Abstract

Introduction

Clinical guidelines recommend that patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) learn carbohydrate counting or similar methods to improve glycaemic control. Although systematic educating in carbohydrate counting is still not offered as standard-of-care for all patients on multiple daily injections (MDI) insulin therapy in outpatient diabetes clinics in Denmark. This may be due to the lack of evidence as to which educational methods are the most effective for training patients in carbohydrate counting. The objective of this study is to compare the effect of two different educational programmes in carbohydrate counting with the usual dietary care on glycaemic control in patients with T1D.

Methods and analysis

The study is designed as a randomised controlled trial with a parallel-group design. The total study duration is 12 months with data collection at baseline, 6 and 12 months. We plan to include 231 Danish adult patients with T1D. Participants will be randomised to one of three dietician-led interventions: (1) a programme in basic carbohydrate counting, (2) a programme in advanced carbohydrate counting including an automated bolus calculator or (3) usual dietary care. The primary outcome is changes in glycated haemoglobin A1c or mean amplitude of glycaemic excursions from baseline to end of the intervention period (week 24) between and within each of the three study groups. Other outcome measures include changes in other parameters of plasma glucose variability (eg, time in range), body weight and composition, lipid profile, blood pressure, mathematical literacy skills, carbohydrate estimation accuracy, dietary intake, diet-related quality of life, perceived competencies in dietary management of diabetes and perceptions of an autonomy supportive dietician-led climate, physical activity and urinary biomarkers.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Capital Region, Copenhagen, Denmark. Study findings will be disseminated widely through peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov Registry (NCT03623113).

Keywords: randomised controlled trial, type 1 diabetes, carbohydrate counting, basic carbohydrate counting, advanced carbohydrate counting, nutritional education

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study has a long-term follow-up and will provide knowledge on the effects of different levels of carbohydrate counting.

The study applies well-documented measures of glycaemic control as effect parameters.

The results obtained have applicability beyond Denmark and has the potential to be included in the recommendations in future guidelines.

A limitation is the lack of a dietary ‘untreated’ control group, however; it would be unethical not to offer standard dietary care for patients with type 1 diabetes.

The difference in the number of hours and type of dietary education and support between the groups may also influence the participants’ learning.

Introduction

Carbohydrate is the nutrient in our diet with by far the highest impact on plasma glucose levels. The total amount of carbohydrates consumed in a meal is the major predictor of the postprandial glucose response. Thus, monitoring dietary intake of carbohydrates is important to control postprandial glucose fluctuations, which may lead to clinical benefits such as a reduction in glucose variability, an improvement of glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and a reduction in diabetes-related complications.

Clinical guidelines in medical nutrition therapy recommend that patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) learn carbohydrate counting or similar experience-based methods to improve glycaemic control.1–4 Two levels of carbohydrate counting have been defined internationally with different learning objectives and increasing complexity; a basic and an advanced level.5 6 Basic carbohydrate counting (BCC) includes understanding of the relationship between food, physical activity and plasma glucose levels with special attention on consistency in the timing, type, amount and distribution of carbohydrate-containing foods consumed. Advanced carbohydrate counting (ACC) is targeting the patient who ideally masters BCC, is on intensive insulin therapy and prepared to learn how to adjust insulin according to carbohydrate intake. In the clinical guidelines and studies, the term ‘carbohydrate counting’ is often used synonymously with ACC, while the sole effect of BCC on glycaemic control is largely unknown. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that ACC can reduce HbA1c by up to 7 mmol/mol in adults with poorly controlled T1D.7–9 Despite this, systematic educating and training is still not offered routinely for patients on multiple daily injections (MDI) therapy in outpatient clinics in Denmark. This may be due to the lack of evidence as to which educational methods are the most effective for training patients in carbohydrate counting in terms of supporting patients in implementation and ongoing adherence to the use of carbohydrate counting as a tool for meal planning in their daily life.

