Abstract

Spontaneous synchronous bursting of the CA3 hippocampus in vitro is a widely studied model of physiological and pathological network synchronization. The role of inhibitory conductances during network bursting is not understood in detail, despite the fact that several antiepileptic drugs target GABAA receptors. Here, we show that the first manifestation of a burst event is a cell type-specific flurry of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory input to pyramidal cells, but not to stratum oriens horizontal interneurons. Moreover, GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic input is proportionally smaller in these interneurons compared with pyramidal cells. Computational models and dynamic-clamp studies using experimentally derived conductance waveforms indicate that both these factors modulate spike timing during synchronized activity. In particular, the different kinetics and the larger strength of GABAergic input to pyramidal cells defer action potential initiation and contribute to the observed delay of firing, so that the interneuronal activity leads the burst cycle. In contrast, excitatory inputs to both neuronal populations during a burst are kinetically similar, as required to maintain synchronicity. We also show that the natural pattern of activation of inhibitory and excitatory conductances during a synchronized burst cycle is different within the same neuronal population. In particular, GABAA receptor-mediated currents activate earlier and outlast the excitatory components driving the bursts. Thus, cell type-specific balance and timing of GABAA receptor-mediated input are critical to set the appropriate spike timing in pyramidal cells and interneurons and coordinate additional neurotransmitter release modulating burst strength and network frequency.

Keywords: interneurons, network, GABA, hippocampus, burst, epilepsy

Introduction

Synchronized neuronal activity is an important feature of many regions of the brain under physiological and pathological conditions. In the hippocampus, synchronized bursts are correlated with specific behavioral states and occur during sharp waves (SWs), slow wave sleep, and interictal electrographic activity (interictal spikes) in epileptic animals or humans (Matsumoto and Ajmone-Marsan, 1964; Buzsaki et al., 1983; Suzuki and Smith, 1985, 1988). These rhythms are believed to depend on the local circuitry of the hippocampus and represent an intrinsic pattern of network activity (Traub and Miles, 1991). The expression of specific voltage-dependent conductances (Wong and Prince, 1981; Traub et al., 1991; Migliore et al., 1995) and the abundance of recurrent collateral excitatory connections between CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neurons (MacVicar and Dudek, 1982; Li et al., 1994) are critical features for the initiation of network bursting, which can be preserved in vitro (Traub and Miles, 1991). Indeed, burst firing in a single CA3 pyramidal cell generates a very powerful excitatory drive onto its postsynaptic targets (Miles and Wong, 1984) so that, under conditions of abolished fast GABAergic inhibition, an individual pyramidal neuron can recruit every other pyramidal cell of the CA3 network in a synchronized population burst (Miles and Wong, 1983). However, complete blockade of fast inhibition is not a necessary requirement for burst generation, and other in vitro models of synchronicity exist (Wilson and Bragdon, 1993). Partially restricted synchronized bursts (partial bursts) can be achieved in slices under a variety of different experimental conditions that do not completely abolish GABAergic input. For example, hippocampal slices exposed to elevated concentrations of external potassium engage in rhythmic activity (Rutecki et al., 1985; Traynelis and Dingledine, 1988; Traub and Miles, 1991; McBain et al., 1993), and bursts remain restricted to a portion of the network (Traub and Miles, 1991). During partial bursts, the non-bursting cells of the network display low-frequency oscillations driven by synchronous subthreshold synaptic potentials (Traub and Miles, 1991). Three main variables have been shown to play an important role in modulating this type of network burst in the hippocampus: (1) the specific intrinsic properties of the participating neurons (Chamberlin and Dingledine, 1989; Traub and Miles, 1991; Kamondi et al., 1998; Fricker and Miles, 2001); (2) the strength of glutamatergic input originating from the recurrent collateral positive feedback of the CA3 region (Staley et al., 1998; Bains et al., 1999); and (3) the strength of GABAergic input (Korn et al., 1987; Traub and Miles, 1991; Staley et al., 1998).

In this study, we have combined experimental work with modeling to understand the functions of specific synaptic input to CA3 pyramidal cells and interneurons during synchronous activity. Our results underscore the importance of cell type specificity of GABAA receptor-mediated input for the generation of properly timed and graded bursting in CA3 pyramidal cells and interneurons.

Materials and Methods

Slice preparation. Young rats (Sprague Dawley; age, postnatal days 13-19) were deeply anesthetized using isoflurane and killed by decapitation, in accordance with National Institutes of Health and institutional protocols. The brain was removed quickly and placed into ice-cold cutting solution of the following composition (in mm): 234 sucrose, 28 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 0.5 CaCl2, 7 MgCl2, 7 glucose, 1 ascorbic acid, and 3 pyruvic acid, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, at pH 7.4. The hemisected brain was then glued onto the stage of a vibrating microtome (Leica, Nussloch, Germany), and sections of 400 μm thickness were cut and stored in an incubation chamber for ∼1 hr at room temperature before use. The composition of the artificial CSF (ACSF) in the incubation chamber was (in mm) 130 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 3.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.5 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, and 10 glucose, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2, at pH 7.4. Slices were then transferred, as needed, to the recording chamber and observed under an upright Axioskop microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a 60× water immersion differential interference contrast objective coupled with an infrared camera system (Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN).

Electrophysiological recordings. Conventional whole-cell current-clamp and voltage-clamp techniques were applied using a Multiclamp 700 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Pipettes used for current-clamp experiments (resistance, ∼5 MΩ) were filled with the following solution (in mm): 125 K-methylsulfonate, 10 NaCl, 4 MgATP, 0.3 GTP, 16 KHCO3, and 0.5% biocytin, saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 to a pH of 7.2 and 285-295 mOsm. Voltage-clamp recordings were performed on pyramidal cells and interneurons with electrodes of ∼2 MΩ resistance and filled with the same intracellular solution including 10 mm N-(2,6-dimethylphenylcarbamoylmethyl) triethylammonium bromide to minimize voltage-dependent conductances. Series resistance values were ∼10 MΩ and were not compensated. Dynamic-clamp recordings were performed using a Synaptic Module 1 (SM-1) conductance injection amplifier (Cambridge Conductance, Cambridge, UK) (Robinson and Kawai, 2000; Aradi et al., 2004) and a Multiclamp 700 amplifier (Axon Instruments) in bridge balance mode. The reversal potentials for the excitatory and inhibitory conductance commands were set to 0 and -63 mV, respectively. The electrical circuit of SM-1 computed the current to be injected into the soma of the cell. All recordings were performed at 33-35C° in a modified ACSF, in which the total concentration of KCl was raised to 8.5 mm. In addition, the ACSF used for dynamic-clamp experiments included 2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (20 μm), 2,3-dioxo-6-nitro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline-7-sulfonamide (10 μm), and SR-95531 (gabazine; 12.5 μm) (Tocris Cookson, Ellisville, MO). The temperature of the solution was monitored by a probe in the recording chamber and could be changed by a heating system applied to the perfusing solution before entering the bath (TC344A; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). The estimated reversal potential for GABAA receptor-activated current (EGABAA) was calculated to be -63 mV according to the following equation:

|

where [Cl-]i was 10 mm, [Cl-]o was 141.5 mm,  was 16 mm,

was 16 mm,  was 24 mm, and b was 0.2 (Bormann et al., 1987). However, taking into account that elevated potassium conditions induce a positive shift of fast IPSPs (Korn et al., 1987), we included in our estimated value of EGABAA a shift of ∼3 mV, similar to what was experimentally reported in another study using whole-cell recording conditions (McBain, 1995). High-chloride electrodes were filled with an intracellular solution in which K-methylsulfonate was substituted by equimolar KCl. Under these experimental conditions, the calculated EGABAA was ∼0 mV. Interneurons were selected in the stratum oriens and had bipolar horizontal appearance. Our results were obtained in the CA3c region, which has been reported to be the initiating focus of high-K synchrony in the rat adult hippocampus (Korn et al., 1987). Therefore, assuming a similar situation in the juvenile rat hippocampus, it should be kept in mind that events recorded close to the focus may not mirror those in the follower regions. Cells were usually maintained at a membrane potential of approximately -60 mV to reduce the occurrence of isolated action potentials in the interburst period.

was 24 mm, and b was 0.2 (Bormann et al., 1987). However, taking into account that elevated potassium conditions induce a positive shift of fast IPSPs (Korn et al., 1987), we included in our estimated value of EGABAA a shift of ∼3 mV, similar to what was experimentally reported in another study using whole-cell recording conditions (McBain, 1995). High-chloride electrodes were filled with an intracellular solution in which K-methylsulfonate was substituted by equimolar KCl. Under these experimental conditions, the calculated EGABAA was ∼0 mV. Interneurons were selected in the stratum oriens and had bipolar horizontal appearance. Our results were obtained in the CA3c region, which has been reported to be the initiating focus of high-K synchrony in the rat adult hippocampus (Korn et al., 1987). Therefore, assuming a similar situation in the juvenile rat hippocampus, it should be kept in mind that events recorded close to the focus may not mirror those in the follower regions. Cells were usually maintained at a membrane potential of approximately -60 mV to reduce the occurrence of isolated action potentials in the interburst period.

Data analysis. Data were filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at 10-20 kHz using a Digidata 1322A analog-to-digital board. Analysis was performed using the pClamp (Axon Instruments), Origin (MicroCal, Northampton, MA), Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, WA), Spike 2 (CED, Cambridge, UK), Whole-Cell Program (courtesy of Dr. J. Dempster, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK), and Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) software packages. Analysis of the synchronous events was performed by threshold-triggered alignment of spontaneous events, using one channel as trigger so that the temporal relationships between the two channels were maintained intact. Because it is difficult to determine the exact timing of initiation of a burst, the interevent frequency was calculated from interevent intervals determined by the peaks of the bursts or subthreshold synchronous events. The analysis of the properties of synchronous events was performed on ∼1-3 min duration epochs under the appropriate experimental configuration (baseline control, drug application, or different holding potential). The duration of the epoch was selected based on the frequency of the events in the individual experiment. The decay time constant of the spontaneous EPSC was fitted by a monoexponential or biexponential function, as appropriate, and weighted time constants were used for comparison (Maccaferri et al., 2000). Statistical comparisons were performed using the appropriate t test, one- and two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction. Values are given as mean ± SE.

