Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the prevalence and influencing factors of physical activity (PA) and sedentary behaviour (SB) in rural areas of China.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

A multistage, stratified cluster sampling method was used to obtain samples in the general population of Henan province in China.

Participants

38 515 participants aged 18–79 years were enrolled from the Henan Rural Cohort Study for the cross-sectional study.

Main outcome measures

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire was used to assess the levels of PA and SB. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to calculate ORs and 95% CIs of potential influencing factors with physical inactivity.

Results

The age-standardised prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day were 32.74% and 26.88% in the general Chinese rural adults, respectively. Gender differences were: 34.91%, 29.76% for men and 31.75%, 25.16% for women, respectively. The prevalence of participants with both light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day was 13.95%. Education at least junior middle school, divorced/widowed/unmarried, RMB1000> per capita monthly income ≥RMB500, sitting >7.5 hours per day were negatively associated with light PA. For sitting >7.5 hours per day, the negative factors were being men, divorced/widowed/unmarried, heavy smoking, Fishery products, vegetable and fruits intake.

Conclusion

Physical inactivity and SB were high in rural China. There is an increased need to promote a healthy lifestyle to the rural population.

Clinical trial registration

The Henan Rural Cohort Study has been registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Register.

Registration number: ChiCTR-OOC-15006699. http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=11375

Keywords: physical activity, sedentary behavior, prevalence, rural population

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study was focused on the rural population.

The study was based on a large sample.

Enough potential confounding variables were included in this study.

The study was based on a cross-sectional study.

The questionnaire was a standard version.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, epidemiological studies have suggested that physical inactivity or sedentary behaviour (SB) were risk factors for non-communicable diseases, such as breast cancer,1 prostate cancer,2 cardiovascular diseases,3 stroke,4 type 2 diabetes mellitus5 and metabolic syndrome.6 Moreover, a study ranging from the eastern Mediterranean to the western Pacific region showed that more than 5.3 million deaths could be avoided each year, if inactive people became active.7 In addition to the burden of disease, physical inactivity and SB also result in substantial economic burden to patients and society, especially in rural areas with limited resources.8

The prevalence of physical inactivity was about 31.1% all over the world, and varied by region. For instance, the prevalence of physical inactivity was 43.3% in USA, while it was just 17.0% in south-east Asia.9 Even within a country, the prevalence of physical inactivity varies from region to region. In China, the prevalence of physical inactivity was 63.1% in Shenzhen,10 and another study in Shanghai showed that only 18.4% of participants showed physical activity (PA).11 Although previous studies had explored the prevalence of PA and SB among inhabitants of urban China, there is little evidence of these in rural areas of China that have undergone rapid socioeconomic development.12 Therefore, it is necessary to update the prevalence and risk factors of PA and SB and then evaluate the levels of PA and SB in rural areas of China, to gather important evidence to generate strategy and promote PA in the population.

The objectives of the current study were: (1) To explore the prevalence of PA and SB. (2) To investigate potential influencing factors of PA and SB.

Methods

Settings and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from 2015 to 2017 in five rural regions (Suiping, Yuzhou, Xinxiang, Tongxu and Yima counties) of Henan province. The participants were permanent residents aged 18–79 years. Seven hundred and forty-four participants with insufficient information about their PA and sitting time were excluded. Ultimately, 38 515 participants with completed questionnaires, anthropometric measurements and blood tests were included in our analysis.

Data collection

The details of the sampling process were previously reported.13 Briefly, a multistage, stratified cluster sampling method was used. In the first stage, five rural counties were selected in central, south, north, east and west Henan province. In the second stage, one to three rural communities (referred to as ‘townships’) in each county were selected. In the last stage, all permanent residents who were 18–79 years old and who signed informed consent were selected as the study sample. The information was collected by face-to-face interview. The data about general demographic characteristics and lifestyles were included in a standard questionnaire. Educational level was classified into primary school or below and junior middle school or above, and marital status into married/cohabitation and unmarried/divorced/widowed categories. In accordance with the smoking index of WHO,14 the smoking status was divided into never smoking, light smoking, moderate smoking and heavy smoking. According to daily alcohol intake of WHO,14 drinking was categorised into never drinking, light drinking, moderate drinking and heavy drinking. According to Chinese dietary guidelines,15 four aspects were considered while evaluating dietary habits: meat and poultry, fishery products, vegetables and fruits, and soy products. The waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm at 1 cm above the navel in a horizontal plane, by a non-elastic tape. Height was measured twice to the nearest 0.1 cm, without shoes, using a wall-mounted ruler tape with an insertion buckle at one end. Body weight, using a mechanical scale on a level surface to the nearest 0.1 kg, was measured once with the subjects in light clothing and barefoot.16 Body mass index was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in developing this project.

