Abstract

Introduction

Fractures of the tibial plateau are in constant progression. They affect an elderly population suffering from a number of comorbidities, but also a young population increasingly practicing high-risk sports. The conventional open surgical technique used for tibial plateau fractures has several pitfalls: bone and skin devascularisation, increased risks of infection and functional rehabilitation difficulties. Since 2011, Poitiers University Hospital is offering to its patients a new minimally invasive technique for the reduction and stabilisation of tibial plateau fractures, named ‘tibial tuberoplasty’. This technique involves expansion of the tibial plateau through inflation using a kyphoplasty balloon, filling of the fracture cavity with cement and percutaneous screw fixation. We designed a study to evaluate the quality of fracture reduction offered by percutaneous tuberoplasty versus conventional open surgery for tibial plateau fracture and its impact on clinical outcome.

Methods and analysis

This is a multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing two surgical techniques in the treatment of tibial plateau fractures. 140 patients with a Schatzker II or III tibial plateau fracture will be recruited in France. They will be randomised either in tibial tuberoplasty arm or in conventional surgery arm. The primary outcome is the postoperative radiological step-off reduction blindly measured on CT scan (within 48 hours post-op). Additional outcomes include other radiological endpoints, pain, functional abilities, quality of life assessment and health-economic endpoints. Outcomes assessment will be performed at baseline (before surgery), at day 0 (surgery), at 2, 21, 45 days, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months postsurgery.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the ethics committee Ile-De-France X and will be conducted in accordance with current Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines, Declaration of Helsinki and standard operating procedures. The results will be disseminated through presentation at scientific conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrial.gov:NCT03444779.

Keywords: tibial plateau fracture, balloon reduction, minimally invasive surgery, randomised controlled trial

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a multicentre, randomised, controlled trial with a calculated number of subjects required to have 80% power to detect a 25% difference in postoperative radiological step-off reduction of tibial plateau fracture by tibial tuberoplasty versus conventional surgery.

Primary endpoint blindly evaluated on CT scan by an independent imaging core lab will provide robust and reliable data.

Learning curve for tibial tuberoplasty technique could create a bias for endpoint evaluation. For this purpose, each surgeon will participate in a tibial tuberoplasty workshop before the study.

Unblinded patient’s follow-up could introduce a bias for secondary endpoints evaluation.

Introduction

French Medico-Administrative database (from Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d'Information) show >10 000 proximal tibial fractures diagnosed in 2014 and 4055 lateral tibial plateau fractures operated in 2013 in France.1 Half (50%) of these fractures are related to the lateral condyle and cause split/depression (Schatzker II) or pure depression (Schatzker III).2 This high rate results from the recent democratisation of high-risk sports,3 as well as an ageing population with increased risks of falling.4 Aside from the resulting reduced physical activity, the social and professional impact of these fractures is undeniable and represents significant costs for the healthcare system. A recently published prospective case series reports 28 job losses out of 41 patients treated.5

The clinical outcome of these patients depends mainly on the primary stability provided by the surgical treatment, after the greatest anatomical reduction possible. Indeed, Giannoudis et al have demonstrated that under simple X-rays, the smaller the detected step-off, the better the outcome.6 The aim is to allow for recovery of good joint mobility to promote rapid resumption of activity and to limit the onset of early osteoarthritis.7

The conventional open surgical technique using a bone tamp for reduction and osteosynthesis of tibial plateau fractures has several pitfalls3: devascularisation of the bone and skin, increased risks of infection and functional rehabilitation difficulties with delayed recovery of weight-bearing. Moreover, this technique does not allow for the simultaneous diagnosis and treatment of other possible lesions, such as meniscal injuries in particular.

Since 2011, Poitiers University Hospital is offering to its patients a new minimally invasive technique for the reduction and stabilisation of tibial plateau fractures, baptised ‘tibial tuberoplasty’.8

The concept derives from the divergent use of vertebral kyphoplasty, initially dedicated to spinal injuries and transposed here to the tibial plateau. This technique involves expansion of the tibial plateau through inflation of a kyphoplasty balloon, filling of the created cavity with cement (PolyMethylMethAcrylate (PMMA) or calcium phosphate) and percutaneous screw fixation. A review of literature regarding this technique is summarised in table 1. The clinical outcome of these patients depends mainly on the primary stability provided by the surgical treatment, after the greatest anatomical reduction possible ‘step-off’ <5 mm, without axis shifting <5°.

Table 1.

