Abstract

Introduction

School canteens are the most frequently accessed take-away food outlet by Australian children. The rapid development of online lunch ordering systems for school canteens presents new opportunities to deliver novel public health nutrition interventions to school-aged children. This study aims to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a behavioural intervention in reducing the energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium content of online canteen lunch orders for primary school children.

Methods and analysis

The study will employ a cluster randomised controlled trial design. Twenty-six primary schools in New South Wales, Australia, that have an existing online canteen ordering system will be randomised to receive either a multi-strategy behavioural intervention or a control (the standard online canteen ordering system). The intervention will be integrated into the existing online canteen system and will seek to encourage the purchase of healthier food and drinks for school lunch orders (ie, items lower in energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium). The behavioural intervention will use evidence-based choice architecture strategies to redesign the online menu and ordering system including: menu labelling, placement, prompting and provision of feedback and incentives. The primary trial outcomes will be the mean energy (kilojoules), saturated fat (grams), sugar (grams) and sodium (milligrams) content of lunch orders placed via the online system, and will be assessed 12 months after baseline data collection.

Ethics and dissemination

The study was approved by the ethics committees of the University of Newcastle (H-2017–0402) and the New South Wales Department of Education and Communities (SERAP 2018065), and the Catholic Education Office Dioceses of Sydney, Parramatta, Lismore, Maitland-Newcastle, Bathurst, Canberra-Goulburn, Wollongong, Wagga Wagga and Wilcannia-Forbes. Study results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publications, reports, presentations at relevant national and international conferences and via briefings to key stakeholders. Results will be used to inform future implementation of public health nutrition interventions through school canteens, and may be transferable to other food settings or online systems for ordering food.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618000855224.

Keywords: intervention, RCT, nutrition, obesity, primary school, canteen

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will use a cluster randomised controlled trial design, a rigorous research design for assessing intervention effectiveness.

The evidence-based choice architecture intervention is embedded within an existing online canteen ordering system that is used by over 1200 schools across Australia, and processes over 13 million lunch orders per year.

The cost and cost-effectiveness of the intervention will be determined from a societal perspective giving transparency to the cost of implementation, providing policy makers with critical data to inform decision-making.

Actual food consumption will not be assessed; purchase data will serve as a proxy for food consumption.

Introduction

Dietary risk factors are a leading cause of death and disability internationally.1 Given dietary behaviours in childhood track into adulthood and are predictive of future chronic disease,2 improving child nutrition is a health priority in Australia and internationally.3 4 Schools provide an important setting for promoting healthy food consumption to children as they provide centralised access to almost every Australian child for prolonged periods, with children consuming almost 40% of their recommended energy intake while at school.5 Schools also represent a significant food provider. In New South Wales (NSW), 95% of primary-aged children attend a school with a canteen6 and 55% of students order their lunch from the canteen at least weekly, compared with 23% of students that eat a meal or snack from a fast-food outlet each week.6 The most frequently purchased menu items from canteens are often high in fat, sugar and salt7 with canteen purchases contributing an additional 200 kJ to energy consumed at school, compared with foods brought from home.5

While previous attempts to improve the school food environment have focused on changing the relative availability of unhealthy foods for sale at school,8–12 modifying other drivers of consumer behaviour represents an additional opportunity to improve children’s diet. For example, previous research has demonstrated that point-of-purchase interventions that involve nutrition labelling,13 manipulating the placement of menu items14 and the provision of purchasing prompts,15 nutritional feedback16 and incentives17 can influence the purchase of foods and drinks among children and adults. Despite the potential of behavioural strategies to encourage healthy purchasing, national and international studies of (non-online) canteens and cafeterias indicate that such strategies are underutilised in schools. The US School Health Policies and Practices Study of 544 elementary schools found few school cafeterias used strategies such as provision of nutritional feedback (60%) or item placement (10%–26%) or incentives (16%–17%) to encourage healthy purchasing.18 Furthermore, an Australian study of 203 primary schools found that only 43% reported labelling their canteen menus to identify healthy options.19

Canteen online ordering systems allow users to view, select and purchase food and drink menu items online, and represent a new approach for children to access food at school. They are becoming increasingly popular in Australia,20 with the leading supplier servicing over 1200 schools nationally and processing over 13 million lunch orders per year.21 These systems represent an attractive opportunity to apply a range of behavioural strategies that can reach large numbers of individuals at relatively low cost.22 Strategies including menu or product labelling, product placement and the provision of prompts and incentives are routinely used to influence purchase decisions by food retailers online.23 Furthermore, given these systems are centrally administrated, interventions delivered via these means may be more resistant to the transient nature of local canteen staffing, a common barrier to sustainable implementation of nutrition guidelines and interventions in this setting.24

We recently conducted a pilot trial that evaluated the use of strategies including traffic light menu-labelling, prominent placement of healthy menu items, provision of prompts to select healthy menu items, and reduced accessibility of less healthy items25 integrated into an online school canteen ordering system. The trial was undertaken in ten NSW primary schools over a 2 month intervention period and found that, compared with controls, intervention lunch orders were significantly lower in energy (−567 kJ), saturated fat (−2.37 g) and sodium (−228 mg) (all p<0.001).26 Given these promising findings, a larger trial is proposed and described in this protocol, which tests a greater range of intervention strategies, using a larger study sample and longer period of follow-up.

Study aim

The aim of the study is to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an online multi-strategy behavioural intervention in reducing the energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium content of primary school students’ online canteen lunch orders.

