Abstract

This article provides an overview of the principles in the evaluation and management of perianal Crohn's disease (CD). Manifestation-specific treatment is addressed including abscess, fistula, skin tags, hemorrhoids, fissure, ulcers, strictures, ano-, and rectovaginal fistulas as well CD-associated hidradenitis suppurativa.

Keywords: perianal, Crohn's disease, evaluation, management, abscess, fistula

Perianal fistulas and abscesses are common manifestations of Crohn's disease (CD), with an incidence that ranges from 18 to 43%. 1 They contribute to significant morbidity, including scarring, persistent drainage, abscess formation, fecal incontinence, and pain. Achieving complete fistula healing is commonly a laborious process involving multiple medical and surgical treatments. Interventions are followed by frequent relapses producing stress, coping difficulties, anxiety/depression, and fatigue. Worsening inflammation, decreased in quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization are common sequelae.

Patients with distal colonic or rectal disease involvement are at higher risk of developing perineal disease versus isolated ileal disease. Only 12% of patients with isolated ileal disease develop a perianal fistula compared with 92% of patients with rectal involvement. On the other hand, 5% of individuals will have isolated perianal disease without any evidence of luminal inflammation. 2 In a population-based study, perineal disease was present at or before time of diagnosis in 45% of cases; 55% were found at median of 4.8 years after diagnosis. 3 These findings highlight the difficulty in diagnoses of CD in patients who present only with perineal manifestations. Patients with perianal fistula are more likely to have extraintestinal manifestations of their inflammatory bowel disease including arthritis, oral ulcerations, and/or skin manifestations. They have a fivefold increased risk of developing a luminal fistula and a twofold increased risk of requiring surgery. 1 Optimal management of perianal CD requires an in-depth understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease, accurate diagnoses of the perineal process, and a multidisciplinary approach.

Initial Assessment and Diagnosis

CD can masquerade as other common anorectal pathology and often presents as the first manifestation of the disease. Perianal CD precedes intestinal symptoms in up to 45% of patients with a median of 4.5 years. 4 A substantial number of patients without CD can suffer from numerous anorectal pathologies including perineal abscesses, fistulas, fissures, hemorrhoids, and skin tags particularly in those who have chronic diarrhea. The overlap between CD and common anorectal pathology complicates achieving a precise and early diagnosis.

An accurate diagnosis of the perianal process allows the medical team to apply evidence-based care. Diagnosis requires a detailed history and physical examination, imaging, clinical evaluation, and assessment of luminal disease. Multiple studies have reported 100 accuracy in delineating the extend of the perianal process, using a combination of an examination under anesthesia, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis with intravenous contrast, and/or endorectal ultrasound to delineate. 5

MRI of the pelvis has become the gold standard for establishing the anatomy of complex abscesses and fistula. It identifies both the primary fistula and secondary extensions. Concomitant inflammatory and fibrotic processes commonly coexist. These additional factors make a strictly clinical assessment quite challenging. MRI is an invaluable tool to assess the pretreatment perineal process as well as in monitoring the response to treatment.

Evaluation of potential perianal CD without an established diagnosis of systemic disease requires clinical acumen and a high index of suspicion. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBD) may develop forma ordinaire anal fistula as well any common anorectal pathology. Clinicians should be able to recognize those with features of perianal CD on physical diagnosis especially in the absence of known IBD. Complex and recurrent abscesses as well as fistula originating above the dentate line without previous surgery are important examples. Other distinctive features of Crohn's perianal disease are illustrated in Figs. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 to 9 .