Tuberoplasty/tibioplasty literature review

| Details | Conclusion | |

| Pizanis et al, 201224 |

Technique description + clinical and radiological results in five cases, Schatzker II/III | This new technique may be a useful tool to facilitate the reduction of select depressed tibial fractures in the future |

| Vendeuvre et al, 2013 8 | Description of tibial tuberoplasty with an anterior entry point | This new minimally invasive tuberoplasty technique is a good alternative to the conventional technique using a bone tamp in the treatment of tibial plateau fractures |

| Panzica et al, 201425 |

Cadaveric and biomechanical study, 30 test series in synthetic bones | The depth was the decisive factor in the reduction of the fracture and not the diameter |

| Craiovan et al, 201426 |

Video article describing surgical technique | Results are promising, but long-term results are still lacking |

| Ziogas et al, 201527 |

Case Report, Schatzker III, minimal approach which included percutaneous reduction of the fracture under arthroscopy and fluoroscopy guidance + CPC | Arthroscopy-assisted balloon osteoplasty seems to be a safe and effective method for the treatment of depressed tibia plateau fractures |

| Mayr et al, 201528 |

Cadeveric study, 8 matched pairs of human tibia, Schatzker III, reduction performed using a balloon inflation system, followed by cement augmentation | Loss of reduction can be minimised by using locking plate fixation after balloon reduction and cement augmentation |

| Ollivier et al, 201629 |

Prospective study, 20 patients, Schatzker II/III, tuberoplasty (optimal entry point) + CPC | The use of balloon-guided inflation tibioplasty with injection of a resorbable bone substitute is safe, and results in a high rate of anatomic reduction and good clinical outcomes |

| Doria et al, 201730 |

Randomised controlled trial, 30 patients, Schatzker II/III, tibioplasty versus traditional reduction technique | Tibioplasty technique provides anatomical reduction of the fracture in a gentle and progressive manner and mechanical stability allowing early rehabilitation and more fast weight-bearing |

| Wang et al, 201831 |

Randomised controlled trial, 80 patients, Schatzker II / III and IV, arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty versus open reduction internal fixation | Study protocol, results expected in 2021 |

| Vendeuvre et al, 201832 |

Cadaveric and biomechanical study, 12 human tibia, contribution of minimally invasive bone augmentation to primary stabilisation of the osteosynthesis of Schatzker type II tibial plateau fractures: balloon versus bone tamp | The minimally invasive balloon technique has fewer negative effects than the use of bone tamp on the osseous stock, thereby enabling better primary structural strength of the fracture |

We performed the first tibial tuberoplasties through a feasibility study on 36 cadaveric subjects and then transposed the technique to human. We identified major advantages such as minimal skin damage, possible treatment of posterior and multifragmented compressions (lifting in a single block by the balloon), reinforcement of the stability of the assembly using cement, possible use of combined arthroscopy9 (for concomitant meniscal injuries treatment10).

This technique allows for optimisation of the fracture reduction by elevating the posterior fragments with the inflatable bone tamp through an anterior approach. The reduction is made possible thanks to the specificity of the inflatable bone tamp which inflates and reduces the area of least resistance.

The aim of this innovative technique is focused on the anatomical reduction in order to restore the convexity of the tibial plateau11 which is similar to the balloon convexity.

The results from the first 40 patients operated since 2011 are promising and show a proportion of 70% presenting <5 mm step-off reduction.

There is now a need for a larger-scaled multicentre randomised controlled trial to compare the efficacy of tibial tuberoplasty versus the gold standard treatment (conventional open surgery), not only in terms of radiological step-off reduction but also in terms of functional impact.

To bridge this gap, we designed a study to evaluate the quality of fracture reduction offered by percutaneous tuberoplasty versus conventional open surgery for tibial plateau fracture and its impact on clinical outcomes.

Method and analysis

Study population

The study population comprises two target populations with tibial plateau fracture:

Young subjects with fractures mainly resulting from highway accidents and high-risk sports.

Elderly population with fractures mainly caused by falls, in the context of osteoporosis.

A patient must meet all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria to be eligible for the study.

Inclusion criteria

The subjects are >18 years old; present a Schatzker type II or III tibial plateau fracture (compression with or without split) demonstrated on CT scan and located in the lateral or medial condyle of tibia; have 10-day-old maximum fractures caused by trauma; understand and accept the constraints of the study; are beneficiaries or affiliated members of a health insurance plan; give written consent for the study after having received clear information.

Exclusion criteria

The subjects present fractures resulting from osteolysis; have open fractures; have fractures >10 days old; have concomitant fracture(s) or condition(s) during the trauma reducing the range of motion; were unable to walk before the injury; have a history of sepsis in the injured knee; have contraindications to anaesthesia, contrast agent, medical devices or cement; have a history of hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media, bone filler or metal; present a degenerative joint disease (polyarthritis and so on); require closer protection, that is, minors, pregnant women, nursing mothers, subjects deprived of their freedom by a court or administrative decision, subjects admitted to a health or social welfare establishment, major subjects under legal protection and finally patients in an emergency setting.

Sample size calculation and power calculations

The binary primary outcome is defined from the residual step-off measurement on non-contrast CT scan with a 5 mm cut-off criterion given by the literature. The results observed following treatment of this type of fracture by tibial tuberoplasty in the pilot study conducted at the Poitiers University Hospital describe a proportion of 70% presenting <5 mm step-off. A minimum of 25% difference between tuberoplasty and control (70% vs 45%) is expected. With 80% power and two-sided 5% alpha risk, the estimated number of patients is 68 per group. The total is rounded to 140 divided into two groups of 70 patients. The intended number of patients will be <50% of the total amount of tibial plateau fracture for each centre.

