Abstract

We used primary cultures of cortical neurons to examine the relationship between β-amyloid toxicity and hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein, the biochemical substrate for neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's brain. Exposure of the cultures to β-amyloid peptide (βAP) induced the expression of the secreted glycoprotein Dickkopf-1 (DKK1). DKK1 negatively modulates the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, thus activating the tau-phosphorylating enzyme glycogen synthase kinase-3β. DKK1 was induced at late times after βAP exposure, and its expression was dependent on the tumor suppressing protein p53. The antisense induced knock-down of DKK1 attenuated neuronal apoptosis but nearly abolished the increase in tau phosphorylation in βAP-treated neurons. DKK1 was also expressed by degenerating neurons in the brain from Alzheimer's patients, where it colocalized with neurofibrillary tangles and distrophic neurites. We conclude that induction of DKK1 contributes to the pathological cascade triggered by β-amyloid and is critically involved in the process of tau phosphorylation.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, β-amyloid, Wnt pathway, Dickkopf-1, tau phosphorylation, apoptosis

Introduction

Evidence from human genetics and transgenic mice suggests that an overproduction of β-amyloid peptide (βAP) is a primary event in the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). βAP applied to neuronal cultures induces apoptosis (Loo et al., 1993), a phenotype of death that is also observed in the AD brain (Cotman and Anderson, 1995; Smale et al., 1995). How this can be reconciled with the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) is uncertain because, at least in vitro, neurons exposed to βAP die too rapidly to allow the formation of NFTs. NFTs might arise in neurons that in vivo escape a fast execution of apoptotic death (Caricasole et al., 2003).

DNA damage associated with p53 expression may be a point of convergence of multiple intracellular pathways related to βAP toxicity (Zhang et al., 2002). p53 induces a number of genes that promote either DNA repair or apoptotic death (Lakin and Jackson, 1999; Shen and White, 2001). We wondered whether a p53 transcription program is involved in the formation of NFTs in βAP-treated neurons. Formation of NFTs results from a hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein, which is potentially driven by glycogen-synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) (Takashima et al., 1998; Otth et al., 2002), an enzyme that is under the control of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (Grimes and Jope, 2001). This pathway is activated by different Wnt secreted glycoproteins that interact with the Frizzled and LRP5/6 (LDL receptor-related protein type 5 and 6) membrane coreceptors (Dale, 1998). Activation of the Wnt pathway leads to inhibition of GSK3β by dissociating the enzyme from a multiprotein complex that involves axin, adenomatous polyposis coli, and β-catenin (Willert and Nusse, 1998) and via phosphorylation of GSK3β on Ser9 (Fukumoto et al., 2001). This results in the stabilization of the underphosphorylated form of β-catenin, which is no longer targeted for degradation by the proteasome and is then made available for its transcriptional and cell adhesion functions (Hinck et al., 1994; Willert and Nusse, 1998). Recent evidence suggests that a loss of Wnt function is implicated in the pathophysiology of neuronal degeneration in AD (De Ferrari and Inestrosa, 2000; Garrido et al., 2002; Inestrosa et al., 2002; De Ferrari et al., 2003). The canonical Wnt pathway is negatively modulated by the extracellular protein Dickkopf-1 (DKK1), which binds to LRPs preventing their interaction with Wnts (Zorn, 2001). DKK1 is induced by p53 (Wang et al., 2000) and might therefore be a component of the sequence of events leading to neuronal toxicity in response to βAP. Induction of DKK1 would prevent the inhibition of GSK3β by Wnt, thus facilitating phosphorylation of tau protein and formation of NFTs in neurons that survive a rapid execution of apoptotic death. We now report that DKK1 is expressed in cultured cortical neurons exposed to βAP as well as in neurons from autoptic brain samples of AD patients. In addition, we show that βAP-induced DKK1 expression is under the control of p53 and is causally related to hyperphosphorylation of tau in neurons challenged with βAP.

Materials and Methods

Culture preparation, treatments, and assessment of neuronal death. All experiments were performed in compliance with the European Union use of laboratory animals, the guidelines of the Italian Decreto Legislativo 27/1/92, number 116, article 7, and according to the institutional approved protocol number 9213. Cultures of pure cortical neurons were obtained from embryonic day (E) 15 rat embryos according to a well established method that allows the growth of a >99% pure neuronal population (Copani et al., 1999). βAP(25-35) was purchased from Bachem Feinchemikalien AG (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Different lots of the peptide were used. βAP (25-35) was solubilized in sterile, doubly distilled water at an initial concentration of 2.5 mm and stored frozen at -20°C. It was used to a final concentration of 25 μm in the presence of the glutamate receptor antagonists MK-801 [(+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo [a,d] cyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate] (10 μm) and DNQX (30 μm) to avoid the potentiation of endogenous glutamate toxicity (Copani et al., 1999). In some experiments, cultures were treated with the following “end-capped” phosphorothioate antisense (As) oligonucleotides: p53-As, 5′- gacctcaggtggctcatacgg-3′; p53-Sense (Sn), 5′-ccgtatgagccacctgaggtc-3′ (Chen et al., 1999); DKK-As, 5′-cgtcggagggag gcgagc-3′; DKK-Sn, 5′-gctcgcctccctccgacg-3′. Oligonucleotides (3 μm; MWG-Biotech, Firenze, Italy) were applied to cultures 16 hr before the addition of βAP. Assessment of neuronal death was performed by combining MTT assay and cytofluorimetric analysis of hypoploid DNA (Copani et al., 1999; Copani et al., 2002).

