Abstract

iNKT cells provide rapid innate T cell responses to glycolipid antigens from host cells and microbes. The numbers of CD1d-restricted iNKT cells are tightly controlled in mucosal tissues, but the mechanisms have been largely unclear. We found that vitamin A is a dominant factor that controls the population size of mucosal iNKT cells in mice. This negative regulation is mediated by the induction of the purinergic receptor P2X7 on iNKT cells. The expression of P2X7 is particularly high on intestinal iNKT cells, making iNKT cells highly susceptible to P2X7-mediated cell death. In vitamin A deficiency, iNKT cells fail to express P2X7, and are, therefore, resistant to P2X7-mediated cell death, leading to iNKT cell over-population. This phenomenon is most prominent in the intestine. We found that iNKT cells are divided into CD69+ sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1)− tissue-resident and CD69− S1P1+ non-resident iNKT cells. The CD69+ S1P1− tissue-resident iNKT cells highly express P2X7 and are effectively controlled by the P2X7 pathway. The regulation of iNKT cells by vitamin A by the P2X7 pathway is important to prevent aberrant expansion of effector cytokine-producing iNKT cells. Our findings identify a novel role of vitamin A in regulating iNKT cell homeostasis in many tissues throughout the body.

Introduction

The intestine provides a unique tissue environment for immune cells. The small intestine is rich in macro- and micro-nutrients, including vitamins. The intestine also hosts the gut microbiota, which regulate host physiology and the immune system by producing a myriad of metabolites. Vitamin A plays a central role in regulating intestinal immune responses, inducing regulatory T cells and lymphocytes with intestinal tissue tropism (1–4). Dietary materials and microbial metabolites contain lipid molecules that are presented by CD1d to activate iNKT cells (5–7). iNKT cells populate the intestinal tissues but their frequencies are maintained low at 0.5 to 0.05% of total lymphocytes (8, 9). However, the numbers of iNKT cells are increased in certain pathological conditions (10), implying the potential importance of iNKT homeostasis in preventing inflammatory diseases. In this regard, iNKT cells can mediate certain types of intestinal inflammation (11).

iNKT cells in the intestine can either promote or suppress immune responses to clear pathogens and tumor cells (12–15). In the intestine, many cell types including the intestinal epithelial cells, Paneth cells, dendritic cells, macrophages and B cells express CD1d (16, 17). Microbial dysbiosis occurs in iNKT-deficient mice, and this indicates that iNKT cells directly or indirectly regulate the gut microbiota (6, 18). While the commensal microbiota is regulated by iNKT cells, they can, in turn, support the normal population of iNKT cells in the intestine (19).

It is not known how the numbers of iNKT cells in the intestine and other organs are tightly regulated. iNKT cells are thought to be regulated by the balance between iNKT migration, expansion and apoptosis. iNKT cells are thought to enter peripheral tissues following certain trafficking signals (20). Diverse iNKT-activating lipid antigens in tissues can increase the numbers of iNKT cells. In this regard, limited availability of iNKT-activating antigens, along with the finite thymic output (21, 22), is likely to determine the size of peripheral iNKT cell populations. Beyond the speculation, we hardly understand how the survival and death of iNKT cells are regulated in peripheral tissues.

P2X7 is a pore-forming purinergic receptor, and its activation by adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) leads to a P2X7-dependent pyroptosis (23, 24). While ATP can activate T cells on its own, NAD-induced cell death requires an enzyme, called ADP-ribosyltransferase (ART) 2.2/ART2b, which catalyzes nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-induced adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribosylation (25). P2X7 is widely expressed in the immune system, and P2X7 deficiency leads to dysregulation of functionally specialized T helper subsets (26–29). P2X7 expression is induced on conventional T cells by all-trans retinoic acid (At-RA, hereafter called RA) (30).

We investigated the function of vitamin A in regulating iNKT cell populations. We found that vitamin A plays an overall negative role in regulating the numbers of iNKT cells in mucosal tissues, including the intestine. This negative role of vitamin A is mediated through the induction of the cell-death-inducing P2X7 receptor. We also found the existence of tissue-resident iNKT (TRN) cells. While the P2X7 pathway affects iNKT cells in most tissues, it is particularly important for TRN homeostasis in the intestine.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at University of Michigan and Purdue University. Rag1−/− C57BL/6 mice (stock number 002216) and P2rx7−/− mice (stock # 005576, called P2X7−/− mice here) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Vitamin A-deficient (VAD) and vitamin A-normal (VAN) mice were generated by feeding late-term (15-16 days post coitus) pregnant females with AIN-93G-based custom diet containing retinyl acetate at 2,500 IU/kg of diet for VAN or 0 IU/kg of diet for VAD respectively (TD. 07267 and TD. 00158, Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN). Mice were weaned at 3 weeks of age and maintained on the same diet for at least 7 additional weeks prior to examination of iNKT cells.