Determination of arealeft and arearight. To compare the complex kinetics of synaptic conductances between two cells recorded during a burst, we defined two indices (arealeft and arearight) that are related to the degree of similarity of the two recorded waveforms. “Arealeft” was defined as the difference between the areas of the normalized conductances [to -1 normalized unit (n.u.)] between the initial baseline and a reference point that was the peak of the recording in one of the cells. Therefore, arealeft quantifies the kinetics of nonoverlapping synaptic activation during the rising phase. “Arearight” was calculated similarly, but during the decay phase, i.e., from the peak back to the baseline (see left and right insets of Fig. 5, bottom).

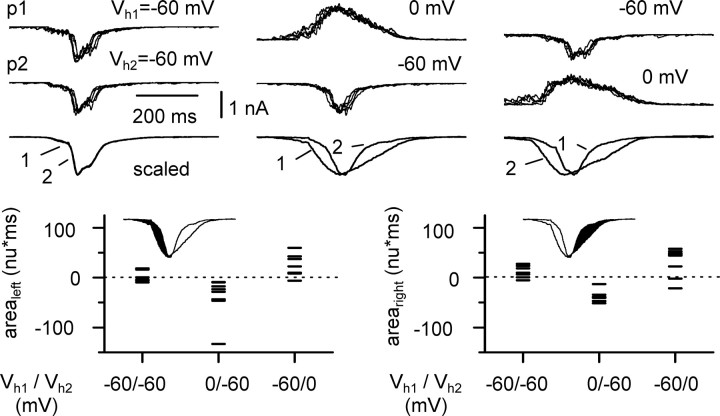

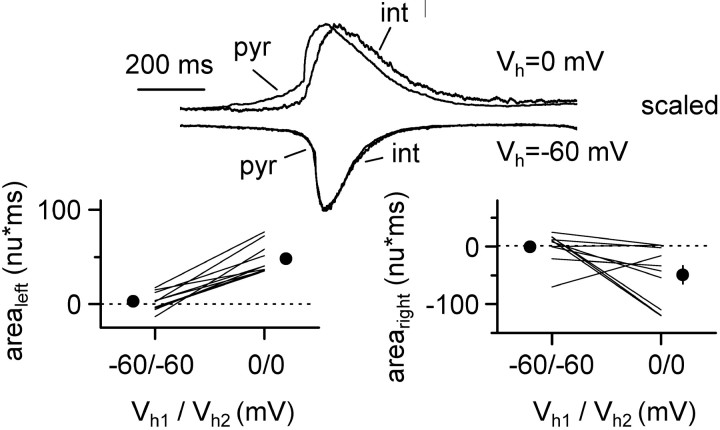

Figure 5.

Dynamic analysis of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents during the same burst cycle. Top, Double voltage-clamp recordings from CA3 pyramidal cells (p1 and p2) held at different membrane potentials (left: Vh1 = -60 mV, Vh2 = -60 mV; middle: Vh1 = 0 mV, Vh2 = -60 mV; right: Vh1 = -60 mV, Vh2 = 0 mV). Five individual sweeps are superimposed in each condition for each cell (p1 and p2). The scaled averages from several traces (left to right: 46, 36, and 38 traces) are shown underneath. Outward currents are reversed for comparison. Bottom, Quantification of the results. The difference between areas of the normalized averages for the left and right side (arealeft and arearight, respectively) are plotted for all the experiments under the different configurations. Notice the difference in the relative timing of the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents in these three configurations.

Modeling CA3 pyramidal cells. The multicompartmental model of bursting CA3 pyramidal cells developed by Traub et al. (1991) was reconstructed (Aradi et al., 2004) with a few modifications. We performed simulations using NEURON software (version 5.4) (Hines and Carnevale, 1997), running on Linux OS. Briefly, the CA3 pyramidal cell model consisted of 19 compartments and six voltage-activated channels: Na+, Ca2+, delayed rectifier K+, Ca2+-dependent afterhyperpolarizing K+, Ca2+- and voltage-dependent K+, and A-type K+ channels. [For the details of the compartmentalization of the model cell and for the kinetics of the channels, see Traub and Miles (1991).] In addition, intracellular calcium dynamics from Migliore et al. (1995) were downloaded from the ModelDB database of SenseLab (http://senselab.med.yale.edu/senselab/modeldb) and incorporated to give a more realistic description of the CA3 pyramidal cell. Some additional adjustments of the parameters of the spontaneously bursting Traub model of the CA3 pyramidal cell were necessitated to achieve stable membrane potential at -60 mV in the absence of synaptic inputs and obtain robust bursting behavior in response to the complex combinations of excitatory and inhibitory drive present in the elevated potassium in vitro model of synchronized network oscillations. These adjustments included the reversal potential for K+ set to -74.5 mV, and the reversal potential for the leak current set to -55.1 mV; for every compartment, the maximum conductance of the delayed rectifier K+ channel was multiplied by 1.45, the maximum conductance of the Ca2+ channel was multiplied by 4.01, the maximum conductance of the Ca2+- and voltage-dependent K+ channel was multiplied by 0.72, and the maximum conductance of the Ca2+-dependent K channel was multiplied by 0.6.

The excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to the CA3 pyramidal cell were simulated using the actual average experimental traces of EPSCs and IPSCs measured in voltage-clamp configuration at -60 and 0 mV, respectively, during the network oscillations. Both the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic conductances were scaled to different maximum conductance values detailed in Results. The IPSC conductance was given to the soma, whereas the EPSC conductance was given to the proximal apical dendrites. The reversal potential for the EPSCs was set to 0 mV, whereas for the IPSCs it was -60 mV.

Visualization of recorded cells and reconstruction. Methods were similar to the ones described by Maccaferri and Dingledine (2002). Briefly, slices were fixed for 1-10 d in a 4% paraformaldehyde PBS solution at 4°C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was removed by incubating the slices in 10% methanol and 1% H2O2 PBS solution. Biocytin staining was processed using an avidin-HRP reaction (Vectastain ABC Elite kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and axon visualization was improved using a PBS solution containing NiNH4SO4 (1%) and CoCl2 (1%). Slices were not resectioned but directly mounted on the slide using an aqueous mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories). Alternatively, they were first dehydrated and then mounted on the slide using a toluene solution (Permount; Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). Slices were observed at 40× magnification and photographed using the AxioVision software package (Zeiss).

Results

Synchronized bursting and effect of GABAA receptor blockade

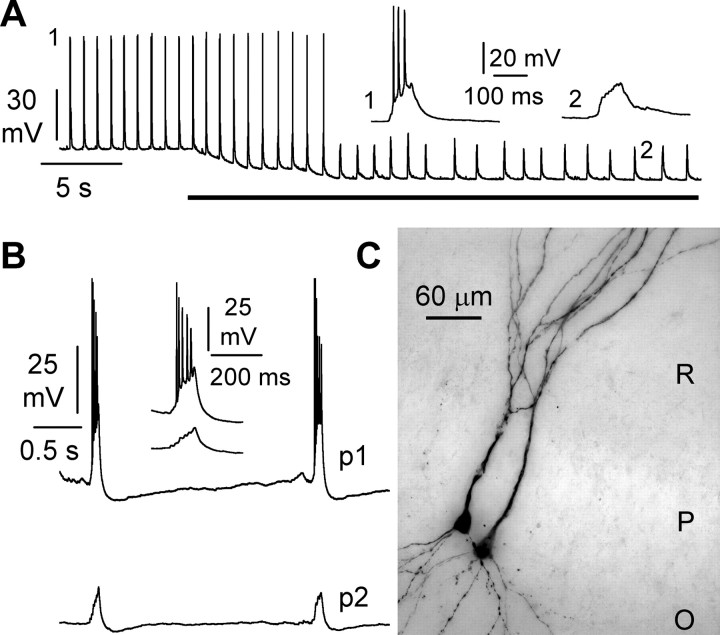

Hippocampal slices were exposed to elevated potassium (8.5 mm) ACSF. Whole-cell recordings from CA3 pyramidal neurons often displayed spontaneous bursts (Fig. 1A). Hyperpolarization of the cell by current injection prevented firing but did not abolish the occurrence of spontaneous events, suggesting that, under our experimental conditions, rhythmic activity was driven by the network and not by intrinsic conductances. This hypothesis was directly tested by recording simultaneously from pairs of neighboring pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1B,C). Double recordings confirmed the occurrence of synchronized events, which could be a combination of bursts in both cells, burst in one cell and subthreshold events in the other (Fig. 1B), or subthreshold events in both cells.

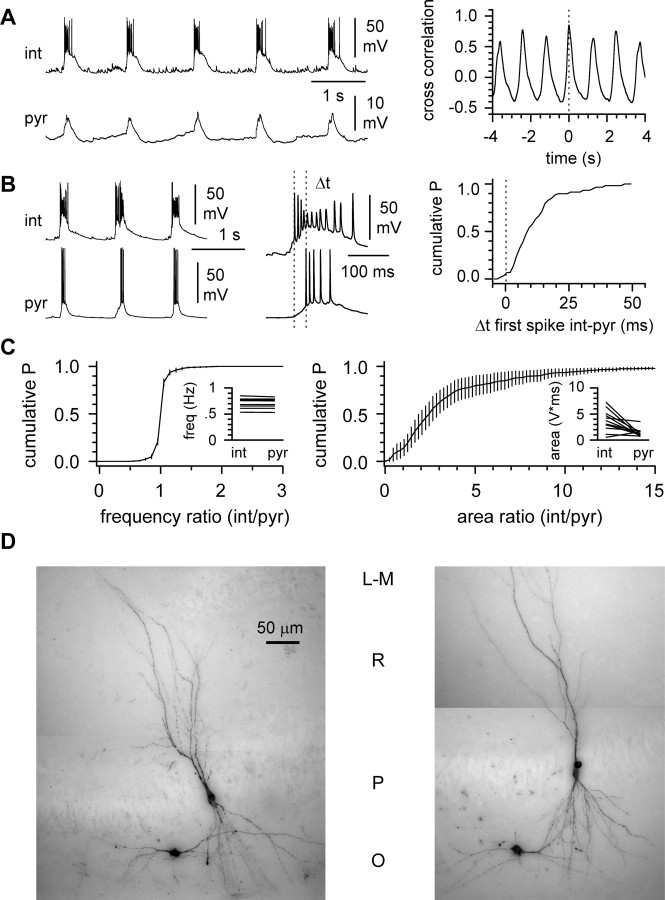

Figure 1.

