Abstract

Busulfan conditioning is utilized for hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) depletion in the context of HSC gene-therapy conditioning but may result in insufficient immunosuppression. In this study, we evaluated whether additional immunosuppression is required for efficient engraftment of gene-modified cells using a rhesus HSC lentiviral gene-therapy model. We transduced half of rhesus CD34+ cells with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP)-encoding vector (immunogenic) and the other half with a γ-globin-encoding vector (no predicted immunogenicity). After autologous transplantation of both transduced cell populations following myeloablative busulfan conditioning (5.5 mg/kg/day for 4 days), we observed immunological rejection of GFP-transduced cells up to 3 months post-transplant and stable engraftment of γ-globin-transduced cells in two animals, demonstrating that ablative busulfan conditioning is sufficient for engraftment of gene-modified cells producing non-immunogenic proteins but insufficient to permit engraftment of immunogenic proteins. We then added immunosuppression with abatacept and sirolimus to busulfan conditioning and observed engraftment of both GFP- and γ-globin-transduced cells in two animals, demonstrating that additional immunosuppression allows for engraftment of gene-modified cells expressing immunogenic proteins. In conclusion, myeloablative busulfan conditioning should permit engraftment of gene-modified cells producing non-immunogenic proteins, while additional immunosuppression is required to prevent immunological rejection of a neoantigen.

Keywords: busulfan conditioning, hematopoietic stem cells, gene therapy, immunological rejection

Myeloablative busulfan conditioning should permit engraftment of gene-modified cells producing non-immunogenic proteins, while additional immunosuppression (abatacept and sirolimus) is required to prevent immunological rejection of a neoantigen, evaluated by a rhesus hematopoietic stem cell gene-therapy model with lentiviral vectors encoding γ-globin (no predicted immunogenicity) or GFP (immunogenic).

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)-targeted gene therapy is curative for several immunodeficiencies1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and is under development for hemoglobin disorders, including sickle cell disease (SCD).6, 7 In current HSC gene-therapy strategies, a therapeutic gene is added to CD34+ cells by means of a lentiviral vector, and the transduced autologous cells are infused into the patient following conditioning. Conditioning can be considered to consist of two potentially independent goals: myelosuppression (myeloablation), or clearance of endogenous HSCs from marrow niches to allow for competitive engraftment of transplanted HSCs, and immunosuppression to prevent the immunologic rejection of transplanted HSCs.8 Total body irradiation (TBI)-based conditioning is traditionally used for allogeneic HSC transplantation, resulting in both myelosuppression and immunosuppression (as well as depletion of leukemia cells); however, it is toxic for multiple organs and increases mortality.8 In current gene-therapy trials, busulfan-based conditioning has been utilized due to its reduced toxicity compared to TBI and has yielded potent myelosuppression and HSC depletion. However, busulfan as a single agent has a minimal impact on immune-mediated rejection and is always combined with potent immunosuppressive therapies in allogeneic transplantation.9, 10 Therefore, we hypothesized that additional immunosuppression in combination with busulfan may be required for efficient engraftment of gene-modified cells that express a neoantigen.

To investigate this hypothesis, we used an HSC gene-therapy model in rhesus macaques that we had previously established.11, 12 In this non-human primate model, rhesus CD34+ cells were transduced with an enhanced EGFP (EGFP)-expressing lentiviral vector, and the transduced autologous cells were infused into the animal following ablative TBI conditioning (2 × 5 Gy), allowing for long-term engraftment of gene-modified cells.11, 12 Lower doses of TBI resulted in less efficient engraftment of gene-modified cells and more frequent immunological rejection of GFP protein, suggesting that additional myelosuppression and immunosuppression is required for engraftment of gene-modified cells.13, 14 TBI doses can be simply translated from a human to rhesus setting, while busulfan metabolism differs significantly between the two.15, 16 Therefore, in this study, we performed busulfan pharmacokinetics in rhesus macaques to optimize busulfan conditioning in a rhesus HSC gene-therapy model with lentiviral transduction.

Additional immunosuppression in combination with myeloablative conditioning is commonly used for allogeneic HSC transplantation. Calcineurin inhibitors including cyclosporine and tacrolimus are the most established drugs used to prevent graft rejection and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).8 Recently, several alternative immunosuppression medicines have been developed for allogeneic HSC transplantation. Abatacept is a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 immunoglobulin (CTLA4-Ig) that prevents T cell activation, while sirolimus is a mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor that inhibits lymphocyte proliferation.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 In this study, we investigated whether addition of abatacept and sirolimus to a myeloablative busulfan-conditioning regimen would permit efficient engraftment and prevent immunological rejection to transgenes in a rhesus HSC gene-therapy model.

Results

Engraftment of γ-Globin-Transduced Cells and Immunological Rejection of GFP-Transduced Cells in Rhesus Transplantation following Myeloablative Busulfan Conditioning