Study design

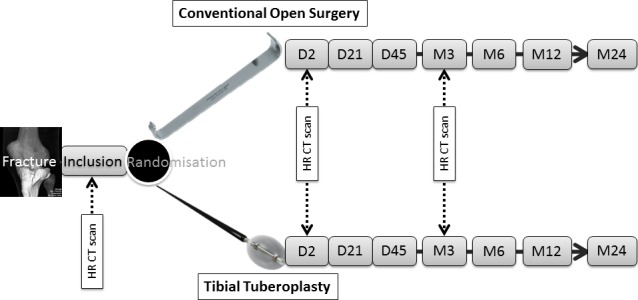

This is a blinded prospective multicentre randomised controlled trial comparing two surgical techniques in the treatment of tibial plateau fractures. Patients will be randomised 1:1 to ‘tibial tuberosplasty’ technique or conventional technique and followed-up for 24 months’ postsurgery. The enrolment period is planned to run for 12 months. The trial will be conducted at ~12 investigator sites in France. The study design is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study design.

Interventions

Control group

The patients will be treated with a conventional surgery. The reduction will be performed using a spatula, a bone tamp or open reduction internal fixation. The osteosynthesis and filling of the cavity will be performed by the same surgical access.

The conventional open surgery for reduction and fixation of tibial plateau fractures is described in the Campbell’s operative orthopaedics textbook.12 Any techniques derived from it with a minimised invasive approach and commonly used by investigator surgeons are considered as ‘conventional open surgery’.

Experimental group

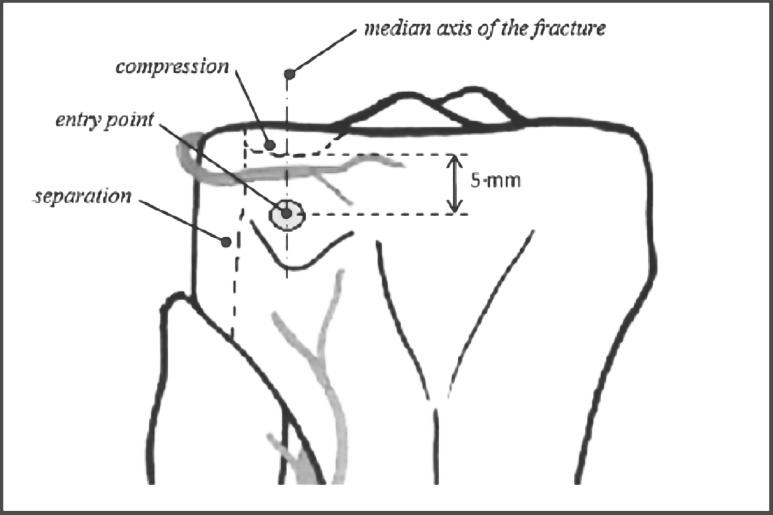

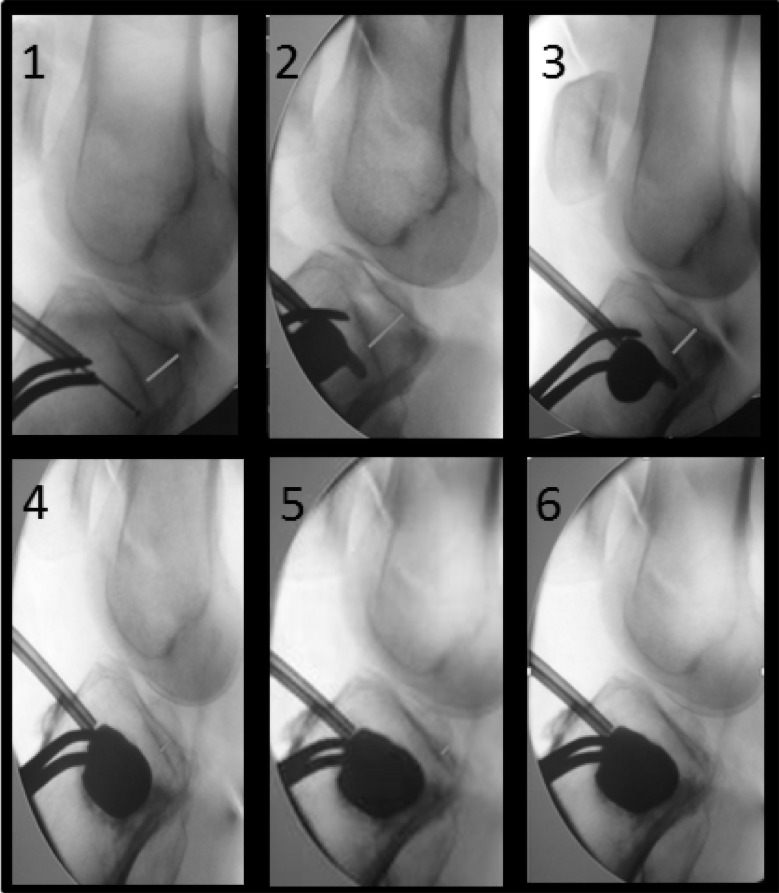

The patients will be treated with the tibial tuberoplasty technique8 under fluoroscopic guidance with or without arthroscopy. The reduction will be performed by an anterior approach using a kyphoplasty balloon (figures 2 and 3).13 The combined osteosynthesis including cannulated screws and cementoplasty will both be performed by a percutaneous technique.