Synchronous bursting in pyramidal neurons bathed in 8.5 mm external potassium. A, Whole-cell recording from an individual CA3 pyramidal neuron shows repetitive bursting. Hyperpolarization of membrane potential via current injection (black bar) prevents firing and unmasks spontaneous synaptic potentials. The insets show individual events during bursting (1) and after hyperpolarization (2). B, Simultaneous recordings from a pair of CA3 pyramidal cells (p1 and p2). Notice the synchronicity of bursting in one cell with subthreshold synaptic events in the other. C, Visualization of a pair of CA3 pyramidal neurons after recording. Notice the close distance and the overlap of the basal and apical dendritic tree. R, Stratum radiatum; P, stratum pyramidale; O, stratum oriens.

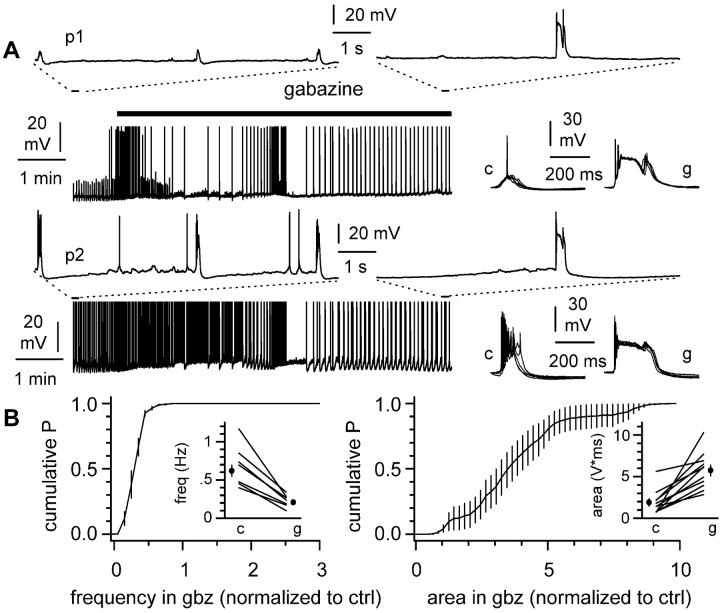

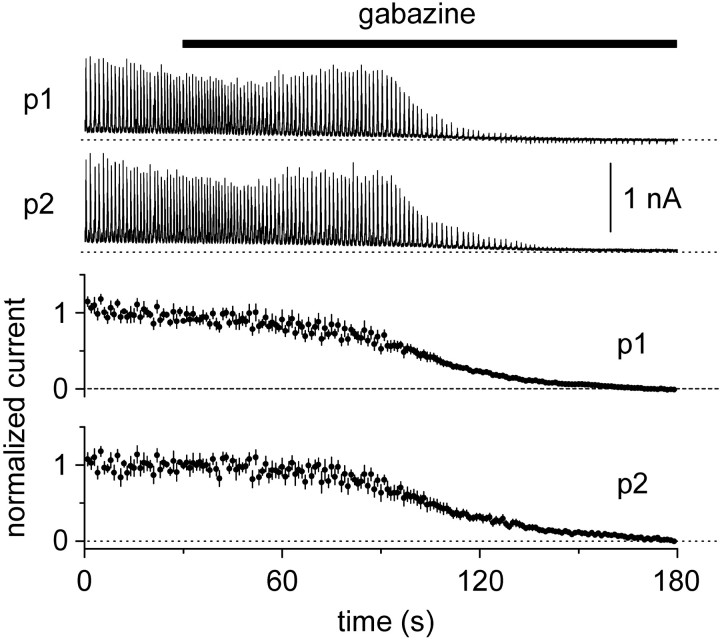

What is the role of GABAA receptor-mediated input during this pattern of activity? We addressed this question by recording from spontaneously active pairs (n = 4) or single CA3 (n = 3) pyramidal neurons before and after the addition of the GABAA receptor antagonist SR-95531 (gabazine; 12.5 μm) (Heaulme et al., 1986). Application of gabazine to the slice triggered a transient period of irregular firing, which was followed by a new steady-state level of network frequency (Fig. 2A). During this newly established steady state, the frequency of spontaneous synchronous events decreased from 0.62 ± 0.07 Hz in control to 0.21 ± 0.02 Hz (p < 0.05; n = 11). When normalized to control conditions, frequency decreased to 0.34 ± 0.03 (n = 11) in the presence of the drug, as shown by the cumulative probability plot of the instantaneous network frequency (Fig. 2B, left). In contrast to this decrease in frequency, the strength of the events, quantified by their area, increased from 1.9 ± 0.4 V⋆msec in control to 5.7 ± 0.6 V⋆msec in gabazine (n = 11; p < 0.05). Normalization to control conditions shows that gabazine increased the area of the events by 3.8 ± 0.6 times (Fig. 2B, right). These results indicate that blockade of fast inhibition promotes multiple effects leading to a change of burst strength and frequency. Slices displaying ictal activity (Dzhala and Staley, 2003) or in which gabazine application triggered cyclic electrographic seizures (Khazipov et al., 2004) without recovering to an interictal-like bursting rhythm were discarded from this analysis.

Figure 2.

Effect of GABAA receptor blockade in the entire slice. A, Simultaneous recording from two CA3 pyramidal neurons (p1 and p2) before and during gabazine (12.5 μm; black bar) application. Notice the initial period of irregular activity, followed by a new steady state. The insets delimited by the dotted lines are expanded versions of the recording. Traces to the right show synchronous events in the two cells aligned for comparison in control conditions (c) and in the presence of gabazine (g). B, Quantification of the results. Left, Cumulative probability plot of the interevent frequency in the presence of gabazine (gbz) calculated after normalization to control (ctrl). The plot shows the average and SE of 11 individual distributions. The inset shows frequency values in control conditions (c) and after the addition of gabazine (g) in individual experiments (lines) and their averages (filled circles). Right, Similar analysis for the strength of the synchronized events, measured as the area of the event.

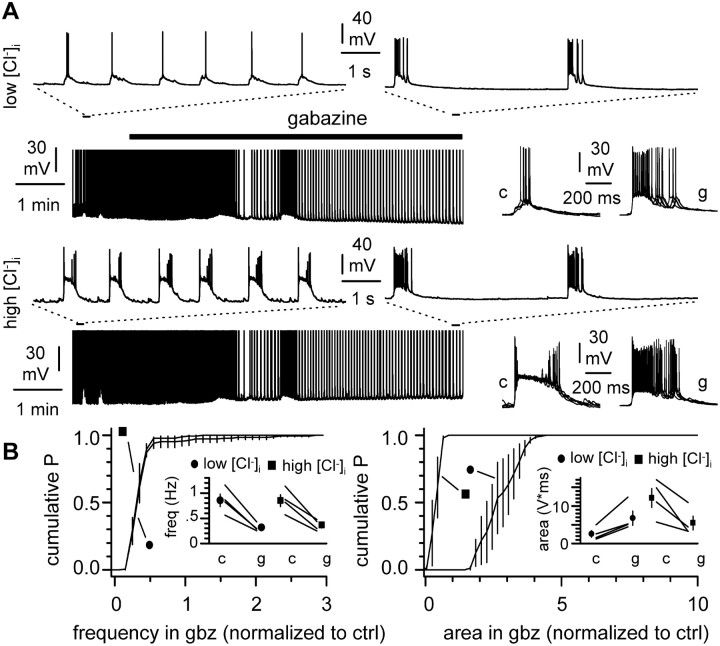

We next designed experiments with the aim of evaluating how activation of GABAA receptors expressed on the surface of the two recorded cells impacted network-driven bursting. We recorded synchronized activity in pairs of cells using different intracellular solutions and then applied gabazine to the slice. In one cell of the pair, we used a standard intracellular recording solution with a chloride concentration of 10 mm (low [Cl-]i). Under this condition, EGABAA was approximately -60 mV. The other neuron of the pair was recorded with a high-chloride concentration intracellular solution (135 mm; high [Cl-]I; estimated EGABAA, ∼0 mV). We reasoned that the different driving force for GABAA receptor-mediated currents in the two recorded neurons would affect synchronized activity that is modulated directly by receptors expressed in the two recorded cells. In contrast, network functions controlled by GABAA receptors expressed in the rest of the network would remain similar. In addition, application of gabazine should have opposite effects on functions mediated primarily by the receptors located on the two recorded cells.

