Abstract

Objectives

To summarise treatment success rate (TSR) among adult bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis (BC-PTB) patients in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

Design

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Google Scholar and Web of Science electronic databases for eligible studies published in the decade between 1 July 2008 and 30 June 2018. Two independent reviewers extracted data and disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer. We used random-effects model to pool TSR in Stata V.15, and presented results in a forest plot with 95% CIs and predictive intervals. We assessed heterogeneity with Cochrane’s (Q) test and quantified with I-squared values. We checked publication bias with funnel plots and Egger’s test. We performed subgroup, meta-regression, sensitivity and cumulative meta-analyses.

Setting

SSA.

Participants

Adults 15 years and older, new and retreatment BC-PTB patients.

Outcomes

TSR measured as the proportion of smear-positive TB cases registered under directly observed therapy in a given year that successfully completed treatment, either with bacteriologic evidence of success (cured) or without (treatment completed).

Results

31 studies (2 cross-sectional, 1 case–control, 17 retrospective cohort, 6 prospective cohort and 5 randomised controlled trials) involving 18 194 participants were meta-analysed. 28 of the studies had good quality data. Egger’s test indicated no publication bias, rather small study effect. The pooled TSR was 76.2% (95% CI 72.5% to 79.8%; 95% prediction interval, 50.0% to 90.0%, I2 statistics=96.9%). No single study influenced the meta-analytical results or conclusions. Between 2008 and 2018, a gradual but steady decline in TSR occurred in SSA but without statistically significant time trend variation (p=0.444). The optimum TSR of 90% was not achieved.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, TSR was heterogeneous and suboptimal in SSA, suggesting context and country-specific strategies are needed to end the TB epidemic.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42018099151.

Keywords: bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis, drug susceptible tuberculosis, smear positive tuberculosis, sub-Sahara Africa, treatment success rate, tuberculosis cure rate

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First systematic review and meta-analysis of tuberculosis treatment success rate (TSR) in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

The methodological design and statistical analyses are sound and robust.

Our results will inform public health interventions and policy for improving TSR across tuberculosis programme in SSA.

Absence of data on TSR for paediatric and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is a limitation.

Introduction

Worldwide, millions of people continue to fall sick and die from tuberculosis (TB),1 a preventable and curable infectious disease. To date, TB remains 1 of the top 10 causes of death,2 and the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent,3 ranking above HIV/AIDS. The 2018 global TB report indicates that 10 million people developed TB disease in 2017.4 Of these, almost 2 million died with 1.3 million of them HIV negative and 0.3 million HIV positive.4 Early diagnosis and successful treatment of TB disease are critical5 in reducing deaths, reducing transmission, preventing emergence of drug resistance, relapse and other complications.6 Data suggest that early diagnosis and treatment of TB prevented 54 million deaths between 2000 and 2016.7 WHO recommends that at least 90% treatment success rate (TSR) for all persons diagnosed with TB and initiated on TB treatment services.8 Despite this recommendation, substantial shortfalls in TB treatment success are common. The latest global TB treatment outcome data for new bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB (BC-PTB) cases indicates a global fall in TSR from 86% in 2014 to 83% in 2017.9 Relatedly, in 2017, only 8 of the 30 high TB burden countries achieved 90% TSR,9 a desired target for ending the global TB epidemic.10

Sub-Saharan African (SSA) region carries the largest burden of TB disease relative to other WHO regions.11 Sixteen of the 30 high TB burden countries are in SSA,12 a region where universal health coverage and social protection for TB stands at 52%, and 46% of TB programme are not funded.4 In addition, epidemiological studies show varying rates of treatment success across TB programme. For instance, studies show TSR of 82.2%13 and 80%14 in South Africa; 90.1%15 and 86.8%16 in Ethiopia; 39%17 in Uganda; 70% in Zimbabwe18 and 57.7%19 in Nigeria.

Despite the observed variations in TSR, SSA presently lacks pooled data on TSR for adult BC-PTB patients. This may hinder TB programme, healthcare managers and policy-makers, and healthcare practitioners from synthesising the variation in TSR, designing effective strategies for reducing TB morbidity and mortality, improving TB treatment outcomes and ending the global TB epidemic. We hence conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to summarise and synthesise a decade of data for TSR among adult (≥15 years of age) BC-PTB patients in SSA.

Methods and analysis

Study design

We used a systematic review and meta-analysis study design to summarise observational and interventional studies published in a decade, from 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2018. We reported the results in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses Protocol (PRISMA)20 21 and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology22 guidelines. We registered the protocol to a platform for the international registration of prospective systematic reviews.23 24 The detailed protocol has been published elsewhere.25 We used WHO standard definitions for TB cases and TB treatment outcomes (table 1).

Table 1.

WHO standard definitions

| Bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB | A patient with TB with a biological specimen that is positive on smear microscopy, culture or molecular test like GeneXpert. |

| Clinically diagnosed pulmonary TB | Patient who does not fulfil the criteria for bacteriological confirmation but has been diagnosed with active TB by a clinician or any other medical practitioner who has prescribed the patient a full course of anti-TB treatment. This also includes X-ray abnormalities or suggestive histology and EPTB cases without laboratory confirmation. |

| Cure | A patient with PTB with bacteriologically confirmed TB at the beginning of treatment, who is smear or culture negative in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion. |

| Died | A patient with TB who dies for any reason before starting or during treatment. |

| Extra pulmonary TB (EPTB) | Any bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed TB case involving organs other than the lungs, such as pleura, lymph nodes, abdomen, genitourinary tract, skin, joints and bones, and meninges among others. |

| HIV positive patient with TB | A bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed TB case who is HIV positive at the time of TB diagnosis or any other evidence of enrolment into HIV care, such as enrolment into pre-ART register or in ART register once ART has been started. |

| Lost to follow-up | Patients with TB who have previously been treated for TB and were declared lost to follow-up at the end of their most recent course of treatment (These were previously known as treatment after default patients). |

| New TB case | A patient with TB who has never had treatment for TB, or had been on anti-TB treatment for less than 4 weeks in the past. |

| Pulmonary TB | Refers to any bacteriologically confirmed or clinically diagnosed case of TB involving the lung parenchyma or the tracheobronchial tree. This also includes miliary TB. Patients with both PTB and EPTB are classified as PTB. |

| Retreatment TB case | These are patients with TB who have relapsed after, defaulted during or failed on first-line treatment. |

| TB relapse | Patient who has previously been treated for TB, was declared cured or treatment completed at the end of their most recent course of treatment, and is now diagnosed with a recurrent episode of TB (either a true relapse or a new episode of TB caused by reinfection). |

| Treatment completed | A patient with TB who completed treatment without evidence of failure but with no record to show that sputum smear or culture results in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion were negative, either because tests were not performed, or results were unavailable. |

| Treatment failed | A patient whose sputum smear or culture is positive at month 5 or later during treatment. |

| Treatment success rate | Proportion of new smear-positive TB cases registered under directly observed therapy in a given year that successfully completed treatment, whether with bacteriologic evidence of success (cured) or without (treatment completed). |

ART, anti-retroviral therapy; TB, tuberculosis.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were considered to be eligible based on: (1) types of study designs: observational (cross-sectional, case–control, prospective and retrospective cohorts) and interventional (randomised controlled trials (RCTs)) epidemiological studies; (2) categories of participants: adults 15 years and older, new and retreatment BC-PTB patients; (3) types of interventions: studies in which participants received either the 6 months anti-TB regimen that consisted of rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z) and ethambutol (E) (2RHZE/4RH) or the 8 months anti-TB regimen (2RHZE/6HE) and studies performed on adult retreatment BC-PTB cases treated with the 8 months anti-TB regimen that contained Streptomycin(S) (2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE); (4) outcomes considered: studies that clearly reported cure and TSRs for new and retreatment BC-PTB patients; (5) period: studies published between 1 July 2008 and 30 June 2018. We chose this time frame for the convenience and on the basis of sufficiency for a demonstrable trend of events.

