Abstract

Ca2+ entry through transmitter-gated cation channels, including ATP-gated P2X channels, contributes to an array of physiological processes in excitable and non-excitable cells, but the absolute amount of Ca2+ flowing through P2X channels is unknown. Here we address the issue of precisely how much Ca2+ flows through P2X channels and report the finding that the ATP-gated P2X channel family has remarkably high Ca2+ flux compared with other channels gated by the transmitters ACh, serotonin, protons, and glutamate. Several homomeric and heteromeric P2X channels display fractional Ca2+ currents equivalent to NMDA channels, which hitherto have been thought of as the largest source of transmitter-activated Ca2+ flux. We further suggest that NMDA and P2X channels may use different mechanisms to promote Ca2+ flux across membranes. We find that mutating three critical polar amino acids decreases the Ca2+ flux of P2X2 receptors, suggesting that these residues cluster to form a novel type of Ca2+ selectivity region within the pore. Overall, our data identify P2X channels as a large source of transmitter-activated Ca2+ influx at resting membrane potentials and support the hypothesis that polar amino acids contribute to Ca2+ selection in an ATP-gated ion channel.

Keywords: ATP, P2X, synapse, calcium, permeability, channel

Introduction

Transmitter-gated cation channels (TGCCs) are key transmembrane proteins of excitable and non-excitable cells. Mammalian TGCCs can be divided into three main families on the basis of gene and protein sequences and known and predicted channel structures (Green et al., 1998). Cys-loop receptors for ACh, serotonin, GABA, and glycine form one family, and glutamate-gated channels form the second (Green et al., 1998). The third major family of mammalian TGCCs are the ATP-gated P2X channels that have a relatively simple structure compared with the other two families. To date, the quaternary structure of the channel is thought to be composed of specific combinations of three of the seven (P2X1–P2X7) known subunits (Nicke et al., 1998; Stoop et al., 1999; Jiang et al., 2003). Each subunit possesses two transmembrane segments (North, 2002), the second of which is thought to line the ion channel pore (Rassendren et al., 1997; Egan et al., 1998). P2X channels are widely expressed throughout the nervous system and underlie fast ATP neurotransmission at some neuro-neuronal synapses (Norenberg and Illes, 2000; North, 2002). For instance, P2X2 channels mediate an EPSP between myenteric neurons (Galligan and Bertrand, 1994; Khakh et al., 2000; Ren et al., 2003), and P2X1 channels underlie a fast excitatory junction potential at neuro-effector junctions (Brain et al., 2002; Lamont and Wier, 2002; Lamont et al., 2003). In addition, P2X channels are found presynaptically where they modulate neurotransmitter release (Gu and MacDermott, 1997; Khakh and Henderson, 1998; MacDermott et al., 1999; Hugel and Schlichter, 2000; Kato and Shigetomi, 2001; Nakatsuka and Gu, 2001; Khakh et al., 2003). In many instances, the physiological response is triggered by the influx of Ca2+ through P2X channels; prime examples include presynaptic responses at neuro-neuronal synapses and postsynaptic responses at neuroeffector junctions.

Most TGCCs, including P2X channels, have Ca2+ permeabilities equal to or greater than those of the 100-fold more abundant Na+ (Burnashev, 1998). When these channels open, Ca2+ moves down its electrochemical gradient and into the cell. The resulting influx of Ca2+ exerts wide-ranging physiological effects that can last for seconds, days, or weeks (Berridge et al., 2003), adding a spatial and temporal dimension to transmitter signaling that may outlast the initial millisecond time scale surge of neurotransmitter and the accompanying depolarization by factors of >109. Previous studies revealed that ATP gates a transmembrane Ca2+ flux pathway (Benham and Tsien, 1987; Rogers and Dani, 1995) that subsequently was shown to contribute to the panoply of physiological responses in cells throughout the body, including neurons, muscle, glia, immune cells, and epithelia (Khakh, 2001; Inoue, 2002; North, 2002; Schwiebert and Zsembery, 2003). However, a comprehensive examination of Ca2+ flux through the ATP-gated P2X channel family is not reported, and there is little quantitative information about how much Ca2+ flows through P2X channels in relation to other TGCCs.

In the present study, we directly measured Ca2+ flow through 11 functional recombinant P2X channels and compared these values with other TGCCs. We used patch-clamp photometry to measure fractional calcium currents (Pf%) carried by TGCCs (Schneggenburger et al., 1993). Our data suggest that, on average, P2X channels are the most Ca2+-permeable TGCCs and suggest that polar amino acids may provide the counter charges needed to partially dehydrate Ca2+ ions in a narrow part of the pore.

Materials and Methods

Molecular biology. The stable cell lines used were HEK293 cells expressing the rat 5-HT3A channel (Sarah Lummis, Medical Research Council, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK) or the human α4β2 nicotinic channel (Alison Rush, Research Labs, San Diego, CA). Wild-type and mutant rat P2X2 cDNAs were available from previous work; these mutants were generated using routine methods. Drs. Richard Evans (University of Leicester, Leicester, UK), R. Alan North (Institute of Molecular Physiology, Sheffield, UK), David Julius (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA), Thomas Küner (MPI, Hiedelberg, Germany), and Henry A. Lester (California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) supplied cDNAs encoding human P2X1, human P2X4, rat vanilloid receptor 1 (VR1), rat NR1/NR2A, and chick α4/β2 nicotinic channels, respectively. Plasmid cDNAs were transfected into HEK293 cells plated on 35 mm plastic culture dishes using Effectene (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK) and following the protocol of the manufacturer.

Patch-clamp photometry. The experimental setup is depicted in Figure 1 A. Cells expressing the protein of interest were replated at low density onto 13 mm borosilicate glass coverslips (BDH Chemicals, Poole, UK) 12–18 hr before the start of the experiment. Coverslips were transferred to a recording chamber positioned on the stage of a Nikon (Tokyo, Japan) Diaphot 200 inverted microscope equipped with a Fluor 40× objective, 100 W xenon lamp, Uniblitz (Rochester, NY) shutter, liquid light guide, and custom-made coupling. In most cases, whole-cell current was recorded at a holding potential of –55 mV using an Axopatch 1-D amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and a low resistance (1.5–5 MΩ) glass microelectrode filled with an intracellular solution of the following composition (in mm): 140 CsCl, 10 tetraethylammonium Cl, 10 HEPES, 2 fura-2 K5 (lot 3491-11; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and 4.8 CsOH, pH 7.3. Previous findings demonstrate that fura-2 reaches a steady-state intracellular concentration in HEK293 cells after 5–6 min of passive diffusion from the recording electrode (Schneggenburger et al., 1993; Burnashev et al., 1995; Schneggenburger, 1998; Frings et al., 2000). Consistent with this, we saw no increase in the steady level of resting fura-2 fluorescence 10 min after going whole cell (data not shown), and we always waited 10 min after rupturing the patch before continuing with the experiment. Agonists were applied for 0.2–4.0 sec once every 2–3 min using triple-barreled theta glass and a rapid solution changer system (Perfusion Fast-Step System SF-77; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). The extracellular bath solution contained the followinig (in mm): 140 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, and 5 NaOH to adjust the pH to 7.4.

