Abstract

Purpose

Among medical professionals, there appears to be a significant lack of knowledge about oocyte cryopreservation. Medical professionals may be potential candidates for elective oocyte cryopreservation due to the demands and commitments of medical training. There is a paucity of data on this topic among medical professionals. The aim of this study was to assess knowledge, understanding, and beliefs towards elective egg freezing among medical professionals to assess whether they are potential candidates for elective egg freezing.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional descriptive study in a university-based training program. All medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty were included. An online survey was emailed to potential participants. It included demographic questions regarding childbearing decision-making factors, fertility knowledge, and attitudes towards using elective oocyte cryopreservation.

Results

A total of 1000 emails were sent. Of those, 350 completed surveys were received. On average, 33% of responders provided a correct answer to each fertility knowledge question. The duration of training and the heavy workload with long duty hours were the most common influencing factors when deciding the timing of childbearing. Overall, 65% of the male and female responders were concerned about their future fertility. Among those women who had future fertility concerns, 8% were not aware of egg freezing as a fertility option and wished they had had an opportunity to freeze their eggs at an earlier time.

Conclusions

Physicians’ childbearing decisions can be affected by the demands of their careers. Elective oocyte cryopreservation could be considered an option for family planning. Educational sessions and awareness programs are needed to provide information about available fertility preservation options, which can potentially decrease the rate of regret.

Keywords: Elective egg freezing, Social egg freezing, Oocyte cryopreservation, Medical professionals

Purpose

The interest in oocyte cryopreservation (OC) for non-medically indicated reasons, known as elective egg freezing, is growing secondary to increasing awareness and social factors, especially with the announcement from the American Society of Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) that OC should no longer be considered experimental [1]. OC is a method of freezing oocytes in order to pause their biologic activity and preserve them for future use [1]. Prior studies have reported personal and social factors as reasons for pursuing elective egg freezing [2–13]. In an online cross-sectional survey designed by Lallemant et al. in Denmark and the UK, 89% of women who had heard of egg freezing considered it acceptable for social reasons, such as being single, age under 35 years, childlessness. De Groot et al. conducted a qualitative study in a Dutch university medical center and interviewed women who were on the waiting list for oocyte banking. These women opted for oocyte banking because they wished to share parenthood with a future partner rather than becoming single parents [5]. In a national cross-sectional electronic survey conducted in the USA, the majority of responders supported elective OC, and the most common indications were delayed childbearing for career development, lack of a partner, and financial constraints [12]. In a recent study, among educated professional women who had undertaken at least one cycle of elective egg freezing in the USA and Israel, 85% undertook elective egg freezing secondary to lack of a partner [14]. Inhorn MC et al., in another binational (the USA and Israel) analysis, reported that partnership problems, rather than career planning, lead most women on the pathway to elective egg freezing [15].

As mentioned earlier, multiple studies have been published about elective egg freezing globally; however, there has been limited research assessing beliefs among medical professionals towards elective egg freezing [16–18]. Not all of the previous studies included both genders [18]. Although females are the ones who undergo the procedure, their partners (mainly males, except for homosexual females) can play important roles in their childbearing decisions. Apart from single females, couples normally decide about family planning together, and females might rely on their partners’ support (financial, emotional, etc.). Hence, males were also enrolled in this study, and partner rationales were included in the questions as well.

One previous study included physicians from only one specialty, obstetrics and gynecology [16]. Finally, none of the prior studies enrolled physicians at different levels of training. The aim of this study was to assess knowledge, understanding, and beliefs towards elective egg freezing among medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty members in an academic institution and to assess whether they are potential candidates for elective egg freezing.