Figure 2.

Tuberoplasty entry point (adapted from Hannouche et al 13).

Figure 3.

Fluoroscopy of tibial plateau fracture reduction by tuberoplasty (from Vendeuvre et al 8).

In both groups

Osteosynthesis is at surgeon’s discretion14 (screws, plates, locking plates).15 The same applies to cavity filling (vacuity, demineralised bone matrix, PMMA, calcium phosphate cement and so on).16 17 Arthroscopy is allowed.

Study objectives

The primary objective is to compare step-off anatomical reduction of tibial plateau fracture by tibial tuberoplasty versus conventional open surgery using CT scan.

Secondary objectives are to analyse and compare in both groups the clinical parameters as the knee range of motion and time to resume partial/full weight-bearing; to compare the two groups in terms of pain reduction, functional impact and quality of life; to describe the pain management and the safety of the two surgical techniques; to analyse and compare in both groups the radiological parameters to evaluate the fracture healing, the absence of axis shifting (source of secondary osteoarthritis) and the maintenance of the step-off reduction on the long-term follow-up; to compare simulated reduction (ANSYS Software) versus reduction observed on the CT scan; to assess and compare the economic impact of the two surgical techniques; to analyse the preoperative and peroperative factors which could influence the outcomes of the tuberoplasty.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint is the postoperative radiological step-off reduction blindly measured by CT scan (within 48 hours post-op) and assessed by an independent imaging core lab. The primary endpoint is defined as the proportion of patients showing an optimal reduction with <5 mm step-off. A software specially developed for medical image processing and segmentation will be used in this study to quantify the reduction in the most reliable and objective manner. The measurement error is unfortunately well known as a bias in all radiological studies. According to Kim et al,18 spacial resolution described thanks to 3D Multi-Planar Resolution mode is 0.3 mm. In order to optimise this measurement, it is important to consider scanner calibration using a phantom, 3D reconstruction in order to be in the strict plan of tibial plateau and CT scan assessment thanks to a consensus between two specialised radiologists.

Clinical secondary endpoints are knee range of motion (degrees); Numeric Pain Rating Scale; Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score questionnaire; score on Euro Quality of Life-5 Dimension Health questionnaire; time to partial and full weight-bearing (in days); pain medication changes, non-drug pain treatment, adjuvant therapies; adverse events; factors which could influence the outcomes of the tuberoplasty (age, gender, nature of the trauma, work-related injury, initial step-off, balloon technique, maximal volume inflate in the balloon, filling-in nature and volume, osteosynthesis coupled, surgery duration, arthroscopy coupled).

Radiological secondary endpoints are tibial fracture healing CT criteria as defined by Mustonen et al 19 (ie, lack of non-union signs, cortical continuity, cancellous bone replacement); residual step-off (in mm), measured on the CT scan at the level of the knee joint at M3; simulated residual step-off (ANSYS Software); femoro-tibial axes on hip–knee–ankle X-rays (in degrees).

Health-economic secondary endpoints are healthcare utilisation; employment status; incremental cost–utility ratio estimated from the perspective of the healthcare system, at 2 years, by comparing the difference in costs and quality-adjusted-life-years (QALYs) between tibial tuberoplasty and conventional open surgery for tibial plateau fractures.

Experimental design

The patients will be invited to participate in the study during a trauma care consultation. Once the informed consent form has been signed, the inclusion criteria have been checked and a CT scan has been performed, the patients will be randomised through a central randomisation list. Each included patient will be identified with a single patient number. The patients will be treated in the surgical theatre within 10 days following the trauma, either by the minimally invasive technique or by conventional surgery. As tuberoplasty is a new surgical technique, the surgeons involved in this study will receive specific theoretical and practical training before to start the trial.

Follow-up with a non-contrast CT scan will be performed 2 days and 3 months after the surgery to analyse the maintenance of the reduction. A blinded evaluation will be performed by an independent imaging core lab.

Patients will be assessed prior the randomisation and the surgery (D0) and 2, 21, 45 days and 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after. An independent medical evaluator blinded for the surgical technique will assess the patient during the follow-up visits. Axis shifting will be checked at 3-month, 6-month, 12-month and 24-month follow-up visits by performing hip–knee–ankle films.

The 2-year follow-up visit of the patients will be used to monitor the stability of the reduction over time, to check the safety of this new technique and to evaluate the occurrence of secondary early osteoarthritis.