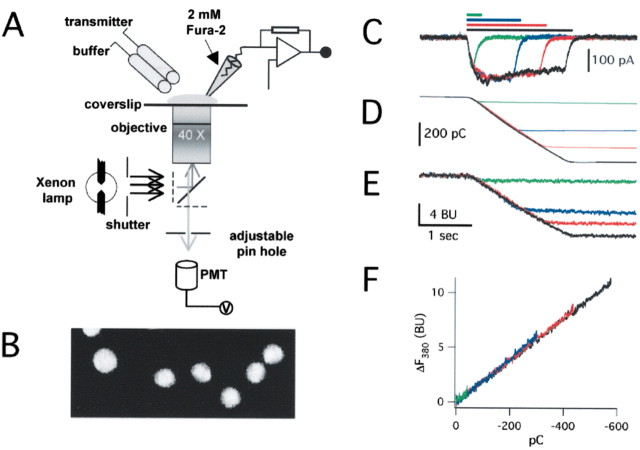

Figure 1.

Determination of fractional Ca2+ currents. A, Representation of the experimental setup used for measuring Pf%. HEK293 cells expressing molecularly defined channels were plated onto glass coverslips and patch clamped with electrodes filled with intracellular solution containing 2 mm fura-2. ATP was applied rapidly using an automated fast solution switcher. Photons were captured through a 40× objective lens. The emitted light was filtered and directed toward a photo multiplier attached to the microscope side port, and photon counts were measured in volts. The bottom photomicrograph (B) shows images of Fluoresbrite beads that were used to calibrate the voltage signal produced by the photomultiplier tube (PMT): for illustration purposes, the images shown were captured on a confocal microscope with the iris fully open. The beads have a mean diameter of 4.6 μm. C, ATP-evoked currents of increasing duration in pure Ca2+ extracellular solutions at P2X2 channels. The holding potential was –60 mV. D shows the integral of these currents, and E shows the corresponding changes in fura-2 fluorescence at 380 nm: the time course of the change in F380 matches the time course of QT for all of the traces. F, A graph of ΔF380 and QT for each of the traces shown in C–E. They all superimpose and fall on a straight line. The slope of this line represents the proportionality constant between QT and ΔF380 bead units per picocoulomb.

We determined fractional calcium current by simultaneously measuring the total membrane current and the change in emission of fura-2 excited at 380 nm (F380). Previous work shows that Pf% values can be determined accurately with a single excitation wavelength (Schneggenburger et al., 1993). An advantage of this technique is that it does not require that the absolute change in [Ca2+]i be quantified directly and thus avoids the time-consuming step needed to switch between excitation wavelengths. Rather, Ca2+ flux is measured by monitoring the change in fluorescence of fura-2 at a single wavelength, thus allowing for high time resolution measurements with a single photomultiplier tube. Whole-cell fluorescence at 510 nm was collected using a model 714 Photomultiplier Detection System (Photon Technology International, South Brunswick, NJ). The excitation filter was 380AF10 (XF1094), the dichroic was 415DCLP (XF2002), and the emitter was 510WB40 (XF3043; all from Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT). Background fluorescence was minimized by limiting the field of view of the photomultiplier tube to the immediate vicinity of the cell under investigation using an adjustable pinhole. We controlled for day-to-day variations in the efficiency of our system by normalizing the biological signal to that of the average fluorescence of five carboxy Bright Blue 4.6 μm microspheres (Polysciences, Warrington, PA) that had settled on the bottom of the bath chamber filled with the normal extracellular solution (Fig. 1 B). Thus, in keeping with previous work (Schneggenburger et al., 1993), we present changes in fura-2 fluorescence in bead units (BU) rather than volts. All data were sampled at 5 kHz using Digitdata 1200 hardware and pClamp 8.0 software by Axon Instruments; fluorescence was low-pass filtered offline at 300 Hz.

Data analysis. The Pf% was calculated as follows:

|

where QT (the integral of the ligand-gated ionic current) and QCa are given by the following:

|

Fmax is the calibration constant used to relate ΔQCa to ΔF380. It was calculated in a separate series of experiments under conditions in which QT is expected to equal QCa (Fig. 1C–E). This was achieved by the following: (1) measuring ATP-gated membrane current and fluorescence from cells expressing either P2X2 or P2X4 channels; (2) holding these cells at a membrane potential (–60 mV) at which the outward flow of ions is negligible; and (3) replacing extracellular Na+ with 112 mm Ca2+. Under these conditions, ATP elicits membrane currents carried exclusively by Ca2+, and Fmax can be determined from the slope of the plot of QT versus F380 (Fig. 1 F). Fmax, measured in this way, was 0.012 ± 0.002 BU/nC (n = 37). Data were analyzed in Clampfit 8.1 (Axon Instruments), and calculations were performed using macros written in Igor Pro (WaveMetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Results are reported as mean ± SEM for the number of cells (n) included in the study. Pf% was often measured many times in a single cell; these measures were then averaged to give the Pf% for the individual cell. Significant differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc or the Student's t test. A p value of <0.01 was considered significant.

Chemicals. All chemicals used were from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK), Molecular Probes, or Sigma.

