Abstract

Ex vivo CD 34+ selection prior to allogeneic hematopoietic stem Cell transplantation (allo-HCT) reduces GVHD without increasing relapse, but usually requires myeloablative conditioning. We aimed to identify toxicity patterns in older patients & the association with overall survival (OS) & non-relapse mortality (NRM). We conducted a retrospective analysis of 200 pts who underwent CD34+ selection allo-HCT using the ClinicMACS® system between 2006-2012. All grade 3-5 toxicities by CTCAE v4.0 were collected. Eighty patients ≥ 60yrs with a median age of 64 (range 60-73) were compared to 120 pts <60yrs. Median follow-up in survivors was 48.2 months. OS and NRM were similar between ≥60 and <60, with a 1-yr OS 70% vs 78% (p=0.07) and 1-yr NRM, 23% vs 13% (p=0.38), respectively. In patients ≥60, the most common toxicities by day 100 were metabolic with a cumulative incidence of 88% (95% CI 78-93%), infectious 84% (73-90%), hematologic 80% (69-87%), oral/gastrointestinal (GI) 48% (36-58%), cardiovascular (CV) 35% (25-46%), & hepatic 25% (16-35%). Patients ≥60 had a higher risk of neurologic [HR 2.63 (1.45 to 4.78), p=0.001] and CV [HR 1.65 (1.04 to 2.63), p=0.03] toxicities, but lower risk of oral/GI [HR 0.58 (0.41 to 0.83), p=0.003] compared to <60. CV, hepatic, neurologic, pulmonary, & renal toxicities remained independent risk factors for the risk of death & NRM in separate multivariate models adjusting for age & HCT-CI. Overall, the toxicity of a more intense regimen is potentially balanced by the absence of toxicity related to methotrexate and calcineurin inhibitors in older patients. Prospective study of toxicities after allo-HCT in older patients is essential.

Introduction:

In the past decade, advances in therapy and supportive care have increased the number of older patients who are able to undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants (allo-HCT) with curative intent. Between 2007-2013, 22% of all allo-HCTs reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) were performed in patients over the age of 60, which was approximately double the number between 2000-20061. The majority of these patients have acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome and usually receive a reduced intensity conditioning (RIC) prior to transplant in order to mitigate the excess toxicities seen after fully ablative conditioning while maintaining a graft-versus-leukemia effect2. This approach has generally resulted in similar outcomes in older patients compared to younger patients, prompting the conclusion that age alone should not be a contraindication to transplant2–5.

The risk of non-relapse transplant related morbidity and mortality increases with the presence of more comorbidities pre-transplant and the development of acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allo-HCT6–8. T-cell depletion (TCD) through ex vivo CD 34+ selection of the graft prior to allo-HCT reduces GVHD without increasing relapse, but typically requires myeloablative conditioning (MAC)9–16. MAC remains important, as shown by the results of the Bone Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMT CTN) phase III 0901 trial, which found a statistically significant advantage in relapse-free survival in patients up to age 65 who received MAC compared to RIC17. Hence, the ability to mitigate toxicity without increasing the risk of relapse is vital to successful transplantation. This concept is being tested in younger patients in the on-going BMT CTN Protocol 1301 (), which is based on the benchmark analysis of novel GVHD prophylaxis approaches by the CIBMTR, and will compare ex-vivo CD34+ selection and the use of post-transplantation cyclophosphamide prospectively against the standard tacrolimus and methotrexate GVHD prophylaxis regimen18,19.

Systemic evaluation of toxicities after allo-HCT has been limited. Comprehensive collection of toxicities is particularly important in older patients in whom pre-existing comorbidities may increase the risk of adverse events after transplant. We therefore aimed to identify toxicity patterns in older patients and their association with overall survival (OS) and non-relapse mortality (NRM), and compare these with younger patients treated during the same time frame.

Methods:

Patients:

We retrospectively identified 200 sequential patients who underwent allo HCT for a hematologic malignancy with ex-vivo CD34+ selection using the CliniMACS® CD34 Reagent System (Miltenyi Biotech, Gladbach, Germany) at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) between 2006-2012. Patients were separated into two groups by age (18-59 or ≥ 60) for comparison. Data was gathered from the electronic medical record with a data-cutoff of December 31, 2015. Written informed consent for treatment was obtained from all patients and donors. Approval for this retrospective study was obtained from the MSKCC Institutional Review Board.

Conditioning Regimens/Graft Sources:

Patients were treated with one of three conditioning regimens per the discretion of the treating physician based on their age, comorbidity, disease type, and the trial options. Options included busulfan, melphalan, fludarabine; clofarabine, melphalan, thiotepa; total body irradiation (TBI), thiotepa, cyclophosphamide; or TBI, thiotepa, and fludarabine as previously described10,20,21. Briefly, the regimens were: (1) Busulfan 0.8mg/kg/dose every 6 hours x 10-12 doses (depending on disease), melphalan 70mg/m2/day for two days, and fludarabine 25mg/m2/day for five days. First dose busulfan pharmacokinetic monitoring was done to target an area-under-the-curve (AUC) range of 4100 – 5300 micromol*min/L. (2) Clofarabine 20mg/m2/day for five days, melphalan 70mg/m2/day for two days, and thiotepa 5mg/kg/day for 2 days. (3) Hyperfractionated TBI to 1375cGy administered in 125cGy fractions at 4-6 hour intervals three times per day, thiotepa 5mg/kg/day for 2 days, and cyclophosphamide 60mg/kg/day for two days. Fludarabine 25mg/m2/day for five days could be substituted for the cyclophosphamide. All patients received rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/day on days −3, −2. Patients who received a TBI-based preparative regimen received keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) 60 mcg/kg IV on days −13, −12, −11 and 0, +1, +2. All patients received peripheral blood grafts from either matched related or unrelated donors or mismatched related or unrelated donors.

