Abstract

Rationale and objectives:

Magnetic resonance elastography has proven to be a valuable tool in the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, breast and cervical cancer, but its application in uterine fibroids requires further characterization. The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between uterine fibroid stiffness by MRE and MR imaging characteristics.

Materials and methods:

An IRB-approved, HIPAA compliant review was performed of prospectively collected pelvic MRI and 2D-MRE data in patients with symptomatic uterine fibroids (N = 102). T1 and T2 weighted pelvic MRI with gadolinium enhancement were performed. In a small patient subset, fibroid stiffness was assessed by both 2D and 3D MRE. Fibroid stiffness by modality or imaging characteristics was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Student t test.

Results:

Four fibroid groups were identified based on T2 appearance: Isointense (N = 7), bright (N = 6), dark with minimal heterogeneity (N = 69), and dark with substantial heterogeneity (N = 20). Mean fibroid stiffness was 4.81 ± 2.12 kPa. Comparison of fibroid stiffness by T2 signal intensity showed that T2 bright fibroids were significantly less stiff than fibroids appearing T2 dark with minimal heterogeneity (mean stiffness difference = 2.38 kPa; p < 0.05) and T2 dark fibroids with substantial heterogeneity were significantly less stiff than T2 dark fibroids with minimal heterogeneity (mean difference = 1.25 kPa; p < 0.05). There was no significant association between fibroid stiffness and T1 signal characteristics or gadolinium enhancement. There was no significant difference in stiffness values obtained by either 2D vs. 3D MRE.

Conclusions:

These data suggest differences in fibroid stiffness are associated with different T2 imaging characteristics with less stiff fibroids being T2 bright and more stiff fibroids being T2 dark. Further studies are needed to determine if fibroid stiffness by MRE may serve as an imaging biomarker to help predict MR-guided treatment response.

Keywords: Fibroid, Leiomyoma, Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Leiomyomas, or fibroids, are benign, monoclonal tumors of the myometrium that are prevalent in approximately 70% of Caucasian women and symptomatic in one of four with an even higher burden among women of African-American descent with an estimated prevalence of 80% or higher [1, 2], Although benign, these neoplasms can cause serious symptoms such as prolonged or heavy menses, dysmenorrhea, increased urinary frequency, dyspareunia, infertility, and remain the leading reason women undergo hysterectomy [3–5], While hysterectomy remains the most definitive treatment for symptomatic leiomyomas, it is also the most invasive, leading many to consider alternative methods. Other treatment options for uterine leiomyoma include hormonal or pharmacologic therapies, myomectomy, uterine artery embolization (UAE), or magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound ablation (MRgFUS, FUS) [6], There has been growing interest in MRgFUS as a non-invasive thermo-ablative technique for the treatment of uterine fibroids. MRgFUS uses high-intensity focused ultrasound waves to generate heat and destroy tissue in a region of interest using MR guidance for anatomic specification, beam direction, and thermal monitoring[7], While FUS has proven to be successful in the treatment of common uterine leiomyoma, those of high signal intensity in T2 weighted MRI have proven to be less amenable to FUS ablation as measured by the need for additional treatment [8, 9], This raises questions about how the fibroid mechanical properties can differentially affect treatment responsiveness and whether a better means of fibroid characterization would serve to better predict treatment response.

Leiomyomas are characterized by an altered state of mechanical homeostasis, such that they are significantly stiffer upon palpation than adjacent matched myometrium, and for this reason are commonly referred to as fibroids [10], The increased firmness compared to the myometrium results from an excess of extracellular matrix in addition to irregular collagen structure and organization [11, 12], Palpation can assess the mechanical properties of soft tissue by its elasticity, which is the ratio of given stress to the resulting strain. Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is a non-invasive technique that measures the elastic properties of a tissue by inducing harmonic vibrations of acoustic-range frequencies in the tissue of interest, imaging the propagation of those vibrations within the tissue and using that data to generate a stiffness map, elastogram, and quantitative values for the tissue’s mechanical properties [13–15].

