Abstract

Objective

To describe the disposition and sociodemographic characteristics of medical students associated with inclusion of traditional and complementary medicine in medical school curricula in Uganda.

Design

A cross-sectional study conducted during May 2017. A pretested questionnaire was used to collect data. Disposition to include principles of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curricula was determined as proportion and associated factors determined through multivariate logistic regression.

Participants and setting

Medical students in their second to fifth years at the College of Health Sciences, Makerere University, Uganda. Makerere University is the oldest public university in the East African region.

Results

393 of 395 participants responded. About 60% (192/325) of participants recommended inclusion of traditional and complementary medicine principles into medical school curricula in Uganda. The disposition to include traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curricula was not associated with sex, age group or region of origin of the students. However, compared with the second year students, the third (OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.66) and fifth (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.93) year students were significantly less likely to recommend inclusion of traditional and complementary medicine into the medical school curricula. Participants who hold positive attributes and believe in effectiveness of traditional and complementary medicine were statistically significantly more likely to recommend inclusion into the medical school curricula in Uganda.

Conclusions

Inclusion of principles of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curricula to increase knowledge, inform practice and research, and moderate attitudes of physicians towards traditional medicine practice is acceptable by medical students at Makerere University. These findings can inform review of medical schools’ curricula in Uganda.

Keywords: Traditional and complementary medicine, Medical school curricula, Medical students, Makerere University, Uganda

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate the disposition of medical students and their sociodemographic factors associated with intention to include principles of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curricula in Uganda.

More than 70.8% (395/558) of registered medical students enthusiastically participated in the study; no eligible participants available at the time of study declined participation.

The study involved students from only one public medical school; so findings may be systematically different from studies conducted in the newer medical schools.

The cross-sectional nature of the study limits attributing the difference in dispositions to include traditional and complementary medicine by year of study to the effect of time in training and interactions in the medical school.

Background

Worldwide, a significant proportion of patients use traditional and complementary medicines (T&CM) in the treatment of various illnesses. For example, a systematic review of 26 studies done in 13 countries showed that 7%–64% of patients with cancer (average use 31%) use T&CM at some point during their illness.1 In sub-Saharan Africa, a recent systematic review showed a high use of T&CM alone or in combination with conventional medicine. Most of the users were likely to be of low socioeconomic status and low educational attainment. The review also showed that most of the users (55.8%–100%) do not disclose use to healthcare professionals (HCPs).2 In Uganda, T&CM practice is common across a range of illnesses including diabetes, hypertension and cancers. People use T&CM for various reasons including beliefs in intrinsic efficacy, long history of use, and perceived barriers to biomedical care.3–6 It is likely that T&CM use and traditional healing practices will continue side by side with biomedicine for the foreseeable future.7 In addition, the WHO supports the incorporation of T&CM into national health systems and has developed a traditional medicine strategy (2014–2023) that stipulates the importance of and how to integrate traditional medicine into the national biomedical health system. The WHO strategies acknowledge that T&CM of proven quality, safety and efficacy essentially contributes to improving access to care by all people in need.8

The WHO8 9 has described traditional medicine as ‘the sum total of the knowledge, skill and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences traditional to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness’. On the other hand, WHO8 9 describes complementary medicine as: ‘a broad set of healthcare practices that are not part of that country’s own tradition or conventional medicine and are not fully integrated into the dominant healthcare system.’ In this study, T&CM was described as any practices that is not part of conventional medicine (biomedicine), whose philosophical underpinnings are beliefs, customs and experiences traditional to the people concern, and whose aims are maintenance of health, prevention of ill health, determination of causes of ill health and the treatment of diseases and ill health including physical, social and mental disorders. The foregoing descriptions of T&CM do not include issues of evidence for effectiveness or harm of the practices. Evidence-based use of T&CM in combinations with conventional medicine fall in the realm of integrative medicine. In the high-income countries, particularly Canada and USA, a tight working relationship has developed between conventional medicine and traditional medicine practices. This has led to the emergence of a hybrid system of healthcare dispensation, the integrative medicine, which brings together the two practices under one roof. Integrative medicine has variously been defined as ‘a sound combination of safe and effective ancient traditional medicine or complementary medicine, and state-of-the-art conventional medicine’.10 And, ‘an approach to the practice of medicine that makes use of the best available evidence taking into account the whole person (body, mind and spirit), including all aspects of lifestyle. It emphasises the therapeutic relationship and makes use of both conventional and complementary/alternative approaches’.11 In a bid to harmonise integrative medicine practices and derive maximum benefits from both conventional and traditional medicine practices, while minimising harms, a consortium of 57 academic health institutions and health systems in North America have formed an alliance, The Consortium of Academic Health Centers for Integrative Medicine (CAHCIM) to oversee and regulate as well as uphold standards of care and safety. The Consortium has defined integrative medicine as follows: ‘the practice of medicine that reaffirms the importance of the relationship between practitioner and patient, focuses on the whole person, is informed by evidence, and makes use of all appropriate therapeutic approaches, healthcare professionals and disciplines to achieve optimal health and healing’.12 There is a clear common philosophical strand that spans through the above definitions of integrative medicine and traditional medicine; the need to respect the right of the patients and to provide safe, effective and accessible healthcare to the human population.

