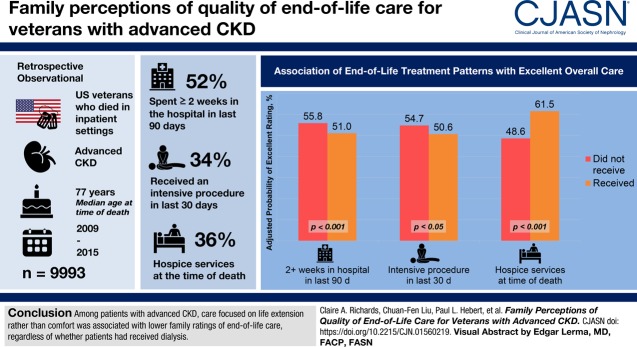

Visual Abstract

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, dialysis, palliative care, patient-centered care, quality of life, kidney failure, intensive treatment, end-of-life care, bereaved family, humans, hospices, retrospective studies, veterans, life expectancy, logistic models, terminal care, hospice care, referral and consultation, death, intensive care units, chronic renal insufficiency

Abstract

Background and objectives

Little is known about the quality of end-of-life care for patients with advanced CKD. We describe the relationship between patterns of end-of-life care and dialysis treatment with family-reported quality of end-of-life care in this population.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We designed a retrospective observational study among a national cohort of 9993 veterans with advanced CKD who died in Department of Veterans Affairs facilities between 2009 and 2015. We used logistic regression to evaluate associations between patterns of end-of-life care and receipt of dialysis (no dialysis, acute dialysis, maintenance dialysis) with family-reported quality of end-of-life care.

Results

Overall, 52% of cohort members spent ≥2 weeks in the hospital in the last 90 days of life, 34% received an intensive procedure, and 47% were admitted to the intensive care unit, in the last 30 days, 31% died in the intensive care unit, 38% received a palliative care consultation in the last 90 days, and 36% were receiving hospice services at the time of death. Most (55%) did not receive dialysis, 12% received acute dialysis, and 34% received maintenance dialysis. Patients treated with acute or maintenance dialysis had more intensive patterns of end-of-life care than those not treated with dialysis. After adjustment for patient and facility characteristics, receipt of maintenance (but not acute) dialysis and more intensive patterns of end-of-life care were associated with lower overall family ratings of end-of-life care, whereas receipt of palliative care and hospice services were associated with higher overall ratings. The association between maintenance dialysis and overall quality of care was attenuated after additional adjustment for end-of-life treatment patterns.

Conclusions

Among patients with advanced CKD, care focused on life extension rather than comfort was associated with lower family ratings of end-of-life care regardless of whether patients had received dialysis.

Introduction

Despite having a high symptom burden and limited life expectancy (1–3), patients with advanced CKD spend more time in the hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) during the final months of life and are more likely to receive high intensity interventions intended to prolong life (e.g., mechanical ventilation) than patients with some other serious illnesses (3–5). Conversely, they are less likely to receive palliative and hospice care services (5,6). Patients with advanced CKD who are treated with dialysis also receive more intensive patterns of end-of-life care than those who forego dialysis (6).

These potentially burdensome patterns of care among patients with advanced CKD have raised concerns about the quality of end-of-life care for members of this population. Studies in more broadly defined populations have demonstrated that more intensive patterns of end-of-life care focused primarily on life extension rather than comfort are associated with lower quality of end-of-life care (7–10). However, most prior studies of end-of-life care among patients advanced CKD have focused on symptom burden rather than on patients’ and/or family members’ satisfaction or experiences with end-of-life care (3,11,12).

Wachterman et al. (5) compared family ratings of end-of-life care among veterans with a range of different advanced chronic conditions and found that these were less favorable for patients with ESKD than for those with cancer or dementia. However, these authors did not examine the relationship between patterns of end-of-life care and family ratings of care among patients with ESKD. Nor did they compare quality of end-of-life care among subgroups within this population, such as those who were treated versus not treated with dialysis or those who received acute versus maintenance dialysis. Such information may help to generate hypotheses about what factors drive quality of end-of-life care in patients with advanced CKD and to identify opportunities for improvement.

We designed a study to describe the relationship between patterns of end-of-life care and exposure to dialysis treatment (no dialysis, acute dialysis, and maintenance dialysis) with family-rated quality of end-of-life care among a national cohort of patients with advanced CKD.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Study Population

We used demographic and laboratory data from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to assemble a national cohort of veterans with advanced CKD (defined as having an eGFR <20 ml/min per 1.73 m2, calculated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation on two separate occasions, at least 90 days apart) between calendar years 2000 and 2014 (Figure 1) (13). We obtained linked data for cohort members from the VA’s Veteran Experience Center, the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), VA Inpatient, Outpatient, and Fee Basis files, and Medicare Institutional and Carrier files. Since October 1, 2009, the Veteran Experience Center has administered the Bereaved Family Survey (BFS) to the next of kin of all eligible patients who die in a VA inpatient facility (including intensive care, acute care, dedicated hospice and palliative care units, and nursing homes) within 6–10 weeks after death (14–16).