Cell isolation

When indicated, mice were injected i.v. with a single-domain blocking antibody (50 μg per mouse, ART2.2 Nanobody, BioLegend) 30 min prior to euthanasia (31). Most experiments were performed without using the nanobody. For intestinal cells, tissues were cut open longitudinally and washed with cold PBS. Small intestinal tissues were processed after removing Peyer’s patches. The washed tissues were further cut into 1-2 cm long pieces and treated three times with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution containing 1 mM EDTA, 2% HEPES and 0.35g/L NaHCO3 to remove epithelial cells. The tissues were digested by collagenase IV (1.5 mg/mL) containing 10% newborn calf serum for 45 min at 37°C to make lamina propria cell suspensions. Spleen, MLN, liver, lung and thymus were cut into small pieces by chopping with scissors and then made into cell suspensions with fine iron meshes. The cell suspensions were collected in tubes for 5-10 min on ice, and single cell suspensions, free of aggregated cells and tissues that settle down, were used for flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with anti-P2X7 (clone Hano43, AbD Serotec), anti-rat IgG2b (clone MRG 2b-85), PerCP/Cy5.5 or PE-Cy7 conjugated streptavidin, anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), anti-IFNγ (clone XMG1.2), anti-IL17 (clone TC11-18H10.1), anti-IL-9 (clone RM9A4), anti-IL-4 (clone 11B11), anti-TCRβ (clone H57-597), anti-S1PR1 (clone 713412), anti-CD45.1 (clone A20 ), anti-CD45.2 (clone 104), anti-CD3 (clone 17A2), anti-CD44 (clone IM7), anti-PLZF (clone 9E12), anti-CD69 (clone H1.2F3), anti-RORγt (clone AFKJS-9), anti-T-bet (clone eBio-4B10), and/or PE or APC labeled OCH- loaded CD1d tetramers (the NIH Tetramer Facility). Most antibodies were purchased from BioLegend or eBioscience. For detections of P2X7 on iNKT cells, cells were sequentially stained with anti-P2X7 antibody, PE conjugated anti-rat IgG2b, and/or intracellular staining of cytokines. Intracellular staining of cytokines and other antigens were performed as described previously (32). Gating information based on the expression of TCRβ, CD1d-tetramer, RORγt and PLZF for NKT1 (RORγt− PLZF−), NKT2 (RORγt− PLZF+), and NKT17 (RORγt+ PLZF+) subsets is shown in Fig. S1A.

In vivo activation and measurement of serum cytokines

Mice were injected with OCH (an α-GalCer analogue, 5 μg/mouse) i.g. or i.v. and were euthanized 24h later. Cytokine-producing iNKT cells in the intestine and other organs were examined by flow cytometry as described above. Blood plasma was examined for the levels of IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ by Legendplex beads (BioLegend).

Cell division assay

Total splenocytes were labeled with the CFSE cell division tracker kit (BioLegend) and cells were cultured in RPMI containing 20% regular fetal calf serum with or without RA (20 nM), OCH (200 ng/ml) and IL-2 (100 u/ml) for 24h. The cultured cells were centrifuged through an underlay of newborn calf serum (100%) in for 7 min and were further cultured without OCH but with IL-2 for 3 additional days in the presence or absence of RA. Cells were harvest and analyzed for the CFSE intensity of CD1d-Tet+ cells by flow cytometry.

Measuring iNKT populating ability in Rag1−/− mice

Splenocytes were first depleted of B220+ cells and CD11c+ cells using FITC-labeled anti-B220 and anti-CD11c antibodies and anti-FITC magnetic beads. The B/dendritic cell-depleted cells were further stained with a PE-conjugated PBS-57- loaded CD1d tetramers for 1 hour on ice and further stained with anti-PE magnetic beads. CD1d-teramer+ iNKT cells were enriched with an AutoMACS. Equal numbers (1×106 cells each) of enriched iNKT cells (~30% were CD1d-Tetramer+), isolated from CD45.1+ wild type (WT) and CD45.2+ P2X7−/− C57BL/6 mice, were co-injected i.v. into a Rag1−/− C57BL/6 host mouse. Mice were euthanized 3 weeks later. The numbers of iNKT cell subsets in various organs were determined by flow cytometry.

Parabiosis mice

Upon weaning at 3 weeks of age, 2 mice were co-housed for 2 weeks and paired to make parabiosis mice. The surgery and maintenance details for the paired mice were described previously (33). Parabiosis mice were sacrificed 4 (CD45.1 and CD45.2) or 8 (WT and P2X7−/−) weeks after the surgery.

NAD-induced iNKT cell death

Freshly isolated or cultured iNKT cells were treated with NAD (β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide hydrate, Sigma-Aldrich, 100 μM) for 2 hours in complete cRPMI-1640. Cells were then washed twice with ice cold PBS, and then stained with OCH-loaded CD1d tetramers and anti-TCRβ antibody. When indicated, Annexin V and PI staining was performed in Annexin V binding buffer (BioLegend). To assess the short-term depletion effect of NAD on iNKT cells in vivo, mice were injected i.v. with NAD (10 mg) and sacrificed 20 hours later.

Confocal microscopy

SI tissues (ileum) were frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA). Frozen tissue blocks were cut into 8 μm-sections, fixed in acetone and stained with PBS-57- loaded CD1d tetramers and antibodies to CD3 and pan-cytokeratin. The images were obtained with a Nikon A1 confocal system. The numbers of iNKT cells in small intestinal villi were counted using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Data from 2-4 experiments were combined (n=4-7). Statistical significances of differences between indicated groups were determined by Student’s t-test (Prism 7.0). P values <0.05 were considered significant in all figures. All error bars indicate SEM.

Results

Over-population of iNKT cells in vitamin A deficiency.

To determine the effect of vitamin A metabolites on iNKT cells, we prepared vitamin A-deficient (VAD) mice by feeding near-term pregnant female mice and their pups with an AIN93G-based vitamin A-free diet (0 retinol IU/Kg) for ~10 weeks. Control mice were fed a vitamin A normal (VAN) diet (2500 retinol IU/Kg). The iNKT cell frequencies and numbers in the small intestine (SI) were considerably increased in VAD mice (Fig. 1A, S1A). The positive effect of VAD on iNKT cells was also detected in the lung, MLN, and large intestine (LI) (Fig. S1B). The effect on spleen iNKT cells was generally not significant, but the numbers of spleen iNKT17 cells were still increased (Fig. 1A). The negative impact of vitamin A is interesting, and we examined if RA, the active metabolite of vitamin A, has any negative effect on iNKT cell proliferation. However, RA had no detectable effect on OCH (an αGalCer analogue)-induced iNKT cell proliferation (Fig. S1C). This indicates that vitamin A metabolites may control iNKT cells through other mechanisms.