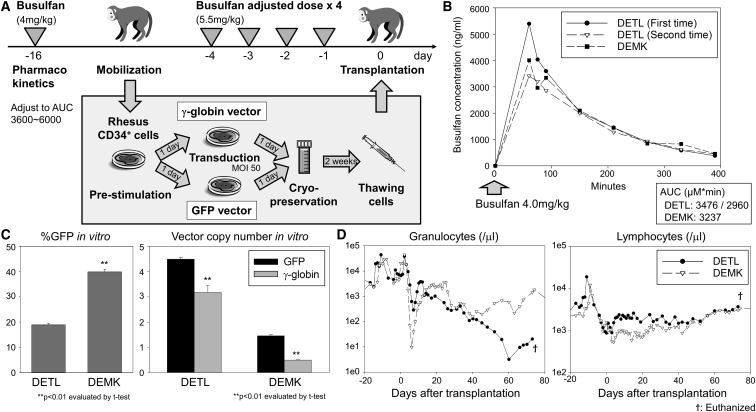

First, we performed busulfan pharmacokinetics in two animals (DETL and DEMK) to target an area under the curve (AUC) known to be myeloablative in human transplantation studies (Figure 1A). When 4 mg/kg busulfan was administered to animals with intravenous injection, busulfan AUCs (μM × min) were 2,936–3,237 in both animals (performed twice for DETL and one time for DEMK) (Figure 1B). Based on these AUC data, 5.5 mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days (days −4 to −1) was selected to adjust to an ablative AUC (3,600∼6,000), calculated by the assumption of linear pharmacokinetics, where AUC increases in direct proportion to dose.22 In two animals (DETL and DEMK), we transduced half of mobilized CD34+ cells with a GFP-encoding vector known to be immunogenic13, 14 and the other half with a human γ-globin-encoding vector without predicted immunogenicity, since globin genes have strong homology at DNA and protein levels between rhesus and human as well as within the β-globin series (β-, γ-, and ε-globins).23 In both animals, efficient transduction was observed in cultured CD34+ cells in vitro, as evaluated by GFP-positive percentages (%GFP) (19%–40%) and average vector copy numbers (VCNs) (1–4 for GFP and 1–3 for γ-globin) (Figure 1C). The transduced autologous cells were transplanted into animals following busulfan conditioning (Table 1). Busulfan conditioning resulted in strong suppression of granulocyte counts, hemoglobin concentration, and platelet counts, but only a mild reduction was observed in lymphocyte counts (Figure 1D; Figure S1A). Blood counts slowly recovered in DEMK, but despite the detection of short-term recovery (until 3 weeks post-transplant) in granulocytes in DETL, donor cells never adequately engrafted, and the animal (DETL) was euthanized on day 74 because sufficient blood counts could not be maintained with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) administration and blood transfusion.

Figure 1.

A Myeloablative Busulfan Conditioning for a Hematopoietic Stem Cell (HSC) Gene-Therapy Model with Lentiviral Transduction in Rhesus Macaques

(A) In two animals (DETL and DEMK), we transduced half of the mobilized CD34+ cells with a GFP-encoding lentiviral vector predicted to be immunogenic and the other half with a γ-globin-encoding lentiviral vector without predicted immunogenicity. The transduced cells were transplanted into autologous animals following an adjusted dose of busulfan conditioning (5.5 mg/kg/day × 4, days −4 to −1). (B) Busulfan pharmacokinetics was performed for DETL (twice) and DEMK (one time) with 4 mg/kg intravenous injection to target an ablative area under the curve (AUC). (C) We cultured small aliquots of rhesus CD34+ cells that were infused into the autologous animal and evaluated GFP-positive percentages (%GFP) in vitro in transduced CD34+ cells by flow cytometry and average vector copy numbers (VCNs) in vitro in GFP- or γ-globin-transduced CD34+ cells by qPCR. In vitro %GFP is more reliable to predict in vivo gene marking as compared to in vitro VCNs.32 (D) We analyzed granulocyte and lymphocyte counts before and after transplantation of transduced CD34+ cells. SEM is shown as error bars.

Table 1.

Variable Factors for Rhesus Transplantation

| Animal ID | Conditioning | Immunosuppression | Busulfan AUC (μM × min) | Infusion Cell Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DETL | busulfan (5.5 mg/kg × 4 days) | not applicable | 2,960–3,476a | 4.1e6/kg |

| DEMK | busulfan (5.5 mg/kg × 4 days) | not applicable | 3,237a | 2.5e6/kg |

| ZJ50 | busulfan (5.5 mg/kg × 4 days) | abatacept and sirolimus | 5,976 | 5.2e6/kg |

| ZJ32 | busulfan (5.5 mg/kg × 4 days) | abatacept and sirolimus | 5,956 | 4.2e6/kg |

| ZL42 | busulfan (5.5 mg/kg × 4 days) | abatacept (pre-transplant sirolimus) | 3,003 | 4.0e6/kg |

Following a test injection of 4 mg/kg busulfan.

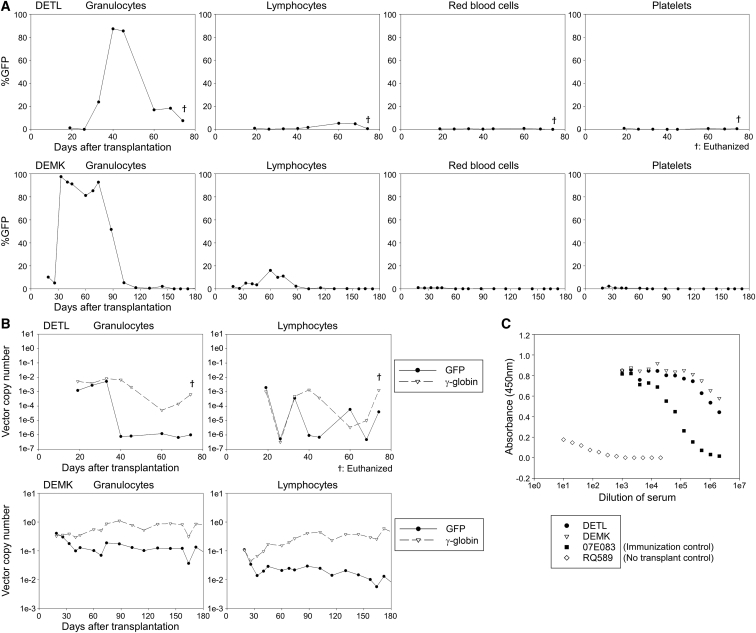

We observed high %GFP marking (∼90%) in granulocytes, but not in lymphocytes, red blood cells, and platelets, that persisted for only 1–2 months post-transplant in both animals, even though this level of GFP marking should have been impossible since only half of transplanted CD34+ cells were transduced with GFP vector (Figure 2A). After 3 months, GFP marking was no longer detectable by flow cytometry in any lineage in either animal. This pattern of “transient GFP positivity in almost all granulocytes” (probably resulting from phagocytosis of GFP protein), was previously observed in transplanted rhesus macaques experiencing immunological rejection to GFP following GFP transduction with low dose TBI conditioning.13 Fetal hemoglobin-producing red blood cells (F-cells) continued to be detected (∼6%) after 6–12 months in DEMK (Figure S2A). Overall, in vivo marking was much higher in DEMK than DETL, but in both animals, similar VCNs were observed for GFP and γ-globin initially. While γ-globin VCNs stabilized, GFP VCNs decreased to 100-fold lower levels by 2–3 months (Figure 2B). Anti-GFP antibodies were detected at 3 months in both animals (Figure 2C). These data demonstrate that ablative busulfan conditioning alone is sufficient for engraftment of γ-globin-transduced cells but insufficient to induce immunological tolerance to GFP. We hypothesize that the discrepancy between the very high GFP-positivity (>90%) and low VCNs (<0.01 in DETL and <0.2 in DEMK) in granulocytes occurred due to phagocytosis of GFP proteins by non-transduced granulocytes. While the mechanism responsible for the inadequate blood recovery in DETL has not been definitively determined, it is possible that the robust immune response directed at GFP may have had non-selective bystander effects that increased T cell activation against the graft, which may have negatively impacted engraftment of both transduced and non-transduced donor cells.