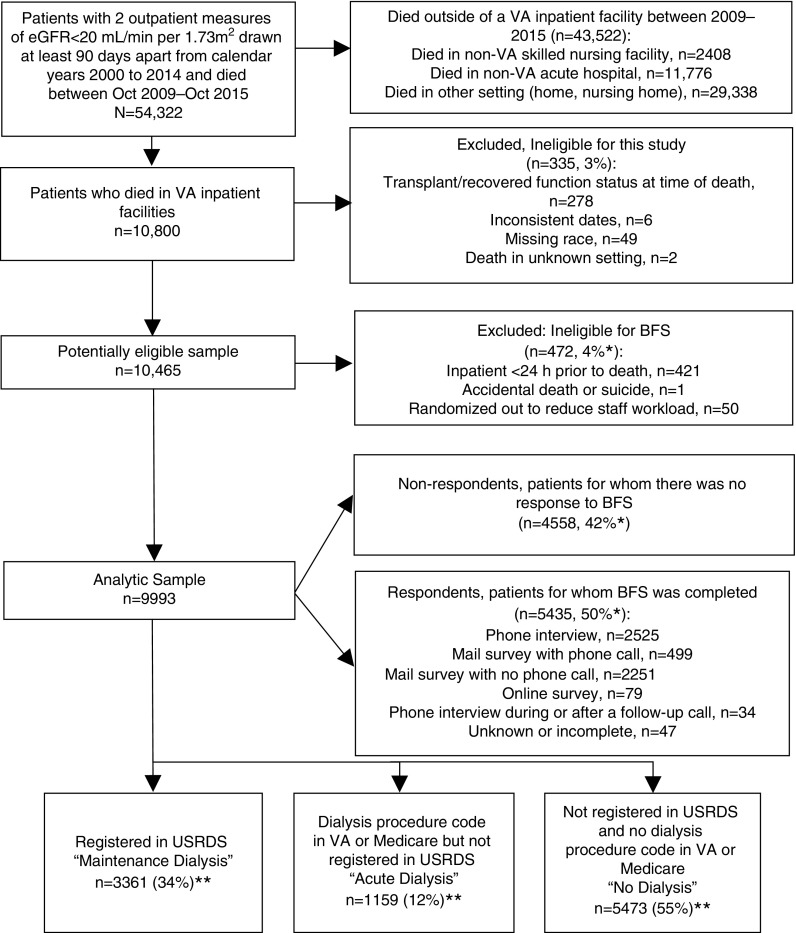

Figure 1.

Cohort derivation. *Denominator includes patients who died in VA inpatient settings during the study period (n=10,800). **Percentages do not sum to 100% due to rounding.

We excluded veterans if they were missing information on race or setting of death, had records with date inconsistencies (e.g., dialysis treatment recorded after death), and if they appeared in the USRDS registry but had recovered kidney function or had a functioning kidney transplant at the time of death. We did not exclude patients who had previously received dialysis for AKI. The cohort comprised 9993 veteran who died in VA facilities between fiscal years 2010–2014 and whose family members were invited to complete the BFS. Family members of 5435 (54%) cohort members completed the survey (Figure 1). The VA Central Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Exposure

End-of-Life Treatment Patterns

The following measures of high-intensity treatment directed at life extension were selected a priori: two or more weeks spent in an acute hospital within 90 days of death, ICU admission within 30 days, receipt of at least one intensive procedure within 30 days (intubation/mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, feeding tube placement, enteral nutrition, or tracheostomy) (17), and death in the ICU (Supplemental Appendix 1). The following process measures for palliative care were also selected a priori: palliative care consultation within 90 days of death and receipt of hospice services at the time of death. All of the measures selected have been shown to be associated with quality of life or quality of end-of-life care in other populations (5,7,9,10,18,19).

Dialysis Status

Patients were grouped as follows based on their exposure to dialysis: (1) maintenance dialysis: patients enrolled in the USRDS registry for whom the last treatment modality recorded in the USRDS Treatment History File was hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or unknown (Figure 1); (2) acute dialysis: patients who were not enrolled in the USRDS registry but had least one diagnostic or procedure code for dialysis (Supplemental Appendix 1) under VA or Medicare in the year before death; (20) (3) no dialysis: patients who were not enrolled in the USRDS registry and who did not have a procedure or diagnostic code for dialysis in the year before death (6).

Outcome

Family-Rated Quality of End-of-Life Care

The BFS is a National Quality Forum–endorsed survey for assessing bereaved family members’ perceptions of patients’ quality of care during the last month of life (7,15,16,18,21). Our primary outcome was the BFS global rating of overall quality of end-of-life care categorized as “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” We also included scores on ten individual BFS items pertaining to communication, support, and pain management (16). To be consistent with earlier studies, responses for all individual items except for pain were categorized as the most favorable versus all other responses (5,14,15). Frequency of discomfort from pain was dichotomized as “never” or “sometimes” versus all other responses.

Covariates

All analyses were adjusted for patient- and facility-level characteristics that we hypothesized might be associated with end-of-life treatment patterns and family-rated quality of end-of-life care (14,15). These included sex, age at death, race, relationship of the next of kin (spouse, sibling, child, or other), all individual comorbidities other than kidney disease that are included in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (revised for administrative data by Quan et al. [22] and modified to include an expanded list of codes for dementia [23] and peripheral vascular disease [1]; Supplemental Appendix 1), census region, and facility complexity.

Analysis

We used logistic regression to examine the relationship between end-of-life treatment patterns and dialysis treatment status with scores on the BFS global item. For each variable, we fit an unadjusted model and a model adjusted for the aforementioned covariates. We used the same approach to evaluate the relationship between dialysis treatment status and scores on individual BFS items.

To evaluate whether differences in end-of-life treatment patterns might confound observed differences in family-rated quality of end-of-life care among patients with differing exposure to dialysis, we also evaluated this relationship after additional adjustment for end-of-life treatment patterns. Finally, to address the possibility of survivor selection bias due to a mismatch between dates of cohort entry and availability of BFS data, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients who entered the cohort after September 2009.

