Abstract

Introduction

Children and young people (CYP) in the UK have poor health outcomes, and there is increasing emergency department and hospital outpatient use. To address these problems in Lambeth and Southwark (two boroughs of London, UK), the local Clinical Commissioning Groups, Local Authorities and Healthcare Providers formed The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership (CYPHP), a clinical-academic programme for improving child health. The Partnership has developed the CYPHP Evelina London model, an integrated healthcare model that aims to deliver effective, coordinated care in primary and community settings and promote better self-management to over approximately 90 000 CYP in Lambeth and Southwark. This protocol is for the process evaluation of this model of care.

Methods and analysis

Alongside an impact evaluation, an in-depth, mixed-methods process evaluation will be used to understand the barriers and facilitators to implementing the model of care. The data collected mapped onto a logic model of how CYPHP is expected to improve child health outcomes. Data collection and analysis include qualitative interviews and focus groups with stakeholders, a policy review and a quantitative analysis of routine clinical and administrative data and questionnaire data. Information relating to the context of the trial that may affect implementation and/or outcomes of the CYPHP model of care will be documented.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been reviewed by NHS REC Cornwall & Plymouth (17/SW/0275). The findings of this process evaluation will guide the scaling up and implementation of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care across the UK. Findings will be disseminated through publications and conferences, and implementation manuals and guidance for others working to improve child health through strengthening health systems.

Trial registration number

Keywords: child health, process evaluation, integrated care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This process evaluation will provide insights into how integrated care programmes can be implemented for children and young people at scale.

The evaluation using robust mixed quantitative and qualitative methods is grounded within a theoretically informed logic model and uses the RE-AIM Framework.

Stakeholders may be reluctant to discuss unwillingness to deliver intervention components or negative perspectives of the model of care.

Triangulation of data sources will maximise credibility and validity.

Introduction

The state of children’s health is a growing concern across the UK, and health services and systems contribute to suboptimal outcomes.1 2 In the context of increases in the numbers of children and young people (CYP) living with long-term conditions (physical and psychosocial) and multimorbidity, current fractures within the system and healthcare delivery allow individuals to ‘fall through the gaps’ in care.3 4

In the UK, paediatric healthcare models were originally developed to deliver acute, inpatient and high intensity specialist services rather than to prevent illness and disease complications and maximise well-being and developmental potential.5 Despite improvements, current services are not as responsive to families' needs as they should be and are often inefficient with a reliance on high cost emergency department attendance and acute admissions.5–7 To improve CYP’s health, more effective, evidence-based care models are needed, together with public health, social and economic policies to promote and protect health. Integrated care models may represent a solution to problems facing child health services.5 The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership (CYPHP) Evelina London Model of Care is a new and integrated model of care for CYP that is part of a health systems strengthening programme.

This paper describes the protocol for a mixed methods process evaluation, embedded within a clustered randomised controlled trial (cRCT), to assess the impact of a complex intervention to integrate and improve healthcare for CYP (the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care). CYPHP will deliver services to over approximately 90 000 CYP in Lambeth and Southwark, two of the most deprived boroughs in the UK. There is a lack of comprehensive rigorous evidence about integrated models of care for CYP; the evaluation of the CYPHP Evelina London model of care will help fill this evidence gap by providing information on effectiveness and the process of implementing integrated models of care. This process evaluation aims to complement the cRCT of outcomes,8 to understand how and why the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care achieved its outcomes and to inform stakeholders about how the CYPHP Evelina Model of Care could be implemented in other settings.

The intervention: The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership (CYPHP) Evelina London Model of Care

The CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care is a complex model comprising several interventions for CYP (0–16 years) and service providers. The aim of all interventions within the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care is to improve CYP health, healthcare quality, and strengthen the health system.