Figure 2.

Engraftment of γ-Globin-Transduced Cells and Immunological Rejection of GFP-Transduced Cells in Rhesus Transplantation following the Busulfan Conditioning

(A) We evaluated %GFP in peripheral blood cells after transplantation of transduced CD34+ cells in two animals (DETL and DEMK). (B) We evaluated VCNs for both GFP and γ-globin vectors in granulocytes and lymphocytes after transplantation. (C) We evaluated GFP antibody production in rhesus serum 3 months post-transplant, compared to an immunization control (07E083) and no transplantation control (RQ589). Serial dilutions of rhesus serum were added to GFP-coated plates, and GFP antibody signals were detected with a secondary antibody by an ELISA.

Engraftment of Both GFP- and γ-Globin-Transduced Cells following Busulfan Conditioning with Abatacept and Sirolimus Immunosuppression

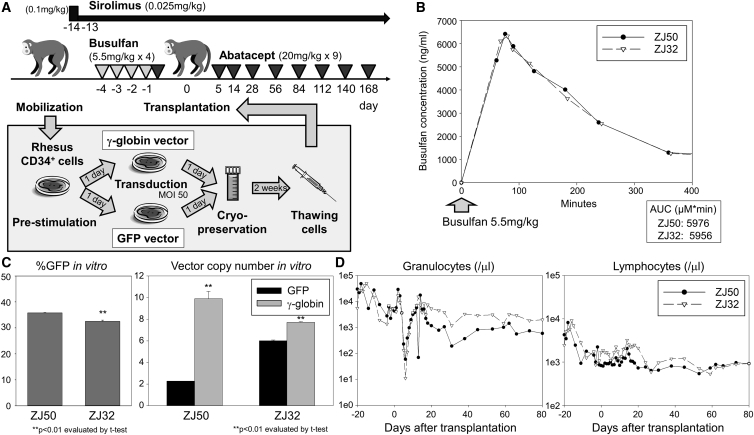

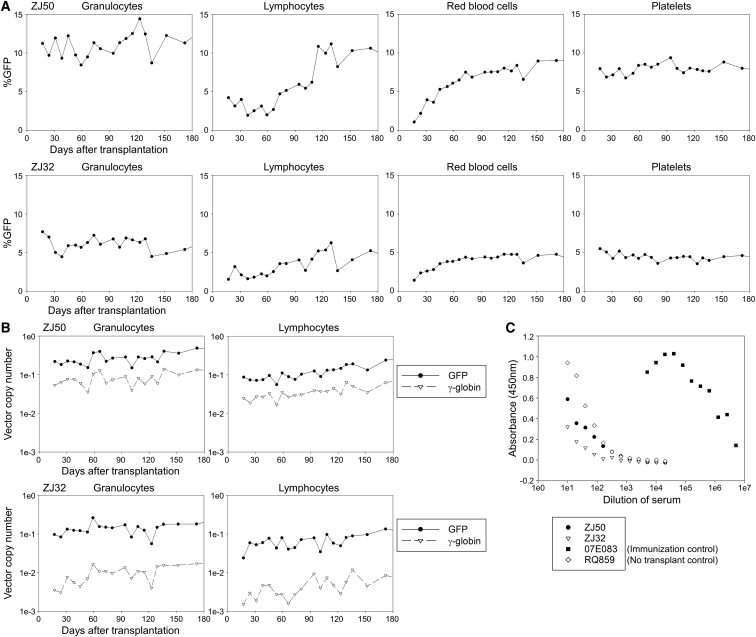

Next, we added immunosuppression with abatacept (20 mg/kg × 9, days −1, 5, 14, 28, 56, 84, 112, 130, and 168) and sirolimus (0.1 mg/kg, day −14; and 0.025 mg/kg, days −13 to 175) to the same busulfan-conditioning regimen (5.5 mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days, days −4 to −1) in two rhesus macaques (ZJ50 and ZJ32) (Figure 3A). In both animals, we confirmed ablative busulfan AUCs following the first cycle of 5.5 mg/kg busulfan injections (5,956–5,976) (Figure 3B) and therapeutic ranges of sirolimus concentration (10.3–14.3 ng/mL on day −3 and 13.0–15.2 ng/mL on day 52). We transduced rhesus CD34+ cells using the same culture and transduction conditions in all animals (GFP- and γ-globin vectors at MOI 50), and efficient transduction of CD34+ cells in vitro was achieved with both GFP- and γ-globin-vectors (VCNs 2–6 for GFP and 8–10 for γ-globin) (Figure 3C). The γ-globin VCNs were slightly higher in ZJ50 and ZJ32 but lower in DETL and DEMK, as compared to GFP VCNs (p < 0.01). After cell infusion (Table 1), severe suppression of granulocytes, hemoglobin concentration, and platelets, as well as mild suppression of lymphocytes, were observed in both animals, and robust recovery of blood counts occurred after transplantation (Figure 3D; Figures S1A and S1B). %GFP marking was stable and multi-lineage (3%–11%) (Figure 4A), and VCNs (0.07–0.27 for GFP and 0.004–0.08 for γ-globin) similarly remained stable in both animals for 6 months post-transplant (Figure 4B). F-cells were detected at 4%–6% levels out to 6 months (Figure S2B). No anti-GFP antibodies were detectable in either animal at 3 months (Figure 4C). These data demonstrate that the busulfan, abatacept, and sirolimus combination allows for engraftment of gene-modified cells, even those expressing highly immunogenic GFP protein.

Figure 3.

Addition of Abatacept and Sirolimus Immunosuppression to the Busulfan-Conditioning Regime in the Rhesus Gene-Therapy Model

(A) We added abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression to the busulfan-conditioning regime in two animals (ZJ50 and ZJ32). One-half of rhesus CD34+ cells were transduced with the GFP-encoding vector, and the other half were transduced with the γ-globin-encoding vector. (B) We evaluated busulfan AUCs after the first 5.5 mg/kg busulfan intravenous injection in the cycle. (C) We evaluated %GFP in vitro and VCNs in vitro in transduced CD34+ cells. (D) We evaluated granulocyte and lymphocyte counts in transplanted animals. SEM is shown as error bars.