Fig. 1. iNKT cell dysplasia in vitamin A deficiency and differential expression of P2X7 by iNKT cells of different tissues.

(A) Numbers of CD1d-Tetramer+ iNKT cells in the spleen and small intestine (SI) of vitamin A-deficient (VAD) versus normal (VAN) mice. Mice were fed VAN or VAD diets for 10-12 weeks from birth and examined for indicated iNKT cells. (B, C) P2X7 is highly expressed by CD1d-Tetramer+ iNKT cells in the intestines and MLN. Representative and combined data (n=6 for A; n=4 for C) are shown. All error bars indicate SEM. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) from control or between two groups.

Tissue-dependent expression of P2X7 by iNKT cells.

Increased apoptosis is a potential mechanism to negatively regulate iNKT cell populations. RA induces the expression of the membrane pore-forming P2X7 receptor in conventional T cells and makes them susceptible to ATP and NAD-induced cell death (30). Therefore, we examined if P2X7 expression on iNKT cells is also regulated by vitamin A metabolites.

First, we examined P2X7 expression by iNKT cells in various organs including the thymus, liver, spleen, lungs, MLN, LI and SI. We found that iNKT cells of different organs expressed P2X7 at different levels (Fig. 1B, C). iNKT cells in mucosal tissues relatively more highly expressed P2X7 than those in systemic organs such as the liver and spleen. Particularly, greater than 95% of iNKT cells in SI expressed P2X7, whereas only ~15% of iNKT cells in the thymus expressed P2X7 (Fig. 1B, C). All iNKT cell subsets, such as iNKT1, iNKT2, and iNKT17, highly expressed P2X7 in SI and LI. iNKT17 cells highly expressed P2X7 also in the MLN (Fig. 1B, C). In general, the expression of P2X7 by iNKT cells in the thymus, liver, and spleen were significantly lower than those in the intestines. iNKT cells in the lungs, another mucosal tissue, expressed P2X7 at intermediate levels.

Vitamin A metabolites are required for normal expression of P2X7 on iNKT cells.

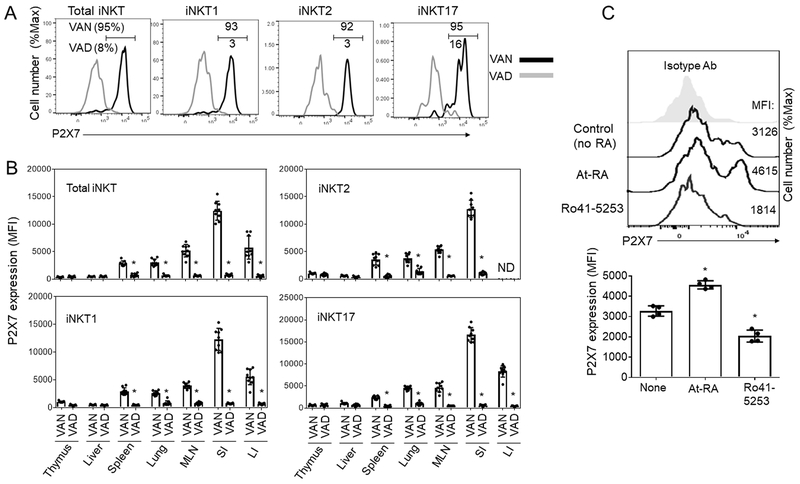

We, next, determined if the P2X7 expression by iNKT cells is altered in vitamin A deficiency. We found that P2X7 expression in all organs, including those in the intestines, was suppressed to basal levels in vitamin A deficiency (Fig. 2A, B). This suppression of P2X7 expression in vitamin A deficiency was clear on all NKT subsets, such as iNKT1, iNKT2 and iNKT17 subsets.

Fig. 2. Vitamin A is required for normal expression of P2X7 by iNKT cells.

(A) P2X7 expression by indicated CD1d-Tetramer+ iNKT cells in the intestine of VAN versus VAD mice. (B) P2X7 expression by iNKT cells of VAN versus VAD mice. (C) Impact of RARα agonist and antagonist on P2X7 expression by iNKT cells. Splenocytes were cultured in the presence of IL-2 and RA or Ro-41-5253 for 4 days, and P2X7 expression by CD1d-Tet+ iNKT cells were examined (n=4). OCH was added during the first 24 h for cell stimulation. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) from VAN or control groups.

We studied the possibility that RA directly induces P2X7 expression on iNKT cells. We found that spleen iNKT cells, which express P2X7 at low levels, up-regulated P2X7 expression when they were treated with RA along with an NKT cell-activating lipid antigen, OCH, for 4 days (Fig. 2C). In contrast, Ro41-5253, an RARα antagonist, had a negative effect on P2X7 expression on iNKT cells.

P2X7 activation induces iNKT cell-death.

P2X7 activation leads to the influx of calcium and sodium ions, and this process inhibits key enzymes responsible for maintaining phosphatidylserine on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, leading to cell death (34, 35). WT iNKT cells, isolated from small intestinal tissues, were susceptible to NAD-induced cell death in vitro (Fig. 3A). In contrast, P2X7−/− iNKT cells were largely resistant to NAD-induced cell death. We also administered NAD i.v. into mice to determine if this induces depletion of iNKT cells. NAD administration effectively decreased iNKT cell numbers in the small intestine of WT but not that of P2X7−/− mice (Fig. 3B). Small and large intestinal iNKT cell subsets, particularly iNKT17 cells, were effectively depleted by NAD in vivo (Fig. 3B, S2A, S2B). Lung iNKT cells were also significantly depleted, but those in the spleen and liver were largely unaffected (Fig. S2A, B). This indicates that mucosal iNKT cells are preferentially controlled by P2X7-mediated death.