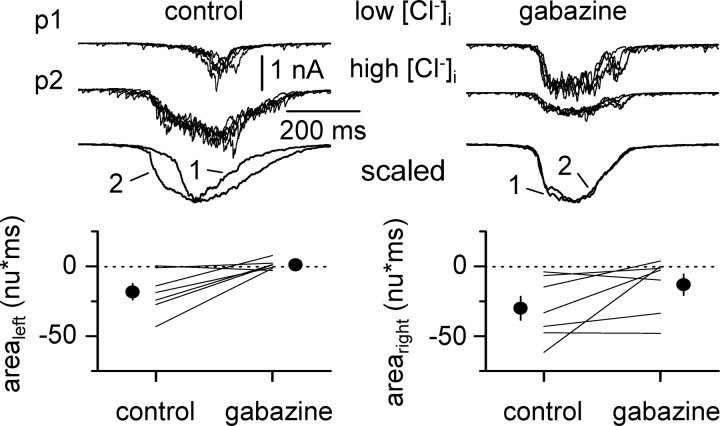

Before gabazine application, the frequency of network-driven events was identical under the two recording configurations (0.85 ± 0.12 Hz in low [Cl-]i vs 0.85 ± 0.12 Hz in high [Cl-]i; n = 4; p > 0.05). However, we found that events were larger in the cells recorded with the high-chloride solution (Fig. 3A). The area of the synchronous events under low-versus high-chloride recording conditions was 2.6 ± 0.9 versus 12.1 ± 2.5 V⋆msec, respectively (n = 4 double recordings; p < 0.05). Gabazine application decreased the frequency of synchronous events in both cells to a similar degree. Network frequency decreased from 0.85 ± 0.12 Hz to 0.32 ± 0.03 Hz (n = 4; p < 0.05) in cells recorded with low-chloride solutions and from 0.85 ± 0.12 Hz to 0.36 ± 0.05 Hz (n = 4; p < 0.05) in cells recorded with high-chloride solution (Fig. 3B, left). Normalization to control reveals that frequency decreased to 0.38 ± 0.03 in low-chloride versus 0.43 ± 0.04 in high-chloride recording conditions (n = 4; p > 0.05). Gabazine-induced modulation of the strength of network-driven events, however, was clearly dissociated by the two different recording conditions (Fig. 3B, right). Gabazine increased the area of the synchronous events recorded with low-chloride electrodes from 2.6 ± 0.8 V⋆msec to 6.8 ± 1.9 V⋆msec (n = 4; p < 0.05; corresponding to an increase of 2.82 ± 0.35 after normalization), whereas a decrease of burst strength was observed in the cell recorded with a high-chloride pipette. Under these latter conditions, the area of the synchronized events decreased from 12.1 ± 2.5 V⋆msec to 5.5 ± 1.8 V⋆msec (n = 4; p < 0.05; corresponding to a decrease of 0.46 ± 0.10 after normalization). In conclusion, these first sets of experiments (Figs. 2, 3) indicate that GABA release occurs during network oscillations and can powerfully activate GABAA receptors in the slice, which play an important role in regulating burst strength and frequency.

Figure 3.

GABAA receptor-mediated network modulation in control versus chloride-loaded neurons. A, Simultaneous activity of pyramidal cells recorded with a low-chloride (10 mm) and a high-chloride (135 mm) whole-cell solution (low [Cl-]i and high [Cl-]i: top and bottom traces, respectively). Insets above the continuous traces show parts of the same recordings at a magnified temporal scale. Notice the stronger bursts in the cell recorded with the high-chloride solution. Gabazine application (12.5 μm; black bar) reduces the frequency of the bursts without affecting the synchronicity of the events. Traces to the right show synchronous events in the two cells aligned for comparison in control conditions (c) and in the presence of gabazine (g). B, Quantification of the results obtained in four double recordings. Left, Average cumulative probability distribution of the frequency in gabazine (gbz) normalized to control conditions (ctrl). The actual values of the individual experiments (lines) and their averages (filled symbols) are shown for in the inset in control (c) and gabazine (g). Filled circles indicate results from cells recorded with low-chloride intracellular solution, whereas filled squares indicate results from chloride-loaded neurons. The right panel shows the cumulative probability distribution plot of the normalized areas in gabazine for the two recording conditions. The averages and actual values for individual experiments are shown in the inset in control (c) and after gabazine (g) application.

Interneuron activity during network bursts

Synaptic release from presynaptic terminals of interneurons is the main source of GABA acting on postsynaptic receptors (Buhl et al., 1994; Freund and Buzsaki, 1996) It has been shown that during elevated potassium-induced network activity, stratum oriens horizontal interneurons are driven by glutamatergic periodic inward currents (McBain, 1995). However, the temporal relationship between these interneurons and pyramidal cell firing has not been explored in detail. Because GABAA receptor-mediated input modulates bursts in pyramidal cells, we assumed that interneurons must also be active. To verify this hypothesis, we recorded simultaneously from horizontal stratum oriens interneurons and pyramidal cells (Fig. 4A). Horizontal stratum oriens interneurons are easily recognizable in a living slice and can target several different postsynaptic domains of pyramidal cells (Maccaferri et al., 2000). Interneurons displayed strong burst generation in 10 of 12 recordings and subthreshold synaptic oscillations in the remaining two. In all cases, events were strongly synchronized to pyramidal cell activity. In four cases, suprathreshold activity was concomitantly observed in both cells. Initiation of interneuron firing always preceded and outlasted action potential generation in the pyramidal cells (Fig. 4B), similarly to what has been reported in human epileptic tissue and normal primate slices (Schwartzkroin and Haglund, 1986) As shown in Figure 4C, the frequency of network events was virtually identical in pyramidal cells and interneurons (0.81 ± 0.07 vs 0.82 ± 0.07 Hz, respectively; n = 12; p > 0.05), but the strength of the synchronized events was markedly different (1.4 ± 0.2 V⋆msec in pyramidal cells vs 3.7 ± 0.2 V⋆msec in interneurons; n = 12; p < 0.05). The mean ratio of the interevent frequency in interneurons over pyramidal cells was 1.0 ± 0.0 (n = 12), and the mean ratio of the area was 3.7 ± 0.9 (n = 12). The tight synchronization between interneurons and pyramidal cells and the fact that we consistently recorded from spatially close neurons (Fig. 4D) suggest that the recorded cells were mostly driven by the same set of afferent fibers. These results also indicate that stratum oriens interneurons are activated more powerfully than pyramidal cells during synchronized bursting and that spike timing within a bursting cycle is different between principal cells and interneurons. The observed spike timing in interneurons would predict that synaptic inhibitory activity should precede and even outlast excitatory inputs to the postsynaptic targets of the recorded cells.

Figure 4.

Synchronicity between interneurons and pyramidal cells. A, Left, Double recording from an interneuron (int) and a pyramidal cell (pyr). Note the weaker (subthreshold) activity in the pyramidal cell. The cross-correlation diagram on the right shows the synchronicity of the events in the two cells. B, Left, Simultaneous recordings displaying synchronous bursting in interneurons and pyramidal cells. The middle panel shows individual bursts at an enlarged time scale. Note that bursting starts earlier in the interneuron (the vertical dotted lines are aligned with the first spikes of the bursts). The cumulative distribution of the time difference (Δt) between the first spikes in the two cells is shown in the right panel for another pyramidal cell-interneuron recording. C, Quantification of the recordings. Left, The slope of the average cumulative distribution of the interevent frequency is very steep near 1, as expected from coherent activity. The frequency values for the two different cell types (int, interneurons; pyr, pyramidal cells) in individual experiments are shown in the inset. Right, Average cumulative distribution of the ratio of the area of events recorded in the two cell types indicating stronger current-clamp activity of interneurons. The inset shows the raw values for the two cell types. D, Visualization of recorded cells. Note the stereotypical appearance of the cells selected for the recordings. L-M, Stratum lacunosum-moleculare; R, stratum radiatum; P, stratum pyramidale; O, stratum oriens.

Synaptic dynamics of GABAA-mediated versus excitatory input in pyramidal neurons

We performed a set of experiments with the aim of dissecting out the dynamics of fast inhibitory and excitatory conductances during the same bursting cycle in pyramidal cells (Fig. 5). By effectively reducing inhibitory or excitatory currents in one cell by voltage clamping at the relevant reversal potential, we could compare the kinetics of the isolated GABAergic or glutamatergic input and their temporal relationship. When two neighboring cells were held at -60 mV, excitatory burst currents were overlapping (Fig. 5, top left inset) as determined by the values of arealeft and arearight (see Materials and Methods for definitions of arealeft and arearight). The calculated values from eight double recordings were 2.0 ± 3.6 n.u.⋆msec (arealeft) and 10.9 ± 4.0 n.u.⋆msec (arearight). Next, we evaluated the dynamics of GABAA receptor-mediated conductances in one cell of the pair held at 0 mV (which is the assumed reversal potential for excitatory conductances), while recording the other cell at -60 mV (Fig. 5, top middle inset). Under this configuration, the values for arealeft and arearight were -38.9 ± 14.3 n.u.⋆msec and -39.0 ± 4.1 n.u.⋆msec, respectively (n = 8; p < 0.05), demonstrating that when close to the reversal potential of excitatory transmission, the inhibitory component temporally precedes and outlasts the excitatory waveform in the other neuron. We then switched configuration again, so that this time -60 mV was applied to the cell previously held at 0 mV and vice versa (Fig. 5, top right inset). This manipulation reversed the values for arealeft and arearight to 22.7 ± 7.8 n.u.⋆msec and 31.2 ± 10.2 n.u.⋆msec (n = 8; p < 0.05). We concluded that the time course of fast inhibitory and excitatory conductances activated during a burst in pyramidal cells is indeed different. In particular, inhibitory conductances have a longer duration and precede and outlast the excitatory waveforms. To verify that currents recorded at 0 mV were mediated by GABAA receptors, in seven double recordings we applied gabazine and found that the spontaneous outward currents recorded at 0 mV were completely abolished (Fig. 6). We further corroborated these results in another series of experiments by recording from a pair of cells both held at -60 mV. However, one cell of each pair was patched with a low-[Cl-]i pipette (10 mm), whereas the second cell was recorded with a high-[Cl-]i electrode (135 mm). We reasoned that the cell recorded with the low-[Cl-]i pipette would reveal the time course of the excitatory conductances only, whereas the second neuron recorded with the high-[Cl-]i electrode would reveal a combination of the dynamics of both excitatory and inhibitory conductances, weighted by their strength. As shown in Figure 7, the kinetics of the currents were clearly different in the two cells, suggesting earlier activation and later termination of GABAA-mediated conductances. Indeed, the kinetic difference between the time courses of the synaptic currents in the two recorded neurons was significantly reduced when gabazine was applied. We quantified this difference by calculating the arealeft and arearight indices for the cells recorded with the high- and low-[Cl-]i electrode. Arealeft switched from -18.2 ± 5.7 n.u.⋆msec in control solution to 1.1 ± 1.3 n.u.⋆msec in the presence of gabazine (n = 7; p < 0.05), whereas arearight changed from -30.1 ± 8.4 n.u.⋆msec to -13.1 ± 7.5 n.u.⋆msec, after application of the drug (n = 7; p < 0.05), suggesting that the earlier activating and later decaying waveform was mediated by GABAA receptors.

Figure 6.