Regardless of whether patients choose to use T&CM in parallel, interchangeably or in combination with biomedicine, physicians ought to uphold the ethical principles of beneficence and safeguard public welfare among others by providing appropriate management based on best available evidence.13 The duty to prevent harm and protect patients’ welfare demands that HCPs have access to information regarding evidence on efficacious and effective T&CM. Physicians are also obliged to know the harmful effects of T&CM in order to be able to provide appropriate guidance to their patients and the public regarding their healthcare choices.14 Failure of HCPs to advise patients against potentially harmful T&CM is deemed unethical because such patients could get harmed by using the T&CMs.15 Including aspects of T&CM into medical school curricula increases awareness and knowledge of the future clinicians on T&CM, enables the students to understand better the paradigm from which traditional health practitioners (THP) treat their patients and potentially fosters cooperation and collaboration between T&CM practitioners and conventional medicine.16 17 In addition, there is evidence that general knowledge regarding the theories and fundamentals in T&CM practices could help physicians in guiding patients about their health choices.18 To that extent, physicians ought to know about T&CM so they can guide their patients appropriately and ensure safety of use of T&CM alone or in combinations with conventional medicine. This requires that medical schools include principles of T&CM into their curricula, so the medical students could learn about T&CM principles including why T&CM matters, how to talk about it with patients, how/where to access it, how they work and potential side effects, without taking on the expectation of becoming experts in its delivery. The medical schools need not appear to be training the medical students to become T&CM practitioners, a notion that could make the T&CM practitioners feel threatened in their trade and object genuine integration of biomedicine with T&CM. However, there are limited data on the proportions of medical schools in sub-Saharan Africa that teach aspects of T&CM to their medical students. Similarly, there is limited awareness of the disposition of medical students towards the integration of T&CM into medical school curricula in Uganda and most sub-Saharan Africa. Therefore, there is need to determine upfront the proportion and characteristics of medical students who endorse the inclusion of T&CM into the curricula of medical schools. The aim of this study was therefore to understand the attitudes and perceptions of medical students at Makerere University College of Health Sciences (MakCHS) regarding the inclusion of principles of T&CM into the medical school curricula. We also aimed to establish the sociodemographic characteristics of the students who are disposed to inclusion of T&CM into the medical school curricula. These findings can inform policies on the integration of T&CM and biomedical practices in Uganda so that the medical students and physicians (1) become familiar with the epidemiology of use and best available evidence on T&CM (where to find it, how to interpret it) and (2) know how to discuss issues of T&CM with patients in an open and non-judgmental way.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional survey at the School of Medicine, MakCHS. The School of Medicine was started in 1923. It is the oldest medical school in Uganda and admits about 80–100 first year medical students every year. The school has been keen to adopt innovative approaches to training and learning including problem-based learning and community-based education and service to improve learning experience and produce doctors with knowledge and skills that are relevant to demands of the societies they serve.19–22

Study population and period

Participants to this study included all registered Ugandan male and female medical students in the second, third, fourth and fifth years pursuing the degree of bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery (MBChB). The MBChB programme involves 5 years of theoretical and practical training before the successful candidates enrol for a supervised internship practice of 1 year. First year students were excluded from this study on assumption that their views might be very similar to views of the general community and lack the insight that medical students typically have as product of their training and experiences in the training institution. The curriculum of the students involves rotation and training on the wards during the fourth and fifth years of study. Foreign students (n=36) were excluded because their concepts of T&CM could be influenced by the status of practices in their home countries. Data were collected in May 2017, during the week immediately after the end of year university examinations when students were generally available on campus and awaiting the start of the recess semester.