Methods and analysis

Study design and setting

The study will be conducted in government, independent and catholic schools in NSW, Australia, and will use a cluster randomised controlled trial design. Schools that currently use the ‘Flexischools’ online canteen ordering system will be randomised to either an intervention or usual practice control group. Intervention effectiveness will be assessed by comparing between-group differences at follow-up in the mean (1) energy (kilojoules), (2) saturated fat (grams), (3) sugar (grams) and (4) sodium (milligrams) contained in students’ online lunch orders, based on purchasing data that is automatically collected by the online canteen system. Both baseline and follow-up assessment periods will be conducted over one school term, of approximately 10 weeks’ duration, one calendar year apart.

Participants and recruitment

Schools

All NSW primary schools currently using the ‘Flexischools’ online canteen system27 will serve as the sampling frame (n=481). A list of all such schools has been supplied by the provider of the online canteen ordering system (here-after referred to as the ‘provider’) servicing over 1200 schools across Australia.21 One member of the research team will act as the recruitment coordinator and will manage recruitment and consent into the trial. Study information and consent forms will be mailed to the school principal and canteen manager at all potentially eligible schools from the sampling frame. Approximately 1–2 weeks later, the recruitment coordinator will make a follow-up phone call to speak with the school principal and/or canteen manager about the research and confirm school eligibility using procedures previously undertaken by the research team. Principal consent will be required to enable school participation in the trial and to enable the researchers to access the school’s canteen purchasing data from the provider. Principals will retain the right to discontinue their participation in the study and withdraw the school from the trial at any point.

School eligibility criteria

Given canteen guidelines differ from state to state and between primary and secondary schools, only NSW primary schools (serviced by the provider) will be included in the study.

Schools will be approached via mail and telephone to participate. Schools that can be identified (ie, from a published list or where reliable data can be sourced about their operation) as having an externally licensed commercial canteen operator will be removed from the sample due to the potential for contamination between schools. Schools that enrol both primary (kindergarten to grade 6) and secondary (grade 7 to 12) school students will only be included where there is a separate canteen menu for primary school students, due to differences in the NSW canteen guidelines for primary versus secondary schools.

Users

Users of the online canteen system could be students or parents/carers who place orders on behalf of their children. Schools that use an online canteen system can also choose to retain the traditional method for placing lunch orders (ie, writing the lunch order on a paper bag and submitting directly to the canteen) in addition to offering online ordering. To submit an online order, users access the provider’s website from their mobile device or computer. They then select the day and meal for which they want to place an order (eg, Tuesday, lunchtime), and they are then shown the full list of food and drink menu items that are available for that meal. To order, users click on menu items and then pay via a credit or debit card or PayPal. Data supplied from the provider suggests that on average, 30%–40% of students in schools they service have an account set up to enable online canteen ordering and have ordered within the last 30 days.

User eligibility criteria

Students who have an online lunch order submitted during the baseline data collection period are eligible for inclusion in the trial. As the follow-up data collection period occurs in the subsequent school year, only students in kindergarten to grade 5 (ages 5–11) will be included at baseline, in order to ensure they are available for follow-up. Given not all schools offer online ordering for recess foods, recess purchases will not be included in the analysis. Furthermore, only lunch orders submitted via mobile devices (approximately 70%) will be included in the analysis as the desktop version is due to be phased out by the provider. As such orders submitted via the desktop website, or orders submitted at the canteen will not be included in the analysis.

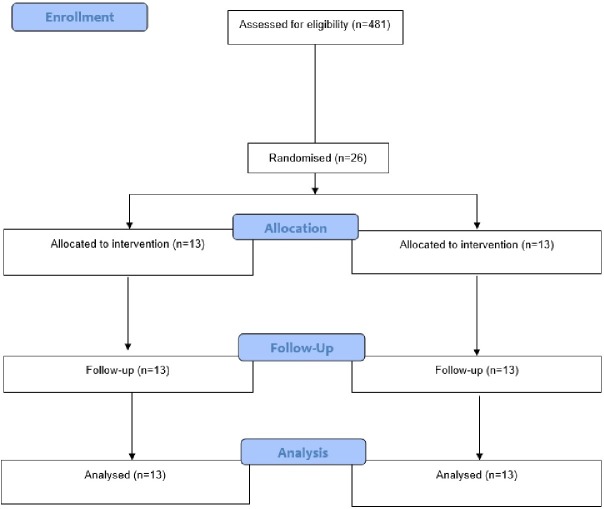

Randomisation and blinding

Following school recruitment and baseline data collection, schools will be randomised by an independent statistician using a randomised number function in Microsoft Excel in a 1:1 ratio to either an intervention or control group (see figure 1). Block randomisation will be employed to ensure group allocation is approximately equal, with block size randomly varying between 2 and 4. Given evidence that there are differences in the implementation of canteen guidelines between more and less advantaged areas and between government and non-government school sectors,28 the randomisation procedure will be stratified by the socioeconomic status of a school locality (based on postcode and dichotomised into most vs least advantaged), and by school sector (government vs catholic vs independent). Following random allocation to either intervention or control group, the online strategies will be applied to the canteen menus of each intervention school by accessing the canteen manager portal within the online canteen system. A research assistant will perform a quality check on the live website to ensure all strategies have been correctly applied. Due to the difficulty in blinding users to the changes introduced as part of the intervention, the study will be conducted as an open trial. However, the dietitians conducting the menu assessment will be blind to group allocation via the removal of all identifiable information from menus prior to assessment.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flowchart showing the progress of participating schools through the trial

Intervention

A multi-strategy behavioural intervention will be integrated into the existing online canteen system27 of intervention schools as described below. The intervention seeks to encourage the purchase of healthier foods and drinks for school canteen lunch orders, that is, items lower in energy, saturated fat, sugar and/or sodium, consistent with the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy. The intervention will be operational across the entire study period until the end of follow-up data collection (12 months post baseline). Research assistants will be responsible for managing the delivery of the online strategy to the intervention group, liaising with schools and communicating any necessary changes throughout the study. All users of the online canteen ordering system at intervention schools will be exposed to the intervention. Controlled access to the intervention strategies by the provider will prevent potential intervention contamination between groups.

