Abstract

Objective and setting

Primary prevention, comprising patient-oriented and environmental interventions, is considered to be one of the best ways to reduce violence in the emergency department (ED). We assessed the impact of a comprehensive prevention programme aimed at preventing incivility and verbal violence against healthcare professionals working in the ophthalmology ED (OED) of a university hospital.

Intervention

The programme was designed to address long waiting times and lack of information. It combined a computerised triage algorithm linked to a waiting room patient call system, signage to assist patients to navigate in the OED, educational messages broadcast in the waiting room, presence of a mediator and video surveillance.

Participants

All patients admitted to the OED and those accompanying them.

Design

Single-centre prospective interrupted time-series study conducted over 18 months.

Primary outcome

Violent acts self-reported by healthcare workers committed by patients or those accompanying them against healthcare workers.

Secondary outcomes

Waiting time and length of stay.

Results

There were a total of 22 107 admissions, including 272 (1.4%) with at least one act of violence reported by the healthcare workers. Almost all acts of violence were incivility or verbal harassment. The rate of violence significantly decreased from the pre-intervention to the intervention period (24.8, 95% CI 20.0 to 29.5, to 9.5, 95% CI 8.0 to 10.9, acts per 1000 admissions, p<0.001). An immediate 53% decrease in the violence rate (incidence rate ratio=0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.82, p=0.0121) was observed in the first month of the intervention period, after implementation of the triage algorithm.

Conclusion

A comprehensive prevention programme targeting patients and environment can reduce self-reported incivility and verbal violence against healthcare workers in an OED.

Trial registration number

Keywords: health services research, time-series study, healthcare workers, violence

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The comprehensive primary prevention programme integrated components that were environment (signage) and patient-oriented (organisational, educational, relational and security).

A segmented regression analysis was conducted to detect whether the programme had a greater effect than an underlying secular trend.

The primary outcome was self-reported acts of violence, which is subjective.

To limit variation in self-reporting practices, the researchers met monthly with the ophthalmology emergency department (OED) team to discuss the importance of reporting each act of violence from the least (incivility) to most severe (assault).

The generalisation of the results is limited by the single-centre study design and the differences between the OEDs and general EDs.

Introduction

According to the International Labour Office, workplace violence is a frequent phenomenon.1 Hospital healthcare workers are particularly vulnerable by their exposure to patients who can be agitated and distressed.2–4 Around the world, emergency departments (EDs) have been identified as an area of the healthcare sector with a high number of reported violent acts.5–11 However, the phenomenon is under-reported, especially non-physical violence (ie, incivility, harassment and verbal violence). Comparison of self-reported and documentation of hospital incidents in the USA showed that 88% of the events were not documented.12 Such events were mainly informally reported to colleagues.13

Four levels of aggressiveness, in order of severity, are distinguished by the French National Observatory of Violence in Healthcare to describe violent behaviour: incivility (a lack of respect for others that manifests itself as relatively harmless acts), verbal harassment, physical threat (insults and threatening behaviour) and physically violent acts.14 This violence can have repercussions on the physical and emotional health of the victims, and thus on their well-being and the quality of their work. Healthcare workers have been shown to suffer emotional symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder, job dissatisfaction and early feelings of burnout, while hospitals have to bear the financial burden of decreased productivity.15–19

In the ED, the frequency of visits observed in recent years has been accompanied by a drastic increase in waiting times,20 that can lead to a high level of patient dissatisfaction and of aggression towards healthcare workers. Other factors such as anxiety, boredom, lack of information and lack of understanding of triage categories, may also favour violent behaviour.21 22

According to the Haddon matrix adapted by Gates et al, interventions to reduce violence in the ED can be categorised according to the time of their implementation: before (primary prevention), during (secondary prevention) or after (tertiary prevention) an act of violence; and according to their target (healthcare workers, patients or accompanying visitors, and environment).23 24 There are several solutions for the prevention of ED violence. Many interventions have concerned primary prevention with interventions aiming at reducing waiting times, managing priorities (implementation of a triage algorithm to manage patients according to the seriousness of the cases), and improving signage and patients’ understanding of the care pathway.25 26 Security of premises (security guards, video surveillance, warning systems, etc) could sometimes be implemented.7 The few studies that have attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention interventions provide a low level of evidence.24 27

In the ophthalmology ED (OED) of a French university hospital, the healthcare workers reported the occurrence of acts of incivility and verbal violence with both medical and nursing staff, demanding that this issue be addressed.28 The solutions identified to deal with violence included reducing waiting times, improving the premises (ie, the comfort of waiting rooms and confidentiality at the registration desk), changing signage, improving patient information and mediation. These components were integrated into a comprehensive primary prevention programme aimed at averting violence through different components that were environment and patient-oriented. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of this prevention programme on acts of incivility and verbal violence against healthcare workers in the OED.