MRE as well as other forms of elastographic data have proven to be a valuable tool in the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, breast and cervical cancer, but its application in uterine fibroids remains relatively new [16–21], Previous studies have shown MRE to be a feasible mechanism for the characterization of uterine fibroids in a small sample group of women with planned excisional surgery for uterine leiomyomas [22], However, there have been no further studies on MRE characterization of uterine fibroids, and therefore we sought to expand on the feasibility study to better characterize the elastic properties of uterine fibroids as well as the potential role MRE may play in their diagnosis and clinical care. The principal aim of this study was to acquire 2D-MRE gradient-echo-based sequence acquisition data from clinically indicated pelvic MRIs on women with uterine fibroids, and to examine the correlation between MRE-derived stiffness values and MRI signal characteristics of the fibroid. Additionally, we sought to assess the feasibility of 3DMRE multi-slice spin-echo-based echo planner imaging sequence in uterine fibroids in a much smaller second patient subset. The reason for the second subset 3D MRE acquisition is that this has the potential to give a much better volumetric analysis of the fibroids than selected 2D slice acquisitions.

Materials and methods

Patient population and data collection

This was a single-arm prospective pilot study to determine whether MR Elastography can be optimized for clinical use as part of the patient’s routine clinical imagining. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (#10-002112), and determined to be a non-significant risk procedure. Women between 18 and 89 years of age scheduled for a clinically indicated pelvic MRI for uterine fibroids or other uterine problems were considered for this study. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study. Patients’ clinical data were acquired via retrospective review of their clinical charts. Study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the revised Declaration of Helsinki.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI scans were performed with a 1.5-T system (Signa, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a phased-array pelvic coil. The standard uterine fibroid imaging protocol includes the following sequences: axial, sagittal, and coronal fast spin-echo T2 weighted sequence, axial dynamic 3D fat-saturated spoiled gradient-echo sequence (pelvic acquisition with volume acceleration) before and after administration of a contrast agent, and delayed 2D axial, sagittal, and coronal fast spoiled gradient-echo sequence. Gadodiamide (Omniscan, GE Healthcare) 0.1 mmol/kg or Gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance, Bracco) 0.05 mmol/kg was injected IV at a rate of 2–3 mL/s with an automated injector and was followed by a 30 mL saline flush. A 2 mL bolus was administered to determine scan delay after contrast injection to optimize the arterial phase acquisition. All sequences were performed with a breath-hold at end-respiration.

All images were reviewed by an experienced radiologist and fibroid appearance was classified by signal intensity into one of four groups in T1 and T2 weighted MRI series. Fibroids in T1 weighted images were identified as isointense, hypointense, hyperintense, or heterogeneous compared to myometrium. Fibroids were classified as heterogeneous if they appeared as both hypo- and hyperintense compared to myometrium. In T2 weighted images fibroids were again classified into four groups by their signal intensity compared to myometrium; fibroids appeared isointense, bright or dark. T2 dark fibroids were then further classified as having minimal heterogeneity or substantial heterogeneity if the fibroid had regions of high and low signal intensity. Gadolinium contrast enhancement was assessed by fibroid signal intensity compared to the myometrium. Many women presented with multiple fibroids, and therefore the largest fibroid was selected for volumetric and imaging characteristic analysis. Fibroids less than one centimeter are difficult to evaluate due to the resolution of the MRE in part because of the wave length chosen for excitation (60 Hz). Therefore in this study, the comparisons were made in the largest fibroid contained within the uterus due to the likelihood that this fibroid was contributing the most to the patient symptomology.

Magnetic resonance elastography

Following MRI protocol, participants were imaged in the supine position while a 19-cm-diameter passive driver was placed on their abdomen above the uterus. In women with multiple fibroids, the largest fibroid was targeted for MRE data acquisition. An active driver in the equipment room transmitted continuous acoustic vibrations through a flexible vinyl tube to the passive driver which transmitted shear waves into the uterus. Wave images were collected using a modified two-dimensional (2D) gradient-recalled echo-based elastography pulse sequence with the following parameters: imaging plane = axial; field of view (FOV) = 24–42 cm; matrix = 256 × 64; fractional-phase FOV = 0.75–1; flip angle = 30°; number of excitations (NEX) = 1; bandwidth = 31.25 kHz; TR = 50 ms; TE = 18.4 ms; slice thickness 10 mm; slice position through the uterine fibroid; slice number = 4; phase offsets = 4; motion encoding sensitivity (MENC) = 22 μm/π-radian; MRE driver frequency = 60 Hz (chosen for improved penetration within the pelvis); and MSG direction = through plane; scan time = 59 s (4 breath-holds).