Synchronized currents recorded at Vh = 0 mV are mediated by GABAA receptors. The top traces show a simultaneous voltage-clamp recording from two pyramidal cells. The black bar indicates the timing of gabazine (12.5 μm) application. Bottom, Summary plots constructed from seven double recordings. Currents were normalized to the first 30 sec in control conditions.

Figure 7.

Dynamics of excitatory and inhibitory burst currents in cells recorded with different levels of intracellular chloride. Top, Double voltage-clamp recordings at holding potentials Vh = -60 mV in cells impaled with a standard (10 mm; low [Cl-]i) and chloride-loaded (135 mm; high [Cl-]i) electrode. Traces are shown in control ACSF (left) and after addition of gabazine (12.5 μm; right). Notice that gabazine reduces the difference in synaptic dynamics. Five individual sweeps and the averages of 54 and 37 traces in control conditions and after the addition of gabazine are shown. The bottom panels show the summary quantifications for arealeft and arearight in control ACSF versus gabazine. Individual experiments are shown by lines and averages by the black circles.

Direct effect of fast inhibitory conductances on pyramidal cells during a bursting cycle

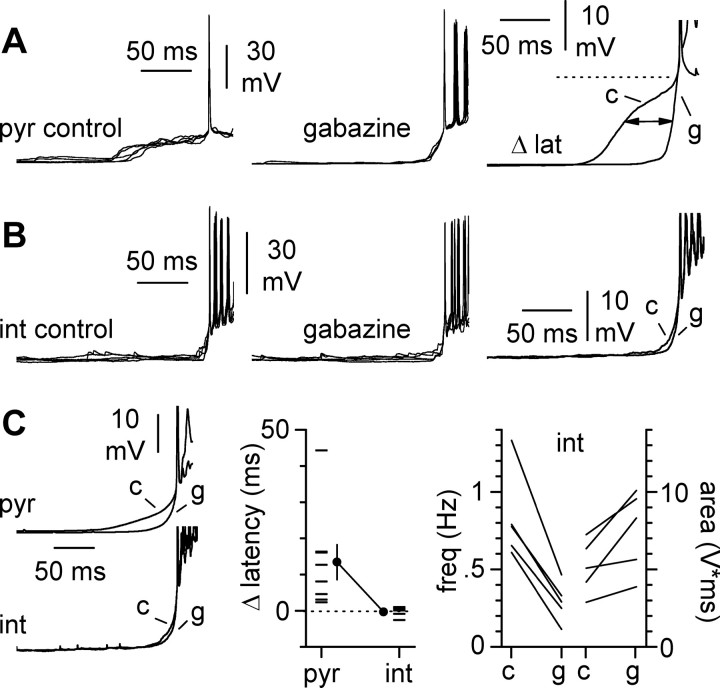

The specific dynamics of fast inhibitory and excitatory conductances during a burst suggest that the latency to the first spike during a synchronous cycle may be controlled by GABAA receptor-mediated conductances. To address this question, we compared the latency to the first spike in the absence and in the presence of gabazine (Fig. 8). We quantified the effect of gabazine on the latency to the first spike by measuring the time difference (Fig. 8, Δ latency) of the point on the trace located halfway from baseline to spike threshold. Spike threshold was defined as the membrane potential level when dV/dt exceeds 10 V/sec (Fricker and Miles, 2001). Gabazine had a prominent effect on the latency to the first spike in pyramidal cells, as expected (Δ latency was 13.4 ± 4.8 msec; n = 8) (Fig. 8A). In contrast, no effect of gabazine could be found on Δ latency in five individually recorded interneurons (-0.3 ± 0.6 msec; n = 5; p < 0.05). As a positive control to show that gabazine had an effect on the slices in which interneurons were recorded, we measured the changes in frequency and area of interneuronal bursts. As expected, and similarly to what is shown in Figures 2 and 3, the frequency of bursts in interneurons decreased from a control value of 0.83 ± 0.13 Hz to 0.29 ± 0.06 Hz (p < 0.05; n = 5) (Fig. 8C) in the presence of gabazine. In addition, gabazine increased the area of the bursts from 5.1 ± 0.8 V⋆msec to 7.5 ± 1.2 V⋆msec (p < 0.05; n = 5) (Fig. 8C). These data suggest that early inhibition during a burst plays a role in regulating spike timing in pyramidal cells but not in interneurons. It is, however, important to note that gabazine application in the slice is likely to trigger a variety of indirect effects (see also Discussion). For example, the augmented area of the events recorded in interneurons could depend on the increased bursting in pyramidal neurons and not necessarily be the result of direct blockade of fast inhibition on the interneurons themselves.

Figure 8.

Cell type-specific effect of gabazine (12.5 μm) on the latency to the first spike of a burst. A, Gabazine changes the early phase of synchronous bursts in pyramidal cells. Five spontaneous bursts are aligned on the first spike. Notice the slow synaptic ramp in control conditions (left) and the rapid acceleration in the presence of the drug (middle). Averages from 49 traces in control and 38 traces in the presence of gabazine are superimposed (right) to show the difference in the latency to the first spike caused by blockade of inhibition. The double arrow indicates the latency difference (Δ lat) measured as the time shift of the point located halfway from baseline to threshold (dotted line) in control (c) versus gabazine (g). B, A similar analysis conducted in stratum oriens horizontal interneurons yields different results. The latency to the first spike remains very similar in the absence (left) and in the presence (middle) of the drug. The right panel shows the superimposed averaged traces in control and in the presence of gabazine (38 and 43 traces, respectively). C, Summary plots. Left, Average traces for eight pyramidal cells and five interneurons show the cell type specificity of the effect of gabazine on the initial part of a burst leading to the first spike. Middle, the graph shows the difference in latency to the first spike caused by gabazine for the two cell types. Right, As a positive control, the effect of gabazine on interneuron burst frequency and area is plotted for each individual experiment, indicating that the drug was modulating the network, as expected.

Next, we took advantage of computational modeling techniques, in which manipulations do not suffer from these indirect effects. We used the time course of the voltage-clamp recordings shown in Figure 5 to simulate GABAA receptor-mediated (gIPSC) and fast excitatory (gEPSC) conductances. We fed gIPSC and gEPSC to a model of a CA3 pyramidal cell and evaluated the role of the ratio between gIPSC and gEPSC on the threshold and timing for burst initiation. As shown in Figure 9A, increasing the relative contribution of gIPSC over gEPSC converted full bursts to subthreshold synaptic potentials and regulated spike timing within a burst. Full-blown bursts produced by the simulations were similar, but shorter than experimental records (Fig. 9A). This is probably because of the fact that gEPSC was estimated from voltage-clamp recordings at -60 mV, in which the contribution of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) to synaptic conductance is minimal, if not completely absent (Hestrin et al., 1990). This result is also consistent with the notion that NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission is essential for seizure generation in the CA1 area but is not required for interictal-like bursts in the CA3 hippocampal subfield (Traynelis and Dingledine, 1988) The gIPSC/gEPSC ratio was crucial in setting the spike timing within the burst (Fig. 9B): this effect was observed for all the different values of conductances tested and therefore is likely to reflect a general network mechanism (Traub and Miles, 1991).

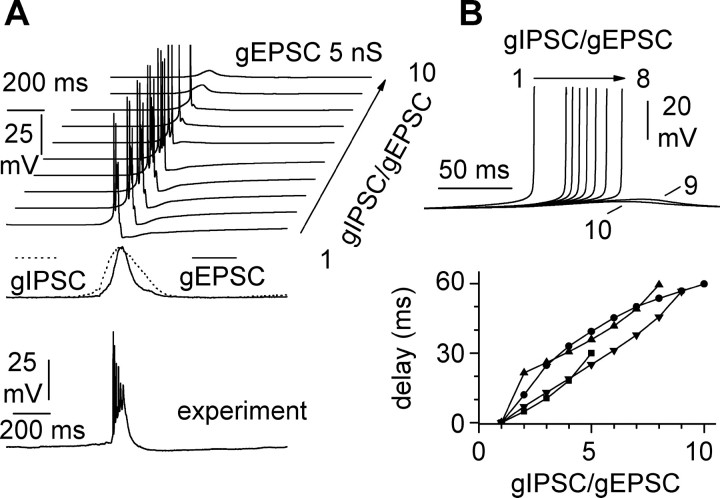

Figure 9.

Simulation of the effect of excitatory and inhibitory conductances injected in a model CA3 pyramidal neuron. A, The transition from subthreshold oscillatory synaptic activity is crucially regulated by the ratio gIPSC/gEPSC. This ratio was increased from 1 to 10 while keeping gEPSC 5 nS throughout this set of simulations. The time course of the inhibitory (gIPSC) and excitatory (gEPSC) conductances was derived from the averages shown in Figure 5 and is shown for reference below the simulations. An experimental burst trace (experiment) is also shown for comparison. B, Timing of the first spike in the burst depends on the level of inhibition relative to excitation. Traces in the top panel are simulated responses of the CA3 model cell to a gEPSC of 5 nS paired with a gIPSC ranging from 5 to 50 nS. For clarity, only the upstroke of the first spike is shown. Bottom, Effect of gIPSC/gEPSC on the timing of the first spike for different levels of gEPSC [2.5 nS (squares), 5 nS (upward triangles), 10 nS (downward triangles), and 20 nS (circles)]. Notice that the latency to the first spike is increased with larger ratios in all the tested conditions. The spike timing for a gIPSC/gEPSC of 1 is taken as the reference point at each conductance level, and the relative delay is plotted at the various gIPSC/gEPSC ratios.

