Abstract

Neutrophil influx and activation contributes to organ damage in several major lung diseases. This inflammatory influx is initiated and propagated by both classical chemokines such as interleukin-8 and by downstream mediators such as the collagen fragment cum neutrophil chemokine Pro-Gly-Pro (PGP), which share use of the ELR+ CXC receptor family. Benzyloxycarbonyl-proline-prolinal (ZPP) is known to suppress the PGP pathway via inhibition of prolyl endopeptidase (PE), the terminal enzyme in the generation of PGP from collagen. However, the structural homology of ZPP and PGP suggests that ZPP might also directly affect classical glutamate-leucine-arginine positive (ELR+) CXC chemokine signaling. In this investigation, we confirm that ZPP inhibits PE in vitro, demonstrate that ZPP inhibits both ELR+ CXC and PGP-mediated chemotaxis in human and murine neutrophils, abrogates neutrophil influx induced by murine intratracheal challenge with LPS, and attenuates human neutrophil chemotaxis to sputum samples of human subjects with cystic fibrosis. Cumulatively, these data demonstrate that ZPP has dual, complementary inhibitory effects upon neutrophil chemokine/matrikine signaling which make it an attractive compound for clinical study of neutrophil inhibition in conditions (such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) which evidence concurrent harmful increases of both chemokine and matrikine signaling.

Introduction

Neutrophils (PMNs) are an important component of the innate immune system. These immune system “first responders” are capable of phagocytosis of an invading pathogen, release of anti-microbial enzymes, and generation of an oxidative burst aimed at destroying a foreign organism (1). Unfortunately, this repertoire of potent antimicrobial components can also lead to indiscriminate damage of host tissue during the process of clearing an inflammatory stimulus. In a number of important lung diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis (CF), and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), PMN inflammation becomes chronic, leading to off-target extracellular matrix destruction and end-organ damage (2-5). When there is dysregulated neutrophilic inflammation and more severe or sustained tissue injury occurs, PMNs change from effectors of normal homeostasis to mediators of pathology (6).

PMN recruitment classically occurs through a PMN-specific chemokine family typified by interleukin-8 (IL-8). IL-8 is a glutamate-leucine-arginine positive (ELR+) CXC chemokine that acts via CXC chemokine receptors 1 and 2 (CXCR1 and CXCR2) in humans (5). There have been attempts to blunt the effect of IL-8 in a clinical setting using a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb), but with limited success (7). The limited efficacy of IL-8 inhibition might in part relate the presence of an IL-8- independent CXCR signaling pathway. It is now known that traditional ELR+ CXC chemokines are not the exclusive mechanism by which PMNs may be recruited via CXCR activation to sites of damage. A collagen breakdown fragment, proline-glycine-proline (PGP), which bears structural and sequence similarities to an important functional motif in the ELR+CXC chemokine family, is released from collagen in numerous chronic neutrophilic disorders (8-10). Indeed, in animal models and ex vivo studies, PGP appears to contribute to PMN influx and chemotaxis as much as classical ELR+ CXC chemokines IL-8 and MIP-2 (2, 4, 8, 11). PGP, and its more potent amino-terminal acetylated form (AcPGP), are products of a protease cascade initiated by matrix-metalloproteases (MMPs) acting upon collagen to form oligopeptides, which are cleaved by a serine protease, prolyl endopeptidase (PE) (8, 11). PE was originally described as a processor of neuropeptides in the central nervous system (12-14). More recently, it has been shown to play a key role outside the central nervous system. PE is the terminal enzyme in the generation of PGP from collagen, and has been shown to be active in a variety of chronic inflammatory lung diseases. All of the proteases necessary for PGP production, including PE, are found in PMNs and have been measured in clinical specimens from neutrophilic diseases (15, 16). Therefore, an initial PMN influx to collagen-rich tissues can be amplified by the generation of PGP in a feed-forward cycle. This PGP pathway therefore can operate independently of the classical ELR+ CXCR axis to sustain and/or propagate neutrophilic inflammation. Derangements of both the classical ELR+ CXCR pathway and PGP homeostasis have been linked to disease activity in COPD (8, 17, 18) and CF (19). Therefore, therapeutic strategies aimed at effectively abrogating CXCR signaling in chronic neutrophilic disorders may require diminution of both the ELR+ CXCR and PGP pathways.