In all models, we used robust estimates of variance to account for facility-level clustering (n=123). We calculated the predicted probabilities and average marginal effects for predictors of interest using the distribution of covariates in the sample. Average marginal effects are presented as risk differences. For multivariable models involving survey responses, we adjusted for survey and item nonresponse by weighting and multiple imputation (Supplemental Appendix 2) (24–26). We used SAS version 9.4 software (27) to construct the dataset, STATA version 15 (28) and R 3.5.1 (29) to conduct statistical analyses, and MIMRGNS to calculate the average marginal effects for multiply imputed data in STATA (30).

Results

Among the 9993 cohort members, the mean (SD) age at the time of death was 76 (11) years (interquartile range [IQR], 66–85 years), 25% were black, and 97% were men. The documented next-of-kin was a spouse/partner (40%) or a child (35%) in most instances (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of cohort members

| Variables | No Dialysis | Acute Dialysis | Maintenance Dialysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (%)a | 5473 (55) | 1159 (12) | 3361 (34) |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 79 (11) | 72 (10) | 71 (10) |

| Age group, % | |||

| <65 yr | 12 | 25 | 31 |

| 65–74 yr | 18 | 31 | 34 |

| 75–84 yr | 32 | 32 | 24 |

| 85+ yr | 38 | 13 | 11 |

| Male sex, % | 97 | 98 | 99 |

| Race, % | |||

| Black | 18 | 25 | 37 |

| White | 80 | 73 | 60 |

| Other | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Next of kin, %a | |||

| Spouse/partner | 37 | 42 | 45 |

| Child | 39 | 37 | 29 |

| Sibling | 10 | 10 | 13 |

| Other | 15 | 12 | 13 |

| Comorbidities, % | |||

| Diabetes mellitusb | 56 | 69 | 75 |

| Congestive heart failure | 63 | 72 | 70 |

| Myocardial infarction | 24 | 30 | 32 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 55 | 57 | 53 |

| Liver diseaseb | 14 | 21 | 26 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 31 | 29 | 35 |

| Peripheral vascular diseasec | 35 | 40 | 56 |

| Dementiac | 26 | 12 | 17 |

| Cancerb | 41 | 30 | 29 |

| Region, %a | |||

| New England | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Mid Atlantic | 16 | 14 | 13 |

| East North Central | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| West North Central | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| South Atlantic | 23 | 22 | 25 |

| East South Central | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| West South Central | 10 | 14 | 12 |

| Mountain | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Pacific | 11 | 14 | 13 |

| Facility complexity, % | |||

| High (level 1a, 1b, and 1c) | 83 | 94 | 92 |

| Low (level 2 and 3) | 17 | 6 | 8 |

Does not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Includes both Charlson Comorbidity Index diagnostic categories of mild and severe.

Diagnostic categories expanded (Supplemental Appendix 1).

Patterns of End-of-Life Care

Overall, 54% of cohort members spent two or more weeks in the hospital in the last 90 days of life, 34% received an intensive procedure in the last 30 days, 47% were admitted to the ICU in the last 30 days, 36% were receiving hospice services at the time of death, and 38% received a palliative care consultation in the last 90 days (Supplemental Table 1). Overall, 31% died in the ICU, 27% on acute care wards, 16% in a nursing home, and 26% in a dedicated inpatient hospice or palliative care unit.

Most (55%) cohort members had not received dialysis, 12% had received acute, and 34% had received maintenance dialysis. Among the maintenance dialysis group, most (96%) had received hemodialysis. The median time from cohort entry to death was 9.2 months (IQR, 0.9–32.6) for those not treated with dialysis, 7.7 months (IQR, 1.2–28.8) for those treated with acute dialysis, and 51.7 months (IQR, 24.9–86.5) for those treated with maintenance dialysis. For the acute dialysis group, the median time between the first procedure code for dialysis during the last year of life and the date of death was 32 days (IQR, 13–122). For the maintenance dialysis group, the median time between onset of ESKD and death was 37.9 months (IQR, 15.6–72.5).

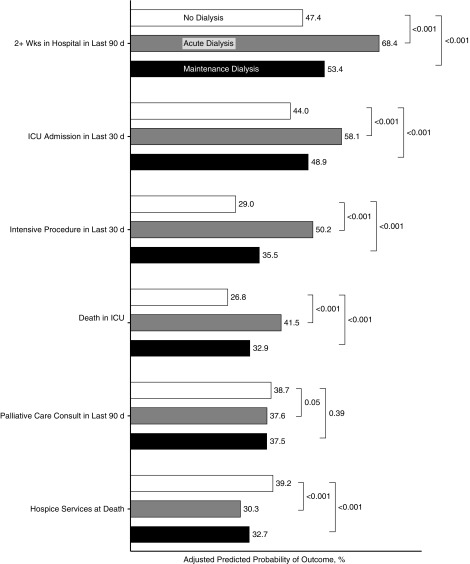

In analyses adjusted for patient- and facility-level characteristics (Figure 2, Supplemental Table 2), patients treated with acute or maintenance dialysis were more likely than the reference group not treated with dialysis to have spent two or more weeks in the hospital during the last 90 days of life (predicted probability, 68.4% [acute dialysis] versus 53.4% [maintenance dialysis] versus 47.4% [no dialysis]; P<0.001). They were also more likely to have been admitted to the ICU in the last 30 days (58.1% versus 48.9% versus 44.0%; P<0.001), to have received an intensive procedure in the last 30 days (50.2% versus 35.5% versus 29.0%; P<0.001), and to have died in the ICU (41.5% versus 32.9% versus 26.8%; P<0.001). Patients treated with acute or maintenance dialysis were less likely than those not treated with dialysis to have received hospice services (30.3% versus 32.7% versus 39.2%; P<0.001), but there were no differences between groups in receipt of a palliative care consultation in the last 90 days (acute dialysis 37.5% versus 38.7%; P=0.50; maintenance dialysis 37.5% versus 38.7%; P=0.39).