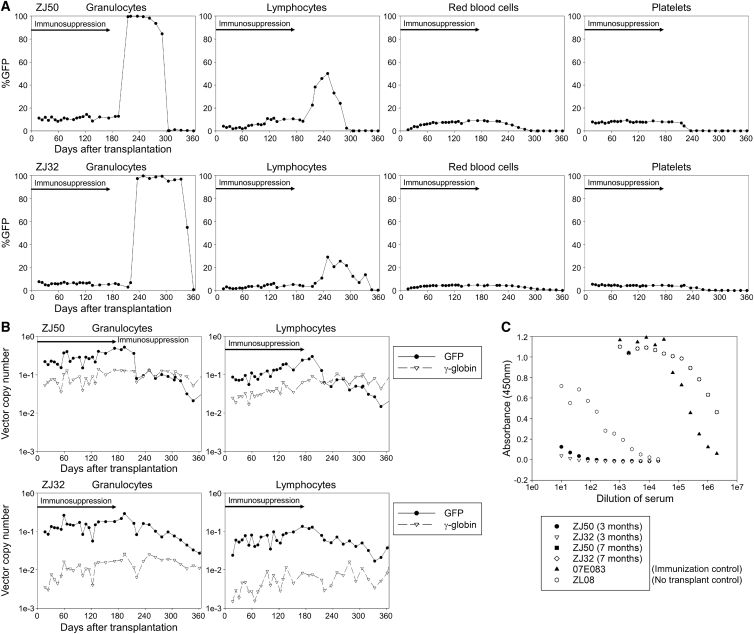

Figure 4.

Engraftment of Both GFP- and γ-Globin-Transduced Cells in Rhesus Transplantation with Busulfan, Abatacept, and Sirolimus Conditioning

(A) We evaluated %GFP in peripheral blood cells after transplantation in two animals (ZJ50 and ZJ32). (B) We evaluated VCNs for both GFP and γ-globin vectors in granulocytes and lymphocytes. (C) We evaluated GFP antibody production in rhesus serum 3 months after transplantation, compared to an immunization control (07E083) and no transplantation control (RQ589).

Immunological Response to GFP-Transduced Cells following Termination of Abatacept and Sirolimus Immunosuppression 6 Months Post-transplant

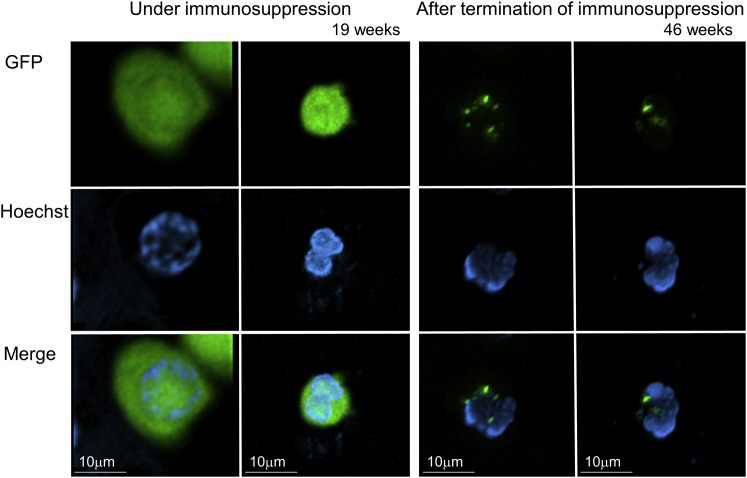

To investigate whether long-term immunosuppression is required for the engrafted animals following busulfan conditioning (ZJ50 and ZJ32) to maintain GFP marking, we terminated abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression 6 months post-transplant (day 176). Six to nine weeks after termination of immunosuppression, %GFP was transiently elevated to > 90% in granulocytes only (consistent with granulocytic phagocytosis of GFP proteins) and decreased to undetectable levels 10–12 months post-transplant (Figure 5A). When high percentages of GFP-positive cells (up to > 90%) were detected in granulocytes, low-intensity GFP expression was observed in flow cytometry (Figure S3). Using confocal microscopy, we observed several dense GFP signals in granulocytes (having segmented nucleus) 7 months post-transplant in ZJ32 (>90% of %GFP in granulocytes), which differs from the GFP localization pattern (diffuse GFP signals throughout the cytoplasm) in lentivirally transduced granulocytes with stable GFP marking 3 months post-transplant, suggesting that granulocytes phagocytized GFP protein (Figure 6). At 7 months post-transplant, GFP VCNs decreased to ∼10-fold lower amounts after termination of immunosuppression, while γ-globin VCNs remained stable (Figure 5B). F-cells remained detectable (2%–3%) for 1 year post-transplant (Figure S2B). Both animals tested positive for anti-GFP antibodies 7 months post-transplant, 2 months after immunosuppression was discontinued (Figure 5C). In mixed lymphocyte reaction for both animals 1.5 years post-transplant, higher levels of ex vivo lymphocyte proliferation (responder) were observed in the presence of irradiated GFP-positive autologous cells (stimulator) compared to non-transduced responder cells alone (p < 0.01 in ZJ50), while lymphocyte proliferation was not increased by GFP-positive stimulators in a tolerant control macaque with stable GFP marking (Figure S4). These data demonstrate that in the absence of abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression, rejection of GFP-expressing cells will occur. Longer dosing of these immunosuppressive drugs would be required to maintain engraftment after transplant.

Figure 5.

Immunological Response to GFP-Transduced Cells following Termination of Abatacept and Sirolimus Immunosuppression 6 Months Post-transplant

(A) We terminated abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression in the two engrafted animals (ZJ50 and ZJ32) 6 months post-transplant and evaluated %GFP in peripheral blood cells. (B) We evaluated VCNs for both GFP and γ-globin vectors in granulocytes and lymphocytes. (C) We evaluated GFP antibody production in rhesus serum 7 months post-transplantation (after termination of immunosuppression), compared to 3 months post-transplantation (under immunosuppression).

Figure 6.

Localization of GFP Proteins in Granulocytes for a Transplanted Rhesus Macaque Before and After Termination of Immunosuppression following Busulfan Conditioning

We evaluated GFP localization pattern in granulocytes for ZJ32 under immunosuppression (19 weeks post-transplant) with stable GFP marking (5%) as well as after termination of immunosuppression (46 weeks post-transplant) with GFP-positive in most granulocytes (96%), detected by Hoechst staining and confocal microscopy.

