251) days were not significant.

Table 1.

Between-group comparison.

| Postoperative duration | Group | Mean | Standard deviation | Standard error mean | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 h | Control | 3.73 | 1.927 | .193 | <.001a |

| Intervention | 1.96 | 1.406 | .141 | ||

| 12 h | Control | 3.17 | 1.770 | .177 | <.001a |

| Intervention | 1.83 | 1.371 | .137 | ||

| 24 h | Control | 2.62 | 1.362 | .136 | <.001a |

| Intervention | 1.58 | .654 | .065 | ||

| 48 h | Control | 2.34 | 1.056 | .106 | <.001a |

| Intervention | 1.13 | .825 | .082 | ||

| 3 d | Control | 1.22 | 1.050 | .105 | .684 |

| Intervention | 1.16 | 1.032 | .103 | ||

| 4 d | Control | 1.10 | 1.010 | .101 | .251 |

| Intervention | .95 | .821 | .082 |

Significant at P < .05.

Figure 6.

VAS comparison.

The mean time taken for achieving 90° flexion in the intervention and control knees were 1.70 and 2.82 days, respectively. The difference was found to be statistically significant (P < .001).

Within the intervention group, there was a significant difference in the pain scores over different time points (Table 2). A post hoc analysis showed no significant difference within various time points on the first day (6, 12, and 24 hours) after surgery. However, a statistically significant difference in the pain scores was noted at 48 hours (P < .001), 72 hours (P < .010), and 96 hours (P < .001), compared with the 24-hour score.

Table 2.

Within-group repeated-measures ANOVA.

| Group | Mean | Standard deviation | N | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | ||||

| 6 h | 3.73 | 1.927 | 100 | <.001 |

| 12 h | 3.17 | 1.770 | 100 | |

| 24 h | 2.62 | 1.362 | 100 | |

| 48 h | 2.34 | 1.056 | 100 | |

| 3 d | 1.22 | 1.050 | 100 | |

| 4 d | 1.10 | 1.010 | 100 | |

| Intervention | ||||

| 6 h | 1.96 | 1.406 | 100 | <.001 |

| 12 h | 1.83 | 1.371 | 100 | |

| 24 h | 1.58 | .654 | 100 | |

| 48 h | 1.13 | .825 | 100 | |

| 3 d | 1.16 | 1.032 | 100 | |

| 4 d | .95 | .821 | 100 |

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Within the control group, there was a significant difference in pain scores over different time points (Table 2). However, a post hoc analysis showed that there was no significant difference within various time points on the first day (6, 12, and 24 hours) after surgery, and statistically significant improvement was found only after 72 hours (P < .001) and 96 hours (P < .001), compared with the 24-hour value.

Discussion

During TKR, trauma to the tissues exaggerates the neurological responsiveness to pain by reducing the threshold of afferent nociceptive neurons and by central sensitization of excitatory neurons. This contributes to increased sensitivity to postoperative pain [11]. Hence, a multimodal approach for postoperative pain control has been particularly effective not only in relieving postoperative pain but also in facilitating earlier rehabilitation and improving postoperative ROM. It also reduces the complications of other modalities of pain management such as patient-controlled anesthesia (PCA), continuous epidural anesthesia, and femoral nerve block [2], [11], [16].

The rationale for using the analgesic cocktail was to facilitate contraction of the smooth muscles that line the arterioles to potentially minimize intraarticular bleeding and prolong the time the agents would act locally. The component epinephrine in the cocktail is especially conspicuous in this regard [3], [5], [11], [17].

The component ketorolac not only acts as antiinflammatory and analgesic but also possesses synergistic activity when given along with other oral nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, such as acetaminophen and gabapentin, thereby reducing the requirement of these systemic agents [5]. Significant pain relief was obtained when intraarticular ketorolac was given along with bupivacaine and epinephrine as a cocktail combination in previous studies [3], [11], [17].

According to Badner et al. [15], addition of an opioid like morphine in the cocktail mixture did not provide any significant additional advantage when compared to cocktail mixtures without opioids with respect to postoperative pain relief [18]. In accordance with their study, our study also excluded the use of opioids in the cocktail mixture.

According to Christensen et al. [19], addition of steroids to multimodal periarticular cocktail injection only minimized the length of hospital stay in patients undergoing TKR. It did not improve pain relief or early postoperative ROM. They also posed an increased risk of postoperative infection [12], [19]. Although the existing randomized controlled trials have confirmed the safety of steroids, many surgeons still hesitate to use a drug which is thought to increase the risk of catastrophic complications such as infection and patellar tendon rupture [15], [20], [21], [22]. For the aforementioned reasons, steroids were not added to the cocktail mixture in our study.

The results of immediate postoperative pain control by various authors are promising. Mullaji et al. [23] used bupivacaine, fentanyl, methylprednisolone, and cefuroxime in their intraarticular cocktail. Badner et al. [15] used a combination of bupivacaine and epinephrine. Andersen et al. [24] used subcutaneous ropivacaine, and Vaishya et al. [25] used bupivacaine, adrenaline, morphine, ketorolac, and gentamycin. All of them demonstrated significant pain relief, increased early postoperative knee movements, and quadriceps function.