Intervention conceptual framework

The intervention is based on the principles of choice architecture, which suggests that behaviour can be influenced by the environment in which choices are made,29 with choice architecture interventions typically altering micro-environments (eg, online applications/‘apps’) in order to cue healthier choices.30 The intervention for this trial was guided by the choice architecture typology proposed by Hollands and colleagues.29 Strategies that performed well against the following criteria were included in the intervention: (1) strategies that were supported by evidence of effectiveness from food-service settings (including the pilot trial),26 (2) strategies that were considered effective and acceptable in surveys of school stakeholders including principals and parents,20 31 (3) strategies that were able to be feasibly operationalised in an online environment and (4) strategies that were amenable to implementation at scale (ie, low cost and high reach). Furthermore, given research suggests that parents are involved in 68% of fast food purchase decisions for their children,32 a strategy was deliberately included that targeted child users of the system (incentives).

Intervention strategies

The strategies that form the intervention have all been shown to support healthier choices in food-service settings.13–17 33 The choice architecture strategies from the pilot trial will be retained25 and additional strategies, including provision of feedback and incentives will be added. Based on feedback from the pilot trial, availability (menu composition) and pricing strategies will be included to support the canteen manager to apply the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy and to allay any concerns that implementing the intervention will undermine canteen revenue. These strategies will be delivered via a tailored feedback report that will be sent to both the canteen manager and school principal and discussed in a brief feedback call from the research assistant with the canteen manager. The written and verbal feedback will be provided at one time point, immediately prior to the application of the choice architecture strategies within the online canteen system.

Availability of healthy foods (menu composition)

In 2017, the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy was revised and the classification system used to indicate the relative healthiness of canteen foods and drinks was changed. Classification thresholds were set for the menu item content of energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium, as well as serving sizes,34 with all menu items classified as either ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ or ‘Should Not Be Sold’.35 The canteen manager at each intervention school will receive a tailored feedback report summarising the results of an assessment of their online canteen menu against the ‘NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy: Food and Drink Criteria’, conducted by a trained dietitian. The report will contain a copy of their online menu with all items classified as ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ or ‘Should Not Be Sold’ and graphical feedback comparing their menu to the recommendations of the criteria (ie, ‘Everyday’ foods should compromise at least 75% of the menu, and ‘Should Not Be Sold’ foods should be removed from the menu). The report will also contain suggestions for how to better align their menu with the Food and Drink Criteria, ways of increasing the proportion of ‘Everyday’ items and suggestions for alternatives to menu items classified as ‘Should Not Be Sold’.

Pricing

Price is a key driver of child and adult consumer choice.36 However, typically the prices of Australian canteen foods do not encourage healthy purchasing, with the average price of healthier items exceeding less healthy items.37 While the pricing of menu items will be at the discretion of each participating school, canteen managers will receive pricing feedback in their tailored feedback report. Specifically, a bar graph will display the average prices of ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ and ‘Should Not Be Sold’ foods and drinks within the following menu categories; main meals, snacks and drinks. This section will contain general advice to price ‘Everyday’ foods and drinks more competitively, while providing additional advice on ways to maintain canteen profitability (eg, ‘Consider applying a larger mark up for ‘Occasional’ and ‘Should Not Be Sold’ foods than for ‘Everyday’ items’).

Menu labelling

Labels

Coloured symbols will be visible at the point-of-purchase (see figure 2).38 One symbol will be placed next to every food or drink item on the online menu. Labels, symbols and colours will be assigned according to the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy34 currently implemented in NSW primary schools. Food and drink items will be categorised as either (a) ‘Everyday’, (b) ‘Occasional’ or (c) ‘Caution—consider switching’ and be labelled with green dots, grey dots or red exclamation marks, respectively. The terminology of the Healthy School Canteen Strategy has been designed for use by canteen managers, rather than parents and/or children. As such, it was determined through expert consultation that ‘Should Not Be Sold’ was an inappropriate and potentially confusing label for consumers, and ‘Caution—consider switching’ provided a behavioural action which would be more appropriate. Previous research has found simplified traffic light labelling similar to the one used in this study is highly likely to be noticed by parents when making purchase decisions for their children, with 96% of parents assigned to a traffic-light labelling menu condition reporting noticing the labelling system.39

Figure 2.

Screenshots from the Online Canteen Ordering System showing (A) menu labelling strategy and placement strategy (‘Everyday’ first,‘Caution’ middle, ‘Occasional’ last); (B) prompting—‘Add ons’ for ‘Occasional’ or ‘Caution’ hot food items; (C) Feedback—pie chart displaying the proportion of ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ and ‘Caution—consider switching’ items contained within the lunch order.

Key to labels

Once a user selects a food category from the menu (eg, sandwiches), a key explaining the labelling symbols will appear at the top of the page. The key contains the following text: (everyday) ‘Everyday - Choose everyday for Happy Healthy Kids’; (occasional) ‘Occasional—choose occasionally’; ‘Caution—Consider switching’ (see figure 2).

Placement

Menu category

Menu items will be arranged to place healthy food items and healthy food categories in positions of greatest prominence.14 Consistent with the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy, the following categories are considered to be healthier and will be positioned first within the menu: fresh fruit, sandwiches/rolls/wraps/toasties and salads. The following categories are considered to be less healthy and will be positioned lower on the menu: hot food, daily specials, meal deals, frozen ice snacks, snacks, drinks, sauces.