Definitions

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to assess the levels of PA and SB.17 All the weekly time of vigorous activity, moderate activity and walking was calculated with the number of Mets (multiples of the basal metabolic rate) in each category and the daily average estimated. Mets reflected the energy expenditure specific for vigorous activity, moderate activity and walking. In this study, 1 MET was defined as the energy spent when an individual sits quietly. The Mets of vigorous activity was 8; the Mets of moderate activity was 4; the Mets of walking was 3.3. The value of Mets was estimated by the sum of the three PAs in 1 week. The PAs categorised into three levels were light (physically inactive), moderate and vigorous.9 18 These categories were based on the standard scoring criteria of IPAQ. Vigorous activity should meet either of the following two criteria: (1) Vigorous activity was at least 3 days/week and the week of accumulating Mets was at least 1500 MET-min/week. (2) Any combination of vigorous activity, moderate activity or walking at least 5 days/week and the accumulating Mets was at least 3000 MET-min/week. Moderate activity should meet either of the following four criteria: (1) Moderate activity was at least 30 min in 5 days a week. (2) Vigorous activity was at least 20 min in 3 days a week. (3) Walking at least 30 min a day for five or more days a week. (4) The accumulating Mets, of any combination of moderate activity, vigorous activity or walking, was at least 600 MET-min/week in five or more days a week. The light activity category was for individuals who met neither vigorous activity nor moderate activity criteria. In addition, the cut-off point for SB was set at 7.5 hours.19 20 At the same time, according WHO, PA was classified into insufficiently active, active and highly active. Some moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity PA but less than 150 min of moderate-intensity PA a week or 75 min of vigorous-intensity PA or the equivalent combination was considered insufficiently active. The equivalent of 150–300 min of moderate-intensity PA a week was considered active. The equivalent of more than 300 min of moderate-intensity PA a week was considered highly active.21 22

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean±SD. Differences between two groups were tested using t-test and more than two groups were tested using analysis of variance. Categorical variables, presented as numbers and percentages, were compared using the χ2 test. Based on the Chinese population data from the 2010 census, direct standardisation was used to calculate the age-standardised prevalence of Mets. Multinomial logistic regression models were used to calculate ORs and 95% CIs between the potential factors and Mets. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using SAS V.9.1 (SAS Institute, USA) and R V.3.5.1.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the 38 515 participants aged 18–79 years old. The mean (SD) age was 55.65 (12.14) years. Overall, a total of 11 510, 14 672 and 12 333 subjects were engaged in vigorous, moderate and light PA, respectively. Being male, married/cohabiting, light, moderate and heavy levels of smoking, and light and moderate drinking were more common among vigorous activity participants, while older age, widowed/single/divorced/separated, at least primary school education, per capita monthly income <RMB500, heavy drinking were more prevalent among moderate PA participants. Among the 38 515 participants, 28 270 were sitting ≤7.5 hours per day. Being female, married/cohabiting, at least junior school education, RMB500≤ per capita monthly income <RMB1000, never smoking and never drinking were more prevalent in the subjects sitting ≤7.5 hours per day than those sitting >7.5 hours per day (p<0.001). Online supplementary table 1 shows the demographic characteristics according to WHO.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants

| Variable | Overall (n=38 515) | Physical activity | P values | Sitting time per day | P values | |||

| Vigorous (n=11 510) |

Moderate (n=14 672) | Light (n=12 333) |

≤7.5 hours (n=28 270) | >7.5 hours (n=10 245) | ||||

| Age (years), mean±SD | 55.65±12.14 | 55.48±10.81 | 54.62±12.05 | 57.02±13.25 | <0.001 | 55.46±11.93 | 56.17±12.68 | <0.001 |

| Gender*, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Women | 60.52 (60.03 to 61.01) | 51.81 (50.89 to 52.72) | 70.90 (70.16 to 71.63) | 56.31 (55.44 to 57.19) | 62.21 (61.65 to 62.78) | 55.85 (54.89 to 56.81) | ||

| Men | 39.48 (38.99 to 39.97) | 48.19 (47.28 to 49.11) | 29.10 (28.37 to 29.84) | 43.69 (42.81 to 44.56) | 37.79 (37.22 to 38.35) | 44.15 (43.19 to 45.11) | ||