Results

Pf% for channels gated by glutamate, serotonin, acetylcholine, and protons

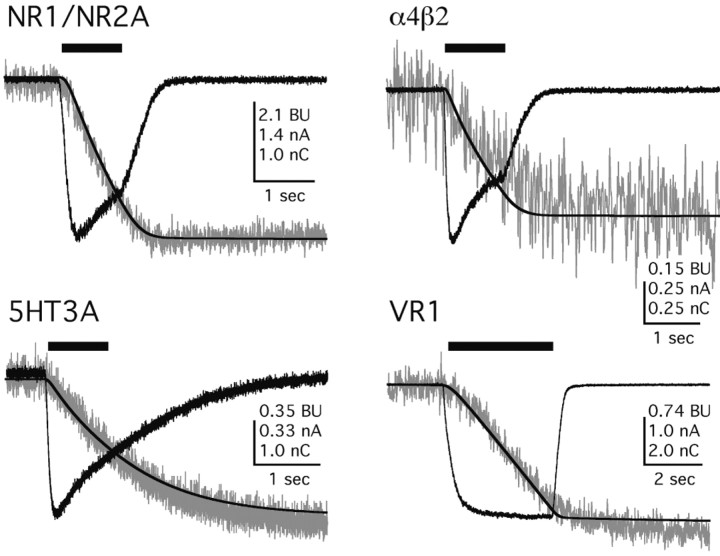

Patch-clamp photometry is the only method providing an absolute measure of Ca2+ flux for ion channels that is independent of cell type, endogenous buffer capacity, channel density, and current amplitude (Schneggenburger et al., 1993). It is also superior to reversal potential-based methods because the measurements are made in physiological solutions at resting membrane potentials and because the values for flux do not make Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz assumptions (Frings et al., 2000). Using patch-clamp photometry, we began by measuring the fractional Ca2+ current of nicotinic α4β2, serotonin 5-HT3A, proton-gated VR1, and glutamate NR1/NR2A channels (Fig. 2) because these are well characterized channels that are known to transport Ca2+ across membranes in neurons (Burnashev, 1998; MacDermott et al., 1999; Montell, 2001; Reeves and Lummis, 2002). Our Pf% values for the human α4β2, chick α4β2, and rat NR1/NR2A were 3.1 ± 0.6 (n = 5), 3.1 ± 0.8 (n = 4), and 14.1 ± 0.9% (n = 15) and are in excellent agreement with published reports (Ragozzino et al., 1998; Jatzke et al., 2002; Lax et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2002). The Pf% values of the rat 5-HT3A and rat VR1 channels are not reported previously, and we find them to be 4.7 ± 0.3% (n = 8) and 3.5 ± 0.3% (n = 30), respectively. Together, these data validate our methods and provide guideposts by which to compare the Ca2+ flux of different TGCC families.

Figure 2.

Representative traces for QT and ΔF380 at transmitter-gated channels. For all panels in this figure, the black traces are transmitter-evoked currents (in amperes) and the integral of the current QT (in nanocoulombs), whereas the gray traces are the ΔF380 (in bead units). Appropriate agonists were applied for the times indicated by the solid bars above the traces. These agonists were as follows: 100 μm glutamate in 0 mm extracellular Mg2+ with 100 μm glycine for NR1/NR2A, 100 μm (–)-nicotine for α4β2, 10 μm serotonin for 5-HT3A, and pH 5.5 for VR1.

Pf% for homomeric P2X channels gated by ATP

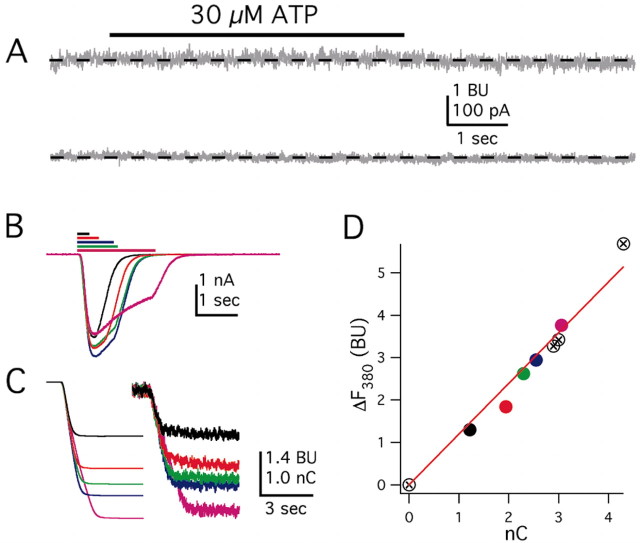

Previous detailed experiments have shown that intact HEK293 cells loaded with cell-permeable Ca2+ indicator dyes express endogenous P2Y receptors that mobilize intracellular Ca2+ in a G-protein-dependent manner (Fischer et al., 2003; He et al., 2003). We measured the effect of 30 μm ATP on untransfected and mock-transfected HEK293 cells to determine whether P2X channel-independent changes in [Ca2+]i occur under the conditions used in the experiments described in this study. In so doing, we used exactly the same experimental conditions used for the measurement of Pf% values, which is whole-cell dialysis of the cell with intracellular solution containing fura for at least 10 min. Figure 3A shows that an application of 30 μm ATP had no measurable affect on either the holding current (bottom trace) or F380 (top trace) in a mock-transfected cell. In a sample of eight cells, whole-cell fluorescence measured at 4 sec after the start of an application of 30 μm ATP was 99.9 ± 0.2% of that measured immediately before the start; this translates to a negligible decrease of 0.007 ± 0.015 BU in fura fluorescence, which implies negligible release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and no presence of endogenous P2X channels (Fig. 3A, bottom trace). We suggest that differences between our experiments showing negligible contribution of P2Y receptors and previous studies (Fischer et al., 2003; He et al., 2003) are attributable to the unavoidable experimental requirements of our approach, namely complete intracellular dialysis of the cell constituents (Schneggenburger et al., 1993). We expect that, under these conditions, metabotropic ATP receptor effects are impaired.

Figure 3.

Controls and calibrations for measurements of Pf% at P2X channels. A, Lack of effect of 30 μm ATP on membrane current (bottom trace) and F380 (top trace) in a mock-transfected HEK293 cell. B–D, Representative traces for an HEK293 cell expressing P2X2 channels and activated with 10 μm ATP for increasing durations, as indicated by the length of the bars in B. B shows the current traces (for clarity, we show only 5 of the 9 traces), and C shows the corresponding integrated currents (QT, left traces) and changes in fluorescence (ΔF380, right traces). D shows a plot of ΔF380 versus QT. The data fall on a straight line, as expected if P2X channels are the only source of Ca2+. The traces and data are colored coded in B–D so that any individual response can be compared across all graphs. In D, there are four additional data points that, for the sake of simplicity, are not illustrated in B and C.

We saw robust inward currents and decreases in F380 in transfected cells expressing P2X channels. Current and fluorescence were measured while applying 10 μm ATP for varying lengths of time (0.2–3.5 sec, as indicated by the lengths of the solid bars in Fig. 3B) to a HEK293 cell expressing homomeric P2X2 channels (Fig. 3B). Of critical importance are data showing that the time course of the decrease in F380 mirrored that of the integral of the ATP-gated current (Fig. 3C) as expected if Ca2+ enters through P2X2 channels (Schneggenburger et al., 1993). Furthermore, the plot of ΔF380 versus QT was linear (Fig. 3D). Both results suggest that the P2X channels are the sole source of the rise in [Ca2+]i. This conclusion is supported by data showing that calcium-induced calcium release is negligible in HEK293 cells studied with fura-2 (Alonzo et al., 2003). Our finding that ATP activation of endogenous P2Y receptors does not affect [Ca2+]i. under our experimental conditions probably reflects disruption of a signaling cascade mechanism caused by the obligatory 10 min dialysis of the cell interior with the contents of the recording electrode. All in all, the data provide strong evidence against a detectable contribution of endogenous metabotropic ATP receptors to the responses described in this study.