Since our study compared the results of each knee of the same patient, the physical therapy regime and systemic medications (including antiinflammatories, analgesics, and antibiotics) would be the same for each knee of a particular patient, thereby eliminating these confounding factors during the comparison. Even though a power analysis was not performed before commencing the study, the number of knees included in our comparison (100 patients with 200 knees) was higher compared with the previous similar studies [2], [3], [4], [26]. We included consecutive bilateral TKR patients belonging to a particular time frame.

In our study, the cocktail injection was given in a periarticular manner. Significant reduction in pain (by VAS) was recorded over the knee where the injection was given (right side) compared with the opposite side at 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours (P < .001). This is in comparison with the study by Fu et al. [2] which showed VAS score at rest was significantly lower at 6, 10, 24, and 36 hours postoperatively in the trial group compared with the control group, although the difference was insignificant at 24 hours postoperatively, and at days 2, 7, and 15 between the 2 groups. VAS score during activity was also lower in the trial group at 24 and 36 hours postoperatively than that in the control group, although the difference was insignificant at days 2, 7, and 15 [2], [8]. Busch et al. noted that patients who received a periarticular intraoperative injection containing ropivacaine, ketorolac, epimorphine, and epinephrine used significantly less PCA during the first 24 hours postoperatively [11]. Vaishya et al. [25], in their study comparing 2 groups of 40 knees each, reported that the cocktail injected patients reported significantly less PCA and postoperative pain recordings at 6, 24, 48, and 72 hours after TKR.

In our study, the time taken to achieve 90° of knee flexion postoperatively was found to be significantly longer for the control side (mean 2.82 days) than that for the intervention side (mean 1.70 days). According to a comparative study by Rasmussen et al., use of 24- to 72-hour continuous intraarticular infusion of morphine plus ropivacaine showed a significant improvement in ROM and decreased the length of hospital stay [27]. According to the study by Fu et al., in which 80 patients were grouped into 2 groups namely trial and control, the time of being able to perform straight leg raise and reaching 90° knee flexion was significantly shorter in the trial group than that in the control group. The mean ROM at day 15 was greater in the trial group than the control group, and the difference was insignificant at day 90 between the 2 groups, indicating that intraarticular analgesic injection is helpful in early postoperative rehabilitation [2].

Regarding the method of injection, according to Dalury [5], the goal is to deliver as much of the fluid as possible into the tissues, where it will be most effective. Using smaller needles, such as 22 gauge, is the best choice, and using control syringes (that allow for aspiration before injection and are more comfortable for the hand) are helpful when injecting areas of potential danger [5]. In our study, we used a 21-gauge needle and a 20-mL conventional syringe for each knee.

Regarding the anatomical zones of injection, we injected the cocktail to the 7 zones as already mentioned which was similar to that of George et al. [14]. The only differences are that anterior cruciate ligament and posterior cruciate ligament attachment sites were not included for injection since we used cruciate-sacrificing type of implants. Cocktail injection to the cut ends of quadriceps tendon was given in addition.

In a study conducted by Nakai et al. [26], postoperative nausea and vomiting was the least observed complication in the periarticular injection group compared with the other 2 groups where no injection or intraarticular injection was used. Femoral nerve blocks and epidural anesthesia have been reported to control pain with good efficacy. However, these procedures require a well-trained physician, and there are some complications that could result from these procedures. Sharma et al. [28] reported the rate of femoral neuropathy after femoral nerve block to be approximately 0.59%. Vendittoli et al. [7] reported that periarticular infiltration with ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline on the first postoperative day showed a reduction in narcotic requirements at 48 hours after the operation with minimal side effects when compared with the control group [7]. In our study, 1 patient in the intervention group developed postoperative infection, followed by loosening. Two-staged revision was performed after the infection was controlled. Delayed wound healing characterized by bloody and serous discharge was encountered in 2 patients over the right side (intervention group) and 3 patients over the left side (control group). Their swabs were culture negative, and their wounds healed well on repeated cleaning and dressing. There were no cases of hematoma formation clinically in either group. None of the patients included in the study incurred symptomatic DVT, and there were no cases of allergic reactions.

There are a few limitations in our study. A power analysis was not performed before commencing the study, and we just included patients belonging to a particular time frame. The optimal concentration of the individual components of the cocktail could not be determined, and further effort is required to comment on the superiority of 1 component over the other. Another question of debate is whether the infiltration of normal saline to the control side itself could incite pain mechanically even though we presumed normal saline by itself has no local pharmacological effects. Our study did not attempt at evaluating long-term clinical outcomes of the patients.

Conclusions

The results of our study clearly show that periarticular cocktail injection in TKR not only helps in relieving the pain but also aids in early recovery and rehabilitation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Venkitachalam R for assistance with statistical analysis and all other staff members of the Department of Orthopaedics, Aster Medcity Hospital, for their support.

