Abstract

Objectives:

To conceptualize the pathways and assess current evidence for the relationship between caregiver well-being and the quality of the cancer patient’s care.

Data sources:

Qualitative, quantitative, and theoretical literature and official reports.

Conclusion:

Caregiver well-being has both direct and indirect effects on the quality of cancer care, including care received from the healthcare team, from the caregiver themselves, and in relation to patients’ own self-management.

Implications for Nursing Practice:

Supporting caregivers has tangible consequences with regard to the quality of cancer care on multiple levels, with direct implications for patient outcomes. Nurses have a key role in providing psychosocial care to patients and their caregivers, and in supporting system-level change.

Keywords: Caregiver, Caregiving, Well-Being, Care Quality, Cancer

Introduction

Care quality is a critical issue for cancer patients and healthcare delivery systems. As a complex illness, cancer treatments, costs, access to clinical trials, and other factors vary immensely from patient to patient and practice to practice, even among those with the same diagnosis and stage of disease.1 Disparities in cancer care and associated outcomes, as well as escalating costs have led to an increasing focus on care quality.

One under-studied factor that may contribute to cancer care quality is the presence and well-being of a caregiver. Caregivers provide a multitude of supportive functions for cancer patients, including emotional, informational, and functional support as well as, increasingly, practical assistance with skilled care activities (e.g., tube feeding, dressing changes). When caregivers experience physical or emotional challenges, it is reasonable to expect that they will be less capable, competent, and confident at providing such care. In their 2013 report on cancer care quality, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) highlighted support for caregivers as a critical component in high quality care across the cancer continuum,1 and the involvement of family and friends is considered a dimension of patient-centered care.2

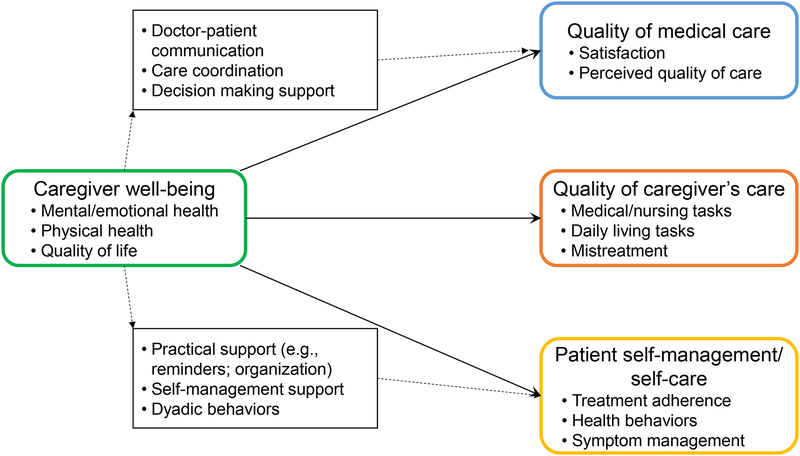

The purpose of this article is to conceptualize the role of the caregiver in supporting high quality cancer care and assess the state of the research evidence. Quality of care is here conceptualized not only as the care provided by the healthcare team, but also the care provided directly by the caregiver and the patient’s own self-care and self-management activities. In particular, potential pathways by which the caregiver’s well-being may impact care quality across the patient-provider-caregiver triad are considered. The article is organized around a conceptual model (Figure 1) highlighting several potential mechanisms and pathways. Given the relative paucity of studies examining the link between caregiver well-being and care quality in the cancer context, this article draws on studies across health conditions to understand how caregiver well-being can influence care quality.

Figure 1. Conceptual model of the relationships between caregiver well-being and care quality.

Caregiver well-being is conceptualized as influencing care quality on three levels: the direct effect of caregiver well-being on their own ability to provide patient care; the indirect effect on the care provided by the medical team through the caregiver’s role in supporting patient-provider communication, care coordination, and decision making; and the effects on the cancer patient’s own self-management and self-care through the caregivers’ ability to provide practical support, self-management support, and engage in dyadic health-promotion activities.