2D-MRE wave images were processed with a MRE 2D inversion algorithm yielding 4 slices of fibroid elastograms. Region(s) of interest (ROI) were drawn on the fibroid, avoiding non-fibroid or necrotic tissue if present, using corresponding T2 images as a guide. From the ROI, mean stiffness (kPa) and standard deviation were reported.

In a subset of patients, additional 3D MRE was acquired using a MRE multi-slice spin-echo-based echo planner imaging sequence. The selection criteria for patients with 3D MRE were the same criteria as 2D MRE. The 3D MRE was only implemented on a limited number of scanners necessitating specialized scheduling to a particular scanner so due to these technical aspects only a limited number were performed for a small comparison subset. The 3D MRE was acquired with the following parameters: imaging plane = axial; field of view (FOV) = 44.8 cm; matrix = 96 × 96; fractional-phase FOV = 1; number of excitations (NEX) = 1; bandwidth = 125 kHz; TR = 1333.8 ms; TE = 44.0 ms; slice thickness = 3.5 mm; slice position through the uterine fibroid; slice number = 32; phase offsets = 3; motion encoding sensitivity (MENC) = 31.4 μm/π-radian; MRE driver frequency = 60 Hz; motion encoding direction = three orthogonal directions; and scan time = 1 min 04 s (4 breath-holds). 3D-MRE wave images were processed using a MRE 3D inversion algorithm, resulting in 32 slices of fibroid elastograms. The first and last 4 slices within the MRE imaging dataset were discarded to avoid aliasing artifact. ROIs were drawn on the fibroid elastograms, and non-fibroid tissue and necrosis were avoided if present; mean stiffness and standard deviation were reported.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 10.0.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Mean fibroid stiffness values and MRI signal characteristics were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance followed by pairwise comparison using both the Student t test and Tukey–Kramer test. The level for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

102 patients comprise the study population, where mean participant age was 44 ± 8.8 years, and 95% were either pre- or perimenopausal. The majority of participants (87%) reported heavy menstrual bleeding, often accompanied by other symptoms such as painful periods, increased urinary frequency, pain/pressure in the abdomen/back. Mean fibroid volume and stiffness were 283.0 ± 398.0 cm3 and 4.81 ± 2.12 kPa, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient population clinical characteristics

| Subject characteristics | Mean ± SD or % sample population |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.4 ± 8.8 |

| Reproductive status | |

| Premenopausal | 67% |

| Perimenopausal | 28% |

| Menopausal | 5% |

| Symptoms | |

| Menorrhagia | 87% |

| Dysmenorrhea | 36% |

| Urinary frequency | 50% |

| Pain or pressure | 63.7% |

| Planned procedure | |

| None | 38.2% |

| FUS | 12.8% |

| UAE | 14.7% |

| Surgery | 34.3% |

| Fibroid characteristics | |

| Single fibroid | 21% |

| Multiple fibroids | 79% |

| Volume (cm3) | 283.0 ± 398.0 |

| Range of volume (cm3) | 3082.0 |

| Stiffness (kPa) | 4.81 ± 2.12 |

| Range of stiffness (kPa) | 10.4 |

| Type (location) | |

| Submucosal | 16.7% |

| Intramural | 73.5% |

| Subserosal | 5.9% |

| Pedunculated | 3.9% |

| T1 appearance | |

| Isointense | 84% |

| Hypointense | 4% |

| Hyperintense | 4% |

| Heterogeneous | 4% |

| No T1 Images | 4% |

| T2 appearance | |

| Dark/minimal heterogeneity | 67.6% |

| Dark/substantial heterogeneity | 19.6% |

| Isointense | 6.9% |

| Bright | 5.9% |

| Contrast enhancement | |

| Greater/equal | 57.9% |

| Less | 30.4% |

| None | 6.9% |

| No Gd administered | 4.9% |

Clinical characteristics of 102 patients with successfully obtained 2D MRE. Fibroid characteristics, volume, stiffness, type (location), and MRI appearance, are also shown. Mean ± SD or percent of sample population is used to represent each characteristic unless otherwise indicated

