Abstract

A 67-year-old woman presented in 2012 with a crusty nodule on the left lower limb. Histopathological examination at this time reported a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Two years later, she underwent lymphadenectomy and radiotherapy due to unilateral inguinal and pelvic sidewall nodal metastases. The following year she required excision of two subcutaneous lesions, reported pathologically to be SCC metastases. Further imaging following cyberknife radiotherapy to new brain metastases demonstrated widespread metastatic visceral disease. Twelve cycles of carboplatin and capecitabine failed to halt disease progression. In February 2017, she commenced pembrolizumab, achieving an excellent response and currently has no clinical or radiological evidence of disease. Given the unusual behaviour of her cancer, a histopathological review was requested. The diagnosis was revised to that of porocarcinoma (PC). This represents the first documented case of PC treated with immunotherapy. As of March 2019, the patient remains free of disease.

Keywords: dermatology, skin cancer, therapeutic indications

Background

This is an important case as it represents the first documented incidence of porocarcinoma (PC) treated with immunotherapy, and most interestingly, describes a patient achieving and sustaining a complete response with this novel treatment approach.

PC is a rare adnexal malignancy that accounts for an estimated 0.005%–0.01% of epidermal skin neoplasms.1 2 It is believed to arise from the acrosyringium of the sweat gland of the skin. The aetiology of PC is poorly understood and very little guidance is available in the literature on protocols for treatment and follow-up. Chemotherapy±radiotherapy are the standard treatments for metastatic disease, but no data strongly support any particular regimen.

This case describes a patient with PC misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), reminding us to question and revisit the original diagnosis when a disease follows a highly unusual clinical course. This patient achieved a complete response following progressive disease on doublet chemotherapy.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old woman presented in 2012 with a crusty nodule on the left lower leg. Her medical history was significant only for a breast cancer in 1995, for which she underwent a lumpectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy, and surgery for a bladder prolapse in 2002. She had evidence of extensive sun damage, but no previous dermatological issues. She took no regular medications, and had a family history significant only for a grandmother with breast cancer. She was a retired teacher with one son, had never smoked and consumed alcohol only rarely.

Histopathological examination of this nodule reported a poorly differentiated SCC. She presented 2 years later with bulky lymph node metastases in the left groin, pelvic sidewall and lower left retroperitoneum. She underwent a lymphadenectomy, which demonstrated pathologically 1 of 14 dissected inguinal nodes to be positive for metastases, reported as consistent with poorly differentiated SCC. Similarly, one of five pelvic sidewall nodes was involved. Following surgery, she received radiotherapy to the affected basin. In 2015, she then represented between follow-ups with two subcutaneous lesions on the right thigh. These were reported as poorly differentiated SCC metastases. She underwent excision of the two lesions but presented shortly afterwards with brain metastases and was treated with cyberknife radiosurgery.

On follow-up MRI of the head and CT scan of the body, she was found to have widespread metastatic disease in major organs, and subcutaneous lesions continued to appear all over the body. She was then treated with 12 cycles of carboplatin and capecitabine but the disease continued to progress. In February 2017, she was offered immunotherapy and commenced single agent pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg intravenously, delivered on a 3-weekly schedule. By week 12, she had achieved an excellent partial response, and by May 2018, there was no clinical or radiological evidence of disease. Over 22 months later, she continues on this treatment.