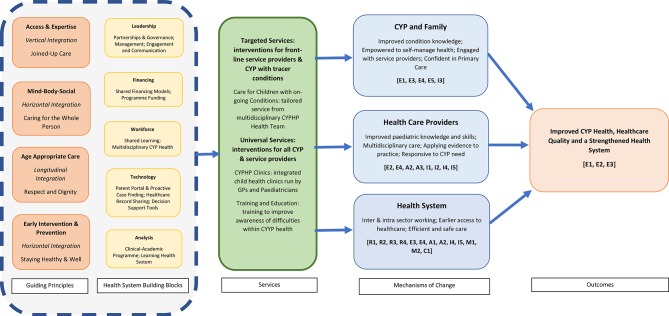

To facilitate the design and operationalisation of the programme, the measurement and analysis of the implementation and outcomes of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care, the components of the programme have been conceptualised as a theoretical framework (or logic model; see figure 1). The theoretical framework has been guided by the WHO health systems building blocks concept9 and was developed using workshop methods with the CYPHP programme team and wider stakeholders. The framework in figure 1 shows how the CYPHP guiding principles (eg, early intervention and prevention) and health system building blocks (eg, technology) are reflected in outputs (eg, interventions and targeted/universal services), that are in turn reflected in outcomes (eg, improved child health).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework for the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care; [x] represents process indicators which are detailed in table 1. The CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care provides numerous universal and targeted services; the interventions described here are provided as an example and are not exhaustive. CYP, children and young people; CYPHP, The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership.

The interventions within this framework were guided by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF),10 which describes 12 behavioural domains which interventions may target to influence behaviour change. In brief, the targeted and universal interventions within the CYPHP Model have been designed to target barriers to effective management of physical, mental, and social determinants of health at both the service-provider and patient-level to maximise behaviour change. In our accompanying paper, the hypothesised active components of each individual intervention have been mapped onto the TDF to evidence the proposed mechanisms of action through which the intervention may become effective.8 In addition, the mechanism of action across the whole programme, at the service provider, family, and system level is detailed in figure 1.

Providing care that is responsive to CYP’s needs will be achieved through roll-out of several universal and targeted services, examples of which are described below:

- Universal Services: interventions for all eligible CYP and service providers in Lambeth and Southwark.

- Education and Training: training to improve awareness of difficulties within CYP’s health and provision of young person-friendly training to service providers and school staff. These interventions aim to increase provider knowledge and skills, to improve delivery of CYP healthcare.

- CYPHP Clinics: integrated child health clinics run by General Practitioners (GPs) and local ‘Patch Paediatricians’ in primary care settings. These clinics are typically for CYP who would otherwise have been referred to hospital for an outpatient appointment with a general paediatrician. This intervention provides shared learning opportunities to develop service provider competence, and encourages team working between primary and secondary care, to provide better quality care and earlier access to healthcare for CYP.

- Targeted Services: interventions for eligible CYP with prespecified tracer conditions (asthma, eczema, epilepsy, constipation). Tracer conditions were chosen as they are examples of long-term and common conditions, which will provide generalisable lessons about improving outcomes for CYP with ongoing conditions. The intention is to design a generalisable model of care for CYP with common and chronic conditions as part of a health system response to the epidemiological transition to chronic disease.

- Care for CYP with ongoing conditions: CYP with tracer conditions are eligible for a tailored clinical service delivered by the multidisciplinary CYPHP Health Team in primary and community settings. Care includes heath promotion, preventative and reactive care and all decisions are documented and shared with GPs through electronic health records. Through the CYPHP Clinical Team, we anticipate that CYP motivation and goals will be targeted, changing CYP’s perceived competence and knowledge, allowing self-management of health.

To aid implementation of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care, regular meetings with primary and secondary care providers, local Clinical Commissioning Groups, GP Federations and materials to aid implementation using established behaviour change techniques were used. The implementation of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care across Lambeth and Southwark will occur in stages. This phased roll-out allowed the application of an opportunistic cRCT design, where for the first stage (approximately 2 years) GP practices are randomised to be offered either the CYPHP model (ie, delivery of targeted and universal services to eligible CYP) or enhanced usual care (ie, delivery of universal services only to eligible CYP). Details of the evaluation design are presented in the accompanying protocol paper.8

In summary, the evaluation has four component parts: the outcome evaluation consists of a pseudoanonymised population-based evaluation for all CYP in participating GP practices to explore changes in health service use across control and intervention arms; an evaluation of CYP with selected tracer conditions to understand changes in health and healthcare across control and intervention arms; and an economic evaluation to assess the costs of delivery and cost effectiveness of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care across tracer conditions. Alongside the outcome evaluation, a nested process evaluation, detailed in this paper, aims to understand how and why the CYPHP Evelina London model is effective or ineffective in achieving health, healthcare and health service use outcomes and to identify contextually relevant strategies for successful implementation as well as practical difficulties in adoption, delivery and maintenance to inform wider implementation.