We excluded: (1) study designs: systematic reviews and meta-analyses; (2) participants: studies that involved patients below 15 years of age, extrapulmonary, clinically diagnosed and multidrug-resistant patients with TB; (3) outcome: studies with unclearly reported treatment outcomes, precisely cure rates and TSR (or outcomes reported contrary to WHO standard definitions) and (4) context: studies that were conducted outside SSA.

Search strategy, searching sources and study selection

We developed a search strategy using key concepts in the research question. We used the search term ‘(Tuberculosis) AND (Treatment AND outcome OR (Successful AND Unsuccessful AND outcome))’. Online supplementary table 1 shows the full electronic search strategy for MEDLINE through PubMed. Details of the search strategy have been reported elsewhere.25 Three reviewers (JI, FB and RS) piloted the search strategy in PubMed between 2 April 2018 and 29 June 2018, and between 2 July 2018 and 30 November 2018, two independent reviewers (JI and RS) searched MEDLINE through PubMed, EMBASE, Google Scholar and Web of Science electronic databases for eligible studies. We exported all retrieved citations in EndNote and removed duplicated citations. The reviewers screened the remaining citations by titles and abstracts, and excluded those found ineligible. Full-text articles of eligible citations were retrieved and read to ascertain their suitability before the data were extracted.

bmjopen-2019-029400supp001.pdf (34.7KB, pdf)

The reviewers also performed a hand search on the reference lists of selected articles in order to include studies that were not identified by the search strategy. The reviewers deliberately searched the International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease database and the websites of WHO and the World Bank for eligible studies. Experts in TB care and research were also consulted for additional research papers. For grey literature, the reviewers searched LILACS, OpenGrey, dissertations/thesis and reports. In each electronic database, RS used an iterative process to refine the search strategy and to incorporate new search terms. The search process was presented in a PRISMA flow chart.

Data extraction and data items

Two independent reviewers (JI and DS) extracted data with a standardised data abstraction form that was developed according to the sequence of variables required from primary studies. Disagreements in data abstraction were resolved by a third independent reviewer, FB. Data were extracted on the following items: author’s first name, publication date, location (country in which the research was conducted), study design (cross-sectional, case–control, prospective and retrospective cohort, and interventional studies), sample size, HIV serostatus (HIV positive and HIV negative), TB treatment regimen (2RHZE/4RH or 2RHZE/6HE (category I), and 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE (Category II), type of patients with TB (new or retreatment TB cases) and TB treatment outcomes (cured, treatment completed, successfully treated, died, defaulted and failed treatment).

In studies that compared TSR in two or more arms, each study arm was considered as a single study and data were extracted separately from each arm to obtain a single outcome measure.

Level of agreement between reviewers

The degree of agreement between the two independent data extractors (JI and DS) was computed with kappa statistics to indicate difference between observed and expected agreements.26 The kappa value was 87.0%, suggesting almost perfect agreement.

Handling of missing data

To obtain missing outcome data, we contacted and requested first authors through electronic mails to provide missing outcome data, performed sensitivity analysis to assess the robustness of meta-analytical results, and discussed the potential impact of missing data on the review findings.27 No missing data were imputed as it is not recommended in meta-analysis.28

Data processing and quality assessment

Extracted data were entered in Epi-Data V.3.1 (Epi-Data Association, Odense, Denmark),29 with quality control measures (skipping, alerts, range and legal values) to ensure data quality. Two reviewers (JI and DS) assessed the quality of data in the included studies using the National Institute of Health (NIH) quality assessment tools.30 31 We preferred the NIH tool because it is comprehensive for an exhaustive assessment of data quality. We rated the overall quality of included studies as good, fair and poor, and incorporated them in the meta-analysis results.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was TSR, defined as the proportion of new and retreatment smear-positive TB cases registered under directly observed therapy-short course (DOTs) in a given year that successfully completed treatment, with (cured) or without (treatment completed) bacteriologic evidence of success among all who were started on TB treatment. Other treatment outcomes included rates of failure, lost to follow-up (LTFU), death and transfer out.

Statistical analysis

Pooled TSR and its prediction interval

Data were analysed in Stata V.15.1 (StataCorp).32 We presented data from included studies in an evidence table and summarised them with descriptive statistics of frequencies and percentages. The outcome measure, TSR, was computed with Metaprop, a Stata command for meta-analysis of proportions. Metaprop allows the inclusion of studies with extreme proportions (equal to 0 or 100%) and avoids CIs surpassing the 0 to 1 range, where normal approximation procedures breaks down. We achieved this by allowing Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation to stabilise variances.33 The pooled TSR was computed with corresponding 95% CI using the Wald method executed with the cimethod (score) Stata command. We generated a forest plot to graphically summarise individual and pooled TSR with 95% CI, the author’s name, publication year and study weights. We also computed prediction interval (PI) for the pooled TSR to reflect its variation in different settings, including the direction of evidence in future studies,34 assuming true effect sizes are normally distributed.

Subgroup analysis

We performed subgroup TSR analysis based on several study characteristics: HIV serostatus (HIV positive, HIV negative or both HIV-positive and negative patients with TB), type of BC-PTB patient (new, retreatment or both new and retreatment), SSA region (Southern, Eastern and Western Africa), study designs (cross-sectional, case–control, cohort and RCT), interventional versus observational studies, study setting (rural, urban and both rural and urban), treatment category (category I, II and both I and II), and the recent United Nations Development Program Human Development Index (HDI) for included countries (very high, high, medium or low).

Testing for heterogeneity and investigation of sources

We assessed heterogeneity between primary studies with Cochran’s (Q) test and quantified with I-squared statistic. A p<0.1 was considered suggestive of statistically significant heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was categorised as low, moderate and high when the values were below 25%, between 25% and 75% and above 75%, respectively.35 We used the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model to pool TSR because studies were anticipated to heterogeneous. We investigated sources of heterogeneity with random-effects univariate meta-regression analysis based on primary study characteristics: study design and setting, publication year, participants’ residence and TB regimen.

The univariate meta-regression analysis was weighted to account for both within‐study variances of treatment effects and residual between‐study heterogeneity (heterogeneity not explained by covariates in the regression).36

Assessment of publication bias

Publication bias, the tendency to publish studies with beneficial outcome or studies that show statistically significant findings,37 was assessed with a funnel plot. Based on the shape of the graph, a symmetrical graph was interpreted suggestive of no publication bias and vice versa.38 39 We performed a contour-enhanced funnel plot to distinguish between publication bias and other causes of funnel plot asymmetry like genuine heterogeneity between small and large studies (small study effect), and differences in baseline characteristics between study participants.40 We used Egger’s weighted regression to test for publication bias, with p<0.1 considered indicative of statistically significant publication bias.38

Cumulative meta-analysis

To determine the 10-year time trends in TSR across SSA, a cumulative meta-analysis was performed. Here, we performed an updated meta-analysis every time a new study appeared, which is critical in evaluating the results of primary studies in a continuum. In the analysis, one primary study was added at a time according to publication date and the results were summarised until all primary studies were added.41 Hence, we obtained trends in the evolution of TSR and assessed the impact of a specific study on the overall conclusion.42

Sensitivity analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the extent to which the meta-analytical results and conclusions may be altered by changes in analysis approach.27 This was critical in assessing the robustness of study conclusion and the impact of methodological quality, sample size and analysis methods on the overall meta-analytical results. In particular, we used the Leave-one-out Jackknife sensitivity analysis,43 where one primary study was excluded at a time and the new pooled TSR was compared with the original TSR. When the new pooled TSR was outside the 95% CI of the original pooled TSR, we concluded that the excluded study had an influential effect in the study, and consequently excluded it from the final analysis.

Post hoc protocol improvements

We noted the NIH tool was appropriate for assessing internal validity of included studies. Second, the NIH tool best determines the extent to which reported study results are attributable to the exposure being evaluated and not the flaws in study design or conduct. We, therefore, adopted three risk assessment tools: (1) the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)44 for assessing the risk of bias in cohort and case–control studies.