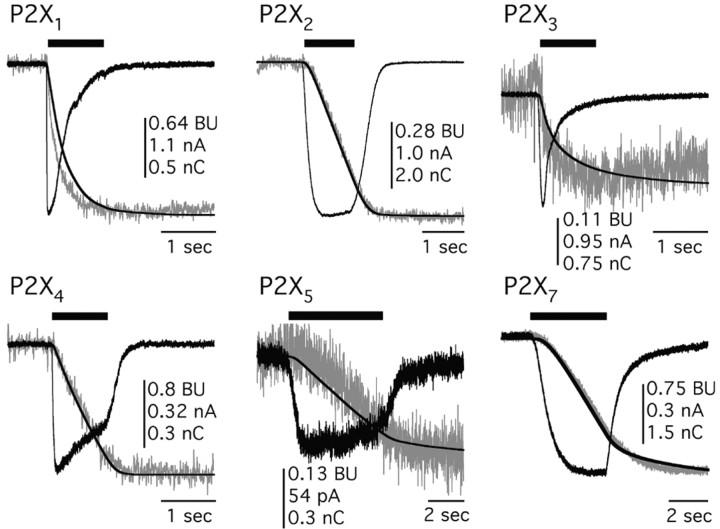

We next studied Ca2+ flux at homomeric rat P2X channels. ATP evoked inward currents and measurable decreases in fluorescence of fura-2 at 380 nm (ΔF380) in cells expressing functional homomeric P2X channels (Fig. 4). In all cases, the time course of the change in fluorescence paralleled the accumulation of charge (QT), as expected if the underlying cause of the rise in Ca2+ is the ATP-gated current. Pf% values determined for all six functional rat homomeric channels were as follows: P2X1, 12.4 ± 1.6% (n = 5); P2X2, 5.7 ± 0.3% (n = 18); P2X3, 2.7 ± 0.9% (n = 5); P2X4, 11.0 ± 0.7% (n = 14); P2X5, 4.5 ± 0.5% (n = 5); and P2X7, 4.6 ± 0.5% (n = 12). We found that Pf% was not a function of agonist concentration for P2X2 channels (5.8 ± 0.3, 5.5 ± 0.5, and 6.3 ± 0.9% for 10, 30, and 100 μm ATP, respectively, n = 13, 4, and 3, respectively; p > 0.05), although we did not study this relationship in detail for all channels. With the exception of the P2X3 channel, all ATP-gated channels show fractional Ca2+ currents that are equal to or greater than α4β2, 5-HT3A, and VR1 channels (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, both P2X1 and P2X4 channels display fractional Ca2+ currents that are equivalent (p > 0.05) to the NR1/NR2A NMDA channel that was thought previously to be an unparalleled source of transmitter-activated Ca2+ flux. The human homologues, hP2X1 and hP2X4, also gate large fractional Ca2+ currents of 10.8 ± 1.1% (n = 7) and 15.0 ± 1.5% (n = 7), respectively, demonstrating that high Ca2+ flux is conserved across species.

Figure 4.

Representative traces for QT and ΔF380 at homomeric P2X channels. For all panels in this figure, the black traces are transmitter-evoked currents (in amperes) and the integral of the current QT (in nanocoulombs), whereas the gray traces are the ΔF380 (in bead units). Appropriate agonists were applied for the times indicated by the solid bars above the traces. These agonists were as follows: 3 μm ATP for P2X1 and P2X3; 30 μm ATP for P2X2, P2X4, and P2X5; and 100 μm benzoylbenzoyl ATP for P2X7.

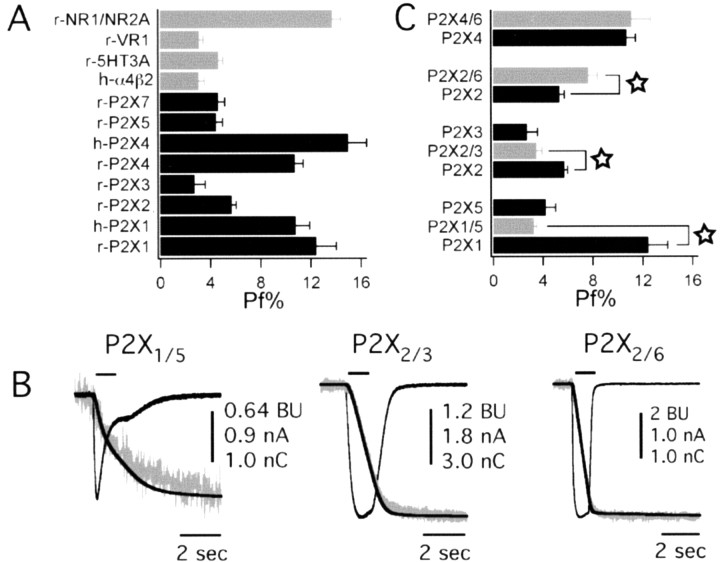

Figure 5.

Fractional Ca2+ currents for transmitter-gated channels. A, Mean data for Pf% of TGCCs compared with homomeric rat and human P2X channels. Note there is no data point for the P2X6 channel because no ATP-evoked responses could be measured. B, Representative raw data of three heteromeric rat P2X channels. These traces show ATP-evoked currents (black), QT (black), and ΔF380 (gray) for P2X1/5, P2X2/3, and P2X2/6 channels. An appropriate concentration of ATP (either 3 or 30 μm) for each channel was used to evoke current. C, Mean data for the measured Pf% values for ATP-evoked currents recorded from cells expressing combinations of P2X subunits. The stars indicate significant differences between the heteromeric assemblies and their homomeric counterparts.

Pf% for heteromeric P2X channels gated by ATP

We next cotransfected HEK293 cells with pairs of cDNAs to record the Pf% values of heteromeric rat P2X channels (Fig. 5B). Four pairs of subunits (P2X1/5, P2X2/3, P2X2/6, and P2X4/6) are known to form functional complexes (North, 2002). The current through two of these pairs, P2X1/5 and P2X2/3, can be reliably measured without significant contamination by the unpaired, homomeric channels that may also be expressed. Cotransfection of P2X1 and P2X5 produces a population of channels composed almost exclusively of heteromeric P2X1/5 channels (Torres et al., 1998). The Pf% of heteromeric P2X1/5 channels was 3.3 ± 0.2% (n = 9), a value similar to homomeric P2X5 channels (Fig. 5C). Cells cotransfected with cDNAs for P2X2 and P2X3 were studied using αβ-methylene ATP to isolate heteromeric responses (North, 2002). The Pf% of heteromeric P2X2/3 channels was 3.5 ± 0.5% (n = 9). In both cases, the heteromeric channels show the Ca2+ phenotype of the less permeable channel. Functional isolation of heteromeric P2X2/6 and P2X4/6 responses from possible homomeric channels is less straightforward because there are no agonists that separate homomeric P2X2 channels from the heteromeric pairs (North, 2002). However, we found that co-transfection of cDNAs encoding P2X2 and P2X6 subunits produced a population of ATP-gated channels that had a Pf% that was significantly greater (7.7 ± 0.7%; n = 14) than that of the P2X2 channel alone (p = 0.0074) (Fig. 5C), and these data suggest that a considerable percentage of this channel population is heteromeric (King et al., 2000). Seemingly, the P2X6 subunit imparts a sizable increase in Ca2+ flux through the pore. In contrast, cotransfection of rat P2X4 and P2X6 cDNAs resulted in an ATP-evoked current with a Pf% (11.3 ± 1.0%; n = 6) not significantly different from transfection of rat P2X4 cDNA alone, although it is possible that our measurement of Pf% at P2X4/6 channels may be dominated by homomeric P2X4 channels that are likely also expressed.