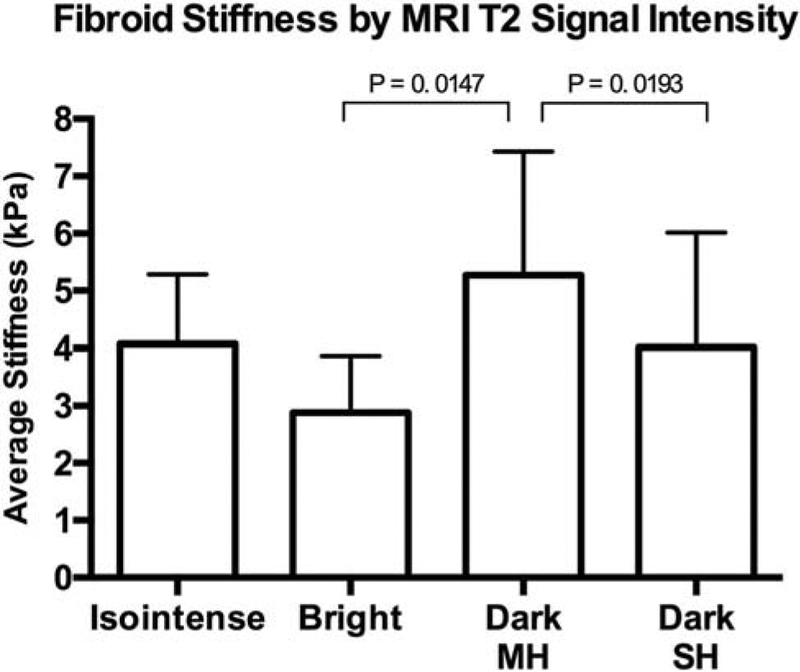

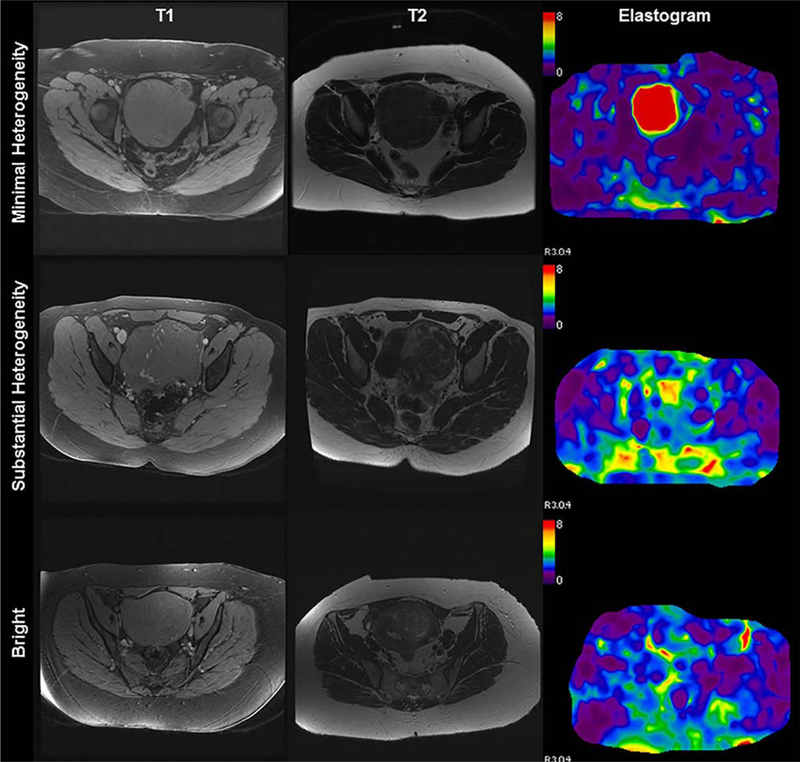

Fibroid appearance was classified by signal intensity into one of four groups in T1 and T2 weighted MRI series. Fibroids in T1 weighted images were identified as isointense (84%), hypointense (4%), hyperintense (4%), or heterogeneous (4%) compared to myometrium. In T2 weighted images, fibroids were identified as dark with minimal heterogeneity (67.6%), dark with substantial heterogeneity (19.6%), isointense (6.9%), or bright (5.9%) signal intensity. Analysis of T2 signal characterization vs. stiffness demonstrated that fibroids of bright (high) T2 signal intensity were significantly less stiff than dark, minimally heterogenous fibroids; the difference in mean stiffness between groups was 2.38 kPa (2.88 ± 0.98 kPa vs. 5.27 ±2.16 kPa; p = 0.0147) (Figs. 1, 2). Compared to fibroids of dark (low) T2 signal intensity with minimal heterogeneity, dark heterogeneous fibroids demonstrated less stiffness with increasing heterogeneity (5.27 ± 2.16 kPa vs. 4.01 ± 2.01 kPa; p = 0.0193) (Figs. 1, 2). Mean stiffness of T2 isointense fibroids (4.15 ± 1.29 kPa) was not statistically different from fibroids of any other T2 category (p > 0.05 for all comparisons). Mean fibroid stiffness was also compared with fibroid MRI T1 appearance and gadolinium contrast enhancement separately; stiffness did not significantly vary among differences in T1 appearance or contrast enhancement (data not shown). Furthermore, analysis of stiffness (kPa) by ethnicity showed no significant differences in fibroid stiffness between Caucasian and African-American women (p > 0.05). Additionally, distribution of fibroid T2 appearance by ethnicity showed no significant differences between any of the 4 imaging categories.

Fig. 1.

Fibroid Stiffness by MRI T2 Signal Intensity. Mean fibroid stiffness values plotted against MRI T2 signal intensity; bars represent standard deviation from the mean. T2 signal intensity is classified as isointense, bright, dark with minimal heterogeneity (MH) or dark with substantial heterogeneity (SH). Compared to fibroids appearing dark with minimal heterogeneity (MH), both bright fibroids and those with substantial heterogeneity (SH) are shown to be significantly less stiff.

Fig. 2.

Fibroid appearance on MRI and corresponding MR elastogram. Magnetic resonance elastography of three patients with varying fibroid T2 signal intensity and composite elastogram with color scale representing shear stiffness (kPa). Columns represent axial T1 and T2 weighted images and elastograms of representative patients with fibroids appearing with minimal heterogeneity, substantial heterogeneity, and bright T2 signal intensity (rows).