The process of implementing a new clinical service

The process evaluation will focus on measures of implementation success, including reach, fidelity, adoption and maintenance of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care. Implementation science specifically looks at ways to enhance and promote the uptake of research findings and evidence-based practices into routine healthcare; implementation evaluation is therefore a key component of a comprehensive process evaluation for a complex intervention evaluation.11 12 Variation in implementation of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care is inevitable, due to multiple intervention components, diverse contexts and participants. Practices’ differing characteristics influence their care arrangements for CYP and will affect the roles and expectations of clinical and administrative staff. Similarly, patients' previous experience and expectations of care affects care-seeking behaviour. These differences, in the context of evolving local healthcare environments, policies and priorities may affect the successful implementation of the new model of care.13

Process evaluations need to be designed, delivered and analysed within a theoretical framework to allow clearer articulation of research questions, validated instruments to assess outcomes and theory-driven explanations for success or failure of implementation efforts. This is essential to understand the mechanisms which underlie the programme’s effectiveness and to application in other populations and settings. Glasgow’s RE-AIM Framework14 proposes five domains that can influence the implementation of new services across a range of stakeholders. The framework’s five domains guide the assessment of:

Reach, which captures the percentage of people from a given population who participate in a programme and describes their characteristics.

Effectiveness, which refers to the positive and negative outcomes of the programme

Adoption, which is generally defined as the per cent of possible settings (eg, organisations) and staff that have agreed to participate in the programme.

Implementation, which is an indicator of the extent to which the programme was delivered as intended and its cost.

Maintenance, which, at the individual level, reflects maintenance of the primary outcomes (>6 months).

The RE-AIM Framework has been applied to understand intervention impact across a variety of healthcare settings and acknowledges the value of qualitative data to complement quantitative measures.15 The core aspects of the RE-AIM Framework will be incorporated into our process evaluation and used to understand the interpretation of qualitative findings.

Aim

The overall aim of the CYPHP process evaluation is to better understand how and why the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care was effective or ineffective; to identify contextually relevant strategies for successful implementation and to identify practical difficulties and facilitators in adoption, delivery and maintenance to inform wider implementation. The overarching questions guiding the evaluation for the CYPHP Evelina London model of care are:

What factors contribute to the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care?

What factors contribute to successful or challenging implementation across study sites?

Methods

Patient and public involvement

The CYPHP Evelina London Model was developed with key stakeholders including CYP, carers, front line practitioners and health service commissioners. Stakeholders were involved in the development of the theoretical framework for CYPHP, identification of research questions and refining the research methodology, including the development of questions for qualitative interviews and focus groups.

Setting/target groups for process evaluation

The intervention components of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care are situated in primary care settings and the community. These interventions target service providers (GP receptionists, practice nurses, primary care providers), CYP and families. Commissioners of healthcare services in Lambeth and Southwark are not directly targeted by the intervention components, but as influential participants, they are included in the process evaluation.

Data collection

The process evaluation will use a mixed methods approach to data collection and analysis. We will use the following methods of data collection: (1) surveys of all stakeholders; (2) analysis of routine clinical and administrative data; (3) interviews and/or focus groups with stakeholders and (4) a review of policy documents during the planning and delivery of the CYPHP Evelina Model of Care. Data collection will be guided by the RE-AIM framework. The process indicators as per the RE-AIM framework are mapped into the logic model and presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Specification of the process evaluation

| RE-AIM dimension | Definition | Question | Process indicators (mapped to logic model) |

| Reach | Per cent and representativeness of individuals receiving the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care, of total eligible service users |

|

|

| Effectiveness | Impact of CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care on trial outcomes (reported elsewhere) [E1, E2]; fidelity of delivery |

|

|

| Adoption | Proportion and representativeness of settings, commissioners and providers willing to adopt (or commission) the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care |

|

|

| Implementation | The extent to which the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care is delivered as planned |

|

|

| Maintenance | Sustainability of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care at individual, setting and geographical/administrative levels |

|

|

| Context | Healthcare context throughout the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care implementation period |

|

|

[x] represents process indicators which are mapped onto figure 1.

CYP, children and young people; CYPHP, The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership; HCP, healthcare provider; NoMAD, Normalisation Process Theory Scale.

Surveys of all stakeholders

All primary care service providers participating in the intervention arms of the CYPHP Evelina Model of Care will be invited to complete the Normalisation Process Theory tool (NoMAD).16 Normalisation Process Theory (NPT)17 focuses on the implementation of new practices and how these new practices become embedded and sustained in their social contexts. The NoMAD is the NPT’s accompanying tool. The NoMAD tool consists of 23 items that measure the process of implementation from the perspectives of professionals directly involved in implementing complex interventions. The NoMAD tool was selected as it is the first validated measure to assess implementation processes and can be used across multiple stakeholders and settings, providing insight into the adoption of new services at the service provider level. In addition, routinely collected service satisfaction data from CYP and family surveys will be audited to assess satisfaction with the CYPHP services. Surveys will be distributed across service provider and commissioner channels across Lambeth and Southwark (eg, GP events, mailing lists and locality meetings), after implementation of the full CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care. The quantitative data collected from the NoMAD tool and service satisfaction questionnaires will be analysed using descriptive statistics.