Menu item

Within each menu category ‘Everyday’ items will be positioned first and ‘Occasional’ items will be positioned last, with ‘Should Not Be Sold’ and unclassified items located in the middle (see figure 2). Research suggests that items at the beginning and end of each product category are purchased twice as frequently as items in the middle.14

Accessibility (proximity)

Where a menu contains multiple flavours of an ‘Occasional’ or ‘Should Not Be Sold’ item, such as multiple flavours of potato crisps, users will be required to ‘click’ through to a different screen in order to see the full list of flavours. In contrast, all flavours of ‘Everyday’ items will be listed in the main interface. Similar strategies have been shown to encourage the purchase of more accessible menu items from printed menus.40

Prompting

‘Add-ons’

If a user selects a main meal ‘Occasional’ or ‘Should Not Be Sold’ item from the Hot Food category, a pop-up message will appear prompting them to select a healthy drink and/or healthy snack option called ‘meal deal add-ons’ (see figure 2).40 The exact items included in ‘meal deal add-ons’ will depend on each school’s menu but will typically include a bottle of water and a fresh fruit and/or vegetable snack. This will be accompanied by text encouraging the purchase of ‘Everyday’ items—‘Try adding some ‘Everyday’ items for a balanced meal’. Due to programming constraints, this will apply only to hot food items that are typically sold as a single item (eg, hot dog, meat pie, chicken burger), rather than as multiple items (eg, chicken nuggets).

Text prompts

A different text prompt encouraging the selection of healthy items will appear each week in the ordering system.41 These will include: ‘Everyday’ lunches=better focus; How balanced is your lunch? Add an ‘Everyday’ item; ‘Everyday’ foods help make balanced lunches; Discover new ‘Everyday’ tastes and flavours; Browse our ‘everyday’ foods & try something new!; ‘Everyday’ foods – Fresh, Flavoursome, Fun!; Choose ‘Everyday’ items for happy, healthy kids; Hungry? ‘Everyday’ foods are good tummy fillers!; ‘Everyday’ foods are great for you!; Order all ‘Everyday’ foods & earn a lunch bag buddy; Have you tried a new ‘Everyday’ snack this week? These prompts will appear at the top of the menu and will be rotated each week according to a pre-determined schedule.

Categories

All healthy food categories will be labelled with appealing names and prompts42 (‘This is a good choice’), and be accompanied by a coloured image of the item. Less healthy categories (see ‘Menu Category’ above) will not be accompanied by any image or prompt.

Feedback

Prior to each lunch order being confirmed and submitted for payment, the user will receive graphical feedback43 in the form of a pie chart, displaying the proportion of ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ and ‘Caution—consider switching’ items contained within the lunch order (see figure 2).16 Users will have the option of amending their order at this point. The graph is dynamic, so if menu items are removed from the order, the graph will change to reflect the updated selection. In addition, a tailored message will appear under the chart, providing feedback on the lunch order. The content of the tailored message will be based on the proportion of ‘Everyday’ items within the lunch order:

100% Everyday: ‘Excellent Choice! You have earnt a lunch bag buddy!’

50%–99% Everyday: ‘Nice Choice—select all ‘Everyday’ items for a lunch bag buddy.’

1%–49% Everyday: ‘Good start—add some more ‘Everyday’ items for a more balanced meal.’

0% Everyday: ‘Try adding some ‘Everyday’ items for a more balanced meal.’

Incentives

Lunch orders that contain 100% ‘Everyday’ items will have a reward symbol printed on the label that is stuck on the paper bag in which the ordered items are delivered to the student.17 The reward symbols will automatically be printed on the student’s label by the online system. Tangible non-food rewards, such as stickers have been shown to increase children’s liking and consumption of healthy food.44 Reward symbols will rotate every week within the school term. They will contain cartoon fruit and vegetable characters and will contain the text ‘Congratulations—Healthy Lunch!’

Where possible, strategies will be automated by the provider, that is, automatically applied once the menus items are entered into the online system as ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ or ‘Caution’. Otherwise, strategies will be manually applied by accessing the canteen manager portal within the online canteen system and manually altering the presentation of menu items.

Control

Schools allocated to the control group will only have access to the standard online canteen system without any of the above strategies.

Fidelity check

Once per term following the implementation of the intervention, a research assistant will check each school’s online menu to ensure that any new items are correctly classified and the intervention strategies are applied accordingly. If there is insufficient information on the online menu to classify the new items according to the Healthy School Canteen Strategy, a research assistant will call the canteen manager to collect brand, portion or recipe information as needed. The research assistant will also ask whether any portion sizes, ingredients or brands have changed. The intervention strategies will then be applied to the new items.

The only strategy we cannot verify via online is the incentives and these will be verified via visit.

Public involvement

The public were not involved in the development of the research questions, the study design or recruitment to the trial.