Toxicities:

All ≥ grade 3 toxicities by CTCAE v4.0 were abstracted from start of conditioning to the date of relapse, progression (POD), or last follow-up by a member of the research team. Cross reviews of five patients for each abstractor were conducted to ensure consistency of collection with discrepancies settled by discussion with a 3rd investigator. Individual toxicities were organized into 91 toxicity categories and further into 17 organ-based groups (Supplement 1). Toxicities were also divided based on chronicity into 6 time periods: start of conditioning to day 100, day 101 to 6 months, 7-9 months, 10-12 months, 1-2 years, and beyond 2 years. One toxicity per organ based group per specified time period was used for statistical analyses. To avoid multiple counting, infectious toxicities were separated into febrile neutropenia without a source, febrile neutropenia with an identified source, neutropenic sepsis, non-neutropenic sepsis, and non-neutropenic bacteremia. Viral reactivations without organ disease were excluded and recurrence intervals for all infections were based on the CIBMTR classification22.

Outcomes:

Acute graft versus host disease (aGVHD) was captured from the institutional database after concensus grading at day 100 by the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry classification23. Late acute and chronic GVHD (cGVHD) were also captured and classified by the National Institutes of Health consensus criteria24. Non-relapse mortality (NRM), progression-free (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were calculated from start of conditioning.

Statistical Analysis:

Patients were grouped by disease into acute leukemia/MDS, multiple myeloma, or other. Cumulative incidences for each organ-based group were calculated and compared between the older and younger cohorts for toxicities occurring within the first 12 months, and separately for those occurring after 1 year using a 1-year landmark. Competing risks for this analysis included relapse, POD, second transplant, and death. Kaplan Meier survival curves were estimated for the older and younger cohort and in a second analysis evaluating survival based on the median number of toxicities by day 100. Univariate cause-specific Cox proportional hazard regression assessed the association with baseline covariates and the risk of toxicity development in the first year; this was assessed both in the subset over 60, and in the entire cohort to assess whether age > 60 was a risk factor for each toxicity. An additional analysis assessed age > 60 as a risk factor only among patients who received chemotherapy based conditioning without TBI.

Cox regression also assessed the univariate and multivariate associations for the endpoints of non-relapse mortality (NRM) and any-cause mortality in the patients over age 60. Toxicities were included as potential predictors in these models by treating each toxicity as a time-dependent covariate. Due to the number of events, separate models had to be built to evaluate the impact of each toxicity. Each multivariate model adjusted for age (by year over age 60) and HCT-CI, which were selected based on the number of events and the clinical importance of these two factors. Statistical analyses were conducted using R v3.3.2.

Results:

Characteristics:

Eighty patients aged 60 or older were compared to 120 patients <60 years (Table 1), with a median age in the older group of 64 (60-73) and in the younger group of 49 (19-59). The majority of patients in both groups had acute myeloid leukemia (AML), acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL), or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) (79 vs 66%). Multiple myeloma accounted for 11% of patients ≥ 60 and 18% of younger patients. Other diseases included chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=2 vs 0), chronic myelogenous leukemia (n=l vs 9), myeloproliferative disease (n=5 vs 4), non-hodgkin lymphoma (n= 0 vs 4), and familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (n= 0 vs 1). The median Hematopoietic Cell Transplant-Co-morbidity Index (HCT-CI) was 2 for both groups. Busulfan, fludarabine, and melphalan conditioning with rabbit ATG was used in 72% of patients. Only 2 older patients received TBI based conditioning compared to 45% in the younger group (p<0.001), and the majority of patients in both groups received grafts from matched related or unrelated donors. Median follow-up in survivors was 48.2 months.

Table 1:

Toxicity Sub-groups

| Characteristic | <60 yrs, n (%) | ≥60 yrs, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| N | 120 | 80 |