Reverse transcriptase-PCR and real-time PCR analysis. Total RNA was extracted from the cultures as described previously (Godemann et al., 1999). Total RNA was subjected to DnaseI treatment (Roche, Hertforshire, UK) and 2 μg of total RNA/sample were used for cDNA synthesis using Superscript II (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) and an oligodT primer. Each reverse transcriptase (RT) product was diluted to 100 μl with sterile, distilled water, and 1 μl of cDNA was used in the subsequent PCR amplification. β-actin cDNA amplification was performed by using a pair of primers (Roelen et al., 1994), which span an intron and yield products of different sizes depending on whether cDNA or genomic DNA is used as a template (400 bp for a cDNA-derived product, and 600 bp for a genomic DNA-derived amplification). The following pairs of primers were used:

FZD1-FOR AAGTATGGCTGAGGAGGCGGT

FZD1-REV GGTCTGATTGTACGCGATGTC

FZD2-FOR CCATCATCTTCCTGTCCGGTT

FZD2-REV GGAAGTACTGCGAATTGGCCT

FZD3-FOR TATGGCTGGCAGTGTATGGTG

FZD3-REV TAATGCCGGCTAAGAGGAGAG

FZD4-FOR TAGTGGATGCCGATGAGCTGA

FZD4-REV TCCACATGCCTGAAGTGATGC

FZD5-FOR GTGCACAGTCGTCTTCCTCTT

FZD5-REV GCCTCGTAGCGAGTTCAGGTT

FZD6-FOR TTAGTGACGCTTCTTGGCTGC

FZD6-REV GCCATGCTTCTTCTTGTGCCT

FZD7-FOR TTACTTCTTCGGCATGGCCAG

FZD7-REV TCTTGGTGCCATCGTGCTTCA

FZD8-FOR CACAGCTGAGGAATGCCGAAT

FZD8-REV GGCTGCGATGAACATAGTGGA

FZD9-FOR GTGTTCACCTTCCTGCTGGAG

FZD9-REV AGCCAGGAACCAGGTGAGAGT

FZD10-FOR TTCTTCTCCAGCGCCTTCACC

FZD10-REV AGCTGGCCATGCCGAAGTAGT

Wnt1-FOR TCCTCCACGAACCTGCTGACA

Wnt1-REV GTCGCAGGTGCAGGATTCGAT

Wnt2-FOR TGGTGGTACATGAGAGCGACA

Wnt2-REV AATACAACGCCAGCTGAGGAG

Wnt2B-FOR ACCTGAGGAGGCGATATGATG

Wnt2B-REV ACAGCACAGCACCAGTGGAAT

Wnt3-FOR CTGGTGTAGCCTTGCCAGTCA

Wnt3-REV CTTCACCTCACAGCTGCCAGA

Wnt3A-FOR CATCGCCAGTCACATGCACCT

Wnt3A-REV CGTCTATGCCATGCGAGCTCA

Wnt4-FOR GAAGGCCATCCTGACACACAT

Wnt4-REV ACACCAGGTCCTCATCCGTAT

Wnt5A-FOR AAGCAGGTCGCAGGACAGTAT

Wnt5A-REV TCTGAGGTCTTGTTGCACAGG

Wnt5B-FOR GGAACTGACCAACAGCCGCTT

Wnt5B-REV GGTCCACGATCTCGGTGCATT

Wnt6-FOR GCTGCGGAGATGATGTCGACT

Wnt6-REV GAATCGGCTGCGTAGAGGAGA

Wnt7B-FOR CAAGGAGAAGTACAACGCAGC

Wnt7B-REV CACTTGACGAAGCAACACCAG

Wnt8A-FOR CGCAGAGGCTGAGCTGATCTT

Wnt8A-REV CACACTTGACCGTGCAACACC

Wnt9A-FOR AGCACTACCAATGAAGCCACC

Wnt9A-REV ACACTGCCTGCACTCCACATA

Wnt10A-FOR TCACTCCGACCTGGTCTACTT

Wnt10A-REV CTCAGTGATGCGGCATTCTTC

Wnt10B-FOR AGAGTGCGTTCTCCTTCTCCA

Wnt10B-REV CATGTCGTGATTACAGCCACC

Wnt11-FOR AAGTGGTACACCGGCCTATGG

Wnt11-REV TCACTTGCAGACGTAGCGCTC

Wnt16-FOR CAGTACGGCATGTGGTTCACG

Wnt16-REV CTCTCCTGCGCATCTTCCTCT

LRP5-FOR GGCCAGTGGTCCCTTTCC

LRP5-REV GGCTATGAAGTTGAGAGGCAC

LRP6-FOR AGCGGCAGTGCATTGA

LRP6-REV ATCCGATTTATCCTGGCAGTT

DKK1-FOR AATCTGCCTGGCTTGCCGAA

DKK1-REV GTGGAGCCTGGAAGAATTGC

Real-time PCR was performed using an I-Cycler and the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Primer sequences were designed to different exons of the rat DKK1 and β-actin genes. Primer sequences were as follows: DKK1-FOR 5′- GCTGCATGAGGCACGCTAT-3′; DKK1-REV 5′- AGGGCATGCATATTCCGTTT-3′; β-actin-FOR 5′- CCCTGGCTCCTAGCACCAT-3′; β-actin-REV 5′-GAGCCACCAATCCACACAGA-3′. Reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C/5′; 35 × (95°C/30′; 55°C/30′). Results were analyzed with the I-Cycler Optical System software version 3.0a and represented as means ± SEM.

T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor-based luciferase reporter studies. Transfections and reporter assays were performed essentially as described previously (Caricasole et al., 2002). Transient transfections of primary cortical neurons were performed in triplicate using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Neurons (∼3 × 105 per well in 24-well plates) were transfected at 12 d in vitro. A total of 1.02 μg of DNA was transfected into each well, including luciferase reporter plasmid (200 ng), expression construct (250-800 ng of each expression construct, for up to two different plasmids), Renilla luciferase cytomegalovirus-driven internal reporter (20 ng; Promega, Madison, WI), and carrier plasmid DNA (pBluescript; Promega; to 1.02 μg) as appropriate. The luciferase reporter plasmid was the p4TCF, comprising four copies of a T-cell factor (TCF) responsive element upstream of a TATA element-luciferase coding sequence transcriptional unit (Bettini et al., 2002). After replacement of transfection medium with culture medium, βAP was added to a final concentration of 25 μm to wells, as appropriate. Luciferase activity was measured using the Promega Dual Luciferase Assay Reagent and read using a Berthold (Bad Wildbad, Germany) LUMAT LB3907 tube luminometer. Readings were from triplicate transfections and were automatically normalized relative to the internal standard (Renilla luciferase).

Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis was performed on total cell extracts (Copani et al., 2002). The primary antibodies (Abs) were: anti-goat DKK1 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-mouse paired helical filament (PHF)-1 (1:100; kindly provided by Dr. Peter Davies, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Yeshiva University, Bronx, NY), anti-mouse p53 (5 μg/ml; Oncogene Sciences, Uniondale, NY), anti-rabbit Bax (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-rabbit GSK3β, phospho (ser9) (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA).

Immunohistochemistry. Human brain specimens were obtained at autopsy from the Department of Pathology of the Academic Medical Center (University of Amsterdam), the Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, and the Netherlands Brain Bank (R. Ravid, coordinator). Permission was obtained for performing autopsies, for the use of tissue, and for access to medical records for research purposes. Clinical diagnosis was neuropathologically confirmed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue from different sites. For this study, we used material from six AD patients and six age-related nondemented controls (see Fig. 6 legend). The average postmortem interval was 8.3 ± 0.9 hr for normal controls and 4.2 ± 0.7 hr for AD cases. Staging of AD was evaluated according to Braak and Braak (1995), and adjacent sections were immunostained for Aβ, tau protein, and Congo red as described previously (Arends et al., 2000). Formalin-fixed (4%; 24 hr) paraffin-embedded tissue from the temporal and frontal cortex was used. Sections (5 μm thick) were mounted on poly-l-lysine-coated tissue slides and deparaffinized. Subsequently, sections were immersed in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min to quench endogenous peroxide activity, treated in 10 mm, pH 6.0, citrate buffer, and heated by microwave for 10 min for antigen retrieval. The slides were allowed to cool for 20 min in the same solution at room temperature and then washed in PBS. Normal serum and antibodies were dissolved in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin. Sections were preincubated for 30 min with normal rabbit or goat serum (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Anti-DKK1 Abs obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (goat polyclonal; raised against an internal region of human DKK1; 1:100) and from Ab-Cam (goat polyclonal; raised against the C terminus of DKK1; 1:100), anti-p53 Ab (clone DO-7/BP53-12; 1:2000; NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA), and anti-tau (clone AT8; against hyperphosphorylated tau; 1: 2000; Innogenetics, Gent, Belgium) were incubated 30 min at room temperature and at 4°C overnight. Sections were then washed thoroughly with PBS and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr with the appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody diluted in PBS (rabbit anti-goat Ig, 1:300, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; 1:200, goat-anti mouse Ig, 1: 200, Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Single-label immunocytochemistry was performed using an avidin-biotin peroxidase method (Vector Elite) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin or Congo red and mounted with Depex (BDH Chemicals, Poole, UK). Sections incubated without the primary antibody or with preimmune sera were essentially blank.

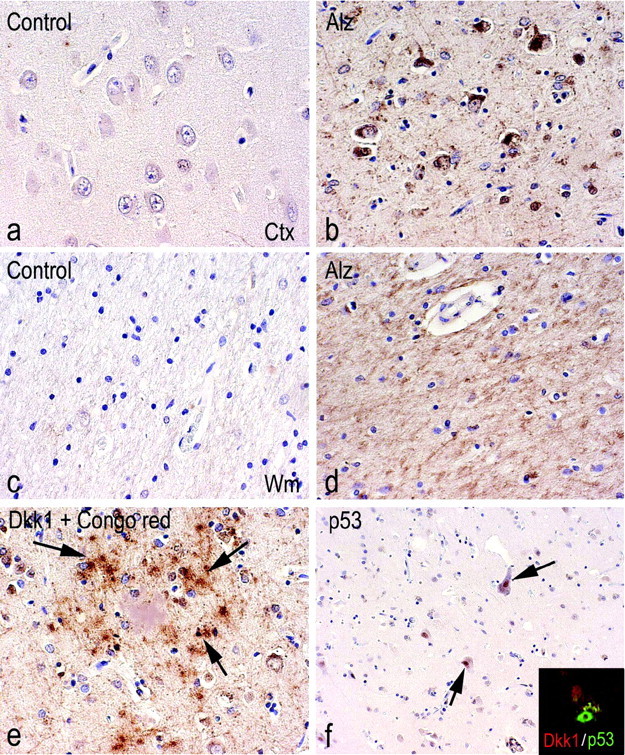

Figure 6.

a-f, Temporal cortex and white matter immunostained for DKK1 from a representative AD case (b, d, e, f) and an age-matched control (a, c). The examined cases include six nondemented controls (age at death, 77 ± 4.36), three senile dementia of Alzheimer type (SDAT) (age at death, 85.6 ± 4.8), one familial SDAT (age at death, 76), one AD (age at death, 70), and one presenil AD (age at death, 68). DKK1 immunostaining is found in temporal cortex (Ctx) (b) and white matter (Wm) (d) in AD cases. No staining is observed in nondemented controls (a, c). In e, DKK1-positive glial cells (pointed by arrows) surrounding a Congo red-positive plaque are shown. In f, p53-positive cells from temporal cortex of AD are illustrated. A confocal image of DKK1 expression (red) in neurons bearing p53 nuclear expression (green) is shown in the inset. Alz, Alzheimer's dementia.

For double labeling, sections (after incubation with primary Abs; DKK1 and P53 or AT8) were incubated for 1 d at 4°C with Alexa Fluor 568 anti-goat IgG and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). To block auto fluorescence caused by the presence of lipofuscin pigment in the tissue, sections were stained with Sudan Black B (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 10 min. Sections were then analyzed by means of a laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad; MRC1024) equipped with an argon-ion laser.

To analyze the percentage of DKK1-positive structures, sections labeled with DKK1 and PHF-tau (AT8) were digitized using an Olympus Vanox microscope equipped with a DP-10 digital camera (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). Images (200× magnification) from representative fields of the lesion in two double-labeled sections of four AD cases were collected with an Apple Macintosh Power PC 82 computer. The total number of neurons stained with PHF-tau, as well as the structures double-labeled for DKK1 and PHF-tau, was counted. We calculated the percentages of structures immunoreactive for PHF-tau that also contained DKK1 immunoreactivity.