| Marital status*, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 89.76 (89.46 to 90.06) | 91.81 (91.31 to 92.31) | 90.18 (89.7 to 90.66) | 87.35 (86.76 to 87.94) | 90.21 (89.86 to 90.56) | 88.52 (87.9 to 89.14) | ||

| Widowed/single/divorced/separated | 10.24 (9.94 to 10.54) | 8.19 (7.69 to 8.69) | 9.82 (9.34 to 10.30) | 12.65 (12.06 to 13.24) | 9.79 (9.44 to 10.14) | 11.48 (10.86 to 12.10) | ||

| Education*, % (95% CI) | 0.234 | 0.001 | ||||||

| ≤ Primary school | 44.86 (44.36 to 45.35) | 44.74 (43.83 to 45.64) | 44.45 (43.64 to 45.25) | 45.46 (44.58 to 46.34) | 44.33 (43.75 to 44.91) | 46.31 (45.34 to 47.27) | ||

| ≥ Junior school | 55.14 (54.65 to 55.64) | 55.26 (54.36 to 56.17) | 55.55 (54.75 to 56.36) | 54.54 (53.66 to 55.42) | 55.67 (55.09 to 56.25) | 53.69 (52.73 to 54.66) | ||

| Per capita monthly income*, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| <RMB500 | 35.69 (35.21 to 36.17) | 36.22 (35.34 to 37.10) | 32.99 (32.23 to 33.76) | 38.40 (37.54 to 39.26) | 34.71 (34.15 to 35.26) | 38.40 (37.46 to 39.34) | ||

| RMB500~ | 32.86 (32.39 to 33.33) | 32.35 (31.50 to 33.21) | 33.80 (33.03 to 34.56) | 32.22 (31.40 to 33.05) | 34.38 (33.83 to 34.94) | 28.67 (27.79 to 29.54) | ||

| ≥RMB1000 | 31.45 (30.98 to 31.91) | 31.42 (30.58 to 32.27) | 33.21 (32.44 to 33.97) | 29.38 (28.57 to 30.18) | 30.91 (30.37 to 31.45) | 32.93 (32.02 to 33.84) | ||

| Smoking*, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 72.76 (72.31 to 73.20) | 66.48 (65.62 to 67.34) | 80.21 (79.56 to 80.85) | 69.76 (68.95 to 70.57) | 74.03 (73.52 to 74.54) | 69.24 (68.35 to 70.14) | ||

| Light | 5.59 (5.36 to 5.82) | 6.83 (6.37 to 7.29) | 4.26 (3.93 to 4.59) | 6.01 (5.59 to 6.43) | 5.66 (5.39 to 5.93) | 5.40 (4.96 to 5.84) | ||

| Moderate | 4.54 (4.34 to 4.75) | 5.49 (5.07 to 5.91) | 3.44 (3.15 to 3.74) | 4.97 (4.59 to 5.35) | 4.43 (4.19 to 4.67) | 4.86 (4.44 to 5.28) | ||

| Heavy | 17.11 (16.73 to 17.49) | 21.20 (20.45 to 21.95) | 12.09 (11.56 to 12.62) | 19.27 (18.57 to 19.96) | 15.88 (15.46 to 16.31) | 20.50 (19.72 to 21.28) | ||

| Drinking*, % (95% CI) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Never | 77.46 (77.04 to 77.88) | 71.74 (70.92 to 72.56) | 83.31 (82.70 to 83.91) | 75.84 (75.08 to 76.59) | 78.06 (77.58 to 78.54) | 75.79 (74.96 to 76.62) | ||

| Light | 13.92 (13.57 to 14.26) | 17.94 (17.24 to 18.64) | 10.39 (9.90 to 10.89) | 14.35 (13.73 to 14.97) | 13.58 (13.18 to 13.98) | 14.84 (14.15 to 15.52) | ||

| Moderate | 4.73 (4.51 to 4.94) | 5.80 (5.38 to 6.23) | 3.64 (3.34 to 3.94) | 5.01 (4.63 to 5.40) | 4.78 (4.53 to 5.03) | 4.58 (4.17 to 4.98) | ||

| Heavy | 3.90 (3.71 to 4.09) | 4.52 (4.14 to 4.90) | 2.66 (2.40 to 2.92) | 4.80 (4.42 to 5.18) | 3.58 (3.36 to 3.79) | 4.79 (4.38 to 5.21) | ||