On the role of pore lining polar residues in determining Ca2+ flux at P2X2 channels

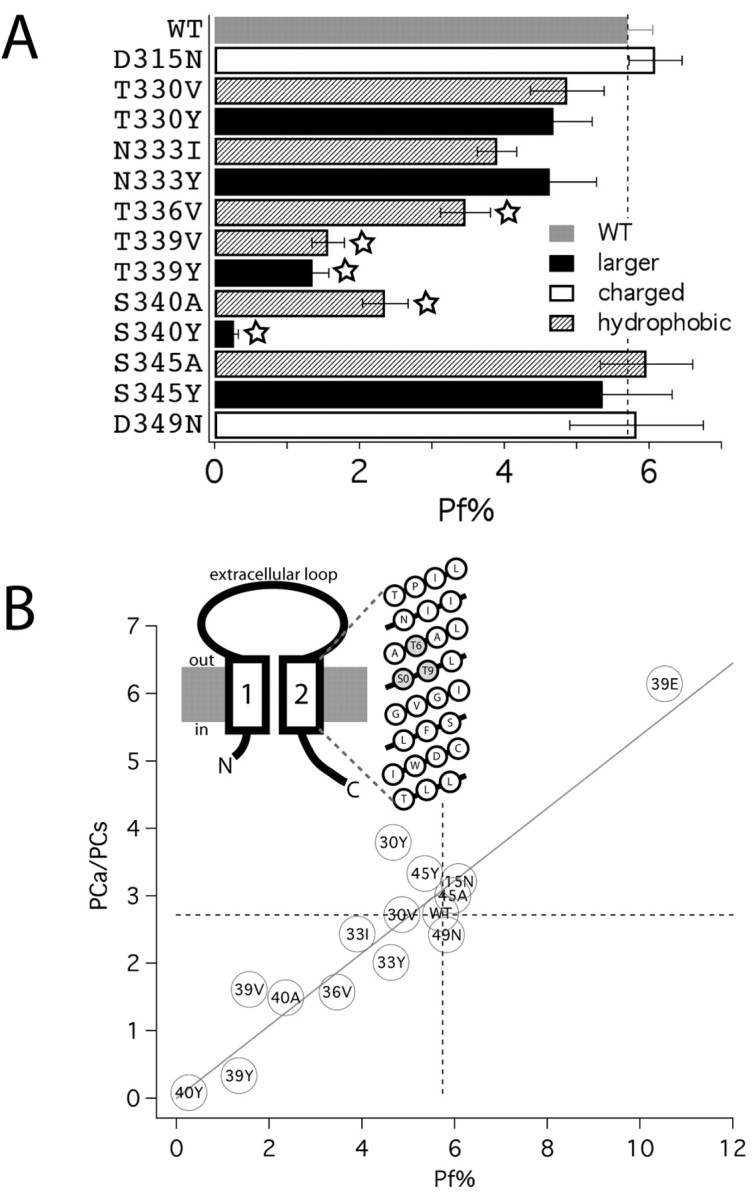

The high Ca2+ flux at nicotinic and NMDA channels occurs because of fixed charge in the pore region that may concentrate or select Ca2+ ions for permeation (Premkumar and Auerbach, 1996; Sharma and Stevens, 1996; Burnashev, 1998; Unwin, 2000; Watanabe et al., 2002). How do the structurally distinct P2X channels select for Ca2+ ions over the equally sized but ∼100-fold more abundant Na+? We focused on the involvement of the second transmembrane domain (TM2) (Fig. 6A) because it lines the channel pore (North, 2002) and ion permeation is altered in TM2 mutants (Migita et al., 2001). We focused on homomeric P2X2 channels because most of our understanding of P2X channel structure and function is derived from studies of these channels, and this wealth of data provides an appropriate framework for hypothesis-driven mutagenesis (North, 2002). P2X channels contain conserved aspartates that may occupy sites near the pore vestibules. However, we believe that these aspartates do not make an obvious contribution to Ca2+ flux because neutralizing the negative charge at D315 and D349 with asparagines had no effect on Pf% values of P2X2 channels (Fig. 6B). Next, we systematically mutated the polar amino acids that may provide a favorable environment for ion flow through the channel. Changing the character of polar residues that are primarily external (T330 and N333) or immediately internal (S345) to the putative channel gate near G342-V343-G344 (North, 2002) produced little effect on Ca2+ flux. However, increasing the hydrophobicity of three critical amino acids just extracellular to the gate (T336, T339, and S340) led to significant decreases in Pf%, suggesting that permeating ions normally interact with these polar residues in this domain. This would likely only occur in a narrow region of the pore. In keeping with this hypothesis, we found that increasing the size of these same amino acids led to either near complete absence of Ca2+ flux (T339Y and S340Y) or less informatively loss of channel function (T336Y). These data are in accord with the findings of Migita et al. (2001) (Fig. 6C), but, because our measurements report Ca2+ flow directly, they provide unequivocal evidence for a domain that regulates Ca2+ flux, just external to the gate, in the pore of P2X2 channels.

Figure 6.

Toward a molecular basis for high Ca2+ flux at P2X2 channels. A, The bar graph shows Pf% values for P2X2 mutants, as indicated with amino acids substituted for changes in side chain size, charge, and hydrophobicity. WT, Wild type. The stars indicate statistical significance. B, The diagram illustrates the presently understood membrane topology of a P2X subunit and a helical net model of the second transmembrane segment. The secondary structure of TM2 is unknown, although it is not unreasonable to assume that this segment conforms to a general pattern of helical, pore-forming domains of other ion channels (Spencer and Rees, 2002). If so, then the residues influencing Pf% at P2X2 channels cluster on one face of a predicted α helix, perhaps representing the molecular determinants of a Ca2+ selectivity filter. The graph shows the relative PCa/PCs data by Migita et al. (2001) plotted against the Pf% data shown in B. For the sake of clarity, mutants are designated by the last two digits of their position in the sequence of P2X2 and by a letter code designating the substituted amino acid. For example, T339Y is designated as 39Y. Also included are permeability and Pf% data for the mutant T339E. This mutant showed elevated Ca2+ permeability and flux, as expected after addition of fixed negative charge to a critical position within the pore (Heinemann et al., 1992).