Sampling and recruitment of participants

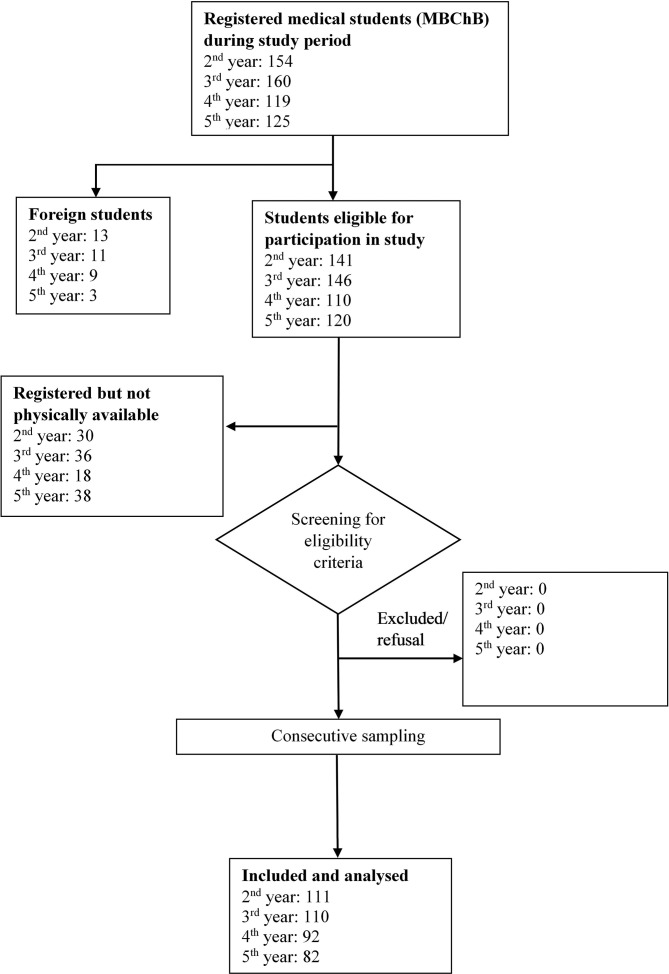

The first author and three research assistants (RA) met with the president of the medical students’ association (Makerere University Medical Students’ Association (MUMSA)) and discussed the objectives and procedures for the study. Thereafter, the president and the RAs met with the class representatives of the second, third, fourth and fifth year students and agreed on the dates and time for interviews for each class. The students were met separately by their year of study in designated lecture theatres following mobilisation by the president and their class representatives. The fifth year students were the first to be interviewed because they would soon leave the University for Internship. Subsequently, the fourth, third and second year students were met, each group on different days. The RAs provided explanations about purpose and objectives of the study to all eligible participants before enrolment. Thereafter, prospective participants were given the study information sheet with detail information on the study including objectives, inclusion criteria, consent procedures and rationale for selection of the specific category of participants. Every registered student present in the meeting who met eligibility criteria was enrolled consecutively into the study (figure 1). Participants were given opportunities to ask questions regarding the study. Individual informed consents were sought from each participant before administration of the questionnaire. No prospective participants declined participation in the study. Participants self-completed the questionnaires and returned them to the RAs through their representatives. Participants who wished to complete their questionnaires from their halls of residents were allowed to return the completed questionnaires the following day and deposit with the MUMSA president. All participants returned their completed questionnaires.

Figure 1.

Study recruitment flow.

Sample size estimation

Sample size estimation was based on the Kish Leslie formula.23 The estimated sample size was 383 students. An a priori decision was made to include all eligible students in second to fifth years of study. Three hundred and ninety-five students were included in the study.

Data collection

The authors did not find published validated tools used for this kind of study in the low-income countries, particularly sub-Saharan Africa. The tool (online supplementary file 1) for this study was therefore developed based on experiences of the investigators and literature regarding traditional medicine, physicians’ knowledge of T&CM and the inclusion of T&CM into medical school curricula. The tool was piloted with 10 medical students from third year; these students were subsequently excluded from participation in the main data collection. The pilot data were reviewed, and the tool was refined before use in the main data collection. The first author (ADM) supervised the RAs during data collection. The students self-administered the questionnaires after provision of written informed consents. Participants were asked about self-use of T&CM, and their disposition towards including T&CM principles into medical school curricula so medical students could understand the basic tenets of T&CM and know how to talk about them with their patients. Attitudes towards effectiveness, safety and usefulness of T&CM were assessed by asking participants questions about T&CM values and utility. For example, participants were asked about self-use and desire for more knowledge on T&CM, willingness to discuss and reactions to issues on T&CM during medical consultations once they have qualified as doctors, whether or not they consider T&CM safe, and perceived value of integrating T&CM with the mainstream national health system.

bmjopen-2019-030316supp001.pdf (79.9KB, pdf)

Data management and analysis

Data was entered on Epi Data, V.3.1 (Epidata software, Odense, Denmark). A biostatistician randomly selected 10% of the questionnaires and independently entered them as part of quality check. There were no significant data entry errors found in the dataset. The full data set was exported into STATA I/C, V.13.1. Analyses included descriptive statistics and determinations of associations between explanatory demographic variables and outcome variables including disposition to include principles of T&CM into medical school curricula. The secondary outcome measure was attitudes towards incorporating T&CM into mainstream biomedicine. The χ2 tests were used to determine associations between the explanatory variables and outcome variables. Unconditional logistic regression models were used to determine magnitudes of associations between explanatory and outcome variables. ORs have been reported with accompanying two-tailed 95% CIs.

Patient and public involvement

There was no direct involvement of patients and the public in this study. However, the motivation for this study was the limited evidence to guide and inform the formulation and implementation of a bill ‘The Indigenous and Complementary Medicine Bill 2015’ in the Parliament of the Republic of Uganda. Findings from this study was shared with members of the Parliamentary Committee on Health on 23 May 2018 during a session to gather evidence to formulate the Bill into a law.