| Age, median (range) | 49 (19-59) | 64 (60-73) |

| Gender - Male | 59 (49) | 45 (56) |

| Disease | ||

| • AML/ALL/MDS | 80 (66) | 63 (79) |

| • Myeloma | 22 (18) | 9 (11) |

| • Other | 18 (15) | 8 (10) |

| HCT-CI | 2 (0–9) | 2 (0–10) |

| • 0 | 25 (21) | 17 (21) |

| • 1-2 | 43 (36) | 27 (34) |

| • ≥3 | 52 (43) | 36 (45) |

| Regimen with ATG | ||

| • Bu/Mel/Flu or Clo/Mel/Thio | 66 (55) | 78 (97) |

| • TBI/Thio/(Cy or Flu) | 54 (45) | 2 (3) |

| HLA | ||

| • MRD or MMRD | 47 (39) | 30 (38) |

| • MUD | 42 (35) | 36 (45) |

| • MMUD | 31 (26) | 14 (17) |

| Busulfan Change | ||

| • No Change | 30 (51) | 29 (40) |

| • Decrease | 7 (12) | 13 (18) |

| • Increase | 22 (37) | 30 (42) |

| CMV Positive Donor | 54 (45) | 43 (54) |

| CMV Positive Patient | 66 (55) | 46 (58) |

| Palifermin | 72 (60) | 24 (30) |

| ALC ≥ 0.05 | ||

| Ferritin | ||

| • <1000 | ||

| • 1000-2500 | ||

| • ≥ 2500 | ||

| Albumin ≥4 | ||

AML, acute myeloid leuekemia, ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; Bu, busulfan; Mel, melphalan; Flu, fludarabine; Clo, clofarabine; Thio, thiotepa; TBI, total-body irradiation; Cy, cyclophosphamide; HLA, human-leukocyte antigen; MRD, matched related donor; MMRD, mismatched-related donor; MURD, matched-unrelated donor; MMURD, mismatched unrelated donor; CMV, cytomegalovirus; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count.

Toxicities:

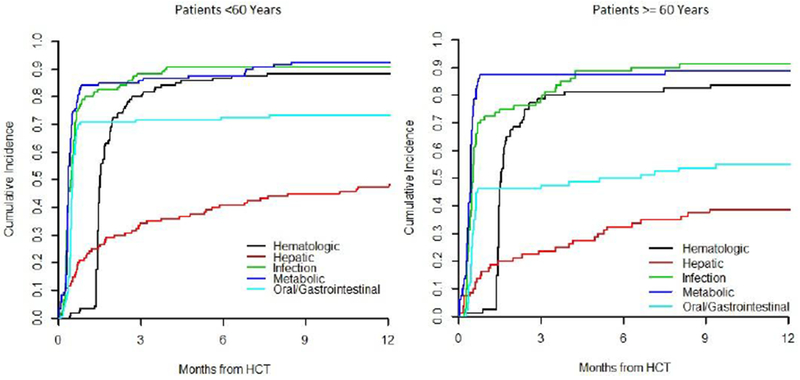

All patients had at least one ≥ grade 3 toxicity after transplant with the median number of toxicities at Day 100 equaling 6. Overall, the incidence of ≥ grade 3 toxicities was similar between the older and younger patients (Figure 1). In patients ≥60, the most common ≥ grade 3 toxicities by day 100 were metabolic with a cumulative incidence of 88% (95% CI 78-93%), infectious 84% (95% CI 73-90%), hematologic 80% (95% CI 69-87%), oral/gastrointestinal (GI) 48% (95% CI 36-58%), cardiovascular (CV) 35% (95% CI 25-46%), and hepatic 25% (95% CI 16-35%) (Supplement 2). By 1 year, 8/17 toxicity groups had a cumulative incidence over 20%: infectious 91% (95% CI 82-96%), metabolic 89% (95% CI 79-94%), hematologic 84% (95% CI 73-90%), GI 55% (95% CI 43-65%), CV 40% (95% CI 29-51%), hepatic 39% (95% CI 28-49%), neurologic 33% (95% CI 23-43%), and pulmonary 28% (95% CI 18-38%). Starting a 1-year post-transplant landmark, toxicities were less frequent by four years post-transplant with the most common late toxicities being infectious (cumulative incidence 34%, 95% CI 21-48%), hematologic (32%, 95% CI 19-45%), metabolic (26%, 95% CI 14-40%), hepatic (23%, 95% CI 12-36%), and CV (10%, 95% CI 4-21%).

Figure 1:

Cumulative Incidence

In the older patients, a total of 771 toxicities were identified by 1 year. Metabolic toxicities included electrolyte abnormalities (10% of total ≥ grade 3 toxicities in 1st year), hyperglycemia (6%), and anorexia (6%). Lung infections (3%), febrile neutropenia with a source (4%) and without a source (3%), and non-neutropenic bacteremias (3%) were the most common infectious complications. There was a low rate of ≥ grade 3 viral organ diseases by 1 year with 9 patients having organ disease from cytomegalovirus (CMV), 2 patients from adenovirus, and 2 patients from human herpes virus 6. Hematologic toxicities were primarily cytopenias after the first 30 days (15% of toxicities in the 1st year). GI side effects primarily included mucositis (4%) and diarrhea (2%). Atrial fibrillation (2%) and hypertension (1%) were the most common cardiovascular toxicities. Finally, the majority hepatic toxicities were abnormalities in liver function tests (LFTs, 5%).

After 1 year, the most common metabolic toxicities remained hyperglycemia (8% of the total 108 ≥ grade 3 toxicities after 1 year) and electrolyte abnormalities (7%). Late infectious toxicities were primarily lung infections (11%). Cytopenias accounted for 14% of the total toxicities identified after 1 year, while abnormalities in LFTs accounted for 10%. Finally, hypertension was the most common cardiac toxicity (4%).