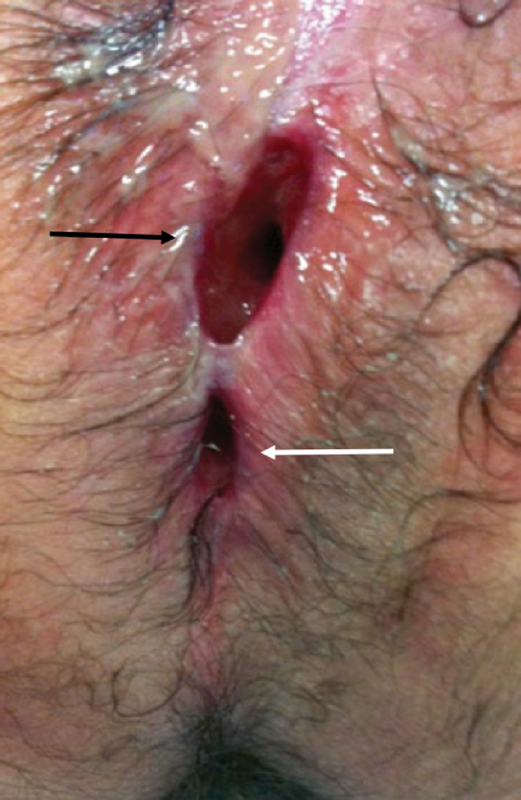

Fig. 1.

A nonhealing wound (black arrow) above the anus (white arrow) is evident months following incision and drainage of a perirectal abscess. This observation should raise concerns for perianal Crohn's disease (Photo—M. Valente).

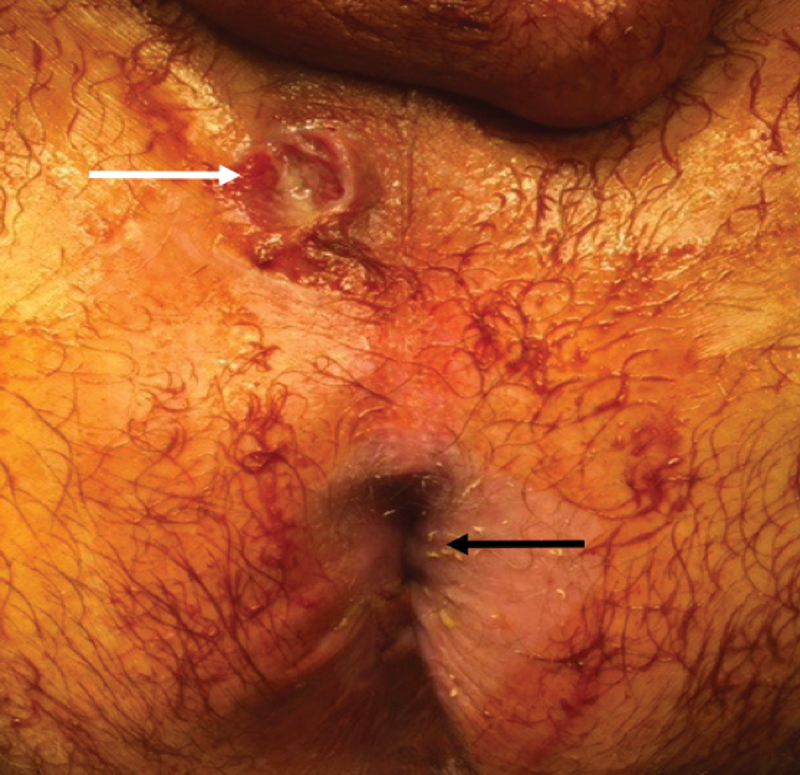

Fig. 2.

Multiple external openings of multiple fistulas are present (white arrow) surrounded by erythema and induration (black arrow). Investigation for enteric Crohn's disease is warranted (Photo—A. Ortega).