Results

Study participants

Of 395 participants invited, 393 (99.5%) responded. The distribution of students who responded by year of study were relatively comparable: second year (25.8%; n=98), third year (28.9%; n=110), fourth year (23.9%; n=91) and fifth year (21.3%; n=81). Majority of participants were male (70.5%; n=277) and aged 23–26 years (50.5%, n=277) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics by year of study

| Variable | Year of study, N (%) | ||||

| Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Total | |

| Age group (years) | 98 | 110 | 91 | 81 | 380 |

| 19–22 | 77 (56.2) | 51 (37.2) | 6 (4.4) | 3 (2.2) | 137 |

| 23–26 | 14 (7.3) | 42 (21.9) | 68 (35.4) | 68 (35.4) | 192 |

| ≥27 | 7 (13.7) | 17 (33.3) | 17 (33.3) | 10 (19.6) | 51 |

| Missing | 13 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 17 |

| Gender | 104 | 109 | 92 | 82 | 393 |

| Male | 71 (25.6) | 76 (27.4) | 70 (25.3) | 60 (21.7) | 277 |

| Female | 37 (31.9) | 35 (30.1) | 22 (19.0) | 22 (19.0) | 116 |

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| Region of origin | 111 | 110 | 92 | 84 | 387 |

| Northern | 6 (23.1) | 5 (19.2) | 9 (34.6) | 6 (23.1) | 26 |

| North Eastern | 2 (16.7) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) | 4 (33.3) | 12 |

| Eastern | 16 (21.9) | 22 (30.1) | 22 (30.1) | 13 (17.8) | 73 |

| West Nile | 4 (28.6) | 2 (14.3) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (14.2) | 14 |

| Mid-Western | 9 (27.3) | 12 (36.4) | 7 (21.2) | 5 (15.2) | 33 |

| South Western | 19 (36.5) | 19 (36.5) | 6 (11.5) | 8 (15.4) | 52 |

| Central | 48 (28.7) | 43 (25.8) | 35 (21.0) | 41 (24.6) | 167 |

| Missing | 0 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

Inclusion of T&CM into medical school curricula

More than half of the participants (59.1%; 192/325) wished that theories and principles of T&CM be included in the medical school curricula in Uganda. On adjusting for sex, age and region of origin, the third (OR 0.34; 95% CI 0.17 to 0.66) and fifth (OR 0.39; 95% CI 0.16 to 0.93) year medical students were statistically significantly less likely to desire the inclusion of T&CM into medical school curricula as compared with the second year medical students. There was no statistically significant difference in the disposition to include T&CM into the curricula by gender, age groups and region of origin (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and disposition to include traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) theories and principles into medical school curricula

| Demographic variables N (%) |

Integrate T&CM into the medical school curricula | OR | ||

| Yes, N | No, N (%) | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex, n=314 | 193 | 134 | ||

| Male | 138 (58.2) | 99 (41.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 55 (61.1) | 35 (38.9) | 1.13 (0.69 to 1.85) | 1.07 (0.62 to 1.87) |

| Age group (years), n=322 | 187 | 127 | ||

| 19–22 | 68 (60.2) | 45 (39.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–26 | 96 (61.1) | 61 (38.9) | 1.04 (0.63 to 1.71) | 1.55 (0.77 to 3.11) |

| ≥27 | 23 (52.3) | 21 (47.7) | 0.72 (0.36 to 1.46) | 1.07 (0.47 to 2.45) |

| Years of study, n=325 | 192 | 133 | ||

| Second | 67 (71.3) | 27 (28.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Third | 44 (46.3) | 51 (53.7) | 0.35 (0.19 to 0.63) | 0.34 (0.17 to 0.66) |

| Fourth | 45 (63.4) | 26 (36.6) | 0.70 (0.36 to 1.35) | 0.62 (0.26 to 1.43) |

| Fifth | 36 (55.4) | 29 (44.6) | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.97) | 0.39 (0.16 to 0.93) |

| Region of origin of student, n=325 | 189 | 132 | ||

| Northern | 15 (62.5) | 9 (37.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| North Eastern | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 0.48 (0.12 to 1.93) | 0.54 (0.12 to 2.37) |

| Eastern | 28 (50.9) | 27 (49.1) | 0.71 (0.28 to 1.85) | 0.76 (0.27 to 2.10) |

| West Nile | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2.00 (0.33 to 11.97) | 1.69 (0.25 to 11.40) |

| Mid-Western | 18 (9.3) | 10 (7.3) | 1.2 (0.39 to 3.65) | 1.33 (0.41 to 4.28) |

| South Western | 25 (56.8) | 19 (43.2) | 0.83 (0.31 to 2.25) | 1.09 (0.37 to 3.19) |

| Central | 90 (62.5) | 54 (37.5) | 1.10 (0.46 to 2.63) | 1.29 (0.51 to 3.27) |

| Missing | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.4 (0.08 to 2.06) | 0.35 (0.05 to 2.36) |

Adjustment done for demographic factors in the table. Bold face indicates statistically significant findings.