Data collection measures and procedures

Primary outcomes

The primary trial outcomes are the mean energy (kilojoules), saturated fat (grams), sugar (grams) and sodium (milligrams) content of online canteen lunch order purchases for each student within the defined baseline and follow-up data collection periods. The primary trial end-point is approximately 12 months post-baseline. This is to enable baseline and follow-up data collection to occur within the same term, 1 year apart. The intervention will still be operational during follow-up data collection for the intervention group. Assessment of primary trial outcomes will be based on lunch order purchase data from the cohort of students who place an order during the baseline period. Data from the pilot trial indicated that 82%–91% of students for whom a lunch is ordered during one term will also order lunch during a subsequent term.26

Menu assessment process

Trained research assistants with Nutrition and Dietetics qualifications will conduct a menu assessment for each participating school and will classify each menu item as ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ or ‘Caution’ and will record the nutrition information for each product. Where additional information is required beyond what is listed on the canteen menu, the school canteen manager will be phoned to collect brand and product name and serve size or recipe, including yield. For commercial (eg, packaged products) and assembled (eg, sandwiches) items research assistants will use a database of commonly stocked canteen products to obtain the nutrition information panel. The canteen product database was established in 2015 and was generated based on data collected from 38 schools and includes over 2000 commonly stocked canteen items. It was used as the basis for nutritional information classification in the pilot study25 and has been regularly updated. The canteen product database contains the nutrient panel information for all items which includes the brand, serve size and energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium content per serve and per 100 g. If the item is not listed in the canteen product database, two additional sources will be searched: (1) The FoodFinder Database—a list of common canteen foods classified under the NSW Healthy Canteen Strategy supplied by the NSW Ministry of Health,45 and (2) The FoodSwitch website—a list of supermarket products maintained by the George Institute for Global Health.46 If the item cannot be located in any database, the research assistant will search for the nutrient panel online, and if it cannot be located, a ‘generic’ nutrient profile will be assigned using a commercial equivalent found in the canteen product database. For canteen-made items (eg, muffins) the recipe will be entered into nutrition analysis software (FoodWorks V.9)47 to obtain the nutrient profile. FoodWorks is a commercially available software program that contains the latest and most comprehensive Australian and New Zealand food data and is the industry standard in nutritional analysis software for dietitians and researchers.47 A quality assurance process will be adopted as part of the menu assessments, whereby one dietitian will conduct the assessment and a second dietitian will confirm each item classification. Any discrepancies will be resolved between the two dietitians, and if needed a third dietitian will be consulted to settle the discrepancy. The proposed process is consistent with menu assessment procedures used in a number of previous studies conducted by the research team.26 48 49

Lunch order purchasing data

The purchasing data that is automatically collected by the online canteen system during the baseline and follow-up period will be supplied to the researchers by the provider in a de-identified format. One full school term (10 weeks) of purchasing data will be provided at each time point for analysis. Each menu item in the online canteen system is assigned a unique product ID code. This ID code will be matched to the product’s nutritional profile determined in the menu assessment process outlined above, allowing for the calculation of the mean energy (kilojoules), saturated fat (grams), sugar (grams) and sodium (milligrams) content of online canteen lunch order purchases for each student. For each school, a second research assistant will perform a quality assurance check of approximately 10% of the canteen menu items, to ensure that the nutrition profile has been correctly matched to the purchasing data. Special event orders (eg, end of term pizza lunch) will be excluded from analysis, given canteen managers typically create a new menu for these events which may not have the intervention strategies applied. Similarly, recurring orders (ie, orders placed ahead of time to be repeated regularly without the need for the user to subsequently engage with the online canteen system) will be excluded from analysis as the user may not have been exposed to the intervention strategies.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse outcome: change in canteen revenue

In order to determine whether the intervention has any adverse impact on school canteen revenue, the mean weekly canteen revenue from online orders at baseline and follow-up will be compared between intervention and control groups. Revenue data automatically collected by the online system will be supplied to the research team by the provider.

Nutritional quality

The overall nutritional quality of lunch order purchases during the baseline and follow-up periods will be compared between groups by calculating the (1) total proportion of (i) ‘Everyday’ items, (ii) ‘Occasional’ items and (iii) ‘Should Not Be Sold’ items and (2) the mean per cent of energy from (i) sugar and (ii) saturated fat that are purchased per student over each data collection period. Trained research assistants with Nutrition and Dietetics qualifications and blinded to group allocation will classify each menu item based on the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy: Food and Drink Criteria.35

Intervention effect over time

To explore the trajectory of the intervention effect over the course of the intervention period, time-series analysis will be conducted. The semi-continuous data collection will allow for such trends to be explored across all study sites. The functional form of the trajectory will be explored once data is collected.

Intervention cost, cost consequence and cost-effectiveness

A trial-based economic evaluation involving costing, cost-consequence analysis and, subject to assessment of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness analysis, will be undertaken. Cost data will be collected using a specifically designed template, supported by detailed project management records.

Process measures

The following process measures will be collected to determine any changes in availability and price of menu items, as well as intervention acceptability.

Change in availability

At baseline and follow-up, an experienced dietitian will use the assessment of nutrition quality (above) to calculate the proportion of ‘Everyday’ items, ‘Occasional’ items and ‘Should Not Be Sold’ items within each menu, to compare against the ‘NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy: Food and Drink Criteria’ which state that at least 75% of the menu should be ‘Everyday’ items and no more than 25% should be ‘Occasional’ items. The proportion of schools meeting the criteria at baseline and follow-up will be reported per group to determine if changes to the availability of healthier items were made.

Change in pricing

At baseline and follow-up, a research assistant will calculate the average price of ‘Everyday’, ‘Occasional’ and ‘Should Not Be Sold’ items to determine if changes to the price levels of items were made.

Intervention acceptability

Intervention acceptability will be assessed using a series of questions about functionality and useability using Likert scales (strongly agree to strongly disagree). This data will be collected from all canteen managers at intervention schools as part of the canteen manager survey administered at follow-up.

Additional support received

Given the NSW Healthy School Canteen Strategy was launched in 2017,34 and that NSW Local Health Districts are mandated to support schools within their boundaries to submit their canteen menu for assessment against the new criteria,50 measurement of the receipt and timing of such additional support will be assessed at follow-up via a canteen manager survey. Given the random assignment of school to intervention and control groups, it is anticipated that this support will be evenly distributed across the sample.