Figure 2.

Association of dialysis treatment status with end-of-life treatment patterns. Parameters are predicted probabilities; reference group for acute and maintenance dialysis is no dialysis and reference group for end-of-life treatment variables is no receipt; model adjusted for race, age, sex, next of kin, region, facility complexity, year of death, and individual comorbidities, standard errors adjusted for facility-level clustering. n=9993. ICU, intensive care unit.

Family-Rated Quality of Care

Of the 5435 (54%) cohort members whose family members responded to the BFS (Supplemental Table 3), 55% rated their overall quality of care as excellent (Supplemental Table 4). For individual items pertaining to communication and support, the proportions whose family members provided favorable ratings ranged from 59% (providers “always” provided spiritual support) to 80% (staff were “always” kind, caring, and respectful) across measures. Approximately one half of respondents reported that the patient was “never” or “sometimes” uncomfortable from pain.

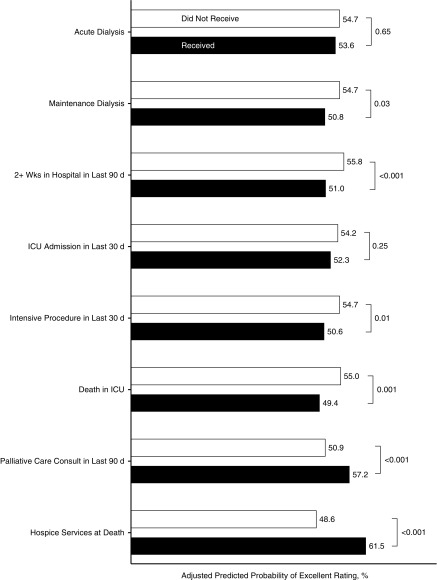

In analyses adjusted for patient- and facility-level characteristics (Table 2, Figure 3), family members of patients who spent two or more weeks in the hospital during the last 90 days of life were less likely to rate the overall quality of care as excellent than those who did not (predicted probability, 51.0% versus 55.8%; P<0.001). This was also true for patients who received an intensive procedure in the last 30 days (50.6% versus 54.7%; P=0.01) and for those who died in the ICU (49.4% versus 55.0%; P=0.001). Conversely, family-rated overall quality of care for patients who received a palliative care consult within the last 90 days of life or were receiving hospice services at the time of death was higher than for those who did not (57.2% versus 50.9%; P<0.001; 61.5% versus 48.6%; P<0.001, respectively). Admission to the ICU in the last 30 days of life was not significantly associated with overall quality of care (52.3% versus 54.1%; P=0.25).

Table 2.

Association of end-of-life treatment and dialysis treatment status with excellent overall care

| Treatmenta | Unadjusted Results (n=5344)b | Adjusted Results (n=5435)bc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value | % | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Dialysis treatment status | ||||||

| No dialysis | 58.8 | Reference | 54.7 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 52.1 | −6.7 (−10.9 to −2.5) | 0.002 | 53.6 | −1.1 (−6.0 to 3.7) | 0.65 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 48.2 | −10.6 (−13.5 to −7.6) | <0.001 | 50.8 | −3.9 (−7.5 to −0.4) | 0.03 |

| High-intensity treatment | ||||||

| 2+wks in hospital in last 90 d | ||||||

| No | 59.1 | Reference | 55.8 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 50.3 | −8.7 (−11.2 to -6.2) | <0.001 | 51.0 | −4.9 (−7.6 to −2.1) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission in last 30 d | ||||||

| No | 57.4 | Reference | 54.2 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 51.6 | −8.9 (−8.7 to −2.7) | <0.001 | 52.3 | −1.9 (−5.1 to 1.3) | 0.25 |

| Intensive procedure in last 30 d | ||||||

| No | 57.6 | Reference | 54.7 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 48.5 | −9.1 (−12.2 to −6.0) | <0.001 | 50.6 | −4.1 (−7.3 to −0.9) | 0.01 |

| Death in intensive care unit | ||||||

| No | 57.6 | Reference | 55.0 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 47.5 | −10.2 (−13.5 to −6.8) | <0.001 | 49.4 | −5.6 (−9.1 to −2.2) | 0.001 |

| Palliative and hospice care | ||||||

| Palliative care consultation in last 90 d | ||||||

| No | 52.7 | Reference | 50.9 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 58.3 | 5.6 (3.0 to 8.3) | <0.001 | 57.2 | 6.4 (3.7 to 9.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospice services at time of death | ||||||

| No | 48.9 | Reference | 48.6 | Reference | ||

| Yes | 63.9 | 15.1 (11.9 to 18.2) | <0.001 | 61.5 | 12.8 (9.4 to 16.3) | <0.001 |

Logistic regression with no dialysis as reference group for acute and maintenance dialysis and no receipt as reference group for end-of-life treatment variables, standard errors adjusted for facility-level clustering; presented are the predicted probabilities over the distribution of covariates in the respondent sample; 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and P values are for differences in the predicted probabilities.

Dichotomized as “excellent” versus all other responses.

Denominators differ for unadjusted and adjusted models because missing items were imputed in adjusted models only (Supplemental Appendix 2, Supplemental Table 4).

Model adjusted for race, age, sex, next of kin, region, facility complexity, year of death, and individual comorbidities, and weighted for unit nonresponse.

Figure 3.