Discussion

Because P2X channels are widely expressed in excitable and non-excitable cells throughout the body (Norenberg and Illes, 2000; North, 2002; Schwiebert and Zsembery, 2003), it is important to understand the magnitude and mechanisms of ion flow through their pores. Several laboratories have quantified Ca2+ movement through the pores of some, but not all, P2X channels by measuring the relative permeability of Ca2+ to a reference monovalent cation (called PCa/PM), with the reported values ranging from ∼1 to 4 for different members of the family (for review, see North, 2002). Many of these studies used different extracellular and intracellular concentrations of ions, different values for ion activities, and different algorithms to calculate relative permeability. Thus, it is not possible to directly compare values between studies, and consequently a precise understanding of Ca2+ flux for the P2X family in relation to other channels has been lacking. Here, we used a single, direct and model-independent method and a uniform set of physiological ionic conditions to quantify Ca2+ flux through all known homomeric and heteromeric P2X channels in relation to other transmitter-gated channels. We find that Ca2+ flux ranges from ∼3 to 15% of total current through the P2X pore in a manner that depends on the subunit composition of protein. This corresponds to PCa/PM values between ∼1 and 3 if current follows constant field assumptions (Burnashev et al., 1995).

The main finding of the present study is that ATP-gated channels conduct an unexpectedly large flux of Ca2+ across cell surface membranes at resting membrane potentials in physiological solutions. As a family, P2X channels conduct more Ca2+ on average than do ACh, proton, serotonin, or glutamate-gated channels. Furthermore, the fractional Ca2+ current at the brain forms of P2X channels (P2X2, P2X4, P2X2/6, and perhaps P2X4/6) at ∼6–14% is significantly larger than that of AMPA (∼0.5–3.9%) and kainate channels (∼0.2–2%) (Burnashev et al., 1995), and, in the case of P2X2, similar to that of P2X channels in sympathetic neurons (Rogers and Dani, 1995). Several P2X channels (P2X1, P2X4, P2X2/6 and perhaps P2X4/6) display fractional calcium currents between ∼8 and 15% that are larger than those of α7 nicotinic channels (Fucile et al., 2003) and equal to or greater than distinct NMDA channels at 8–14% (Burnashev et al., 1995). Furthermore, Ca2+ inflow through NMDA channels decreases at potentials more negative than –30 mV because of Mg2+ block of the pore (Burnashev et al., 1995), whereas this does not occur for P2X channels. Thus, it is likely that Ca2+ flux through P2X channels may dominate over NMDA channels at resting membrane potentials when Mg2+ blocks the NMDA channel. Furthermore, our data indicate that, in contrast to nicotinic and glutamate channels, P2X2 channels may not use rings of fixed charge to select Ca2+. Rather, a critical domain (Migita et al., 2001) in the center of the pore influences Ca2+ flux (Fig. 6). Although the precise mechanism of ion selection is unknown, polar amino acids may provide the countercharge needed to partially dehydrate Ca2+ ions in a narrow part of the pore. At present, we do not know if this countercharge is supplied by backbone carbonyl oxygens, as is the case for K+ channels (Doyle et al., 1998), or directly by the side chains themselves. Indeed, the lack of sequence conservation in this domain among the family favors the latter hypothesis (Fig. 7). However, unlike the side chains of the amino acids that constitute the selectivity filter of K+ channels, the side chains of T336, T339, and S340 of the P2X2 channel face into the aqueous environment of the pore (Egan et al., 1998) and therefore are well positioned to influence the flow of ions across the membrane. Different members of the family display a variable Ca2+ flux, and it will be interesting to see whether this range reflects the sequence variability in TM2. Future experiments designed to study the effects of site-directed mutagenesis at homologous sites of other family members are needed before a complete hypothesis about the mechanics of calcium permeability and flux can be presented. Furthermore, it is not apparent in the sequences presented in Figure 7 why the P2X1 and P2X4 channels should have such extraordinarily high Ca2+ fluxes; the explanation may reside at distant sites An obvious place to look would be TM1 because it, like TM2, is thought to line the pore (North, 2002). Alternatively, Ca2+ may be selected by parts of the protein besides the transmembrane domains. The identity of these distant sites may remain hidden until the structure of the channel is solved.

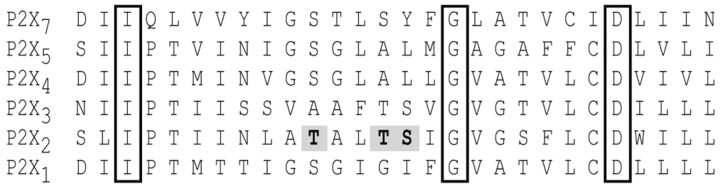

Figure 7.

Sequence alignment of the putative second transmembrane segments of P2X subunits. A stretch of 28 adjoining amino acids thought to span the membrane is shown for each of the six functional homomeric channels. The boxed amino acids are identical in all family members. Mutations of the three shaded amino acids of the P2X2 channel result in changes in Pf%.