Fig. 3. P2X7 activation-induced death of iNKT cells in WT versus P2X7−/− mice.

(A) Ex vivo cell death of iNKT cells, isolated from the SI of WT and P2X7−/− mice, in response to NAD. Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining was performed. (B) In vivo depletion of iNKT cells in the small intestine of WT and P2X7−/− mice 1 day after NAD injection. Absolute cell numbers are shown (n=4). *Significant differences (P values <0.05) from WT or control mice.

P2X7 controls the tissue population ability of iNKT cells and levels of iNKT-derived effector cytokines.

To determine the in vivo effect of P2X7 on iNKT cell populations, we examined the numbers of iNKT cells in various tissues of P2X7−/− mice. iNKT cells were numerically increased in the small intestinal villi of P2X7−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig.4A, B). All three iNKT cell subsets in both the small and large intestines were significantly increased (Fig. 4B). Also, the numbers of iNKT cells in the MLN but not in the spleen were significantly increased in P2X7−/− mice compared to WT mice (Fig. S3A). It has been reported that blocking of the P2X7 pathway with a single-chain antibody that targets ART2.2 increased the yield of iNKT cell isolation from tissues (36, 37). One reason for the observed differences between WT and P2X7−/− mice in this study could be due to increased survival of P2X7−/− iNKT cells over their WT counterpart during cell isolation. To rule out this possibility, we assessed iNKT cell numbers in the intestine and other tissues following the injection with an ART2.2 blocking single chain antibody. We found that the blocking improved the iNKT cell yield from the small intestine of WT mice by ~25%, but the cell numbers from WT mice were still considerably smaller than that from P2X7−/− mice (Fig. 4C). We did not see significant effects of the ART2.2 blockade on iNKT cell yields from other organs (Fig. S3B, C). Thus, the differences between WT and P2X7−/− iNKT cells are largely due to differences in cell numbers in vivo rather than in iNKT cell survival during cell isolation.

Fig. 4. Increased numbers of iNKT cells in the intestine of P2X7−/− mice.

(A) Comparison of WT and P2X7−/− mice for iNKT cells in the small intestinal villi in the ileum. CD1d+Teramer+ cells per 10,000 μm2 of lamina propria areas were counted. Cell counts for 18 villi from 3 mice are shown for each group. (B) Numbers of iNKT cells and iNKT cell subsets in the lamina propria of SI and LI. (C, D) Numbers of iNKT cells in WT and P2X7−/− mice following ART2.2 blockade. Anti-ART2.2 single chain antibody was injected i.v. into mice 30 min before euthanasia. Combined data (n=6 for B, n=4 for D) are shown. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) from wild type control mice.

Also increased were iNKT cells expressing effector cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-4, IL-9 and IL-17 at both steady state and following oral OCH administration (Fig. 5A, B). Blood cytokine measurements indicate that overall increased production of effector cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-2, and IL-4 at steady state and following OCH administration i.v or i.g. (Fig. 5C). While not all of the increased levels of cytokines are from iNKT cells, these data suggest that there is an over-population of iNKT cells. To directly measure the relative populating ability of WT versus P2X7−/− iNKT cells, we co-injected iNKT-enriched cells, isolated from the spleens of WT and P2X7−/− mice, into T/B cell-deficient Rag1−/− mice and examined the relative frequencies of WT and P2X7−/− iNKT cells in the recipients 3 weeks later. We found P2X7−/− iNKT cells were dominant over WT iNKT cells in populating the intestines and MLN (Fig. 6A, B). Relatively smaller effects of P2X7 were observed for iNKT2 in the lung and spleen, and for iNKT1 cells in the lung, liver and spleen (Fig. 6B). Overall, P2X7 has a powerful negative effect on iNKT cells in the intestine and weaker but significant effects on iNKT cells in other tissues.

Fig. 5. Over-production of iNKT cell-derived effector cytokines in P2X7−/− mice.

(A, B) Comparison of WT and P2X7−/− mice for iNKT cells producing indicated cytokines in the small intestinal lamina propria. Frequency of iNKT cells producing indicated cytokines in the small intestinal lamina propria is shown. Mice were injected with OCH i.g. and examined 24 hours later. (C) Cytokine concentrations in the blood plasma in WT versus P2X7−/− mice were determined. Mice were injected with OCH i.g. or i.v. and examined 24 hours later. Representative and combined data (n=4) are shown. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) between two groups.

Fig. 6. P2X7−/− iNKT cells have greatly increased population potentials.

(A) Competitive population of WT and P2X7−/− iNKT cells in the population of indicated organs. Enriched CD1d-Tet+ cells were isolated from the spleen tissues of WT and P2X7−/− mice and were injected into Rag1-deficient mice. The mice were euthanized 3 weeks later, and iNKT cell numbers in indicated tissues were determined by flow cytometry. (B) Competitive population of WT and P2X7−/− iNKT subsets in the indicated organs. Representative and combined data (n=6) are shown.

P2X7 activation effectively depletes tissue-resident iNKT cells in the intestine.