Ideally, patients with T1D treated on MDI therapy need to be able to manage the following steps of calculation when using carbohydrate counting: (1) correct calculation of the total carbohydrate content in each meal according to portion sizes of each carbohydrate-containing food item (equal to BCC) and (2) correct calculation of insulin dose according to the amount of carbohydrates to be consumed using a carbohydrate-to-insulin ratio, an insulin sensitivity factor, and the current and target plasma glucose (equal to ACC). In other words, patients with diabetes need good mathematical literacy skills, including numeracy skills, to be able to practice the above-mentioned steps several times each day. Recent studies suggest that lower literacy and numeracy skills are associated with poorer portion size estimation, understanding of food labels, diabetes-related self-management abilities, diabetes control and increased body mass index.10–16 Other studies have found that patients with diabetes frequently assess their intake of carbohydrates inaccurately and this has been associated with a poorer HbA1c.17–19 Particularly mixed meals, high-calorie foods and larger portion sizes resulted in inaccurate carbohydrate estimation. One study also found that underestimation of carbohydrate-rich meals was associated with higher daily plasma glucose variability in adults with T1D.20 Thus, assessment of numeracy skills is highly relevant to ensure that a nutritional education programme address patients with low literacy and numeracy. This may be done by numeracy-focused educational exercises and materials or hands-on learning.

In recent years, technological innovations including applications (apps) for smartphones have been introduced to reduce the complexity of carbohydrate counting and possibly compensate for poor numeracy skills. So far, no technological devices can replace the patients’ self-estimations of the carbohydrate content in most meals, for example, in mixed meals (addressing step 1). RCTs have demonstrated that ACC supported by the use of automated bolus calculator (ABC) software to assist insulin dose decision-making (addressing step 2) compared with unassisted ACC significantly improves HbA1c and treatment satisfaction in patients with T1D treated with MDI.21–23 However, a recent exploratory study found that lower numeracy skills were associated with smaller reductions in HbA1c after a 12-month education programme in ACC with no benefit from the use of an ABC compared with manual calculations.24 These findings support the need for more intensified dietary education in BCC before learning ACC. Additionally, the concept of ACC may not be useful in all patients with T1D on MDI therapy because of potential patient barriers, lack of motivation to learn the method and low levels of education, literacy or numeracy skills. Other barriers include lack of appropriate learning environments to promote behavioural change and availability of trained dietitians to facilitate the learning process.25 In a study of patients with diabetes, perceived competence was predicted by the degree to which the patients experienced the healthcare climate to be autonomy supportive, and perceived competence at carrying out the treatment in turn predicted HbA1c.26 Group-based approaches with practised-focused dietary education compared with individual dietary counselling have been practiced in some settings but are underinvestigated.27 In line with this, we are currently carrying out an RCT based on this protocol.

Aim

The aims are to examine the effectiveness of two different group-based dietitian-led practise-focused educational approaches for dietary self-management compared with the standard nutrition education on glycaemic control in patients with T1D. The BCC concept aims at improving carbohydrate counting accuracy and day-to-day consistency of carbohydrate intake (the BCC intervention) and the concept of ACC aim at improving prandial insulin dose accuracy using an ABC (the ABC-ACC intervention).