Synaptic events in pyramidal neurons and stratum oriens horizontal interneurons during network activity

Network dynamics are determined by the integrated pattern of activity of all its cellular components. The results shown in Figure 8 suggest that the burst initiation may be differently regulated in pyramidal cells versus interneurons. Therefore, we decided to approach this question directly by recording and comparing the dynamics of synaptic inputs on pyramidal cells versus stratum oriens horizontal interneurons with respect to both of their excitatory and inhibitory components. First, we studied spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) occurring during interburst intervals (Fig. 10A, double arrow). sEPSCs recorded on pyramidal cells and interneurons held at -60 mV showed clear differences, similar to what has been reported for evoked EPSCs in quiescent slices (Hestrin et al., 1990; Sah et al., 1990). From a total of 12 double recordings, the 10-90% rise times of these events were 2.2 ± 0.2 msec in pyramidal cells versus 0.6 ± 0.1 msec in interneurons (p < 0.05), the decay time constant (τ) was 8.9 ± 0.5 versus 3.6 ± 0.7 msec (p < 0.05), and the charge transfer was 0.50 ± 0.03 versus 0.17 ± 0.01 pC (p < 0.05), respectively. In contrast, excitatory inputs during burst activity (bEPSC) were not significantly different between the two cell types. Despite a larger variability of the events recorded in the interneuron population, no statistical differences could be found in the mean charge transfer (52 ± 6.7 pC in pyramidal cells vs 82 ± 28 pC in interneurons; p > 0.05) (Fig. 10B, left) or time course (see below) (Fig. 11). Taken together, these results indicate that, despite differences in sEPSC unitary components, the longer duration of bEPSCs filters out their kinetic differences. In addition, the specific integrative properties of pyramidal cells and interneurons might contribute to produce a similar excitatory input, which explains the tight synchronicity of their activation, as shown in Figure 4. Next, we analyzed burst events under voltage-clamp configuration at Vh = 0 mV (bIPSCs) (Fig. 10B, right) in pyramidal cells and interneurons. bIPSCs were larger in pyramidal cells when compared with interneurons (the charge transfer measured was 167 ± 11 vs 31.4 ± 5.8 pC; respectively; n = 10; p < 0.05). Given the importance of the gIPSC/gEPSC ratio we have shown before (Fig. 9), it is important to note that the ratio of the average bIPSC charge transfer over the average charge transfer of bEPSCs was larger in pyramidal cells than interneurons (∼3 in pyramidal cells compared with ∼0.4 in interneurons). In addition, a barrage of synaptic activity increasing in a ramp manner often preceded the main event in pyramidal cells, whereas such activity could not be observed in interneurons (Figs. 10B, right; 11).

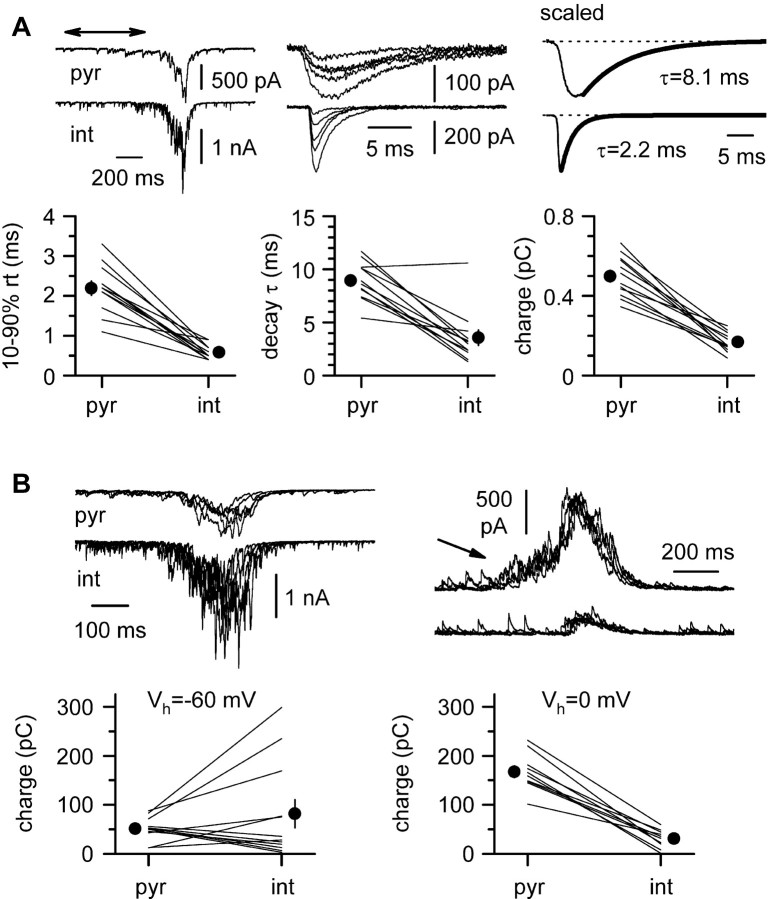

Figure 10.

Spontaneous synaptic currents during interburst intervals and burst cycles. A, Properties of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) recorded in the interburst periods. The top left panel shows an example of the interburst region (double arrow) chosen for the analysis during a simultaneous pyramidal cell (pyr) interneuron (int) recording. The top middle panel shows overlapped sample sweeps from both cell types. Top Right, Monoexponential fit of the decay phase of scaled sEPSCs in a pyramidal cell and in an interneuron. Note the faster kinetics of the sEPSCs recorded in the interneuron. The bottom panels display the quantification of the 10-90% rise time (rt), decay time constant (τ), and charge transfer for 12 double recordings. Individual results are indicated by a line and averages by the filled circle. B, Spontaneous compound EPSCs and IPSCs during synchronized burst activity (bEPSCs and bIPSCs) in pyramidal cells and interneurons. Left, bEPSCs in pyramidal cells (pyr) and interneurons (int). Despite a larger variability in interneurons, the summary plot at the bottom does not show significant differences of the mean charge transfer. Lines indicate individual experiments, and circles show the average of the results. Right, bIPSCs are different between pyramidal cells (top traces) and interneurons (bottom traces). Notice the flurry of activity at the beginning of the event in the pyramidal cells (arrow) but not in the interneurons. The summary plot at the bottom shows that the inhibitory charge transfer is larger in pyramidal cells than in interneurons.

Figure 11.

Cell type specificity of fast excitatory and inhibitory synaptic input during a burst cycle. Top, Normalized averaged waveforms of synchronized activity recorded in pyramidal cells (pyr; n = 10) and interneurons (int; n = 10) at Vh = 0 mV (top traces) and Vh = -60 mV (bottom traces) Notice the specificity of the time course only for the inhibitory component and the similarity of the excitatory waveform. Bottom, Quantification of the cell type specificity of synaptic dynamics by comparing normalized waveforms recorded in pyramidal cells and interneurons. The subtracted area in the initial part (from baseline to peak of the interneuron recording: arealeft) and final part (from peak of the interneuron recording back to baseline: arearigth) of the normalized averaged current traces is voltage dependent.

The differences of the dynamics of the synaptic inputs during a burst were dependent on the holding membrane potential, which would isolate excitatory and inhibitory components (Fig. 11). When both cells were held at -60 mV, the time course of the recorded conductances was very similar. Under this configuration, the difference between the areas delimited by the normalized waveforms in the two cell types was as follows: arealeft, -2.7 ± 3.1 n.u.⋆msec; arearight, 0.2 ± 8.7 n.u.⋆msec; n = 10. Changing the holding potential in both cells to 0 mV caused a significant increase of the area resulting from the subtraction of the normalized waveforms. Under this experimental condition, arealeft and arearight were 48 ± 5 and -49 ± 16 n.u.⋆msec, respectively (n = 10; p < 0.05). These results indicate that inhibitory input during a bursting cycle is temporally cell type specific and differs between pyramidal cells and interneurons.

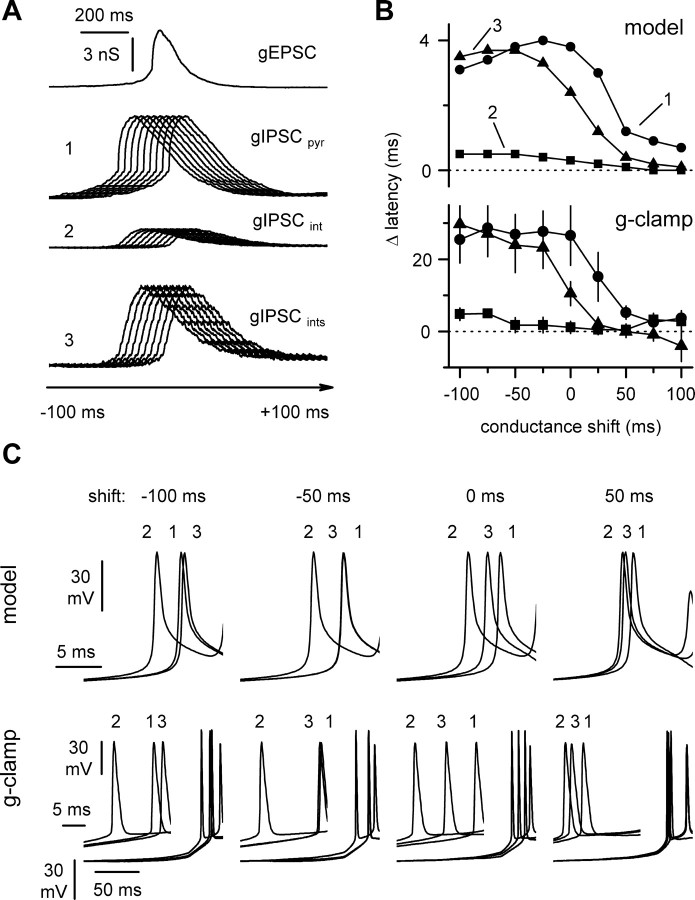

To explore the significance of cell type-specific fast inhibition, we ran simulations and injected conductances derived from actual voltage-clamp recordings to a model pyramidal cell at different time windows (Fig. 12). We tested the effect of cell type specificity of fast GABAergic conductances on the timing of the first spike in a burst (Fig. 12A). As shown in Figure 12, B and C, the prediction of these simulations was that both the strength and kinetics contribute to delay action potential initiation within a burst in pyramidal neurons. Dynamic-clamp experiments performed in pyramidal cells fully confirmed these predictions: feeding an inhibitory conductance derived from pyramidal cells had a different effect on the latency to the first spike when compared with waveforms derived from interneurons (Fig. 12B, bottom) (data from nine pyramidal cells under dynamic-clamp conditions; p < 0.05).

Figure 12.