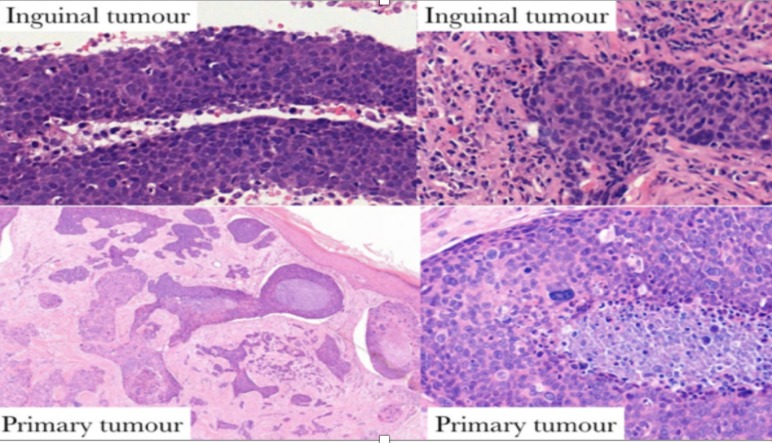

Given the unusual behaviour of her presumed SCC, a review of the original histopathology and subsequent nodal dissections was requested. This review revised the diagnosis to that of PC, a rare and sometimes aggressive skin malignancy. Histopathologically, this tumour was formed of variably sized islands of cells, infiltrating cords and trabeculae, some with retraction artefact. There was a comedo necrosis. The constituent cells included basaloid epithelioid cells, more eosinophilic epithelioid cells and bizarre pleomorphic forms. The overlying and adjacent epidermis had multiple foci of involvement, including pagetoid spread (figure 1). Despite the absence of convincing ducts, the morphology of the tumour was that of a PC. No perineural or vascular invasion was identified.

Figure 1.

Histopathology of the primary cutaneous tumour, which is composed of infiltrating cords and trabeculae of basaloid cells, some with retraction artefact. Comedo necrosis and multiple foci of epidermal involvement, including pagetoid spread. These features are characteristic of porocarcinoma.

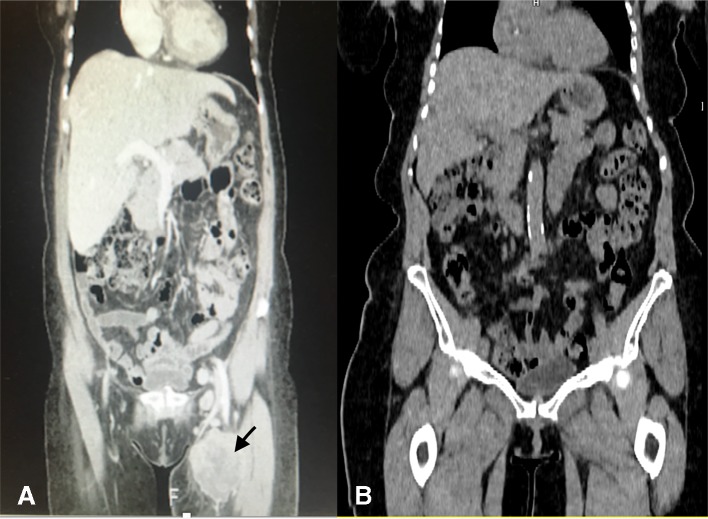

On presentation with left inguinal lymph node abnormalities, CT scanning confirmed features consistent with bulky left groin, left pelvic sidewall and left peritoneal metastases (figure 2A), and this leads to lymphadenectomy.

Figure 2.

CT imaging demonstrates bulky lymph nodes metastases in the left groin, pelvic sidewall and lower left retroperitoneum preimmunotherapy and postimmunotherapy.

Histopathologically, the resected lymph node metastases were also initially reported as consistent with poorly differentiated SCC. Figure 3 displays fragments of tumour with considerable admixed inflammation and multiple foci of necrosis. There are multiple strips of cohesive atypical basaloid epithelial cells, which do not have identifiable keratinisation or intercellular prickles (figure 3A–C); duct formation is not present. A separate component of the tumour consists of markedly malignant pleomorphic cells. Immunohistochemistry (figure 3D, AE1/AE3) confirmed the epithelial lineage but was otherwise unremarkable.

Figure 3.

(A–D) Histopathology of resected lymph node displays multiple strips of cohesive atypical basaloid epithelial cells. Immunohistochemistry confirms the epithelial lineage (D).

A comparison of these portions of the tumour with the cutaneous PC indicated many similarities between the epithelial strips and portions of the primary carcinoma (figure 4); PC typically has such basaloid cords/trabeculae and, in the context of the revised primary diagnosis and tumour morphology, the inguinal disease was considered to be a PC metastasis.

Figure 4.

Histopathological comparison between primary tumour and lymph node metastasis indicates much morphological similarity between the epithelial strips within the lymph node and portions of the primary carcinoma.