The present experiments on molecularly defined channels now call for similar experiments on endogenously expressed P2X channels in brain neurons. From this perspective, we note that previous estimates of Pf% for NMDA channels endogenously expressed in brain neurons (Schneggenburger et al., 1993), and heterologously expressed in HEK293 cells (Burnashev et al., 1995; Watanabe et al., 2002) differ by ∼7%, perhaps suggesting that presently unknown factors in neurons may regulate Pf%. It will be interesting to determine whether a similar situation exists for natively expressed P2X channels. The experiments with native P2X channels in brain neurons are challenging because not all neurons express P2X channels. Moreover, our recent systematic analysis of P2X channel expression in different fields of the hippocampus suggests that P2X channels may be trafficked to nerve terminals and dendrites rather than being expressed in the soma (Khakh et al., 2003). An additional consideration is that it is difficult to discriminate distinct P2X channels from each other because of the paucity of selective agonists and antagonists (Khakh et al., 2001). This problem is heightened by the fact that most neurons contain mRNA for multiple, and in some cases all, P2X subunits (Collo et al., 1996; North, 2002), suggesting that neurons may express mixtures of distinct P2X channels on their surfaces. However, our estimate of Pf% at ∼6% for P2X2 is consistent with that measured previously for natively expressed P2X2-like channels in SCG neurons (Rogers and Dani, 1995). The highest Pf% values for P2X4 and P2X1 at 10–15% channels are also broadly consistent with previous estimates at 15% from medial habenula neurons on the basis of reversal potentials (Edwards et al., 1997). Our demonstration of high Ca2+ flux for the whole P2X channel family offers a molecular interpretation of several physiological responses. Recent elegant studies show profound P2X1 channel-mediated changes in intracellular Ca2+ in smooth muscle cells during fast ATP synaptic transmission (Brain et al., 2002; Lamont and Wier, 2002; Lamont et al., 2003). P2X1 channels are well suited to this task because they are a large source of transmitter-activated Ca2+ flux (Fig. 4). The diverse presynaptic and postsynaptic effects of ATP on synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation (MacDermott et al., 1999; North, 2002) may be explained by variable expression of different P2X subunits and the associated differences in Ca2+ flux. P2X channels are also abundantly expressed in non-excitable cells, including epithelia, astrocytes, and microglia (Inoue, 2002; Schwiebert and Zsembery, 2003), in which the physiological response may be triggered by Ca2+ entry rather than a depolarization. Thus, P2X4 channel activation in epithelial cells results in sustained Ca2+ entry that may trigger Cl– secretion and prove to be of benefit in cystic fibrosis (Zsembery et al., 2003). Interestingly, recent studies show that upregulated P2X channels in microglia may trigger the release of factors such as cytokines and trigger allodynia (Tsuda et al., 2003). It is possible that the trigger for this is likely to be the substantial Ca2+ entry through P2X4 subunit-containing channels. Mutant P2X channels with calibrated Ca2+ fluxes like those reported here could be used to further explore this possibility in vitro and in vivo and possibly in genetic approaches to treat P2X channel-associated pathologies (Tsuda et al., 1999, 2000, 2003). P2X channel subunits have been localized to brain nerve terminals (Vulchanova et al., 1996; Vulchanova et al., 1997; Le et al., 1998; MacDermott et al., 1999) and the periphery of dendritic spines (Rubio and Soto, 2001) by light and electron microscopy. Synaptically released ATP acting on P2X1 channels evokes postsynaptic Ca2+ changes (Brain et al., 2002; Lamont and Wier, 2002; Lamont et al., 2003), and exogenous and endogenously released ATP causes a form of Ca2+-dependent presynaptic facilitation at some interneuron synapses (Khakh et al., 2003). Our data indicating that distinct P2X channels support significant, but variable, Ca2+ flux provides a molecular interpretation of these physiological studies and a rational to determine whether ATP gates a Ca2+ pathway in single dendritic spines that are known to express P2X channels (Rubio and Soto, 2001).

Footnotes

We thank Drs. N. Unwin, D. Bowser, and J. Fisher for comments, L. P. Wollmuth for practical advice on measuring Pf%, and L. Lagnado for loan of equipment. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (UK), a European Molecular Biology Organization Young Investigator Award, the Human Frontier Science Program, and the National Institutes of Health.

Correspondence should be addressed to Baljit S. Khakh, Medical Research Council, Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2QH, UK. E-mail: bsk@mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk.