Methods and analysis

Study design

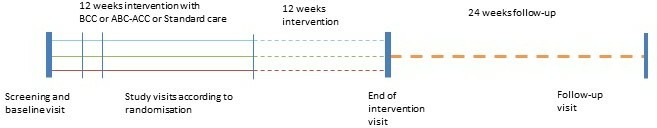

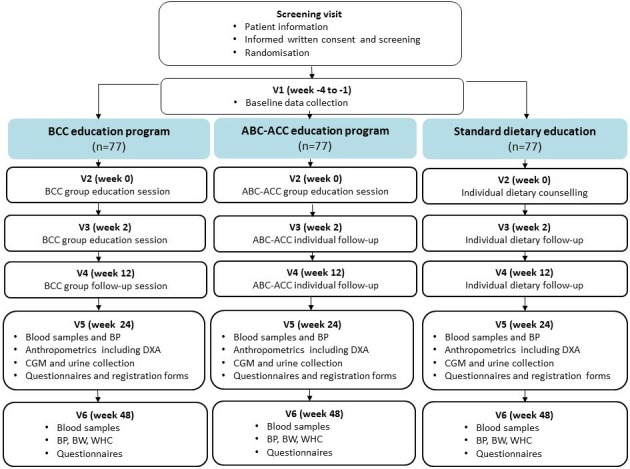

The study is as a randomised controlled intervention trial with a parallel-group design (see figure 1). The study duration is 48 months for each participant and includes up to seven visits at the study site (see figure 2). All participants will be instructed to maintain their habitual lifestyle in all other aspects than their diet, for example, keeping the same level of physical activity during the study period. All participants will be instructed to follow their regular diabetes care in the hospital, which usually includes 4 yearly visits with a diabetologist (endocrinologist) and 1 yearly consultation with a diabetes nurse. Participants will be instructed not to receive any further dietary education during the study period. Close relatives can participate in the dietary education in all three study groups if the participant needs support to manage dietary changes.

Figure 1.

Study design. ABC-ACC, advanced carbohydrate counting with an automated bolus calculator; BCC, basic carbohydratecounting.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the intervention. ABC-ACC, advanced carbohydrate counting with an automated bolus calculator; BCC, basic carbohydrate counting; BP, blood pressure; BW, body weight; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; DXA, dual-energy-X-ray absorptiometry; V, visit; WHC, waist-hip circumference.

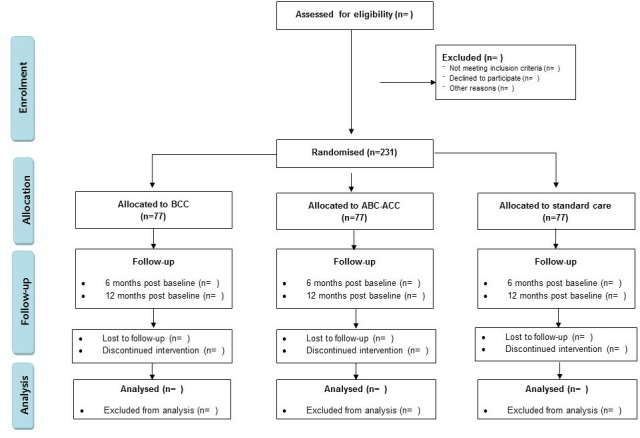

The study flow is presented in figure 3. The study follows the guidelines of Standard Protocol Items for Randomised Trials.

Figure 3.

Study flow diagram. The planned flow of participants through the stages of the study. ABC-ACC, advanced carbohydrate counting with an automated bolus calculator; BCC, basic carbohydrate counting.

Setting

The study will be carried out in the outpatient diabetes clinic at Steno Diabetes Center Copenhagen (SDCC) in Gentofte, Denmark.

Recruitment and consent

As a temporary supplementary treatment initiative, SDCC offers courses in BCC and ABC-ACC for all patients with T1D treated in the capital region of Denmark. Participants for the current study will be recruited among patients signing up for these courses or patients directly referred to one of the courses or the study by a healthcare professional (diabetologist, diabetes nurse or dietitian) from SDCC or from a Steno Partner hospital in the capital region. A course administrator at SDCC will contact all interested or referred patients by telephone and provide information about the study. In addition, potential study participants will be recruited through information on sdcc.dk and other electronic media or patient-related networks. If the patient is interested in the study, the patient will receive the written patient information by mail or email. If interested in study participation, the study investigator/study personnel will schedule a personal meeting for oral patient information, offering the possibility of bringing a confidant. The patient will be given time to discuss any questions and will be informed that he/she has at least 24 hours to decide on participation in the study. If the patient decides to participate in the study, the patient and the study investigator/study personnel will sign the written informed consent, and the investigator/study personnel will perform a screening. If all inclusion criteria are fulfilled and none of the exclusion criteria are met, the patient will be included in the study and randomised to one of three groups. Patients who decline to participate or do not meet the inclusion criteria will continue their usual care in an outpatient diabetes clinic and will be offered to participate on a BCC or ACC course if they still wish to do so. Participants will be informed that participation is voluntary, and that they may withdraw their consent at any time.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with T1D between 18 and 75 years of age with a diabetes duration above 12 months and with an initial HbA1c of 53–97 mmol/mol on MDI therapy with a basal-bolus insulin regime are eligible for the study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients are excluded if they have other types of diabetes than T1D, are practicing carbohydrate counting as judged by the investigator, have a low daily intake of carbohydrates (defined as <25 E% or 100 g/day), have participated in a BCC group programme within the last 2 years, use an insulin pump or plan to have an insulin pump within the study period, use split-mixed insulin therapy, use an ABC, have gastroparesis, have uncontrolled medical issues affecting the dietary intake as judged by the investigator or a medical expert. Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding or have plans of pregnancy within the study period are also excluded. Furthermore, patients who are either participating in other clinical studies or are unable to understand the informed consent and the study procedures will be excluded.