Conventional T cells, in general, are highly migratory but certain memory and effector T cell subsets tend to reside in tissues rather than circulate through the blood-lymphoid system. These T cells are called tissue-resident memory T cells and play important roles in responding to pathogens and antigens in tissues (38). Similar to conventional T cells, iNKT cells are also divided into CD69+ and CD69− cells in the intestinal lamina propria (Fig. 7). This applies to all iNKT cell subsets in lymphoid and intestinal tissues (Fig. S4A). Interestingly, CD69+ iNKT cells more highly expressed P2X7 than CD69− iNKT cells (Fig. 7A). The CD69+ iNKT cells from the intestinal lamina propria largely lacked the expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) (Fig. 7B), a G-protein-coupled chemoattractant receptor for tissue emigration of lymphocytes following S1P gradients (39). This suggests that CD69+ iNKT cells are tissue-resident cells.

Fig. 7. Tissue-resident CD69+ iNKT cells highly express P2X7 and are effectively controlled by P2X7.

(A) Expression of P2X7 by CD69− and CD69+ iNKT cells. (B) Expression of S1PR1 by CD69− and CD69+ iNKT cells. (C) Replacement rates of CD69− and CD69+ iNKT cells by non-host-derived iNKT cells in indicated tissues of parabiosis mice. CD69− and CD69+ iNKT cells in parabiosis mice between congenic CD45.1 and CD45.2 WT mice. (D) Abnormal expansion of CD69+ iNKT cells in P2X7-deficient mice. (E) Comparison of the population of CD69− and CD69+ iNKT cells in the parabiosis mice between WT CD45.1 and P2X7−/− CD45.2 mice. Representative and combined data (n=3-7) are shown. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) from control groups.

Parabiosis mice with joined blood circulation between two mice are commonly used to assess turnover rates and tissue residency of immune cells. To determine the tissue-residency of CD69+ vs. CD69− iNKT cells, we performed a parabiosis study between CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ congenic mice to compare the relative population ability of CD69+ and CD69− iNKT cells. CD69+ iNKT cells in all the tissues examined were slower to be replaced with non-host-derived cells, compared to CD69− iNKT cells (Fig. 7C, S4B). This indicates that CD69+ iNKT cells have relatively more stable tissue residency (i.e. lower turnover rates), thus satisfying the phenotype of TRN cells. In the intestines of P2X7−/− mice, the numbers of CD69+ iNKT cells were greatly increased, while the numbers of CD69− iNKT cells were not changed or only slightly increased (Fig. 7D). The enrichment of CD69+ over CD69− iNKT cells was also observed in the spleen and MLN but at low magnitudes compared to that of the intestines (Fig. S4C). We further performed a parabiosis study between WT and P2X7−/− mice to determine the impact of P2X7 on the population behavior of iNKT cells in animals with an intact immune system. While WT CD69− iNKT cells were readily replaced with their P2X7−/− counterpart, P2X7−/− CD69− iNKT cells were not readily replaced with their WT counterpart (Fig. 7E). This indicates that P2X7 negatively regulates the population of the migratory iNKT cells. Similar, but smaller, differences between WT and P2X7−/− mice for CD69+ iNKT cells confirm the negative role of P2X7 on TRN cells as well (Fig. 7C). Importantly, the effect of P2X7 was detected in many tissues of the parabiosis mice beyond the intestine, suggesting a potentially comprehensive role for P2X7 in regulating iNKT cell populations throughout the body.

Effects of vitamin A on intestinal iNKT cells in the absence of P2X7.

Because vitamin A metabolites may regulate intestinal iNKT cells in both positive and negative ways, there is a need to determine how much of the effect of vitamin A deficiency is due to the decreased expression of P2X7. We assessed the impact of vitamin A deficiency on iNKT cell numbers in P2X7−/− mice. If the P2X7 pathway is a dominant regulatory mechanism for intestinal iNKT cells, vitamin A deficiency would not increase iNKT numbers in P2X7-deficient mice. Rather than increasing iNKT cell numbers in vitamin A deficiency, iNKT numbers were actually decreased in the small intestine of VAD, compared to VAN, P2X7−/−mice (Fig. 8). However, we found no significant changes in the numbers of iNKT cells in other tissues of P2X7-deficient mice in vitamin A deficiency. The data suggest that in the absence of the dominant P2X7 effect, vitamin A can even exert a positive effect on the numbers of intestinal iNKT cells.

Fig. 8. Vitamin A deficiency fails to increase the numbers of iNKT cells in the absence of P2X7 expression.

Comparison of the numbers of P2X7−/− iNKT cells in vitamin A normal (VAN) and deficient (VAD) conditions. P2X7−/− mice were fed VAN or VAD diet for 11 weeks from birth and examined for indicated iNKT cells. Combined data (n=5-6) are shown. All error bars indicate SEM. *Significant differences (P values <0.05) between two groups.

Discussion

We found that iNKT cells over-populate mucosal tissues, particularly the intestine in vitamin A deficiency, and found a mechanism for the phenomenon. The over-population of iNKT cells is largely due to defective P2X7 expression, because P2X7 expression on iNKT cells is induced by vitamin A metabolites. P2X7 activation induces iNKT cell death, and thereby restraining the size of iNKT cell populations in high RA conditions. This pathway of iNKT cell regulation is important for the homeostasis of iNKT cells.

The negative effect of vitamin A on iNKT populations is intriguing. Thus far, the role of vitamin A status on iNKT cells has been unclear. In one article, increased expression of CD1d on a myeloid cell line by RA was observed in vitro (40). It has been also reported that parenteral injection of RA decreased cytokine production by iNKT cells and related liver damage (41). The increase of iNKT cell populations in vitamin A deficiency revealed in our study is somewhat similar to the ILC2 expansion in vitamin A deficiency (42, 43). In contrast, the numbers of ILC3 and conventional T cells were decreased in vitamin A deficiency (44). Our findings indicate that all subsets of iNKT cells (i.e. iNKT½/17) are regulated by vitamin A metabolites. Among the subsets, iNKT17 cells appear to be particularly more sensitive.