Methods

Study design

The study was designed as a single-centre, prospective interrupted time-series study. There were three periods: a 3-month pre-interventional period (from 01 January 2014 to 30 March 2014), a 3-month training period (from 31 March 2014 to 09 July 2014) and a 12-month implementation period of the prevention programme (from 10 July 2014 to 30 June 2015); the protocol has been previously published.29

Deviations from the published protocol 23: The planned study design was a ‘on–off’ study over 24 months (including a 2-month pre-interventional period and a 22-month intervention period, without a training period). The first 6 months of the study were not taken into account owing to strong under-reporting of violent acts by the healthcare workers, as ascertained during study coordination meetings. To meet the study schedule, we reduced the duration of the study to 18 months and we modified the study design. We chose to abandon the ‘on–off’ design because of time constraints and the low acceptability of the ‘off’ period when the intervention was to be removed.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in this work.

Setting

This study took place at an adult OED of a university hospital located in an urban environment, in the Rhône-Alpes region of France. The OED is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (24/7), and handles all types of medical and surgical ophthalmological emergencies. In 2014, the department treated 20 309 patients with an average of 68 admissions per day.

Participants

Patients and those accompanying them

All patients (adults and children) registering at the OED from 01 January 2014 to 30 June 2015 were included. Those accompanying the patient (family, friends, etc) were also included. Patients registering during weekends were excluded owing to the organisational characteristics of these periods (ie, different and fewer staff as compared with weekdays), as were those registering during the 3-month training period from 31 March 2014 to 09 July 2014.

Healthcare workers

The OED team (seven nurses, six ward aides, two orthoptic students, seven residents in ophthalmology and four senior ophthalmologists) operating on a rotating schedule to provide care 24/7 was included in the study. The OED team present during a weekday was composed of four nurses, four ward aides, two orthoptic students, one or two residents in ophthalmology and one on-call senior ophthalmologist; this did not change over the study period. Four admitting clerks were also included.

Prevention programme

Programme elaboration

The OED team partnered with researchers to develop a comprehensive prevention programme. The programme had five complementary components, identified through a literature review, that were added progressively.

An organisational component (A), beginning 30 March 2014, with the use by reception nurses of a computerised triage algorithm. This algorithm made it possible to prioritise patients as soon as they arrived in the unit and to carry out initial examinations (such as dilatation of the pupils by the orthoptist) according to the patient’s reason for presentation to the OED. It was linked to a waiting room patient call system. A 3-month phase of training to use of the algorithm was conducted for reception nurses (named ‘training period’). This training period was not planned in the published protocol.29

An environmental component (B) and an educational component (C), beginning 06 October 2014, were combined. The environmental component was signage to help patients to navigate within the OED. The educational component was messages about the OED team and its activity, the care pathway, the patients’ order of passage according to severity and information on the waiting time that were broadcast on a TV in the waiting rooms to patients. As both components addressed difficulties for the patients to understand the functioning of the OED, we considered it appropriate to combine them. This is a deviation from the initial protocol.29

A relational component (D), beginning 05 January 2015, with the presence of a mediator in the OED, for preventive mediation actions. The mediator held a Master’s degree in mediation, and was recruited as part of the project. The mediator was to intervene when patients showed signs of impatience or nervousness and in case of conflict involving a patient or visitor. The mediator circulated through corridors and waiting rooms, and was available to patients and visitors.

A security component (E), beginning 06 April 2015, with the implementation of video surveillance cameras throughout the OED (admissions desk and corridors) connected to the hospital security control room.

Programme implementation

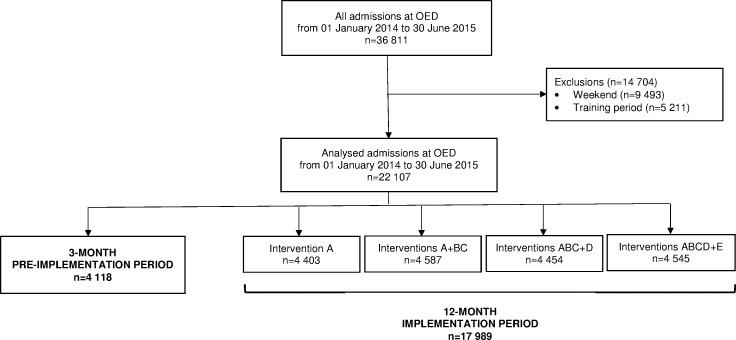

The prevention programme was implemented in four steps, each corresponding to a period of 3 months, after a 3-month training period for the computerised triage algorithm (figure 1). The study project manager conducted monthly visits to the OED during the intervention period to ensure programme implementation.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart of admissions at ophthalmology emergency department (OED). Components: A, computerised triage algorithm; BC, signage and messages broadcast on TV in the waiting rooms; D, mediator; E, video surveillance.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was violence committed by patients or those accompanying them against healthcare workers or against other patients and those accompanying them among all admissions to the OED.