Randomisation

Participants eligible for inclusion in the study will be randomly allocated in a 1:1:1 ratio to one of the three groups (BCC, ABC-ACC or control) using a computer-generated randomisation in the software programme REDCap. The randomisation is done by stratifying participants based on sex and HbA1c at baseline. The randomisation is done in blocks in order to ensure an equal number of participants in each group.

Intervention groups

The BCC programme consists of two sessions of 3 hours and a follow-up group session of 2 hours. The BCC programme uses trained dietitians following a planned curriculum which include experience-based learning with problem-solving exercises, hands-on activities, short theoretical presentations, discussions of motivational aspects and coping strategies. The BCC programme integrates peer modelling, skills development, goal setting, observational learning and social support into the programme content and activities. The training includes identifying carbohydrates in food, reading carbohydrate tables, calculating the carbohydrate content from food labels, tables and apps and use of a personalised carbohydrate plan with guiding suggestions for daily intake of carbohydrates at meals based on 4 days of personal dietary recording performed before the programme including plasma glucose measurements and prandial insulin dosages taken. An app (Diabetes og Kulhydrattælling. The Danish Diabetes Association, Pragma soft A/S, available in Google Play and AppStore) will be introduced to support estimation and calculation of carbohydrates and assist in simple insulin dose determination if participants choose to consume more carbohydrates at a meal than suggested in their personal carbohydrate plan.

The ABC-ACC programme consists of a 4-hour group session and two individual follow-up sessions (two 45 min sessions). The programme uses trained dietitians with supervision by a medical doctor and follows a planned curriculum. The ABC-ACC intervention is a group-based educational programme based on the well-described BolusCal concept.28 The programme includes fast training in BCC, ACC and bolus calculation using an ABC (mySugr Pro. Roche, available in Google Play and AppStore) taking insulin onboard, insulin sensitivity factor and differentiated carbohydrate-to-insulin ratios during the day into account. The carbohydrate-to-insulin ratios are based on 7 days of personal dietary recording including plasma glucose measurements and prandial insulin dosages taken. The ABC-ACC programme contains theoretical and practical training. The teaching is based on theory and examples from everyday life with T1D and the educators help the participants with their specific diabetes-related problems and try to find appropriate practical solutions together with the participant.

Control group

Participants randomised to the control group receive current standard outpatient nutrition education in T1D. This includes individual guidance by a trained dietitian, with one initial 60 min dietary counselling session and two individual 30 min follow-up session. The individual guidance is based on the overall treatment goal and the defined personal dietary goals for behavioural change according to patient preferences. Dietary guidance includes topics such as carbohydrate sources (eg, practicing glycaemic index and dietary fibre intake) and amounts of carbohydrates or more general dietary recommendations according to patient needs.

Delivery of dietary education

The educational programme in both the standard treatment group and the intervention groups will be delivered by the same study dietitians. The dietitians have been trained by the PI (Bettina Ewers) in what to deliver in each study-arm according to the study protocol and in case of doubt, they will discuss each case with the PI to make sure that they provide the correct guidance to all participants. Data on which of the dietitians each participant has been exposed to during the trial is registered for later data analysis. Additionally, all study dietitians have an interest in providing the best possible dietary guidance irrespective of it being the standard treatment or the two intervention concepts being tested.