When compared to patients younger than the age of 60, patients ≥60 had a higher risk of neurologic [HR 2.63 (1.45 to 4.78), p=0.001] and CV [HR 1.65 (1.04 to 2.63), p=0.03] toxicities, but lower risk of oral/GI side effects [HR 0.58 (0.41 to 0.83), p=0.003]. As older patients were less likely to received TBI, which may account for these differences, this analysis was repeated in the patients who received chemotherapy only conditioning in each group. Neurologic toxicities were the only toxicity at higher risk for older patients [HR 3.71 (1.61 to 8.56), p=0.002], while there was a lower risk of hepatic side effects [HR 0.6 (0.39 to 0.93), p=0.024].

Prognostic factors:

We then evaluated which pre-transplant factors were associated with the development of the most frequently identified toxicities in the first year for patients over 60. Factors tested by univariate analysis included age by year above 60, patient and donor gender, disease, relationship of donor, TBI based conditioning, palifermin use, adjustment of busulfan based on pharmacokinetics, cytomegalovirus (CMV) antibody positivity in the patient or donor, absolute lymphocyte count, ferritin, albumin, and HCT-CI. In the older patients, the risk of metabolic toxicity was increased if the donor was CMV seropositive [HR 1.9 (1.2-3.1), p=0.01], and decreased with albumin > 4 units/L [HR 0.6 (0.4-0.9), p=0.02] or the use of an unrelated donor [HR 0.5 (0.3-0.9), p=0.01]. Diagnosis of multiple myeloma (MM) was associated with increased hematologic toxicity [HR 3.04 (1.4-6.4), p<0.001] compared to AML, ALL, and MDS patients. The risk of oral/GI toxicity was increased with patient CMV seropositivity [HR 2 (1.1-3.9), p=0.03] and decreased in males [HR 0.5 (0.3-0.9), p=0.02]. Both ferritin >1000 ng/mL [HR 3.5 (1.5-7.9), p=0.002)] and patient CMV seropositivity [HR 2.8 (1.3-6.3), p=0.01] increased the risk of hepatic complications. No baseline characteristics were significantly associated with infectious or cardiovascular toxicities. Importantly, neither older age nor HCT-CI were associated with the development of particular toxicities.

Outcomes:

Acute GVHD rates were similar in both groups with grade 3-4 by day 100 seen in 7.5% in patients ≥60 and 2% in those <60. Late aGVHD was seen in 14% vs 20%, and moderate to severe cGVHD in 6% vs 2%.

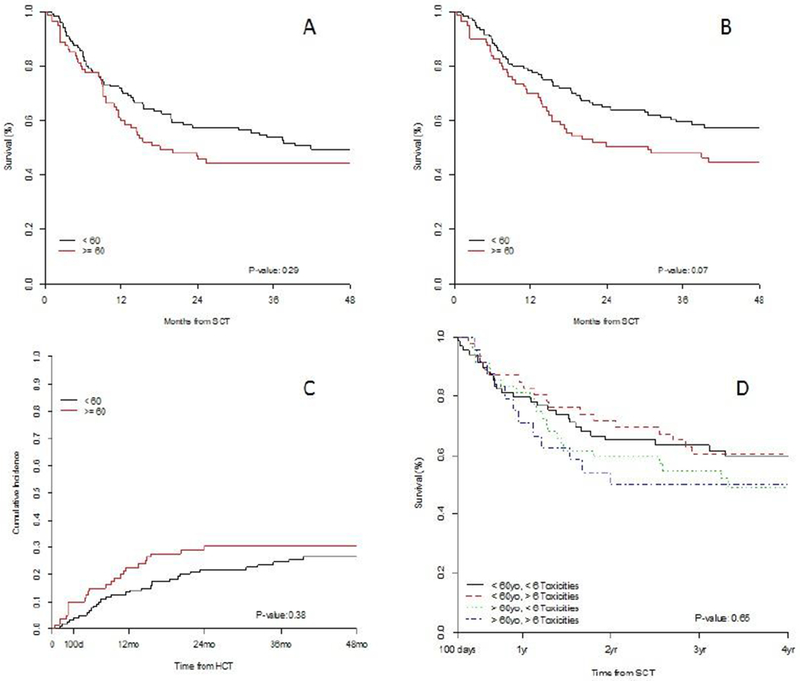

PFS was similar between the older and younger groups with 1-year PFS 60% (95% CI 50-72%) vs 71% (64-80%) and 3-year PFS 44% (35-57%) vs 54% (46-61%) respectively (logrank p=0.29; Figure 2A). OS was also not statistically different, with estimates at 1-yr of 70% (61-81%) vs 78% (71-86%) and at 3-years of 48% (38-60%) vs 60% (51-69%) , respectively(p=0.07, Figure 2B). One hundred day NRM was 10% (5-18%) vs 4% (2-9%); the one-year and 3-year estimates were also similar, 23% (14-32%) vs 13% (8-20%) and 30% (21-41%) vs 24% (17-33%), respectively. (p=0.38; Figure 2C).

Figure 2:

Survival Outcomes. A) PFS by age. B) OS by age. C) NRM by age. D) OS by age and number of toxicities by day 100.