Methods

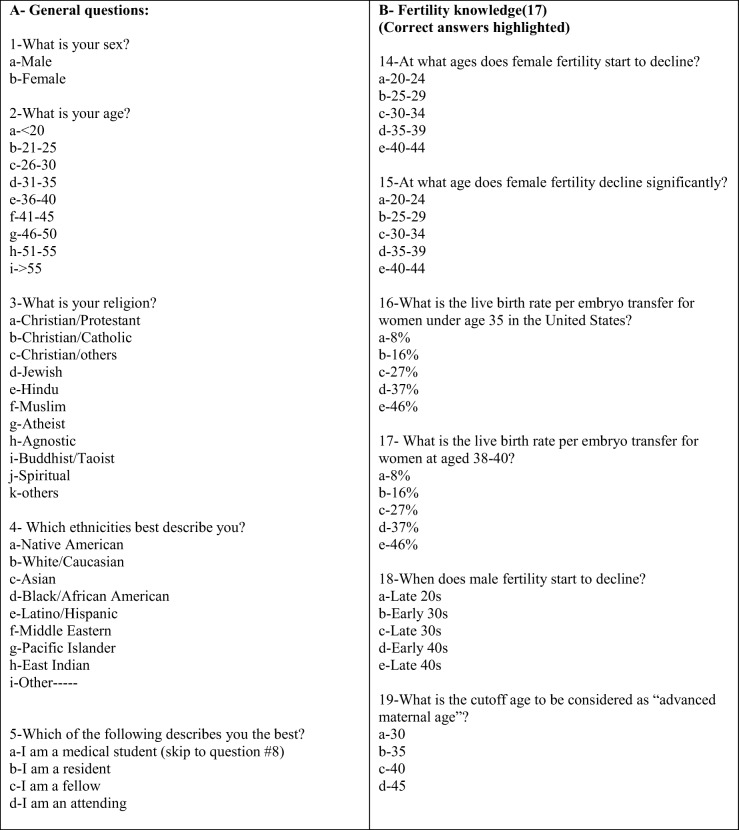

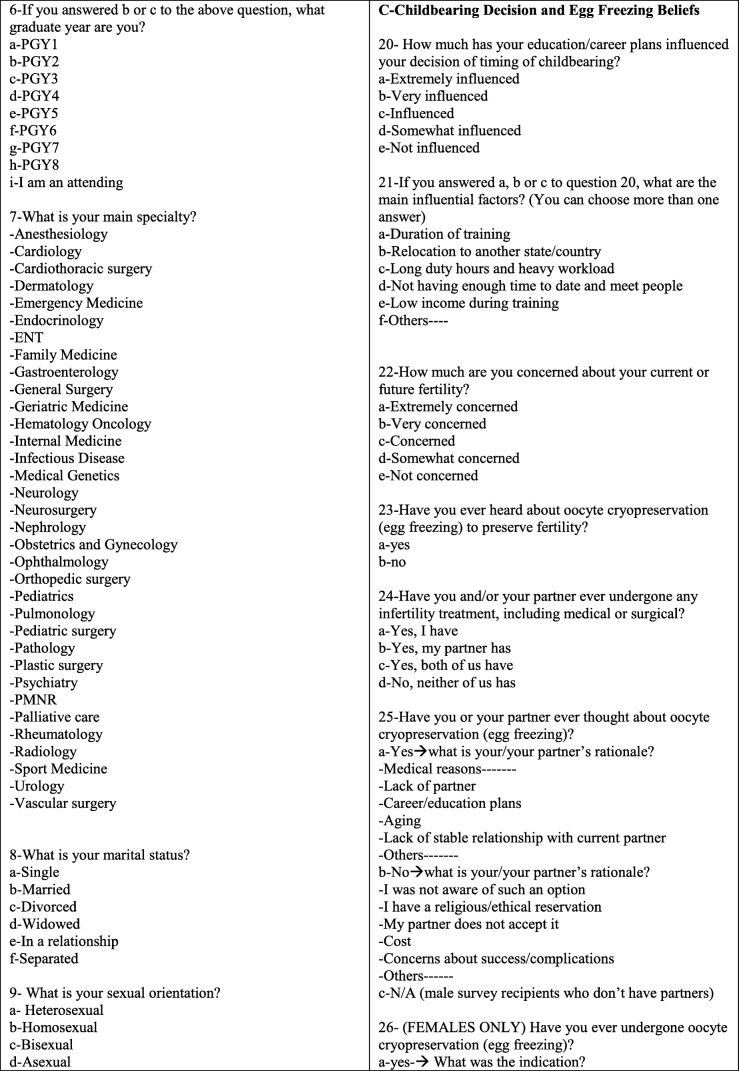

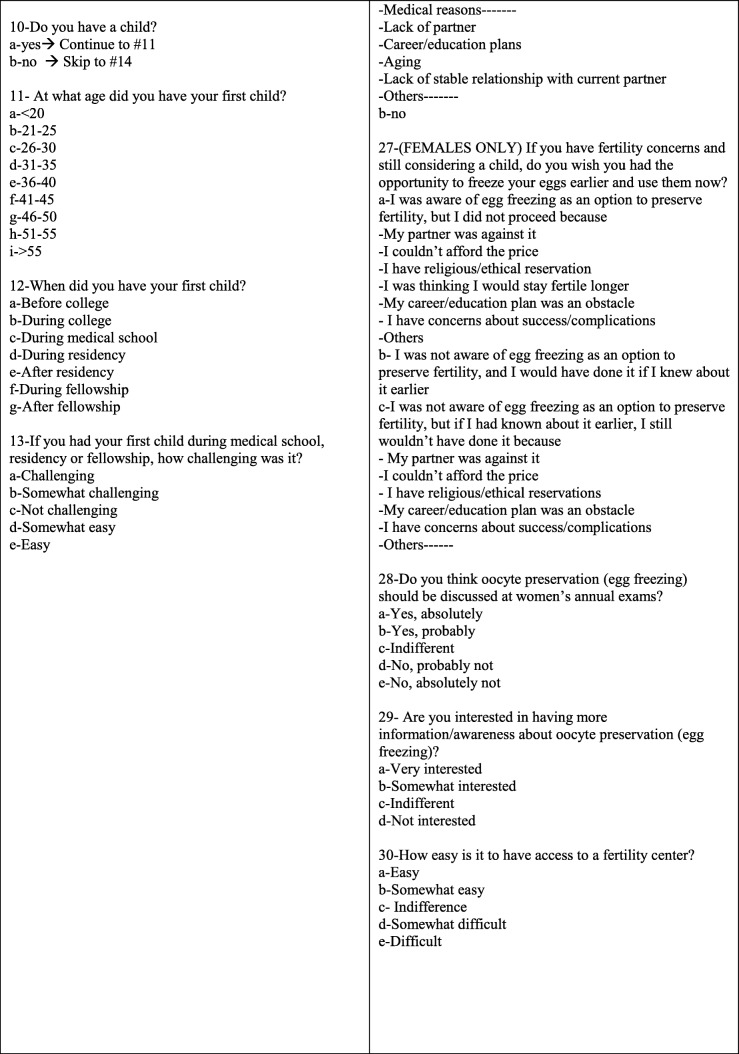

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study. A multidisciplinary team including expert senior faculty developed an anonymous online survey of 30 multiple-choice questions (Table 1). Topics and related questions were chosen on the basis of a literature review. Qualtrics survey software was used to design the questionnaire. The survey was emailed to all medical students, residents, fellows, and faculty members at McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston during the academic year of 2017–2018. The survey was emailed only once and was open for completion for 2 months. No reminder emails were sent out. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained for this study from the McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Informed consent was included on the welcome page of the survey.

Table 1.

Questionnaire

McGovern Medical School is the seventh largest medical school in the nation and has a similar curriculum and duration as most of the other national medical schools. The duration of graduate programs (i.e., residency and fellowship) varies depending on the specialty. Postgraduate year (PGY) is a numerical order used to stratify the grade and year of training after medical school.

The survey had three sections: demographics, fertility knowledge, and childbearing decision and egg freezing beliefs. In the demographic section, information regarding age, gender, marital status, parenthood status, sexual orientation, religion, level of training, and specialty were obtained. Both men and women were included in this study. The fertility knowledge questions [19] covered male and female age at fertility decline and the associated live birth rate per embryo transfer. In the last section, participants were questioned about their childbearing experiences and challenges during training. They were also questioned about their beliefs and interest in elective egg freezing.

Data were entered into an Excel sheet and analyzed using SPSS (Version 21). Descriptive statistics were used to analyze study characteristics. Chi-square test was used to analyze the group differences. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston has a total of 240 medical students, 1127 residents/fellows, and 1507 faculty members (total of 2874). However, since the email was sent through the general institutional email list, only 1000 emails were successfully sent because not everyone is listed in the general email pool. A total of 350 responses were received (35% response rate). Some of the questions were left unanswered by a few individuals. For example, some individuals preferred not to report their age, gender, specialty, etc. The majority were between 26 and 35 years of age (52%), Caucasian (54%), Christian (52%), married (53%), and childless (66%) (Tables 2 and 3). The response rate was almost equal across all levels (from medical student to the faculty level). Among those in training, the majority of the responses were obtained from PGY1 and PGY2 students (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic information

| Characteristics total respondents | N 350 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| -Female | 246 | 73 |

| -Male | 93 | 27 |

| -Total | 339 | 100 |

| Age | ||

| -21–25 | 61 | 18 |

| -26–30 | 106 | 31 |

| -31–35 | 72 | 21 |

| -36–40 | 42 | 12 |

| -41–45 | 17 | 5 |

| -46–50 | 13 | 4 |

| -51–55 | 6 | 2 |

| -> 55 | 19 | 7 |

| -Total | 336 | 100 |

| Religion | ||

| -Christian | 176 | 52 |

| -Jewish | 16 | 5 |

| -Hindu | 16 | 5 |

| -Muslim | 17 | 5 |

| -Atheist | 61 | 18 |

| -Buddhist | 5 | 1 |

| -Others | 25 | 7 |

| -Prefer not to answer | 24 | 7 |

| -Total | 340 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| -White | 184 | 54 |

| -Hispanic or Latino | 43 | 13 |

| -Black or African American | 27 | 8 |

| -Asian | 59 | 17 |

| -Native American or American Islander | 2 | 1 |

| -Others | 15 | 4 |

| -Prefer not to answer | 9 | 3 |

| -Total | 339 | 100 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| -Heterosexual | 312 | 93 |

| -Bisexual | 12 | 4 |

| -Homosexual | 5 | 1 |

| -Asexual | 1 | 0 |

| -Prefer not to answer | 5 | 1 |

| -Total | 335 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||

| -Single | 100 | 30 |

| -Married | 176 | 53 |

| -Divorced | 6 | 2 |

| -Widowed | 0 | 0 |

| -In a relationship | 43 | 13 |

| -Separated | 2 | 1 |

| -Prefer not to answer | 4 | 1 |

| -Total | 331 | 100 |

| Level of profession | ||

| -Medical student | 74 | 22.3 |

| -Resident | 113 | 34.1 |

| -Fellow | 49 | 14.8 |

| -Attending | 95 | 28.7 |

| -Total | 331 | 100 |

| Level of training (residents and fellows) | ||

| -PGY1 | 44 | 27 |

| -PGY2 | 32 | 20 |

| -PGY3 | 20 | 12 |

| -PGY4 | 24 | 15 |

| -PGY5 | 16 | 10 |

| -PGY6 | 17 | 10 |

| -PGY 7 | 6 | 4 |

| -Total | 159 | 100 |

Table 3.