The study flowchart is summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Study flowchart

| Inclusion visit |

Surgery D0 |

D2

visit |

D21

visit |

D45

visit |

M3

visit |

M6

visit |

M12

visit |

M24

visit |

|

| Patient information | X | ||||||||

| Informed consent form | X | ||||||||

| Demographics (ie, age, gender) | X | ||||||||

| Medical history | X | ||||||||

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | X | ||||||||

| Randomisation | X | ||||||||

| Fracture reduction | X | ||||||||

| CT scan | X | X | X | ||||||

| Operative report | X | ||||||||

| Knee X-ray | X | X | |||||||

| Hip–knee–ankle X-ray (axis shifting) | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Knee range of motion (degrees) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Numeric Pain Rating Scale | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| KOOS questionnaire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| EQ5D-5L | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Pain medication changes, non-drug pain treatment, adjuvant therapies | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Healthcare utilisation | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Employment status | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Adverse events | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

EQ5D-5L, EuroQol 5 Dimensions-5 Levels; KOOS, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score.

Procedures designed to minimise bias

Randomisation method

Subjects who give informed consent and fulfil the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be randomised to be operated using the tibial tuberoplasty or using the open technique in a 1:1 ratio.

The permuted-block randomisation list, stratified by centre, will be prepared by a methodologist using a random selection programme developed under SAS V.9.4. The randomisation numbers will be assigned in strict sequence, that is, when a subject is confirmed as eligible for randomisation, the next unassigned randomisation number in sequence will be given. The randomisation allocation will be concealed from the evaluators and subject, using a centralised automatic web-based data management system. Once assigned the randomisation assignment for the subject cannot be changed. Early departure from the study for any reason whatsoever, will not give rise to replacement or reassignment of the rank of inclusion.

Blindness

The surgeons who participated in the study are not allowed to become evaluators. An independent medical evaluator blinded for the surgical technique will assess the patient during the follow-up visits. The peroperative dressing applied during the intervention will be replaced by uniform dressing after the 48 hours CT scan to maintain the patient blinded. In order to keep the evaluator blinded, at every follow-up visit, the patient must wear opaque compression socks to hide the surgery scars.

For the primary endpoint assessment, a blinded CT scan evaluation will be performed by an independent imaging core lab. To dissimulate the incision side and the technique from the radiologists, the surgeon will close the incisions with radio-transparent suture and not with a skin stapler. For reminder, osteosynthesis and filling are totally at surgeon discretion, whatever the randomisation group.

Confidentiality, data collection and quality control

People with direct access to the data will take all necessary precautions to maintain confidentiality. All data collected during the study will be anonymised. Each patient will only be identified by his/her initials and inclusion number.

Clinical research assistants are available at each participating hospital to help investigators with running the study and data collection. Data will be collected through an electronic Case Report Form (eCRF).

A clinical research associate, mandated by the sponsor, will ensure that patient’s rights and safety are respected, that inclusion and data collection are in line with the protocol and that the study is conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines.

Data analysis

All analyses will be performed by a methodologist-biostatistician using the SAS statistical package V.9.4. The analysis will be performed on an intention-to-treat basis after validation by a blind review committee of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for each patient. Unblinding will be performed after the blind review.

Two types of population are expected in this study. These populations will be included in the statistical analysis as a modifying factor, as the clinical expectations, medical and economic repercussions are different. According to Rothman,20 effect modification refers to a change in magnitude of an effect measure according to the value of some third variable which is called an effect modifier.

Dealing with a suspected effect modifier requires to stratify the analysis, not necessarily to stratify the randomisation plan.

Stratified analysis will provide a pooled estimate of treatment effect (as usual) as well as stratum-specific estimates. Homogeneity between age strata will be tested from the interaction between age stratum and treatment from bivariate logistic regression.

Descriptive analysis

The continuous variables will be summarised with the classic parameters of descriptive analysis (median, IQR and extreme values or mean and SD), while indicating the number of missing data. The categorical variables will be presented in the form of numbers and percentages in each modality.

Eligibility criteria will be verified on the basis of the data recorded in the case reports. Wrongly included subjects as those lost to follow-up will be described. Deviations from the protocol will be described and analysed on a case-by-case basis.

Analysis pertaining to the primary criterion

The proportion of patients showing an optimal reduction with <5 mm residual step-off will be compared between the two groups at day 2 using Fisher’s exact test at the two-sided p<5% significance level.

The different parameters that would be potentially predictive of an optimal reduction with <5 mm step-off (which include young vs elderly population) will be investigated by means of the Student’s t-test (or the Mann-Whitney U test, if necessary) for continuous quantitative variables and by Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables.

The univariate analysis will be followed by multivariate logistic regression. The initial logistic model will include all variables associated with the dependent outcome (p<0.20) as well as relevant variables according to the literature (forced variables). The model will be simplified according to a step-by-step elimination procedure; only the variables associated with the dependent variable (threshold p value: 5%) and the forced variables will be retained in the final model. Interactions will be tested in the final model. Goodness of fit will be assessed using the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ² test.