The NOS had three domains: (1) selection domain assessed how exposed and unexposed groups in cohort studies, or cases and controls in case–control studies were selected; (2) comparability domain assessed how the exposed and unexposed groups in cohort studies, or cases and controls in case–control studies were compared and (3) ascertainment domain assessed how outcomes in cohort studies, or exposures in case–control studies were measured. We added the scores on the three domains and categorised as 0–2, 3–4 and 5–7 to indicate low, moderate and high-quality study, respectively; (2) For cross-sectional studies, we used a 9-item quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies adopted from Hoy et al.45 Here, we added the scores and classified the grades as 0–3, 4–6 and 7–9 to indicate low, moderate and high risk of bias, respectively (3) For RCTs, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to evaluate the quality of studies as high, low or unclear for individual elements based on five domains: selection, performance, attrition, reporting and other.46

Human subject issues

There was no contact with human subjects or individual-level data in this study. There was no involvement of human subject participants.

Patient and public involvement

We did not involve patients in the development of the research question, outcome measure or the design of the study.

Results

Study selection

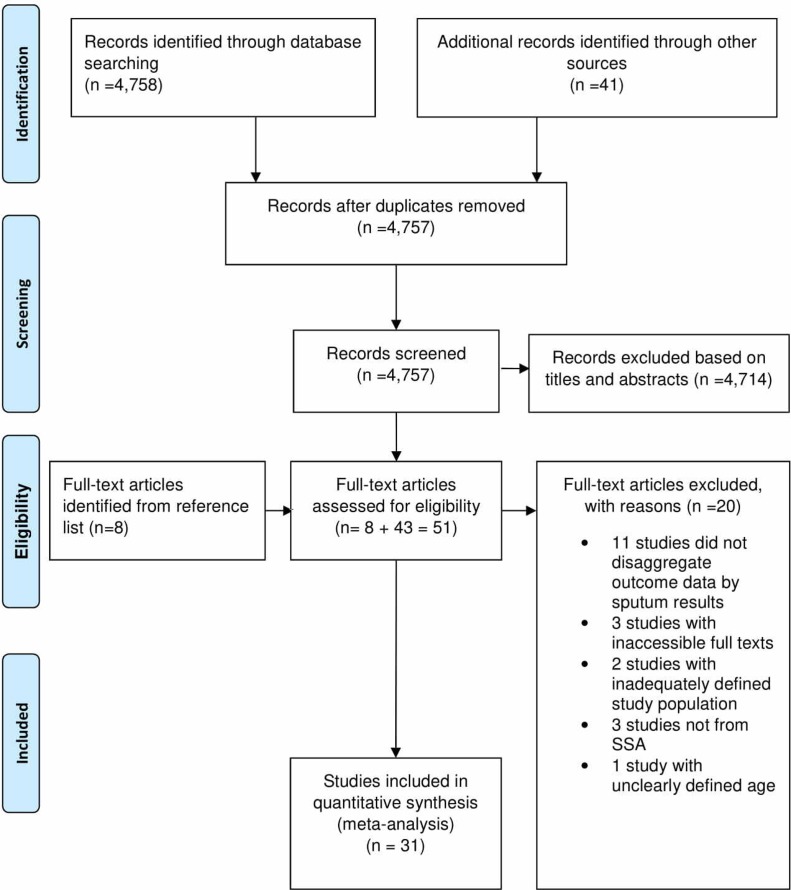

We identified 4779 articles in our search and 4758 were from electronic databases and 41 from other sources. In addition, we identified eight full-text articles from the reference lists of eligible studies (figure 1) bringing the total to 4807. Of these, we excluded 4756 articles: 4714 were found irrelevant after screening the titles and abstracts while 42 were duplicates. Fifty-one full-text articles were, therefore, assessed for eligibility, and 20 were excluded with reasons: 11 did not disaggregate the outcome data according to sputum smear test results, 3 had inaccessible full texts, 2 had inadequately defined study population, 3 were not from SSA and 1 had unclearly defined age of participants (figure 1). Overall, 31 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart showing identification and selection of studies. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa.

Study characteristics

We present the characteristics of the 31 studies included in this meta-analysis in table 2. The studies were from seven countries within SSA (11 from Ethiopia, 9 from Nigeria, 5 from Uganda, 2 from Zimbabwe and 1 each from Malawi and South Africa). Geographically, 21 (67.7%) studies were from Eastern Africa, 9 (29.0%) from Western Africa and only 1 (3.2%) was from Southern Africa and none from Central Africa. Thirty (96.8%) of the 31 studies were from countries with low HDI. Of the 31 studies, 24 (77.4%) included new BC-PTB patients, 3 (9.7%) included retreatment BC-PTB patients, while 4 (12.9%) included both new and retreatment BC-PTB patients.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author and publication year | Country | Study design | Study setting | Type of patient | Age category (years) | Sex | Anti-TB regimen | No of participants | No of participants successfully treated | TSR |

| Adamu,79 2018 | Nigeria | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZE/6EH | 461 | 335 | 72.7 |

| Adane,55 2018 | Ethiopia | PC | Health facility | Both | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 123 | 97 | 78.9 |

| Ali,47 2016 | Ethiopia | CS | Health facility | NBC-PTB | 15–90 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 141 | 121 | 85.8 |

| Alobu,49 2014 | Nigeria | CC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | 15–40 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZE/6EH | 985 | 797 | 80.9 |

| Aseffa,57 2016 | Nigeria | RCT | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 443 | 338 | 76.3 |

| Aseffa,57 2016 | Ethiopia | RCT | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 481 | 363 | 75.5 |

| Babatunde,50 2016 | Nigeria | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥21 | MF | Not reported | 591 | 420 | 71.1 |

| Berhe,48 2012 | Ethiopia | RC | Prison | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 73 | 25 | 88.7 |

| Berihun,53 2018 | Ethiopia | CS | Health facility | Both | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 407 | 361 | |

| Datiko,58 2009 | Ethiopia | RCT | Community | NBC-PTB | 15–54 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 285 | 250 | 87.7 |

| Egwaga,56 2009 | Tanzania | PC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥25 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 1029 | 774 | 75.2 |

| Fatiregun,80 2009 | Nigeria | PC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 1206 | 912 | 75.6 |

| Gabida,81 2015 | Zimbabwe | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | Not reported | 1061 | 772 | 72.8 |

| Gebreegziabher,62 2016 | Ethiopia | PC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 333 | 315 | |

| Jones-López,82 2011 | Uganda | RC | Health facility | RBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 288 | 222 | 77.1 |

| Teshome Kefale,51 2017 | Ethiopia | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 43 | 18 | 41.9 |

| Ketema,63 2014 | Ethiopia | RC | Health facility and community | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 2226 | 2043 | 91.8 |

| Kirenga,83 2014 | Uganda | PC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 96 | 39 | 40.6 |

| Mafigiri,59 2012 | Uganda | RCT | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 107 | 78 | 72.9 |

| Musaazi,84 2017 | Uganda | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZE/6EH | 305 | 220 | 72.1 |

| Nabukenya-Mudiope,85 2015 | Uganda | RC | Health facility | RBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 360 | 240 | 66.7 |

| Nair,54 2008 | South Africa | RC | Health facility | Both | 17.7–87.7 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 1211 | 784 | 64.7 |

| Ndubuisi,52 2017 | Nigeria | PC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | 15–76 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 213 | 184 | 86.4 |

| Ofoegbu,86 2015 | Nigeria | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | 30–49 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 389 | 256 | 65.8 |

| Tafess,87 2018 | Ethiopia | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥25 | MF | Not reported | 188 | 145 | |

| Takarinda,88 2012 | Zimbabwe | RC | Health facility | RBC-PTB | ≥18 | MF | 2RHZES/1RHZE/5RHE | 225 | 163 | 72.4 |

| Tweya,89 2013 | Malawi | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 2361 | 2041 | 86.4 |

| Ukwaja,90

2015 |

Nigeria | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH and 2RHZE/6EH | 928 | 754 | 81.2 |

| Ukwaja,60

2017 |

Nigeria | RCT | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/4RH | 161 | 130 | 80.7 |

| van den Boogaard,91 2009 | Tanzania | RC | Health facility | Both | ≥15 | MF | 2RHZE/6EH | 1126 | 912 | 81.0 |

| Zenebe,92 2016 | Ethiopia | RC | Health facility | NBC-PTB | ≥15 | MF | Not reported | 348 | 297 | 85.3 |

CC, case–control; CS, cross-sectional study; MF, male and females; NBC-PTB, new bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis patients; PC, prospective cohort study design; RBC-PTB, retreatment bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis patients; RC, retrospective cohort study design; RCT, randomised controlled trial; TB, tuberculosis; TSR, treatment success rate.