Benzyloxycarbonyl-proline-prolinal (ZPP) was developed as a specific, noncompetitive inhibitor of PE (20-22), the terminal enzyme in PGP generation. In this report we describe and explain another property of ZPP, namely the inhibition of the receptor by which PGP and IL-8 exert biological activity on PMNs (CXCR1 and CXCR2). These dual inhibitory properties of ZPP may arise because of structural similarities between ZPP, PGP, and a binding pocket of CXCR1 and 2. We confirmed that ZPP is an effective inhibitor of PGP generation and were able to validate a potent, specific anti-CXCR effect of ZPP in vitro. We then validated potent inhibitory effects of ZPP on human PMN chemotaxis toward the sputum of subjects with cystic fibrosis, which is known to contain elevated levels of both PGP and IL-8. We conclude that ZPP offers a novel dual mechanism of PMN modulation with considerable therapeutic potential in diseases characterized by excessive PMN inflammation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All antibodies were purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Albumin from Bovine Serum, Cohn V Fraction was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Z-Gly-Pro-pNA was synthesized by Chem Impex International. DMEM was purchased from Mediatech. Z-Pro-Prolinal was obtained from CalBiochem (Gibbstown, NY) and Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

PE Activity Assay

100 ng PE was added to 1mM N-Succinyl-Gly-Pro-paranitroanilide (Suc-GP-pNA) in 100μL PBS with 10μM bovine serum albumin with or without ZPP and reaction permitted overnight at 4°C. Substrate cleavage was then measured by production of para-nitroanilide, read as absorbance at 410nm.

Electrospray ionization liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry for PGP detection

PGP and Ac-PGP were measured in all samples using an MDS Sciex (Applied Biosystems) API-4000 spectrometer equipped with a Shimadzu HPLC. HPLC was performed with a 2.1 × 150 mm Develosi C30 column (with buffer A: 0.1% formic acid and buffer B: acetonitrile plus 0.1% formic acid: 0-0.6 min 20% buffer B/80% buffer A, then increased over 0.6-5 min to 100% buffer B/0% buffer A. Background was then removed by flushing with 100% isopropanol plus 0.1% formic acid. Positive electrospray mass transitions were at 270-70 and 270-116 for PGP and 312-140 and 312-112 for Ac-PGP.

Neutrophil Chemotaxis Assays

The chemokine of interest was placed in the bottom chamber of a 96 well 3 μm filter plate from Millipore in a volume of 150μl Sputum samples were diluted 1:6 in DMEM for all assays. The filter was placed on top and 2 × 105 human or murine neutrophils were loaded on top in 100 μl of DMEM with 0.5% BSA. The plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 1 hour. The number of migrated cells were then determined using either photomicrographs taken with an Olympus IX70 or an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). ZPP inhibition of chemotaxis was determined by preincubating the cells with ZPP for 45 minutes at 20°C with agitation. Following this, a customary chemotaxis assay was performed.

Human neutrophil isolation

Whole blood was obtained from healthy volunteers by phlebotomy into heparinized vacuum phlebotomy vials. RBCs were allowed to sediment for 20 minutes at 20°C after 1:1 mixture with 5% dextran. Supernatant was eluted and centrifuged for 7 minutes at 1000xg at 20°C. Residual RBCs were lysed by resuspending the pellet in ice-cold 0.2% saline for 30 seconds then rapidly bringing solution to isotonicity with 1.6% saline. The cell pellet was resuspended in filter-sterilized 0.9% saline solution equal to starting volume of whole blood and 10mL of Ficoll gradient solution (GE Healthcare BioSciences) was layered at the bottom of a 50mL centrifuge tube. This was then centrifuged for 40 minutes at 1000xg at 4°C. The pellet, now consisting of purified peripheral blood PMNs, was then resuspended in 1mL filter-sterilized phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.5 without CaCl2/MgCl2) and set on ice. A 1:10 dilution in Trypan blue dye was performed and cells counted; viability of > 95% was confirmed for all experiments.