Association of dialysis and end-of-life treatment with excellent overall care. Parameters are predicted probabilities of excellent rating versus all others; reference group for acute and maintenance dialysis is no dialysis and reference group for end-of-life treatment variables is no receipt; model adjusted for race, age, sex, next of kin, region, facility complexity, year of death, individual comorbidities and Quan quantile, weighted for survey nonresponse and missing items imputed, standard errors adjusted for facility-level clustering. n=5435. ICU, Intensive care unit.

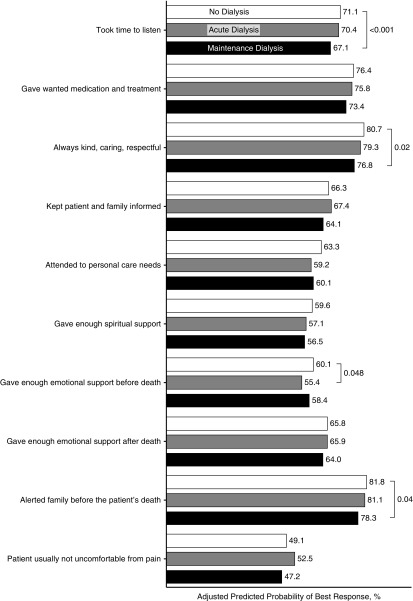

Family-rated overall quality of care for patients who had received maintenance dialysis was lower than for patients not treated with dialysis (50.8% versus 54.7%; P=0.03), whereas there was no difference between those who had received acute versus no dialysis (53.6% versus 54.7%; P=0.65). Responses were less favorable for those who had received maintenance versus no dialysis for the following individual BFS items: providers always took time to listen (67.1% versus 71.1%; P=0.01); were kind, caring, and respectful (76.8% versus 80.7%; P=0.02); and alerted family to the patient’s impending death (78.3% versus 81.8%; P=0.04) (Figure 4, Table 3). Only one item pertaining to emotional support before death differed for those who had received acute versus no dialysis (55.4% versus 60.1%; P=0.048).

Figure 4.

Association of dialysis treatment status with most favorable response on individual bereaved family survey items. Presented are predicted probabilities of giving most favorable response versus all others; reference group is no dialysis; model is adjusted for race, age, sex, next of kin, region, facility complexity, year of death, individual comorbidities, weighted for survey nonresponse and missing items imputed; standard errors adjusted for facility-level clustering. n=5435.

Table 3.

Association of dialysis treatment status with most favorable response on individual Bereaved Family Survey items

| Bereaved Family Survey Itema Dialysis Treatment Status | Unadjustedb | Adjusted (n=5435)c | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value | % | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Always took time to listen | ||||||

| No dialysis | 73.7 | Reference | 71.1 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 69.3 | −4.4 (−8.4 to −0.5) | 0.05 | 70.4 | −0.7 (−4.5 to 3.1) | 0.72 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 66.4 | −7.3 (−10.2 to −4.5) | <0.001 | 67.1 | −4.0 (−7.2 to −0.8) | 0.01 |

| Always gave wanted medication and treatment | ||||||

| No dialysis | 79.3 | Reference | 76.4 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 74.7 | −4.6 (−8.3 to −1.0) | 0.05 | 75.8 | −0.7 (−4.4 to 3.1) | 0.73 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 72.8 | −6.6 (−9.1 to −4.1) | <0.001 | 73.4 | −3.0 (−6.1 to 0.0) | 0.05 |

| Always kind, caring, and respectful | ||||||

| No dialysis | 83.1 | Reference | 80.7 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 78.6 | −4.6 (−8.5 to −0.7) | <0.05 | 79.3 | −1.4 (−5.6 to 2.9) | 0.52 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 76.0 | −7.2 (−9.9 to −4.4) | <0.001 | 76.8 | −3.9 (−7.2 to −0.6) | 0.02 |

| Always informed patient and family | ||||||

| No dialysis | 69.1 | Reference | 66.3 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 65.6 | −3.4 (−7.7 to 0.8) | 0.11 | 67.4 | 1.1 (−3.2 to 5.3) | 0.63 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 63.0 | −6.0 (−9.0 to −3.1) | <0.001 | 64.1 | −2.2 (−5.6 to 1.1) | 0.19 |

| Always attended to personal care needs | ||||||

| No dialysis | 66.3 | Reference | 63.3 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 59.8 | −6.5 (−11.7 to −1.2) | 0.02 | 59.2 | −4.1 (−9.5 to 1.2) | 0.13 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 58.4 | −7.9 (−11.6 to −4.2) | <0.001 | 60.1 | −3.2 (−6.8 to 0.4) | 0.08 |

| Always gave enough spiritual support | ||||||

| No dialysis | 61.9 | Reference | 59.6 | |||

| Acute dialysis | 55.5 | −6.3 (−11.1 to −1.5) | 0.01 | 57.1 | −2.5 (−8.0 to 3.0) | 0.37 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 55.2 | −6.6 (−9.6 to −3.6) | <0.001 | 56.5 | −3.1 (−6.6 to 0.4) | 0.08 |

| Always gave enough emotional support before death | ||||||

| No dialysis | 63.7 | Reference | 60.1 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 54.0 | −9.8 (−14.3 to −5.3) | <0.001 | 55.4 | −4.7 (−9.3 to −0.0) | <0.05 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 56.4 | −7.3 (−10.4 to −4.2) | <0.001 | 58.4 | −1.7 (−5.3 to 2.0) | 0.37 |

| Always gave enough emotional support after death | ||||||

| No dialysis | 68.1 | Reference | 65.8 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 64.1 | −4.0 (−8.3 to 0.3) | 0.07 | 65.9 | 0.1 (−4.9 to 5.1) | 0.97 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 62.6 | −5.5 (−8.6 to −2.4) | <0.001 | 64.0 | −1.8 (−5.6 to 2.1) | 0.37 |