Violence was reported in medical records by healthcare workers. They could report incidents directly committed against them or against patients and those accompanying them. Violence was described using a classification that distinguishes four levels, from the least (incivility) to most severe (assault), based on the French National Observatory of Violence in Healthcare (table 1).29 Clinical cases were used monthly to train professionals to identify the different types of acts of violence to be reported and their level of severity (see table 1 for examples). They were developed from situations experienced by OED professionals. These situations were identified during interviews with OED professionals conducted by the researchers prior to the initiation of the study.28 The aim was to reduce the variability in the classification of events.

Table 1.

Four levels of violence, from the least to most severe, according to the National Observatory of Violence in Healthcare and examples of clinical cases used to train healthcare workers to report acts of violence.

| Level 1 (incivility) |

Insistent questions, incivility, rudeness, occupation of the corridor, spitting and making noise (telephone, etc) Examples:

|

| Level 2 (verbal harassment) |

Insult or verbal abuse without threat Examples:

|

| Level 3 (threat) |

Verbal or physical threat Examples:

|

| Level 4 (assault) |

Intentional violence, assault, vandalism or damage to equipment Examples:

|

The project manager also met monthly with the OED team to discuss the importance of reporting events to limit under-reporting of acts of violence.

Secondary outcomes were waiting time (defined as the interval of time between the administrative registration of the patient and the assessment by a nurse or an ophthalmologist) and length of stay (defined as the interval of time between registration and discharge). This information was routinely collected at the OED for all inpatients.

Blinding

Healthcare workers and patients were not blinded to the intervention period. However, in the absence of individual information on the study (this was not required by the Institutional Review Board), it appeared unlikely that patient behaviour was influenced by the research.

Sample size

In the initial protocol, the sample size was determined for an on–off design by the expected efficacy of each of the five components of the prevention programme. The statistical unit was the patient admitted to the OED. Based on the initial hypotheses, the total sample size required was 30 224 admissions with a risk alpha of 5% and the statistical power of 80%. We did not recalculate the number of subjects required; there is usually no estimation of the sample size in interrupted time-series studies.30 31

Statistical methods

The analyses were conducted on data obtained during the 15-month study period (that corresponded to the pre-intervention and intervention periods, without consideration of the training period). The proportion of admissions with violence committed by patients, or those accompanying them, was expressed as a rate per 1000 admissions. When the perpetrator was someone accompanying the patient, the violence was attributed to the patient.

For all outcomes, we conducted a pre–post analysis to compare rates before and during the implementation of the prevention programme using the χ2 test. In addition, for the primary outcome, we performed a segmented regression analysis to account for the possibility of concurrent secular trends in violence that could influence the results. We evaluated the effect of the programme on violence at both the aggregate and individual patient levels.

First, a segmented Poisson regression model offset by the total number of admissions at OED per month was used to compare monthly violence rates between the pre-intervention and intervention periods. The model included intercept, time trend before implementation, change in level immediately after the training period and change in time trend after the training period.

Analyses were stratified to allow for differential effects by age group, gender, waiting time and length of stay. Results were reported as incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CIs.

Second, logistic regression was used to assess change in level and trend of odds of violence occurrence within admission at OED before and after each intervention after adjusting for individual characteristics (age, gender, waiting time>2 hour, admission to OED during public holidays, night admission and patients with several admissions to OED). A model with generalised equation estimation with a first-order autoregressive correlation structure was fitted to account for the clustering of admissions to the OED within a calendar day. Results were reported as OR and 95% CIs.

All admissions to the OED were treated independently. All p values were two-sided and statistical significance level was set at alpha=0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS V.9.4 software.

Reporting criteria

We followed the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) criteria from the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of health Research (EQUATOR) network to report the study.32

Results

Participants

Over the 15-month study period, 22 107 admissions (corresponding to 18 826 patients) were analysed (figure 1). Among the 18 826 patients, 12% were admitted more than once. The mean±SD number of visits per patient was 1.2±0.6 (range 1–15); there was a mean 70±12 admissions per day over the 315-day study period (range 33–105).

Characteristics of admissions

Characteristics of admissions according to the components implemented are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of admissions

| Pre-intervention period n=4118 |

Intervention period | ||||

| A n=4403 |

A+BC n=4587 |

ABC+D n=4454 |

ABCD+E n=4545 |

||

| Male, n (%) | 2250 (54.6) | 2335 (53.0) | 2499 (54.5) | 2426 (54.5) | 2564 (56.4) |

| Age≥40 years, n (%) | 2159 (52.4) | 2547 (57.8) | 2452 (53.5) | 2368 (53.2) | 2459 (54.1) |

| Coming during the day, n (%) | 2944 (71.5) | 3164 (71.9) | 3536 (77.1) | 3519 (79.0) | 3324 (73.1) |

| Waiting time>2 hours*, n (%) | 2755 (66.9) | 2754 (62.5) | 2377 (51.8) | 2100 (47.1) | 2125 (46.8) |

| Length of stay>3 hours, n (%) | 2045 (49.7) | 2481 (56.3) | 2002 (43.6) | 1601 (35.9) | 1595 (35.1) |

Coming during the day corresponded to admission between 08:00 and 19:59; Waiting time was defined as the interval between time of registration of patient’s arrival and first time of assessment by a nurse or an ophthalmologist; Length of stay was defined as the interval between registration and discharge. Components: A corresponds to computerised triage algorithm, BC corresponds to signage and message broadcast, D corresponds to mediator and E corresponds to video surveillance.