Data collection

All study data will be collected at the three visits with clinical examinations (baseline, after 6 and 12 months). Data will be obtained from a self-reported patient questionnaire, electronic medical records and the physical examinations conducted by the study investigator or study personnel. All questionnaire data will be collected electronically using the software system REDCap according to local standards for research projects in the capital region of Denmark. In addition, all sources will be registered in this database. Data generated and stored for specific equipment (eg, dual-energy-X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) data stored in the DXA scanner software database), electronic medical data (blood and urine measurements, glucose-lowering and lipid-lowering medicine), data from iPro2 CGM using software from Medtronic (Northridge, California, USA) to download continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) measurements, dietary data on total energy and nutrients based on calculations from the software system Vitakost will be added to the database in REDCap on an ongoing basis and at the end of study.

The primary outcome is the difference in mean HbA1c or mean amplitude of glycaemic excursions (MAGE) from baseline to end of the intervention (week 24) between and within each of the three study groups (BCC, ABC-ACC and control).

A schematic overview of outcomes measurements is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Schematic overview of outcomes measured

| Week no from start of intervention | –4 to –1 | 12 | 24 | 48 |

| HbA1c | X | X | X | X |

| Plasma lipids | X | X | X | |

| Body weight | X | X | X | |

| Height | X | |||

| Waist and hip circumference | X | X | X | |

| Blood pressure | X | X | X | |

| Blood samples, fasting | X | X | X | |

| Urine samples for 4 days* | X | X | ||

| Glucose variability (CGM) including PG diary for 6 days* | X | X | ||

| Body composition (DXA) | X | X | ||

| Prescribed lipid-lowering and glucose-lowering medication | X | X | X | |

| F: dietary registration for 4 days* | X | X | ||

| Q: diet-related quality of life | X | X | X | |

| Q: perceived competencies in diabetes | X | X | X | |

| Q: healthcare climate | X | X | ||

| Q: carbohydrate estimation accuracy | X | X | X | |

| Q: mathematical literacy | X | X | X | |

| Q: demographic data | X | |||

| Q: physical activity | X | X | X |

*Measured in the days following the study visits.

CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; DXA, dual-energy-X-ray absorptiometry; F, forms; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; PG, plasma glucose; Q, questionnaire.

Secondary outcomes are listed below

Clinical parameters

Body weight, body composition (measured by DXA), waist and hip circumference, blood pressure, type and dose of prescribed glucose-lowering and lipid-lowering medication, other parameters of plasma glucose variability including time in range (3.9–10.0 mmol/L), % time spent in hypoglycaemia (<3.9 mmol/L), % time spent in hyperglycaemia (eg, >10.0 mmol/L) and SD of mean plasma glucose assessed from CGM measurements.

Blood and urine samples

HbA1c (after 12 and 48 weeks), plasma lipids (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, total cholesterol, free fatty acids and triglycerides), alanine aminotransferase, urine albumin/creatinine ratio and urinary biomarkers based on three daily midstream urine spots collected for 4 days.

Patient-reported outcomes

Diet-related quality of life, perceived competencies in diabetes, healthcare climate, carbohydrate estimation accuracy, mathematical literacy skills, physical activity and demographic questions. The six questionnaires used are as follows.

Diabetes diet-related quality of life questionnaire

The diabetes diet-related quality of life questionnaire (DDRQOL) is a 31-item scale which has been validated in patients with diabetes.29 The scale is designed to determine the quantitative and qualitative satisfaction with diet and the degree of restriction of daily life and social life functions due to the dietary changes. A forward translation and cultural adaption of the DDRQOL was done by a Japanese-Danish interpreter with a background as a clinical dietitian and an expert panel of six clinical dietitians working with diabetes. This was followed by a pilot testing by 10 patients with diabetes.

Perceived Competencies in Diabetes Scale

The Perceived Competencies in Diabetes Scale includes four items that reflect participants’ feelings of competence about engaging in a healthier behaviour and participating in a nutritional education programme. Forward and backward linguistic translation from English to Danish has been done according to standard procedures in 2001 under the guidance of Professor Vibeke Zoffmann.

Healthcare Climate Questionnaire

The Healthcare Climate Questionnaire chosen in this study is a 5-item short form of the originally validated 15-item measure that assesses patients’ perceptions of the degree to which dieticians are autonomy supportive vs controlling in providing dietary treatment.