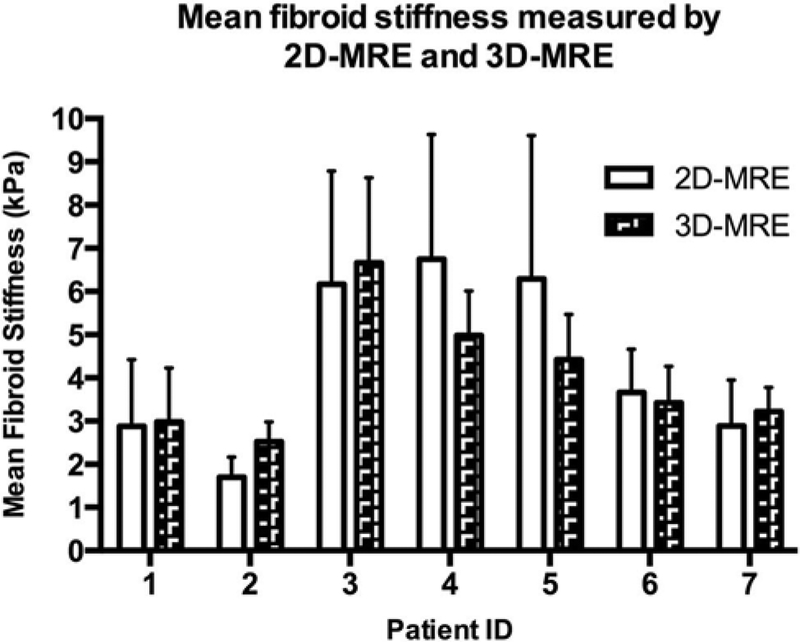

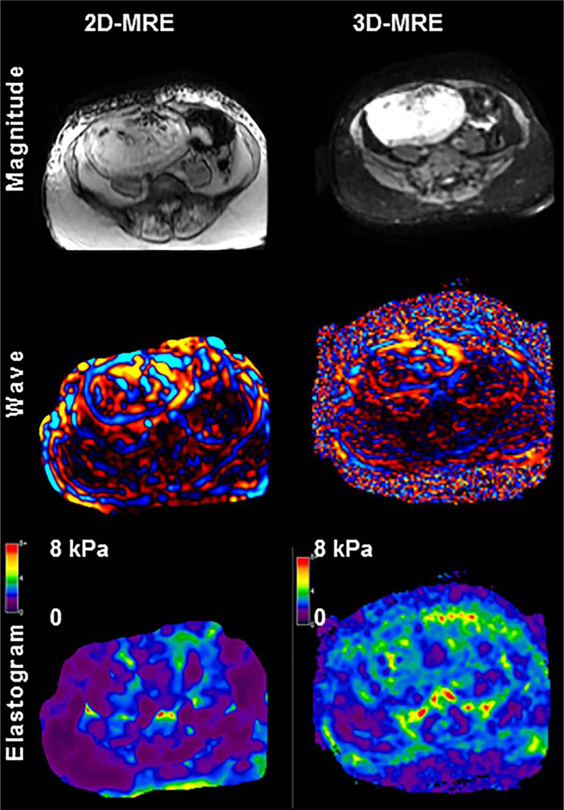

To assess the utility 3D MRE as well as differences in stiffness values obtained via 3D MRE vs. 2D MRE, a subset of 7 patients underwent 3D MRE in addition to 2D MRE. Of the seven fibroids assessed with 3D MRE, four fibroids were intramural, and three were submucosal. All fibroids appeared isointense in T1 images, and in T2 images 5 of 7 appeared dark with minimal heterogeneity, 1 had substantial heterogeneity, and 1 was T2 bright. Comparison of stiffness values obtained by 3D MRE to 2D MRE showed there was no significant difference between the two forms of data acquisition. Figure 3 displays the average fibroid stiffness measured by both 2D MRE and 3D MRE and Fig. 4 shows a slice-matched example of 3D MRE alongside 2D MRE.

Fig. 3.

2D-MRE- vs. 3D-MRE-derived stiffness values. Stiffness (kPa) of uterine fibroids measured by 2D MRE and 3D MRE. Data are representative of mean and standard deviation for seven patients.

Fig. 4.

Representative images of 2D MRE and 3D MRE in a selected uterine fibroid. Comparison magnitude, wave, and elastogram images are displayed with no significant visual differences between 2D MRE and 3D MRE.

Discussion

MRE has previously been shown to be a feasible mechanism for measuring fibroid stiffness, showing wide ranges in stiffness between lesions; however, the clinical utility of fibroid stiffness values in conjunction with clinical imaging has yet to be determined [22], Here we observed a significant inverse correlation between high T2 signal intensity fibroids and stiffness, such that higher intensity fibroids have lower stiffness values compared to fibroids with low and homogenous signal intensity. Of interest, clinical studies have shown that fibroids of high T2 signal intensity tend to be less stiff, and typically respond less favorably to focused ultrasound ablation than those with low T2 signal [8, 9], This finding is consistent with data showing that when MRgFUS is used as a palliative treatment for bone metastases, the stiff cortical bone acts to absorb the majority of the FUS energy [23, 24], Taken together, the findings of these studies suggest that the limitations to FUS treatment for high T2 signal intensity fibroids may in part be due to the mechanical stiffness of the fibroid. Ultimately, better characterization of the fibroid will result in improved ability to predict treatment success and overall deliver better patient care.

Inherent variability in fibroid stiffness can be attributed to differences in fibroid cellularity, collagen content, water content, and presence of degenerative or necrotic tissue. In T2 images, fibroids of high T2 signal intensity can suggest greater water content, lower collagen content, increased cellularity, degeneration, or potential malignancy [25–29], Due to the overlap in imaging characteristics between benign high T2 signal fibroids and uterine sarcoma, lesions of high T2 signal are assessed with more scrutiny and additional diagnostic imaging techniques are needed. While our study did not address differences in leiomyoma and uterine sarcoma, this study further delineated the differences in fibroid mechanical stiffness showing there are clear trends between stiffness and T2 MRI appearance. Future studies using MRE to characterize and differentiate uterine tumors are essential to better understand the relationship between fibroid stiffness, MRI appearance, and potential malignancy.