Childbearing information. The most common answers are in italics

| -Do you have a child? | ||

| Choice | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| Yes | 117 | 35 |

| No | 218 | 65 |

| Total | 335 | 100 |

| -At what age did you have your first child? | ||

| Choice | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| < 21 years | 0 | 0 |

| 21–25 years | 6 | 5.4 |

| 26–30 years | 49 | 45 |

| 31–35 years | 38 | 35 |

| 36–40 years | 14 | 13 |

| 41–45 years | 3 | 3 |

| 46–50 years | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 110 | 100 |

| -When did you have your first child? | ||

| Choice | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| Before college | 0 | 0 |

| During college | 4 | 4 |

| During medical school | 15 | 14 |

| During residency | 39 | 36 |

| After residency | 10 | 9 |

| During fellowship | 17 | 16 |

| After fellowship | 22 | 21 |

The gender distribution at the University of Texas at Houston is almost equal, with a slightly higher rate of female medical professionals. However, 73% of responders were females.

The majority of responders for all training levels were females, except for 46- to 55-year-old individuals, and the gender distribution was equal in this age group. Regarding relationship status, there were more females than males in the married, single, and relationship groups (70%, 79%, and 66%, respectively), whereas in the divorced group, 60% of responders were males. One hundred percent of asexual and bisexual and 72% of heterosexual responders were females. However, equal gender distribution was noted among homosexual responders. Last, 77% of childless responders were females.

In the second part of the questionnaire, 5 questions were used to assess the knowledge about fertility reserve and ART. On average, 33% of responders provided the correct answer for each fertility knowledge question. Fifty-six percent answered correctly to questions testing knowledge about female fertility, 12% to questions on male fertility, and 21% to ART questions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Fertility knowledge. Correct answers are in italics

| Total | 107 | 100 |

|---|---|---|

| -At what age does female fertility start to decline? | ||

| Age | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| 20–24 years | 3 | 1 |

| 25–29 years | 36 | 11 |

| 30–34 years | 185 | 58 |

| 35–39 years | 95 | 30 |

| 40–44 years | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 320 | 100 |

| -At what age does female fertility decline significantly? | ||

| Age | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| 20–24 years | 0 | 0 |

| 25–29 years | 0 | 0 |

| 30–34 years | 15 | 5 |

| 35–39 years | 172 | 54 |

| 40–44 years | 132 | 41 |

| Total | 319 | 100 |

| -What is the live birth rate per embryo transfer for women under age 35 in the United States? | ||

| Live birth rate | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| 8% | 10 | 3 |

| 16% | 59 | 19 |

| 27% | 96 | 30 |

| 37% | 90 | 29 |

| 46% | 59 | 19 |

| Total | 314 | 100 |

| -What is the live birth rate per embryo transfer for women aged 38–40? | ||

| Live birth rate | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| 8% | 114 | 36 |