Attitudes and perceived values of T&CMs

More than half of the participants reported ever using T&CM for various ailments (59.6%; 192/322), while about two-thirds (63.9%; 185/291) would want to know more about T&CM. The odds of recommending inclusion of principles of T&CM into the medical school curricula in Uganda was statistically significantly greater among participants who affirmed positive attributes to T&CM compared with participants who did not believe in the effectiveness of T&CM. For example, on adjusting for age, sex, year of study and region of origin, participants who reported self-use of T&CM (OR 2.01; 95% CI 1.16 to 3.44) wanted to know more about T&CM (OR 19.68; 95% CI 7.58 to 51.13), willing to discuss T&CM with patients (OR 25.72; 95% CI 11.75 to 56.30) and willing to refer patients to T&CM practitioners (OR 12.70; 95% CI 5.12 to 31.46) were statistically significantly more likely to recommend integration of T&CM principles into medical school curricula compared with those who never used T&CM, never wanted to know more about T&CM, not willing to discuss issues of T&CM with their patients and not in disposition to refer patients to T&CM practitioners once in practice, respectively (table 3). On the other hand, there was consistently lower odds of wishing to include T&CM into medical school curricula by participants who affirmed negative attributes including that ‘encouraging use of T&CM is detrimental to public health’ (OR 0.17; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.33) and ‘there is no estimable benefits of using T&CM’ (OR 0.13; 95% CI 0.07 to 0.25) as compared with participants who thought T&CM was useful to the population and has definite health benefits (table 3).

Table 3.

Disposition to traditional and complementary medicines (T&CM)

| Explanatory variables N (%) | Integrate T&CM in the medical school curricula | OR | ||

| Yes, N | No, N | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

| Self-use of T&CM (Ever), n=322 | 192 | 130 | ||

| Yes | 142 (63.7) | 81 (36.3) | 1.72 (1.06 to 2.77) | 2.01 (1.16 to 3.44) |

| No | 50 (50.5) | 49 (49.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Wants to know more about T&CM, n=291 | 185 | 106 | ||

| Yes | 179 (73.1) | 66 (26.9) | 18.08 (7.32 to 44.6) | 19.68 (7.58 to 51.13) |

| No | 6 (13.0) | 40 (87.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Integrate practice of T&CM into mainstream biomedicine, n=286 | 175 | 111 | ||

| Yes | 168 (88.9) | 21 (11.1) | 102.9 (42.11 to 251.2) | 179.3 (57.4 to 560.1) |

| No | 7 (7.2) | 90 (92.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Willingness to refer to T&CM practitioners, n=271 | 150 | 121 | ||

| Yes | 69 (90.8) | 7 (9.2) | 13.87 (6.06 to 31.75) | 12.70 (5.12 to 31.46) |

| No | 81 (41.5) | 114 (58.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Willingness to discuss T&CM with patients, n=293 | 176 | 117 | ||

| Yes | 166 (76.7) | 45 (21.3) | 26.56 (12.69 to 55.61) | 25.72 (11.75 to 56.3) |

| No | 10 (12.2) | 72 (87.8) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| There are no estimable benefits of T&CM, n=271 | 161 | 110 | ||

| Yes | 26 (30.6) | 59 (69.4) | 0.17 (0.09 to 0.29) | 0.13 (0.07 to 0.25) |

| No | 135 (72.6) | 51 (27.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Encouraging use of T&CM at biomedical facilities poses threat to public health, n=262 | 148 | 109 | ||

| Yes | 46 (40.0) | 69 (60.0) | 0.26 (0.16 to 0.44) | 0.17 (0.09 to 0.33) |

| No | 102 (71.8) | 40 (28.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, region of origin of students and year of study at medical school.

Incorporating T&CM practices into the national health system

Two-thirds (66.9%; 218/326) of participants endorsed integrating principles and practices of T&CM into the national health system. However, participants in third year were less likely to desire incorporation of T&CM practices into the mainstream national health system (OR 0.40; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.80) as compared with the second year students who had not yet had clinical exposure during their training in the medical school. This association was not statistically significant for the fourth and fifth year medical students. Age and gender were not statistically significantly associated with the disposition to integrate T&CM into the mainstream national health system (table 4).

Table 4.

Disposition to integrate traditional and complementary (T&CM) medicine practice into mainstream medicine

| Demographic variables | Integrate T&CM into the national health system | OR | ||

| Yes, N | No, N | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex, n=328 | 219 | 109 | ||

| Male | 149 (63.9) | 84 (36.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 70 (73.7) | 25 (26.3) | 1.58 (0.93 to 2.68) | 1.67 (0.92 to 3.03) |

| Age group (years), n=314 | 209 | 105 | ||

| 19–22 | 74 (64.4) | 41 (35.6) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 23–26 | 105 (67.7) | 50 (32.3) | 1.16 (0.70 to 1.94) | 1.68 (0.82 to 3.44) |

| ≥27 | 30 (68.2) | 14 (31.8) | 1.19 (0.57 to 2.49) | 1.61 (0.68 to 3.84) |

| Years of study, n=326 | 218 | 108 | ||

| Second | 71 (75.5) | 23 (24.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| third | 51 (54.8) | 42 (45.2) | 0.39 (0.21 to 0.73) | 0.40 (0.20 to 0.80) |

| fourth | 53 (72.6) | 20 (27.4) | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.72) | 0.77 (0.31 to 1.89) |