What is Care Quality?

Care quality has been defined as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge,”3 specifically care that is safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.2 In the context of cancer care, this includes not only evidence-based treatment and appropriate care coordination, but also the monitoring and treatment of symptoms and side effects, palliative care throughout the cancer trajectory, and a focus on psychosocial needs.4

Quality of care is often contextualized in terms of medical care, i.e., care received by doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals on the healthcare team. However, caregivers provide an increasing amount of medical care to cancer patients. In addition to attending medical appointments (73% of caregivers), cancer caregivers commonly report keeping track of side effects (68%), helping to manage or control symptoms (47%), and administering medicine (34%), among other medical tasks.5 Furthermore, many cancer caregivers engage in complex medical or nursing tasks such as administering intravenous infusions, managing mechanical ventilators, or providing tube feeding.6 In addition, patients play a critical role in their own medical care, from taking their medications on time and reporting symptoms and side effects to engaging in health practices that may enhance their treatment, decrease side effects, or improve quality of life. Caregiver-provided care and patient self-management can therefore influence the outcomes of care (both subjective outcomes such as patient experience or satisfaction, and objective outcomes such as morbidity and mortality) and the process of care (such as timely receipt of treatment and patient-provider communication).7 Thus, quality of care provided by the healthcare team, the care provided by the caregiver, and the cancer patient’s own self-management can be considered as part of the context of care quality.

Quality of Care Provided by the Medical Team

The simple presence of a family member or friend at a medical visit (referred to as a “companion”) has been linked with quality measures. For example, when families were involved in their care, Medicaid beneficiaries were less likely to be hospitalized or go to the ER and had fewer health problems.8 In the primary care setting, patients who were accompanied to their visit reported better satisfaction with their physician’s technical skills, information giving, and interpersonal skills than those who were unaccompanied, particularly when the companion was more active in the appointment9 (although other studies have reported a null association – for a review see Laidsaar-Powell et al.10). In the cancer context, married patients had less delay in initiating adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer,11 indicating a potential role for the patient’s family and caregiving situation in determining clinical outcomes and quality metrics.

Less research has examined how caregiver well-being is associated with the quality of healthcare, particularly in the context of cancer. Early work in a small, cross-sectional sample of advanced stage cancer patients indicated that caregivers’ levels of satisfaction and depressed mood were associated with their reports of the quality of care provided to the patient.12 Further research in a large, multi-site sample of lung and colorectal cancer patients showed that caregiver health was associated with the patient’s own reports of their health care. Specifically, when their caregiver reported poor self-rated health, cancer patients were nearly four times more likely to report receiving poor quality health care.13 Caregiver depressive symptoms were also associated with worse patient-reported medical care quality.13 Interventions that support caregivers – e.g., discharge planning interventions – have also been shown to improve quality metrics such as hospital readmission rates,14,15 and it has been suggested that interventions to reduce distress of cancer caregivers may have the potential reduce patients’ hospital re-admissions or interruptions in cancer treatment cycles.16

How might caregivers contribute to the quality of medical care? Several potential pathways are depicted in Figure 1. First, caregivers and companions play a clear role in healthcare appointments. Research by Wolff, et al. consistently shows that in the primary care setting, older adults are often accompanied to medical appointments and these companions play a key role in facilitating patient-provider communication and information transfer.9,17,18 In routine medical visits, the majority of companions (64%) helped with communication tasks such as recording physician comments and instructions, communicating information about the care recipient’s medical condition, and asking questions.9 More than half of companion communication behaviors were directed at improving doctor understanding of the patient’s concerns.17

Although there is less cancer-specific research in this area, both qualitative and quantitative studies confirm the key role of cancer caregivers in facilitating communication at healthcare appointments. In particular, cancer patients and their companions appear to play complementary communication roles during healthcare appointments. Patients and their companions supplement each other’s recall of the information shared at the oncology appointment – dyads together had better pooled information recall scores than either patients or their companions alone, or unaccompanied patients19 – and companions’ active participation in oncology appointments is associated with greater patient-centered communication from the physician.20 This reflects the lived experience of cancer patients: the majority of cancer patients have a “key” family member who attends most of their appointments and acts as a team to help the patient obtain, understand, and remember information.21