*Waiting time was not documented for 108 admissions.

Outcomes

A total of 376 acts of violence, corresponding to 272 admissions (1.4% of 22 107 admissions), were recorded during the total study period (table 3). Among the 272 admissions concerned, 74% (n=202) had led to one act of violence, 16% (n=45) had led to two acts and 10% (n=25) had led to three or more acts. In the pre-intervention period, 98.6% of acts of violence were incivilities or verbal harassments and 1.4% were threats. In the intervention period, all acts of violence were incivilities or verbal harassments.

Table 3.

Characteristics of acts of violence reported by healthcare workers

| Pre-intervention period n=4118 |

Intervention period after a 3-month training | ||||

| A n=4403 |

A+BC n=4587 |

ABC+D n=4454 |

ABCD+E n=4545 |

||

| Rate of acts of violence per 1000 admissions (95% CI)* | 24.8 (20.0 to 29.5) | 10.0 (7.1 to 12.9) | 8.9 (6.2 to 11.7) | 8.1 (5.5 to 10.7) | 10.8 (7.8 to 13.8) |

| Act of violence†, n | 143 | 54 | 51 | 56 | 72 |

| Level of violence, n (%) | |||||

| Level 1 (incivility) | 131 (91.6) | 46 (85.2) | 45 (88.2) | 43 (76.8) | 65 (90.3) |

| Level 2 (verbal harassment) | 10 (7.0) | 7 (13.0) | 5 (9.8) | 13 (23.2) | 7 (9.7) |

| Level 3 (threat) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Level 4 (assault) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Committed by patient, n (%) | 98 (68.5) | 43 (79.6) | 35 (68.6) | 38 (67.9) | 53 (73.6) |

| Healthcare worker as the victim*, n (%) | 140 (97.9) | 51 (94.4) | 48 (94.1) | 54 (96.4) | 72 (100) |

Components: A corresponds to computerised triage algorithm, BC corresponds to signage and message broadcast, D corresponded to mediator and E corresponds to video surveillance.

*Rate of acts of violence was defined as the percentage of admissions per period with at least one act of violence reported.

†Several acts of violence could occur per admission.

‡Six acts of violence were committed between patients, and the victim was not documented for five acts of violence.