| 16% | 100 | 32 |

| 27% | 73 | 23 |

| 37% | 26 | 8 |

| 46% | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 315 | 100 |

| -When does male fertility start to decline? | ||

| Age | Answers (N) | Percentage (%) |

| Late 20s | 1 | 0 |

| Early 30s | 10 | 3 |

| Late 30s | 37 | 12 |

| Early 40s | 93 | 30 |

| Late 40s | 176 | 55 |

| Total | 317 | 100 |

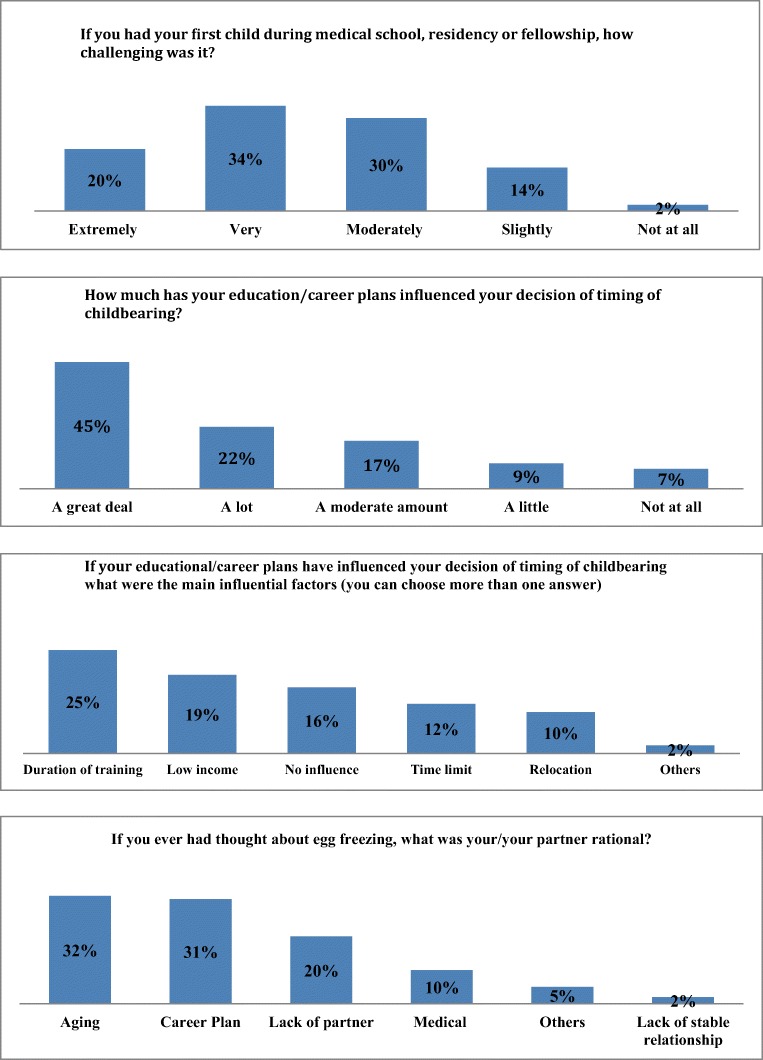

The third part of the questionnaire evaluated childbearing challenges and assessed the level of concern regarding future fertility. In general, the decision about the timing of childbearing was challenging for the majority (84%) of medical professionals (Fig. 1). The duration of training and heavy workload with long work hours were the most common influencing factors for deciding the timing of childbearing, with 30% reporting having thoughts at least once in the past about elective egg freezing due to either age (31%) or duration of training (30%). Overall, 65% of all female and male responders were concerned about their future fertility. Among those women who were concerned about their future fertility, 8% expressed regret for not pursuing oocyte cryopreservation in the past due to lack of knowledge. These women would have considered OC earlier if they knew they had this option for fertility preservation (Table 1, question 27-b).

Fig. 1.

Childbearing challenges

Demographic information, fertility knowledge, future fertility concern, and the rate of regret were analyzed and compared between groups: parents versus childless respondents (Table 5). The parent group was the individuals who answered “yes” to question number 10 (Table 1). Overall, 66% of the medical professionals in all levels of training were childless. Significant differences between the parent and childless groups (P value < 0.05) were as follows: there were more females and males in the childless group compared with the parent group (68% and 55%, respectively). As expected, the childless group was significantly younger than the parent group (21–30 years vs. 31–45 years). The majority (73%) of the childless individuals were medical students and residents, whereas the parent group was composed of mainly (77%) fellows and faculty. Finally, the childless group was mostly unmarried, in contrast to the parent group (66% vs 13%, respectively). There was no significant difference in sexual orientation. On average, compared with the responders who had children, childless responders had less knowledge about ART and male fertility and more knowledge about female fertility. The differences in answers were statistically significant in questions number 17, 18, and 19 (Table 1), P value < 0.05 (Table 5). Only the childless group expressed regret about not proceeding with oocyte cryopreservation in the past due to lack of knowledge compared with the parent group; however, this finding was not statistically significant.

Table 5.

Study results based on parenthood status

| Parent N = 117 |

Childless N = 219 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender | 0.016 | ||

| Female | 76 (65) | 169 (77) | |

| Male | 41 (35) | 50 (23) | |

| Total | 117 (100) | 219 (100) | |

| Age (years) | < 0.001 | ||

| -21–25 | 3 (3) | 60 (27) | |

| -26–30 | 13 (11) | 92 (42) | |

| -31–35 | 34 (29) | 40 (18) | |

| -36–40 | 25 (21) | 16 (7) | |

| -41–45 | 13 (11) | 4 (2) | |

| -46–50 | 9 (8) | 2 (1) | |

| -51–55 | 5 (4) | 1 (0.5) | |

| -> 55 | 15 (13) | 4 (2) | |

| -Total | 117 (100) | 219 (100) | |

| Level of training | < 0.001 | ||

| -Medical student | 3 (3) | 72 (33) | |

| -Resident | 22 (20) | 89 (40) | |

| -Fellow | 25 (23) | 23 (11) | |

| -Faculty | 59 (54) | 34 (16) | |

| -Total | 109 (100) | 218 (100) | |

| Relationship status | < 0.001 | ||

| -Married | 101 (87) | 75 (34) | |

| -Single | 3 (2.5) | 97 (45) | |

| -Separated | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| -Divorced | 4 (3.5) | 2 (1) | |

| -In a relationship | 3 (2.5) | 41 (19) | |

| -Prefer not to answer | 3 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | |

| -Total | 116 (100) | 216 (100) | |

| Sexual orientations | 0.084 | ||

| -Heterosexual | 114 (97) | 199 (91) | |

| -Homosexual | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | |

| -Bisexual | 1 (1) | 11 (5) | |

| -Asexual | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | |

| -Prefer not to answer | 2 (2) | 3 (1.5) | |

| -Total | 117 (100) | 219 (100) | |

| Average rate of correct answers to questions about | |||

| -ART | 30% | 24% | |

| Q-16 | 0.292 | ||

| Q-17 | < 0.001 | ||

| -Female fertility | 61% | 65% | |

| Q-14 | 0.885 | ||

| Q-15 | 0.145 | ||

| Q-19 | < 0.001 | ||

| -Male fertility | 17% | 9% | 0.029 |

| Q-18 | |||

| Fertility concern | < 0.001 | ||

| -Extremely concerned | 3 (2.5) | 24 (12) | |

| -Very concerned | 4 (3.5) | 28 (13) | |

| -Moderately concerned | 21 (19) | 60 (29) | |

| -Slightly concerned | 19 (17) | 49 (23) | |

| -Not concerned at all | 65 (58) | 48 (23) | |

| -Total | 112 (100) | 209 (100) | |

| Concerned women | 0.183 | ||

| -Aware of options and still did not proceed | 35 (85) | 95 (82) | |

| -Not aware of options and would not proceed if they had known earlier | 6 (15) | 12 (11) | |

| -Not aware and wished had known earlier (regret rate) | 0 (0) | 8 (7) | |

| -Total | 41 (100) | 115 (100) | |

Similar information was analyzed in five groups based on their level of concern about future fertility (Table 6). As expected, the childless group expressed significantly more concern regarding future fertility compared with the parent group, P value < 0.05. Moreover, 88% of the responders who rated their concern as “very concerned” or “extremely concerned” were childless (Table 6). Overall, those females and males who were concerned about their future fertility had greater knowledge about ART and female fertility than those who were not concerned at all. The regret rate was 25% among women who were extremely concerned about their future fertility and 8% in women who were not concerned at all.