Second, caregivers have a well-recognized role in coordinating care.6 Caregivers often schedule and coordinate appointments, communicate with insurance companies, and ensure the flow of information between providers.22–25 Given the fragmentation across medical specialties1 and the prevalence of multimorbidity among cancer patients,26,27 it is not surprising that the majority of caregivers play some role in health systems logistics or care coordination activities.24 One study of primary care visits indicated that more than half of caregivers’ behaviors during healthcare appointments were clarifying and expanding on the patient’s medical information and history.17 Cancer caregivers report difficulty coordinating care across different professionals28 and health systems logistics (e.g., scheduling and coordinating appointments) are a source of burden for caregivers.28,29 Caregiver who are unwell or burnt out may have less capacity to fill this role, which may both amplify their burden and adversely impact care quality.

Finally, caregivers and companions play a role in decision making. The majority of companions of cancer patients (up to 88%) report being involved in the decision making process.30 Caregiver roles in decision making include information-gathering, emotional support, advocacy, and deliberation support (e.g., playing ‘devil’s advocate’), among others.30,31 Not only do patients appreciate the caregiver’s contribution to decision making,31 physicians also report that decision-making is facilitated when the patient is accompanied to the oncology appointment by a caregiver or companion.32 Cancer caregivers’ roles in decision making are seen to be variable over time and across decision situations, and are influenced by numerous patient and dyadic factors including the patient’s decision-making capacity and the caregiver’s involvement in the daily management of the illness.33 Caregivers who experience stress, burden, or physical health problems may not have the emotional or cognitive capacity to participate in decision-making.34

In addition to the evidence summarized above, the impact of caregiver well-being can also be inferred from laboratory studies and research in the general population. Caregivers – particularly those with high levels of stress or burden – are at increased risk of mental health problems (e.g., depression and anxiety), exhaustion and fatigue, poor sleep, pain, and chronic health conditions, among other challenges.28,35,36 There is considerable evidence that these components of a caregiver’s well-being are linked with decrements in performance outcomes such as memory, cognitive capacity, decision making ability, and executive function. Stress has been associated with various performance outcomes including attention, memory, judgement, and decision-making;37,38 pain and poor sleep have been linked with executive function, memory, and emotion control.39–41 Although apparently unstudied in cancer caregivers, stress and depression have been associated with impairments in cognitive function, attention, and executive function among caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease.42,43 These deficits have direct implications for caregivers’ ability to provide direct care and facilitate the care of healthcare professionals: when caregivers cannot remember important information, struggle with attention or accuracy, or experience other cognitive and executive function deficits due to the stress or physical and emotional repercussions of their caregiving role, they are less able to facilitate communication with clinicians, coordinate care, assist with decision making, and provide high quality direct care to the cancer patient.

Quality of Care Provided by the Caregiver

The care provided by the caregiver is a critical component of overall care quality, in light of the medical and non-medical supports provided directly by the caregiver. As others have observed (e.g., Schulz and Tompkins44), the compromised health status of chronically stressed caregivers likely diminishes their capacity to provide care. For example, caregivers who experience injuries, age-related mobility changes, or health conditions may be less physically able to provide high-quality care to the patient, and mental, emotional, or quality of life challenges, including burnout and feelings of overwhelm, may impact caregivers’ capacity to juggle their multiple roles and provide care. Little research has explored the impact of caregiver well-being on their own performance and capacity to provide care. However, there are indications that caregiver well-being is linked with care quality: in one population-based study, care recipients were more likely to have unmet needs (e.g., going without bathing, going without groceries) when their caregiver had physical health limitations or high levels of stress.45 Additionally, both caregiver functional ability and depressive symptoms have been associated with risk of maltreatment among older adults.46,47

As noted above, there is clear evidence that stress and poor physical and mental health have adverse impacts on performance ranging from attention and memory to cognition and decision making,37–41 all of which are critical elements in a caregiver’s ability to provide high-quality care. Furthermore, poor health including depression, burnout, and fatigue have been linked with medical errors in healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses;48 medical residents;49 physicians50). Given the increasing amounts of medical care and nursing tasks for which caregivers are responsible, it is reasonable to anticipate similar consequences of the caregivers’ well-being on the quality of care they provide at home. More research is needed, however, to understand how caregiver well-being influences the capacity and performance of cancer caregivers.