Other data

Student grade (kindergarten to grade 5) will be automatically collected by the online canteen system. School level data including size (number of enrolments) and sector, grades enrolled (eg, kindergarten to grade 6) and percent of students who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander will be collected from the ‘My School’ website.51 School Socio-Economic Index52 and school location (metropolitan, provincial, remote and very remote)53 will be calculated based on school postcode, taken from the ‘My School’ website.51 Data regarding canteen operations (eg, number of days open, model of operation, paid canteen manager) will be collected during the canteen manager survey at follow-up. Analytics data that are automatically collected by the online canteen system (eg, frequency of use, time taken to place the order) will be supplied by the provider.

Data quality and integrity

The purchasing data that are automatically collected by the online canteen system and used in the assessment of trial outcomes will undergo independent verification by the research team to ensure its integrity. Specifically, in a random sample of approximately 20% of participating schools, research assistants will visit the school canteen for 1 day and will record: all items ordered through the online canteen system; all items provided to students in the lunch order bags; all product substitutions made by the canteen manager prior to foodservice (ie, products that have been ordered for students, but are out of stock on the day and are replaced with a similar item); and the presence of any printed reward symbols on student lunch labels. This information will be collected from the lunch order labels, as generated by the online system, verified against the contents of each student lunch order (ie, the contents of each made up lunch bag will be checked) and cross-referenced with the purchasing data supplied by the provider.

Dissemination

Dissemination of the trial results will be in summary form only; no identifying information about schools or individual participants will be available. Dissemination of the research findings could involve peer-reviewed scientific publications, reports, presentations at national or international conferences, or part of student research theses.

Analysis

Statistical analysis

Each primary trial outcome will be assessed using a separate linear mixed model under an intention-to-treat framework. The mean nutritional content (ie, energy, saturated fat, sugar and sodium) of online lunch orders placed for an individual student will be compared between intervention and control groups at follow-up, adjusting for baseline values, and clustering within school (using a random school-level intercept). The linear mixed model will account for repeated measures of the trial outcome at the student and school level. To account for elevated type 1 error from multiple primary outcomes, a Holm-Bonferroni procedure will be used. A per protocol analysis will also be conducted to determine the effect of the intervention strategies being partially applied. Exploratory sub-group analyses will also be conducted, testing the average energy content per student lunch order for treatment group interactions by demographic characteristics (ie, student grade—infants vs primary; and school sector) and purchasing characteristics (ie, 1/+orders per week vs <1 order per week). The trial data will be reported in adherence with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 guidelines54 for reporting cluster randomised controlled trials.

Sample size calculation

As dose–response relationships exist between three of the four primary outcomes (saturated fat,55 sugar56 and sodium57) and dietary-related clinical health outcomes, the sample size calculation was based on the estimated between group differences in daily energy intake that would be required to offset unhealthy weight gain.58 It is expected that approximately 194 students at each school will place at least one online lunch order during the baseline data collection period, and that 86% of those of students will order within the follow-up data collection period, and that 70% of orders are placed using a mobile device (and will be included in the analysis). Assuming that a standard lunch order has a SD of 616 kJ, and assuming an ICC (Intraclass Correlation Coefficient) of 0.05, the participation of 26 schools (13 each arm) would enable detection of a 195 kJ difference between groups at follow-up with 80% power at the Bonferroni adjusted level of 0.0125 significance level (preserving a family-wise type 1 error rate of 5%).

Economic analysis

A trial-based economic evaluation involving costing, cost-consequence analysis and, subject to assessment of effectiveness, cost-effectiveness analysis, will be undertaken. The intervention will be compared against the control group (usual-practice) from a societal perspective. Resource use will be identified, measured and valued for the intervention development, implementation and sustainability stages. It will be assumed that control schools will incur no additional costs beyond the use of the online ordering system (ie, usual practice). Micro costing will be used to calculate the system level and school level cost associated with the intervention. An incremental cost-effectiveness ratio will be calculated as the difference in mean total cost divided by the observed difference in the primary outcome of kilojoules. Uncertainty analysis will be undertaken using non-parametric bootstrapping to derive uncertainty intervals around the key variables as well as the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. Sensitivity and scenario analysis will be undertaken to test the impact of changing key design features of the intervention and scale-up of the implementation model.

Discussion

This trial adopts a rigorous cluster randomised controlled design and tests the effectiveness of an intervention that is integrated into an existing online canteen system with wide reach throughout Australian schools. The intervention will be evaluated using routinely collected lunch order purchasing data from thousands of primary school students. The results should be considered in the context of the strengths and limitations of the research. The external validity of the findings may be limited given the application of this intervention only to primary schools from one Australian state, although the inclusion of all school types across socioeconomic strata is a strength. Furthermore, study findings may be limited due to the use of purchasing data as opposed to consumption data, and an inability to identify the person placing the order (ie, a student ordering for themselves or a parent ordering on behalf of a student). Notwithstanding these limitations, it is anticipated that the trial results will be used to inform future implementation of public health nutrition interventions through school canteens and may be transferrable to other online systems for ordering food.

Ethics and dissemination

Study information statements and consent forms are available from the authors on request. Study results will be disseminated through presentations at relevant national and international conferences and to key stakeholders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Flexischools, Alix Hall and The Research Advisory Group.