For the subset of seven patients who underwent both 2D MRE and 3D MRE, there was no significant difference in stiffness values obtained via 2D MRE compared to 3D MRE. 3D-MRE stiffness values trended toward lower values in standard deviation compared to 2DMRE-derived values, though the relationship was not statistically significant. 2D MRE tends to overestimate fibroid stiffness because it is unable to correct the bias caused by potential oblique wave propagations. Smaller standard deviations in mean 3D-MRE stiffness values were likely a result of a more accurate fibroid characterization using wave information collected at 3 polarizations of wave displacement and 3 dimensions of wave propagation.

This study is limited by the relatively low frequency of fibroids appearing with high T2 signal intensity. Moving forward, the practical use of MRE for uterine fibroids will rely heavily on differentiation of mechanical stiffness for different fibroid sub-types as well as against other uterine lesions. While 2D MRE was primarily used in this study to obtain stiffness values, additional studies may consider using primarily 3D MRE to provide more detailed representation of the fibroid’s overall physiological mechanics. Additionally, the scope of the current study was primarily to examine MRE with T1, T2 weighted imaging, as well as contrast enhancement. Future studies will seek to add other specialized imaging parameters to further assess the role of MRE in fibroid evaluation especially as related to diffusion-weighted imaging. Other limitations of the current study relate to the relative homogeneity of the study with 80% Caucasian and 11% African American. Future studies would seek to increase enrollment with better diversity.