Quality of the Patient’s Self-management and Self-care

Cancer patients have several self-management responsibilities that impact their care outcomes, such as: daily treatment regimens; tracking, reporting, and managing side effects and symptoms; and proactive help-seeking.51 Furthermore, self-care behaviors such as exercise and diet play a role in patients’ quality of life41,52 and may even enhance the efficacy of some cancer treatments53,54 or reduce their side effects.55,56 Thus, patients have a role in their own medical outcomes and care quality.

The role for caregivers in patients’ self-management is also clear. A 2004 meta-analysis provided strong evidence that patients who received practical support (e.g., assistance, reminders, organization) were more likely to be adherent to their treatment; there was also evidence of a weaker association between emotional support and adherence.57 Caregivers may therefore play a role both in motivating patients to adhere to their treatments and facilitating their ability to do so. Among heart failure patients, those who were accompanied to their appointments had better self-care management (i.e., decision making in response to symptoms) and self-care maintenance (e.g., adherence to medications),58 and family functioning was associated with greater self-care confidence and motivation for adherence.59 In the cancer context, support from family and friends has been associated with shorter patient-related delay in seeking treatment (i.e., short time from the onset of symptoms to the first medical visit).60

Furthermore, there is evidence that individuals are more likely to make a positive health behavior change if their partner does too.61 Indeed, one national study indicated that cancer survivors with a caregiver were more likely to report that cancer led them to develop healthier habits compared to survivors without a caregiver.62 Thus, caregivers may also have a direct role in supporting the self-care behaviors of the cancer patient by improving their own health behaviors. Caregivers who are in good physical and emotional health are likely best able to provide practical, emotional, and self-management support to the cancer patient; however, research directly examining the impact of caregiver well-being on patient self-care and self-management is lacking.

Implications

Despite widespread recognition that the impact of cancer extends beyond the patient, there is a continued need to enhance healthcare systems’ ability to provide support to caregivers. Caregivers continue to report feeling invisible or even dismissed in clinical encounters63,64 and have unmet needs that range from information about the cancer to dealing with their own emotional distress.65 Up to half of cancer caregivers report not getting needed training for the care they provide (e.g., administering medication; managing symptoms and side effects) and more than a quarter lack confidence in the quality of care they provide at home.5

The emerging understanding of the role of the caregiver’s well-being in the quality of their patient’s cancer care has several direct implications for clinical practice and health systems, and nurses are critical for supporting these efforts (Table 1). Nurses have a front-line role in supporting cancer patients and their families and caregivers and ensuring the delivery of high-quality care,66 and psychosocial care is an integral part of their role.67 Evidence-based strategies that nurses may be well-placed to employ include psycho-educational, cognitive behavioral and supportive interventions.68 Nurses should recognize that the real-time psychosocial care they provide may augment not only the well-being of a caregiver, but also the quality of care and patient outcomes.

Table 1.