Murine neutrophil isolation

Mice were sacrificed, the femur and the tibia from both hind legs were removed and freed of soft tissue attachments, and the extreme distal tip of each extremity was amputated to expose the marrow. HBSS-EDTA solution was forced through the bone with a syringe. After dispersing cell clumps, the cell suspension was centrifuged (400xg, 10 min, 4°C) and resuspended in 1 ml PBS (pH 7.5 without CaCl2/MgCl2).

In vivo administration of LPS and ZPP

Balb/C mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor ME) were kept in the UAB Animal Research Facility. Food and water were given ad libitum. All experimental procedures were in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. LPS (10ng/mouse) was administered intratracheally in 50 μl of PBS. Mice were returned to the cage and sacrificed 24 hours later by intraperitoneal (IP) injection of .2ml Nembutal. ZPP was administered in 2% dioxane in PBS. ZPP was dosed at T-6, T=0 (this dose given in same aliquot as LPS), and T+6 hours, with mice sacrificed and bronchoalveolar lavage performed at T+12 hours.

Collection of mouse bronchalveolar lavage fluid

Mice were euthanized with IP injection of Nembutal. A 10 cc syringe connected to a three way stop-cock was attached to a 22 G flexible catheter. The catheter was inserted into the proximal end of the trachea and the lungs were slowly perfused with 3 × 1ml of PBS (room temperature). BAL was collected using an empty 10 cc syringe attached at the third spot on the stop-cock. Cell counts were determined using Trypan Blue staining and a hemocytometer. For further confirmation, cytospins were done of all samples and staining was performed using Trypan Blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

PGP generation from intact collagen using neutrophil lysates

4 × 106 neutrophils/ml were lysed using 2x freeze-thaw cycles in PBS with 10ng/ml Aprotinin (Sigma). 25μg Type I collagen, 25μg Type II collagen, with or without .25 mM ZPP, 150μl lysates, 10μM BSA, and 5μl 10mg/ml of bestatin (an inhibitor of the PGP-degrading enzyme leukotriene A4 hydrolase) was added every 6 hours. After 24 hours at 37°C, the samples were centrifuged, soluble fluid was recovered, washed on 10kDa Millipore filters (Billerica, MA) and analyzed on ESI-LC-MS/MS.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post-test were performed for comparison of 3 or more groups. Two-tailed student’s T-tests were used for simple significance testing. Means are presented as standard error of measurement with error bars representing same. Statistical significance was inferred for p values <0.05; p values are presented as: * <0.05, ** <0.01, *** <0.001, ****<0.0001.

Results

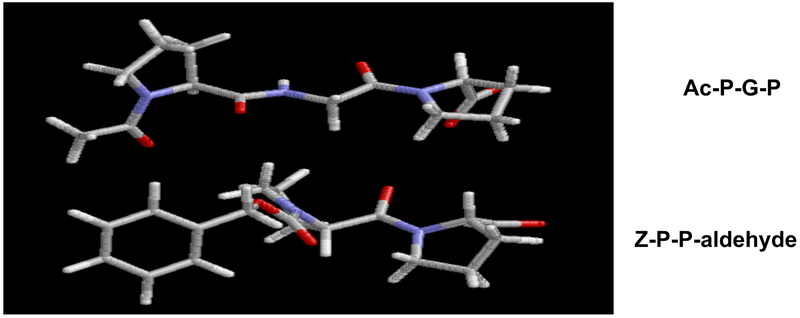

AcPGP and ZPP are structurally similar.

Computer modeling (Sybyl 7.0; Tripos, Inc.; Saint Louis, MO) of the neutrophil CXCR1 and 2 ligands Ac-PGP and the PE inhibitor ZPP demonstrated closely related structures (Fig 1). Both molecules have a ring structure at the amino-terminus with a proline at the carboxy-terminus. ZPP has a reactive aldehyde group on the C-terminus that forms a covalent bond with the serine in the catalytic triad of the active site of prolyl endopeptidase. The pronounced similarities between the molecules suggests structural orthology between an Ac-PGP binding pocket of CXCR1 and/or CXCR2 and the PE catalytic site which accommodates ZPP.