Results

Apoptotic death and tau hyperphosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons exposed to βAP

We used pure cultures of rat cortical neurons devoid of astrocytes and other contaminating cells. These cultures respond to βAP (fragments 1-42, 1-40, or 25-35) with the activation of an unscheduled cell cycle, which leads to an increased p53 expression and apoptotic cell death within 24 hr (Copani et al., 1999, 2002). Treatment with 25 μm βAP enhanced the expression of the proapoptotic protein Bax at times that coincide with the increased expression of p53. The antisense-induced knock-down of p53 prevented the induction of Bax and attenuated neuronal death in βAP-treated cultures (Fig. 1). Immunoblots with the PHF-1 antibody (which detects the phosphorylated tau epitopes Ser 396 and 404) showed that a 20 hr exposure to βAP induced an increase in tau protein phosphorylation (Fig. 2). To avoid the fast p53-dependent apoptosis of neurons and allow a full development of tau phosphorylation, βAP-treated cultures were exposed to a caspase-3 inhibitor. The caspase-3 inhibitor Z-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-CHO (z-DEVD), which prevented βAP-induced apoptosis (percentage of neuronal survival: control, 100 ± 4.3; 24 hr βAP, 42 ± 3.3; 24 hr βAP plus z-DEVD, 20 μm, 78 ± 5.2*; 24 hr z-DEVD, 97 ± 2.5; n = 3; *p < 0.05 vs βAP alone), mediated amplification of tau phosphorylation (Fig. 2). Tau phosphorylation was prevented by lithium ions added to the cultures 7 hr after βAP (Fig. 2). Although lithium has multiple mechanisms of action, this effect might be attributable to the inhibition of GSK3β, an enzyme that phosphorylates tau on the Ser residues recognized by PHF-1 (Godemann et al., 1999). Accordingly, the selective inhibitor of GSK3β, 4-Benzyl-2-methyl-1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione (TDZD-8) (50 μm), reproduced the effects of lithium ions when applied to the cultures 7 hr after βAP.

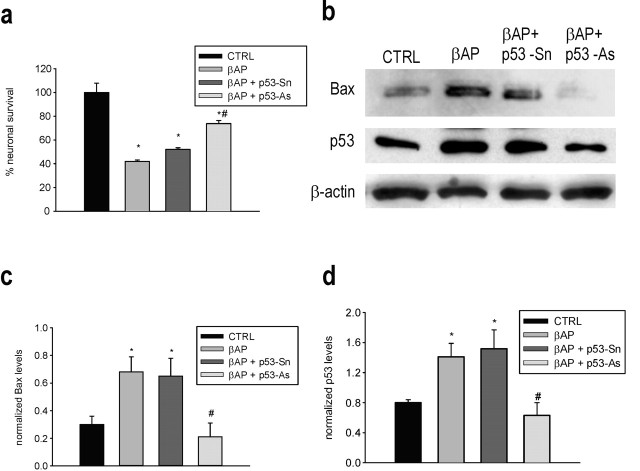

Figure 1.

Protective effects of p53 knock-down in pure neuronal cultures exposed to βAP. a, p53 antisense oligonucleotides (p53-As) increase neuronal survival in cultures exposed to 25 μm βAP(25-35) for 24 hr. Values are means ± SEM of four determinations. *p < 0.05 versus controls (CTRL); #p < 0.05 versus βAP alone (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test). b, Representative immunoblots of Bax (top) and p53 (bottom) in protein extracts from cortical neurons that have been treated with 25 μm βAP(25-35) for 24 hr in the absence or presence of p53 As or senses (Sn). c, d, Densitometer scan analysis from three determinations. Values represent the means ± SEM of Bax (c) or p53 (d) normalized against β-actin in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus controls, or #βAP and #βAP plus p53-Sn (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test).

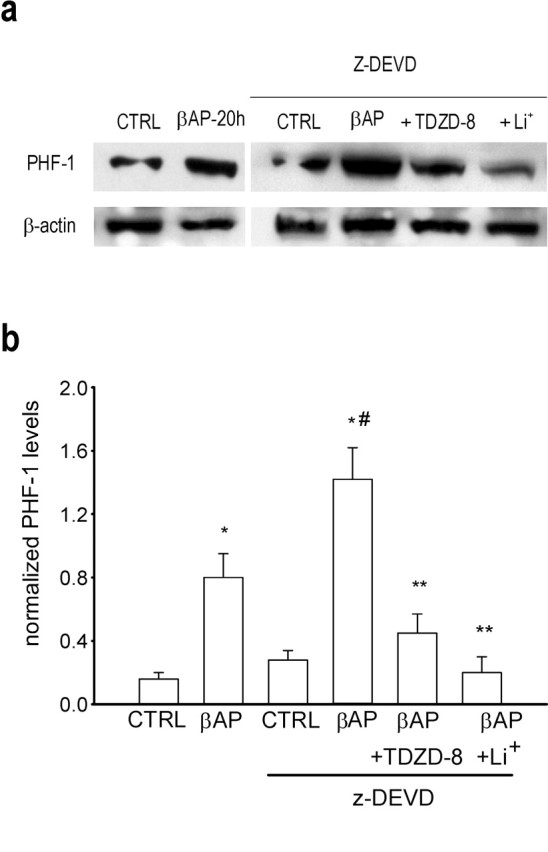

Figure 2.

GSK3β inhibitors prevent tau hyperphosphorylation in neurons treated with βAP and z-DEVD. a, Immunoblot of PHF-1 obtained from neuronal cultures treated for 20 hr with 25 μm βAP(25-35) alone or in the presence of 20 μm z-DEVD; 100 μm LiCl or 50 μm TDZD-8 were added 7 hr after βAP. b, Densitometer scan analysis from three determinations. Values represent the means ± SEM of PHF-1 normalized against β-actin in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 versus controls (CTRL), #βAP alone, or **βAP plusz-DEVD (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test).