| Alerted family before the patient’s death | ||||||

| No dialysis | 81.8 | Reference | 81.8 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 81.1 | −0.7 (−4.8 to 3.4) | 0.74 | 81.1 | −0.7 (−5.0 to 3.7) | 0.77 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 78.4 | −3.3 (−6.3 to −0.4) | 0.03 | 78.3 | −3.5 (−6.8 to −0.2) | 0.04 |

| Patient usually not uncomfortable from paind | ||||||

| No dialysis | 52.2 | Reference | 49.1 | Reference | ||

| Acute dialysis | 51.1 | −1.1 (−5.8 to 3.5) | 0.64 | 52.5 | 3.4 (−1.7 to 8.5) | 0.19 |

| Maintenance dialysis | 44.9 | −7.2 (−10.1 to −4.3) | <0.001 | 47.2 | −1.9 (−5.5 to 1.7) | 0.30 |

Logistic regression with no dialysis group as the reference, confidence intervals adjusted for facility-level clustering; presented are the predicted probabilities over the distribution of covariates in the respondent sample; 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and P values are for differences in the predicted probabilities.

Dichotomized as most favorable response versus all other responses.

Denominators for unadjusted models vary due to missing items (Supplemental Appendix 2, Supplemental Table 4).

Missing items imputed, model adjusted for race, age, sex, next of kin, region, facility complexity, year of death, individual comorbidities, and weighted for unit nonresponse.

Pain was dichotomized as “never” or “sometimes” versus “always” or “usually.”

After additional adjustment for treatment patterns (Supplemental Table 5), differences in ratings of overall quality of care between patients on maintenance dialysis versus no dialysis were attenuated and no longer statistically significant (51.1% versus 54.3%; P=0.07). However, families of patients treated with maintenance dialysis were still less likely to report that they were alerted to the patient’s impending death (78.4% versus 82.0%; P=0.03) and that providers were kind, caring, and respectful (77.1% versus 80.3%; P=0.048), although these differences were attenuated. After adjusting for treatment patterns, no items were significantly different for patients treated with acute versus no dialysis.

Results were similar when analyses were restricted to patients who entered the cohort after September 2009, although 95% confidence intervals around point estimates were substantially wider (Supplemental Tables 6 and 7).

Discussion

Consistent with previous reports among United States veterans and Medicare beneficiaries with ESKD (4,5,31), members of this national cohort of patients with advanced CKD who died in VA inpatient settings received intensive patterns of end-of-life care that appeared to be primarily directed at life extension. Patients with more intensive patterns of care had lower family ratings of overall quality of care, whereas those who received palliative care and hospice services had higher ratings, with the strongest effect noted for receipt of hospice services. Patients treated with maintenance dialysis had lower overall family ratings of end-of-life care than those not treated with dialysis, but these differences were largely attenuated after additional adjustment for their more intensive patterns of end-of-life care. These findings suggest that intensive patterns of end-of-life care directed at life extension rather than comfort among patients with advanced CKD may reflect lower quality of end-of-life care from the perspective of bereaved family members (6,31–33).

The inverse association between care directed at life extension and family ratings of care observed here highlights a potential disconnect between what we know about patients’ expressed preferences for care and the care that many patients with advanced CKD ultimately receive toward the end of life. In contrast with the intensive patterns of end-of-life care described here and elsewhere, when asked about the kind of care they would want to receive if they were seriously ill or dying, many patients with advanced CKD indicate that they would prefer a focus on comfort and relief of suffering rather than life prolongation (34–36). Only a minority of these patients report wanting to live as long as possible, even if this might mean more pain and discomfort (34–37). Although apparent discrepancies between patients’ stated preferences and the kind of care they receive at the end of life may reflect a lack of familiarity with available treatment options and changing preferences over time (38), they likely also suggest that there are opportunities to better align care with patients’ values and goals. Available evidence suggests that patients with advanced CKD often have uncertain and/or unrealistic expectations about the future (35,39), may not be aware of conservative and comfort-oriented treatment options (34,35,37,40), and may not share the same priorities for care as the clinicians caring for them (41,42). Building communication skills among nephrology providers and offering opportunities for patients and their families to discuss their goals and values iteratively throughout the course of illness may help to address some of these deficiencies and help to promote high-quality care at the end of life for members of this population (43).

We are not aware of prior studies that have described quality of end-of-life care for patients with advanced CKD as a function of whether they were treated with dialysis, and specifically among patients who received acute versus long-term dialysis. Interestingly, members of our cohort treated with acute dialysis received more intensive patterns of end-of-life care than any other group. Nonetheless, adjusted family-rated quality of end-of-life care for cohort members who received acute dialysis was no different than for those not treated with dialysis, perhaps suggesting that our analyses do not capture all factors that shape the quality of end-of-life care in this population. In particular, the much shorter short time between dialysis initiation and death among patients who received acute versus maintenance dialysis suggests that there were probably marked differences in the clinical context of care for these two groups that might have shaped experiences of end-of-life care. Factors not captured in our analyses that might influence the quality of end-of-life care include whether dialysis or other intensive treatments were withdrawn before death (44), the extent to which care was concordant with patients’ goals and values (45), and patients’ socioeconomic and functional status. Thus, although high-intensity treatments were generally associated with lower family-rated quality of end-of-life care among cohort members, our findings also argue against relying on end-of-life treatment patterns ascertained from administrative data alone as a proxy for quality of end-of-life care (46).