Carbohydrate photographic questionnaire

The carbohydrate photographic questionnaire (CPQ) is an electronic questionnaire assessing diabetes patients’ abilities to estimate portion sizes of 11 commonly eaten high-carbohydrate foods correctly. The CPQ has been developed and validated against real food in 87 patients with T1D. A manuscript of these study results has been submitted (Ewers et al, unpublished).

Mathematical literacy questionnaire

A 10-item test with modified questions from the nutrition domain of the Diabetes Numeracy Test (DNT)30 was designed and feasibility tested to investigate mathematical literacy including numeracy skills (addition, subtraction, division and multiplication) which are essential for understanding numbers and applying mathematical skills in daily life, for example, for calculating carbohydrates.

International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form

The Danish version of the InternationalPhysical Activity Questionnaire Short Form31 will be used to assess changes in level of physical activity during the study period.

Demographic data

Self-reported demographic questions include level of education, occupation, marital status, household composition and yearly income.

Dietary data

Four days of weighed dietary food records collected at baseline and 6 months after baseline. Dietary records will be calculated using the software system Vitakost where nutrient and energy calculations are based on the Danish national food database. The dietary food records are used to estimate total energy intake (kJ/day), intake of carbohydrates, protein and fat (g/day and g/meal), added sugar (g/day) and total dietary fibre intake (g/day). The dietitian performing the analysis of the food records only have access to the study ID number and participant initials.

Baseline data (from the electronic medical record)

Type of diabetes, diabetes duration, use of an open CGM, use of Freestyle Libre, gender, age, smoking status, medical conditions, total number of visits at a diabetologist and diabetes nurse and dietician during and one year prior to the study period.

Data analysis plan

The trial is ongoing. The patient recruitment started in October 2018 and is expected to be completed by October 2021.

Sample size calculation

A power calculation was conducted based on the primary outcome measures HbA1c and MAGE. Allowing for an estimated drop-out rate of 20% and subgroup analyses the sample size was planned to include a total of 231 patients in the study (77 in each arm). This was based on a sample size calculation which suggested that including 64 participants in each of the study groups would give 80% power to detect a clinically meaningful difference in change in HbA1c of 3.5 mmol/mol between the BCC group versus the control group or the ABC-ACC group versus the control group with a 5% significance level using a two-sided test and an estimated SD of 7 mmol/mol. This SD has previously been used for sample size calculations in ACC trials21 and was similar to what was found in an evaluation of previous conducted BCC courses at SDCC on mean changes and SD of HbA1c after 6 months among completers with T1D (n=185). MAGE has only been used as an outcome measure of glucose variability in a few randomised controlled dietary intervention studies of patients with diabetes32 33 showing differences in changes in MAGE up to 4.8 mmol/L (SD: 1.0) after a 12-week carbohydrate counting intervention,32 but is regularly used in other clinical studies evaluating glucose variability. By including 77 participants in each study group, we will have a power of 80% (alpha level of 0.05) in a two-sided test to detect a clinically meaningful difference in the change in MAGE during the intervention period (week 24) of ≥0.35 mmol/L (SD 0.7 mmol/L) between the study groups.

Statistical methods

Analysis and reporting of the study results will follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials.34 Results will be presented as means (SD) for normally distributed variables and as medians (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be used to compare baseline data between the three study groups for normal data and Kruskal-Wallis H test for non-normal data. Paired samples t-test will be used for within group comparison for normal data and Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-normal data. Mixed-effect models will be used to test differences in outcomes from baseline to follow-up to take repeated measurements into account. If model assumptions cannot be met even after logarithmic transformation, non-parametric tests will be used. Examinations of the relevant diagnostic plots, including QQ-plots, will be used to evaluate normality of the residuals.