| Dietary habits (kg/month), (mean±SD) | ||||||||

| Meat and poultry | 1.32±1.32 | 1.21±1.28 | 1.40±1.35 | 1.33±1.33 | <0.001 | 1.31±1.33 | 1.34±1.31 | 0.410 |

| Fishery products | 0.11±0.16 | 0.10±0.15 | 0.12±0.16 | 0.11±0.16 | <0.001 | 0.11±0.16 | 0.13±0.17 | <0.001 |

| Vegetables and fruits | 13.8±7.47 | 12.49±7.43 | 14.68±7.37 | 14.07±7.44 | <0.001 | 13.27±7.23 | 15.24±7.91 | <0.001 |

| Soy products | 0.48±0.64 | 0.41±0.60 | 0.49±0.65 | 0.53±0.67 | <0.001 | 0.49±0.65 | 0.46±0.63 | <0.001 |

| Height (cm), mean±SD | 159.69±8.20 | 160.65±8.24 | 158.62±7.84 | 160.07±8.43 | <0.001 | 159.59±8.17 | 159.98±8.28 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 63.48±11.14 | 63.92±10.86 | 62.44±10.76 | 64.30±11.72 | <0.001 | 63.60±11.09 | 63.15±11.27 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 24.84±3.57 | 24.72±3.46 | 24.77±3.50 | 25.03±3.73 | <0.001 | 24.92±3.56 | 24.61±3.59 | <0.001 |

| WC (cm), mean±SD | 84.07±10.41 | 83.65±10.03 | 83.44±10.19 | 85.22±10.90 | <0.001 | 84.42±10.35 | 83.10±10.50 | <0.001 |

*Was presented as % and 95% CIs.

BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference.

bmjopen-2019-029590supp001.pdf (197.8KB, pdf)

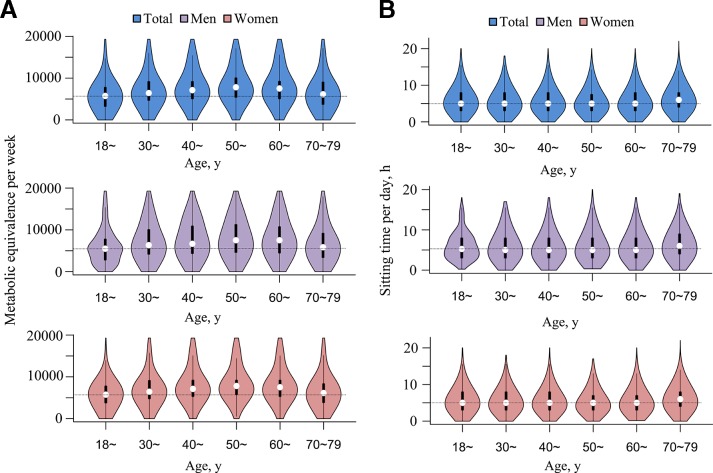

The gender-specific distributions of PA and sitting time according to age

Figure 1 describes the gender-specific distribution of the Mets of PA and sitting time according to age. The median of Mets for PA and sitting time were 7092 MET-min/week and 5 hours, respectively. The median of Mets for PA were 6558 MET-min/week and 7119 MET-min/week for men and women, respectively. The median of sitting time were 5 hours for both men and women. The mean±SD of Mets for PA was 7626.02±4229.32 MET-min/week and sitting time was 5.70±3.23 hours. The mean±SD of Mets for PA and sitting time were 7506.15±4524.75 MET-min/week, 7704.20±4023.12 MET-min/week and 5.97±3.39 hours, 5.53±3.12 hours for men and women (p<0.001), respectively. Notably, the sitting time of men was higher than that of women. The 50–59 years age group had the highest Mets. The 70–79 years age group had the highest sitting time.

Figure 1.

The violin chart of metabolic equivalence per week and sitting time per day according to gender and age. (A) Metabolic equivalence per week. (B) Sitting time per day. h, hours; y, years.

Prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day

Online supplementary table 2 displays the prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day among various characteristics. The prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day were 32.02% and 26.60%, and the age-standardised prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day were 32.74% and 26.88% in the general Chinese rural adults, respectively. Gender differences were: 34.91%, 29.76% for men and 31.75%, 25.16% for women, respectively. Subgroup study showed that the prevalence of low PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day were higher in those who were younger or older, male, widowed/single/divorced/separated with lower per capita monthly income, heavy smoking and drinking.