To further evaluate the relationship between age, survival, and toxicity, we conducted a landmark analysis from day 100 with patients divided by age above and below 60 as well as above and below the median number of toxicities at day 100. In this analysis, OS was not significantly different in patients ≥60 with more than 6 toxicities by day 100 compared to pts with less than the median number of toxicities, and when compared to patients <60 years. Three-year OS was 55% (95% CI 42-71%) for patients over the age of 60 with <6 toxicities, 50% (36-75%) for over the age of 60 with ≥6 toxicities, 63% (48-77%) for <60 years and <6 toxicities, and 60% (53-76%) for <60 and ≥6 toxicities, (p=0.65, Figure 2D) .

In the older patients, univariate analysis of the baseline factors described above, as well as the 17 toxicity groups, was conducted to examine the relationships with NRM and OS (Table 2). NRM was increased with each year older than 60 (HR 1.2, p=0.004), the need to adjust busulfan dose lower (HR 3.1, p=0.03), patient CMV seropositivity (HR 2.7, p=0.04), and an HCT-CI ≥3 (HR 5.19, p=0.016). The diagnosis of MM compared to AML, ALL, and MDS was the only baseline characteristic associated with worse OS (HR 2.4, p=0.04). Neurologic (HR 8.49, p<0.001), renal (HR 7.7, p<0.001), CV (HR 5.14, p<0.001), pulmonary (HR 4.55, p<0.001), hepatic (HR 4.45, p<0.001), and skin toxicities (HR 3.2, p=0.02) increased the risk of NRM. Similarly, poorer OS was associated with renal (HR 4.77, p<0.001), endocrine (HR 3.7, p=0.03), neurologic (HR 3.44, p<0.001), pulmonary (HR 2.9, p=0.001), CV (HR 2.5, p=0.003), and hepatic (HR 1.92, p=0.04) toxicities (Appendix 1).

Table 2:

Univariate associations of baseline characteristics and toxicity with outcomes

| Risk of death | Risk of NRM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

| Age | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.2) | 0.077 | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.35) | 0.004 | |

| Male Sex | 1.35 (0.73 to 2.5) | 0.332 | 1.38 (0.6 to 3.16) | 0.445 | |

| Donor Male | 1.81 (0.84 to 3.92) | 0.13 | 1.17 (0.47 to 2.96) | 0.734 | |

| Disease Group | Acute Leukemia/MDS | (reference) | 0.039 | (reference) | 0.852 |

| Myeloma | 2.35 (1.07 to 5.15) | 1.28 (0.38 to 4.36) | |||

| Other | 0.42 (0.1 to 1.76) | 0.77 (0.18 to 3.3) | |||

| URD | 1.09 (0.59 to 2.03) | 0.783 | 1.03 (0.45 to 2.35) | 0.946 | |

| TBI | 2.8 (0.38 to 20.76) | 0.314 | 3.78 (0.5 to 28.49) | 0.196 | |

| Busulfan Change | No change | (reference) | 0.126 | (reference) | 0.029 |

| Decrease | 2.14 (0.92 to 4.95) | 3.13 (1.09 to 8.98) | |||

| Increase | 0.96 (0.46 to 1.99) | 0.8 (0.27 to 2.39) | |||

| CMV Pos Donor | 0.85 (0.47 to 1.54) | 0.585 | 1.65 (0.7 to 3.85) | 0.25 | |

| CMV Pos Patient | 1.38 (0.75 to 2.55) | 0.3 | 2.67 (1.06 to 6.73) | 0.037 | |

| Palifermin | 0.92 (0.47 to 1.79) | 0.797 | 1.44 (0.63 to 3.3) | 0.386 | |

| ALC | >=0.5 | 0.83 (0.3 to 2.32) | 0.72 | 2.01 (0.27 to 14.93) | 0.493 |

| Ferritin | <1000 | (reference) | 0.26 | (reference) | 0.71 |

| 1000-2500 | 1.82 (0.89 to 3.73) | 1.27 (0.47 to 3.43) | |||

| >2500 | 1.3 (0.48 to 3.5) | 1.59 (0.51 to 5.01) | |||

| Albumin | >=4 | 0.79 (0.43 to 1.45) | 0.448 | 0.6 (0.26 to 1.36) | 0.22 |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | 0.055 | (reference) | 0.016 |

| 1-2 | 1.52 (0.58 to 4) | 1.7 (0.33 to 8.76) | |||

| >=3 | 2.67 (1.09 to 6.54) | 5.19 (1.2 to 22.54) | |||

| Toxicity | Cardiovascular | 2.53 (1.38 to 4.62) | 0.003 | 5.14 (2.12 to 12.43) | <0.001 |

| Endocrine* | |||||

| Hematologic | 3.67 (1.14 to 11.86) | 0.03 | |||

| Hepatic | 1.92 (1.04 to 3.51) | 0.036 | 4.45 (1.93 to 10.3) | <0.001 | |

| Immune System* | |||||

| Infection | 1.3 (0.45 to 3.72) | 0.626 | 4.03 (0.53 to 30.5) | 0.177 | |

| Metabolic | 3.49 (0.84 to 14.46) | 0.084 | |||

| Musculoskeletal* | |||||

| Neurologic | 3.44 (1.87 to 6.31) | <0.001 | 8.49 (3.7 to 19.49) | <0.001 | |

| Ocular* | |||||

| Oral/Gastrointestinal | 1.1 (0.6 to 2) | 0.758 | 1.68 (0.73 to 3.84) | 0.22 | |

| Other | 2.29 (1.01 to 5.21) | 0.048 | 3.14 (1.15 to 8.58) | 0.025 | |

| Psychiatric* | |||||

| Pulmonary | 2.9 (1.56 to 5.39) | 0.001 | 4.55 (2.03 to 10.23) | <0.001 | |

| Renal and Urinary | 4.77 (2.37 to 9.59) | <0.001 | 7.67 (3.33 to 17.66) | <0.001 | |

| Reproductive System* | |||||

| Skin | 1.53 (0.6 to 3.9) | 0.373 | 3.2 (1.18 to 8.65) | 0.022 |

Could not be estimated based on the number who developed each toxicity.