Footnotes

Contributors: RW led the development of this manuscript. RW, LW, KB, KC, JW and CR secured the funding source. RW, TD and LW developed the intervention strategies. TD, RW and LW determined the measures to be used, and JA, CO, RW and LW determined the analyses to be conducted. RW, TD, PG, KB, KC, SLY, KS, RZ, CR, JW, JA, CO, RS, NN, KR, PR and LW contributed to the research design and trial methodology, and read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by The National Health and Medical Research Council, grant number APP1120233. In-kind support is provided by Hunter New England Population Health and the Hunter Medical Research Institute. RW is supported by an NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1113377); SLY is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) DP170103979; RS is supported by a NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1150661); NN is supported by a NHMRC TRIP Fellowship (APP1132450) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship; PR is supported by a NSW Health Prevention Research Support Program (PRSP) Fellowship; LW is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (APP1128348), Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (101175) and a Hunter New England Clinical Research Fellowship. Authors RW, SLY, RS, NN, JW and LW, receive salary support from Hunter New England Population Health. The provider (Flexischools) was selected through a competitive tender process. Flexischools is a commercial organisation that provided the online canteen ordering infrastructure to schools that were included in the study. Flexischools received funds from the grant to reprogram their online canteen system to accommodate the changes required as part of the intervention.

Disclaimer: The NHMRC has not had any role in the design of the study as outlined in this protocol and will not have a role in data collection, analysis of data, interpretation of data and dissemination of findings. Flexischools had no role in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (H-2017-0402), the NSW Department of Education and Communities (SERAP) and the Catholic Education Office Dioceses of Sydney, Parramatta, Lismore, Maitland-Newcastle, Bathurst, Canberra-Goulburn, Wagga Wagga, Wollongong and Wilcannia-Forbes.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Australian burden of disease study: impact and causes of illness and death in Australia 2011 [Internet. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maynard M, Gunnell D, Emmett P, et al. . Fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants in childhood and risk of adult cancer: the Boyd Orr cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:218–25. 10.1136/jech.57.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organisation (WHO) Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Geneva: World Health Organisation (WHO), 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Department of Health and Ageing Healthy Weight 2008 Australia’s Future 2003.

- 5. Bell AC, Swinburn BA. What are the key food groups to target for preventing obesity and improving nutrition in schools? Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:258–63. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardy L, Mihrshahi S, Drayton B, et al. . NSW Schools Physical Activity and Nutrition Survey (SPANS) 2015: Full Report [Internet. Sydney: NSW Department of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finch M, Sutherland R, Harrison M, et al. . Canteen purchasing practices of year 1-6 primary school children and association with Ses and weight status. Aust N Z J Public Health 2006;30:247–51. 10.1111/j.1467-842X.2006.tb00865.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nathan N, Wolfenden L, Bell AC, et al. . Effectiveness of a multi-strategy intervention in increasing the implementation of vegetable and fruit breaks by Australian primary schools: a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2012;12:651 10.1186/1471-2458-12-651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nathan N, Wolfenden L, Butler M, et al. . Vegetable and fruit breaks in Australian primary schools: prevalence, attitudes, barriers and implementation strategies. Health Educ Res 2011;26:722–31. 10.1093/her/cyr033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfenden L, Nathan N, Williams CM, et al. . A randomised controlled trial of an intervention to increase the implementation of a healthy canteen policy in Australian primary schools: study protocol. Implementation Sci 2014;9 10.1186/s13012-014-0147-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Driessen CE, Cameron AJ, Thornton LE, et al. . Effect of changes to the school food environment on eating behaviours and/or body weight in children: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2014;15:968–82. 10.1111/obr.12224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woods J, Bressan A, Langelaan C, et al. . Australian school canteens: menu guideline adherence or avoidance? Health Promot J Austr 2014;25:110–5. 10.1071/HE14009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thorndike AN, Riis J, Sonnenberg LM, et al. . Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: promoting healthy food choices. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:143–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dayan E, Bar-Hillel M. Nudge to nobesity II: menu positions influence food orders. Judgm Decis Mak 2011;6:333–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwartz MB. The influence of a verbal prompt on school lunch fruit consumption: a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2007;5:4–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brug J, Campbell M, van Assema P. The application and impact of computer-generated personalized nutrition education: a review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns 1999;36:145–56. 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00131-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Just D, Price J, options D. Default options, incentives and food choices: evidence from elementary-school children. Public Health Nutr 2013;16:2281–8. 10.1017/S1368980013001468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Results from the school health policies and practices study 2014. Atlanta, GA: U.S: Department of Health and Human Services, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yoong SL, Nathan NK, Wyse RJ, et al. . Assessment of the school nutrition environment: a study in Australian primary school canteens. Am J Prev Med 2015;49:215–22. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wyse R, Yoong SL, Dodds P, et al. . Online canteens: awareness, use, barriers to use, and the acceptability of potential online strategies to improve public health nutrition in primary schools. Health Promot J Austr 2017;28:67–71. 10.1071/HE15095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delaney T, Wolfenden L, Yoong SL, et al. . A cluster randomized controlled trial of a consumer behavior intervention to improve healthy food Purchases from online canteens. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2018;14:13–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Norman GJ, Zabinski MF, Adams MA, et al. . A review of eHealth interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:336–45. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fast Company & Inc The hidden psychology of ordering food online 2016.