Modeling and dynamic-clamp analysis of the regulation of burst spike timing in pyramidal cells by cell type-specific inhibitory input. A, The current waveforms shown in Figure 11 were converted to conductances [i.e., recordings at Vh = -60 mV in the pyramidal cells were converted to excitatory conductances (gEPSCpyr), and recordings at 0 mV in pyramidal cells and interneurons were converted to inhibitory conductances (gIPSCpyr and gIPSCint, respectively)]. gEPSCpyr (5 nS peak amplitude) was either paired with gIPSCpyr (1) or gIPSCint (2), and they were shifted in 25 msec steps relative to gEPSC. The ratio of the area delimited by the waveforms was chosen to reflect the ratio of the average charge transfer shown in Figure 10. The ratio of the area of IPSCpyr over gEPSCpyr was 3, and the ratio of gIPSCint over gEPSCpyr was 0.4. To isolate the effect of the different kinetics, gIPSCint was scaled to 3, resulting in gIPSCints. B, Top, Pairing gEPSCpyr with gIPSCpyr (1), gIPSCint (2), or gIPSCints (3) resulted in a different spike timing of the first action potential of the simulated burst. The summary graph relates the difference in the latency of the first spike in the burst in reference to simulations without any inhibitory waveform. Bottom, Same summary graph obtained from dynamic-clamp experiments performed on CA3 pyramidal neurons (n = 9). Notice the similarity of the plots. In a few cases, when inhibition suppressed spiking, the peak of the subthreshold response was used in place of the timing of the action potential. C, Simulated and actual traces for time shifts of -100, -50, 0, and 50 msec. The effect was maximal in the time windows reflecting the experimental results of Figure 5. Notice that coupling gEPSCpyr with gIPSCint results in anticipated firing. Notice also that, despite the fact that the same area is delimited by gIPSCpyr and gIPSCints, the first spike of the burst tends to occur earlier when the interneuron waveform is applied.

Discussion

In this study, we have answered three fundamental questions related to network bursting under conditions of preserved fast GABAergic inhibition: (1) What is the role of GABAA receptors expressed on CA3 pyramidal cells during network bursting? (2) What is the natural pattern of activation of fast inhibitory and excitatory conductances during a burst cycle? (3) Does cell type-specific inhibition play any role in the regulation of network bursting?

Direct role of GABAA receptors on CA3 pyramidal cells during network bursting

We have taken advantage of the whole-cell configuration to control the level of chloride in the recorded cells and manipulate the reversal potential of GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Our data demonstrate that GABAA receptor activity in the recorded neurons affects the strength of the burst but not the synchronicity with the rest of the network. In agreement with this result, computational modeling shows that the ratio of inhibitory over excitatory conductances acts as a gate to allow bursting versus subthreshold oscillatory activity. Therefore, a convergence of results indicates that GABAA receptors expressed on pyramidal cells can powerfully modulate network bursting. Voltage-clamp analysis of synchronicity in adult animals, however, has suggested a much smaller role for fast GABAergic conductances (Staley et al., 1998). This discrepancy most likely reflects the different developmental stage of the network. GABAA receptors are phosphorylated by different kinases (Poisbeau et al., 1999) and modulated by hormones (Lambert et al., 2003), environmental metabolic products (Pasternack et al., 1996), and drugs (Havers and Luddens, 1998). All these factors could play important roles in gating and/or grading bursting in individual neurons without affecting their participation to the general network burst frequency. This mechanism is likely to play an important role in the spatial selection of bursting neuronal assemblies in vivo. For example, not all CA3 pyramidal neurons burst during SWs (Buzsaki, 1986; Csicsvari et al., 2000): such a selection mechanism could have important consequence for the induction of long-term synaptic plasticity (Buzsaki, 1989). It is important to underscore that our experimental approach coupled with modeling is very different from the more traditional experiments based on unspecific blockade of GABAA receptors in the circuit. Indeed, unspecific blockade of GABAA receptors in a slice changes both burst strength and interburst frequency (Fig. 2) (Korn et al., 1987; Staley et al., 1998; Khazipov et al., 2004). The change in network frequency makes the differences between bursts in the presence and absence of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition extremely difficult to interpret. For example, a change in the frequency of spontaneous events will initiate bursting at a different phase of the burst afterhyperpolarization (Alger and Nicoll, 1980; Chamberlin and Dingledine, 1989) and lead to the recruitment of different cell assemblies (Traub and Miles, 1991). Furthermore, the reduced frequency of spontaneous bursts is likely to interfere with the short-term plasticity (Salin et al., 1996) and glutamate release probability (Staley et al., 1998) of excitatory recurrent collateral connections. In addition, the use of unspecific GABAA receptor antagonists may affect intracellular chloride homeostasis and thus enhance GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition (Lopantsev and Schwartzkroin, 1999, 2001). Similarly, blockade of fast inhibition on interneurons (Hajos and Mody, 1997) may lead to increased firing and consequently augmented GABAB receptor-mediated inhibition (Traub and Miles, 1991; Miles and Wong, 1984; Scanziani, 2000). Finally, as we show here, GABAA receptor blockade results in transient and irregular network hyperexcitability before a new steady state is reached (Fig. 2). This transient period of irregular hyperexcitability may trigger long-term changes of inhibitory or excitatory synaptic transmission (Bains et al., 1999; Chevaleyre and Castillo, 2003). In conclusion, application of GABAA receptor antagonists on the entire slice triggers a cascade of indirect events that makes it impossible to assess the direct role of fast inhibition on pyramidal cell bursting. Here, we also show that the effect of GABAA antagonists on network frequency of synchronous events in the recorded cells requires blockade of receptors in the entire slice. The most parsimonious explanation is that increased interneuron firing results in enhanced presynaptic and/or postsynaptic GABAB-mediated inhibition (Scanziani, 2000). Indeed, the slow kinetics of postsynaptic GABAB receptor-operated conductances (Otis et al., 1993) would be predicted to increase the interburst duration.

Natural pattern of activation of inhibitory conductances during a burst cycle

Network modeling studies have suggested that a burst cycle is always initiated by a single or a few “ancestral” CA3 pyramidal neurons bursting spontaneously (Traub and Miles, 1991). Under this assumption, action potentials in these ancestral cells would result in glutamate release and suprathreshold activation of a fraction of their postsynaptic targets (i.e., pyramidal cells and GABA-releasing interneurons). Spike timing in these first targets would be primarily determined by their specific EPSP-spike coupling properties and, in turn, would then determine the activation of GABAergic and glutamatergic conductances in the next round of postsynaptic neurons, which are disynaptically connected to the initiating cells. EPSP-spike coupling properties are different between pyramidal cells and specific classes of interneurons and depend on their specific intrinsic and synaptic properties (Fricker and Miles, 2001; Maccaferri and Dingledine, 2002). If interneuron firing preceded and outlasted firing in pyramidal cells (Fricker and Miles, 2001; Maccaferri and Dingledine, 2002), then activation of GABAA receptor-mediated conductances would be expected to have a broader duration than excitatory input. However, the progressive recruitment of additional cells of the CA3 circuit would make the interplay between synaptic input and intrinsic properties much more complex and even difficult to predict. Here, we provide the first direct experimental quantification of the natural pattern of activity of fast inhibitory and excitatory conductances during the same burst cycle. The finding that the mean pyramidal cell bIPSC precedes the mean pyramidal cell bEPSC is apparently paradoxical but consistent with the “ancestral pyramidal neuron(s)” hypothesis of Traub and Miles (1991). Our results also clearly show that horizontal stratum oriens cells are powerfully active during network bursting. This broad class of interneurons includes cells with different axonal patterns that target several distinct postsynaptic domains on target pyramidal cells (Maccaferri et al., 2000). Therefore, it is not surprising that fast inhibitory conductances can have a significant impact on burst regulation. For example, besides gating suprathreshold activity, our simulations suggest that the ratio between inhibitory and excitatory burst conductances contributes significantly to setting the appropriate spike timing during a burst cycle (Fig. 9).

Cell type-specific inhibition and regulation of network bursting

A high degree of target cell specificity has been described for a few classes of GABAergic interneurons. Specific classes of axoaxonic and perisomatic targeting cells (Somogyi et al., 1983; Acsady et al., 2000), for example, establish synaptic contacts preferentially on excitatory neurons when compared with interneurons. Nevertheless, interneurons specifically targeting other interneurons have also been described (Freund and Buzsaki, 1996). These classes of interneurons would be predicted to generate a cell type-specific biased GABAergic input. Here, we show that, in addition to intrinsic properties, cell type-specific inhibitory input further contributes to the maintenance of the appropriate spike timing between pyramidal cells and stratum oriens horizontal interneurons. Our experiments demonstrate that a pyramidal cell-specific input is functional during synchronous bursting and that the ratio between the overall GABAA receptor-mediated and fast excitatory inputs is larger in pyramidal cells compared with stratum oriens horizontal interneurons. Recently, Kogo et al. (2004) have shown cell type-specific depression of GABAergic input in stratum oriens horizontal interneurons, mediated by activation of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). Therefore, it is also possible that group III mGluRs might depress fast inhibition in stratum oriens horizontal interneurons during synchronous activity. What interneuron subtype(s) originate(s) the pyramidal cell-specific input? At present, we can only speculate that our observation of a selective flurry of GABAergic input at the beginning of a burst cycle reminds of the observation that axoaxonic cells fire immediately before the initiation of a SW cycle in the CA1 region in vivo (Klausberger et al., 2003). If this was the case, the domain-specific location of this input would be perfectly suited to prevent or delay firing. Our simulations and dynamic-clamp experiments suggest that this type of input could be important to maintain the appropriate spike timing in pyramidal cells, which is an essential variable in the induction of some forms of long-term synaptic plasticity (Bi and Poo, 1998). The occurrence of early spiking during the burst could trigger back-propagating action potentials inducing associative synaptic depression that could lead to the shutdown of the network-driven activity (Bi and Poo, 1998; Bains et al., 1999). Finally, it is interesting to note that the composition of GABAA receptors expressed on the axon initial segment of pyramidal cells is enriched in α2 subunits (Nusser et al., 1996), suggesting the possibility of specific pharmacological modulation. In contrast, the cell type-specific differences in kinetics of excitatory synaptic transmission during the interburst intervals are strongly attenuated during burst events, which are of much longer duration (Fig. 10). This network-state specificity is likely to be important for the maintenance of synchronicity between pyramidal cells and interneurons.