Fig. 1:

Three dimensional ball and stick structures of AcPGP and ZPP. Modeling was conducted with Sybyl 7.0 (Tripos, Inc.; Saint Louis, MO)

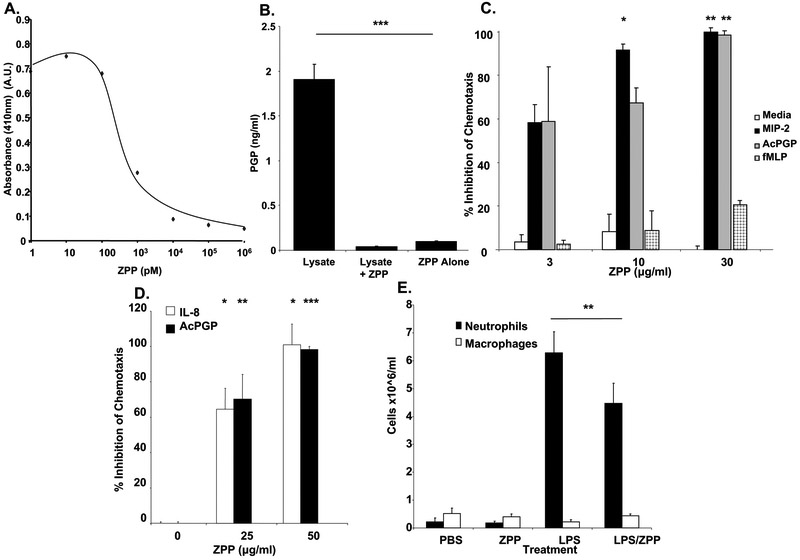

ZPP inhibits prolyl endopeptidase activity.

ZPP is known to be a potent PE inhibitor (20-22). We also performed an ex vivo assay utilizing neutrophil lysates and collagen to generate PGP (9). We repeated a dose curve of ZPP inhibiting PE activity using benzylocarbonyl pro-gly-paranitroanilide (ZGP-pNA), a PE substrate that generates para-nitroanilide upon cleavage. This confirmed that ZPP inhibits PE activity at nM concentrations (Fig 2A). We then performed an ex vivo assay to assess the relevance of this inhibition to PMN-induced PGP generation (9). Neutrophil lysates were incubated with intact Type I and Type II collagen and PGP generation was measured using electrospray ionization liquid chromatography mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (ESI-LC-MS/MS). We observed that PMN lysate is sufficient to produce PGP in the presence of intact collagen. In the presence of ZPP however, this ability to produce the chemotactic peptide was completely inhibited (Fig 2B). These findings confirm that ZPP effectively prevents the production of PGP by PMNs through its inhibition of PE, the only known enzyme capable of liberating PGP from collagen fragments.

Fig.2:

2A. ZPP dose dependently inhibits PE activity.

ZPP was preincubated with PE for five minutes at varying concentrations before the addition of ZGP-pNA and measured by absorbance at 410nm for production of para-nitroanilide.

2B. ZPP blocks PMN production of PGP from intact collagen.

Neutrophil lysates were incubated for 24 hours at 37°C with collagen with or without ZPP and the samples were passed through 10kDa filters and analyzed via ESI-LCMS/ MS.

2C. ZPP dose dependently and specifically inhibits ELR+CXC chemokine mediated mouse neutrophil chemotaxis. ZPP or vehicle was preincubated with murine neutrophils for 45 minutes at 4°C prior to use in a chemotaxis assay. MIP-2 (10ng/ml), AcPGP (100μg/ml), or fMLP (10μM), were placed in the bottom wells to incite PMN migration and the ratio of PMN migration between each condition and mean media control (chemotactic index) was calculated. Percentage inhibition was then quantified as: (1-[chemotactic index with inhibitor/chemotactic index without inhibitor])*100.

2D: ZPP dose dependently inhibits ELR+CXC chemokine mediated human neutrophil chemotaxis. In the same manner as the mouse, IL-8 (20ng/ml) and AcPGP (30μg/ml) driven chemotaxis was measured in presence or absence of ZPP.

2E. ZPP prevents LPS driven neutrophil migration in vivo. ZPP (100μg/animal) was instilled intra-tracheally (IT) into 8-10 week old female Balb/C mice at T=−6 hours, T=0, and T=6 hours, with 10ng of LPS administered IT at T=0. Animals were sacrificed, bronchoalveolar lavage performed, cells pelleted from fluid, stained and counted.