Analysis pertaining to the secondary criteria

The secondary criteria will be compared using Mann-Whitney U test for quantitative variables and Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables.

The incremenatal cost–utility ratio is defined by the difference in average total cost divided by the average 2-year QALYs, the uncertainty of the results will be analysed using a non-parametric bootstrap which provides multiple estimates of the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) by randomly re-sampling the patient population 1000 times. The results will be presented in a scatter plot of 1000 ICERs on the cost-effectiveness plane and transformed into a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve based on the decision-makers’ willingness to pay for an additional QALY.

Timing of analysis

A first analysis on primary and second outcomes is planned after the last day 2 CT scan of the last patient included in the study. This analysis will provide data to prepare a publication. A final analysis is planned after the last patient last visit.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or public were not involved in study design, recruitment or conduct. Study results will be disseminated to study participants via a thank you letter which will received at the end of the study.

Discussion

Justification of study primary objective and primary endpoint

In the treatment of tibial plateau fracture, the complexity to transpose anatomical reduction to clinical outcome explains that surgical treatment efficacy could be assessed by three different types of criteria: (1) an initial radiological evaluation documenting the anatomical reduction (step-off reduction); (2) a clinical assessment reflecting the functional impact of the treatment (in terms of mobilisation, pain, daily activity); (3) a long-term follow-up analysing the potential articular degeneration (based on radiological and clinical parameters).

Giannoudis et al have demonstrated that under simple X-rays, the smaller the detected step off, the better the outcome.6 We therefore decided to consider and compare the radiological step-off reduction as the primary objective of this study since the quality of the fracture initial reduction appears to be the determinant factor of clinical outcome.

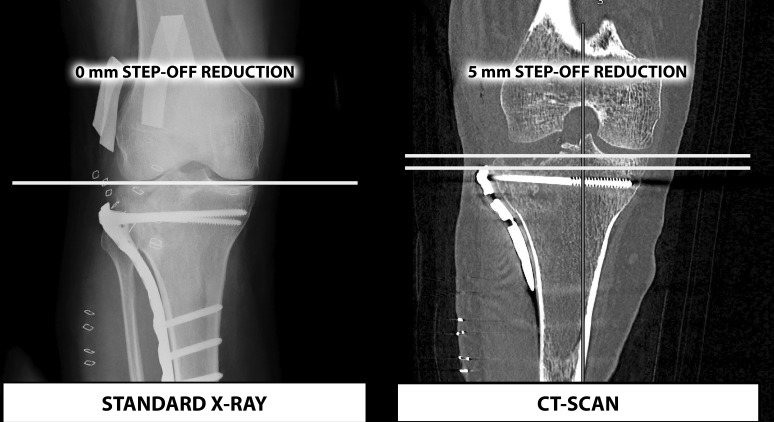

In this context, it remains surprising that, on the one hand, the preoperative use of CT scan is considered as a decisive tool to classify the tibial fracture type and to choose the treatment,21 on the other hand, the majority of surgeons use standard post-op X-ray and no CT scan to evaluate the fracture reduction.

In addition, it has been mentioned in the literature that a <5 mm step-off on CT scan is not detectable on simple X-ray22 (figure 4).

Figure 4.

A radiological comparison between standard X-ray and CT scan (adapted from Haller et al 22).

We can thus wonder if standard X-ray alone is the best radiological option to evaluate the radiological anatomical reduction precisely. This could represent a significant limitation for clinicians in comparing surgical techniques22 and create some major difficulties in choosing the best option to treat these patients.

We decided to use CT scan to analyse the postoperative radiological step-off reduction. Giving the fact that the lack of any visible step-off would reflect an optimal reduction on standard X-ray and that CT scan would be able to detect in this situation a 5 mm residual step-off, our primary endpoint is defined as the proportion of patients showing an optimal reduction with <5 mm residual step-off. This criterion will be measured by CT scan and assessed by an independent imaging core lab.

We will perform the CT scan 48 hours after the surgery in order to reduce the bias by avoiding loss of contact with the patients; keeping the operated patient blinded from the operative technique; assessing the potential failure of osteosynthesis or osteonecrosis; checking the compliance or non-compliance of the operator instructions.

Limitations

We identify two factors which could bias endpoint evaluations: (1) regarding intervention, even if surgeons will be trained on tibial tuberoplasty before their participation, we cannot guarantee that all surgeons will have the same level of control of this technique. In addition, medial or lateral tibial plateau fractures are accepted in this protocol and osteosynthesis and cavity filling are free. These three elements may influence tibial plateau fracture reduction and its impact on clinical outcomes. (2) Regarding blindness, it can be ensured for primary endpoint as evaluation will be done by an independent imaging core lab. However, for secondary endpoints, investigators could be aware of the technique due the patient’s interview after 48 hours, or due to site organisation.