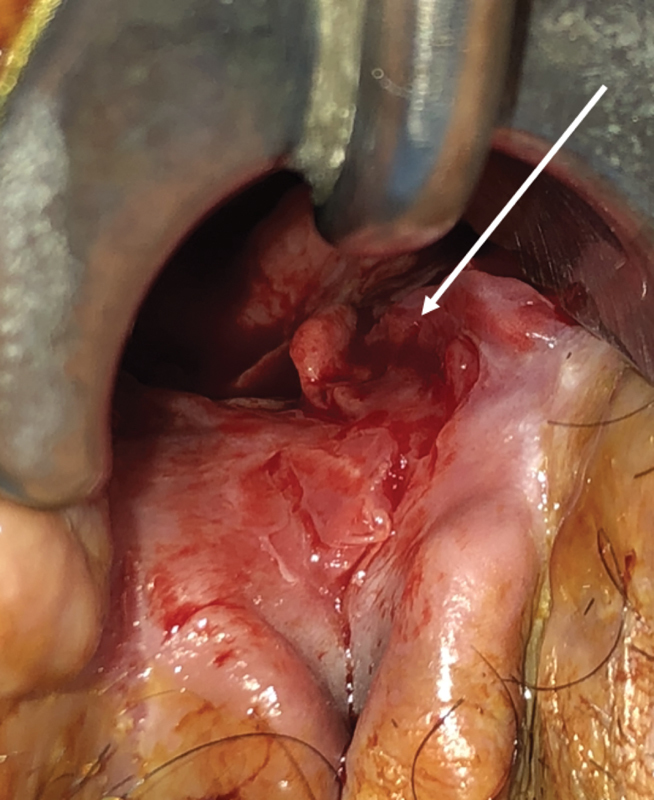

Fig. 3.

A wide-mouthed anal fistula (white arrow) is evident anterior to the anus (black arrow)—a characteristic finding in perianal Crohn's disease (Photo—J. Salgado, G. Salgado).

Fig. 4.

Proctitis (arrow) in the setting of an anal fistula is almost pathognomonic of perianal Crohn's disease (Photo—J. Salgado, G. Salgado).

Fig. 5.

( A ) Edematous skin tags with surrounding erythema are typical findings in perianal Crohn's disease. ( B ) Elephant skin tags are also highly suggestive (Photos—M. Valente).

Fig. 6.

Discrete patches of vitiligo admixed within dermal scarring are evident in a patient with perianal Crohn's disease (Photo—A. Ortega).

Fig. 7.

Scarring and deformity are commonly seen in perianal Crohn's disease. The anal orifice is obscured. Concern for neoplasm is also appropriate (Photo—A. Ortega).

Fig. 8.

The arrow points to a painless perianal ulcer associated with Crohn's disease (Photo—M. Valente).

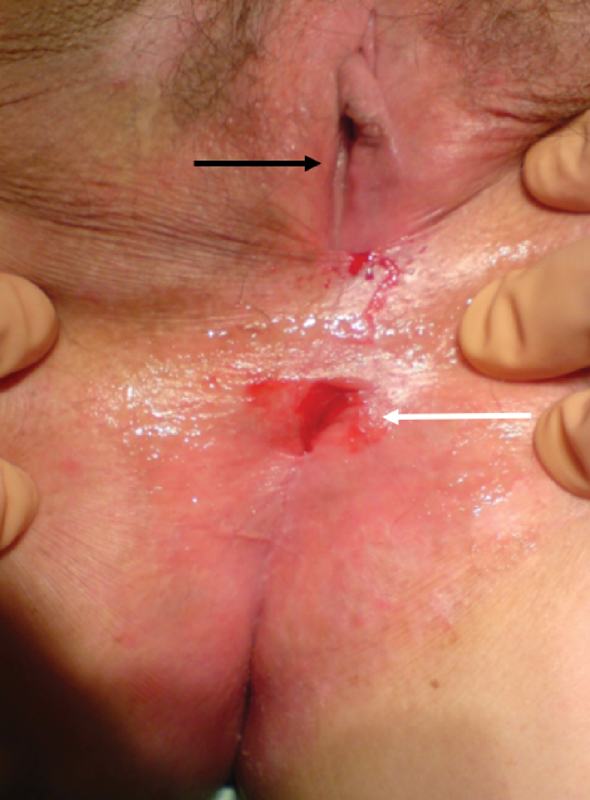

Fig. 9.