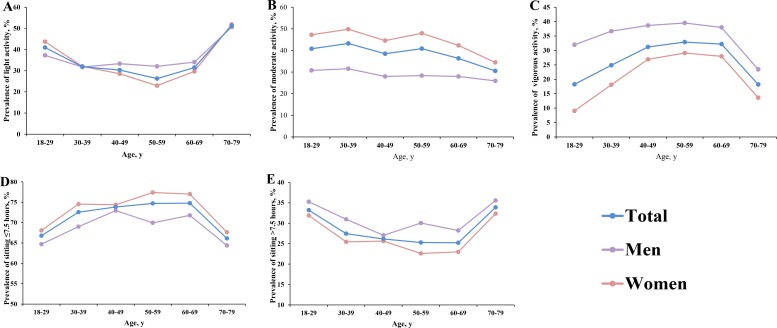

Changes of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day in different subgroups

Figure 2 shows that the age-standardised prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day changed with age in both sexes. The prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day decreased with age first and then increased. Men had higher probability of having high PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day than women in all the age groups. Online supplementary figure 1 shows the age-standardised prevalence according to WHO.

Figure 2.

Changes in the age-standardised prevalence of physical activity and sitting time with age in different genders. (A) Light physical activity. (B) Moderate physical activity. (C) Vigorous physical activity. (D) Sitting time ≤7.5 hours per day. (E) Sitting time >7.5 hours per day. y, years.

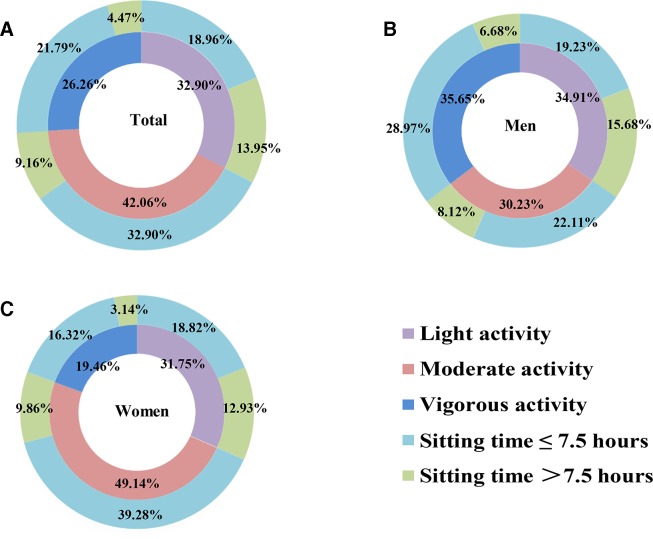

The percentage according to the cut-off points of PA and sitting time in different sexes

Figure 3 shows the age-standardised percentage according to the cut-off points of PA and sitting time in different sexes. Seventeen thousand three hundred and forty-six subjects (7434 men and 9912 women) had light PA or sitting >7.5 hours per day, and the corresponding age-standardised prevalence was 46.53% (49.71% in men and 44.75% in women). The age-standardised prevalence of participants with both light PA and single sitting >7.5 hours per day was 13.95% (15.68% in men and 12.93% in women). Online supplementary figure 2 shows the age-standardised percentage according to WHO cut-off points and sitting time.

Figure 3.

The age-standardised percentage according to the cut-off points of physical activity and sitting time in different genders. (A) Total. (B) Men. (C) Women.

Analysis of influencing determinants

Table 2 describes the ORs of the association of potential influencing determinants with light PA and sitting time >7.5 hours per day. Being female, in the 18–29 years age group, level of education at least junior middle school, divorced/widowed/unmarried, RMB1000 >per capita monthly income ≥RMB500, never smoking and drinking, and sitting time per day were significantly negatively associated with light PA; while being male, level of education upto primary school, per capita monthly income <RMB500, heavy smoking and drinking, fishery products, vegetables and fruits, were significantly negatively associated with sitting >7.5 hours per day. Online supplementary table 3 shows the potential influencing determinants according to WHO.

Table 2.