Discussion

We demonstrated efficient engraftment of gene-modified HSCs expressing both immunogenic and non-immunogenic transgenes in a rhesus gene-therapy model following a myeloablative busulfan-conditioning regimen combined with abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression (Figures 3 and 4). Busulfan conditioning alone allowed for engraftment of γ-globin-transduced cells (no predicted immunogenicity) but was insufficient to prevent immunological rejection of GFP-transduced cells (immunogenic) (Figures 1 and 2; Figure S4). Addition of abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression allowed for engraftment of both immunogenic GFP-transduced cells and non-immunogenic γ-globin-transduced cells (Figures 3 and 4). Termination of immunosuppression resulted in a rapid immune response to GFP, but not γ-globin (Figure 5), suggesting that immunosuppression should be maintained for longer than 6 months post-transplant to prevent immunological rejection to an immunogenic protein.

Busulfan metabolism is related to cytochrome P450 enzyme activities, while TBI effects are independent of metabolism.8, 24 Based on the busulfan pharmacokinetics in this rhesus study (Figure 1B), 5.5 mg/kg intravenous injection is optimal to target an ablative AUC (3,600–6,000). This is higher than the standard human dose (0.8 mg/kg intravenous injection and 1.0 mg/kg per oral administration), consistent with more rapid busulfan metabolism in rhesus macaques compared to humans.15, 16, 25 This adjustment of busulfan dosing is required to achieve myeloablation in rhesus transplantation and was well tolerated. Using this AUC-optimized dosing of busulfan, one animal who experienced rejection of transfused cells did not sufficiently recover peripheral blood cells after transplantation (Figure 1D; Figure S1A), suggesting that this dose of busulfan (5.5 mg/kg/day × 4 days) is myeloablative.

Myeloablation (opening HSC niches) is likely more important for efficient engraftment of gene-modified autologous cells in gene therapy than in the context of allogeneic HSC transplantation. We previously demonstrated that myeloablation allows for efficient engraftment of gene-modified autologous cells in a rhesus gene-therapy model with dose de-escalation of TBI conditioning.13, 14 In an allogeneic transplantation setting, donor lymphocytes can recognize recipient blood cells as non-self and remove recipient HCSs remaining in the patient’s bone marrow, enhancing donor chimerism. However, in gene therapy, autologous CD34+ HSCs are used for transduction, and the gene-modified blood lymphocytes derived from transduced HSCs should recognize recipient non-transduced HSCs as self, allowing them to remain in the bone marrow, where they compete with transduced HSCs. On the other hand, if gene-modified cells produce a neoantigen such as GFP, non-transduced lymphocytes may still recognize gene-modified blood cells as non-self and initiate anti-transgene adaptive immunity. Busulfan conditioning mainly leads to myelosuppression and HSC depletion with minimal impact on immune-mediated rejection,9 and in this rhesus study, ablative busulfan conditioning alone resulted in sustained engraftment of γ-globin-transduced cells (without predicted immunogenicity) but did not prevent immunological rejection to xenogeneic GFP (Figure 2). These data demonstrate that myeloablative busulfan conditioning allows for engraftment of gene-modified cells producing a non-immunogenic or less immunogenic protein such as γ-globin. Additional immunosuppression is required for engraftment of modified cells producing immunogenic protein such as GFP following busulfan conditioning.

Based on recent evidence for tolerance induction through costimulatory blockade, we explored abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression along with busulfan conditioning to allow for engraftment of GFP-transduced cells (Figure 3A). Abatacept is a CTLA4-Ig that prevents T cell co-stimulation, and it has been shown to improve engraftment and prevent GVHD in allogeneic HSC transplantation in human patients and rhesus macaques.19, 20, 21 Sirolimus is a mTOR inhibitor that prevents T cell proliferation in response to interleukin-2 and, when used in immunomodulating regimens in patients and rhesus macaques, has resulted in tolerance even after terminating drug administration.17, 18, 21 These immunosuppressive effects are possibly mediated by increasing Treg activity.26 In this study, we observed stable engraftment of gene-modified cells for both GFP and γ-globin in a rhesus gene-therapy model following myeloablative busulfan conditioning with additional abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression (Figure 4). These data demonstrate that additional immunosuppression in an ablative busulfan-conditioning regimen prevents immunological rejection of gene-modified cells producing an immunogenic protein such as GFP.

In the two animals with stable engraftment of gene-modified cells, termination of abatacept and sirolimus immunosuppression 6 months post-transplant was followed by immunological rejection of GFP around 2 months after termination of immunosuppression (Figures 5 and 6; Figure S4). The immunological reaction to GFP was confirmed by anti-GFP antibody production (Figure 5), positive mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) to GFP-positive autologous cells (Figure S4), dense GFP localization in granulocytes when > 90% of granulocytes were GFP positive (Figure 6), and reduction of GFP marking levels in vivo (Figure 5). The γ-globin-transduced cells remained stably engrafted after termination of immunosuppression. We previously demonstrated engraftment of GFP-transduced cells without immunological rejection in a rhesus gene-therapy model following myeloablative TBI conditioning without additional immunosuppression.11, 12 In a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donor transplantation with non-myeloablative conditioning, mixed chimerism remained stable after withdrawing immunosuppression, while graft cells were rejected after terminating immunosuppression in rhesus haploidentical transplantation with non-myeloablative conditioning.17, 18, 21 These data suggest that immunosuppression should be administered for longer than 6 months post-transplant in the busulfan-conditioning regimen and that immunoreaction to GFP might be precipitated by non-transduced lymphocytes remaining in transplanted animals, since these non-transduced lymphocytes recognize GFP-transduced cells as non-self. Furthermore, these data demonstrate that immunologic tolerance was not achieved, as rejection occurred upon removal of immunosuppression.

In another animal (ZL42), sirolimus immunosuppression was unintentionally administrated only from day −14 to day 0 in the rhesus gene-therapy model following busulfan conditioning with abatacept immunosuppression (Figures S1C and S5). Elevation of %GFP in granulocytes was slightly delayed under this partial immunosuppression; however, immunological rejection to GFP-positive cells occurred in ZL42 (Figures S2C and S6). These data suggest that the combination of long-term sirolimus and abatacept allows for prevention of in vivo immunological reaction to GFP in the busulfan-conditioning regimen.