A series of multivariate models assessed the association between the toxicities that were significant by univariate analysis and the risk of NRM or death in patients over 60 (Table 3). In each of the models for NRM, the toxicity remained independently significant (neurologic HR 8.43, p<0.001; renal HR 6.29, p<0.001; hepatic HR 5.13, p<0.001; pulmonary HR 4.04, p<0.001; and CV HR 3.99, p=0.005). In the models including cardiovascular, hepatic, neurologic, and renal toxicities, each year over the age of 60 also increased the risk of NRM. HCT-CI was not independently associated with an increased risk of NRM in any of the models. Similarly, the toxicities all remained predictive for OS (renal HR 4.19, p=0.001; neurologic HR 3.29, p<0.001; pulmonary HR 2.84, p=0.001; CV HR 2.16, p=0.017; and hepatic HR 2.1, p=0.019). Age by year over 60 was only independently associated in the models including neurologic and renal toxicities (HR 1.12 in each), and HCT-CI greater than 3 was significant only in the model including pulmonary toxicity (HR 2.52, p=0.049).

Table 3:

Multivariate analyses of age, HCT-CI, and toxicities that was significant based on a univariate analysis. Separate multivariate models were fit to each toxicity.

| Risk of Death HR (95% CI) | P-value | Risk of NRM HR (95% CI) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | 2.16 (1.15 to 4.08) | 0.017 | 3.99 (1.53 to 10.42) | 0.005 | |

| Age | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.17) | 0.236 | 1.15 (1.01 to 1.3) | 0.032 | |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | (reference) | ||

| 1-2 | 1.46 (0.56 to 3.86) | 0.441 | 1.47 (0.28 to 7.6) | 0.649 | |

| >=3 | 2 (0.8 to 5.02) | 0.139 | 2.77 (0.61 to 12.47) | 0.185 | |

| Hepatic | 2.1 (1.13 to 3.88) | 0.019 | 5.13 (2.15 to 12.24) | <0.001 | |

| Age | 1.1 (0.99 to 1.21) | 0.068 | 1.2 (1.06 to 1.36) | 0.003 | |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | 0.336 | (reference) | 0.521 |

| 1-2 | 1.61 (0.61 to 4.28) | 0.336 | 1.72 (0.33 to 8.95) | 0.521 | |

| >=3 | 2.35 (0.94 to 5.87) | 0.067 | 3.67 (0.82 to 16.54) | 0.09 | |

| Neurologic | 3.29 (1.73 to 6.25) | <0.001 | 8.43 (3.47 to 20.46) | <0.001 | |

| Age | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.23) | 0.023 | 1.24 (1.09 to 1.39) | 0.001 | |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | (reference) | ||

| 1-2 | 1.2 (0.44 to 3.23) | 0.722 | 0.81 (0.15 to 4.52) | 0.812 | |

| >=3 | 1.75 (0.69 to 4.45) | 0.237 | 2.02 (0.43 to 9.39) | 0.372 | |

| Pulmonary | 2.84 (1.49 to 5.4) | 0.001 | 4.04 (1.73 to 9.43) | 0.001 | |

| Age | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.15) | 0.345 | 1.12 (0.99 to 1.26) | 0.062 | |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | (reference) | ||

| 1-2 | 1.54 (0.58 to 4.07) | 0.387 | 1.51 (0.29 to 7.87) | 0.626 | |

| >=3 | 2.52 (1.01 to 6.32) | 0.049 | 3.92 (0.87 to 17.69) | 0.076 | |

| Renal | 4.19 (1.86 to 9.4) | 0.001 | 6.29 (2.37 to 16.7) | <0.001 | |

| Age | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.24) | 0.033 | 1.22 (1.08 to 1.39) | 0.002 | |

| HCT-CI | 0 | (reference) | (reference) | ||

| 1–2 | 1.4 (0.53 to 3.69) | 0.5 | 1.44 (0.28 to 7.47) | 0.665 | |

| >=3 | 1.59 (0.61 to 4.17) | 0.346 | 2.19 (0.46 to 10.36) | 0.324 |

HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index

Discussion:

We have conducted the most comprehensive assessment of toxicities of older patients after allo-HCT and found that the incidence and types of the most frequent toxicities are similar to younger patients. In addition, using the CD34+ selection platform, the OS and NRM are acceptable in patients above the age of 60.