Our results must be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, some may question the clinical significance of a four to six-point difference in the percentage of family members reporting excellent overall ratings of quality of care for most measures. However, the range of values for BFS responses reported in the literature for national subgroup comparisons is relatively narrow (46%–69.5%) (7,15). Further, even relatively small differences in satisfaction scores can translate into meaningful differences in patient choices and behaviors (47–49). Second, this is an observational study that is hypothesis-generating but cannot support causal inferences. Third, our findings may not be generalizable to patients with advanced CKD not included in this study, including non-veterans and veterans who died at home or in a non-VA facility (Supplemental Table 8) (32). Because we included only patients who died in a VA facility, patterns of end-of-life care were likely more intensive than for the wider population of veterans with advanced CKD. Fourth, there are inherent limitations to measuring the quality of end-of-life care on the basis of the reports of bereaved family members, including the potential for recall bias and the possibility that these may not capture patients’ own experiences (50). Fifth, the mortality follow-back approach used here is subject to bias because it fails to account for the uncertainty about whether and when patients will die that usually exists in real time and excludes patients for whom high-intensity treatment was ultimately life-saving (51). However, a prospective approach is often not feasible precisely because of uncertainty about the timing of death and because of ethical and practical concerns about asking patients and their families to participate in research while they are dying (50). Lastly, our results may be biased because only slightly over one half of cohort patients had a family member who responded to the BFS. Nonetheless, this response rate is comparable to those for other similar studies (52,53) and our analyses are adjusted for nonresponse bias.

Among a national cohort of patients with advanced CKD, more intensive patterns of end-of-life care were associated with lower family ratings of quality of care, whereas receipt of hospice and palliative care services were associated with higher ratings. After adjustment for these differences, quality of end-of-life care did not vary as a function of whether patients had been treated with dialysis. A deeper understanding of what drives both patterns and quality of end-of-life care among patients with advanced CKD may help to identify opportunities to improve care for members of this population.

Disclosures

Dr. O’Hare reports receiving an honorarium from UpToDate and honoraria and reimbursement for travel from the Coalition for the Supportive Care of Kidney Patients, Dialysis Clinic, Inc., Fresenius Medical Care, Hammersmith Hospital, University of Alabama, and University of Pennsylvania. Dr. O’Hare also reports grants from National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders and Centers for Disease Control outside the submitted work. Dr. Ersek, Dr. Hebert, Dr. Liu, Dr. Reinke, Dr. Richards, Dr. Taylor, and Dr. Wachterman have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. O’Hare reports funding from a VA Merit Proposal IIR (VA IIR 12-126, PI O’Hare). Dr. Richards reports a VA Office of Academic Affiliations’ Advanced Fellowship in Health Services Research and Development (#TPH 61-000-22). Dr. Wachterman reports a grant from the National Institute of Aging (K23AG049088).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeff Todd-Stenberg and Dr. Pamela K. Greene for their expertise in data acquisition, Whitney Showalter for assistance with study coordination, Dr. Elliott Lowy for assistance with VA data, and Dawn K. Gilbert of the Veteran Experience Center data for assistance with data acquisition. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01560219/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Administrative codes for identifying treatments, procedures, and additional comorbidities (dialysis, palliative care, intensive procedures, acute hospitalizations and ICU admissions, and comorbidities).

Supplemental Appendix 2. Methods for handling missing data (unit nonresponse and item nonresponse).

Supplemental Table 1. Unadjusted proportions of end-of-life treatment patterns for overall cohort.

Supplemental Table 2. Association of dialysis treatment status with end-of-life treatment patterns.

Supplemental Table 3. Comparison of respondent and nonrespondent characteristics.

Supplemental Table 4. Unadjusted proportions for most favorable responses on Bereaved Family Survey for overall cohort.

Supplemental Table 5. Association of dialysis treatment status with most favorable responses on Bereaved Family Survey, additionally adjusted for end-of-life treatment patterns.

Supplemental Table 6. Sensitivity analysis of association of end-of-life treatment and dialysis treatment status with excellent overall care: cohort entry after September 2009.

Supplemental Table 7. Sensitivity analysis of association of dialysis treatment status with most favorable response on Bereaved Family Survey individual items: cohort entry after September 2009.

Supplemental Table 8. Demographic and clinical characteristics of those who died in VA inpatient settings versus non-VA inpatient or community settings.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: 2018 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2018/view/Default.aspx. Accessed February 26, 2019