ZPP inhibits in vitro murine and human PMN chemotaxis to ELR+CXC chemokines.

ZPP effectively inhibited the generation of PGP from intact collagen ex vivo. Given its structural similarities to AcPGP, we next assessed whether ZPP modulates neutrophil chemotaxis. To investigate this we performed transwell chemotaxis assays with neutrophils in the presence or absence of ZPP and ELR+CXC chemokinetic ligands. ZPP completely inhibited murine and human neutrophil chemotaxis to ELR+CXC chemokines (MIP-2 and IL-8, respectively) in a dose-dependent manner, but did not affect chemotaxis to formyl-Methionine-Leucine-Phenylalanine (fMLP), another neutrophil chemoattractant that acts via a different receptor (Fig 2C, Fig 2D) (23, 24).

ZPP is active in an in vivo model of neutrophilic inflammation.

LPS (10ng) was instilled in the trachea of Balb/C mice (T=0 hours). LPS, a bacterial component, has been demonstrated to incite a rapid and robust neutrophil recruitment into the airways (25). Inhaled LPS is known to induce PMN influx into the lung via both ELR + CXC chemokine (26, 27) and AcPGP signaling (8). To measure the ability of ZPP to attenuate LPS-initiated pulmonary neutrophil influx, ZPP (100μg/dose) was given intra-tracheally to treatment and control groups of mice 6 hours prior to LPS administration, at time of LPS administration, and 6 hours after LPS dosing. At T=+12 hours, the mice were sacrificed and bronchoalveolar lavage was performed. Cells were pelleted and stained, then neutrophil and macrophage counts were determined and analyzed. LPS alone caused a >28-fold increase in the influx of neutrophils into the airways (Fig. 2E). However, when mice were pretreated with ZPP, there was a 30% decrease in the PMN burden.

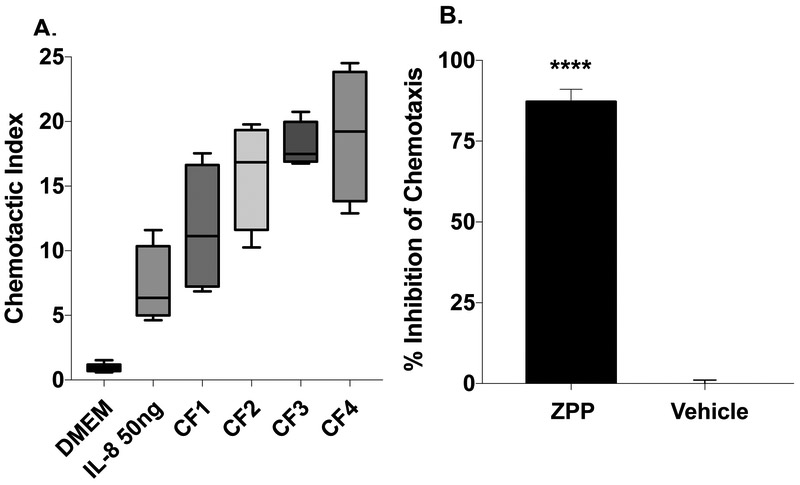

ZPP dose-dependently blocks neutrophil chemotaxis to CF sputum.

Sputum from cystic fibrosis patients contains high levels of the neutrophil chemoattractants IL-8 and PGP (3, 11, 28). Congruent with this, CF sputum is highly chemotactic to neutrophils ex vivo (29, 30). We utilized CF sputum as an ex vivo stimulus to study the potential effectiveness of ZPP as an inhibitor of a clinically significant source of neutrophil influx. IL-8 levels in the CF sputum tested were 2414 +/− 1308 pg/mL. All tested sputum samples were highly chemotactic to neutrophils (Fig. 3A). ZPP (100μg/mL), when preincubated with neutrophils, demonstrated inhibition of chemotaxis to sputum collected from CF patients. ZPP caused ~87% (Fig 3B) inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis. This near-complete neutralization is similar to that observed in the previous experiments with IL-8 and PGP and is all the more impressive considering the variety of neutrophil chemokines in CF sputum, including leukotriene B4 and fMLP present in CF sputum (31, 32). These data indicate that ZPP is effective not only against isolated neutrophil chemokines, but also in neutralization of PMN chemotaxis via disease specimens.