Anal stenosis (white arrow) is evident below the vaginal introitus (black arrow). In the absence of previous hemorrhoid surgery, congenital deformities, or a history of sexually transmitted diseases, this finding is highly suggestive of a perianal Crohn's disease (Photo—J. Salgado, G. Salgado).

It is important to consider and exclude other conditions that may have similar macroscopic perineal characteristics. The differential diagnoses include sexuality transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, hidradenitis suppurativa, anal carcinoma, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, and hematological conditions such as leukemia, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, as well as cryptoglandular complex anal fistulas.

A biopsy of perianal tissue has a low sensitivity and specificity to achieve histopathological diagnoses of CD. Typical granulomatous lesions are only seen in approximately one-third of the cases. 6 Curettage or biopsy of the tract is important to exclude neoplastic etiologies. It is often impossible to make a clinical diagnosis of perianal CD in the absence of intestinal disease. In this scenario, clinicians are advised to consider it as possible or probable perianal CD and proceed conservatively.

Management Principles

The goals of therapy are to achieve complete fistula closure and avoid some of the frequent complications that can lead to poor outcomes as well as negatively affect a patient's quality of life. Three factors have been shown to be independently predictive of a disabling CD course in the 5-year period following diagnosis: (1) the initial requirement for steroids, (2) an age at diagnosis below 40 years, and (3) the presence of perianal disease at diagnosis. 7

It is a generally agreed that measures aimed at providing long-term symptomatic treatment improve the prognosis. Patients satisfaction can be improved and achieved without complete healing. Two main global therapeutic strategies have been developed for the treatment of CD. Step-up strategy consists in adjusting the level of anti-inflammatory therapy to the anatomic and clinical severity of the disease. Top-down strategy emphasizes early intensive therapy.

Important factors operant in the management of perianal CD include:

Severity of the clinical manifestations

The impact on the patient's quality of life

Presence and/or extent of luminal enteric disease

Degree of proctitis

Response to the medical and surgical treatment

Poor prognostic factors include:

Persistent anal pathology

Rectal involvement

Complex fistulas

Rectovaginal fistulas

Deep cavitating ulcers

Strictures

Major incontinence

Progressive disease refractory to medical and surgical treatment including the need for proximal fecal diversion. 9

Most patients with the perianal CD pursue a benign course. 10 Many lesions heal spontaneously with effective management of the intestinal disease. Aggressive surgical intervention in the asymptomatic patients is unwarranted and can lead to increased postoperative morbidity greater the primary disease. Surgical intervention may be necessary for acute and chronic complications. The goal is to resolve the problem with as little damage to the anus and surrounding tissues. This minimalistic approach is often the best bridge to definitive treatment. 9

Manifestation-Specific Treatment

Abscess

Perianal abscess and fistula are the most common manifestation of perianal CD with an incidence of up to 43%. 10 Abscesses are complications of the primary cavitating lesions or cryptoglandular infections. Control of the sepsis by early drainage of the abscess is the only universally accepted option. It should be performed under anesthesia to adequately evaluate the abscess. Minimizing local trauma helps avoid nonhealing perianal/perineal wounds.

Placement of a mushroom or Pezzer catheter should be considered in large perianal and most ischioanal abscesses. This practice should ensure adequate drainage and minimize the early recurrence of the undrained fluid collections. The catheter is removed in 7 to 10 days if the drainage has stopped and the cavity has closed around it. 11

Probing should be done with extreme caution during the acute inflammatory process to prevent the creation of false tracks. The internal os is identifiable in less than 50% of the cases. 12

Purulent discharge per rectum is a fortuitous finding. It represents two possible scenarios. First is the internal rupture of an abscess with a supralevator component. Second is the localization of the primary opening of the fistulous component of the abscess. Placement of a draining seton is ideal in the latter case. This technique should diminish recurrences and/or progression of the disease locally.