Primary outcome

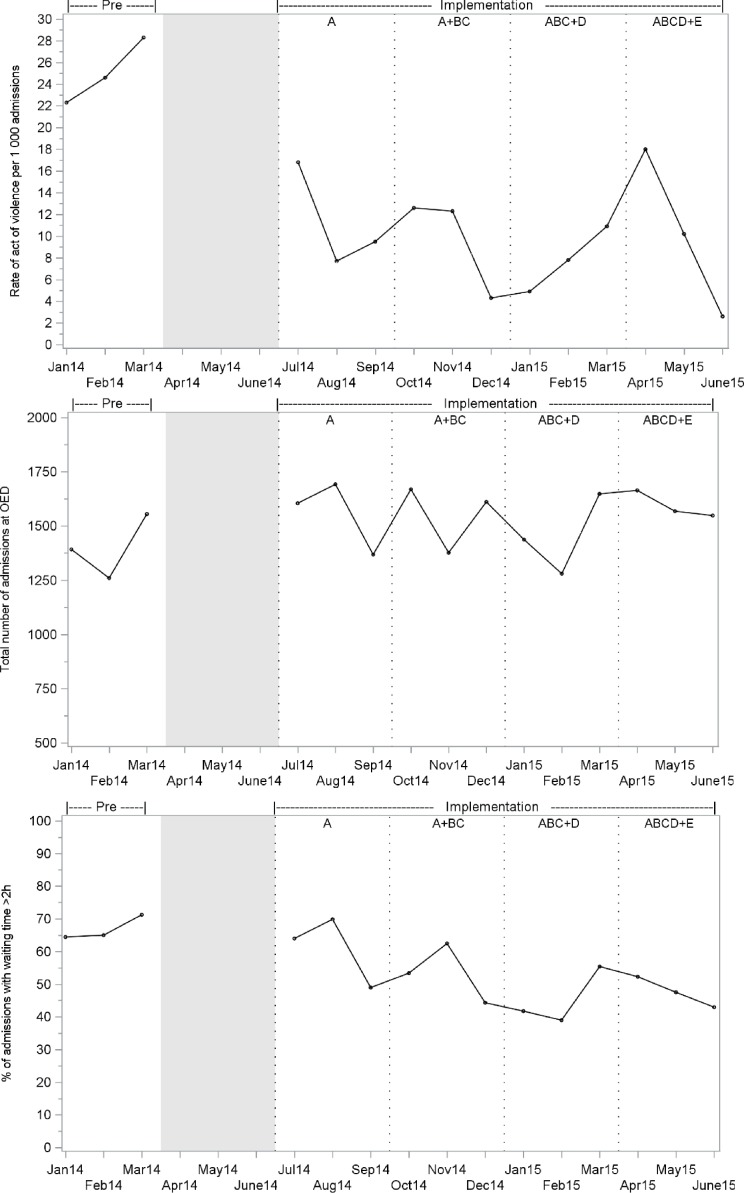

The rate of violence significantly decreased from 24.8 (95% CI 20.0 to 29.5) acts of violence per 1000 admissions in the pre-intervention period to 9.5 (95% CI 8.0 to 10.9) acts of violence per 1000 admissions in the intervention period (p<0.001). The effects of the components on monthly violence rates are shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Observed time series of the (A) rates of admission at OED with acts of violence, (B) total number of admissions at OED and (C) rates of admissions with waiting time greater than 2 hours, by month before and during implementation of the prevention programme. The grey band represents the 3-month training period. The dotted lines inside the scatter plots represents the implementation of component A (computerised triage algorithm), component BC (signage and messages broadcast on TV in the waiting rooms), component D (mediator) and component E (video surveillance). OED, ophthalmology emergency department.

Secondary outcomes

The frequency of admissions with waiting times≥2 hours decreased from 67% (n=2755 admissions) to 52% (n=9356) between the pre-intervention and intervention periods (p<0.001). For the length of stay, frequency of admissions with a stay≥3 hours decreased from 50% (n=2045) to 43% (n=7679; p<0.001).

Segmented regression analysis

According to the Poisson regression analyses, no pre-intervention trend was found in monthly violence rates (IRR=1.13, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.46, p=0.3243). After accounting for underlying trends, an immediate 53% decrease (IRR=0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.82, p=0.0121) was observed in the violence rate of the first month following the training period. No monthly trend effects in overall intervention period was detected (IRR=0.97, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.02, p=0.1660). Poisson regression results stratified by admission’s characteristics are presented in table 4. Following the training period, a similar immediate decrease was found for female (IRR=0.35, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.83, p=0.0212), age<40 years (IRR=0.43, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.99, p=0.0471), waiting time>2 hours (IRR=0.49, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.92, p=0.0306) and length of stay>3 hours (IRR=0.38, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.74, p=0.0089). No monthly trend effect in the intervention period was observed for all subgroups.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis* of the comprehensive prevention programme on violence rates by admissions characteristics

| Characteristics | Pre-intervention trend (per month)† |

Change in level‡ | Change in trend (per month)§ |

|||

| IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | IRR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.46) | 0.7500 | 0.59 (0.28 to 1.20) | 0.1308 | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.01) | 0.0810 |

| Female | 1.27 (0.84 to 1.93) | 0.2343 | 0.35 (0.15 to 0.83) | 0.0212 | 1.00 (0.93 to 1.07) | 0.9548 |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <40 | 1.11 (0.78 to 1.58) | 0.5292 | 0.43 (0.19 to 0.99) | 0.0471 | 0.96 (0.90 to 1.04) | 0.2771 |

| ≥40 | 1.16 (0.79 to 1.69) | 0.4107 | 0.51 (0.24 to 1.08) | 0.0730 | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.04) | 0.3601 |

| Waiting time (hours) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 1.11 (0.67 to 1.85) | 0.6468 | 0.39 (0.13 to 1.18) | 0.0892 | 0.96 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.3427 |

| >2 | 1.12 (0.83 to 1.51) | 0.4233 | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.92) | 0.0306 | 0.99 (0.94 to 1.04) | 0.6704 |

| Length of stay (hours) | ||||||

| ≤3 | 1.03 (0.66 to 1.62) | 0.8738 | 0.57 (0.22 to 1.51) | 0.2329 | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 0.2823 |

| >3 | 1.13 (0.82 to 1.55) | 0.4231 | 0.38 (0.20 to 0.74) | 0.0089 | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.06) | 0.9764 |

*Segmented Poisson regression offset by the total number of admissions at OED per month. RR<1 represents a decline and conversely, RR>1 represents an increase in monthly violence rate.

†Rate of change in monthly violence rate prior to the intervention (ie, time effect).

‡Immediate change in the mean monthly violence rate from pre-intervention to intervention period.

§Change in slope per month following the intervention period.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; OED, ophthalmology emergency department.

Piecewise logistic regression analysis

Piecewise logistic regression analysis confirmed the absence of pre-intervention trend (see table 5). Following the training period, three components of the programme had significant effects on the underlying trend of violence occurrence. There was a significant decline in the odds of violence occurrence over time after the implementation of component A—algorithm (adjusted OR (aOR)=0.87, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.91, p<0.001). The trend towards decreasing occurrence of violence over time significantly reversed in the 3 months following the implementation of component D—mediators (aOR=1.45, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.84, p=0.002), indicating a significant increase over time after the implementation of a mediator. The trend significantly reversed following component E—video surveillance (aOR=0.65, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.93, p=0.019), suggesting that the magnitude of increase in the occurrence of violence decreased over time and returned at its previous level (aOR=0.84, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.07, p=0.152). No effect was observed for the component BC—combining signage and messages broadcast on TV in the waiting rooms.