The baseline demographics as well as clinical and diabetes-related characteristics of the intervention and the control groups will be presented and compared. The average changes between baseline and week 24 and 48 in primary and secondary outcomes will be calculated for each of the three groups. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis will be performed as the primary analysis on all primary and secondary outcomes after the last participant has ended participation. Missing values will be handled with a last observation carried forward approach for ITT analysis with the use of the multiple imputation approach in a sensitivity analysis. Per protocol analysis will only be performed in case of sensitivity testing. Metabolic patterns will be tested with multivariate statistics. Adjustment for relevant confounders will be performed including adjustment for the stratified variables. Heterogeneity in responsiveness to the interventions will be tested by dividing each intervention group into smaller groups based on data distribution (medians) or clinically meaningful cut-points. Two-sided tests will be used. P values of <0.05 are considered significant. The statistical programmes SPSS version 22.0 and SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 or newer versions will be used for data analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were involved in developing the educational content of the BCC programme. Patients were not involved in setting the research questions or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing the study design. Information may be disseminated to the public via any media coverage of study findings.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted in accordance with the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki and to the regulations for Good Clinical Practice to the extent that this is relevant for non-medical studies. The study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov.

All health-related matters and sensitive personal data will be handled in accordance with the Danish ‘Act on Processing of Personal Data’. All health-related matters and sensitive personal data (blood test results and so on) will be depersonalised. All participants will be given a study number referring to their personal information, which will be stored securely and separately. Data will be stored in coded form for 10 years after last participant has attended the last visit, after which the data will be fully anonymised.

Data are owned by the investigators who are responsible for publishing the results. Positive and negative as well as inconclusive study results will be published by the investigators in international peer-reviewed journals, and all coauthors must comply with the Vancouver rules. BE will be responsible for writing the first draft of the manuscript based on the main study results as a first author under guidance by TV and JMB. The study results will be presented at relevant national and international scientific conferences and meetings and will be published in international peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BE conceived the original idea for this trial, planned the study design, performed the sample size calculations and wrote the first draft of the protocol manuscript. TV and JMB provided valuable input regarding trial design, planning and analytical considerations, and edited the first draft of the protocol manuscript. HUA has contributed intellectually to the protocol. All authors approved the final version of the clinical trial protocol. BE is the principle investigator and is responsible for correspondence with all authorities regarding the study and is responsible for the data collection (recruitment, screening and clinical study examinations), overall monitoring the trial and for conducting the statistical analyses. TV, JMB and HUA are supervisors and coinvestigators of this trial. Should any safety concerns arise during the conduct of the study these will be brought to the attention of HUA, TV and JMB by BE and will be carefully reviewed.

Funding: This work was supported by The Beckett Foundation (grant number 17-2-0957), the Axel Muusfeldts Foundation (grant no 2017-856) and the Novo Nordisk Foundation (no assigned grant number) as part of a supplementary treatment initiative at SDCC in 2018-2020. Roche has provided voucher codes for free use of the bolus calculator ‘MySugr Pro’ in the 12-month trial period for patients randomized to the ACC group in the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Capital Region, Copenhagen (#H-18014897) and has been approved for data storage by the Danish Data Protection Agency (journal no VD-2018–124, I-suite no 6367).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kliniske retningslinjer for behandling af voksne med Type 1 diabetes Sundhedsstyrelsen (Danish Health & Medicines Authority. Copenhagen, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rammeplan for diætbehandling AF type 1 diabetes Foreningen AF kliniske diætister (the association of clinical dietitians) 2011.