At the molecular level, the mouse P2X7 gene has an enhancer region between exon 2 and 3 for the binding by RARα and activation by RA (30), and this explains the up-regulation of P2X7 on iNKT cells by vitamin A metabolites. iNKT cells are highly susceptible to NAD-induced cell death. Liganded P2X7 molecules form pores on cellular membrane to disturb the integrity of the cellular membrane essential for cell survival. P2X7 activation in mononuclear cells involves inflammasomes and subsequent caspase 1 activation for cell death, which is called pyroptosis. The intestine has high levels of ATP, which is mainly produced from gut bacteria (45, 46). Significant levels of NAD are present in body fluids including the blood plasma (47). Together with the high level of P2X7 expression by intestinal iNKT cells, this creates an effective environment to control iNKT cells.

Vitamin A deficiency causes a T-B cell lymphopenia in the intestine (44, 48). This is explained, in part, by the function of vitamin A metabolites in promoting the homing of lymphocytes to the intestine and by the role of RA in supporting T cell effector function (49, 50). However, this function of vitamin A fails to account for the increased iNKT cells in vitamin A deficiency. In P2X7-deficient mice, vitamin A deficiency contradictorily decreased the numbers of intestinal iNKT cells. This indicates that intestinal iNKT cells are also positively regulated by vitamin A metabolites, but this function is masked by the relatively more dominant P2X7-dependent negative regulation. The positive function of vitamin A metabolites is likely to be mediated, in part, by the well-established function of RA in promoting the gut-homing behavior of lymphocytes (48).

In conjunction with the P2X7-regualtion, we found that there are tissue-resident iNKT cells in the intestine and other tissues. Immune cells, particularly T cells, can be divided into circulating and tissue-resident memory cells (38, 51). Tissue-resident T cells typically express CD69 and lack S1PR1 (52, 53). We provided evidence that CD69+ iNKT cells are bona fide tissue-resident cells with low turnover rates in tissues. Tissue-resident CD69+ iNKT cells are greatly increased in the intestine of P2X7-deficient mice. In wild type mice, most of CD69+ iNKT cells highly express P2X7 but largely lack S1PR1 expression, whereas not all CD69− iNKT cells express P2X7. Thus, tissue-resident CD69+ iNKT cells are a major target of the P2X7-mediated iNKT cell control. The parabiosis study between WT and P2X7−/− mice revealed that P2X7 also negatively regulates circulating CD69− iNKT cells in most organs.

iNKT cells can protect from pathogens but can also mediate inflammatory responses (54). Therefore, the expansion of iNKT cells in the intestine due to decreased expression of P2X7 is expected to significantly influence the intestinal immune system. P2X7 deficiency affects most subsets of iNKTs, including iNKT1, iNKT2, and iNKT17. Considering the fact that immune responses to pathogens typically induce a polarized response mainly mediated by a specific subset, the non-specific expansion of iNKT cell subsets, each producing effector cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-4, IL-9 and/or IL-17, could even perturb the functions of specialized iNKT and other immune cells. In this regard, the impact of the abnormal iNKT expansion on tissue inflammation and immune responses against pathogens and tumor cells should be investigated further.

In summary, iNKT cells are negatively regulated by vitamin A metabolites. RA induces P2X7 expression on iNKT cells in the intestine where RA is highly produced. Among iNKT cells, CD69+ S1PR1− tissue-resident iNKT cells particularly highly express P2X7. This leads to effective control of tissue-resident intestinal iNKT cells, a process important for homeostatic regulation of tissue iNKT cells. Finally, the regulatory function of P2X7 appears to reach beyond the intestine, affecting the population of iNKT cells in many other organs.

Supplementary Material

Key points:

Vitamin A negatively regulates iNKT cell population

P2X7 up-regulation by retinoic acid makes iNKT cells sensitive to cell death

Tissue-resident iNKT cells are preferentially controlled by P2X7 activation.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Leon Friesen, Rana Bikash and Ali Sepahi (University of Michigan) for their input. We thank the NIH tetramer facility for providing CD1d-tetramers. CK is the Judy and Kenneth Betz Endowed Professor in the Mary H Weiser Food Allergy Center.

Grant support: This study was supported, in part, by grants from the NIH (1R01AI121302, 1R01DK076616, R01AI080769, and1R01AI074745 to CHK).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: MLN, Mesenteric Lymph Node; LI, Large Intestine; RA, Retinoic Acid; S1PR1, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 1; SI, Small Intestine; TRN, CD69+ tissue-resident NKT; WT, wild type