DKK1 is expressed and required for tau phosphorylation in βAP-treated neurons

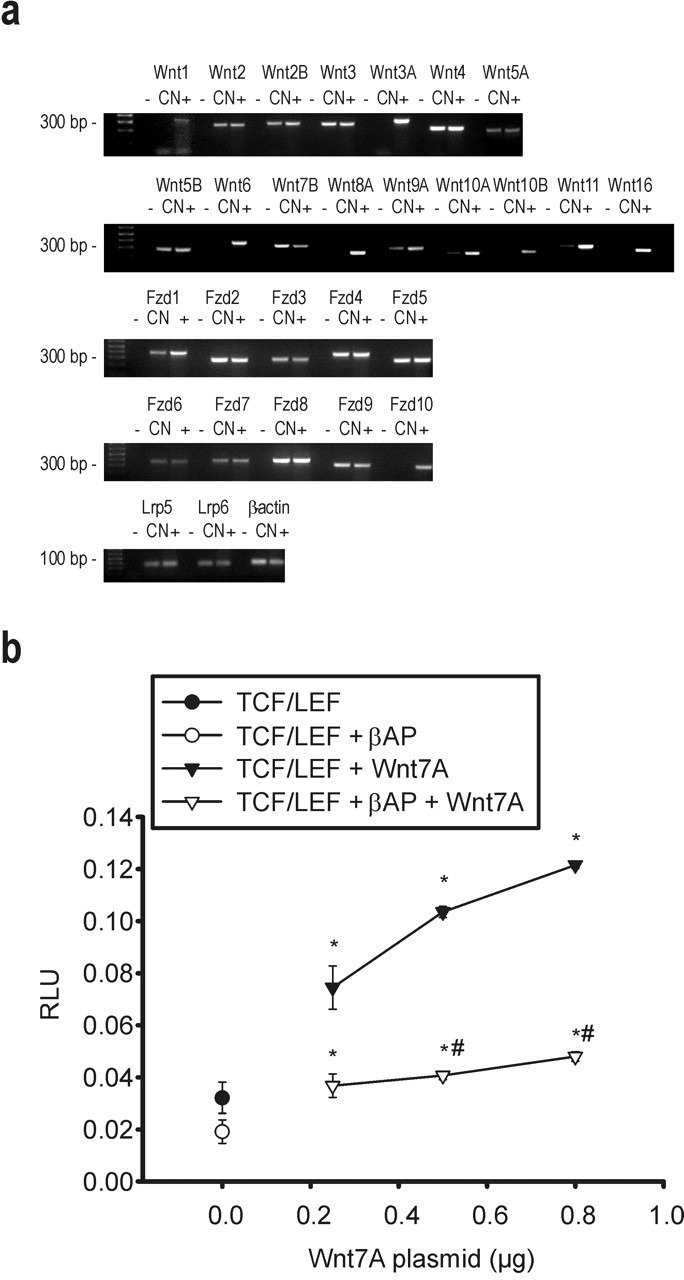

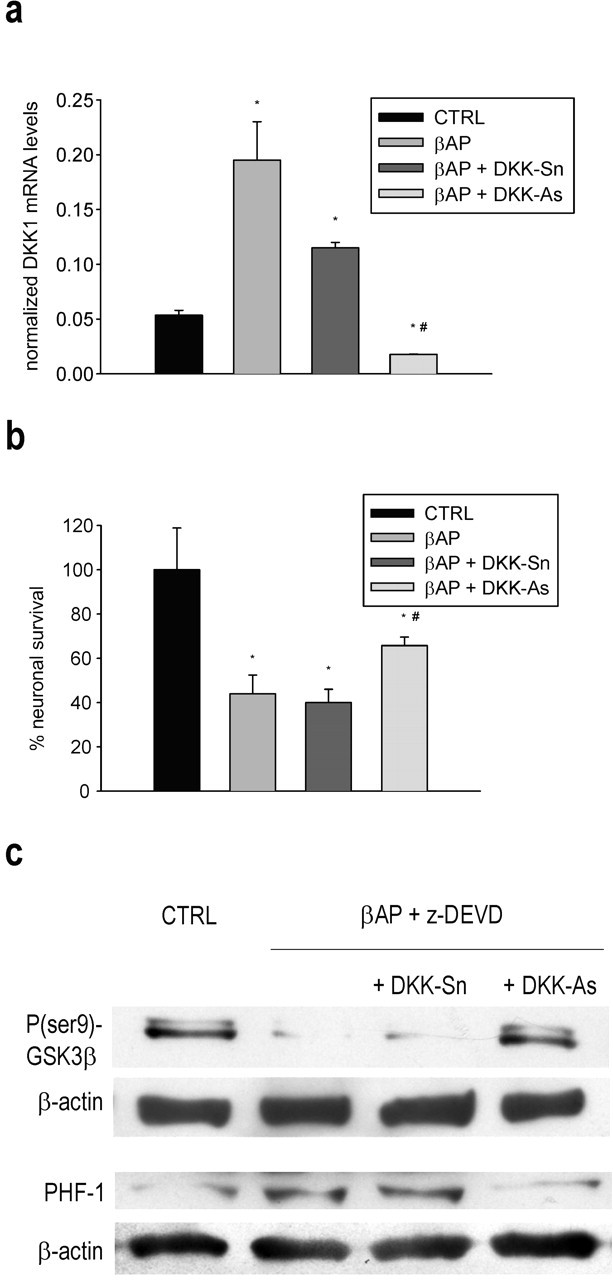

Searching for a mechanism that could link the increase in p53 expression to GSK3β activation, we examined the expression of DKK1, a protein induced by p53 that negatively modulates the Wnt pathway. Cultures constitutively expressed the DKK1/Wnt coreceptors, LRP5 and LRP6, in addition to several Wnt glycoproteins and the other Wnt coreceptor, Frizzled (Fig. 3a). In addition, we could detect a functional response to an overexpressed Wnt member (Wnt7A) in cultures that were cotransfected with a reporter gene (luciferase) under the control of a TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor responsive promoter (Fig. 3b). Thus, the Wnt transduction machinery was functional in our cultures. Interestingly, the response to Wnt7A was reduced in βAP-treated cultures (Fig. 3b), consistent with the reported inhibition of Wnt signaling by βAP (De Ferrari et al., 2003). DKK1, which might account for this reduction, was nearly absent in control cultures but became substantially expressed after 16 hr of exposure to βAP (Fig. 4a). Induction of DKK1 was prevented by p53 antisense oligonucleotides (Fig. 4b). The antisense-induced knock-down of DKK1 had only a small protective effect against neuronal apoptosis (Fig. 5b) but prevented both the activation of GSK3β, assessed through the reduction of the inactive phospho-Ser9 form of the enzyme, and the increase in tau phosphorylation that were observed after 21 hr of exposure to βAP (Fig. 5c). Treatment with DKK1 sense oligonucleotides reduced DKK1 mRNA levels induced by βAP but to a much lesser extent than the respective antisenses (Fig. 5a). However, the extent of DKK1 mRNA reduction produced by DKK1 sense oligonucleotides did not appear sufficient to protect against βAP-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5b) or to prevent both GSK3β activation and tau hyperphosphorylation (Fig. 5c).