The diagnosis of an intersphincteric abscess should be strongly considered when there is pain out of proportion to the external physical examination findings. Treating intersphincteric abscesses by dividing the internal sphincter muscle along the length of the abscess cavity should be avoided in the presence of active proctitis. Catheter drainage is a better alternative method in these patients.

Supralevator abscesses are confirmed by the palpation of a boggy fullness within the rectum. It is important to determine its origin. They can arise from a downward extension of a pelvic abscess as a result of enteric or colonic CD's involvement, or from an upward extension of an intersphincteric or ischioanal abscess. Misunderstanding of its origin and trajectory can lead to iatrogenic extrasphincteric or suprasphincteric fistulas.

Recurrence is frequently seen in almost 50% of the patients after the primary procedure. 13 Persistent pain and local inflammatory changes after drainage represent incomplete drainage. Reassessment with a pelvic MRI and repeated exam under anesthesia (EUA) is recommended. Gram-negative and anaerobic spectrum antibiotics are required adjunctively in immunocompromised individuals. They may also be considered in those with locally advanced sepsis or signs of systemic toxicity.

Fistulas

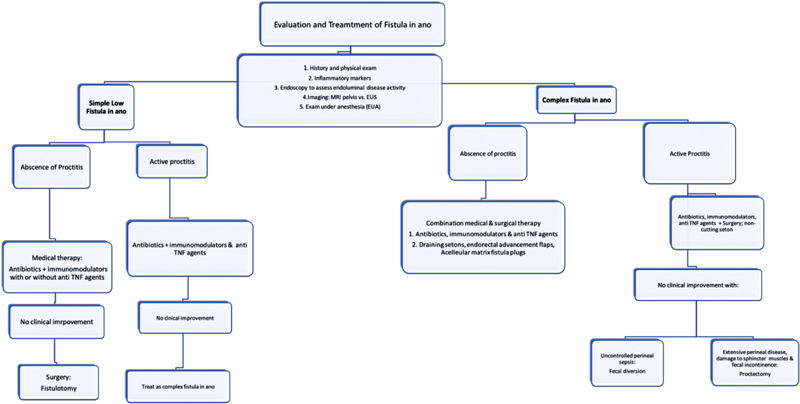

A simple low fistula is defined as a superficial, intersphincteric, or low transsphincteric track with a single external opening in the absence of proctitis. In patients without proctitis, the treatment consists of medical therapy with a trial of antibiotics and immunomodulators, with or without anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α))agents. These fistulas are usually asymptomatic. Surgical treatment is not obligatory due to the fact that healing rates with medical therapy alone are acceptable. Persistent suppuration without clinical improvement is an indication for a combined medical and surgical approach. Fistulotomy is the procedure of choice with good healing rates and minimal risk of incontinence in this setting. 14

Anti-TNF antibody in combination with surgery is preferable in the context of simple fistula and active proctitis. Fistulotomy imparts a higher incidence of nonhealing wounds and fecal incontinence. Noncutting setons are the preferred surgical option.

Complex fistula in ano are defined as those associated with

Multiple external openings

Atypical locations

Eccentric internal openings

Significant sphincteric involvement (i.e., high transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric trajectories)

Associated with a perianal abscess

Connecting to an adjacent structure (the vagina or bladder)

Horseshoe configuration

Treatment goals focus upon quality of life improvement and the avoidance of proctectomy. Control of the perineal sepsis by drainage of any underlying abscess is key. Noncutting (draining) setons are used in combination with different medical strategies. The medical armamentarium includes antibiotics, azathioprine/6-mecaptopurine, anti-TNF-α therapy (infliximab, adalimumab), or other biological agents. This approach can achieve a complete or partial healing in 68% of the cases. 15

Draining setons are removed between the second and third doses of a biologic agent. Both subjective and objective improvement should be in evidence. Inflammatory markers, MRI of the pelvis, and flexible sigmoidoscopy are useful documentation of disease regression/remission. Caution should be taken not to remove the setons too early. Abscess recurrence can occur in up to 30% due to the early closure of the external opening without healing the fistula track in this setting. 16