- 24. Department of Health and Ageing National Healthy School Canteens Evaluation Toolkit [Internet], 2018. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/5FFB6A30ECEE9321CA257BF0001DAB17/$File/Evaluation%20Toolkit.pdf

- 25. Delaney T, Wyse R, Yoong SL, et al. . Cluster randomised controlled trial of a consumer behaviour intervention to improve healthy food purchases from online canteens: study protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014569 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Delaney T, Wyse R, Yoong SL, et al. . Cluster randomized controlled trial of a consumer behavior intervention to improve healthy food purchases from online canteens. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:ajcn158329–20. 10.3945/ajcn.117.158329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Flexischools Flexischools [Internet], 2013. Available: https://www.flexischools.com.au/

- 28. Hills A, Nathan N, Robinson K, et al. . Improvement in primary school adherence to the NSW healthy school canteen strategy in 2007 and 2010. Health Promot J Austr 2015;26:89–92. 10.1071/HE14098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, et al. . Altering micro-environments to change population health behaviour: towards an evidence base for choice architecture interventions. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1218 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Swinburn B, Egger G, Raza F. Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 1999;29:563–70. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wyse R, Delaney T, Nathan N. eLunch? Will parents use online canteens to purchase their child’s lunch? Poster presented at: Australian & New Zealand Obesity Society 2015 Annual Scientific Meeting, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wellard L, Chapman K, Wolfenden L, et al. . Who is responsible for selecting children's fast food meals, and what impact does this have on energy content of the selected meals? Nutrition & Dietetics 2014;71:172–7. 10.1111/1747-0080.12106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Glanz K, Bader MDM, Iyer S. Retail grocery store marketing strategies and obesity: an integrative review. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:503–12. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. NSW Department of Education Healthy School Canteens: Summary of Evidence to inform a Revised Strategy [Internet], 2016. Available: https://healthyschoolcanteens.nsw.gov.au/about-the-strategy/the-revised-strategy [Accessed 21 May 2018].

- 35. NSW Ministry of Health The NSW healthy school canteen strategy: food and drink criteria. 3th edn Sydney, NSW: NSW Ministry of Health, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36. French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M, et al. . Pricing and promotion effects on low-fat vending snack purchases: the chips study. Am J Public Health 2001;91:112-7 10.2105/ajph.91.1.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Billich N, Adderley M, Ford L, et al. . The relative price of healthy and less healthy foods available in Australian school canteens. Health Promot Int 2018;104 10.1093/heapro/day025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tandon PS, Wright J, Zhou C, et al. . Nutrition menu labeling may lead to lower-calorie restaurant meal choices for children. Pediatrics 2010;125:244–8. 10.1542/peds.2009-1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dodds P, Wolfenden L, Chapman K, et al. . The effect of energy and traffic light labelling on parent and child fast food selection: a randomised controlled trial. Appetite 2014;73:23–30. 10.1016/j.appet.2013.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Downs JS, Loewenstein G, Wisdom J. Strategies for promoting healthier food choices. Am Econ Rev 2009;99:159–64. 10.1257/aer.99.2.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delaney C, Martin-Biggers JT, Povis-Alleman G, et al. . Nudges: fun, motivational messages to encourage and Reassure parents in the HomeStyles randomized controlled trial. Faseb J 2016;30:896–15. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Piqueras-Fiszman B, Spence C. Sensory expectations based on product-extrinsic food cues: an interdisciplinary review of the empirical evidence and theoretical accounts. Food Qual Prefer 2015;40:165–79. 10.1016/j.foodqual.2014.09.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Brennan-Martinez C, et al. . Using animated computer-generated text and graphics to depict the risks and benefits of medical treatment. Am J Med 2012;125:1103–10. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.04.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cooke LJ, Chambers LC, Añez EV, et al. . Eating for Pleasure or profit: the effect of incentives on children's enjoyment of vegetables. Psychol Sci 2011;22:190–6. 10.1177/0956797610394662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. NSW Government FoodFinder [Internet]. Healthy Food Finder. Available: https://www.foodfinder.health.nsw.gov.au

- 46. The George Institute for Global Health FoodSwitch [Internet]. Foodswitch. Available: https://www.foodswitch.com.au/

- 47. Xyris Software Food Works [Internet]. FoodWorks 9 Professional, 2018. Available: https://xyris.com.au/products/foodworks-9-professional/ [Accessed 12 Sep 2018].

- 48. Wolfenden L, Nathan N, Janssen LM, et al. . Multi-strategic intervention to enhance implementation of healthy canteen policy: a randomised controlled trial. Implementation Sci 2017;12 10.1186/s13012-016-0537-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams CM, Nathan N, Delaney T, et al. . CAFÉ: a multicomponent audit and feedback intervention to improve implementation of healthy food policy in primary school canteens: protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006969 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. NSW Department of Education. Healthy School Canteens - More Support [Internet], 2018. Available: https://healthyschoolcanteens.nsw.gov.au/canteen-managers/resource-centre/more-support [Accessed cited 2018 Nov 15].

- 51. Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. My School [Internet]. Available: https://www.myschool.edu.au/

- 52. Australian Bureau of Statistics Technical paper: socio-economic indexes for areas. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Australian Bureau of Statistics The Australian Standard Geographical Standard (ASGS) Remoteness Structure [Internet], 2014. Available: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/remoteness+structure

- 54. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . Consort 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012;10:28–55. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schwab U, Lauritzen L, Tholstrup T, et al. . Effect of the amount and type of dietary fat on cardiometabolic risk factors and risk of developing type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer: a systematic review. Food Nutr Res 2014;58. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v58.25145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Basu S, Yoffe P, Hills N, et al. . The relationship of sugar to population-level diabetes prevalence: an econometric analysis of repeated cross-sectional data. PLoS One 2013;8:e57873 10.1371/journal.pone.0057873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. FJ H, Li J, MacGregor GA. Effect of longer term modest salt reduction on blood pressure: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ 2013;346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang YC, Orleans CT, Gortmaker SL. Reaching the healthy people goals for reducing childhood obesity: closing the energy gap. Am J Prev Med 2012;42:437–44. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.