Implications for Nursing Practice

| Implication | Potential Role for Nurses |

|---|---|

| Ongoing, informal caregiver support | Continue providing real-time psychosocial care and referral to medical and non-medical resources, especially using evidence-based strategies.68 |

| Systematic assessment of caregiver well-being and needs | Utilize rapport with caregivers to facilitate well-being screening and needs; utilize healthcare system and quality knowledge to ensure follow-through with appropriate referrals and resources |

| Caregiver training | Provide caregivers with training in the medical and nursing tasks they will be expected to conduct at home; check in about confidence/competence at subsequent visits |

| Assess patient preferences for family involvement | Facilitate ongoing conversation and document family involvement preferences |

| Development, evaluation, and dissemination of clinical strategies | Engage in developing and refining workable strategies for systematic caregiver support; promote successful approaches |

| Development of system-level support and strategies for caregiver support | Identify and escalate needs and challenges around supporting family caregivers (e.g., work flow issues that limit integration of screening or training into daily clinical practice; need for protocols or standards) |

The frequent contact, accessibility, and rapport that nurses have with patients and caregivers are critical resources in efforts to enhance systematic support for caregivers. As nurses develop a rapport with patients and families, caregivers may speak more openly and honestly about their challenges, struggles, and needs. In addition to providing real-time opportunities to deliver psychosocial care, this communication may facilitate caregiver assessment and screening, non-medical referrals such as housing and transportation assistance, training caregivers on the medical or nursing tasks that they will undertake at home, and referrals to more formal mental health care. Furthermore, nurses are in a position to engage patients and families in an on-going conversation about preferences around family involvement, which may ebb and flow over time as a function of patient health, decision-making capacity, family situation, and other factors.31

Moving towards a stronger family-centered care model will also be critical for providing adequate support for caregivers,69,70 and will require both provider and systems-level efforts. There is a strong need to develop, evaluate, and disseminate clinical strategies and best practices for supporting caregivers. Emerging models of psychosocial services provision offer a template for this approach,71 as do evidence-based caregiver needs assessment tools (e.g., Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool [CSNAT]72). However, these have yet to be widely enacted.69 In particular, evaluation and dissemination of successful, innovative strategies that are emerging ad hoc in individual clinics and systems will be critical for developing and disseminating best practices. Systems and procedures – including making use of electronic health records, checklists, and other tools that are currently a part of the clinical workflow, as well as incorporating caregivers into survivorship care plans – will be needed to embed family-centered care in clinical practice.

Improving family-centered care will also require healthcare system changes and explicit support for these practices, in the form of funding, recognition, and policy changes. Collaborative care that extends to addressing family and caregiver needs has the potential to improve quality of care and health outcomes on the individual, family, and population levels. Nurses have a key role in facilitating systems change by identifying and escalating priority issues and challenges and providing on-the-ground feedback about the usability and effectiveness of protocols, gaps in implementation or follow-through, and other big-picture quality concerns.

It should be noted that the conceptual model offered here represents only one set of potential mechanisms and pathways, rather than an exhaustive inventory. It is expected that additional pathways will be hypothesized and tested as this literature grows. Importantly, the interrelationships among the caregiver, patient, and healthcare system are likely bi-directional or cyclical, with poor quality care and poor patient self-management potentially adversely influencing caregiver well-being and capacity. Thus the implications of this work extend to the need to better understand these interrelationships in order to develop effective, evidence-based family-centered care that supports both patients and their caregivers.

Conclusions

Caregiver well-being has implications for the quality of cancer care provided by the healthcare team; the care provided by the caregiver themselves; and the caregiver’s ability to support cancer patients’ own self-management and self-care. Given the mounting evidence for the impact of caregiver well-being on cancer care quality, supporting caregivers is a clinical imperative. Nurses have a key role in supporting caregiver well-being in light of their frequent contact with cancer patients and families, and aptitude in providing psychosocial care. Robust clinical strategies and systems-level change will be necessary to support nurses and other clinicians in their continued provision of psychosocial care to patients, families, and caregivers.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Kris Kwekkeboom for her feedback.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Care Services, Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz P, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine, Committee to Design a Strategy for Quality Review and Assurance in Medicare Lohr KN, ed. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance, Volume 1 Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. Quality Cancer Care. https://www.canceradvocacy.org/cancer-policy/quality-cancer-care/ ; n.d. Accessed February 2, 2019.