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5429-03.2004

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/243413-08$15.00/0

References

- Alonzo MT, Chamero P, Villalobos C, Garcia-Sancho J (2003) Fura-2 antagonises calcium-induced calcium release. Cell Calcium 33: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Tsien RW (1987) A novel receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable channel activated by ATP in smooth muscle. Nature 328: 275–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL (2003) Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 517–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brain KL, Jackson VM, Trout SJ, Cunnane TC (2002) Intermittent ATP release from nerve terminals elicits focal smooth muscle Ca2+ transients in mouse vas deferens. J Physiol (Lond) 541: 849–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N (1998) Calcium permeability of ligand-gated channels. Cell Calcium 24: 325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnashev N, Zhou Z, Neher E, Sakmann B (1995) Fractional calcium currents through recombinant GluR channels of the NMDA, AMPA and kainate receptor subtypes. J Physiol (Lond) 485: 403–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collo G, North RA, Kawashima E, Merlo-Pich E, Neidhart S, Surprenant A, Buell G (1996) Cloning of P2X5 and P2X6 receptors and the distribution and properties of an extended family of ATP-gated ion channels. J Neurosci 16: 2495–2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, Pfuetzner RA, Kuo A, Gulbis JM, Cohen SL, Chait BT, MacKinnon R (1998) The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science 280: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FA, Robertson SJ, Gibb AJ (1997) Properties of ATP receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the rat medial habenula. Neuropharmacology 36: 1253–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan TM, Haines WR, Voigt MM (1998) A domain contributing to the ion channel of ATP-gated P2X2 receptors identified by the substituted cysteine accessibility method. J Neurosci 18: 2350–2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer W, Wirkner K, Weber M, Eberts C, Koles L, Reinhardt R, Franke H, Allgaier C, Gillen C, Illes P (2003) Characterization of P2X3, P2Y1 and P2Y4 receptors in cultured HEK293-hP2X3 cells and their inhibition by ethanol and trichloroethanol. J Neurochem 85: 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frings S, Hackos DH, Dzeja C, Ohyama T, Hagen V, Kaupp UB, Korenbrot JI (2000) Determination of fractional calcium ion current in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Methods Enzymol 315: 797–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucile S, Renzi M, Lax P, Eusebi F (2003) Fractional Ca2+ current through human neuronal alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Calcium 34: 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galligan JJ, Bertrand PP (1994) ATP mediates fast synaptic potentials in enteric neurons. J Neurosci 14: 7563–7571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green T, Heinemann SF, Gusella JF (1998) Molecular neurobiology and genetics: investigation of neural function and dysfunction. Neuron 20: 427–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JG, MacDermott AB (1997) Activation of ATP P2X receptors elicits glutamate release from sensory neuron synapses. Nature 389: 749–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He ML, Zemkova H, Koshimizu TA, Tomic M, Stojilkovic SS (2003) Intracellular calcium measurements as a method in studies on activity of purinergic P2X receptor-channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C467–C479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann SH, Terlau H, Stuhmer W, Imoto K, Numa S (1992) Calcium channel characteristics conferred on the sodium channel by single mutations. Nature 356: 441–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugel S, Schlichter R (2000) Presynaptic P2X receptors facilitate inhibitory GABAergic transmission between cultured rat spinal cord dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci 20: 2121–2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K (2002) Microglial activation by purines and pyrimidines. Glia 40: 156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatzke C, Watanabe J, Wollmuth LP (2002) Voltage and concentration dependence of Ca2+ permeability in recombinant glutamate receptor subtypes. J Physiol (Lond) 538: 25–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LH, Kim M, Spelta V, Bo X, Surprenant A, North RA (2003) Subunit arrangement in P2X receptors. J Neurosci 23: 8903–8910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato F, Shigetomi E (2001) Distinct modulation of evoked and spontaneous EPSCs by purinoceptors in the nucleus tractus solitarii of the rat. J Physiol (Lond) 530: 469–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS (2001) Molecular physiology of P2X receptors and ATP signalling at synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci 2: 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Henderson G (1998) ATP receptor-mediated enhancement of fast excitatory neurotransmitter release in the brain. Mol Pharmacol 54: 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Zhou X, Sydes J, Galligan JJ, Lester HA (2000) State-dependent cross-inhibition between transmitter-gated cation channels. Nature 406: 405–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Burnstock G, Kennedy C, King BF, North RA, Seguela P, Voigt M, Humphrey PPA (2001) International Union of Pharmacology. XXIV. Current status of the nomenclature and properties of P2X receptors and their subunits. Pharmacol Rev 53: 107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakh BS, Gitterman DP, Cockayne D, Jones AM (2003) ATP modulation of excitatory synapses onto interneurons. J Neurosci 23: 7426–7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King BF, Townsend-Nicholson A, Wildman SS, Thomas T, Spyer KM, Burnstock G (2000) Coexpression of rat P2X2 and P2X6 subunits in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurosci 20: 4871–4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Wier WG (2002) Evoked and spontaneous purinergic junctional Ca2+ transients (jCaTs) in rat small arteries. Circ Res 91: 454–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont C, Vainorius E, Wier WG (2003) Purinergic and adrenergic Ca2+ transients during neurogenic contractions of rat mesenteric small arteries. J Physiol (Lond) 549: 801–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax P, Fucile S, Eusebi F (2002) Ca2+ permeability of human heteromeric nAChRs expressed by transfection in human cells. Cell Calcium 32: 53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le KT, Villeneuve P, Ramjaun AR, McPherson PS, Beaudet A, Seguela P (1998) Sensory presynaptic and widespread somatodendritic immunolocalization of central ionotropic P2X ATP receptors. Neuroscience 83: 177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermott AB, Role LW, Siegelbaum SA (1999) Presynaptic ionotropic receptors and the control of transmitter release. Annu Rev Neurosci 22: 443–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migita K, Haines WR, Voigt MM, Egan TM (2001) Polar residues of the second transmembrane domain influence cation permeability of the ATP-gated P2X2 receptor. J Biol Chem 276: 30934–30941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C (2001) Physiology, phylogeny, and functions of the TRP superfamily of cation channels. SciSTKE 2001: RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsuka T, Gu JG (2001) ATP P2X receptor-mediated enhancement of glutamate release and evoked EPSCs in dorsal horn neurons of the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 21: 6522–6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicke A, Baumert HG, Rettinger J, Eichele A, Lambrecht G, Mutschler E, Schmalzing G (1998) P2X1 and P2X3 receptors form stable trimers: a novel structural motif of ligand-gated ion channels. EMBO J 17: 3016–3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg W, Illes P (2000) Neuronal P2X receptors: localisation and functional properties. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362: 324–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North RA (2002) Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev 82: 1013–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar LS, Auerbach A (1996) Identification of a high affinity divalent cation binding site near the entrance of the NMDA receptor channel. Neuron 16: 869–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino D, Barabino B, Fucile S, Eusebi F (1998) Ca2+ permeability of mouse and chick nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed in transiently transfected human cells. J Physiol (Lond) 507: 749–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassendren F, Buell G, Newbolt A, North RA, Surprenant A (1997) Identification of amino acid residues contributing to the pore of a P2X receptor. EMBO J 16: 3446–3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves DC, Lummis SC (2002) The molecular basis of the structure and function of the 5-HT3 receptor: a model ligand-gated ion channel [review]. Mol Membr Biol 19: 11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Bian X, DeVries M, Schnegelsberg B, Cockayne DC, Ford AP, Galligan JJ (2003) P2X2 subunits contribute to fast synaptic excitation in myenteric neurons of the mouse small intestine. J Physiol (Lond) 552: 809–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M, Dani JA (1995) Comparison of quantitative calcium flux through NMDA, ATP, and ACh receptor channels. Biophys J 68: 501–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio ME, Soto F (2001) Distinct localisation of P2X receptors at excitatory postsynaptic specializations. J Neurosci 21: 641–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R (1998) Altered voltage dependence of fractional Ca2+ current in N-methyl-d-aspartate channel pore mutants with a decreased Ca2+ permeability. Biophys J 74: 1790–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Zhou Z, Konnerth A, Neher E (1993) Fractional contribution of calcium to the cation current through glutamate receptor channels. Neuron 11: 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM, Zsembery A (2003) Extracellular ATP as a signaling molecule for epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1615: 7–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma G, Stevens CF (1996) Interactions between two divalent ion binding sites in N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 14170–14175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer RH, Rees DC (2002) The alpha-helix and the organization and gating of channels. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 31: 207–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoop R, Thomas S, Rassendren F, Kawashima E, Buell G, Surprenant A, North R (1999) Contribution of individual subunits to the multimeric P2X2 receptor: estimates based on methanethiosulfonate block at T336C. Mol Pharmacol 56: 973–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres GE, Haines WR, Egan TM, Voigt MM (1998) Co-expression of P2x1 and P2x5 receptor subunits reveals a novel ATP-gated ion channel. Mol Pharmacol 54: 989–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Ueno S, Inoue K (1999) Evidence for the involvement of spinal endogenous ATP and P2X receptors in nociceptive responses caused by formalin and capsaicin in mice. Br J Pharmacol 128: 1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Koizumi S, Kita A, Shigemoto Y, Ueno S, Inoue K (2000) Mechanical allodynia caused by intraplantar injection of P2X receptor agonist in rats: involvement of heteromeric P2X2/3 receptor signaling in capsaicin-insensitive primary afferent neurons. J Neurosci 20: RC90(1–5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Mizokoshi A, Kohsaka S, Salter MW, Inoue K (2003) P2X4 receptors induced in spinal microglia gate tactile allodynia after nerve injury. Nature 424: 778–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin N (2000) The Croonian Lecture 2000. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and the structural basis of fast synaptic transmission. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 355: 1813–1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulchanova L, Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Wang J, Buell G, Surprenant A, North RA, Elde R (1996) Differential distribution of two ATP-gated channels (P2X receptors) determined by immunocytochemistry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8063–8067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulchanova L, Riedl MS, Shuster SJ, Buell G, Surprenant A, North RA, Elde R (1997) Immunohistochemical study of the P2X2 and P2X3 receptor subunits in rat and monkey sensory neurons and their central terminals. Neuropharmacology 36: 1229–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe J, Beck C, Kuner T, Premkumar LS, Wollmuth LP (2002) DRPEER: a motif in the extracellular vestibule conferring high Ca2+ flux rates in NMDA receptor channels. J Neurosci 22: 10209–10216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsembery A, Boyce AT, Liang L, Peti-Peterdi J, Bell PD, Schwiebert EM (2003) Sustained calcium entry through P2X nucleotide receptor channels in human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 278: 13398–13408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]