Few studies have focused on the numbers or types of specific organ toxicities after allo-HCT. In the pediatric population, having 3 or more toxicities by day 30 conferred a high risk of treatment related mortality25. Similarly, we examined the impact of total toxicities on NRM and found that patients having above the median number of toxicities at day 100 also predicted for a higher risk of dying in both the older and younger adult patients. Maziarz et al then used a database of adult patients enrolled on six BMT CTN trials from 2003-2013 to study regimen related toxicity26. They included both autologous and allogeneic transplants and found that GI toxicities including diarrhea and mucositis were among the most common, but that pulmonary toxicities most frequently led to deaths. However, they found no correlation with low pre-HCT forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) or diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO). In our models, higher HCT-CI was associated with NRM by univariate analyses, but in the multivariate models with the toxicity categories, it was not independently predictive. For OS of the older patients, HCT-CI >3 was independently associated with survival only in the model including pulmonary toxicities. CMV seropositivity of the patient was associated with the development of several toxicities, and further investigation into the impact of this is warranted. We have previously shown that a high HCT-CI is associated with poorer outcomes in the CD34+ selected setting6. It is possible that we are not able to show this association in the older population due to the smaller sample size.

While for the majority of toxicities, the incidence was similar between the older and younger patients, there were a few important differences. First, neurologic toxicities were more common in older patients. This may be due to the interactions of medications used to control symptoms along with the increased likelihood of delirium among older patients admitted to hospitals27. GI and hepatic toxicities also appeared to be less frequent in patients ≥ 60, though the numbers are more equal when controlling for the use of TBI in the younger patients. Age does remain an important predictor of toxicity though. In our NRM models including cardiovascular, hepatic, neurologic, and renal toxicities and OS models for neurologic and renal toxicities, each year over age 60 did minimally, but significantly, increase the risk of these outcomes. Therefore, interventions to decrease these toxicities are crucial to expanding the benefits of allo-HCT to older patients.

Several recent papers have also evaluated the rates of GVHD and survival of older patients after allo-HCT. In a CIBMTR analysis including patients transplanted between 1995-2005 with AML in first remission and MDS, the 2-year OS for patients over 60 ranged from 34-55%2. NRM at 100 days was 10-19% and at 2 years was 32-39%. Grade ll-IV aGVHD by day 100 was seen in 33-35%. In a similar analysis evaluating patients over age 55 with B-cell ALL who underwent a RIC allo HCT between 2001-2012, Rosko et al reported a 3-year OS of 38% with 25% NRM and 47% relapse rates3. Grade II-IV aGVHD ranged from 27-42%. Similarly, the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplanation reported on allo-HCT for MDS patients over age 705. Three-year OS was 34%, with a relapse rate of 28%. One year NRM was 32% and day 100 grade II-IV aGVHD 27%. Finally, using the new composite end point of GVHD-free, relapse free survival (GRFS), the Cleveland Clinic reported a rate of 25% in patients over age 60 with AML, MDS, and CMML. In our analysis of patients over 60, we found a 3-year PFS of 44%, OS 48%, NRM 30%, and day 100 grade II-IV aGVHD rate of 12.5%. In this selected population who underwent TCD, we found improved outcomes compared to RIC.

Limitations of this study are primarily related to its retrospective nature. Inclusion of individual toxicities could only occur if there was appropriate documentation in the medical record. While it is likely that most severe toxicities are captured, multiple concurrent toxicities in prolonged complicated hospital stays may be over or underestimated when collected retrospectively28. As a quality control for our collection, we conducted cross reviews between abstractors and corrected discrepancies as they arose. In addition, we also incorporated all objective data such as laboratory values and culture results to confirm the inclusion of relevant toxicities. Furthermore, we created a classification scheme for cases in which multiple toxicities could be counted. We also acknowledge the sample size as a limitation, though this is the largest series of older patients treated with myeloablative conditioning and CD34 selection. Due to the small number of events of interest, the univariate and multivariate analyses are exploratory and should be prospectively confirmed.

In conclusion, patients over age 60 had an acceptable OS and NRM when compared to younger patients receiving a CD34 selected allograft, and the toxicity of a more intense regimen is potentially balanced by the absence of toxicity related to methotrexate and calcineurin inhibitors. While the median number of toxicities was similar between younger and older pts and to unmanipulated grafts based on reports of the BMT CTN, there was some difference in the type of toxicities by age. This first comprehensive toxicities assessment after CD34+ selected allo-HCT provides the basis for future studies, and prospective exploration of toxicities to further improve outcomes in this patient population is needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

OS and NRM were similar between patients ≥60 and <60 after CD34+ selected allo HCT.

Infectious, hematologic, and oral/gastrointestinal toxicities were common.

Most common toxicities were independent risk factors for death & NRM.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health award number P01 CA23766 and NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Additional support was provided by the Bergstein Family Foundation Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no other relevant conflicts of interests in relation to the work described.