In conclusion, we have unveiled new mechanisms of burst control in the CA3 hippocampus, highlighting a precise role for cell type-specific GABAergic input. This new knowledge could prompt future development of different pharmacological strategies in the treatment of brain conditions associated with burst hyperexcitability and synchronicity, such as epilepsy.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant 5R01MH067561 to G.M.) and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R. Dingledine) during its preliminary phase. We thank Dr. C. McBain (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health) and Drs. M. Bevan, A. Contractor, D. McCrimmon, and M. Martina for constructive criticism of this manuscript. In addition, we thank Dr. R. Dingledine (Emory University, Atlanta, GA) for help and support in pilot experiments leading to this project. We also thank Dr. C. J. Heckman for help in the cross-correlation analysis and Dr. J. Dempster (University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK) for providing us with the Whole-Cell Program analysis package.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Gianmaria Maccaferri, Department of Physiology, Northwestern University Medical School, 303 East Chicago Avenue, Tarry Building, Room 5-707 M211, Chicago, IL 60611. E-mail: g-maccaferri@northwestern.edu.

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/249681-12$15.00/0

References

- Acsady L, Katona I, Martinez-Guijarro FJ, Buzsaki G, Freund TF (2000) Unusual target selectivity of perisomatic inhibitory cells in the hilar region of the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci 20: 6907-6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alger BE, Nicoll RA (1980) Epileptiform burst afterhyperpolarization: calcium-dependent potassium potential in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Science 210: 1122-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aradi I, Santhakumar V, Soltesz I (2004) Impact of perisomatic IPSC populations on pyramidal cell firing rates. J Neurophysiol 91: 2849-2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains JS, Longacher JM, Staley KJ (1999) Reciprocal interactions between CA3 network activity and strength of recurrent collateral synapses. Nat Neurosci 2: 720-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi GQ, Poo MM (1998) Synaptic modifications in culture hippocampal neurons: dependence on spike timing, synaptic strength, and postsynaptic cell type. J Neurosci 18: 10464-10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann JH, Hamill OP, Sakmann B (1987) Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. J Physiol (Lond) 385: 243-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl EH, Halasy K, Somogyi P (1994) Diverse source of hippocampal unitary inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and the number of synaptic release sites. Nature 368: 823-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G (1986) Hippocampal sharp waves: their origin and significance. Brain Res 398: 242-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G (1989) Two-stage model of memory trace formation: a role for “noisy” brain states. Neuroscience 31: 551-570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsaki G, Leung LM, Vanderwolf CH (1983) Cellular bases of hippocampal EGG in behaving rat. Brain Res 287: 139-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Dingledine R (1989) Control of epileptiform burst rate by CA3 hippocampal cell afterhyperpolarizations in vitro. Brain Res 492: 337-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevaleyre V, Castillo PE (2003) Heterosynaptic LTD of hippocampal GABAergic synapses: a novel role of endocannabinoids in regulating excitability. Neuron 38: 461-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csicsvari J, Hirase H, Mamiya A, Buzsaki G (2000) Ensemble patterns of hippocampal CA3-CA1 neurons during sharp wave-associated population events. Neuron 28: 585-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhala VI, Staley KJ (2003) Excitatory actions of endogenously released GABA contribute to initiation of ictal epileptiform activity in the developing hippocampus. J Neurosci 23: 1840-1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund T, Buzsaki G (1996) Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus 6: 347-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker D, Miles R (2001) EPSP amplification and the precision of spike timing in the hippocampus. Neuron 28: 559-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos N, Mody I (1997) Synaptic communication among hippocampal interneurons: properties of spontaneous IPSCs in morphologically identified cells. J Neurosci 17: 8427-8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havers W, Luddens H (1998) The diversity of GABAA receptors. Pharmacological and electrophysiological properties of GABAA channel subtypes. Mol Neurobiol 18: 35-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaulme M, Chambon JP, Leyris R, Molimard JC, Wermuth CG, Biziere K (1986) Biochemical characterization of the interaction of three pyridazinyl-GABA derivatives with the GABAA receptor site. Brain Res 384: 224-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestrin S, Nicoll RA, Perkel DJ, Sah P (1990) Analysis of excitatory synaptic action in pyramidal cells using whole-cell recording from rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol (Lond) 422: 203-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines ML, Carnevale NT (1997) The NEURON simulation environment. Neural Comput 9: 1179-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamondi A, Acsady L, Buzsaki G (1998) Dendritic spikes are enhanced by cooperative network activity in the intact hippocampus. J Neurosci 18: 3919-3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R, Khalilov RT, Morozova E, Ben-Ari Y, Holmes GL (2004) Developmental changes in GABAergic actions and seizure susceptibility in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci 19: 590-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Marton LF, Roberts JD, Cobden PM, Buzsaki G, Somogyi P (2003) Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature 421: 844-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogo N, Dalezios Y, Capogna M, Ferraguti F, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P (2004) Depression of GABAergic input to identified hippocampal neurons by group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 19: 2727-2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn SJ, Giacchino JL, Chamberlin NL, Dingledine R (1987) Epileptiform burst activity induced by potassium in the hippocampus and its regulation by GABA-mediated inhibition. J Neurophysiol 57: 325-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Peden DR, Vardy AW, Peters JA (2003) Neurosteroid modulation of GABAA receptors. Prog Neurobiol 71: 67-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XG, Somogyi P, Ylinen A, Buzsaki G (1994) The hippocampal CA3 network: an in vivo intracellular labeling study. J Comp Neurol 339: 181-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopantsev V, Schwartzkroin PA (1999) GABAA-dependent chloride influx modulates GABAB-mediated IPSPs in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol 82: 1218-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopantsev V, Schwartzkroin PA (2001) GABAA-dependent chloride influx modulates reversal potential of GABAB-mediated IPSPs in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol 85: 2381-2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Dingledine R (2002) Control of feedforward dendritic inhibition by NMDA receptor-dependent spike timing in hippocampal interneurons. J Neurosci 22: 5462-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccaferri G, Roberts JD, Szucs P, Cottingham CA, Somogyi P (2000) Cell surface domain specific postsynaptic currents evoked by identified GABAergic neurons in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 524: 91-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacVicar BA, Dudek FE (1982) Local circuit interactions in rat hippocampus: interactions between pyramidal cells. Brain Res 242: 341-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Ajmone-Marsan C (1964) Cortical cellular phenomena in experimental epilepsy: interictal manifestations. Exp Neurol 9: 286-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ (1995) Hippocampal inhibitory neuron activity in the elevated potassium model of epilepsy. J Neurophysiol 73: 2853-2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBain CJ, Traynelis SF, Dingledine R (1993) High potassium-induced synchronous bursts and electrographic seizures. In: Epilepsy: models, mechanisms and concepts (Schwartzkroin PA, ed), pp 437-461. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP.

- Migliore M, Cook EP, Jaffe DB, Turner DA, Johnston D (1995) Computer simulations of morphologically reconstructed CA3 hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol 73: 1157-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Wong RKS (1983) Single neurons can initiate synchronized population discharges in the hippocampus. Nature 306: 371-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Wong RKS (1984) Unitary inhibitory synaptic potentials in the guina-pig hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 356: 97-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusser Z, Sieghart W, Benke D, Fritschy JM, Somogyi P (1996) Differential synaptic localization of two major gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor alpha subuinits on hippocampal pyramidal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 11939-11944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis TS, De Konick Y, Mody I (1993) Characterization of synaptically elicited GABAB responses using patch-clamp recordings in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol (Lond) 463: 391-407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternack M, Smirnov S, Kaila K (1996) Proton modulation of functionally distinct GABAA receptors in acutely isolated pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 35: 1279-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisbeau P, Cheney MC, Browning MD, Mody I (1999) Modulation of synaptic GABAA receptor function by PKA and PKC in adult hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci 19: 674-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson HP, Kawai N (2000) Injection of digitally synthesized synaptic conductance transients to measure the integrative properties of neurons. J Neurosci Methods 49: 157-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki PA, Lebeda FJ, Johnston D (1985) Epileptiform activity induced by changes in extracellular potassium in hippocampus. J Neurophysiol 54: 1363-1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Hestrin S, Nicoll RA (1990) Properties of excitatory postsynaptic currents recorded in vitro from rat hippocampal interneurons. J Physiol (Lond) 430: 605-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin PA, Scanziani M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA (1996) Distinct short-term plasticity at two excitatory synapses in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 13304-13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanziani M (2000) GABA spillover activates postsynaptic GABA(B) receptors to control rhythmic hippocampal activity. Neuron 25: 673-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzkroin PA, Haglund MM (1986) Spontaneous rhythmic synchronous activity in epileptic human and normal monkey temporal lobe. Epilepsia 27: 523-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Nunzi MG, Gorio A, Smith AD (1983) A new type of specific interneuron in the monkey hippocampus forming synapses exclusevely with the axon initial segments of pyramidal cells. Brain Res 259: 137-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley KJ, Longacher M, Bains JS, Yee A (1998) Presynaptic modulation of CA3 network activity. Nat Neurosci 1: 201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki SS, Smith GK (1985) Single-cell activity and synchronous bursting in the rat hippocampus during waking behavior and sleep. Exp Neurol 89: 71-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki SS, Smith GK (1988) Spontaneous EEG spikes in the normal hippocampus. II. Relations to synchronous burst discharges. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 69: 532-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traub RD, Miles R (1991) Neuronal networks of the hippocampus. New York: Cambridge UP.

- Traub RD, Wong RK, Miles R, Michelson H (1991) A model of a CA3 hippocampal pyramidal neuron incorporating coltage-clamp data on intrinsic conductances. J Neurophysiol 66: 635-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Dingledine R (1988) Potassium-induced spontaneous electrographic seizures in the rat hippocampal slice. J Neurophysiol 59: 259-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WA, Bragdon A (1993) Brain slice models for the study of seizures and interictal spikes. In: Epilepsy: models, mechanisms and concepts (Schwartzkroin PA, ed), pp 371-387. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP.

- Wong RKS, Prince DA (1981) Afterpotential generation in hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol 45: 86-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]