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kim CH 2018. Control of Innate and Adaptive Lymphocytes by the RAR-Retinoic Acid Axis. Immune Netw 18: e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mora JR, Iwata M, and von Andrian UH. 2008. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 685–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwata M 2009. Retinoic acid production by intestinal dendritic cells and its role in T-cell trafficking. Semin Immunol 21: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raverdeau M, and Mills KH. 2014. Modulation of T cell and innate immune responses by retinoic Acid. J Immunol 192: 2953–2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An D, Oh SF, Olszak T, Neves JF, Avci FY, Erturk-Hasdemir D, Lu X, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS, and Kasper DL. 2014. Sphingolipids from a symbiotic microbe regulate homeostasis of host intestinal natural killer T cells. Cell 156: 123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saez de Guinoa J, Jimeno R, Gaya M, Kipling D, Garzon MJ, Dunn-Walters D, Ubeda C, and Barral P. 2018. CD1d-mediated lipid presentation by CD11c(+) cells regulates intestinal homeostasis. EMBO J. 37: e97537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossjohn J, Pellicci DG, Patel O, Gapin L, and Godfrey DI. 2012. Recognition of CD1d-restricted antigens by natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 12: 845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Keeffe J, Doherty DG, Kenna T, Sheahan K, O’Donoghue DP, Hyland JM, and O’Farrelly C. 2004. Diverse populations of T cells with NK cell receptors accumulate in the human intestine in health and in colorectal cancer. Eur J Immunol 34: 2110–2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bannai M, Kawamura T, Naito T, Kameyama H, Abe T, Kawamura H, Tsukada C, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K, Hamada H, Nishiyama Y, Ishikawa H, Takeda K, Okumura K, Taniguchi M, and Abo T. 2001. Abundance of unconventional CD8(+) natural killer T cells in the large intestine. Eur J Immunol 31: 3361–3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grose RH, Thompson FM, Baxter AG, Pellicci DG, and Cummins AG. 2007. Deficiency of invariant NK T cells in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 52: 1415–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuss IJ, Heller F, Boirivant M, Leon F, Yoshida M, Fichtner-Feigl S, Yang Z, Exley M, Kitani A, Blumberg RS, Mannon P, and Strober W. 2004. Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest 113: 1490–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingender G, and Kronenberg M. 2008. Role of NKT cells in the digestive system. IV. The role of canonical natural killer T cells in mucosal immunity and inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeissig S, Kaser A, Dougan SK, Nieuwenhuis EE, and Blumberg RS. 2007. Role of NKT cells in the digestive system. III. Role of NKT cells in intestinal immunity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G1101–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izhak L, Ambrosino E, Kato S, Parish ST, O’Konek JJ, Weber H, Xia Z, Venzon D, Berzofsky JA, and Terabe M. 2013. Delicate balance among three types of T cells in concurrent regulation of tumor immunity. Cancer Res 73: 1514–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Sedimbi S, Lofbom L, Singh AK, Porcelli SA, and Cardell SL. 2018. Unique invariant natural killer T cells promote intestinal polyps by suppressing TH1 immunity and promoting regulatory T cells. Mucosal Immunol 11: 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleicher PA, Balk SP, Hagen SJ, Blumberg RS, Flotte TJ, and Terhorst C. 1990. Expression of murine CD1 on gastrointestinal epithelium. Science 250: 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monzon-Casanova E, Steiniger B, Schweigle S, Clemen H, Zdzieblo D, Starick L, Muller I, Wang CR, Rhost S, Cardell S, Pyz E, and Herrmann T. 2010. CD1d expression in paneth cells and rat exocrine pancreas revealed by novel monoclonal antibodies which differentially affect NKT cell activation. PLoS One 5: e13089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvanantham T, Lin Q, Guo CX, Surendra A, Fieve S, Escalante NK, Guttman DS, Streutker CJ, Robertson SJ, Philpott DJ, and Mallevaey T. 2016. NKT Cell-Deficient Mice Harbor an Altered Microbiota That Fuels Intestinal Inflammation during Chemically Induced Colitis. J Immunol 197: 4464–4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei B, Wingender G, Fujiwara D, Chen DY, McPherson M, Brewer S, Borneman J, Kronenberg M, and Braun J. 2010. Commensal microbiota and CD8+ T cells shape the formation of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol 184: 1218–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slauenwhite D, and Johnston B. 2015. Regulation of NKT Cell Localization in Homeostasis and Infection. Front Immunol 6: 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lantz O, and Bendelac A. 1994. An invariant T cell receptor alpha chain is used by a unique subset of major histocompatibility complex class I-specific CD4+ and CD4-8- T cells in mice and humans. J Exp Med 180: 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, and Kronenberg M. 2001. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat Immunol 2: 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang D, He Y, Munoz-Planillo R, Liu Q, and Nunez G. 2015. Caspase-11 Requires the Pannexin-1 Channel and the Purinergic P2X7 Pore to Mediate Pyroptosis and Endotoxic Shock. Immunity 43: 923–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg TH, Newman AS, Swanson JA, and Silverstein SC. 1987. ATP4- permeabilizes the plasma membrane of mouse macrophages to fluorescent dyes. J Biol Chem 262: 8884–8888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adriouch S, Bannas P, Schwarz N, Fliegert R, Guse AH, Seman M, Haag F, and Koch-Nolte F. 2008. ADP-ribosylation at R125 gates the P2X7 ion channel by presenting a covalent ligand to its nucleotide binding site. FASEB J 22: 861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheuplein F, Schwarz N, Adriouch S, Krebs C, Bannas P, Rissiek B, Seman M, Haag F, and Koch-Nolte F. 2009. NAD+ and ATP released from injured cells induce P2X7-dependent shedding of CD62L and externalization of phosphatidylserine by murine T cells. J Immunol 182: 2898–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proietti M, Cornacchione V, Rezzonico Jost T, Romagnani A, Faliti CE, Perruzza L, Rigoni R, Radaelli E, Caprioli F, Preziuso S, Brannetti B, Thelen M, McCoy KD, Slack E, Traggiai E, and Grassi F. 2014. ATP-gated ionotropic P2X7 receptor controls follicular T helper cell numbers in Peyer’s patches to promote host-microbiota mutualism. Immunity 41: 789–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heiss K, Janner N, Mahnss B, Schumacher V, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F, and