Table 5.

Piecewise logistic regression analysis of the comprehensive prevention programme effects* on violence

| Full model† | Simple model‡ | |||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Trend prior to intervention (per month) | 1.09 (0.81 to 1.49) | 0.5848 | – | – |

| Immediate change in level | ||||

| A | 0.31 (0.03 to 3.20) | 0.3236 | – | – |

| BC added to A | 2.19 (0.70 to 6.82) | 0.1773 | – | – |

| D added to ABC | 1.05 (0.28 to 3.88) | 0.9406 | – | – |

| E added to ABCD | 5.73 (2.08 to 15.77) | 0.0007 | – | – |

| Change in trend (per month) | ||||

| A | 0.95 (0.55 to 1.65) | 0.8657 | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.92) | <0.0001 |

| BC added to A | 0.61 (0.33 to 1.13) | 0.1188 | – | – |

| D added to ABC | 1.85 (0.98 to 3.48) | 0.0572 | 1.45 (1.14 to 1.84) | 0.0022 |

| E added to ABCD | 0.35 (0.17 to 0.70) | 0.0031 | 0.65 (0.45 to 0.93) | 0.0194 |

Components: A corresponds to computerised triage algorithm, BC corresponds to signage and messages broadcast on TV in the waiting rooms, D corresponds to mediator and E corresponds to video surveillance.

*Logistic generalised estimating equation model adjusted for waiting time>2 hours. OR<1 represent a decline and inversely, OR>1 represent an increase in monthly likelihood of violence occurrence during admission at OED per month.

†Full model included time effect and immediate changes after each component’s implementation and changes in slopes.

‡Parsimonious model after backward selection.

OED, ophthalmology emergency department.

Discussion

The present study found a significant reduction in self-reported incivility or verbal violence by healthcare workers following the implementation of a comprehensive prevention programme. This reduction occurred after the implementation of the first component of the programme, a triage algorithm, and was maintained over time while other components were successively implemented.

The violence rate during the pre-intervention period found in the present study (24.8 per 1000 admissions) was higher than that previously reported. In a recent meta-analysis of 22 studies, the authors found a pooled incidence of 36 per 10 000 admissions (range 1–172 per 10 000 admissions).33 It is, however, difficult to compare our result with those reported elsewhere due to heterogeneity in the way violence is defined, collected and reported in the literature; for a majority of studies, data collection was conducted retrospectively, using security records and incident report documents that mainly report severe acts of violence.33

Previous studies reported a low rate of acts of violence with a high level of severity (threats and assaults).33 34 In the present study, the frequency of such acts were even lower; only four acts of verbal or physical threat and no assault. This can be explained by the context of the OED that did not admit patients for drug/alcohol abuse or psychiatric disease which are predictors of physical violence perpetrated by patients against healthcare workers.35 As in other studies, verbal harassment or incivility committed by patients were the most frequent form of violence experienced herein despite differences in methodology.36–38 Waiting times and length of stay of patients in the OED were significantly reduced. The reduction of waiting times was an expected effect of the triage algorithm, which allowed, according to the reason for consultation, for orthoptists to perform examinations, such as dilating pupils, without having to consult a physician. Associated with a patient call system in the waiting room, the triage algorithm was a mean to rationalise the order of passage and waiting time, and thus reduce the stressful condition in waiting rooms.35 The reduction of waiting times was not related to a change in the number of professionals (which remained stable throughout the study) nor to a change in the number of admissions to OED.

As recommended, the prevention programme combined different components, targeting regularly cited causes of violence.24 The intervention targeted patients/visitors and the environment, but did not target how OED professionals handle violent situations.38–40 Behaviour of healthcare professionals, such as empathic communication, early proactive interaction, and verbal and body language expressing respect and confidence, is associated with a reduction in incivility and verbal abuse or aggressive behaviour.28 35 41

Caution should, however, be taken when interpreting the results of the present study. It is not possible to distinguish the relative effect of the tested components. For instance, a positive effect was observed during the implementation of the first component (triage algorithm linked to a waiting room patient call system). It is not possible to conclude whether this effect was due to the algorithm or to the fact that it was implemented first. Another point to consider is that violence increased despite the presence of the mediator. To the best of our knowledge, there was no change in the conditions of patient reception (ie, no increase in waiting times or admission frequency and no change in the OED team) during the implementation of the mediator that could explain this unintended effect. The mediator, by his/her presence, may have stimulated the declaration of violence by healthcare workers. It highlights the difficulty to collect non-physical acts of violence that are underreported by healthcare staff. The main reasons for this are that it is prevalent yet rarely results in physical injury, most professionals consider it as part of their jobs, these acts of violence are subject to personal interpretation, and the use of existing reporting systems is time-consuming and perceived as unnecessary because it does not lead to any action to reduce such behaviour.24 28 41–43 To limit variation in reporting practices, the researchers met monthly with the OED team to discuss the importance of reporting events from the least (incivility) to most severe (assault). Moreover, reporting was facilitated by its integration in the patient records.