| fifth | 43 (65.2) | 23 (34.8) | 0.61 (0.30 to 1.21) | 0.45 (0.18 to 1.10) |

| Region of origin of student, n=322 | 215 | 107 | ||

| Northern | 14 (58.3) | 10 (41.7) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| North Eastern | 6 (54.6) | 5 (45.4) | 0.85 (0.20 to 3.61) | 0.95 (0.22 to 4.13) |

| Eastern | 39 (66.1) | 20 (33.9) | 1.39 (0.53 to 3.69) | 1.42 (0.51 to 3.92) |

| West Nile | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | 3.57 (0.64 to 19.97) | 3.05 (0.50 to 8.40) |

| Mid-Western | 16 (64.0) | 9 (36.0) | 1.27 (0.40 to 4.02) | 1.42 (0.43 to 4.67) |

| South Western | 23 (62.2) | 14 (37.8) | 1.17 (0.41 to 3.35) | 1.34 (0.44 to 4.07) |

| Central | 105 (71.4) | 42 (28.6) | 1.79 (0.74 to 4.33) | 2.05 (0.81 to 5.16) |

| Missing | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.29 (0.05 to 1.78) | 0.38 (0.06 to 2.61) |

*Adjusted for the demographic factors included in the table.

Discussion

The main aims of this study were to quantify the disposition to include principles of T&CM into medical school curricula and to determine factors that are associated with the disposition among preclinical and clinical year students at the oldest medical school in Uganda. In addition, we also sought to determine attitudes of the students towards integration of T&CM into mainstream national health services. We found that two-thirds of medical students considered it necessary to include T&CM principles into the medical school curricula in Uganda. More than half of the participants also reported self-use of T&CM, wanted to learn more about T&CM as well as wished to have T&CM integrated into the national health system of Uganda. However, up to 60% (161/271) of the students also noted that the issue of T&CM needs to be handled with caution because it is difficult to estimate the benefits and harms that may arise from using T&CM. These findings support the need to conduct similar studies with government regulatory bodies including the Medical and Dental Practitioners Council and ministry of health officials to determine their disposition in order to inform the process of curricula review and the integration of T&CM and biomedicine into one national health system. Our qualitative study that preceded this study revealed some ethical and operational challenges that need to be addressed before and during integration.24 Drawing from both this study and our earlier qualitative study with medical students, their faculty and the THPs, there is a clear need to equip the medical students and healthcare professionals with critical knowledge and approaches to T&CM practice in order to enable them communicate better with their patients who often use T&CM modalities. Health sciences students in South Africa, Sierra Leone, the Middle East and Asia have similarly reported the importance of learning about T&CM in their medical practices.25–29 Empowering healthcare professionals with the tools to talk to their patients and find/use evidence-based resources could potentially minimise patients’ delay in health seeking due to fear of being rebuked by the healthcare professionals for using T&CMs.

Medical students do not need to be trained to practice T&CM, but rather to know about and become aware of the paradigm from which T&CM practitioners do their healing. Biomedical and THPs who currently have inadequate knowledge of what each other do could then work side by side in an integrated national health system with clear regulations to guide and control practices. Hitherto, there are two parallel health systems in Uganda: the dominant biomedical national health system and the traditional health practices that are often sought covertly. Having two parallel health systems potentially contributes to delay in seeking medical care if patients choose to seek help alternately rather than concurrently. For example, a study among patients with breast cancer in Indonesia showed that use of traditional medicine before conventional medicine health seeking and after cancer diagnoses led to delay and advanced stage cancers at diagnoses and missing of treatment schedules, respectively.30 Similarly, in Malaysia, patients with cancer who visited THPs before seeking care at medical facilities experienced increased time to diagnosis and hence advanced stage cancers at diagnoses.31 To avoid the tendency for delay in health seeking, it could be prudent for states, especially those in the low-income countries where patients seek care in series/alternately to adopt the strategies advocated and outlined by WHO regarding the integration of T&CM into their national health systems.8 32 In this way, patients could find both systems of care within the same vicinity. An important step in the integration of T&CM with conventional medicine is training of medical students on aspects of T&CM and training of the T&CM practitioners on critical aspects of biomedicine, including infection control approaches, immunisation, how to avoid risk factors for diseases and adopting healthy behaviours. Medical students need principles of T&CM in their curricula to improve their awareness about T&CM, enable them communicate competently with their patients regarding T&CM use and to enable them refer patients when appropriate to THPs.33