3A: ZPP dose dependently inhibits neutrophil chemotaxis to the sputum of n=4 cystic fibrosis patients. Chemotactic index was measured as in 2°C. for each sample and indexed to DMEM

3B: PMNs were preincubated at 20°C for 30minutes with either vehicle or ZPP prior to chemotaxis assay.

Discussion

The major finding of this work is that the compound ZPP is able to function in dual complementary roles as a neutrophil chemokine receptor antagonist by not only reducing the production of the CXCR1/2 ligand PGP but also through a direct inhibitory effect upon the receptor. Chronic neutrophilic inflammation is a hallmark of a number of major pulmonary diseases. The prolonged increase in proteolytic enzymes, and reactive oxygen species seen with persistent neutrophilia causes deleterious remodeling of the pulmonary extracellular matrix (ECM) (33, 34). In many of these disorders, a decline in lung function has been shown to correlate with the level of neutrophil influx, neutrophil chemokines, and neutrophil-derived proteases present in clinical samples from diseased patients (35-38). To our knowledge, this is the first known compound capable of acting as both an inhibitor of the generation of an inflammatory ligand and as an antagonist for that ligand’s receptor. As such, ZPP would seem to have significant therapeutic potential in chronic PMN-predominant inflammatory disorders in which excesses of PGP and IL-8 signaling co-occur (e.g., COPD and CF) (35).

Using the paradigm we describe here, the rational design of therapeutics that inhibit an enzyme that produces the receptor ligand and the receptor binding site itself allows for identification of single compounds with action upon multiple levels within a pathway. More specifically, our findings provide proof of principle for a potent suppression of pulmonary neutrophilic inflammation derived from the properties of ZPP upon multiple levels of ELR + CXCR signaling. This might be therapeutically useful in chronic neutrophilic disorders such as COPD and CF. Because of the structural similarities between the PE and CXC receptor ligands ZPP and AcPGP, respectively (Fig. 1), we suspect that the dual inhibitory activity of ZPP is due to similarity between the catalytic site of PE and the active site of CXCR1/2. Therefore, other inhibitors of PE might have CXCR-inhibitory activity analogous to that of ZPP. At least one known PE inhibitor is already in clinical use for other indications. Valproic acid (VPA) is a catalytic site inhibitor of PE with good bioavailability used to treat a variety of psychiatric conditions such as seizure disorders and bipolar disorder (39, 40). However, whether VPA inhibits CXCR remains untested.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that ZPP plays dual, complementary roles to effect potent inhibition of neutrophil influx in vitro and in vivo. This finding has therapeutic implications for disorders characterized by excessive neutrophilic inflammation in the lung and elsewhere. Also, we explore the intriguing concept of a single compound capable of blocking the generation of a neutrophil chemokine receptor ligand while also directly blocking the receptor itself. This concept could facilitate rational drug design for development of more potent agents to inhibit pathways for which multi-level blockade of feed-forward regulatory derangements are known to be advantageous, such as with the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Canonical and non-canonical CXCR signaling both contribute to PMN recruitment.

ZPP inhibits PE, reducing the production of the non-canonical CXCR ligand PGP.

ZPP also inhibits canonical (ELR+ CXC) CXCR signaling.

ZPP suppresses cystic fibrosis sputum-induced PMN chemotaxis via both mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by NIH/NHLBI: T32HL105346-07 to DWR, R35HL135710 to JEB, and R01HL126596 to JEB and AG; as well as the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research: Grant 017.008.029 to MAR