Routine clinical and administrative data

Routinely collected data will be used to assess the proportion of service users and service providers who participate in each part of the CYPHP Evelina Model of Care (outlined in figure 1). Outcomes of service users who receive any element of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care and description of any relevant adverse clinical events will be documented (as detailed in table 1).

GP practices in the intervention arm will be profiled for size, organisational characteristics, GP characteristics (eg, number and whole time equivalent of GP partners and salaried staff, years qualified, proportion who have additional paediatric qualifications or special interests in child health) and the number of patients registered with the practice. This will facilitate assessment of practice context and effects of contextual variation. The quantitative data collected from all practices will be analysed using descriptive statistics to provide information about the differential implementation rates of the intervention components of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care. This will be related to trial outcomes and will facilitate comparison of practices regarding implementation fidelity and reach.

Interviews and/or focus groups with all stakeholders

Qualitative data will be collected through interviews and focus groups with commissioners, service providers, CYP and families who have participated in any component of the intervention arm of the CYPHP Evelina Model of Care. CYP and families will be invited to take part in a focus group or interview after discharge from the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care. Children under 12 years will only participate alongside their carer. Families will be reimbursed for any travel expenses, but no other form of incentive will be offered.

Sampling will be purposive rather than statistical, to include CYP and families from diverse settings with a wide range of circumstances that may influence responsiveness and accessibility to healthcare. Families will be contacted via the researcher, who is blinded to time, intensity or outcome of treatment.

Topic guides aim to elucidate narrative data on: the experience of CYPHP interventions, healthcare use, self-management and perspectives on care. A range of appropriate art-based methods (eg, pipe cleaners, drawing, puppets) will be used to engage younger children in the discussions.18 A facilitator, who is experienced in working with CYP and families, will guide discussions, which will be audio-recorded.

Primary care service providers involved in the delivery of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care will be invited to take part in one-to-one interviews. Completion of NoMAD surveys and administrative data (previously described) will be used as an indicator of engagement and implementation strength to inform recruitment of service providers to these interviews. This will result in sufficient heterogeneity to provide examples of relatively poor and good adoption, delivery and maintenance and will allow us to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation and to generate hypotheses about factors that may be associated with differing outcomes. Topic guides explore common issues when working with the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care, the perceived effectiveness of the model, the use and understanding of the model of care and changes in practice attributed to the model of care.

Topic guides for interviews with commissioners of healthcare services in Lambeth and Southwark are designed to elicit perceptions on the motivation for commissioning child health service programmes including the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care, the ambitions for the model of care and the facilitators and barriers to commissioning healthcare services within Lambeth and Southwark.

Analysis of qualitative data will be largely inductive, drawing on the principles of thematic analysis, but informed by the RE-AIM Framework.19 20 Inductive themes will emerge through repeated examination and comparison; tabulation and mapping. In reports, they will be illustrated with anonymised verbatim quotes from participants.

Review of policy documents

Information relating to the context of the trial that may affect the implementation and/or outcomes of the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care will be documented. In addition, a review of policy documents over the duration of the CYPHP trial will take place. Information will be reviewed and relevant information extracted into a timeline. The timeline will be available to consult when results from other sources (both quantitative and qualitative) begin to emerge, to understand patterns appearing in those data over time and between health centres and catchment areas.

Triangulation of data sources

Credibility and validity will be maximised through cross verification and exploration of differences between the outcomes of the various methods. This takes place in four ways:

Maximising validity in analysis of qualitative data within the research team by techniques such as discussing coding, constant comparison, accounting for deviant cases, systematic coding.

Triangulation of interviews with results from the NoMAD questionnaire, exploring and accounting for differences.

Mapping the perspectives of commissioners, service managers, healthcare providers, CYP and caregivers to give a complete view of stakeholder perspectives.

Conducting multiple focus groups sampled from service user, managers and commissioners in different GP clusters.

Ethics and dissemination

This process evaluation has been reviewed by NHS REC Cornwall & Plymouth (17/SW/0275). The study has been registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03461848; pre-results). The results of the study will be disseminated via presentations at local, national and international conferences, peer-reviewed journals and workshops with all stakeholders. The findings of this process evaluation will be crucial for scaling up implementation both within and outside of the boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark, London.