Figure 3.

The Wnt transduction machinery is functional in cultured cortical neurons. RT-PCR analysis of mRNA for Wnt glycoproteins, Frizzled receptors, and the DKK1/Wnt coreceptors Lrp5 and Lrp6 in cortical neurons (CN) is shown in a. +, Positive control tissues (mixture of cDNA from brain, heart, liver, or kidney); -, negative controls (absence of cDNA). The 75 bp β-actin band is also shown. b, TCF/LEF-based luciferase responses to the overexpression of different concentrations of Wnt7a expression plasmid. Values are means ± SEM of three determinations normalized against the internal standard. *p < 0.05 versus the respective basal responses; #p < 0.05 versus TCF/LEF plus Wnt7A (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test). Filled and open circles indicate basal luciferase responses in the absence or presence of βAP, respectively. RLU, Relative light units.

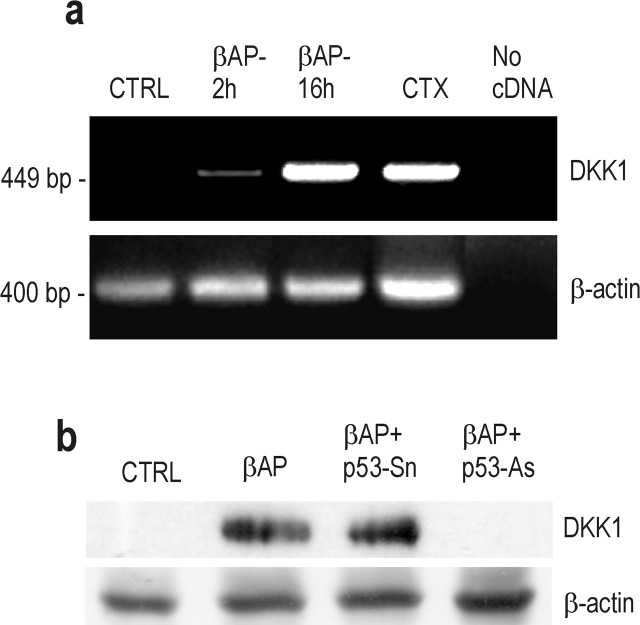

Figure 4.

p53-dependent induction of DKK1 by βAP in cultured cortical neurons. a, RT-PCR analysis of DKK1 mRNA. Cultures were treated with 25 μm βAP(25-35) for the indicated times. Expression of mRNA in rat cortex (CTX) is shown as a positive control. The 400 bp β-actin band is also shown. The 600 bp β-actin band, assessing genomic DNA contamination, was undetectable. b, Representative immunoblot of DKK1 in protein extracts from cortical neurons treated with 25 μm βAP(25-35) for 20 hr in the absence or presence of p53 As or senses (Sn). Loading controls are included.

Figure 5.

DKK1 knock-down attenuates cell death, GSK3β activation, and tau hyperphosphorylation in βAP-treated neurons. a, Real-time PCR analysis of DKK1 mRNA in neurons exposed to 25 μm βAP(25-35) for 16 hr in the presence or absence of DKK1 antisenses (DKK-As) or senses (DKK-Sn). Values are means ± SEM of normalized DKK1 from four determinations. *p < 0.05 versus controls (CTRL), or *# βAP alone (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test). The effect of DKK-As on neuronal survival (b), GSK3β activation, and tau hyperphosphorylation (c) in cultures exposed to 25 μm βAP(25-35) for 20 hr is shown. In b, values represent the means ± SEM of six determinations. *p < 0.05 versus controls (CTRL), or *# βAP alone (one-way ANOVA followed by Fisher's LSD test). In c, the immunoblot of PHF-1 was obtained from neuronal cultures treated with βAP in the presence of 20 μm z-DEVD. The β-actin band is shown for comparison. The immunoblot is representative of three independent experiments with similar results. The immunoblot of phospho(ser9)-GSK3β was obtained under the same conditions and repeated twice with similar results.

Expression of DKK1 in the AD brain

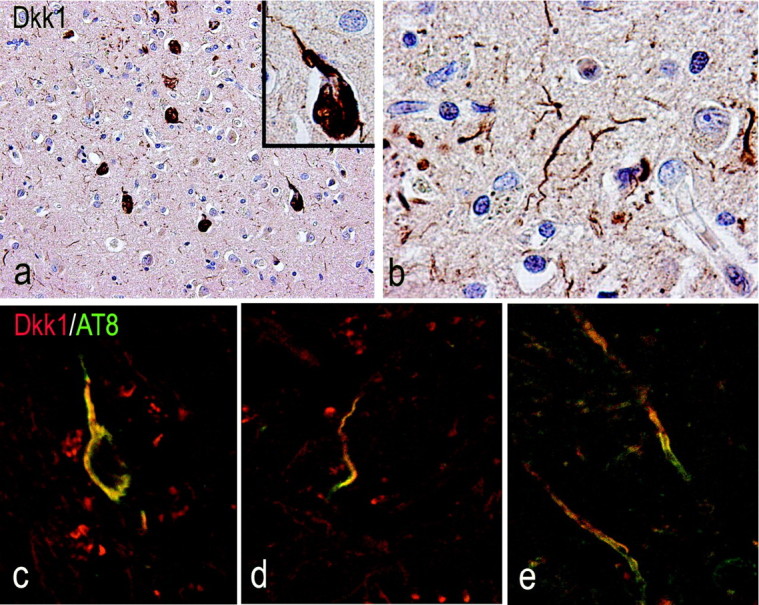

We extended the examination of DKK1 to human autopsy brain tissue from five AD patients and five age-matched controls (see Fig. 6 legend). All AD cases displayed a high degree of pathology (Braak score V-VI). Immunohistochemical processing revealed significant DKK1 immunostaining in AD temporal cortex and white matter (Fig. 6b,d). Nondemented age-matched controls showed no evidence of DKK1 expression (Fig. 6a,c). Occasional DKK1 staining was observed in glial cells surrounding Congo red-positive plaques (Fig. 6e). In AD temporal lobe sections that were double immunostained for DKK1 and p53, DKK1 was found in neurons with nuclear p53 expression (Fig. 6f, inset). Neurons with NFT morphology and dystrophic neurites also stained for DKK1 (Fig. 7a,b). In particular, AT8 phosphotau-labeled NFTs, and distrophic neurites were immunoreactive for DKK1 (Fig. 7c,d; Table 1). DKK1-positive white matter fibers also stained for AT8 (Fig. 7e; Table 1).