The utility of MRE in diagnosis of uterine abnormalities may lend compelling data regarding predicted treatment success, specifically for fibroids of high T2 signal intensity and lower stiffness values. Additionally, with further characterization of cellular fibroids and future characterization of leiomyosarcoma, MRE may provide valuable insight into the suspected mechanical differences between the two lesions. The differentiation of leiomyoma vs. leiomyosarcoma is difficult at best. However, various articles have proposed T2 imaging characteristics, gadolinium enhancement characteristics, or diffusion imaging characteristics may be useful, but no single metric is good enough. Furthermore, another article proposed using multiple parametric analysis coupled with some clinical information for a potential classification scheme. Given the overall difficulty with this imaging distinction, a multiparametric approach will likely be the best answer. MRE may be another possible imaging parameter to add into the analysis. Finally, fibroid stiffness may impact how easily a fibroid can be surgically removed. A recent study on brain lesions showed that preoperative tumor MRE may be able to find firm tumors that may require special care in surgical planning or tumor removal, suggesting a role for fibroid MRE in surgical planning as well [30], Taken together, MRE has expansive potential for clinical use in the characterization of uterine fibroids in conjunction with typical imaging sequences and contrast enhancement characteristics which are normally obtained in imaging evaluation. With further refinement and study, MRE could become a valuable companion in the diagnosis of gynecologic lesions, selection of appropriate treatment, and potential to aid in the prediction of treatment success.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest Danielle E. Jondal, Jin Wang, Jun Chen, Krzysztof R. Gorny, Joel Felmlee and Richard Ehman have nothing to disclose. Gina Hesly reports grants from Insightec, outside the submitted work. Shannon Laughlin-Tommaso reports grants from InSightec Ltd (Israel), outside the submitted work. Elizabeth A. Stewart is supported by RC1HD063312 and R01HD060503 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. Elizabeth A. Stewart also reports personal fees from AbbVie, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, personal fees from Gynesonics, personal fees from Astellas Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Welltwigs, personal fees from Viteava Pharmaceuticals, and personal fees from Allergan, outside the submitted work; In addition, Elizabeth A. Stewart has a patent Methods and Compounds for Treatment of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. US 6440445 issued to none. David A. Woodrum has an NIH grant, “Regulation of molecular thermal ablative resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Funded by National Cancer Institute. (R01 CA 177686).” Personnel funded by this grant helped with the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dixon D, Parrott EC, Segars JH, Olden K, Pinn VW (2006) The second National Institutes of Health International Congress on advances in uterine leiomyoma research: conference summary and future recommendations. Fertil Steril 86(4):800–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baird DD, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM (2003) High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol 188(1):100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okolo S (2008) Incidence, aetiology and epidemiology of uterine fibroids. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 22(4):571–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker CL, Stewart EA (2005) Uterine fibroids: the elephant in the room. Science 308(5728): 1589–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart EA (2015) Clinical practice. Uterine fibroids. N Engl J Med 372(17):1646–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachmann G (2006) Expanding treatment options for women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas: timely medical breakthroughs. Fertil Steril 85(1):46–47 (discussion 48–50) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stewart EA, Rabinovici J, Tempany CM, et al. (2006) Clinical outcomes of focused ultrasound surgery for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Fertil Steril 85(1):22–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorny KR, Borah BJ, Brown DL, et al. (2014) Incidence of additional treatments in women treated with MR-guided focused US for symptomatic uterine fibroids: review of 138 patients with an average follow-up of 2.8 years. J Vase Interv Radiol 25(10):1506–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park H, Yoon SW, Sokolov A (2015) Scaled