Discussion

Current paediatric healthcare models were developed to deliver acute inpatient and high intensity specialist services rather than high quality care for children with long-term conditions who need multidisciplinary, coordinated and planned care to prevent illness and disease complications and to maximise well-being and developmental potential.7 As a result, integrated care models have been proposed as a solution to improve child health services worldwide.5 Integrated care models have the potential to make an important contribution towards improving child health. Although this hypothesis is plausible and is the basis of a great deal of policy, evidence is still indirect and limited. Therefore, a thorough evaluation of the processes through which such integrated care programmes for CYP are implemented is timely and important.

While we have made every effort to ensure the rigour of the process evaluation, the assessment of fidelity largely relies on self-report through service provider interviews and/or questionnaires. Service providers may be reluctant to talk about unwillingness to deliver intervention components or may not have the skills or be comfortable to rate their own competence. Piloting interview guides has enabled us to improve these procedures to reduce the risk of social desirability bias. Our purposive sampling methods will collect data from an array of participants and ensure data collection will continue until saturation.

A large part of this process evaluation focuses on four tracer conditions to understand the implementation of integrated care models for CYP. These conditions were selected with the intention of designing a generalisable model of care for CYP with common and chronic conditions as part of a health system response to the epidemiological transition to chronic disease. In addition, by selecting four tracer conditions, we will be able to examine the parallels and divergences across a range of conditions, to support us in understanding how integrated care may be applied to a variety of conditions. However, these findings should be treated with caution and applying these findings to other conditions to another should be done cautiously.

Given the complexity of the proposed interventions and the variability in both the target population and service providers, it is challenging to understand the nuances of implementing the CYPHP Evelina London Model of Care. However, by ensuring the inclusion of all stakeholders within the model, we hope to achieve a greater insight into how integrated care can be implemented for CYP. We anticipate that this process evaluation will allow us to provide a comprehensive understanding of how outcomes were achieved by the programme and how to implement programmes and integrated care models of this nature in alternative settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: R-MS was responsible for writing the first draft of the protocol. R-MS, JG, NS, JJN, ME, JF, RL and IW were involved in the study design and in obtaining ethical approvals. RL and IW were responsible for study conception. All authors commented on the manuscript and agreed with the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by Guys and St Thomas Charity, grant number HIF180101KCL.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Claire Lemer, Anto Ingrassia, Michelle Heys

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Wolfe I, Mandeville K, Harrison K, et al. . Child survival in England: strengthening governance for health. Health Policy 2017;121:1131–8. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Viner RM. State of child health: report. London: Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolfe I, Cass H, Thompson MJ, et al. . Improving child health services in the UK: insights from Europe and their implications for the NHS reforms. BMJ 2011;342:d1277 10.1136/bmj.d1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Were WM, Daelmans B, Bhutta Z, et al. . Children’s health priorities and interventions. BMJ 2015;351:h4300 10.1136/bmj.h4300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wolfe I, Thompson M, Gill P, et al. . Health services for children in western Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1224–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62085-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mansfield A. BMA board of Science. Growing up in the UK: ensuring a healthy future for our children BMA. 2013. https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/public-and-population-health/child-health/growing-up-in-the-uk (Accessed 15 Oct 2018).

- 7. Viner RM, Blackburn F, White F, et al. . The impact of out-of-hospital models of care on paediatric emergency department presentations. Arch Dis Child 2018;103:128–36. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Newham JJ, Forman JR, Heys M, et al. . The Children and Young People’s Health Partnership (CYPHP) Evelina London Model of Care: Protocol for an opportunistic cluster randomised evaluation (cRCT) to assess child health outcomes, healthcare quality and health service use. BMJ Open 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organisation. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. . Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:26–33. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. . Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, et al. . Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ 2006;332:413–6. 10.1136/bmj.332.7538.413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research: an overview : Linnan L, Steckler A, Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2002:2–24. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kessler RS, Purcell EP, Glasgow RE, et al. . What does it mean to "employ" the RE-AIM model? Eval Health Prof 2013;36:44–66. 10.1177/0163278712446066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Finch TL, Girling M, May CR, et al. . Improving the normalization of complex interventions: part 2 - validation of the NoMAD instrument for assessing implementation work based on normalization process theory (NPT). BMC Med Res Methodol 2018;18:135 10.1186/s12874-018-0591-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coad J. Using art-based techniques in engaging children and young people in health care consultations and/or research. Journal of Research in Nursing 2007;12:487–97. 10.1177/1744987107081250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. . Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med 2010;8:63 10.1186/1741-7015-8-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mansfield A. BMA board of Science. Growing up in the UK: ensuring a healthy future for our children BMA. 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.