These data are relevant to ongoing clinical trials involving gene transfer to patient HSCs, in which the amount of immunosuppression necessary to permit tolerance to a therapeutic protein product is not known. Though immunosuppression may not be necessary for genetic disorders resulting from a point mutation given the protein similarity, patients with null mutations that are not tolerant to the transgene encoded may indeed require not only myelosuppression, but also immunosuppression. In a SCD gene-therapy trial, patient CD34+ HSCs are transduced with a therapeutic βT87Q-globin-encoding lentiviral vector, and these transduced cells are transplanted following myeloablative busulfan conditioning without additional immunosuppression.7 βT87Q-globin is a variant of β-globin with one amino acid replacement (T87Q), and busulfan conditioning without additional immunosuppression allowed for engraftment of gene-modified cells expressing βT87Q-globin, suggesting that this variant is not immunogenic following ablative busulfan conditioning. Busulfan conditioning was also used for gene-therapy trials in immunodeficiencies.1, 2, 3 In this setting, gene-modified cells engrafted without additional immunosuppression in at least some of the patients despite patients receiving cells expressing a neoantigen. We previously demonstrated that busulfan conditioning without additional immunosuppression allows for engraftment of GFP-transduced human cells in immunodeficient mice.27 These data suggest that additional immunosuppression following busulfan conditioning is not required for engraftment of gene-modified cells in immunodeficient recipients, likely because the preexisting immunodeficiency is sufficient to prevent immunological rejection. In a successful gene-therapy trial for adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) patients who have normal immune systems and a defect in the ABCD1 gene, myeloablative conditioning with busulfan and additional immunosuppression with cyclophosphamide was used before transplantation of autologous CD34+ cells transduced with an ABCD1-encoding vector.28 As in this trial, when a therapeutic gene is added to patient CD34+ cells to produce a correct version of a defective protein and the recipient has a normal immune system, additional immunosuppression may be necessary to prevent immunological rejection of gene-modified cells.

In summary, myeloablative busulfan conditioning alone resulted in immunological rejection of HSCs transduced with GFP, while additional immunosuppression with abatacept and sirolimus allowed for engraftment of HSCs expressing either GFP or γ-globin and no immunoresponse to GFP while immunosuppression was being administered. Busulfan conditioning is more relevant than TBI for preclinical development using the macaque model. Busulfan conditioning alone may not allow for efficient engraftment of HSCs expressing a neoantigen—for instance, in patients that are protein null for the target gene prior to gene therapy—and additional immunosuppression with abatacept and sirolimus may be useful in these conditions.

Materials and Methods

Rhesus HSC-Targeted Gene-Therapy Model with Busulfan Conditioning

We developed a large animal model for HSC transplantation with lentiviral transduction in rhesus macaques following the guidelines set out by the Public Health Services Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under a protocol by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the NHLBI. We performed busulfan pharmacokinetics with 4mg/kg intravenous injection (Busulfex, PDL BioPharma, Redwood City, CA, USA) and adjusted to 5.5 mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days (days −4 to −1) to target an ablative AUC (3,600∼6,000), based on the assumption of linear pharmacokinetics, where AUC increases in direct proportion to dose. After G-CSF and plerixafor mobilization,29, 30 we transduced half of mobilized CD34+ cells with a GFP-encoding lentiviral vector and the other half with a γ-globin gene-encoding lentiviral vector without predicted immunogenicity.11, 12 The GFP cDNA was derived from a murine stem cell virus promoter, while the codon-optimized γ-globin cDNA was derived from an erythroid-specific β-globin promoter with enhancers (a locus control region and woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element), as previously described.31 Both GFP- and γ-globin vectors were prepared with chimeric gag/pol, rev/tat, vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein envelope and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) vector plasmids for efficient transduction in rhesus cells.11, 12 In two animals (DETL and DEMK), the transduced cells were transplanted into autologous animals following an adjusted dose of busulfan conditioning (5.5 mg/kg/day × 4, days −4 to −1). In two other animals (ZJ50 and ZJ32), we added immunosuppression with abatacept (20 mg/kg × 9, days −1, 5, 14, 28, 56, 84, 112, 130, and 168) (Orencia, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) and sirolimus (0.1 mg/kg, day −14 and 0.025 mg/kg, days −13 to 175) (therapeutic range 5–15 ng/mL) (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA) to the busulfan conditioning (5.5 mg/kg/day × 4, day −4 to −1). Small aliquots of infusion products (transduced rhesus CD34+ cells for transplantation) were cultured in vitro, and we evaluated %GFP in vitro in GFP-transduced CD34+ cells by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, Becton Dickinson, East Rutherford, NJ, USA) and VCNs in either GFP- or γ-globin-transduced CD34+ cells by qPCR (QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After transplantation, we analyzed complete blood counts to evaluate engraftment of transplanted rhesus CD34+ cells. Both %GFP and VCNs of GFP and γ-globin vectors were evaluated in peripheral blood cells.

Flow Cytometry

We evaluated %GFP in transplanted animals among granulocyte, lymphocyte, red blood cell, and platelet fractions identified by both forward scatter and side scatter using FACSCaliber (Becton Dickinson). The %fetal hemoglobin (γ-globin) containing red blood cells was detected by fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated fetal hemoglobin antibody (clone 2D12, Becton Dickinson) after permeabilization according to a company protocol.

qPCR

We evaluated VCNs in genomic DNA extracted from granulocytes and lymphocytes by the comparative methods (ΔΔCt methods) using the QuantStudio 6 flex real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The GFP vector (but not the γ-globin vector) was detected by self-inactivating long terminal repeat (SIN-LTR) probe and primers,32 and the γ-globin vector (but not the GFP vector) was detected by codon-optimized γ-globin probe and primers (GGopt forward primer, 5′-CAG CGG TTC TTC GAC AGC-3′; GGopt reverse primer, 5′-GGT CAG CAC CTT CTT GCC-3′; and GGopt probe, 5′-Cy5-GGC AAC CTG AGC AGC GCC AGC-3′). Both GFP and γ-globin signals (Ct values) were standardized by a control Ct value of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (TaqMan ribosomal RNA control reagents, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) to calculate GFP or γ-globin signal per cell (GFP-rRNA or γ-globin-rRNA ΔCt value). The GFP VCNs (ΔΔCt values for GFP VCNs) were calculated by a comparison to a control cell line including a single copy of GFP-encoding vector (a control GFP-rRNA ΔCt value for a known VCN = 1), and the γ-globin VCNs (ΔΔCt values for γ-globin VCNs) were calculated by a comparison to a control plasmid including both a single copy of GFP cDNA and a single copy of γ-globin cDNA (a control γ-globin-rRNA ΔCt value for a known VCN that is calculated by ΔΔCt values for GFP VCNs). In the transduced CD34+ cell analysis in vitro, in vivo gene marking levels (%GFP and VCNs) in rhesus granulocytes and lymphocytes can be predicted by in vitro %GFP, but in vitro VCNs are less reliable to predict in vivo gene marking due to contamination with vector plasmids.32