Table 6.

Study results based on future fertility concern

| Characteristics N (%) |

Extremely concerned N = 28 |

Very concerned N = 33 |

Moderately concerned N = 79 |

Slightly concerned N = 68 |

Not concerned N = 114 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | < 0.001 | |||||

| Female | 26 (93) | 28 (85) | 67 (85) | 50 (76) | 59 (52) | |

| Male | 2 (7) | 5 (15) | 12 (15) | 16 (24) | 55 (48) | |

| Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 79 (100) | 67 (100) | 114 (100) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| -21–25 | 2 (7) | 10 (30) | 17 (21) | 20 (29) | 11 (10) | |

| -26–30 | 7 (25) | 12 (37) | 31 (39) | 21 (31) | 26 (23) | |

| -31–35 | 12 (43) | 8 (24) | 21 (27) | 21 (31) | 14 (12) | |

| -36–40 | 5 (18) | 2 (6) | 8 (10) | 5 (7) | 19 (17) | |

| -41–45 | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 14 (12) | |

| -46–50 | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (8) | |

| -51–55 | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | |

| -> 55 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 16 (14) | |

| -Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 79 (100) | 68 (100) | 114 (100) | |

| Level of training | < 0.001 | |||||

| -Medical student | 2 (7) | 10 (30) | 19 (24) | 25 (37) | 17 (15) | |

| -Resident | 11 (40) | 14 (43) | 12 (15.5) | 20 (30) | 26 (24) | |

| -Fellow | 7 (25) | 3 (9) | 35 (45) | 15 (22) | 11 (10) | |

| -Faculty | 8 (28) | 6 (18) | 12 (15.5) | 7 (11) | 57 (51) | |

| -Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 78 (100) | 67 (100) | 111 (100) | |

| Relationship status | 0.109 | |||||

| -Married | 11 (40) | 14 (43) | 36 (48) | 37 (54) | 66 (58) | |

| -Single | 10 (35) | 12 (36) | 26 (35) | 25 (37) | 26 (23) | |

| -Separated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| -Divorced | 2 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.5) | |

| -In a relationship | 5 (18) | 7 (21) | 11 (15) | 6 (9) | 12 (11) | |

| -Prefer not to answer | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.5) | |

| -Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 76 (100) | 68 (100) | 113 (100) | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.118 | |||||

| -Heterosexual | 26 (93) | 32 (97) | 78 (99) | 62 (91) | 102 (89) | |

| -Homosexual | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |

| -Bisexual | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (9) | 5 (4) | |

| -Asexual | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| -Prefer not to answer | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |

| -Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 79 (100) | 68 (100) | 114 (100) | |

| Childbearing status | < 0.001 | |||||

| -Parent | 3 (11) | 4 (12) | 20 (25) | 20 (29) | 49 (43) | |

| -Childless | 25 (89) | 29 (88) | 59 (75) | 48 (71) | 65 (57) | |

| -Total | 28 (100) | 33 (100) | 79 (100) | 68 (100) | 114 (100) | |

| Average rate of correct answers to questions about | ||||||

| -ART | 20% | 11% | 15% | 20% | 14% | < 0.001 |

| Q-16 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Q-17 | 0.434 | |||||

| -Female fertility | 72% | 60% | 65% | 54% | 57% | < 0.001 |

| Q-14 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Q-15 | ||||||

| Q-19 | ||||||

| -Male fertility | 11% | 9% | 5% | 12% | 16% | 0.001 |

| Q-18 | ||||||

| Concerned women | 0.014 | |||||

| -Aware of options and still did not proceed | 17 (71) | 20 (95) | 46 (90) | 30 (86) | 16 (67) | |

| -Not aware of options and would not proceed if they had known earlier | 1 (4) | 1 (5) | 3 (6) | 3 (8) | 6 (25) | |

| -Not aware and wished had known earlier (regret rate) | 6 (25) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (6) | 2 (8) | |

| -Total | 24 (100) | 21 (100) | 51 (100) | 35 (100) | 24 (100) |

Discussion

Physicians and medical professionals are potential candidates for elective OC due to the demands of a career in medicine, including long work hours, years spent in training, and relocation constraints. In our study, the duration of training and heavy workload with long work hours were the most common influencing factors for deciding the timing of childbearing among medical professionals.