We conducted a segmented regression analysis to detect if the programme had a greater effect than an underlying secular trend.30 31 44–46 The analysis was limited by the short pre-intervention period, which did not allow a solid estimation of the trend before the programme implementation.

Second, a longer post-intervention follow-up could have been useful to verify the effectiveness of the programme at a distance of time from its implementation.47 A longer observation period could have helped to explain whether the increase in the reports after the implementation of the mediator was a real phenomenon (increase of the violence) or not (greater attention to violence). A qualitative approach would have also helped us to better understand the mechanisms of action of the programme components,48 in particular, the paradoxical effect of the mediator. It would have allowed us to evaluate whether the coping of the healthcare workers with the violence has improved. Finally, the generalisation of the results is limited by the single-centre study design and the differences between the OEDs and general emergencies. In particular, there are no admissions for psychiatric or drug abuse and alcohol problems, which are known to be sources of violence.33 35

In conclusion, a comprehensive prevention programme targeting patients, visitors and environment can reduce self-reported incivility and verbal violence by healthcare workers in an OED over 12 months. EDs should develop a comprehensive primary prevention programme that integrates various environmental and patient-oriented components (organisational, educational, relational and security).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the OED team. We also acknowledge the hard work and the active support of Sylvie Sullerot, advance practice nurse of the OED, Daniel Betito, computer scientist, for the implementation of the algorithm in the hospital information system, Hélène Janin-Magnificat, physician, for her support of the study and the students of the communication school of Lyon for the creation of the messages broadcast on TV in the waiting rooms.

The authors are grateful to Philip Robinson for help in manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was conceptualised and designed by ST, P-LC, M-ALP and ADu. P-LC and CB are the co-chief investigators, provided leadership for the project. ST, P-LC, J-BF and ADu contributed to the development of the programme. ST, PO and ADe planned the statistical analysis. ADe carried out statistical analyses. ST, PO and ADe drafted the manuscript. All the authors reviewed the draft version, made suggestions and approved the final version.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Programme de Recherche en Qualité Hospitalière 2011 (PRQH 2011—D50794) of the French Ministry of Health (Ministère chargé de la Santé, Direction de l’Hospitalisation et de l’Organisation des Soins). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Sud-Est IV Institutional Review Board’s approval was obtained in September 2011 (L11-117).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1. Bureau of Labor Statistics News release: nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work. United state department of labor (USDL 15-2205). Available: http://www.bls. gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf [Accessed 26 May 2018].

- 2. Kuehn BM. Violence in health care settings on rise. JAMA 2010;304:511–2. 10.1001/jama.2010.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Magnavita N, Heponiemi T. Violence towards health care workers in a public health care facility in Italy: a repeated cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:108 10.1186/1472-6963-12-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnetz JE, Aranyos D, Ager J, et al. Development and application of a population-based system for workplace violence surveillance in hospitals. Am J Ind Med 2011;54:925–34. 10.1002/ajim.20984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lau JBC, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the emergency department: a literature review. Australas Emerg Nurs J 2004;7:27–37. 10.1016/S1328-2743(05)80028-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gates DM, Ross CS, McQueen L. Violence against emergency department workers. J Emerg Med 2006;31:331–7. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kowalenko T, Cunningham R, Sachs CJ, et al. Workplace violence in emergency medicine: current knowledge and future directions. J Emerg Med 2012;43:523–31. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Winstanley S, Whittington R. Aggression towards health care staff in a UK General Hospital: variation among professions and departments. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:3–10. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ryan D, Maguire J. Aggression and violence - a problem in Irish Accident and Emergency departments? J Nurs Manag 2006;14:106–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00571.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Crilly J, Chaboyer W, Creedy D. Violence towards emergency department nurses by patients. Accid Emerg Nurs 2004;12:67–73. 10.1016/j.aaen.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Behnam M, Tillotson RD, Davis SM, et al. Violence in the emergency department: a national survey of emergency medicine residents and attending physicians. J Emerg Med 2011;40:565–79. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Underreporting of workplace violence: comparison of self-report and actual documentation of hospital incidents. Workplace Health Saf 2015;63:200–10. 10.1177/2165079915574684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ramacciati N, Gili A, Mezzetti A, et al. Violence towards emergency nurses: the 2016 Italian national Survey-A cross-sectional study. J Nurs Manag 2019;27:792–805. 10.1111/jonm.12733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Observatoire National des Violences en milieu de Santé La prévention des atteintes aux personnes et aux biens en milieu de santé. Guide méthodologique. Ed. Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins, 2017. Available: http://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/guide_onvs_-_prevention_atteintes_aux_personnes_et_aux_biens_2017-04-27.pdf [Accessed 26 May 2018].