Expected benefits

For the patients randomised in the tibial tuberoplasty arm, the expected benefits over the short and medium term are:

Earlier knee range of motion recovery, less stiffness. Knee range of motion is the direct reflection of functional capacity. For example, 83° allow for going up stairs, 90° allow for going down stairs and 93° allows for getting up from a chair.

Improvement of quality of life and functional impact.

Reduction of the time without weight-bearing.

Reduction of acute and chronic pain.

Reduction of the risk of surgical revision and infection of the surgical site.23

Reduction of complications in conjunction with confinement to bed (particularly in elderly persons).

Treatment of any associated meniscal or ligament injuries during the same surgery, which affect the functional prognosis over the shorter term.

Early resumption of activities.

Reduction of comorbidities connected with the use of iliac crest grafts.

Aesthetic benefits due to the size of the incisions.

The medical–economic benefits expected over the short and medium term are overall reductions of the cost of treatment of these patients taking into consideration the following factors: earlier resumption of social and professional activities; reduction of the time in hospital (absence of minimally invasive Redon drain no longer limits discharge to D3); reduction of painkiller consumption and physical therapy.

Ethics and dissemination

Legal obligations and approval

Sponsorship has been agreed by Poitiers University Hospital, Research and Innovation Department.

This clinical trial has been categorised as a class 2 human research study, with minimal constraints and risks, according to the French Jardé law. So, study protocol (V4—17 July 2018), information notice and informed consent form have been approved by the French ethics committee Ile-De-France X and sent for information to the French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ref protocole 24–2018 or 2018-A01027-48). Any substantial modification to study documents must obtain approval of ethics committee before its implementation. The study will be conducted in accordance with current International Conference on Harmonisation GCP guidelines, Declaration of Helsinki and standard operating procedures. Design, conduct and analysis will adhere to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement.

Dissemination policy

Poitiers University Hospital is the owner of the data. The data cannot be used or disclosed to a third party without its prior submission.

The results of the study will be released to the participating physicians, referring physicians and medical community no later than 1 year after the completion of the trial, through presentation at scientific conferences and publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Study status

The recruitment is planned to start in October 2018 and is expected to be completed in October 2019. It is anticipated that primary endpoint findings will be available at the beginning of 2020.

The 12 participating sites are, all in France: University Hospital of Poitiers, University Hospital of Pitié-Salpétrière, University Hospital of Fort de France, University Hospital of Versailles, University Hospital of Amiens, University Hospital of Nantes, University Hospital of Ambroise Paré, University Hospital of Tours, University Hospital of Rennes, University Hospital of Angers, University Hospital of Brest and University Hospital of Rouen.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: TV, L-EG, AG, FK and PR contributed to the development of tibial tuberoplasty. TV is the national coordinator of this study, supported by OM, MR and CB. PI helped to design the trial and provided expertise on statistics and methodology. ID-Z provided expertise on heatlh-economic aspects and GH on image processing and analysis for primary endpoint evaluation. TV, OM, MR and PR designed the trial and drafted the manuscript. CB drafted the manuscript. AG, GH, PI, ID-Z, FK and L-EG revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study received in 2018 funding from the French public health services ‘Direction Générale de l’Offre de Soins (DGOS)’ through a National Hospital Clinical Research Program. As recommended by the DGOS, Medtronic will provide kyphoplasty kits needed to conduct the study.

Competing interests: TV has received consultancy honoraria from Medtronic and Depuy-Synthes. PR is a consultant for Medtronic. He also received honoraria for medical training and research grants from Medtronic. ID-Z has received grants from ministry of health. All other coauthors (OM, CB, MR, GH, AG, L-EG, PI and FK).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Site Internet. Accès aux bases PMSI. Available: http://www.atih.sante.fr/bases-de-donnees/commande-de-bases?secteur=MCO