Association of potential risk factors for physical activity and sitting time

| Factors | OR (95% CI) | |||||

| Physical activity | Sitting time per day | |||||

| Moderate* | Moderate† | Light* | Light† | >7.5 hours* | >7.5 hours† | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 18- | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30- | 0.67 (0.56 to 0.81) | 0.70 (0.58 to 0.85) | 0.58 (0.48 to 0.70) | 0.63 (0.51 to 0.76) | 0.99 (0.85 to 1.14) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.22) |

| 40- | 0.49 (0.41 to 0.57) | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.62) | 0.42 (0.36 to 0.50) | 0.47 (0.39 to 0.56) | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.04) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.13) |

| 50- | 0.48 (0.41 to 0.57) | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.61) | 0.36 (0.30 to 0.42) | 0.39 (0.33 to 0.47) | 0.87 (0.76 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.82 to 1.09) |

| 60- | 0.45 (0.38 to 0.52) | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.61) | 0.46 (0.39 to 0.54) | 0.51 (0.43 to 0.62) | 0.89 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.89 (0.77 to 1.02) |

| 70–79 | 0.62 (0.52 to 0.74) | 0.72 (0.60 to 0.87) | 1.13 (0.95 to 1.35) | 1.17 (0.97 to 1.42) | 1.34 (1.17 to 1.54) | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.26) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Male | 0.44 (0.42 to 0.46) | 0.46 (0.43 to 0.50) | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.88) | 0.76 (0.70 to 0.83) | 1.30 (1.24 to 1.36) | 1.25 (1.16 to 1.35) |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤ Primary school | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≥ Junior middle school | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.14) | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.02) | 1.27 (1.20 to 1.35) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.85 (0.81 to 0.90) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/cohabiting | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Divorced/widowed/unmarried | 1.22 (1.12 to 1.33) | 1.15 (1.05 to 1.26) | 1.62 (1.49 to 1.77) | 1.19 (1.09 to 1.31) | 1.20 (1.11 to 1.28) | 1.08 (1.00 to 1.17) |

| Per capita monthly income | ||||||

| <RMB500 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| RMB500- | 1.15 (1.08 to 1.22) | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 1.08 (1.01 to 1.15) | 0.75 (0.71 to 0.80) | 0.79 (0.75 to 0.84) |

| ≥RMB1000 | 1.16 (1.09 to 1.23) | 1.13 (1.06 to 1.21) | 0.88 (0.83 to 0.94) | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 0.96 (0.91 to 1.02) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.07) |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Light | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.58) | 0.57 (0.51 to 0.64) | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.93) | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89) | 1.04 (0.93 to 1.16) | 0.88 (0.78 to 0.99) |

| Moderate | 0.52 (0.46 to 0.59) | 0.61 (0.54 to 0.69) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.97) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) | 1.21 (1.07 to 1.36) | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) |

| Heavy | 0.47 (0.44 to 0.51) | 0.57 (0.52 to 0.61) | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.92) | 0.83 (0.77 to 0.90) | 1.41 (1.33 to 1.51) | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.31) |

| Drinking, | ||||||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Light | 0.50 (0.46 to 0.54) | 0.64 (0.59 to 0.69) | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.81) | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.87) | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.28) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) |

| Moderate | 0.54 (0.48 to 0.61) | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.81) | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.91) | 0.93 (0.82 to 1.05) | 1.08 (0.96 to 1.22) | 0.82 (0.72 to 0.92) |

| Heavy | 0.51 (0.44 to 0.58) | 0.70 (0.61 to 0.81) | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.13) | 1.10 (0.96 to 1.27) | 1.31 (1.16 to 1.48) | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.21) |

| Dietary habits | ||||||

| Meat and poultry | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | 1.08 (1.06 to 1.10) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.97) |

| Fishery products | 1.16 (0.99 to 1.34) | 0.97 (0.82 to 1.16) | 0.61 (0.52 to 0.72) | 0.76 (0.63 to 0.93) | 2.16 (1.86 to 2.52) | 2.21 (1.87 to 2.60) |

| Vegetables and fruits | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.01) | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | 0.96 (0.96 to 0.97) | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.04) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.05) |

| Soy products | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.94) | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.92) | 0.74 (0.71 to 0.77) | 0.81 (0.78 to 0.85) | 0.91 (0.87 to 0.95) | 0.91 (0.88 to 0.95) |

| Sitting time per day | ||||||

| ≤7.5 hours | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | – | – |

| >7.5 hours | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.42) | 1.35 (1.27 to 1.44) | 3.68 (3.47 to 3.91) | 4.09 (3.84 to 4.36) | – | – |

| Physical activity | ||||||

| Vigorous | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Moderate | – | – | – | – | 1.34 (1.25 to 1.42) | 1.37 (1.28 to 1.46) |

| Light | – | – | – | – | 3.68 (3.47 to 3.91) | 4.08 (3.83 to 4.34) |

*Was a crude model;.

†Was a full model: adjusted for age, gender, education, marital status, per capita monthly income, smoking, drinking and dietary habits.