Endorectal advancement flap is part of the armamentarium for the treatment of complex fistulas without proctitis. A 60% of success rate is reported in different series. Recurrence and flap failure rates tend to be high with an incidence as high as 57%. The presence of concomitant small bowel disease is a predictor of poor outcome. 17

Acellular matrix fistula plugs and stem cell-based therapy are promising treatments. There are early reported success rates of 71%. 18

Fecal diversion may improve symptoms and assist in healing rates in patients with uncontrolled perineal sepsis. Recurrences are common and frequent intestinal continuity cannot be restored. Proctectomy with a permanent stoma is indicated in patients with extensive perineal disease with damage to the sphincter muscles causing fecal incontinence. Fig. 10 presents the authors' algorithm for the treatment of CD fistulas.

Fig. 10.

Evaluation and treatment of fistula in ano.

Anal Skin Tags

Anal skin tags are present in up to 70% of patients with perianal CD. They can become large, edematous, hard, and occasionally painful to minor local trauma. Difficult personal hygiene can be bothersome. They can interfere sexual activities. Resection is advised only in the absence of active proctitis due to the risk of nonhealing perianal wounds and sepsis. 19

Hemorrhoids

CD is not an absolute contraindication for hemorrhoidectomy in the absence of active proctitis. Caution and careful patient selection are recommended to avoid nonhealing of perianal wounds. One study from St. Marks Hospital reported ∼30% of their CD patients treated for hemorrhoids required a proctectomy for complications. 20 Rubber band ligation can be performed in selected surgical candidates in whom rectal inflammation is excluded and normal bowel habits are present.

Fissures

Anal fissures are a common finding in perianal CD. They often have an eccentric location and can be multiple. These fissures are usually painless and can heal spontaneously. Chronic induration and anal stenosis can occur upon healing. Posterior midline fissure can be quite painful as a result of internal sphincter hypertonicity and underlying sepsis or ulceration. First-line therapy includes nitroglycerin, diltiazem, botulinum toxin, and local steroids. Partial lateral internal sphincterotomy should be reserved only for those patients with highly symptomatic fissures associated with internal sphincter muscle hypertonicity, refractory to conservative measures and if diarrhea and rectal inflammation are not present.

Perianal Ulcers

Perineal ulcers result from the progression of local disease. Erosion may occur into the anal canal, sphincter muscles, perianal tissues, or the rectal wall. Their sequelae include sepsis and fibrostenotic strictures. Perianal ulcers present as painful lesions and up to 40% of those patients have active anal, rectal, or colonic luminal disease. 21 These lesions are associated with frequent complications that lead to poor outcomes and negatively affect a patient's quality of life. Medical treatment including antibiotics, immunomodulators, and biological agents should be individualized to each case. 22

Intensive local wound care including serial debridements, dressing changes, negative pressure wound vacuum therapy, and hyperbaric oxygen are valid alternatives in medical refractory lesions. Lesions refractory to all aforementioned therapies may require fecal diversion, proctectomy, or proctocolectomy with permanent end ileostomy.

Anorectal Strictures

Chronic diarrhea can provoke functional anal stenosis which should be differentiated from fibrostenotic strictures. Digital rectal examination helps distinguish between both entities. There are typically located at the level of the anorectal ring. Anal stenosis results from the healing process following perianal sepsis, complex fistulas, and deep ulcers. They are classified based upon the degree of luminal narrowing as mild, moderate, or severe.

Mild anal strictures are usually asymptomatic and do not require further treatment. Moderate or severe anal strictures can cause obstructive symptoms, urgency, or overflow incontinence. The therapeutic armamentarium is principally serial digital or instrumental dilation.