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nathan C Neutrophils and immunity: challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6: 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Reilly P, Jackson PL, Noerager B, Parker S, Dransfield M, Gaggar A, Blalock JE. N-alpha-PGP and PGP, potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets for COPD. Respir Res 2009; 10: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rowe SM, Jackson PL, Liu G, Hardison M, Livraghi A, Solomon GM, McQuaid DB, Noerager BD, Gaggar A, Clancy JP, O'Neal W, Sorscher EJ, Abraham E, Blalock JE. Potential role of high-mobility group box 1 in cystic fibrosis airway disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 178: 822–831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardison MT, Galin FS, Calderon CE, Djekic UV, Parker SB, Wille KM, Jackson PL, Oster RA, Young KR, Blalock JE, Gaggar A. The presence of a matrix-derived neutrophil chemoattractant in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. J Immunol 2009; 182: 4423–4431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizzarri C, Beccari AR, Bertini R, Cavicchia MR, Giorgini S, Allegretti M. ELR+CXC chemokines and their receptors (CXC chemokine receptor 1 and CXC chemokine receptor 2) as new therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther 2006; 112: 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makam M, Diaz D, Laval J, Gernez Y, Conrad CK, Dunn CE, Davies ZA, Moss RB, Herzenberg LA, Tirouvanziam R. Activation of critical, host-induced, metabolic and stress pathways marks neutrophil entry into cystic fibrosis lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 5779–5783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahler DA, Huang S, Tabrizi M, Bell GM. Efficacy and safety of a monoclonal antibody recognizing interleukin-8 in COPD: a pilot study. Chest 2004; 126: 926–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weathington NM, van Houwelingen AH, Noerager BD, Jackson PL, Kraneveld AD, Galin FS, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Blalock JE. A novel peptide CXCR ligand derived from extracellular matrix degradation during airway inflammation. Nat Med 2006; 12: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaggar A, Rowe SM, Matthew H, Blalock JE. Proline-Glycine-Proline (PGP) and High Mobility Group Box Protein-1 (HMGB1): Potential Mediators of Cystic Fibrosis Airway Inflammation. Open Respir Med J 2010; 4: 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaggar A, Weathington N. Bioactive extracellular matrix fragments in lung health and disease. J Clin Invest 2016; 126: 3176–3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaggar A, Jackson PL, Noerager BD, O'Reilly PJ, McQuaid DB, Rowe SM, Clancy JP, Blalock JE. A novel proteolytic cascade generates an extracellular matrix-derived chemoattractant in chronic neutrophilic inflammation. J Immunol 2008; 180: 5662–5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welches WR, Santos RA, Chappell MC, Brosnihan KB, Greene LJ, Ferrario CM. Evidence that prolyl endopeptidase participates in the processing of brain angiotensin. J Hypertens 1991; 9: 631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myohanen TT, Kaariainen TM, Jalkanen AJ, Piltonen M, Mannisto PT. Localization of prolyl oligopeptidase in the thalamic and cortical projection neurons: a retrograde neurotracing study in the rat brain. Neurosci Lett 2009; 450: 201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor WL, Dixon JE. Catabolism of neuropeptides by a brain proline endopeptidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1980; 94: 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaggar A, Li Y, Weathington N, Winkler M, Kong M, Jackson P, Blalock JE, Clancy JP. Matrix metalloprotease-9 dysregulation in lower airway secretions of cystic fibrosis patients. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007; 293: L96–L104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Reilly PJ, Hardison MT, Jackson PL, Xu X, Snelgrove RJ, Gaggar A, Galin FS, Blalock JE. Neutrophils contain prolyl endopeptidase and generate the chemotactic peptide, PGP, from collagen. J Neuroimmunol 2009; 217: 51–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Reilly PJ, Jackson PL, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Scanlon PD, Blalock JE. Sputum PGP is reduced by azithromycin treatment in patients with COPD and correlates with exacerbations. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e004140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells JM, O'Reilly PJ, Szul T, Sullivan DI, Handley G, Garrett C, McNicholas CM, Roda MA, Miller BE, Tal-Singer R, Gaggar A, Rennard SI, Jackson PL, Blalock JE. An aberrant leukotriene A4 hydrolase-proline-glycine-proline pathway in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190: 51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu X, Abdalla T, Bratcher PE, Jackson PL, Sabbatini G, Wells JM, Lou XY, Quinn R, Blalock JE, Clancy JP, Gaggar A. Doxycycline improves clinical outcomes during cystic fibrosis exacerbations. Eur Respir J 2017; 49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakker AV, Jung S, Spencer RW, Vinick FJ, Faraci WS. Slow tight-binding inhibition of prolyl endopeptidase by benzyloxycarbonyl-prolyl-prolinal. Biochem J 1990; 271: 559–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilk S, Orlowski M. Inhibition of rabbit brain prolyl endopeptidase by n-benzyloxycarbonyl-prolyl-prolinal, a transition state aldehyde inhibitor. J Neurochem 1983; 41: 69–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaszuba K, Rog T, St Pierre JF, Mannisto PT, Karttunen M, Bunker A. Molecular dynamics study of prolyl oligopeptidase with inhibitor in binding cavity. SAR QSAR Environ Res 2009; 20: 595–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmblad J, Malmsten CL, Uden AM, Radmark O, Engstedt L, Samuelsson B. Leukotriene B4 is a potent and stereospecific stimulator of neutrophil chemotaxis and adherence. Blood 1981; 58: 658–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zen K, Liu Y. Role of different protein tyrosine kinases in fMLP-induced neutrophil transmigration. Immunobiology 2008; 213: 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asti C, Ruggieri V, Porzio S, Chiusaroli R, Melillo G, Caselli GF. Lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice. I. Concomitant evaluation of inflammatory cells and haemorrhagic lung damage. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2000; 13: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Standiford TJ, Kunkel SL, Basha MA, Chensue SW, Lynch JP 3rd, Toews GB, Westwick J, Strieter RM. Interleukin-8 gene expression by a pulmonary epithelial cell line. A model for cytokine networks in the lung. J Clin Invest 1990; 86: 1945–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang S, Paulauskis JD, Godleski JJ, Kobzik L. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and KC mRNA in pulmonary inflammation. Am J Pathol 1992; 141: 981–988. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiron R, Grumbach YY, Quynh NV, Verriere V, Urbach V. Lipoxin A(4) and interleukin-8 levels in cystic fibrosis sputum after antibiotherapy. J Cyst Fibros 2008; 7: 463–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackerness KJ, Jenkins GR, Bush A, Jose PJ. Characterisation of the range of neutrophil stimulating mediators in cystic fibrosis sputum. Thorax 2008; 63: 614–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dudez TS, Chanson M, Schlegel-Haueter SE, Suter S. Characterization of a novel chemotactic factor for neutrophils in the bronchial secretions of patients with cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis 2002; 186: 774–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAllister F, Henry A, Kreindler JL, Dubin PJ, Ulrich L, Steele C, Finder JD, Pilewski JM, Carreno BM, Goldman SJ, Pirhonen J, Kolls JK. Role of IL-17A, IL-17F, and the IL-17 receptor in regulating growth-related oncogene-alpha and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in bronchial epithelium: implications for airway inflammation in cystic fibrosis. J Immunol 2005; 175: 404–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao S, Wright AK, Montiero W, Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Grigg J. Monocyte chemoattractant chemokines in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2009; 8: 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barnes PJ. Mechanisms in COPD: differences from asthma. Chest 2000; 117: 10S–14S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malerba M, Ricciardolo F, Radaeli A, Torregiani C, Ceriani L, Mori E, Bontempelli M, Tantucci C, Grassi V. Neutrophilic inflammation and IL-8 levels in induced sputum of alpha-1-antitrypsin PiMZ subjects. Thorax 2006; 61: 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell DW, Gaggar A, Solomon GM. Neutrophil Fates in Bronchiectasis and Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13 Suppl 2: S123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell DW, Wells JM, Blalock JE. Disease phenotyping in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the neutrophilic endotype. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2016; 22: 91–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gaggar A, Hector A, Bratcher PE, Mall MA, Griese M, Hartl D. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J 2011; 38: 721–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griese M, Kappler M, Gaggar A, Hartl D. Inhibition of airway proteases in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur Respir J 2008; 32: 783–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chateauvieux S, Morceau F, Dicato M, Diederich M. Molecular and therapeutic potential and toxicity of valproic acid. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abdul Roda M, Sadik M, Gaggar A, Hardison MT, Jablonsky MJ, Braber S, Blalock JE, Redegeld FA, Folkerts G, Jackson PL. Targeting prolyl endopeptidase with valproic acid as a potential modulator of neutrophilic inflammation. PLoS One 2014; 9: e97594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.