The 31 studies had a combined sample size of 18 194 participants, with a range of 43–2361. All these studies reported on the number of participants who were successfully treated. Fourteen (45.2%) studies reported on the number of participants who were cured, with a combined sample size of 8742 participants. Ten (32.2%) studies reported on the number of participants who completed TB treatment with a combined sample size of 1185 participants.

The study designs for these studies are shown in table 2. Here, 26 (83.9%) studies were observational while 5 (16.1%) were interventional. Two (6.4%) studies used a cross-sectional design, 1 (3.2%) used a case–control design, 17 (54.8%) used a retrospective cohort design, 6 (19.3%) used a prospective cohort design and 5 (16.1%) were RCTs. Twenty-eight (90.3%) studies were conducted in a health facility (hospital, health centre and clinic) setting. One study was conducted in three settings namely a prison, community and health facility.

Quality of included studies

Twenty-eight (90.3%) studies had good quality data while three (9.7%) had fair quality data as determined from the NIH quality assessment tool.30 31 One cross-sectional study47 had a score of 1 while the other48 had a score of 2 on the 9-item checklist, suggesting a low risk of bias (see online supplementary table 2). In relation to cohort and case–control studies, the total NOS scores ranged from 5 to 9, signifying included studies were of good quality. A score of 5 was recorded in a case–control49 and a retrospective cohort study,50 a score of 7 was found in one retrospective51 and another prospective cohort study,52 a score of 8 was found in four studies (two prospective cohort53 54 and two retrospective cohort studies,55 56 while each of the remaining 16 studies scored 9 (see online supplementary table 3). With respect to risk of bias in RCTs using the Cochrane’s collaboration tool, we found low risk of bias on the selection domain for the RCTs57–60 except in one RCT60 where it was high (see online supplementary figure 1). Nonetheless, in general, the risk of bias was low on the performance, detection, attrition, reporting and other domains.

bmjopen-2019-029400supp002.pdf (45.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp003.pdf (47.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp005.pdf (55.2KB, pdf)

Study outcomes

Primary outcome: pooled and predictive TSRs

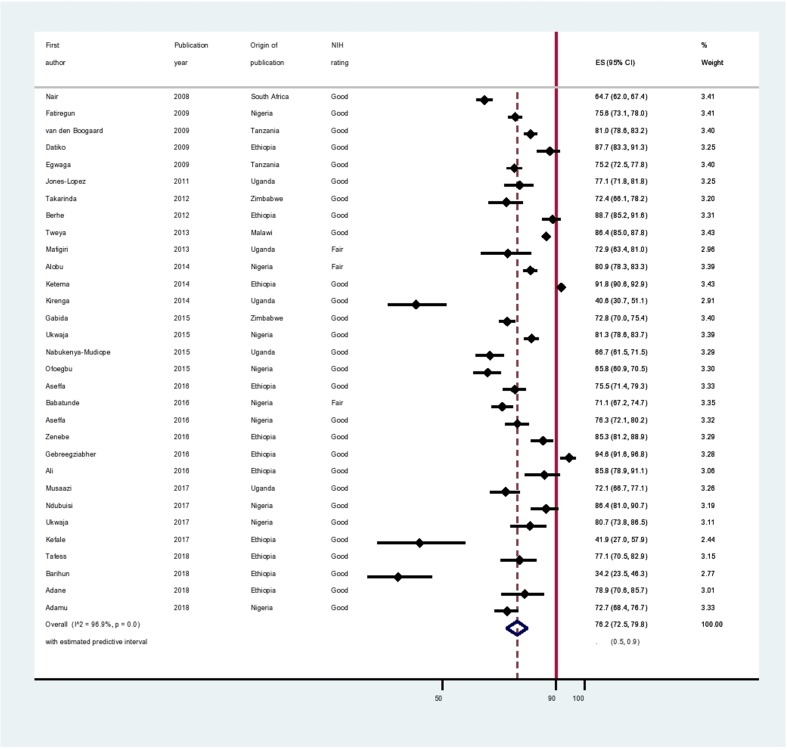

The pooled TSR was 76.2% (95% CI 72.5% to 79.8%; 95% PI 50.0% to 90.0%) (figure 2). The pooled cure rate was 64.5% (95% CI 55.1% to 73.3%; 95% PI 30.0% to 90.0%) obtained from 14 studies that reported the number of participants who were cured. The pooled treatment completion rate was 13.7% (95% CI 7.4% to 21.4%; 95% PI, 0.0% to 50.0%) obtained from 10 studies that reported the number of participants who completed TB treatment as the outcome.

Figure 2.

Forest plot. The graph displays individual TSR and 95% CI for each included study, and the pooled TSR for all the 31 studies with corresponding 95% CI and predictive Interval. TSR, treatment success rate.

Other outcomes: unsuccessful treatment outcomes

Fifteen studies reported the number of participants who failed on TB treatment and who were transferred out while 16 studies reported the number of participants who were LTFU and who died during TB treatment. In the 31 studies, 3788 (24.0%; 95% CI 20% to 28%; 95% PI 7% to 47%) participants received treatment without success: 2645 were reported (401 failure, 1111 LTFU, 859 died and 274 transferred out) while 1143 participants were not reported.

Subgroup analyses

The results of the subgroup analysis are shown in table 3. A TSR of 76.8% (95% CI 73.2% to 80.3%) was observed in Western African countries, 76.4% (95% CI 71.5% to 81.0%) in Eastern African countries, and 64.7% (95% CI 62.0% to 67.4%) in a Southern African country. A TSR of 76.3% (95% CI 72.0% to 80.3%) and 76.2% (95% CI 72.5% to 79.8%) were reported in new and retreatment BC-PTB patients, respectively. Regarding study designs, the TSRs are as follows: 88.0% (95% CI 85.2% to 90.6%) in cross-sectional studies, 80.9% (95% CI 78.3% to 83.3%) in a case–control study, 79.0% (95% CI 73.5% to 84.1%) in RCTs, 73.1% (95% CI 67.3% to 78.6%) in retrospective cohort studies and 77.3% (95% CI 67.3% to 86.0%) in prospective cohort studies. When the study designs were grouped into interventional and observational studies, the TSRs were 79.0% (95% CI 73.5% to 84.1%) and 75.7% (95% CI 71.4% to 79.7%), respectively. Other TSRs with respect to study setting, residence, HDI and treatment categories are also shown in table 3. However, certain subgroups had homogeneous TSR (I2 value=0.00%).

Table 3.