Discussion

Results of this large survey provided new insights on PA and SB among the rural population in the Henan province of China. Overall, the median levels of sitting time were higher in adults in rural China compared with a previous study of a 20-country comparison of sitting,23 and the percentage levels of physical inactivity were higher in Chinese rural adults than in the previous study of global PA levels.9 At first PA decreased with age; then there was an increase in the prevalence of light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day. The percentage of men, women and total individuals that had both light PA and sitting >7.5 hours per day were 15.68%, 12.93% and 13.95%, respectively. Further multiple logistic regression analysis found gender, age, level of education, marital status, smoking, drinking and vegetables intake were influencing factors for light PA and sitting >7.5 hours.

Previous studies had shown that the levels of physical inactivity and SB were high in urban China.10 11 Compared with urban areas, rural areas are at a relatively low level. The difference might be explained by the level of development. The mean of Mets increased with age initially and then decreased in the 50–59 years age group, while the sitting time was highest in the 70–79 years age group. It is likely that the decline in physical ability with age limits PA and increases the sedentary nature of the elderly.24 Furthermore, the aged might fear injuries, which was another reason leading to their physical inactivity.25 Subgroup analysis of PA showed that under the various categories, the prevalence of vigorous PA was about 30%, moderate PA was about 40% and light PA was about 30%, whereas sitting time, under the various categories, ≤7.5 hours per day was about 70%. These results were similar to that from a Chilean study.23

The results of coexistence of PA and SB showed that light PA and sitting time >7.5 hours per day were 15.68%, 12.93% and 13.95 in men, women and totally, respectively. These results were similar to that from a study from Japan.26 Participants with light PA and sitting time >7.5 hours per day, should adopt measures to promote their PA.

Evidence showed that there were negative relationships between junior middle school education level or above, divorced/widowed/unmarried, per capita monthly income ≥RMB500, and meat and poultry consumption, and moderate PA. Having a junior middle school education level or above, divorced/widowed/unmarried, RMB1000> per capita monthly income ≥RMB500, and sitting time per day >7.5 hours were negatively associated with light PA. For sitting >7.5 hours per day, the negative factors were being male, divorced/widowed/unmarried, heavy smoking, fishery products and vegetable and fruits intake.

The current study focused on the epidemiological characteristics of PA and SB based on a relatively large sample size of the rural population in the Henan province of China. Although a series of measures, such as standardised tools and training implementation, had been adopted to guarantee the authenticity, there were several limitations. First, these results were based on a cross-sectional study, so the causal relationships between factors and PA or SB could not be confirmed. Second, the responses were from self-reported data, which could distort real facts. Third, according to the actual rural circumstances, the residents who studied or worked in cities were not included in this study, so the prevalence of Mets in the rural population might be overestimated or underestimated. Fourth, the subjects included in the present study had an asymmetrical age structure, which might lead to potential bias of IPAQ. Fifth, according to the actual rural circumstances, the residents who studied or worked in the city were not included in this study, so the prevalence of PA and SB in the rural population could be overestimated. Although these limitations exist, the relatively large sample size of this epidemiological study could reflect the prevalence of PA and SB in rural areas of China.

Conclusion

This study suggests a relatively higher prevalence of physical inactivity and SB among Chinese rural adults as a result of economic and social transition. More attention should be given to the aged population and to individuals who drink who are at high risk of physical inactivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants, coordinators and administrators for their support and help during the research. The authors also thank Dr Tanko Abdulai for his critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

RT and YL contributed equally.