- 2. Schatzker J, McBroom R, Bruce D. The tibial plateau fracture. The Toronto experience 1968--1975. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979;(138):94–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young MJ, Barrack RL. Complications of internal fixation of tibial plateau fractures. Orthop Rev 1994;23:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu C-J, Chang W-N, Wong C-Y. Surgical treatment of tibial plateau fracture in elderly patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2001;121:67–70. 10.1007/s004020000145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roßbach BP, Faymonville C, Müller LP, et al. [Quality of life and job performance resulting from operatively treated tibial plateau fractures]. Unfallchirurg 2016;119:27–35. 10.1007/s00113-014-2618-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giannoudis PV, Tzioupis C, Papathanassopoulos A, et al. Articular step-off and risk of post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Evidence today. Injury 2010;41:986–95. 10.1016/j.injury.2010.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volpin G, Dowd GS, Stein H, et al. Degenerative arthritis after intra-articular fractures of the knee. long-term results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990;72-B:634–8. 10.1302/0301-620X.72B4.2380219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vendeuvre T, Babusiaux D, Brèque C, et al. Tuberoplasty: minimally invasive osteosynthesis technique for tibial plateau fractures. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99(4 Suppl):S267–S272. 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burdin G. Arthroscopic management of tibial plateau fractures: surgical technique. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99(1 Suppl):S208–S218. 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Durakbasa MO, Kose O, Ermis MN, et al. Measurement of lateral plateau depression and lateral plateau widening in a Schatzker type II fracture can predict a lateral meniscal injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:2141–6. 10.1007/s00167-012-2195-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hashemi J, Chandrashekar N, Gill B, et al. The geometry of the tibial plateau and its influence on the biomechanics of the Tibiofemoral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:2724–34. 10.2106/JBJS.G.01358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canale ST, Beaty JH, Campbell WC, et al. Campbell’ s operative orthopaedics: [get full access and more at ExpertConsult.com. 12th edn Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier, Mosby, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hannouche D, Duparc F, Beaufils P. The arterial vascularization of the lateral tibial condyle: anatomy and surgical applications. Surg Radiol Anat 2006;28:38–45. 10.1007/s00276-005-0044-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boisrenoult P, Bricteux S, Beaufils P, et al. [Screws versus screw-plate fixation of type 2 Schatzker fractures of the lateral tibial plateau. Cadaver biomechanical study. Arthroscopy French Society]. Rev Chir Orthopédique Réparatrice Appar Mot 2000;86:707–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kidiyoor B, Kilaru P, Rachakonda KR, et al. Clinical outcomes in periarticular knee fractures with flexible fixation using far cortical locking screws in locking plate: a prospective study. Musculoskelet Surg 2018:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trenholm A, Landry S, McLaughlin K, et al. Comparative Fixation of Tibial Plateau Fractures Using ??-BSM???, a Calcium Phosphate Cement, Versus Cancellous Bone Graft. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:698–702. 10.1097/01.bot.0000183455.01491.bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belaid D, Vendeuvre T, Bouchoucha A, et al. Utility of cement injection to stabilize split-depression tibial plateau fracture by minimally invasive methods: a finite element analysis. Clin Biomech 2018;56:27–35. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim G, Jung H-J, Lee H-J, et al. Accuracy and reliability of length measurements on three-dimensional computed tomography using open-source OsiriX software. J Digit Imaging 2012;25:486–91. 10.1007/s10278-012-9458-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mustonen AOT, Koivikko MP, Kiuru MJ, et al. Postoperative MDCT of tibial plateau fractures. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:1354–60. 10.2214/AJR.08.2260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duffy JC. Modern epidemiology Kenneth J. Rothman, Little, Brown & Co, Boston, 1986. No. of pages: 358. Price: £33.90. Stat Med 1988;7:818 10.1002/sim.4780070712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gicquel T, Najihi N, Vendeuvre T, et al. Tibial plateau fractures: reproducibility of three classifications (Schatzker, AO, Duparc) and a revised Duparc classification. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2013;99:805–16. 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haller JM, O’Toole R, Graves M, et al. How much articular displacement can be detected using fluoroscopy for tibial plateau fractures? Injury 2015;46:2243–7. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Colman M, Wright A, Gruen G, et al. Prolonged operative time increases infection rate in tibial plateau fractures. Injury 2013;44:249–52. 10.1016/j.injury.2012.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pizanis A, Garcia P, Pohlemann T, et al. Balloon tibioplasty: a useful tool for reduction of tibial plateau depression fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2012;26:e88–93. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31823a8dc8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Panzica M, Suero EM, Omar M, et al. Navigated reconstruction of tibial head depression fractures by inflation osteoplasty. Technol Health Care 2014;22:115–21. 10.3233/THC-130765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Craiovan BS, Keshmiri A, Springorum R, et al. [Minimally invasive treatment of depression fractures of the tibial plateau using balloon repositioning and tibioplasty: video article]. Orthopade 2014;43:930–3. 10.1007/s00132-014-3019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ziogas K, Tourvas E, Galanakis I, et al. Arthroscopy assisted balloon osteoplasty of a tibia plateau depression fracture: a case report. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:411–4. 10.4103/1947-2714.166223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mayr R, Attal R, Zwierzina M, et al. Effect of additional fixation in tibial plateau impression fractures treated with balloon reduction and cement augmentation. Clin Biomech 2015;30:847–51. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ollivier M, Turati M, Munier M, et al. Balloon tibioplasty for reduction of depressed tibial plateau fractures: preliminary radiographic and clinical results. Int Orthop 2016;40:1961–6. 10.1007/s00264-015-3047-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doria C, Balsano M, Spiga M, et al. Tibioplasty, a new technique in the management of tibial plateau fracture: a multicentric experience review. J Orthop 2017;14:176–81. 10.1016/j.jor.2016.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang J-Q, Jiang B-J, Guo W-J, et al. Arthroscopic-assisted balloon tibioplasty versus open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) for treatment of Schatzker II–IV tibial plateau fractures: study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021667 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vendeuvre T, Grunberg M, Germaneau A, et al. Contribution of minimally invasive bone augmentation to primary stabilization of the osteosynthesis of Schatzker type II tibial plateau fractures: balloon vs bone tamp. Clin Biomech 2018;59:27–33. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.