Subgroup and heterogeneity analysis of TSR according to study characteristics

| Characteristics | No of studies | No of participants | Pooled TSR (95% CI) | 95% PI for pooled TSR | Percentage weight | Q-test p value | I2 |

| HIV status of patients with TB | 0.346 | ||||||

| Not reported | 5 | 2845 | 77.9 (68.7 to 85.9) | (40.0–100.0) | 16.2 | 96.2 | |

| HIV positive | 4 | 1794 | 70.1 (60.7 to 78.8) | (30.0–100.0) | 12.4 | 92.6 | |

| Both HIV positive and HIV negative | 22 | 13 555 | 77.0 (72.5 to 81.2) | (50.0–90.0) | 71.4 | 97.1 | |

| Type of BC-PTB patients | 0.439 | ||||||

| Both new and retreatment | 4 | 2867 | 78.9 (66.9 to 88.9) | (20.0–100.0) | 13.1 | 97.8 | |

| New | 24 | 14 454 | 76.3 (72.0 to 80.3) | (50.0–90.0) | 77.1 | 96.9 | |

| Retreatment | 4 | 2867 | 76.2 (72.5 to 79.8) | (50.0–90.0) | 9.7 | 0.00 | |

| SSA region | <0.001 | ||||||

| Southern | 1 | 1211 | 64.7 (62.0 to 67.4) | IE | 3.4 | 0.00 | |

| Eastern | 21 | 11 606 | 76.4 (71.5 to 81.0) | (50.0–90.0) | 66.8 | 97.0 | |

| Western | 9 | 5377 | 76.8 (73.2 to 80.3) | (60.0–90.0) | 29.9 | 89.2 | |

| Study design | <0.001 | ||||||

| Cross-sectional | 2 | 548 | 88.0 (85.2 to 90.6) | IE | 6.4 | 0.00 | |

| Case–control | 1 | 985 | 80.9 (78.3 to 83.3) | IE | 3.4 | 0.00 | |

| Retrospective cohort | 17 | 12 184 | 73.1 (67.3 to 78.6) | (50.0–90.0) | 55.1 | 97.9 | |

| Prospective cohort | 6 | 3000 | 77.3 (67.3 to 86.0) | (40.0–100.0) | 19.2 | 96.9 | |

| RCT | 5 | 1477 | 79.0 (73.5 to 84.1) | (50-0–90.0) | 16.0 | 82.8 | |

| Study design category | 0.334 | ||||||

| Observational | 26 | 16 717 | 75.7 (71.4 to 79.7) | (60.0–90.0) | 84.0 | 97.4 | |

| Interventional | 5 | 1477 | 79.0 (73.5 to 84.1) | (60.0–90.0) | 16.0 | 82.8 | |

| Study setting | <0.001 | ||||||

| Health facility | 28 | 15 610 | 76.3 (73.0 to 79.5) | (60.0–90.0) | 90.6 | 96.4 | |

| Prison | 1 | 73 | 34.2 (23.5 to 46.3) | IE | 2.8 | 0.00 | |

| Community | 1 | 285 | 87.7 (83.3 to 91.3) | IE | 3.2 | 0.00 | |

| Health facility and community | 1 | 2226 | 91.8 (90.6 to 92.9) | IE | 3.4 | 0.00 | |

| Residence | <0.001 | ||||||

| Rural | 2 | 633 | 86.4 (83.6 to 89.0) | IE | 6.5 | 0.00 | |

| Semi/periurban | 2 | 320 | 82.3 (77.9 to 86.3) | IE | 6.1 | 0.00 | |

| Urban | 13 | 7495 | 70.6 (64.2 to 76.7) | (40.0–90.0) | 41.4 | 96.8 | |

| Both rural and urban | 14 | 9746 | 78.9 (73.7 to 83.7) | (50.0–100.0) | 45.9 | 97.2 | |

| HDI rating | <0.001 | ||||||

| Low | 30 | 1211 | 76.7 (73.1 to 80.1) | 76.7 (50.0–90.0) | 96.6 | 96.2 | |

| Medium | 1 | 16 983 | 64.7 (62.0 to 67.4) | IE | 3.4 | 0.00 | |

| TB treatment category | 0.629 | ||||||

| Category I and II | 4 | 2867 | 78.9 (66.9) | (20.0–100.0) | 13.1 | 97.8 | |

| Category I | 20 | 12 266 | 76.2 (71.3 to 80.7) | (50.0–90.0) | 63.9 | 97.1 | |

| Category II | 3 | 873 | 72.1 (65.6 to 78.1) | IE | 9.7 | 0.00 | |

| Not reported | 4 | 2188 | 76.7 (70.2 to 82.5) | IE | 13.2 | 90.4 |

IE: 95% PI are inestimable because there are less than three studies.

BC-PTB, bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis; HDI, Human Development Index; IE, inestimable; PI, prediction interval; RCT, randomised controlled trial; SSA, sub-Saharan Africa; TB, tuberculosis; TSR, treatment success rate.

Heterogeneity across studies

Our analysis revealed high heterogeneity among included studies (χ2 (30 df)=968.62; I2=96.9%; p<0.01). We also observed high heterogeneity (I2 values of at least 90%; p<0.01) in subgroup analyses by: HIV status of study participants, type of patient with TB, the region from which the study was performed, study designs, study setting, participants residence, HDI and anti-TB treatment category (table 3).

Univariate meta-regression analysis

We assessed factors associated with changes in TSR and the results are shown in table 4. Univariable meta-regression analysis showed TSR declined with an increase in year with no statistically significant differences or trend between 2008 and 2018. Patients with TB who were treated in the community had a 0.58% (95% CI 0.91% to 0.24%) lower TSR than those treated at health facilities. Besides this, the other study characteristics were not the source of statistical heterogeneity.

Table 4.

Univariate meta-regression analysis involving several study characteristics

| Study characteristics | Univariate meta-regression analysis results | ||

| Coefficients | 95% CI | P value | |

| Publication year (ref: 2008) | |||

| One-year increase | −0.01 | −0.02 to 0.01 | 0.444 |

| Study designs (ref: case–control) | |||

| Cross-sectional | 0.06 | −0.28 to 0.40 | 0.703 |

| Retrospective cohort | −0.09 | −0.37 to 0.20 | 0.536 |

| Prospective cohort | −0.05 | −0.35 to 0.25 | 0.732) |

| RCT | −0.02 | −0.33 to 0.28 | 0.882) |

| Study setting (ref: health facility) | |||

| Prison | −0.16 | −0.39 to 0.06 | 0.154 |

| Community | −0.58 | −0.91 to 0.24 | 0.002 |

| Health facility and community | −0.04 | −0.36 to 0.28 | 0.794 |

| Participant residence (ref: semi/periurban) | |||

| Rural | 0.07 | −0.20 to 0.33 | 0.617 |

| Urban | −0.10 | −0.31 to 0.11 | 0.333 |

| Both rural and urban | −0.02 | −0.23 to 0.18 | 0.836 |

| Category of anti-TB treatment (ref: Category II) |

|||

| Both category I and II | 0.06 | −0.16 to 0.28 | 0.565 |

| Category I | 0.03 | −0.15 to 0.21 | 0.758 |

| Category not reported | 0.04 | −0.17 to 0.26 | 0.678 |

95% CIs in brackets; ref: reference category.

RCT, randomised controlled trial; TB, tuberculosis.

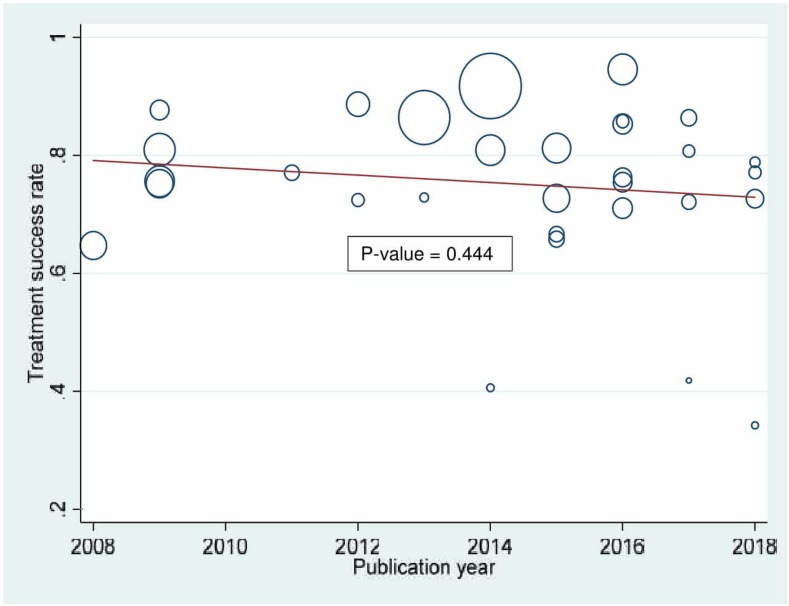

Time trend analysis

The time trend analysis showed a gradual but steady decline in TSR among adult BC-PTB patients in SSA from 2008 to 2018 (figure 3). Nevertheless, we noted no statistically significant time trend variation (p=0.444) over the decade.