- 2.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP: CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 260–268, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wachterman MW, Lipsitz SR, Lorenz KA, Marcantonio ER, Li Z, Keating NL: End-of-life experience of older adults dying of end-stage renal disease: A comparison with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 54: 789–797, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong SPY, Yu MK, Green PK, Liu CF, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM: End-of-life care for patients with advanced kidney disease in the US veterans affairs health care system, 2000-2011. Am J Kidney Dis 72: 42–49, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ersek M, Miller SC, Wagner TH, Thorpe JM, Smith D, Levy CR, Gidwani R, Faricy-Anderson K, Lorenz KA, Kinosian B, Mor V: Association between aggressive care and bereaved families’ evaluation of end-of-life care for veterans with non-small cell lung cancer who died in Veterans Affairs facilities. Cancer 123: 3186–3194, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, Ritchie C, Furman C, Rosenfeld K, Shreve S, Chen Z, Shea JA: Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc 56: 593–599, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, Mor V: Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 291: 88–93, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG: Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 172: 1133–1142, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murtagh FEM, Addington-Hall JM, Edmonds PM, Donohoe P, Carey I, Jenkins K, Higginson IJ: Symptoms in advanced renal disease: A cross-sectional survey of symptom prevalence in stage 5 chronic kidney disease managed without dialysis. J Palliat Med 10: 1266–1276, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Edmonds P, Donohoe P, Carey I, Jenkins K, Higginson IJ: Symptoms in the month before death for stage 5 chronic kidney disease patients managed without dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 40: 342–352, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ersek M, Smith D, Cannuscio C, Richardson DM, Moore D: A nationwide study comparing end-of-life care for men and women veterans. J Palliat Med 16: 734–740, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kutney-Lee A, Smith D, Thorpe J, Del Rosario C, Ibrahim S, Ersek M: Race/ethnicity and end-of-life care among veterans. Med Care 55: 342–351, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorpe JM, Smith D, Kuzla N, Scott L, Ersek M: Does mode of survey administration matter? Using measurement invariance to validate the mail and telephone versions of the bereaved family survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 51: 546–556, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnato AE, Farrell MH, Chang CC, Lave JR, Roberts MS, Angus DC: Development and validation of hospital “end-of-life” treatment intensity measures. Med Care 47: 1098–1105, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carpenter JG, McDarby M, Smith D, Johnson M, Thorpe J, Ersek M: Associations between timing of palliative care consults and family evaluation of care for veterans who die in a hospice/palliative care unit. J Palliat Med 20: 745–751, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, Skinner J, Bynum J, Tyler D, Mor V: End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive issues. N Engl J Med 365: 1212–1221, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foley RN, Collins AJ: The USRDS: What you need to know about what it can and can’t tell us about ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 845–851, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutney-Lee A, Brennan CW, Meterko M, Ersek M: Organization of nursing and quality of care for veterans at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 49: 570–577, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi J-C, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA: Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43: 1130–1139, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujiyoshi A, Jacobs DR Jr, Alonso A, Luchsinger JA, Rapp SR, Duprez DA: Validity of death certificate and hospital discharge ICD codes for dementia diagnosis: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 31: 168–172, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM: Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 30: 377–399, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little R: Survey nonresponse adjustments for estimates of means. Int Stat Rev 54: 139–157, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Q, Gelman A, Tracy M, Norris FH, Galea S: Incorporating the sampling design in weighting adjustments for panel attrition. Stat Med 34: 3637–3647, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. 2019 Base SAS 9.4 Reference, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

- 28.StataCorp : Stata Statistical Software: Release 15, College Station, TX, StataCorp LLC, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 29.R Core Team : R: A language and environment for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed July 15, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein D: MIMRGNS: Stata module to run margins after MI estimate, Boston, MA, Boston College Department of Economics, 2018. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457795.html. Accessed July 15, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachterman MW, Hailpern SM, Keating NL, Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM: Association between hospice length of stay, health care utilization, and medicare costs at the end of life among patients who received maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 792–799, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen S-C, Gilbertson DT, Moss AH: Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1248–1255, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen JC-Y, Thorsteinsdottir B, Vaughan LE, Feely MA, Albright RC, Onuigbo M, Norby SM, Gossett CL, D’Uscio MM, Williams AW, Dillon JJ, Hickson LJ: End of life, withdrawal, and palliative care utilization among patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1172–1179, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saeed F, Adil MM, Malik AA, Schold JD, Holley JL: Outcomes of in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation in maintenance dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 3093–3101, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladin K, Buttafarro K, Hahn E, Koch-Weser S, Weiner DE: “End-of-life care? I’m not going to worry about that yet.” Health literacy gaps and end-of-life planning among elderly dialysis patients. Gerontologist 58: 290–299, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnato AE: Challenges in understanding and respecting patients’ preferences. Health Aff (Millwood) 36: 1252–1257, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA: Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: A qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 495–503, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, Loke R, Oskoui T, Perrone RD, Meyer KB, Weiner DE, Wong JB: Discussing conservative management with older patients with ckd: An interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 627–635, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrison TG, Tam-Tham H, Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Sinnarajah A, Thomas CM: Identification and prioritization of quality indicators for conservative kidney management. Am J Kidney Dis 73: 174–183, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Lillie E, Dip SC, Cyr A, Gladish M, Large C, Silverman H, Toth B, Wolfs W, Laupacis A: Setting research priorities for patients on or nearing dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1813–1821, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD: Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 854–863, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerstel E, Engelberg RA, Koepsell T, Curtis JR: Duration of withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit and association with family satisfaction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 798–804, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khandelwal N, Curtis JR, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Engelberg RA, Teno JM: How often is end-of-life care in the United States inconsistent with patients’ goals of care? J Palliat Med 20: 1400–1404, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teno JM, Price RA, Makaroun LK: Challenges of measuring quality of community-based programs for seriously ill individuals and their families. Health Aff (Millwood) 36: 1227–1233, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Makaroun LK, Teno JM, Freedman VA, Kasper JD, Gozalo P, Mor V: Late transitions and bereaved family member perceptions of quality of end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 66: 1730–1736, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anhang Price R, Stucky B, Parast L, Elliott MN, Haas A, Bradley M, Teno JM: Development of valid and reliable measures of patient and family experiences of hospice care for public reporting. J Palliat Med 21: 924–932, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quigley DD, Elliott MN, Setodji CM, Hays RD: Quantifying magnitude of group-level differences in patient experiences with health care. Health Serv Res 53[Suppl 1]: 3027–3051, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teno JM: Measuring end-of-life care outcomes retrospectively. J Palliat Med 8[Suppl 1]: S42–S49, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bach PB, Schrag D, Begg CB: Resurrecting treatment histories of dead patients: A study design that should be laid to rest. JAMA 292: 2765–2770, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kross EK, Engelberg RA, Shannon SE, Curtis JR: Potential for response bias in family surveys about end-of-life care in the ICU. Chest 136: 1496–1502, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith D, Kuzla N, Thorpe J, Scott L, Ersek M: Exploring nonresponse bias in the department of veterans affairs’ bereaved family survey. J Palliat Med 18: 858–864, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.