- 3. Mann JI, De Leeuw I, Hermansen K, et al. Evidence-Based nutritional approaches to the treatment and prevention of diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2004;14:373–94. 10.1016/S0939-4753(04)80028-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheard NF, Clark NG, Brand-Miller JC, et al. Dietary carbohydrate (amount and type) in the prevention and management of diabetes: a statement by the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care 2004;27:2266–71. 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gillespie SJ, Kulkarni KD, Daly AE. Using carbohydrate counting in diabetes clinical practice. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98:897–905. 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00206-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kulkarni KD. Carbohydrate counting: a practical Meal-Planning option for people with diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 2005;23:120–2. 10.2337/diaclin.23.3.120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell KJ, Barclay AW, Petocz P, et al. Efficacy of carbohydrate counting in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 2014;2:133–40. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70144-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fu S, Li L, Deng S, et al. Effectiveness of advanced carbohydrate counting in type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016;6:37067 10.1038/srep37067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schmidt S, Schelde B, Nørgaard K. Effects of advanced carbohydrate counting in patients with Type 1 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabet. Med. 2014;31:886–96. 10.1111/dme.12446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowen ME, Cavanaugh KL, Wolff K, et al. Numeracy and dietary intake in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2013;39:240–7. 10.1177/0145721713475841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cavanaugh K, Huizinga MM, Wallston KA, et al. Association of Numeracy and diabetes control. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:737–46. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-10-200805200-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huizinga MM, Beech BM, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Low numeracy skills are associated with higher BMI. Obesity 2008;16:1966–8. 10.1038/oby.2008.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huizinga MM, Carlisle AJ, Cavanaugh KL, et al. Literacy, Numeracy, and Portion-Size estimation skills. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:324–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marden S, Thomas PW, Sheppard ZA, et al. Poor numeracy skills are associated with glycaemic control in Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2012;29:662–9. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03466.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rothman RL, et al. Influence of patient literacy on the effectiveness of a primary Care–Based diabetes disease management program. JAMA 2004;292:1711–6. 10.1001/jama.292.14.1711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rothman RL, Housam R, Weiss H, et al. Patient understanding of food labels: the role of literacy and numeracy. Am J Prev Med 2006;31:391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bishop FK, Maahs DM, Spiegel G, et al. The carbohydrate counting in adolescents with type 1 diabetes (CCAT) study. Diabetes Spectrum 2009;22:56–62. 10.2337/diaspect.22.1.56 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mehta SN, Quinn N, Volkening LK, et al. Impact of carbohydrate counting on glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1014–6. 10.2337/dc08-2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smart CE, Ross K, Edge JA, et al. Can children with type 1 diabetes and their caregivers estimate the carbohydrate content of meals and snacks? Diabet Med 2010;27:348–53. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brazeau AS, Mircescu H, Desjardins K, et al. Carbohydrate counting accuracy and blood glucose variability in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2013;99:19–23. 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hommel E, Schmidt S, Vistisen D, et al. Effects of advanced carbohydrate counting guided by an automated bolus calculator in type 1 diabetes mellitus (StenoABC): a 12-month, randomized clinical trial. Diabet. Med. 2017;34:708–15. 10.1111/dme.13275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmidt S, Meldgaard M, Serifovski N, et al. Use of an automated bolus calculator in MDI-Treated type 1 diabetes: the BolusCal study, a randomized controlled pilot study. Diabetes Care 2012;35:984–90. 10.2337/dc11-2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ziegler R, Cavan DA, Cranston I, et al. Use of an insulin bolus advisor improves glycemic control in multiple daily insulin injection (MDI) therapy patients with suboptimal glycemic control: first results from the ABACUS trial. Diabetes Care 2013;36:3613–9. 10.2337/dc13-0251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmidt S, Vistisen D, Almdal T, et al. Exploring factors influencing HbA1c and psychosocial outcomes in people with type 1 diabetes after training in advanced carbohydrate counting. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2017;130:61–6. 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kawamura T, Takamura C, Hirose M, et al. The factors affecting on estimation of carbohydrate content of meals in carbohydrate counting. Clin Pediatr Endocrinol 2015;24:153–65. 10.1297/cpe.24.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1644–51. 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Toft U, Kristoffersen L, Ladelund S, et al. The effect of adding group-based counselling to individual lifestyle counselling on changes in dietary intake. The Inter99 study – a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2008;5 10.1186/1479-5868-5-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meldgaard M, Damm-Frydenberg C, Vesth U, et al. Use of advanced carbohydrate counting and an automated bolus calculator in clinical practice: the BolusCal ® training concept. International Diabetes Nursing 2015;12:8–13. 10.1179/2057331615Z.0000000002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sato E, Suzukamo Y, Miyashita M, et al. Development of a diabetes diet-related quality-of-life scale. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1271–5. 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huizinga MM, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, et al. Development and validation of the diabetes Numeracy test (DNT). BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:96 10.1186/1472-6963-8-96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee PH, Macfarlane DJ, Lam TH, et al. Validity of the International physical activity questionnaire short form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8 10.1186/1479-5868-8-115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bell KJ, Gray R, Munns D, et al. Clinical application of the food insulin index for mealtime insulin dosing in adults with type 1 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Technol Ther 2016;18:218–25. 10.1089/dia.2015.0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tay J, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Thompson CH, et al. Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:780–90. 10.3945/ajcn.115.112581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.