In this study, the medical students who considered that objectively estimating the benefits and harms from T&CM was difficult, and those who thought that endorsing use of T&CM would pose threat to public health were more cautious regarding intention to include T&CM into medical school curricula. To this end, HCPs need to engage more vigorously in researches involving T&CM in order to accumulate evidence for effectiveness and safety of T&CM for guiding informed consents and healthcare choices.13 Medical students need to be taught T&CM and encouraged to engage in research involving T&CM in order to reduce gaps in knowledge that physicians have on common T&CMs.34 Studies have shown that many physicians not only lack knowledge on T&CM but also hold the potentially erroneous beliefs that T&CM are not proven to be effective and can be harmful to humans. In Jordan, up to 80% and 70% of Jordanian physicians reported that T&CM are not evidence based and could cause harm to patients.35 The belief among physicians that T&CM is ‘not evidence-based’ treatment was also reported in a nationwide survey in Japan, where nearly 82% of 751 surveyed oncologists believed that T&CM was ineffective because of lack of reliable scientific evidence.36 Even in the USA where a number of medical schools have already included aspects of T&CM in their integrative medicine curricula, a survey of 705 physicians in Colorado showed that only few physicians thought they had adequate knowledge about T&CM to allow them provide factual information to their patients for use or non-use. The majority of the surveyed physicians reported that they needed to learn more about T&CM in order to competently address patients’ concerns.37 It is therefore critical to include T&CM into medical school curricula.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that potentially restrict interpretations and generalisation of the findings; only one medical school was included in the study. The uniqueness of Makerere University School of Medicine including its position as the oldest and most famous medical school in the region could limit utility of our findings. However, the national nature and universal mix of students and faculty at this university could mean that opinion and experiences from all over the country and perhaps region are represented and therefore increase the likelihood that findings from other medical schools could be similar to our findings. This argument is supported by our data which showed that the disposition to include principles of T&CM into medical school curricula and to integrate T&CM with the national health system was not influenced by the region of Uganda where the students originated. Second, the tool for data collection was not validated, and this could import some constructs and reliability bias. Pilot testing was done to ameliorate these bias. However, future studies could develop and validate a culture and context sensitive tool similar to the Integrative Medicine Attitude Questionnaire38 for use in the low-income countries. Other potential limitations are volunteer bias and the male dominance among the study participants. However, this is unlikely to have influenced our findings because sex was not statistically significantly associated with the disposition to include T&CM into the medical school curricula. In addition, most medical schools in Uganda have a male predominance. Therefore, our sample could be representative of the general population of medical schools in Uganda and generalisability of findings could be appropriate. Again, volunteer bias is unlikely to have played a role in this study because participation was generally high with 99.5% participation rate (393 of 395 invited students participated). There were no students who declined to participate.

Conclusion

Medical students support inclusion of T&CM principles into medical school curriculum and the national health system in Uganda. Including T&CM in medical school curricula increases awareness and knowledge of the future clinicians on T&CM, potentially fosters cooperation and collaboration between T&CM practitioners and biomedicine and helps the students understand better the paradigm from which THPs treat their patients.16 17 Third and fifth year medical students were less enthusiastic regarding inclusion of T&CM into medical school curricula mainly because of challenges involved in estimating benefits and harms from T&CM and the potential harms to individual and public health that T&CM pose.24

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the study participants whose active involvement and participation has made this study a success. The authors are also indebted to the research assistants who collected data, and to Mr. Edward Were Maloba who participated in the data analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: ADM contributed to the acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript and statistical expertise. ADM, CI and GT contributed to the study concept and design. ADM and SV contributed to the analysis of data. ADM, CI and COG supervised the study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content and final approval of the submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study protocol was approved by the Makerere University School of Social Sciences Research and Ethics Committee (MakSSSREC), number MAKSS REC01.17.013. Authority to interact with and interview medical students was obtained from the Principal, College of Health Sciences, Makerere University. Each study participant was provided detail information about the study including study purpose and procedures. All participants provided written informed consents before participating in the study. Data from the study has been anonymized and protected from reach of any unauthorized persons to uphold privacy and confidentiality. Participants received a token of $2.50 as transport refund.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Ernst E. The prevalence of complementary/Alternative medicine in cancer. Cancer 1998;83:777–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. James PB, Wardle J, Steel A, et al. . Traditional, complementary and alternative medicine use in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000895 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abbo C, Ekblad S, Waako P, et al. . The prevalence and severity of mental illnesses handled by traditional healers in two districts in Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2009;9:16–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rutebemberwa E, Lubega M, Katureebe SK, et al. . Use of traditional medicine for the treatment of diabetes in eastern Uganda: a qualitative exploration of reasons for choice. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:1 10.1186/1472-698X-13-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mwaka AD, Okello ES, Orach CG. Barriers to biomedical care and use of traditional medicines for treatment of cervical cancer: an exploratory qualitative study in northern Uganda. Eur J Cancer Care 2015;24:503-13 10.1111/ecc.12211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nuwaha F, Musinguzi G. Use of alternative medicine for hypertension in Buikwe and Mukono districts of Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:301 10.1186/1472-6882-13-301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pinkoane MG, Greeff M, Koen MP. Policy makers' perceptions and attitudes regarding incorporation of traditional healers into the National health care delivery system. Curationis 2008;31:4–12. 10.4102/curationis.v31i4.1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO Who traditional medicine strategy: 2014-2023. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/92455/1/9789241506090_eng.pdf?ua=1 2013