Footnotes

No author associated with this paper has disclosed any potential or pertinent conflicts which may be perceived to have impending conflict with this work. For full disclosure statements refer to https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artd.2019.05.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.Galimba J. Promoting the use of periarticular multimodal drug injection for total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Nurs. 2009;28(5):250. doi: 10.1097/NOR.0b013e3181b822ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu P., Wu Y., Wu H., Li X., Qian Q., Zhu Y. Efficacy of intra-articular cocktail analgesic injection in total knee arthroplasty—a randomized controlled trial. Knee. 2009;16(4):280. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fajardo M., Collins J., Landa J., Adler E., Meere P., Di Cesare P.E. Effect of a perioperative intra-articular injection on pain control and early range of motion following bilateral TKA. Orthopedics. 2011;34(5):e33. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20110317-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuenyongviwat V., Pornrattanamaneewong C., Chinachoti T., Chareancholvanich K. Periarticular injection with bupivacaine for postoperative pain control in total knee replacement: a prospective randomized double-blind controlled trial. Adv Orthop. 2012;2012:107309. doi: 10.1155/2012/107309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalury D.F. A state-of-the-art pain protocol for total knee replacement. Arthroplasty Today. 2016;2(1):23. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toftdahl K., Nikolajsen L., Haraldsted V., Madsen F., Tønnesen E.K., Søballe K. Comparison of peri-and intraarticular analgesia with femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized clinical trial. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(2):172. doi: 10.1080/17453670710013645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vendittoli P.A., Makinen P., Drolet P. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):282. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parvataneni H.K., Shah V.P., Howard H., Cole N., Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. Controlling pain after total hip and knee arthroplasty using a multimodal protocol with local periarticular injections: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(6):33. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maheshwari A.V., Blum Y.C., Shekhar L., Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. Multimodal pain management after total hip and knee arthroplasty at the Ranawat Orthopaedic Center. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1418. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0728-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranawat A.S., Ranawat C.S. Pain management and accelerated rehabilitation for total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(7):12. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Busch C.A., Shore B.J., Bhandari R. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):959. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez-Palazon J. Infiltration of the surgical wound with local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia in patients operated on for lumbar disc herniation. Comparative study of ropivacaine and bupivacaine. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2001;48(1):17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherian M.N., Mathews M.P., Chandy M.J. Local wound infiltration with bupivacaine in lumbar laminectomy. Surg Neurol. 1997;47(2):120. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galindo R.P., Marino J., Cushner F.D., Scuderi G.R. Periarticular regional analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: a review of the neuroanatomy and injection technique. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badner N.H., Bourne R.B., Rorabeck C.H., MacDonald S.J., Doyle J.A. Intra-articular injection of bupivacaine in knee-replacement operations. Results of use for analgesia and for preemptive blockade. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(5):734. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199605000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng F.Y., Ng J.K., Chiu K.Y., Yan C.H., Chan C.W. Multimodal periarticular injection vs continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, crossover, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(6):1234. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelley T.C., Adams M.J., Mulliken B.D., Dalury D.F. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1274. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritter M.A., Koehler M., Keating E.M., Faris P.M., Meding J.B. Intra-articular morphine and/or bupivacaine after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(2):301. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.9110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen C.P., Jacobs C.A., Jennings H.R. Effect of periarticular corticosteroid injections during total knee arthroplasty: a double-blind randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(11):2550. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sauerland S., Nagelschmidt M., Mallmann P., Neugebauer E.A. Risks and benefits of preoperative high dose methylprednisolone in surgical patients. Drug Saf. 2000;23(5):449. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200023050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilron I. Corticosteroids in postoperative pain management: future research directions for a multifaceted therapy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48(10):1221. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2004.00581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J.J., Ho S.T., Lee S.C., Tang J.J., Liaw W.J. Intraarticular triamcinolone acetonide for pain control after arthroscopic knee surgery. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(5):1113. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199811000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mullaji A., Kanna R., Shetty G.M., Chavda V., Singh D.P. Efficacy of periarticular injection of bupivacaine, fentanyl, and methylprednisolone in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(6):851. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen L.Ø., Husted H., Kristensen B.B., Otte K.S., Gaarn-Larsen L., Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of subcutaneous local anaesthetic wound infiltration in bilateral knee arthroplasty: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54(5):543. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaishya R., Wani A.M., Vijay V. Local infiltration analgesia reduces pain and hospital stay after primary TKA: randomized controlled double blind trial. Acta Orthop Belg. 2015;81(4):720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakai T., Tamaki M., Nakamura T., Nakai T., Onishi A., Hashimoto K. Controlling pain after total knee arthroplasty using a multimodal protocol with local periarticular injections. J Orthop. 2013;10(2):92. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen S., Kramhøft M., Sperling K., Pedersen J. Increased flexion and reduced hospital stay with continuous intraarticular morphine and ropivacaine after primary total knee replacement Open intervention study of efficacy and safety in 154 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2004;75(5):606. doi: 10.1080/00016470410001501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma S., Iorio R., Specht L.M., Davies-Lepie S., Healy W.L. Complications of femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):135. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1025-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.