CD strictures can occur anywhere in the rectum and have been reported up to 5 to 13% of all patients with anorectal CD. 23 Long-standing and long-segment strictures should be biopsied to rule out invasive carcinoma. They are often asymptomatic and can remain quiescent for years. Fecal diversion is successful in controlling obstruction, urgency, and incontinence. Proctectomy with intersphincteric perineal resection is recommended in the presence of severe anal CD and symptomatic rectal stenosis. 24

Rectovaginal and anovaginal Fistulas

Rectovaginal fistulas are classified based on size, location, and etiology. Fistulas with a rectal opening at the dentate line and the vaginal OS just inside the vaginal fourchette are defined as low fistulas. High fistulas have a vaginal opening at or near the cervix or at the top of the remnant vagina following a hysterectomy. Middle fistulas are located between high and low fistulas. This classification is useful to plan the surgical approach. High fistulas are more likely to require a transabdominal approach. Perineal approaches are appropriate for most low and middle fistulas.

Rectovaginal fistulae have been reported in up to 10% in women with CD. 25 Management of this condition can be problematic. They are treated similar to complex fistulae using a combination of medical therapy with immunomodulators and an anti-TNF agent plus surgery. Anovaginal and mid-rectal vaginal fistulas are first approached via transperineal techniques in the absence of active proctitis. Multiple studies have reported healing rates in up to 75% of patients undergoing endorectal advancement flaps when adequate patient selection is performed. 26 Transvaginal advancement flap with or without an interposition tissue flap using bulbocavernosus muscle is a valid option especially with recurrent disease following previous failed endorectal flaps. Some authors advocate performing temporary fecal diversion in conjunction with the local flaps.

The role of noncutting seton placement is limited in the treatment of these fistulas due to the short track. It may increase the size of the openings and enlarge the track. An exception is the placement of a noncutting seton initially to control perianal sepsis. Despite optimal local repairs, many patients will require a proctectomy with permanent fecal diversion.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa Associated with CD

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition caused by follicular occlusion and secondary infection of apocrine sweets glands. It can be seen in association with other inflammatory conditions particularly with CD, although a definitive link between the two conditions has never been proven. 27

HS presents with pain, erythema, and swelling of the affected area. The natural history includes spontaneous resolution of painful subcutaneous nodules or progression to an abscess and chronic suppuration. Recurrent abscess with sinus tracks form are not connected to the rectum and do not penetrate the anal sphincters. Chronic fibrosis (pit like scars) frequently affects the perianal region. Differential diagnoses include pilonidal disease, cryptoglandular perianal fistulas, actinomycosis, and perianal CD.

Patients who present with cellulitis and no definite abscess can be treated with antibiotics which cover the skin flora. Recent studies have demonstrated a short-term clinical response ranging from 60 to 80% to biological agents such as infliximab and adalimumab. 28

Surgical treatment varies from simple incisions and drainage of undrained fluid collections to wide excision of all affected skin including all chronically scared tissues. A lower rate of recurrence could be archived with more radical resections. After surgical resection of the affected area, the resulting wounds can be closed primarily with sutures, skin graft or allowing it to heal by secondary intention. Fecal diversion may be necessary to improve symptoms in situations refractory to medical and/or surgical treatment.

Conclusions

A multidisciplinary team approach should be used for the assessment and treatment of perineal CD, including the tight collaboration of gastroenterologists, radiologists, and colorectal surgeons with the main objective to achieve maximum relief of symptoms and improve the quality of life.

Perineal CD can present with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Patients with mild symptomatology usually do not require surgical therapy even in the presence of persistence disease.

Medical therapy should be aggressively instituted early in patients with concomitant enteric disease.