- 9. WHO Traditional medicine strategy 2002–2005. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sundberg T, Hök J, Finer D, et al. . Evidence-Informed integrative care systems—The way forward. Eur J Integr Med 2014;6:12–20. 10.1016/j.eujim.2013.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kligler B, Maizes V, Schachter S, et al. . Core competencies in integrative medicine for medical school curricula: a proposal. Acad Med 2004;79:521–31. 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kligler B, Chesney M. Academic health centers and the growth of integrative medicine. JNCI Monographs 2014;2014:292–3. 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgu039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vohra S, Cohen MH. Ethics of complementary and alternative medicine use in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54:875–84. 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Adams KE, Cohen MH, Eisenberg D, et al. . Ethical considerations of complementary and alternative medical therapies in conventional medical settings. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:660–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-8-200210150-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ernst E. Ethics and complementary and alternative medicine. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:940–40. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Milan FB, Landau C, Murphy DR, et al. . Teaching residents about complementary and alternative medicine in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:562–7. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00168.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chitindingu E, George G, Gow J. A review of the integration of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine into the curriculum of South African medical schools. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:40 10.1186/1472-6920-14-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaster B, Unterborn JN, Scott RB, et al. . What should students learn about complementary and alternative medicine? Acad Med 2007;82:934–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318149eb56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaye DK, Muhwezi WW, Kasozi AN, et al. . Lessons learnt from comprehensive evaluation of community-based education in Uganda: a proposal for an ideal model community-based education for health professional training institutions. BMC Med Educ 2011;11:7 10.1186/1472-6920-11-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaye DK, Mwanika A, Sekimpi P, et al. . Perceptions of newly admitted undergraduate medical students on experiential training on community placements and working in rural areas of Uganda. BMC Med Educ 2010;10:47 10.1186/1472-6920-10-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chang LW, Kaye D, Muhwezi WW, et al. . Perceptions and valuation of a community-based education and service (COBES) program in Uganda. Med Teach 2011;33:e9–15. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.530317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mwanika A, Okullo I, Kaye DK, et al. . Perception and valuations of community-based education and service by alumni at Makerere University College of health sciences. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2011;11 Suppl 1:S5 10.1186/1472-698X-11-S1-S5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leslie K. Survey Sampling: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mwaka AD, Tusabe G, Orach Garimoi C, et al. . Turning a blind eye and a deaf ear to traditional and complementary medicine practice does not make it go away: a qualitative study exploring perceptions and attitudes of stakeholders towards the integration of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curriculum in Uganda. BMC Med Educ 2018;18:310 10.1186/s12909-018-1419-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Majeed K, Mahmud H, Khawaja HR, et al. . Complementary and alternative medicine: perceptions of medical students from Pakistan. Med Educ Online 2007;12:4469 10.3402/meo.v12i.4469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hasan SS, Yong CS, Babar MG, et al. . Understanding, perceptions and self-use of complementary and alternative medicine (cam) among Malaysian pharmacy students. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;11:1472–6882. 10.1186/1472-6882-11-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. James PB, Bah AJ, Kondorvoh IM. Exploring self-use, attitude and interest to study complementary and alternative medicine (cam) among final year undergraduate medical, pharmacy and nursing students in Sierra Leone: a comparative study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:121 10.1186/s12906-016-1102-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alzahrani SH, Bashawri J, Salawati EM, et al. . Knowledge and attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine among senior medical students in King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2016;2016:1–7. 10.1155/2016/9370721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yeo ASH, Yeo JCH, Yeo C, et al. . Perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine amongst medical students in Singapore--a survey. Acupunct Med 2005;23:19–26. 10.1136/aim.23.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iskandarsyah A, de Klerk C, Suardi DR, et al. . Consulting a traditional healer and negative illness perceptions are associated with non-adherence to treatment in Indonesian women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2014;23:1118–24. 10.1002/pon.3534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Merriam S, Muhamad M. Roles traditional healers play in cancer treatment in Malaysia: implications for health promotion and education. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013;14:3593–601. 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.6.3593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. WHO Who traditional medicine strategy 2002–2005. Available: http://herbalnet.healthrepository.org/bitstream/123456789/2028/1/WHO_traditional_medicine_strategy_2002-2005.pdf 2002

- 33. Joyce P, Wardle J, Zaslawski C. Medical student attitudes towards complementary and alternative medicine (cam) in medical education: a critical review. J Complement Integr Med 2016;13 10.1515/jcim-2014-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schofield P, Diggens J, Charleson C, et al. . Effectively discussing complementary and alternative medicine in a conventional oncology setting: communication recommendations for clinicians. Patient Educ Couns 2010;79:143–51. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Al-Omari A, Al-Qudimat M, Abu Hmaidan A, et al. . Perception and attitude of Jordanian physicians towards complementary and alternative medicine (cam) use in oncology. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2013;19:70–6. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hyodo I, Eguchi K, Nishina T, et al. . Perceptions and attitudes of clinical oncologists on complementary and alternative medicine: a nationwide survey in Japan. Cancer 2003;97:2861–8. 10.1002/cncr.11402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Corbin Winslow L, Shapiro H. Physicians want education about complementary and alternative medicine to enhance communication with their patients. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1176–81. 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Flaherty G, Fitzgibbon J, Cantillon P. Attitudes of medical students toward the practice and teaching of integrative medicine. J Integr Med 2015;13:412–5. 10.1016/S2095-4964(15)60206-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030316supp001.pdf (79.9KB, pdf)