References:

- 1.Pasquini M, Zhu X. Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2015. CIBMTR. http://www.cibmtr.org. Published 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McClune BL, Weisdorf DJ, Pedersen TL, et al. Effect of age on outcome of reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission or with myelodysplastic syndrome. JCO. 2010;28(11):1878–1887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosko A, Wang H-L, de Lima M, et al. Reduced Intensity Conditioned Allograft Yields Favorable Survival for Older Adults with B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. AJH. October 2016. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nazha A, Rybicki L, Abounader D, et al. GvHD-free, relapse-free survival after reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with myeloid malignancies. BMT. October 2016. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidenreich S, Ziagkos D, de Wreede LC, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome 70 years of age or older: A retrospective study of the MDS subcommittee of the Chronic Malignancies Working Party (CMWP) of the EBMT. BBMT. October 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barba P, Ratan R, Cho C, et al. Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index Predicts Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes Receiving CD34(+) Selected Grafts for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. BBMT. 2016;23(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorror ML, Logan BR, Zhu X, et al. Prospective Validation of the Predictive Power of the Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Comorbidity Index: A Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research Study. BBMT. 2015;21(8):1479–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorror ML, Martin PJ, Storb RF, et al. Pretransplant comorbidities predict severity of acute graft-versus-host disease and subsequent mortality. Blood. 2014;124(2):287–295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-550566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakubowski AA, Small TN, Young JW, et al. T cell depleted stem-cell transplantation for adults with hematologic malignancies: sustained engraftment of HLA-matched related donor grafts without the use of antithymocyte globulin. Blood. 2007;110(13):4552–4559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakubowski AA, Small TN, Kernan NA, et al. T cell-depleted unrelated donor stem cell transplantation provides favorable disease-free survival for adults with hematologic malignancies. BBMT. 2011;17(9):1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devine SM, Carter S, Soiffer RJ, et al. Low risk of chronic graft-versus-host disease and relapse associated with T cell-depleted peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia in first remission: results of the blood and marrow transplant clinical trials network prot. BBMT. 2011;17(9):1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasquini MC, Devine S, Mendizabal A, et al. Comparative outcomes of donor graft CD34+ selection and immune suppressive therapy as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis for patients with acute myeloid leukemia in complete remission undergoing HLA-matched sibling allogeneic hematopoietic cell transpl. JCO. 2012;30(26):3194–3201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayraktar UD, de Lima M, Saliba RM, et al. Ex vivo T cell-depleted versus unmodified allografts in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission. BBMT. 2013;19(6):898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldberg JD, Linker A, Kuk D, et al. T cell-depleted stem cell transplantation for adults with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: long-term survival for patients in first complete remission with a decreased risk of graft-versus-host disease. BBMT. 2013;19(2):208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobbs GS, Hamdi A, Hilden PD, et al. Comparison of outcomes at two institutions of patients with ALL receiving ex vivo T-cell-depleted or unmodified allografts. BMT. 2015;50(4):493–498. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamari R, Chung SS, Papadopoulos EB, et al. CD34-Selected Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants Conditioned with Myeloablative Regimens and Antithymocyte Globulin for Advanced Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Limited Graft-versus-Host Disease without Increased Relapse. BBMT. 2015;21(12):2106–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Logan B, et al. Results of a Phase III Randomized, Multi-Center Study of Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation after High Versus Reduced Intensity Conditioning in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome (MDS) or Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML): Blood and Marrow Transplant Cli. In: Blood. Vol 126 ; 2015:LBA–8. http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/126/23/LBA-8?sso-checked=true. Accessed November 14, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alousi AM, Bolaños-Meade J, Lee SJ. Graft-versus-host disease: state of the science. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(1 Suppl):S102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCurdy SR, Kasamon YL, Kanakry CG, et al. Comparable composite endpoints after HLA-matched and HLA-haploidentical transplantation with posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Haematologica. October 2016. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.144139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papadopoulos EB, Carabasi MH, Castro-Malaspina H, et al. T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation as postremission therapy for acute myelogenous leukemia: freedom from relapse in the absence of graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1998;91(3):1083–1090. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9446672. Accessed December 21, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro-Malaspina H, Jabubowski AA, Papadopoulos EB, et al. Transplantation in remission improves the disease-free survival of patients with advanced myelodysplastic syndromes treated with myeloablative T cell-depleted stem cell transplants from HLA-identical siblings. BBMT. 2008;14(4):458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomblyn M CIBMTR Infection Data CIBMTR Infection Data and the New Infection and the New Infection Inserts Inserts. https://www.cibmtr.org/Meetings/Materials/CRPDMC/Documents/2007/february/TomblynM_Infection.pdf Published 2007. Accessed November 14, 2016.

- 23.Rowlings PA, Przepiorka D, Klein JP, et al. IBMTR Severity Index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease: retrospective comparison with Glucksberg grade. BJH. 1997;97(4):855–864. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9217189. Accessed November 14, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filipovich AAH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. BBMT. 2005;ll(12):945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Mulla N, Kahn JM, Jin Z, et al. Survival Impact of Early Post-Transplant Toxicities in Pediatric and Adolescent Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Malignant and Nonmalignant Diseases: Recognizing Risks and Optimizing Outcomes. BBMT. 2016;22(8): 1525–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maziarz RT, Lazarus HM, Riches ML, Mudrick C, Mendizabal A. BMT CTN trials: A rich source for regimen related toxicity assessments in the modern era. BBMT. 2016;22(3 SUPPL. 1):S291–S292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.11.746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han JH, Wilber ST. Altered Mental Status in Older Patients in the Emergency Department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29(1):101–136. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rafter N, Hickey A, Conroy RMRM, et al. The Irish National Adverse Events Study (INAES): the frequency and nature of adverse events in Irish hospitals—a retrospective record review study. BMJ Qual Saf. February 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.