To avoid devastating complications and minimize perioperative morbidity, such as perineal sepsis and chronic nonhealing wounds, surgeons should be cautious with the extent of the procedures and have a full understanding of the physio pathogenesis of the disease as well as of the perineal and pelvic anatomy. Finally, patients with uncontrolled symptoms with poor quality of life, refractory to medical and surgical treatment, with severe proctitis, may require fecal diversion and/or proctectomy.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Rankin G B, Watts H D, Melnyk C S, Kelley M L., JrNational Cooperative Crohn's Disease Study: extraintestinal manifestations and perianal complications Gastroenterology 197977(4 Pt 2):914–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz D A, Ghazi L J, Regueiro M. Guidelines for medical treatment of Crohn's perianal fistulas: critical evaluation of therapeutic trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(04):737–752. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz D, Loftus E, Tremaine W, Ranaccione R, Sandborn W J. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease: a population based study. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32 01:A18. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKee R F, Keenan R A. Perianal Crohn's disease--is it all bad news? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(02):136–142. doi: 10.1007/BF02068066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz D A, Wiersema M J, Dudiak K M et al. A comparison of endoscopic ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and exam under anesthesia for evaluation of Crohn's perianal fistulas. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(05):1064–1072. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.28676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hughes L E. Surgical pathology and management of anorectal Crohn's disease. J R Soc Med. 1978;71(09):644–651. doi: 10.1177/014107687807100904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre J P, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(03):650–656. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keighley M R, Allan R N. Current status and influence of operation on perianal Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1(02):104–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01648416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh B, McC Mortensen N J, Jewell D P, George B. Perianal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2004;91(07):801–814. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz D A, Pemberton J H, Sandborn W J. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(10):906–918. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-10-200111200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fry R D, Shemesh E I, Kodner I J, Timmcke A. Techniques and results in the management of anal and perianal Crohn's disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168(01):42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pearl R K, Andrews J R, Orsay C Pet al. Role of the seton in the management of anorectal fistulas Dis Colon Rectum 19933606573–577., discussion 577–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritchard T J, Schoetz D J, Jr, Roberts P L, Murray J J, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Perirectal abscess in Crohn's disease. Drainage and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33(11):933–937. doi: 10.1007/BF02139102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Church J M. Biological immunomodulators improve the healing rate in surgically treated perianal Crohn's fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(10):1217–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sands B E, Anderson F H, Bernstein C N et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(09):876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rasul I, Wilson S R, MacRae H, Irwin S, Greenberg G R. Clinical and radiological responses after infliximab treatment for perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(01):82–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joo J S, Weiss E G, Nogueras J J, Wexner S D. Endorectal advancement flap in perianal Crohn's disease. Am Surg. 1998;64(02):147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia-Olmo D, Herrero D, Pascual I et al. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula: a phase II clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(01):79–86. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181973487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sandborn W J, Fazio V W, Feagan B G, Hanauer S B; American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee.AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease Gastroenterology 2003125051508–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffery P J, Parks A G, Ritchie J K.Treatment of haemorrhoids in patients with inflammatory bowel disease Lancet 19771(8021):1084–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michelassi F, Melis M, Rubin M, Hurst R D. Surgical treatment of anorectal complications in Crohn's disease. Surgery. 2000;128(04):597–603. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho E Y, Katz J A, Comineli F. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. Medical management of Crohn's disease; pp. 213–215. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams N S, Macfie J, Celestin L R. Anorectal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1979;66(10):743–748. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800661018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linares L, Moreira L F, Andrews H, Allan R N, Alexander-Williams J, Keighley M R. Natural history and treatment of anorectal strictures complicating Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1988;75(07):653–655. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radcliffe A G, Ritchie J K, Hawley P R, Lennard-Jones J E, Northover J M. Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31(02):94–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02562636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodner I J, Mazor A, Shemesh E I, Fry R D, Fleshman J W, Birnbaum E H.Endorectal advancement flap repair of rectovaginal and other complicated anorectal fistulas Surgery 199311404682–689., discussion 689–690 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ostlere L S, Langtry J A, Mortimer P S, Staughton R C. Hidradenitis suppurativa in Crohn's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125(04):384–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb14178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Rappard D C, Limpens J, Mekkes J R. The off-label treatment of severe hidradenitis suppurativa with TNF-α inhibitors: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2013;24(05):392–404. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2012.674193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]