Figure 3.

Time trend of treatment success rate in sub Saharan Africa from 2008 to 2018.

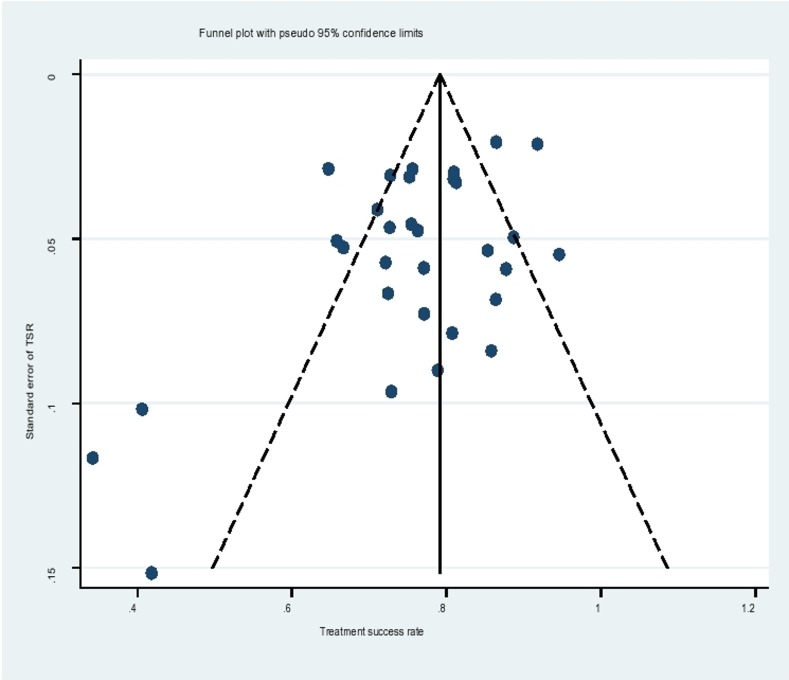

Test for publication bias

The funnel plot for assessment of publication bias was asymmetrical (figure 4), suggesting probable publication bias. A contour-enhanced funnel plot indicated that missing studies were in the region of higher statistical significance (p<0.01), with none missing in the region of low statistical significance (p>0.1). This implied that the asymmetry was not caused by the publication bias, rather by other causes like small study effect sizes and differences in participant characteristics. Egger’s test confirmed the asymmetry, with the intercept deviating significantly from 0 (Egger’s test, p=0.022). Egger’s test showed smaller studies gave different results compared with larger studies since the CI of the intercept did not include the 0 value.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot. The graph displays the relationship between SE of treatment success rate (TSR) against TSR to detect funnel plot asymmetry.

Additional analyses

Sensitivity analysis

We found no single study significantly influenced the overall meta-analytical results (see online supplementary figure 2). This implied the study conclusions are robust, and the meta-analytical results were less affected by the studies’ methodological quality, statistical analysis and sample sizes.

bmjopen-2019-029400supp006.pdf (162.7KB, pdf)

Meta-cumulative analysis

Concerning time trends in TSR within SSA (see online supplementary table 4), TSR improved between 2008 and 2013, dropped between 2014 and 2015, increased between 2016 and 2017, and finally dropped in 2018. Overall, over the past 10 years, none of the countries in SSA achieved WHO recommended TSR of 90%.

bmjopen-2019-029400supp004.pdf (43.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 31 published studies from seven countries, in three regions within SSA found a pooled TSR of 76% among adult BC-PTB patients, which is far below the global TSR of 83%9 and WHO recommended TSR of at least 90%.61 The suboptimal pooled TSR is an indication of generally unsuccessful TB programme in SSA, typically characterised by underperformance. Our results suggest that a sizeable number of BC-PTB patients in SSA enter and exit TB programme without favourable treatment outcomes. Indeed, in the present study, only two studies62 63 showed TSR reaching and/or exceeding the 90% WHO recommended TSR threshold. Since suboptimal TSR is associated with marked TB morbidity and mortality,64 it is not surprising that SSA continues to register the slowest decline in TB incidence rate, the highest annual TB incidence rate of 25%,65 and the highest TB case fatality rate of 20%.1 Even in the 2017 global TB report, the African region had a high TB incidence and mortality rate of 254 (227–284) and 72 (64–81) per 100 000 population, respectively.1 We found a pooled cure rate of 64% that varied from 55% to 73%, which is substantially lower than WHO recommended cure rate of 85%.61 Again, this means increased TB morbidity and mortality within SSA.

In subgroup analysis, a high TSR was reported in cross-sectional and case–control studies than other study designs. Likewise, interventional studies had high TSR than observational studies. These results require cautious interpretations. We think differences in the design and conduct of observational and interventional studies could better explain the results. Interventional studies are usually designed and conducted more rigorously than observational studies.66 In most cases, interventional studies adhere to stringent and intensive methodology compared with observational studies. Unlike observational studies, data generated in interventional studies tends to be more complete and accurate.66 It is, therefore, possible that differences in data integrity could be the plausible reason to explain the varying rates of treatment success across the various study designs.

The pooled TSR was lower in studies conducted on HIV-positive patients with TB; studies that included both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with TB compared with studies that never reported HIV test results. The relationship between TB and HIV is well established.67 HIV weakens the immune system and increases the likelihood of developing opportunistic infections like TB in this case, the progression from latent to active TB, and TB relapse among those successfully treated.

Conversely, TB accelerates HIV progression to full-blown AIDS by increasing viral replication and exacerbates mortality.68 At present, TB is the leading infectious disease killer among people living with HIV.1 Since death is one measure of unfavourable TB treatment outcome, high mortality rate among HIV-positive patients with TB contributes to low TSR. Our finding is consistent with several studies in SSA,19 69–71 where HIV-positive persons registered unsuccessful TB treatment outcomes.

We found better TSR in studies that involved patients with TB of category I and II combined compared with studies that involved either patients with TB of category I or II. The treatment of new BC-PTB patients lasts for 6 months whereas that of retreatment cases lasts for 8 months. In addition, retreatment cases have high pill burden compared with new TB cases. These two factors perhaps explain the observed difference in TSR. Possibly, retreatment TB cases experienced drug fatigue due to high pill burden and longer treatment duration, resulting into compromised treatment adherence. This finding is consistent with an earlier study in Ethiopia where retreatment TB cases had increased likelihood of unsuccessful treatment outcome compared with new TB cases.16 69

Our study indicates BC-PTB patients who were treated in a prison setting had lower TSR than those treated in a health facility or community setting. First, TB control in prison setting presents a special problem for the healthcare system. A systematic review showed that incarcerated populations in several prison systems face several challenges that hinder effective TB control. These challenges among others include insufficient laboratory capacity and diagnostic tools, interrupted supply of medicines, weak integration between civilian and prison TB services, inadequate infection control measures, and low priority for prison healthcare on health policy agenda.72 We hypothesise that the low TSR in prison settings is likely attributable to the stated challenges as well as lack of social support, unsupervised treatment, among others.

The pooled TSR in the present study is less than the 86% reported in a previous systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 studies in Ethiopia.73 However, one should be cautious in comparing our data with that of Ethiopia due to differences in eligibility criteria. Unlike the present study, the study in Ethiopia included extrapulmonary and clinically diagnosed patients with PTB. Second, the Ethiopian meta-analysis only represented data from one country and the results do not adequately represent regional or continental TSR.