Contributors: CW and YW conceived and designed the study. RT, YL, LS, HY, ZM, XL, HZ, LZ and RL coordinated data collection. YL, LS, HJ, ZM, XL, HZ, LZ and RL conducted the analyses. RT wrote the manuscript. All coauthors critically revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program Precision Medicine Initiative of China (Grant No: 2016YFC0900803), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 81573243, 81602925), Henan Science and Technology Development Funds (Grant No: 182207310001), Henan Natural Science Foundation (Grant No: 182300410293), Science and Technology Foundation for Innovation Talent of Henan Province (Grant No: 164100510021), Science and Technology Innovation Talents Support Plan of Henan Province Colleges and Universities (Grant No: 14HASTIT035). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: All permanent residents who signed informed consent were selected as the study sample.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethics approval was obtained from the 'Zhengzhou University Life Science Ethics Committee', and written informed consent was obtained for all participants. Ethics approval code: (2015) MEC (S128). The purpose and the importance of the study were explained to the participants. Confidentiality of the information was maintained throughout the study by excluding personal identifiers from the data collection form.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All relevant data are included in the paper and the online supplementary file. Additional information regarding data access can be obtained from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Fararouei M, Iqbal A, Rezaian S, et al. . Dietary habits and physical activity are associated with the risk of breast cancer among young Iranian women: a case-control study on 1010 premenopausal women. Clin Breast Cancer 2019;19:S1526-8209(18)30622-0 10.1016/j.clbc.2018.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sormunen J, Talibov M, Sparén P, et al. . Perceived physical strain at work and incidence of prostate cancer – a case-control study in Sweden and Finland. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2018;19:2331–5. 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.8.2331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ambakederemo TE, Chikezie EU. Assessment of some traditional cardiovascular risk factors in medical doctors in southern Nigeria. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2018;14:299–309. 10.2147/VHRM.S176361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sarfo FS, Mobula LM, Plange-Rhule J, et al. . Incident stroke among Ghanaians with hypertension and diabetes: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. J Neurol Sci 2018;395:17–24. 10.1016/j.jns.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chang C, Khurana S, Strodel R, et al. . Perceived barriers to physical activity among low-income Latina women at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2018;44:444–53. 10.1177/0145721718787782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. El Bilbeisi AH, Hosseini S, Djafarian K. The association between physical activity and the metabolic syndrome among type 2 diabetes patients in Gaza strip, Palestine. Ethiop J Health Sci 2017;27:273–82. 10.4314/ejhs.v27i3.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. . Lancet physical activity series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012;380:219–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ding D, Lawson KD, Kolbe-Alexander TL, et al. . Lancet physical activity series 2 executive Committee. The economic burden of physical inactivity: a global analysis of major non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2016;388:1311–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, et al. . Lancet physical activity series Working Group. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet 2012;380:247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou Y, Wu J, Zhang S, et al. . Prevalence and risk factors of physical inactivity among middle-aged and older Chinese in Shenzhen: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019775 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen S-T, Liu Y, Hong J-T, et al. . Co-Existence of physical activity and sedentary behavior among children and adolescents in Shanghai, China: do gender and age matter? BMC Public Health 2018;18:1287 10.1186/s12889-018-6167-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ding C, Song C, Yuan F, et al. . The physical activity patterns among rural Chinese adults: data from China national nutrition and health survey in 2010–2012. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15:941 10.3390/ijerph15050941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu X, Mao Z, Li Y, et al. . The Henan rural cohort: a prospective study of chronic non-communicable diseases. Int J Epidemiol 2019;387 10.1093/ije/dyz039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ediriweera BR TS, Sir RD, Robin R. International guide for monitoring alcohol consumption and related harm. 51 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chinese Nutrition Society The dietary guidelines for Chinese residents. Lhasa: The Tibet people's Publishing House, 2011: 97–198. [Google Scholar]

- 16. People’s Republic of China Ministry of Health Disease Control Division Overweight and Obesity Prevention and Control Guidelines in Chinese Adults, People’s Republic of China Ministry of Health Disease Control Division, Beijing, China; 2003.

- 17. Bennie JA, Chau JY, van der Ploeg HP, et al. . The prevalence and correlates of sitting in European adults - a comparison of 32 Eurobarometer-participating countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10 10.1186/1479-5868-10-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bauman A, Bull F, Chey T, et al. . The International prevalence study on physical activity: results from 20 countries. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2009;6 10.1186/1479-5868-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lakerveld J, Loyen A, Schotman N, et al. . Sitting too much: a hierarchy of socio-demographic correlates. Prev Med 2017;101:77–83. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Milton K, Gale J, Stamatakis E, et al. . Trends in prolonged sitting time among European adults: 27 country analysis. Prev Med 2015;77:11–16. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bauman A, Ainsworth BE, Sallis JF, et al. . The descriptive epidemiology of sitting. A 20-country comparison using the International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ). Am J Prev Med 2011;41:228–35. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, et al. . Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the third National health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-1994. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:46–53. 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00105-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Celis-Morales C, Salas C, Alduhishy A, et al. . Socio-Demographic patterns of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in Chile: results from the National health survey 2009–2010. J Public Health 2016;38:e98–105. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liao Y, Shibata A, Ishii K, et al. . Independent and combined associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with depressive symptoms among Japanese adults. Int J Behav Med 2016;23:402–9. 10.1007/s12529-015-9484-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-029590supp001.pdf (197.8KB, pdf)