ELISA to Detect GFP Antibody Production

We evaluated GFP antibody production in rhesus serum 3 or 7 months post-transplant, compared to an immunization control (07E083) and no transplantation control (RQ589 or ZL08).13, 14 Serial dilutions of rhesus serum were added to GFP-coated plates, and GFP antibody signals were detected with anti-monkey immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody.

MLR to GFP-Positive Stimulator Cells

We evaluated ex vivo lymphocyte proliferation in response to GFP-positive autologous cells using MLR.13 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from transplanted animals (DEMK at 3.5 years post-transplant, ZJ50 at 1.5 years, and ZJ30 at 1.6 years). Rhesus PBMCs were stimulated on 12-well plates coated with CD3 antibody (clone FN-18, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and CD28 antibody (clone CD28.2; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) overnight and transduced with GFP-encoding vector at MOI 5. Following 25 Gy irradiation, 2e5 of GFP-transduced PBMCs (stimulator) were mixed 1:1 with 2e5 of autologous PBMCs (responder) in 96-well plates, which were stained with proliferation dye (CellTrace Far Red Cell Proliferation Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Two weeks later, proliferation percentages were evaluated by flow cytometry. PBMCs from a non-transplanted rhesus macaque were used as an allogeneic stimulator control, while monoculture of PBMCs without stimulators were used as a negative, no-proliferation control.

Confocal Microscopy

We evaluated localization of GFP protein in granulocytes from a transplanted macaque (ZJ32) using confocal microscopy. Rhesus granulocytes were isolated with mononuclear cell separation followed by red blood cell lysis from peripheral blood 19 weeks post-transplant (under immunosuppression with stable GFP marking) and 46 weeks post-transplant (after termination of immunosuppression with > 90% of GFP-positive granulocytes). Fresh granulocytes (unfixed) were stained by Hoechst 33342 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and GFP and Hoechst signals were detected by confocal microscopy using a Zeiss 780 LSM confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with a plan-apochromat 20× /0.8 objective lens. A 405-nm laser and an argon laser (488 nm) were used to excite Hoechst and GFP fluorescence, respectively. A series of images were taken throughout the depth of the cells, and images were deconvolved using Huygens Essential software 18.10.0p6 64b (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, the Netherlands) and reconstructed using Imaris software v 9.2.1 (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the JMP 11 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Two averages were evaluated by the Student’s t test. A p value of < 0.01 or < 0.05 was deemed significant. SEM was shown as error bars in all figures. All in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate.