- 15. Lyneham J. Violence in New South Wales emergency departments. Aust J Adv Nurs 2000;18:8–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJG, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2005;49:283–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. The Lancet 2009;374:1714–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gates DM, Gillespie GL, Succop P. Violence against nurses and its impact on stress and productivity. Nurs Econ 2011;29:59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Magnavita N. Workplace violence and occupational stress in healthcare workers: a chicken-and-egg situation-results of a 6-year follow-up study. J Nurs Scholarsh 2014;46:366–76. 10.1111/jnu.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khangura JK, Flodgren G, Perera R, et al. Primary care professionals providing non-urgent care in hospital emergency departments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11 10.1002/14651858.CD002097.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garnham P. Understanding and dealing with anger, aggression and violence. Nurs Stand 2001;16:37–42. 10.7748/ns2001.10.16.6.37.c3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hodge AN, Marshall AP. Violence and aggression in the emergency department: a critical care perspective. Aust Crit Care 2007;20:61–7. 10.1016/j.aucc.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gates D, Gillespie G, Smith C, et al. Using action research to plan a violence prevention program for emergency departments. J Emerg Nurs 2011;37:32–9. 10.1016/j.jen.2009.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B, et al. Interventions to reduce the risk of violence toward emergency department staff: current approaches. Open Access Emerg Med 2016;8:17–27. 10.2147/OAEM.S69976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soremekun OA, Capp R, Biddinger PD, et al. Impact of physician screening in the emergency department on patient flow. J Emerg Med 2012;43:509–15. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morphet J, Griffiths D, Plummer V, et al. At the crossroads of violence and aggression in the emergency department: perspectives of Australian emergency nurses. Aust. Health Review 2014;38:194–201. 10.1071/AH13189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weiland TJ, Ivory S, Hutton J. Managing acute behavioural disturbances in the emergency department using the environment, policies and practices: a systematic review. West J Emerg Med 2017;18:647–61. 10.5811/westjem.2017.4.33411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. d'Aubarede C, Sarnin P, Cornut P-L, et al. Impacts of users' antisocial behaviors in an ophthalmologic emergency department--a qualitative study. J Occup Health 2016;58:96–106. 10.1539/joh.15-0184-FS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Touzet S, Cornut P-L, Fassier J-B, et al. Impact of a program to prevent incivility towards and assault of healthcare staff in an ophtalmological emergency unit: study protocol for the PREVURGO on/off trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:221 10.1186/1472-6963-14-221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299–309. 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:348–55. 10.1093/ije/dyw098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, et al. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf 2016;25:986–92. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nikathil S, Olaussen A, Gocentas RA, et al. Review article: workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta analysis. Emerg Med Australas 2017;29:265–75. 10.1111/1742-6723.12761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maguire BJ, O'Meara P, O'Neill BJ, et al. Violence against emergency medical services personnel: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Ind Med 2018;61:167–80. 10.1002/ajim.22797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. D'Ettorre G, Pellicani V, Mazzotta M, et al. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in emergency departments. Acta Biomed 2018;89:28–36. 10.23750/abm.v89i4-S.7113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tadros A, Kiefer C. Violence in the emergency department: a global problem. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2017;40:575–84. 10.1016/j.psc.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kowalenko T, Gates D, Gillespie GL, et al. Prospective study of violence against ED workers. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:197–205. 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Kowalenko T, et al. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:586–91. 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernandes CMB, Raboud JM, Christenson JM, et al. The effect of an education program on violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:47–55. 10.1067/mem.2002.121202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gillespie GL, Farra SL, Gates DM. A workplace violence educational program: a repeated measures study. Nurse Educ Pract 2014;14:468–72. 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ramacciati N, Ceccagnoli A, Addey B, et al. Violence towards emergency nurses: a narrative review of theories and frameworks. Int Emerg Nurs 2018;39:2–12. 10.1016/j.ienj.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Copeland D, Henry M. Workplace violence and perceptions of safety among emergency department staff members: experiences, expectations, tolerance, reporting, and recommendations. J Trauma Nurs 2017;24:65–77. 10.1097/JTN.0000000000000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pich J, Hazelton M, Sundin D, et al. Patient-Related violence against emergency department nurses. Nurs Health Sci 2010;12:268–74. 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, et al. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:613–23. 10.1017/S0266462303000576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lagarde M. How to do (or not to do). Assessing the impact of a policy change with routine longitudinal data. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:76–83. 10.1093/heapol/czr004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr 2013;13(6 Suppl):S38–S44. 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Magnavita N. Violence prevention in a small-scale psychiatric unit: program planning and evaluation. Int J Occup Environ Health 2011;17:336–44. 10.1179/oeh.2011.17.4.336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Guével M-R, Pommier J. [Mixed methods research in public health: issues and illustration]. Sante Publique 2012;24:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.