signal intensity of uterine fibroids based on T2-weighted MR images: a potential objective method to determine the suitability for magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery of uterine fibroids. Eur Radiol 25:3455–3458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers R, Norian J, Malik M, et al. (2008) Mechanical homeostasis is altered in uterine leiomyoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198(4):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leppert PC, Baginski T, Prupas C, et al. (2004) Comparative ultrastructure of collagen fibrils in uterine leiomyomas and normal myometrium. Fertil Steril 82(Suppl 3): 1182–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norian JM, Owen CM, Taboas J, et al. (2012) Characterization of tissue biomechanics and mechanical signaling in uterine leiomyoma. Matrix Biol 31(1):57–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariappan YK, Glaser KJ, Ehman RL (2010) Magnetic resonance elastography: a review. Clin Anat 23(5):497–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Godfrey EM, Mannelli L, Griffin N, Lomas DJ (2013) Magnetic resonance elastography in the diagnosis of hepatic fibrosis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 34(1):81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthupillai R, Lomas DJ, Rossman PJ, et al. (1995) Magnetic resonance elastography by direct visualization of propagating acoustic strain waves. Science 269(5232):1854–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huwart L, Sempoux C, Vicaut E, et al. (2008) Magnetic resonance elastography for the noninvasive staging of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 135(1):32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun J, Hynynen K (1999) The potential of transskull ultrasound therapy and surgery using the maximum available skull surface area. J Acoust Soc Am 105(4):2519–2527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun LT, Ning CP, Liu YJ, et al. (2012) Is transvaginal elastography useful in pre-operative diagnosis of cervical cancer? Eur J Radiol 81(8):e888–e892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bercoff J, Chaffai S, Tanter M, et al. (2003) In vivo breast tumor detection using transient elastography. Ultrasound Med Biol 29(10):1387–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sandrin L, Fourquet B, Hasquenoph JM, et al. (2003) Transient elastography: a new noninvasive method for assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 29(12):1705–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziol M, Handra-Luca A, Kettaneh A, et al. (2005) Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis by measurement of stiffness in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 41(1):48–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart EA, Taran FA, Chen J, et al. (2011) Magnetic resonance elastography of uterine leiomyomas: a feasibility study. Fertil Steril 95(1):281–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Napoli A, Anzidei M, Marincola BC, et al. (2013) MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound for treatment of bone metastasis. Radiographics 33(6):1555–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kurup AN, Callstrom MR (2010) Ablation of skeletal metastases: current status. J Vase Interv Radiol 21(8 Suppl):S242–S250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudderuddin S, Helbren E, Telesca M, Williamson R, Rockall A (2014) MRI appearances of benign uterine disease. Clin Radiol 69(11):1095–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ueda H, Togashi K, Konishi I, et al. (1999) Unusual appearances of uterine leiomyomas: MR imaging findings and their histopathologic backgrounds. Radiographics 19(Spec No):S131–S145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamai K, Koyama T, Saga T, et al. (2008) The utility of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for differentiating uterine sarcomas from benign leiomyomas. Eur Radiol 18(4):723–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sahdev A, Sohaib SA, Jacobs I, et al. (2001) MR imaging of uterine sarcomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177(6):1307–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka YO, Nishida M, Tsunoda H, Okamoto Y, Yoshikawa H (2004) Smooth muscle tumors of uncertain malignant potential and leiomyosarcomas of the uterus: MR findings. J Magn Reson Imaging 20(6):998–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakai N, Takehara Y, Yamashita S, et al. (2016) Shear stiffness of 4 common intracranial tumors measured using mr elastography: comparison with intraoperative consistency grading. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 37:1851–1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]