- 5.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, et al. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: A hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reinhard SC, Levine C, Samis S. Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care. Washington DC: AARP Public Policy Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donabedian A Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3):Suppl:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coe NB, Guo J, Konetzka RT, Van Houtven CH. What is the marginal benefit of payment‐induced family care? Impact on Medicaid spending and health of care recipients. Health Econ. 2019; March epub ahead of print. 1–15. doi: 10.1002/hec.3873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Hidden in plain sight: Medical visit companions as a resource for vulnerable older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1409–1415. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laidsaar-Powell RC, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: A systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(1):3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malietzis G, Mughal A, Currie AC, et al. Factors implicated for delay of adjuvant chemotherapy in colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(12):3793–3802. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4479-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleming DA, Sheppard VB, Mangan PA, et al. Caregiving at the end of life: Perceptions of health care quality and quality of life among patients and caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(5):407–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, Rowland JH. How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? Exploring associations and pathways. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(29):3554–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang TT, Liang SH. A randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of a discharge planning intervention in hospitalized elders with hip fracture due to falling. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(10):1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281(7):613–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Given B, Sherwood PR. Family care for the older person with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2006;22(1):43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolff JL, Guan Y, Boyd CM, et al. Examining the context and helpfulness of family companion contributions to older adults’ primary care visits. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(3):487–494. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansen J, van Weert JC, Wijngaards-de Meij L, van Dulmen S, Heeren TJ, Bensing JM. The role of companions in aiding older cancer patients to recall medical information. Psychooncology. 2010;19(2):170–179. doi: 10.1002/pon.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Street RL, Gordon HS. Companion participation in cancer consultations. Psychooncology. 2008;17(3):244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, Fisher A, Juraskova I. Attitudes and experiences of family involvement in cancer consultations: A qualitative exploration of patient and family member perspectives. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(10):4131–4140. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(4):213–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, Kasper JD. A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(3):372–379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ornstein KA, Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E, Wolff JL. A national profile of end-of-life caregiving in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1184–1192. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie CS, Kvale E, Fisch MJ. Multimorbidity: An issue of growing importance for oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(6):371–374. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams GR, Mackenzie A, Magnuson A, et al. Comorbidity in older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2016;7(4):249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riffin C, Van Ness PH, Wolff JL, Fried T. Multifactorial examination of caregiver burden in a national sample of family and unpaid caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(2):277–283. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srirangam SJ, Pearson E, Grose C, Brown SC, Collins GN, O’Reilly PH. Partner’s influence on patient preference for treatment in early prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2003;92(4):365–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: A qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(7):1146–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shepherd HL, Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Physician-identified factors affecting patient participation in reaching treatment decisions. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1724–1731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Charles C, et al. The TRIO Framework: Conceptual insights into family caregiver involvement and influence throughout cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(11):2035–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray TF, Nolan MT, Clayman ML, Wenzel JA. The decision partner in healthcare decision-making: A concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;92:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim Y, Carver CS, Shaffer KM, Gansler T, Cannady RS. Cancer caregiving predicts physical impairments: Roles of earlier caregiving stress and being a spousal caregiver. Cancer. 2015;121(2):302–310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: Across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2556–2568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shields GS, Sazma MA, McCullough AM, Yonelinas AP. The effects of acute stress on episodic memory: A meta-analysis and integrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017;143(6):636–675. doi: 10.1037/bul0000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staal MA. Stress, Cognition, and Human Performance: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. Moflett Field, California: NASA; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker KS, Gibson S, Georgiou-Karistianis N, Roth RM, Giummarra MJ. Everyday executive functioning in chronic pain: Specific deficits in working memory and emotion control, predicted by mood, medications, and pain interference. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(8):673–680. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krause AJ, Simon EB, Mander BA, et al. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18(7):404–418. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(7):563–579. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allen AP, Curran EA, Duggan Á, et al. A systematic review of the psychobiological burden of informal caregiving for patients with dementia: Focus on cognitive and biological markers of chronic stress. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;73:123–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vitaliano PP, Ustundag O, Borson S. Objective and subjective cognitive problems among caregivers and matched non-caregivers. Gerontologist. 2017;57(4):637–647. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schulz R, Tompkins CA. Informal caregivers in the United States: Prevalence, caregiver characteristics, and ability to provide care. In National Research Council The Role of Human Factors in Home Health Care: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010:117–144 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beach SR, Schulz R. Family caregiver factors associated with unmet needs for care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(3):560–566. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fulmer T, Paveza G, VandeWeerd C, et al. Dyadic vulnerability and risk profiling for elder neglect. Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):525–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beach SR, Schulz R, Williamson GM, Miller LS, Weiner MF, Lance CE. Risk factors for potentially harmful informal caregiver behavior. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melnyk BM, Orsolini L, Tan A, et al. A national study links nurses’ physical and mental health to medical errors and perceived worksite wellness. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(2):126–131. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7642):488–491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(11):1571–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hammer MJ, Ercolano EA, Wright F, Dickson VV, Chyun D, Melkus GD. Self-management for adult patients with cancer: An integrative review. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(2):E10–E26. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kassianos AP, Raats MM, Gage H, Peacock M. Quality of life and dietary changes among cancer patients: A systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(3):705–719. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiggins JM, Opoku-Acheampong AB, Baumfalk DR, Siemann DW, Behnke BJ. Exercise and the tumor microenvironment: Potential therapeutic implications. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2018;46(1):56–64. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vernieri C, Casola S, Foiani M, Pietrantonio F, de Braud F, Longo V. Targeting cancer metabolism: Dietary and pharmacologic interventions. Cancer Discov. 2016;6(12):1315–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(1):123–133. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Waart H, Stuiver MM, van Harten WH, et al. Effect of low-intensity physical activity and moderate- to high-intensity physical exercise during adjuvant chemotherapy on physical fitness, fatigue, and chemotherapy completion rates: Results of the PACES randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1918–1927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cené CW, Haymore LB, Lin FC, et al. Family member accompaniment to routine medical visits is associated with better self-care in heart failure patients. Chronic Illn. 2015;11(1):21–32. doi: 10.1177/1742395314532142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stamp KD, Dunbar SB, Clark PC, et al. Family partner intervention influences self-care confidence and treatment self-regulation in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;15(5):317–327. doi: 10.1177/1474515115572047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jassem J, Ozmen V, Bacanu F, et al. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer: A multinational analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(5):761–767. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jackson SE, Steptoe A, Wardle J. The influence of partner’s behavior on health behavior change: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):385–392. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Litzelman K, Blanch-Hartigan D, Lin CC, Han X. Correlates of the positive psychological byproducts of cancer: Role of family caregivers and informational support. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(6):693–703. doi: 10.1017/S1478951517000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aoun S, Deas K, Toye C, Ewing G, Grande G, Stajduhar K. Supporting family caregivers to identify their own needs in end-of-life care: Qualitative findings from a stepped wedge cluster trial. Palliat Med. 2015;29(6):508–517. doi: 10.1177/0269216314566061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brémault-Phillips S, Parmar J, Johnson M, et al. The voices of family caregivers of seniors with chronic conditions: A window into their experience using a qualitative design. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):620. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2244-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E, et al. The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: A systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2012;2(3):224–230. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Needleman J, Hassmiller S. The role of nurses in improving hospital quality and efficiency: Real-world results. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(4):w625–w633. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.w625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization; Mission and Functions of the Nurse Nursing in Action Project: Health for All Nursing Series, No. 2 Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Honea NJ, Brintnall R, Given B, et al. Putting Evidence Into Practice®: Nursing assessment and interventions to reduce family caregiver strain and burden. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):507–516. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.507-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016;122(13):1987–1995. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Families Caring for an Aging America. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, Breitbart W. Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and overview. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(6):1631–1641. doi: 10.1017/S1478951515000450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grande GE, Austin L, Ewing G, O’Leary N, Roberts C. Assessing the impact of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) intervention in palliative home care: A stepped wedge cluster trial. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(3):326–334. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]