Figure 7.

Association of DKK1 expression and hyperphosphorylated tau in AD temporal cortex. a, b, Neurons with NFT morphology (a) and dystrophic neurites (b) stain for DKK1. c, d, The AT8 antibody reveals the location of hyperphosphorylated tau (green) in neurons (c) and dystrophic neurites (d) expressing DKK1 (red). e, AT8 stains also DKK1-positive white matter fibers.

Table 1.

DKK1 expression in AT8 phosphotau-labeled NFT and dystrophic neurites

|

|

PHF-tau |

|

|---|---|---|

| Cortex | White matter | |

| DKK1 |

85.7 ± 3.3 |

79.5 ± 5.2 |

Data represent percentages of structures immunoreactive for PHF-tau that also contained DKK1 immunoreactivity.

Data are expressed as means ± SEM from four AD patients with DKK1-positive structures.

Discussion

Recent evidence indicates that abnormalities of Wnt signaling might be involved in human brain diseases, including autism (Wassink et al., 2001), schizophrenia (Cotter et al., 1998), and AD (De Ferrari and Inestrosa, 2000; Garrido et al., 2002; Inestrosa et al., 2002; De Ferrari et al., 2003). In cultured neurons, overexpression of the Wnt antagonist, DKK1, prevents activity-dependent dendritic branching (Yu and Malenka, 2003). Our data demonstrate a role for DKK1 in the mechanisms of βAP toxicity. In tumor cell lines, DKK1 is induced by p53, which interacts with a potential responsive element located in the promoter region of the DKK1 gene (Wang et al., 2000). Consistent with the notion that DKK1 is a p53 target gene (Wang et al., 2000), induction of DKK1 was also p53 dependent in βAP-treated neurons. Thus, distinct p53-activated pathways of neuronal death occur in response to βAP, whereas the expression of Bax might account for the fast execution of apoptosis, the expression of DKK1 might subserve additional roles in the p53-activated program. DKK1 knock-down slightly reduced neuronal death induced by βAP, supporting the hypotheses that the Wnt pathway sustains neuronal survival (De Ferrari and Inestrosa, 2000; Garrido et al., 2002; Inestrosa et al., 2002; De Ferrari et al., 2003), and DKK1 behaves as a proapoptotic factor (Shou et al., 2002). In neurons that were made resistant to apoptosis by inhibition of caspase-3, we could disclose a hyperphosphorylation of tau at times that roughly coincided with the induction of DKK1 (i.e., after 16-21 hr of exposure to βAP). This particular process was inhibited by DKK1 knock-down and by lithium, which mimics the activation of the Wnt pathway by inhibiting GSK3β (De Ferrari et al., 2003). We speculate that DKK1 produced by βAP-treated neurons suppresses the canonical Wnt signaling pathway by interacting with LRP5/6 and therefore facilitates GSK3β activation. This scenario could take place in degenerating neurons of the AD brain, where DKK1 was highly expressed (whereas it was absent in control brains) and colocalized with both NFT and dystrophic neurites labeled by AT8, which recognizes phosphorylated tau in paired helical filaments. Based on recent findings on the effects of DKK1 overexpression on activity-dependent dendritic branching in neuronal cultures (Yu and Malenka, 2003), DKK1 overexpression in the AD brain would result in deficient neuronal plasticity and, together with its capacity to mediate increased tau phosphorylation (this study), likely contribute significantly to neuronal degeneration. Our demonstration that DKK1 is upregulated in the AD brain strengthens the hypothesis that an impairment of the Wnt pathway contributes to the pathophysiology of AD (De Ferrari and Inestrosa, 2000; Garrido et al., 2002; Inestrosa et al., 2002; Caricasole et al., 2003; De Ferrari et al., 2003). It is particularly interesting that the DKK1 receptor LRP5 is also one of the putative receptors for apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and that the genotype ϵ4/ϵ4 is an established risk factor for late onset AD (Saunders et al., 2000; Rocchi et al., 2003). Whether ApoE4 binds with high affinity to LRP5 and mimics the action of DKK1 on the Wnt pathway is worthy of investigation. Finally, our findings encourage the search for DKK1 antagonist molecules to be tested as selective neuroprotective agents in experimental models of AD.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer's Association. We thank Elisa Trovato Salinaro for technical assistance and Dr. Peter Davies for kindly providing the PHF-1 antibody.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Ferdinando Nicoletti, Department of Human Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Rome La Sapienza, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Rome, Italy. E-mail: ferdinandonicoletti@hotmail.com.