This raises questions regarding whether medical professionals and the general population have correct and up-to-date information and resources pertaining to assisted reproductive technology and its indications. Multiple studies have identified a lack of knowledge about female fertility and current reproductive procedures among the general population and around the globe [20–22]. In a recent survey among only obstetrics and gynecology residents in the USA, half of the residents overestimated the age at which female fertility markedly declines, and over 78% of residents overestimated the likelihood of success using assisted reproductive technology [16].

Forty-one percent of participants incorrectly answered the age at which female fertility declines significantly. This shows the false perception and knowledge of important female fertility information among medical professionals who desire future fertility. Moreover, the majority of the responders, 81%, thought that the “live birth rate per embryo transfer for women under age 35” is less than 46%; the most common wrong answer was 27% (the correct answer is 46%, Table 1) [19]. In other words, responders underestimated the OC success rate. Finally, our study showed that the childless responders had less knowledge about ART and male infertility, emphasizing the importance of education. Education on fertility preservation options such as OC, as well as explaining ART risks, benefits, and success rates, could help medical professionals in their family planning.

According to the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and ASRM, there is not yet sufficient data to recommend OC for the sole purpose of circumventing reproductive aging in healthy women; however, reproductive-aged women seeking OC as a fertility preservation option need to understand and receive appropriate counseling regarding the benefits, limitations, and risks of elective OC. Both organizations emphasize the importance of pretreatment counseling [1, 23].

Although OC is a promising method for fertility preservation, there are limited data for elective OC, as much of the existing data are from donor populations and infertile couples with supernumerary oocytes [1]. In addition, the majority of the websites on the social media do not follow the Society of Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART)/ASRM guidelines, which could provide inaccurate information to those candidates who consider OC at some point in their lives [24].

Finally, the cost of egg freezing is another challenge; it is an expensive process and might be financially prohibitive for individuals and couples considering the treatment [25].

This study has several strengths and limitations. Given that it was conducted at one academic institution, our conclusions may not be generalizable to institutions in other regions. Physicians in academic centers may have longer work hours and more obligations (i.e., research, administrative, teaching) with less work hour flexibility compared with community programs or private practice physicians. Since not all recipients responded to the survey, the results may have been influenced by selection bias. Moreover, geographical factors such as culture, race, religion, and fertility rate could also each add a selection bias as well.

This survey was an online survey with no direct interaction with participants. A face-to-face interview may be more effective in conveying accurate perceptions, beliefs, and interests regarding OC. Furthermore, this survey has not been validated previously. Responders might have not interpreted the questions in the same way as they were intended.

To the best of our knowledge, the authors are not aware of any studies evaluating medical professionals’ beliefs, knowledge, and rate of regret regarding elective egg freezing across all specialties in academic centers in the USA. Only two prior studies have assessed elective egg freezing knowledge among medical professionals; these included either medical students [18] or obstetrics/gynecology residents in the USA, and did not capture other specialties [16]. Greenwood et al. studied the degree of decision regret following elective egg freezing; however, minimal data exist on the regret of not choosing OC at an earlier age, specifically among medical professionals [26]. Moreover, this study included male and female participants from various levels of training from medical students to fellows and attending physicians. Although the gender distribution in the study population is almost equal, only 27% of responders were males. We may interpret this to mean that males were not interested in this subject. Another explanation could be that females are more concerned about their future fertility than males (as we showed in our study); hence, they are more interested in participating in such surveys. Given the low male response rate, the authors emphasize the importance of fertility preservation awareness among medical professionals of both genders.

Although some responders had children and were married, some participants may not have had the time due to the constraints of medical training. The commitment and demands of medical training should not be a deterrent to family planning. As we showed in the “Results” section, the majority of the individuals who were concerned about their future fertility were childless, and sadly, the childless female group had the highest rate of regret. As we showed in our results, the majority of the childless responders were concerned about future fertility. Given that a large number of medical professionals were childless (66% across all levels of training), awareness, education, support, and resource provision could be considered helpful to address their concerns. Medical professionals are a population that may delay childbearing until training is complete (the parent group in our study included mainly fellows and faculty), and having more knowledge about the process of OC may help decrease the risk of regret. While we currently have the opportunity to use technology, science, and fertility specialists to help individuals reach this important goal, medical professionals might need to implement the available technology for themselves. Teaching and awareness becomes priceless. Because trainees might have time limitations in obtaining routine annual checkups or well-woman exams, educational programs such as free webinars, grand rounds, educational pamphlets, and inviting guest speakers to talk about fertility and reproductive options could be helpful additions to a training program’s extracurricular activities/events. Workplace culture and work conditions also play an important role in childbearing decisions. Making workplaces more comfortable for medical professionals, especially for pregnant individuals or nursing mothers, could positively help them to have children during their most fertile years. Allowing pumping breaks, providing nursing rooms, providing access to daycare facility at the workplace, or dividing in-house calls into shorter intervals, etc. could be reasonable strategies. We also suggest adding a questionnaire as a part of a wellness program in assessing trainees’ fertility knowledge in addition to providing resources for providers in the area.

Conclusions

Physicians’ childbearing decisions can be influenced by the demands of their careers. Among medical professionals across all levels of training, genders, and various specialties, there seems to be a lack of knowledge about egg freezing as a fertility preservation option. Many medical professionals have challenges in terms of childbearing during training and have future fertility concerns. Elective oocyte cryopreservation could be considered an option for family planning. Educational sessions and awareness programs are needed to provide information about available fertility preservation options, which could potentially decrease the rate of regret.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Susan Nasab, Phone: 713-500-6412, Email: susan.hosseininasab@uth.tmc.edu.