In general, without improvements in TSR within SSA, achieving the end TB Strategy targets of reducing TB deaths by 90% and TB incidence by 80% among new TB cases per year by 2030 remains farfetched.10 74

Implications of study findings

Our findings have important implications. In clinical care of patients with TB, health systems need to increase the number and to improve the quality of human resources for health.75 We propose on-job coaching, mentorships and trainings76 on TB management to enhance healthcare provider competence in treating patients with TB thereby improving TB treatment outcomes. Another opportunity for TB knowledge enhancement is continuous medical education sessions which should focus on TB diagnosis, treatment and patient monitoring across health facilities. Task shifting77 from physicians and medical officers to nurses is another option for improving TB treatment outcomes. On the patient side, counselling and health education on the duration of TB treatment, rationale for completing anti-TB treatment, and treatment monitoring is critical.78 In public health, building new tools for evaluating the performance and effectiveness of TB programme and increased funding should be considered.75 In research, rigorous studies are needed on interventions that can improve the effectiveness of TB programme in SSA.

Study strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to summarise TSR among adult BC-PTB patients in SSA. We used a sensitive and specific search strategy, and conducted comprehensive literature review that enabled the retrieval of appropriate published articles for the period under review. Our analysis included most study designs and demonstrated very little, if any publication bias. This makes the results of this meta-analysis more reliable. However, we found a small study effect. The quality of data in the included studies was good. Sensitivity analysis showed the methodological approach, quality of included studies, statistical analysis, results and conclusions are robust. Despite these strengths, several limitations should be considered in interpreting the results. First, this study involved only adult BC-PTB patients. Second, data were from seven countries, three regions (Southern, Eastern and Western), and low and medium HDI countries within SSA. Our findings, therefore, do not apply to children (below 15 years) and patients with other forms of TB (extrapulmonary TB, CD-PTB and MDR-TB). Third, no data were abstracted on DOTs, and therefore, the impact of DOTs on TSR was not evaluated.

Conclusion and recommendations

This systematic review and meta-analysis found relatively low rates of treatment success and cure among adult BC-PTB patients. Both rates are distant from WHO recommended TSR of at least 90% and cure rate of 85%. To reduce TB-related morbidity and mortality, combat the rising threat of MDR-TB, and achieve the goal of ending the global TB epidemic by 2035, urgent interventions are needed to improve the performance of national TB programme in SSA. Successfully tackling TB will likely require concerted and focused efforts by multiple stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the German Academic Exchange Services (DAAD) and the Department of Community Health, Mbarara University of Science and Technology.

Footnotes

Contributors: JI is the first and corresponding author. JI and FB conceived and designed the study. JI, DS and FB acquired the data. JI and FB analysed the data and interpreted the results. JI, DS, RS, IKT and FB drafted the initial and final manuscripts. JI, DS, RS, IKT and FB performed critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not required because the analysis under consideration is from data that already publicly available in published studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1. World Health Organization Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva, Switzerland, 2017: 5-7, 21-22, 63. [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization Tuberculosis, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- 3. World Health Organization Global health estimates 2016: deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2016. Geneva, Swtizerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization Global tuberculosis report 2018. Geneva, Switzerland, 2018: 27–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization TB treatment and care, 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/tb/areas-of-work/treatment/en/

- 6. British HIV Association (BHIVA) Aims of TB treatment, 2019. Available: https://www.bhiva.org/20AimsofTBtreatment

- 7. World Health Organization Joint Initiative "FIND. TREAT. ALL. #ENDTB", 2019. Available: https://www.who.int/tb/joint-initiative/en/

- 8. Stop TB Partnership First Global Plan to End TB Progress Report shows need for huge efforts and scale-up to reach 90-(90)-90 TB targets, 2017. Available: http://www.stoptb.org/news/stories/2017/ns17_060.asp

- 9. Stop TB Partnership 90 (90) 90 The tuberculosis report for heads of state and governments. Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization The end TB strategy: global strategy and targets for tuberculosis prevention, care and control after 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization The state of health in the WHO African region: an analysis of the status of health, health services and health systems in the context of the sustainable development goals, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization Use of high burden country lists for TB by WHO in the post-2015 era. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobson KB, Moll AP, Friedland GH, et al. . Successful tuberculosis treatment outcomes among HIV/TB coinfected patients Down-Referred from a district hospital to primary health clinics in rural South Africa. PLoS One 2015;10:e0127024 10.1371/journal.pone.0127024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Budgell EP, Evans D, Schnippel K, et al. . Outcomes of treatment of drug-susceptible tuberculosis at public sector primary healthcare clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa: a retrospective cohort study. S Afr Med J 2016;106:1002–9. 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i10.10745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Worku S, Derbie A, Mekonnen D, et al. . Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment short-course at Debre Tabor General Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: nine-years retrospective study. Infect Dis Poverty 2018;7 10.1186/s40249-018-0395-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Getnet F, Sileshi H, Seifu W, et al. . Do retreatment tuberculosis patients need special treatment response follow-up beyond the standard regimen? finding of five-year retrospective study in pastoralist setting. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:762 10.1186/s12879-017-2882-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakanwagi-Mukwaya A, Reid AJ, Fujiwara PI, et al. . Characteristics and treatment outcomes of tuberculosis retreatment cases in three regional hospitals, Uganda. Public Health Action 2013;3:149–55. 10.5588/pha.12.0105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Srinath S, et al. . Treatment outcomes of new adult tuberculosis patients in relation to HIV status in Zimbabwe. Public Health Action 2011;1:34–9. 10.5588/pha.11.0001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ukwaja KN, Ifebunandu NA, Osakwe PC, et al. . Tuberculosis treatment outcome and its determinants in a tertiary care setting in south-eastern Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2013;20:125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Izudi J, Semakula D, Sennono R, et al. . Protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment success rate among adult tuberculosis patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PROSPERO 2018;8:e024559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chien PFW, Khan KS, Siassakos D. Registration of systematic reviews: PROSPERO. Int J Obstet Gy 2012;119:903–5. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03242.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Izudi J, Semakula D, Sennono R, et al. . Protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment success rate among adult patients with tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open 2018;8:e024559 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mavridis D, Chaimani A, Efthimiou O, et al. . Addressing missing outcome data in meta-analysis. Evid Based Ment Health 2014;17:85–9. 10.1136/eb-2014-101900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tacconelli E. Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect Dis 2010;10:226 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70065-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lauritsen J, Bruus M. EpiData (version 3) In: A comprehensive tool for validated entry and documentation of data Odense: EpiData Association, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30. National Institutes of Health Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. National heart, lung, and blood Institute, 2014. Available: www. nhlbi. nih. gov/health-pro/guidelines/indevelop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort [Accessed 5 Nov 2015].