Author Contributions

N.U. designed the research, performed experiments, analyzed results, made the figures, and wrote the paper; T.N. performed experiments; C.M.D. performed experiments and wrote the paper; J.G. performed experiments; M.Y. performed experiments; A.C.B. performed experiments; A.E.K. performed experiments; N.L. designed the research and performed experiments; M.M.H. designed the research; R.E.D. designed the research, C.E.D. designed the research, L.S.K. designed the research and performed experiments; J.F.T. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) at the NIH. We thank animal staffs and veterinarians at the NIH Animal Center for their support. We thank Thomas Hughes, PharmD, at the NIH Clinical Center for performing calculations to optimize busulfan injection dose. We thank Christian Combs, PhD, and Daniela Malide, MD, PhD, at the NHLBI Light Microscopy Core for helping with confocal microscopy.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.05.022.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Aiuti A., Cattaneo F., Galimberti S., Benninghoff U., Cassani B., Callegaro L., Scaramuzza S., Andolfi G., Mirolo M., Brigida I. Gene therapy for immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:447–458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiuti A., Slavin S., Aker M., Ficara F., Deola S., Mortellaro A., Morecki S., Andolfi G., Tabucchi A., Carlucci F. Correction of ADA-SCID by stem cell gene therapy combined with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Science. 2002;296:2410–2413. doi: 10.1126/science.1070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boztug K., Schmidt M., Schwarzer A., Banerjee P.P., Díez I.A., Dewey R.A., Böhm M., Nowrouzi A., Ball C.R., Glimm H. Stem-cell gene therapy for the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:1918–1927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavazzana-Calvo M., Hacein-Bey S., de Saint Basile G., Gross F., Yvon E., Nusbaum P., Selz F., Hue C., Certain S., Casanova J.L. Gene therapy of human severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)-X1 disease. Science. 2000;288:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5466.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hacein-Bey-Abina S., von Kalle C., Schmidt M., Le Deist F., Wulffraat N., McIntyre E., Radford I., Villeval J.L., Fraser C.C., Cavazzana-Calvo M., Fischer A. A serious adverse event after successful gene therapy for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:255–256. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200301163480314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavazzana-Calvo M., Payen E., Negre O., Wang G., Hehir K., Fusil F., Down J., Denaro M., Brady T., Westerman K. Transfusion independence and HMGA2 activation after gene therapy of human β-thalassaemia. Nature. 2010;467:318–322. doi: 10.1038/nature09328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ribeil J.A., Hacein-Bey-Abina S., Payen E., Magnani A., Semeraro M., Magrin E., Caccavelli L., Neven B., Bourget P., El Nemer W. Gene Therapy in a Patient with Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:848–855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Copelan E.A. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tutschka P.J., Santon G.W. Bone marrow transplantation in the busulfin-treated rat. III. Relationship between myelosuppression and immunosuppression for conditioning bone marrow recipients. Transplantation. 1977;24:52–62. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos G.W., Tutschka P.J., Brookmeyer R., Saral R., Beschorner W.E., Bias W.B., Braine H.G., Burns W.H., Elfenbein G.J., Kaizer H. Marrow transplantation for acute nonlymphocytic leukemia after treatment with busulfan and cyclophosphamide. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983;309:1347–1353. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198312013092202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchida N., Hargrove P.W., Lap C.J., Evans M.E., Phang O., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Nguyen A.-D., Hsieh M.M. High-efficiency transduction of rhesus hematopoietic repopulating cells by a modified HIV1-based lentiviral vector. Mol. Ther. 2012;20:1882–1892. doi: 10.1038/mt.2012.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchida N., Washington K.N., Hayakawa J., Hsieh M.M., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Donahue R.E., Tisdale J.F. Development of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-based lentiviral vector that allows efficient transduction of both human and rhesus blood cells. J. Virol. 2009;83:9854–9862. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00357-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uchida N., Weitzel R.P., Evans M.E., Green R., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Hsieh M.M., Donahue R.E., Tisdale J.F. Evaluation of engraftment and immunological tolerance after reduced intensity conditioning in a rhesus hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy model. Gene Ther. 2014;21:148–157. doi: 10.1038/gt.2013.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uchida N., Weitzel R.P., Shvygin A., Skala L.P., Raines L., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Donahue R.E., Tisdale J.F. Total body irradiation must be delivered at high dose for efficient engraftment and tolerance in a rhesus stem cell gene therapy model. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2016;3:16059. doi: 10.1038/mtm.2016.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang E.M., Hsieh M.M., Metzger M., Krouse A., Donahue R.E., Sadelain M., Tisdale J.F. Busulfan pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and low-dose conditioning for autologous transplantation of genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells in the rhesus macaque model. Exp. Hematol. 2006;34:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kahl C.A., Tarantal A.F., Lee C.I., Jimenez D.F., Choi C., Pepper K., Petersen D., Fletcher M.D., Leapley A.C., Fisher J. Effects of busulfan dose escalation on engraftment of infant rhesus monkey hematopoietic stem cells after gene marking by a lentiviral vector. Exp. Hematol. 2006;34:369–381. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh M.M., Fitzhugh C.D., Weitzel R.P., Link M.E., Coles W.A., Zhao X., Rodgers G.P., Powell J.D., Tisdale J.F. Nonmyeloablative HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe sickle cell phenotype. JAMA. 2014;312:48–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.7192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh M.M., Kang E.M., Fitzhugh C.D., Link M.B., Bolan C.D., Kurlander R., Childs R.W., Rodgers G.P., Powell J.D., Tisdale J.F. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:2309–2317. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaiswal S.R., Bhakuni P., Zaman S., Bansal S., Bharadwaj P., Bhargava S., Chakrabarti S. T cell costimulation blockade promotes transplantation tolerance in combination with sirolimus and post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for haploidentical transplantation in children with severe aplastic anemia. Transpl. Immunol. 2017;43-44:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koura D.T., Horan J.T., Langston A.A., Qayed M., Mehta A., Khoury H.J., Harvey R.D., Suessmuth Y., Couture C., Carr J. In vivo T cell costimulation blockade with abatacept for acute graft-versus-host disease prevention: a first-in-disease trial. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19:1638–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page A., Srinivasan S., Singh K., Russell M., Hamby K., Deane T., Sen S., Stempora L., Leopardi F., Price A.A. CD40 blockade combines with CTLA4Ig and sirolimus to produce mixed chimerism in an MHC-defined rhesus macaque transplant model. Am. J. Transplant. 2012;12:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zao J.H., Schechter T., Liu W.J., Gerges S., Gassas A., Egeler R.M., Grunebaum E., Dupuis L.L. Performance of Busulfan Dosing Guidelines for Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Conditioning. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardison R.C. Evolution of hemoglobin and its genes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a011627. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uppugunduri C.R., Rezgui M.A., Diaz P.H., Tyagi A.K., Rousseau J., Daali Y., Duval M., Bittencourt H., Krajinovic M., Ansari M. The association of cytochrome P450 genetic polymorphisms with sulfolane formation and the efficacy of a busulfan-based conditioning regimen in pediatric patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pharmacogenomics J. 2014;14:263–271. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2013.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radich J.P., Gooley T., Bensinger W., Chauncey T., Clift R., Flowers M., Martin P., Slattery J., Sultan D., Appelbaum F.R. HLA-matched related hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic-phase CML using a targeted busulfan and cyclophosphamide preparative regimen. Blood. 2003;102:31–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gliwiński M., Iwaszkiewicz-Grześ D., Trzonkowski P. Cell-Based Therapies with T Regulatory Cells. BioDrugs. 2017;31:335–347. doi: 10.1007/s40259-017-0228-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uchida N., Hsieh M.M., Hayakawa J., Madison C., Washington K.N., Tisdale J.F. Optimal conditions for lentiviral transduction of engrafting human CD34+ cells. Gene Ther. 2011;18:1078–1086. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eichler F., Duncan C., Musolino P.L., Orchard P.J., De Oliveira S., Thrasher A.J., Armant M., Dansereau C., Lund T.C., Miller W.P. Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Gene Therapy for Cerebral Adrenoleukodystrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1630–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donahue R.E., Kirby M.R., Metzger M.E., Agricola B.A., Sellers S.E., Cullis H.M. Peripheral blood CD34+ cells differ from bone marrow CD34+ cells in Thy-1 expression and cell cycle status in nonhuman primates mobilized or not mobilized with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and/or stem cell factor. Blood. 1996;87:1644–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida N., Bonifacino A., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Csako G., Lee-Stroka A., Fasano R.M., Leitman S.F., Mattapallil J.J., Hsieh M.M. Accelerated lymphocyte reconstitution and long-term recovery after transplantation of lentiviral-transduced rhesus CD34+ cells mobilized by G-CSF and plerixafor. Exp. Hematol. 2011;39:795–805. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchida N., Hsieh M.M., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Donahue R.E., Tisdale J.F. Development of a New Generation, Forward-Oriented Therapeutic Vector for Hemoglobin Disorders. Blood. 2016;128:1172. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12456-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchida N., Evans M.E., Hsieh M.M., Bonifacino A.C., Krouse A.E., Metzger M.E., Sellers S.E., Dunbar C.E., Donahue R.E., Tisdale J.F. Integration-specific In Vitro Evaluation of Lentivirally Transduced Rhesus CD34(+) Cells Correlates With In Vivo Vector Copy Number. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2013;2:e122. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.