Mittrucker HW. 2008. High sensitivity of intestinal CD8+ T cells to nucleotides indicates P2X7 as a regulator for intestinal T cell responses. J Immunol 181: 3861–3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aswad F, Kawamura H, and Dennert G. 2005. High sensitivity of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells to extracellular metabolites nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and ATP: a role for P2X7 receptors. J Immunol 175: 3075–3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto-Hill S, Friesen L, Kim M, and Kim CH. 2017. Contraction of intestinal effector T cells by retinoic acid-induced purinergic receptor P2X7. Mucosal Immunol 10: 912–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rissiek B, Danquah W, Haag F, and Koch-Nolte F. 2014. Technical Advance: a new cell preparation strategy that greatly improves the yield of vital and functional Tregs and NKT cells. J Leukoc Biol 95: 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang SG, Lim HW, Andrisani OM, Broxmeyer HE, and Kim CH. 2007. Vitamin A metabolites induce gut-homing FoxP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol 179: 3724–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kamran P, Sereti KI, Zhao P, Ali SR, Weissman IL, and Ardehali R. 2013. Parabiosis in mice: a detailed protocol. J. Vis. Exp 80: 50556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Courageot MP, Lepine S, Hours M, Giraud F, and Sulpice JC. 2004. Involvement of sodium in early phosphatidylserine exposure and phospholipid scrambling induced by P2X7 purinoceptor activation in thymocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 21815–21823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bratton DL, Fadok VA, Richter DA, Kailey JM, Guthrie LA, and Henson PM. 1997. Appearance of phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cells requires calcium-mediated nonspecific flip-flop and is enhanced by loss of the aminophospholipid translocase. J Biol Chem 272: 26159–26165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tamayose K, Hirai Y, and Shimada T. 1996. A new strategy for large-scale preparation of high-titer recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors by using packaging cell lines and sulfonated cellulose column chromatography. Hum Gene Ther 7: 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borges da Silva H, Wang H, Qian LJ, Hogquist KA, and Jameson SC. 2019. ARTC2.2/P2RX7 Signaling during Cell Isolation Distorts Function and Quantification of Tissue-Resident CD8(+) T Cell and Invariant NKT Subsets. J Immunol 202: 2153–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mueller SN, and Mackay LK. 2016. Tissue-resident memory T cells: local specialists in immune defence. Nat Rev Immunol 16: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baeyens A, Fang V, Chen C, and Schwab SR. 2015. Exit Strategies: S1P Signaling and T Cell Migration. Trends Immunol 36: 778–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Q, and Ross AC. 2015. All-trans-retinoic acid and CD38 ligation differentially regulate CD1d expression and alpha-galactosylceramide-induced immune responses. Immunobiology 220: 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KA, Song YC, Kim GY, Choi G, Lee YS, Lee JM, and Kang CY. 2012. Retinoic acid alleviates Con A-induced hepatitis and differentially regulates effector production in NKT cells. Eur J Immunol 42: 1685–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim MH, Taparowsky EJ, and Kim CH. 2015. Retinoic Acid Differentially Regulates the Migration of Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets to the Gut. Immunity 43: 107–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Yang Q, Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Boyd A, Nutman TB, Urban JF Jr., Wang J, Ramalingam TR, Bhandoola A, Wynn TA, and Belkaid Y. 2014. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science 343: 432–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mielke LA, Jones SA, Raverdeau M, Higgs R, Stefanska A, Groom JR, Misiak A, Dungan LS, Sutton CE, Streubel G, Bracken AP, and Mills KH. 2013. Retinoic acid expression associates with enhanced IL-22 production by gammadelta T cells and innate lymphoid cells and attenuation of intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med 210: 1117–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iwase T, Shinji H, Tajima A, Sato F, Tamura T, Iwamoto T, Yoneda M, and Mizunoe Y. 2010. Isolation and identification of ATP-secreting bacteria from mice and humans. J Clin Microbiol 48: 1949–1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atarashi K, Nishimura J, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Yamamoto M, Onoue M, Yagita H, Ishii N, Evans R, Honda K, and Takeda K. 2008. ATP drives lamina propria T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature 455: 808–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuwatari T, and Shibata K. 2009. Consideration of diurnal variations in human blood NAD and NADP concentrations. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 55: 279–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iwata M, Hirakiyama A, Eshima Y, Kagechika H, Kato C, and Song SY. 2004. Retinoic acid imprints gut-homing specificity on T cells. Immunity 21: 527–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown CC, Esterhazy D, Sarde A, London M, Pullabhatla V, Osma-Garcia I, Al-Bader R, Ortiz C, Elgueta R, Arno M, de Rinaldis E, Mucida D, Lord GM, and Noelle RJ. 2015. Retinoic acid is essential for Th1 cell lineage stability and prevents transition to a Th17 cell program. Immunity 42: 499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall JA, Cannons JL, Grainger JR, Dos Santos LM, Hand TW, Naik S, Wohlfert EA, Chou DB, Oldenhove G, Robinson M, Grigg ME, Kastenmayer R, Schwartzberg PL, and Belkaid Y. 2011. Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity 34: 435–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosato PC, Beura LK, and Masopust D. 2017. Tissue resident memory T cells and viral immunity. Curr Opin Virol 22: 44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skon CN, Lee JY, Anderson KG, Masopust D, Hogquist KA, and Jameson SC. 2013. Transcriptional downregulation of S1pr1 is required for the establishment of resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol 14: 1285–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mackay LK, Braun A, Macleod BL, Collins N, Tebartz C, Bedoui S, Carbone FR, and Gebhardt T. 2015. Cutting edge: CD69 interference with sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor function regulates peripheral T cell retention. J Immunol 194: 2059–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crosby CM, and Kronenberg M. 2018. Tissue-specific functions of invariant natural killer T cells. Nat Rev Immunol 18: 559–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.