Kemi Nurudeen, Phone: 713-796-1434.

Mazen E. Abdallah, Phone: 713-796-1434

References

- 1.Practice Committees of American Society for Reproductive M, Society for Assisted Reproductive T. Mature oocyte cryopreservation: a guideline. Fertil Steril 2013,99:37–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Lallemant C, Vassard D, Nyboe Andersen A, Schmidt L, Macklon N. Medical and social egg freezing: internet-based survey of knowledge and attitudes among women in Denmark and the UK. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1402–1410. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wennberg AL, Rodriguez-Wallberg KA, Milsom I, Brannstrom M. Attitudes towards new assisted reproductive technologies in Sweden: a survey in women 30-39 years of age. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:38–44. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniluk JC, Koert E. Childless women’s beliefs and knowledge about oocyte freezing for social and medical reasons. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2313–2320. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Groot M, Dancet E, Repping S, Goddijn M, Stoop D, van der Veen F, Gerrits T. Perceptions of oocyte banking from women intending to circumvent age-related fertility decline. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1396–1401. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoop D, Nekkebroeck J, Devroey P. A survey on the intentions and attitudes towards oocyte cryopreservation for non-medical reasons among women of reproductive age. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:655–661. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baldwin K, Culley L, Hudson N, Mitchell H, Lavery S. Oocyte cryopreservation for social reasons: demographic profile and disposal intentions of UK users. Reprod BioMed Online. 2015;31:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu KE, Greenblatt EM. Oocyte cryopreservation in Canada: a survey of Canadian ART clinics. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:250–256. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, Pritchard N, Hickey M, Peate M, McBain J, Agresta F, Bayly C, Fisher J. Reproductive experiences of women who cryopreserved oocytes for non-medical reasons. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:575–581. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natasha Pritchard MK, Hammarberg K, McBain J, Agresta F, Bayly C, Hickey M, Peate M, Fisher J. Characteristics and circumstances of women in Australia who cryopreserved their oocytes for non-medical indications. J Reprod Infant Psyc. 2017;35(2):108–118. doi: 10.1080/02646838.2016.1275533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodes-Wertz B, Druckenmiller S, Smith M, Noyes N. What do reproductive-age women who undergo oocyte cryopreservation think about the process as a means to preserve fertility? Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis EI, Missmer SA, Farland LV, Ginsburg ES. Public support in the United States for elective oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2016;106:1183–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vallejo V, Lee J, Schuman L, Witkin G, Cervantes E, Sandler B, Copperman A. Social and psychological assessment of women undergoing elective oocyte cryopreservation: a 7-year analysis. Open J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;3:1–7. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2013.31001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inhorn MC, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Birger J, Westphal LM, Doyle J, Gleicher N, Meirow D, Dirnfeld M, Seidman D, Kahane A, Patrizio P. Elective egg freezing and its underlying socio-demography: a binational analysis with global implications. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2018;16:70. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0389-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inhorn MC, Birenbaum-Carmeli D, Westphal LM, Doyle J, Gleicher N, Meirow D, Dirnfeld M, Seidman D, Kahane A, Patrizio P. Ten pathways to elective egg freezing: a binational analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:2003–2011. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1277-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Peterson B, Inhorn MC, Boehm JK, Patrizio P. Knowledge, attitudes, and intentions toward fertility awareness and oocyte cryopreservation among obstetrics and gynecology resident physicians. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:403–411. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O-027 Is egg freezing for social reasons a good idea? S. Gorth; C. Wright eaWywrtHRi.

- 18.Tan SQ, Tan AW, Lau MS, Tan HH, Nadarajah S. Social oocyte freezing: a survey among Singaporean female medical students. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2014;40:1345–1352. doi: 10.1111/jog.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marc A. Fritz LS, Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility 8th edition, Chapter 27, P 1140–1147.

- 20.Adashi EY, Cohen J, Hamberger L, Jones HW, Jr, de Kretser DM, Lunenfeld B, et al. Public perception on infertility and its treatment: an international survey. The Bertarelli Foundation scientific board. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:330–334. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daniluk JC, Koert E, Cheung A. Childless women’s knowledge of fertility and assisted human reproduction: identifying the gaps. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blake D, Smith D, Bargiacchi A, France M, Gudex G. Fertility awareness in women attending a fertility clinic. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;37:350–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1997.tb02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.ACOG (2014) CONoc, Obstet Gynecol, 123 (1), 221–222. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Avraham S, Machtinger R, Cahan T, Sokolov A, Racowsky C, Seidman DS. What is the quality of information on social oocyte cryopreservation provided by websites of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology member fertility clinics? Fertil Steril. 2014;101:222–226. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirshfeld-Cytron J, Grobman WA, Milad MP. Fertility preservation for social indications: a cost-based decision analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:665–670. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwood EA, Pasch LA, Hastie J, Cedars MI, Huddleston HG. To freeze or not to freeze: decision regret and satisfaction following elective oocyte cryopreservation. Fertil Steril. 2018;109:1097–1104 e1091. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]