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/246021-07$15.00/0

A. C. and A. C. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Arends M, Duyckaerts C, Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P, Hauw J-J (2000) Microglia, amyloid and dementia in Alzheimer disease. A correlative study. Neurobiol Aging 21: 39-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettini E, Magnani E, Terstappen GC (2002) Lithium induces gene expression through lymphoid enhancer-binding factor/T-cell factor responsive element in rat PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett 317: 50-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H, Braak E (1995) Staging of Alzheimer's disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging 16: 271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricasole A, Ferraro T, Rimland JM, Terstappen GC (2002) Molecular cloning and initial characterization of the MG61/PORC gene, the human homologue of the Drosophila segment polarity gene Porcupine. Gene 288: 147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caricasole A, Copani A, Caruso A, Caraci F, Iacovelli L, Sortino MA, Terstappen GC, Nicoletti F (2003) The Wnt pathway, cell-cycle activation and beta-amyloid: novel therapeutic strategies in Alzheimer's disease? Trends Pharmacol Sci 24: 233-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R-W, Saunders PA, Wei H, Li Z, Seth P, Chuang DM (1999) Involvement of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and p53 in neuronal apoptosis: evidence that GAPDH is upregulated by p53 in neuronal apoptosis: evidence that GAPDH is upregulated by p53. J Neurosci 19: 9654-9662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copani A, Condorelli F, Caruso A, Vancheri C, Sala A, Giuffrida Stella AM, Canonico PL, Nicoletti F, Sortino MA (1999) Mitotic signaling by beta-amyloid causes neuronal death. FASEB J 13: 2225-2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copani A, Sortino MA, Caricasole A, Chiechio S, Chisari M, Battaglia G, Giuffrida-Stella AM, Vancheri C, Nicoletti F (2002) Erratic expression of DNA polymerases by beta-amyloid causes neuronal death. FASEB J 16: 2006-2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotman CW, Anderson AJ (1995) A potential role for apoptosis in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol 10: 19-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter D, Kerwin R, al-Sarraji S, Brion JP, Chadwich A, Lovestone S, Anderton B, Everall I (1998) (1998) Abnormalities of Wnt signalling in schizophrenia-evidence for neurodevelopmental abnormality. NeuroReport 9: 1379-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale TC (1998) Signal transduction by the Wnt family of ligands. Biochem J 329: 209-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari GV, Inestrosa NC (2000) Wnt signaling function in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 33: 1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ferrari GV, Chacon MA, Barria MI, Garrido JL, Godoy JA, Olivares G, Reyes AE, Alvarez A, Bronfman M, Inestrosa NC (2003) Activation of Wnt signaling rescues neurodegeneration and behavioral impairments induced by beta-amyloid fibrils. Mol Psychiatry 8: 195-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto S, Hsieh CM, Maemura K, Layne MD, Yet SF, Lee KH, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A, Taylor WG, Rubin JS, Perrella MA, Lee ME (2001) Akt participation in the Wnt signaling pathway through Dishevelled. J Biol Chem 2 76: 17479-17483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido JL, Godoy JA, Alvarez A, Bronfman M, Inestrosa NC (2002) Protein kinase C inhibits amyloid beta peptide neurotoxicity by acting on members of the Wnt pathway. FASEB J 16: 1982-1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godemann R, Biernat J, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM (1999) Phosphorylation of tau protein by recombinant GSK-3beta: pronounced phosphorylation at select Ser/Thr-Pro motifs but no phosphorylation at Ser262 in the repeat domain. FEBS Lett 454: 157-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes CA, Jope RS (2001) The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol 65: 391-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J, Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297: 353-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck L, Nelson WJ, Papkoff J (1994) Wnt-1 modulates cell-cell adhesion in mammalian cells by stabilizing beta-catenin binding to the cell adhesion protein cadherin. J Cell Biol 124: 729-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inestrosa N, De Ferrari GV, Garrido JL, Alvarez A, Olivares GH, Barria MI, Bronfman M, Chacon MA (2002) Wnt signaling involvement in beta-amyloid-dependent neurodegeneration. Neurochem Int 41: 341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakin ND, Jackson SP (1999) Regulation of p53 in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 18: 7644-7655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo DT, Copani A, Pike CJ, Whittemore ER, Walencewicz AJ, Cotman CW (1993) Apoptosis is induced by beta-amyloid in cultured central nervous system neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 7951-7955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otth C, Concha II, Arendt T, Stieler J, Schliebs R, Gonzalez-Billault C, Maccioni RB (2002) AbetaPP induces cdk5-dependent tau hyperphosphorylation in transgenic mice Tg2576. J Alzheimer's Dis 4: 417-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocchi A, Pellegrini S, Siciliano G, Murri L (2003) Causative and susceptibility genes for Alzheimer's disease: a review. Brain Res Bull 61: 1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelen BA, Lin YH, Knezevic V, Freund E, Mummery CL (1994) Expression of TGF-betas and their receptors during implantation and organogenesis of the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 166: 716-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders AM, Trowers MK, Shimkets RA, Blakemore S, Crowther DJ, Mansfield TA, Wallace DM, Strittmatter WJ, Roses AD (2000) The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer's disease: pharmacogenomic target selection. Biochim Biophys Acta 1502: 85-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, White E (2001) p53-dependent apoptosis pathways. Adv Cancer Res 82: 55-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou J, Ali-Osman F, Multani AS, Pathak S, Fedi P, Srivenugopal KS (2002) Human Dkk-1, a gene encoding a Wnt antagonist, responds to DNA damage and its overexpression sensitizes brain tumor cells to apoptosis following alkylation damage of DNA. Oncogene 21: 878-889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale G, Nichols NR, Brady DR, Finch CE, Horton Jr WE (1995) Evidence for apoptotic cell death in Alzheimer's disease. Exp Neurol 133: 225-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima A, Honda T, Yasutake K, Michel G, Murayama O, Murayama M, Ishiguro K, Yamaguchi H (1998) Activation of tau protein kinase I/glycogen synthase kinase-3beta by amyloid beta peptide (25-35) enhances phosphorylation of tau in hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Res 4: 317-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shou J, Chen X (2000) Dickkopf-1, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway, is induced by p53. Oncogene 19: 1843-1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassink TH, Piven J, Vieland VJ, Huang J, Swiderski RE, Pietila J, Braun T, Beck G, Folstein SE, Haines JL, Sheffield VC (2001) Evidence supporting WNT2 as an autism susceptibility gene. Am J Med Genet 105: 406-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willert K, Nusse R (1998) Beta-catenin: a key mediator of Wnt signaling. Curr Opin Genet Dev 8: 95-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Malenka RC (2003) Beta-catenin is critical for dendritic morphogenesis. Nat Neurosci 6: 1179-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, McLaughlin R, Goodyer C, LeBlanc A (2002) Selective cytotoxicity of intracellular amyloid beta peptide1-42 through p53 and Bax in cultured primary human neurons. J Cell Biol 156: 519-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorn AM (2001) Wnt signalling: antagonistic Dickkopfs. Curr Biol 11: R592-R595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]