- 31. National Institute of Health Study quality assessment tools, 2018. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 32. StataCorp Stata statistical software: release 15. 10 College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, 2017: 733. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Rovers MM, et al. . Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010247 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Green S, Higgins J. Version, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thompson SG, Higgins JPT. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 2002;21:1559–73. 10.1002/sim.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rothstein HR, Sutton AJ, Borenstein M. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment and adjustments. John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Song F, Gilbody S. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. increase in studies of publication bias coincided with increasing use of meta-analysis. BMJ 1998;316:471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Palmer TM, Sutton AJ, Peters JL, et al. . Contour-enhanced funnel plots for meta-analysis. Stata J 2008;8:242–54. 10.1177/1536867X0800800206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lau J, Schmid CH, Chalmers TC. Cumulative meta-analysis of clinical trials builds evidence for exemplary medical care. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:45–57. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00106-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Haidich AB. Meta-analysis in medical research. Hippokratia 2010;14(Suppl 1):29–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Steichen T. METANINF: Stata module to evaluate influence of a single study in meta-analysis estimation, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. . The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;65:934–9. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. . Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ali SA, Mavundla TR, Fantu R, et al. . Outcomes of TB treatment in HIV co-infected TB patients in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional analytic study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:640 10.1186/s12879-016-1967-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Berhe G, Enquselassie F, Aseffa A. Treatment outcome of smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Tigray region, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012;12:537 10.1186/1471-2458-12-537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Alobu I, Oshi DC, Oshi SN, et al. . Profile and determinants of treatment failure among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ebonyi, southeastern Nigeria. Int J Mycobacteriol 2014;3:127–31. 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Babatunde OI, Christiandolus EO, Bismarck EC, et al. . Five years retrospective cohort analysis of treatment outcomes of TB-HIV patients at a PEPFAR/DOTS centre in South Eastern Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 2016;16:655–62. 10.4314/ahs.v16i3.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Teshome Kefale A, Anagaw YK. Outcome of tuberculosis treatment and its predictors among HIV infected patients in Southwest Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med 2017;10:161–9. 10.2147/IJGM.S135305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ndubuisi NO, Azu OR, Oluoha N. Treatment outcomes of new smear positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients under directly observed treatment in Anambra state, Nigeria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Berihun YA, Nguse TM, Gebretekle GB. Prevalence of tuberculosis and treatment outcomes of patients with tuberculosis among inmates in Debrebirhan prison, North Shoa Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2018;28:347–54. 10.4314/ejhs.v28i3.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nair G. A comparison of direct observation of treatment methods used for treating pulmonary tuberculosis in Durban (eThekwini), KwaZulu-Natal, Citeseer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Adane K, Spigt M, Dinant G-J. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and predictors in northern Ethiopian prisons: a five-year retrospective analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2018;18:37 10.1186/s12890-018-0600-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Egwaga S, Mkopi A, Range N, et al. . Patient-centred tuberculosis treatment delivery under programmatic conditions in Tanzania: a cohort study. BMC Med 2009;7:80 10.1186/1741-7015-7-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Aseffa A, Chukwu JN, Vahedi M, et al. . Efficacy and Safety of ‘Fixed Dose’ versus ‘Loose’ Drug Regimens for Treatment of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Two High TB-Burden African Countries: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157434 10.1371/journal.pone.0157434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Datiko DG, Lindtjørn B. Health extension workers improve tuberculosis case detection and treatment success in southern Ethiopia: a community randomized trial. PLoS One 2009;4:e5443 10.1371/journal.pone.0005443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mafigiri DK, McGrath JW, Whalen CC. Task shifting for tuberculosis control: a qualitative study of community-based directly observed therapy in urban Uganda. Glob Public Health 2012;7:270–84. 10.1080/17441692.2011.552067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ukwaja KN, Alobu I, Gidado M, et al. . Economic support intervention improves tuberculosis treatment outcomes in rural Nigeria. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017;21:564–70. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. World Health Organization Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for nationl programmes. World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gebreegziabher SB, Bjune GA, Yimer SA. Total delay is associated with unfavorable treatment outcome among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in West Gojjam zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159579 10.1371/journal.pone.0159579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ketema KH, Raya J, Workineh T, et al. . Does decentralisation of tuberculosis care influence treatment outcomes? The case of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Public Health Action 2014;4:13–17. 10.5588/pha.14.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. WHO Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. Geneva, 2003: 11, 47,53. [Google Scholar]

- 65. World Health Organization Global tuberculosis report 2016. Geneva, Switzerland, 2016: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thiese MS. Observational and interventional study design types; an overview. Biochem Med 2014;24:199–210. 10.11613/BM.2014.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ungvarski PJ, Flaskerud JH. HIV/AIDS: a guide to primary care management. WB Saunders Comp, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Maher D, Harries A, Getahun H. Tuberculosis and HIV interaction in sub-Saharan Africa: impact on patients and programmes; implications for policies. Trop Med Int Health 2005;10:734–42. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01456.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zenebe Y, Adem Y, Mekonnen D, et al. . Profile of tuberculosis and its response to anti-TB drugs among tuberculosis patients treated under the TB control programme at Felege-Hiwot referral Hospital, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2016;16:688 10.1186/s12889-016-3362-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wondale B, Medihn G, Teklu T, et al. . A retrospective study on tuberculosis treatment outcomes at Jinka General Hospital, southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2017;10:680 10.1186/s13104-017-3020-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Asres A, Jerene D, Deressa W. Tuberculosis treatment outcomes of six and eight month treatment regimens in districts of southwestern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:653 10.1186/s12879-016-1917-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Dara M, Acosta CD, Melchers NVSV, et al. . Tuberculosis control in prisons: current situation and research gaps. Int J Infect Dis 2015;32:111–7. 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Seid MA, Ayalew MB, Muche EA, et al. . Drug-Susceptible tuberculosis treatment success and associated factors in Ethiopia from 2005 to 2017: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022111 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. World Health Organization The end TB strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 75. World Health Organization Everybody business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes : WHO’s framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland, 2007: 3, 14. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ahmed M, Fatmi Z, Ali S, et al. . Knowledge, attitude and practice of private practitioners regarding TB-DOTS in a rural district of Sindh, Pakistan. Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2009;21:28–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. United States Government Global tuberculosis strategy 2015-2019. 21 Washington, D.C, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Hoa NP, Diwan VK, Co NV, et al. . Knowledge about tuberculosis and its treatment among new pulmonary TB patients in the North and central regions of Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:603–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Adamu AL, Aliyu MH, Galadanci NA, et al. . The impact of rural residence and HIV infection on poor tuberculosis treatment outcomes in a large urban Hospital: a retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:4 10.1186/s12939-017-0714-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Fatiregun AA, Ojo AS, Bamgboye AE. Treatment outcomes among pulmonary tuberculosis patients at treatment centers in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann Afr Med 2009;8:100 10.4103/1596-3519.56237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gabida M, Tshimanga M, Chemhuru M, et al. . Trends for tuberculosis treatment outcomes, new sputum smear positive patients in Kwekwe district, Zimbabwe, 2007-2011: a cohort analysis. J Tuberc Res 2015;03:126–35. 10.4236/jtr.2015.34019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jones-López EC, Ayakaka I, Levin J, et al. . Effectiveness of the standard WHO recommended retreatment regimen (category II) for tuberculosis in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000427 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kirenga BJ, Levin J, Ayakaka I, et al. . Treatment outcomes of new tuberculosis patients hospitalized in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:e90614 10.1371/journal.pone.0090614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Musaazi J, Kiragga AN, Castelnuovo B, et al. . Tuberculosis treatment success among rural and urban Ugandans living with HIV: a retrospective study. Public Health Action 2017;7:100–9. 10.5588/pha.16.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nabukenya-Mudiope MG, Kawuma HJ, Brouwer M, et al. . Tuberculosis retreatment 'others' in comparison with classical retreatment cases; a retrospective cohort review. BMC Public Health 2015;15:840 10.1186/s12889-015-2195-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ofoegbu OS, Odume BB. Treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients at national Hospital Abuja Nigeria: a five year retrospective study. South African Family Practice 2015;57:50–6. 10.1080/20786190.2014.995913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tafess K, Beyen TK, Abera A, et al. . Treatment outcomes of tuberculosis at Asella teaching Hospital, Ethiopia: ten years' retrospective aggregated data. Front Med 2018;5 10.3389/fmed.2018.00038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Srinath S, et al. . Treatment outcomes of adult patients with recurrent tuberculosis in relation to HIV status in Zimbabwe: a retrospective record review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:124 10.1186/1471-2458-12-124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tweya H, Feldacker C, Phiri S, et al. . Comparison of treatment outcomes of new smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients by HIV and antiretroviral status in a TB/HIV clinic, Malawi. PLoS One 2013;8:e56248 10.1371/journal.pone.0056248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ukwaja KN, Oshi SN, Alobu I, et al. . Six- vs. eight-month anti-tuberculosis regimen for pulmonary tuberculosis under programme conditions. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19:295–301. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. van den Boogaard J, Lyimo R, Irongo CF, et al. . Community vs. facility-based directly observed treatment for tuberculosis in Tanzania's Kilimanjaro region. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2009;13:1524–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zenebe T, Tefera E. Tuberculosis treatment outcome and associated factors among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in afar, eastern Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Braz J Infect Dis 2016;20:635–6. 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029400supp001.pdf (34.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp002.pdf (45.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp003.pdf (47.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp005.pdf (55.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp006.pdf (162.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-029400supp004.pdf (43.7KB, pdf)