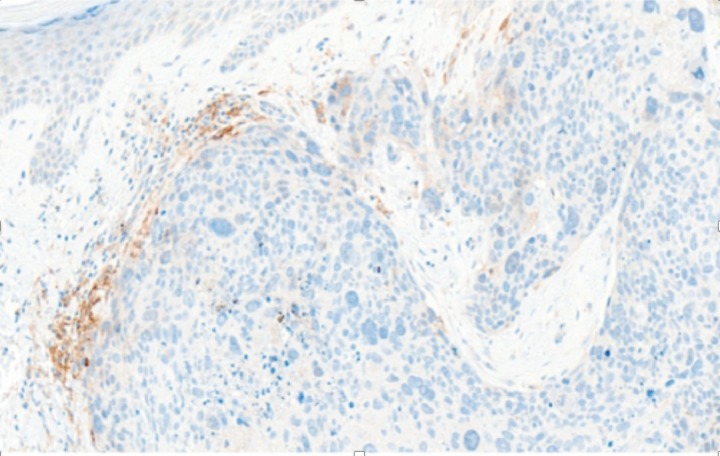

Immunohistochemistry for programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) demonstrates numerous foci of positivity in the inflammatory cell infiltrate, and several weak foci of tumour expression (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemistry for PD-L1 demonstrates numerous foci of positivity in the inflammatory cell infiltrate, and several weak foci of tumour expression. PD-L1, programmed cell death ligand-1.

A number of short months following lymphadenectomy, the patient presented with slurring of her speech, blurring of her vision and a significant deterioration in her coordination. MRI of the brain revealed intracranial metastases.

Following treatment with cyberknife, a CT of her thorax, abdomen and pelvis (TAP) revealed diffuse visceral disease. Following eight cycles of capecitabine and carboplatin, restaging imaging demonstrated progression of visceral disease. During this period on chemotherapy, she had multiple cutaneous lesions excised, all reported histologically to be SCC.

She commenced pembrolizumab in February 2017, and a CT TAP in May 2017 demonstrated a complete radiological response which has been sustained to the time of a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan in March 2019 (figure 2B).

Differential diagnosis

Pathological differential diagnoses for PC include SCC and basal cell carcinomas (BCC), amelanotic melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, clear cell hidradenocarcinoma and skin metastases from other primary sources and tumours that can display pagetoid epidermotropism, including Paget’s and Bowen’s disease.

Outcome and follow-up

As of March 2019, the patient remains in complete radiological and clinical remission following 20 months of treatment with pembrolizumab. For her first year following pembrolizumab treatment, she has been scanned 3 monthly. This will be extended to 6 monthly for a further 4 years if she remains disease free.

Discussion

Since the first description of PC by Pinkus and Mehregan, approximately 500 cases have been documented in the literature.3 A recent UK study demonstrated a rapid rise in PC incidence in the East of England,4 and using age-standardised incidence rates, estimated a rapidly increasing number of cases likely to be diagnosed over the next decade. It is possible that this trend reflects greater diagnostic awareness of the tumour morphology.

As PC is so rare, epidemiological data vary widely across small case series. A recently published meta-analysis of 453 patients reported 49% of cases were male, and 51% were female.4 The mean age was 67.5 years old, with most patients diagnosed in their seventh and eighth decades. The most common anatomical sites were the head and neck (39.9%), followed by lower extremity (33.9%).4 Risk factors include exposure of the affected area to trauma, burning or radiotherapy, immunosuppressive drugs especially after organ transplantation, prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light and AIDS.4 Some patients have a long history of a poroma prior to evolution to the malignant variant.4

Early published case series suggested that PC was a highly aggressive malignant entity, with approximately two-thirds of patients developing local recurrence or metastatic disease. Larger case series followed, and did not support such an aggressive natural history.1 5 6 Nevertheless, the propensity for metastasis is considerably higher than for cutaneous SCC. The largest case series to date (69 patients) reported adverse event rates of 17% for local recurrence, 19% for nodal metastasis and 11% for distant metastases or death.7 Epidermotropic spread is an uncommon but characteristic feature.

SCC, however, is the second most common skin cancer after BCC.8 The lifetime risk for developing SCC is believed to be 7%–11%, and this has been increasing in the last several decades.9 While less likely to metastasise than PC, SCC is generally more aggressive than BCC. The mortality rate from cutaneous SCC is difficult to estimate, mostly due to inadequate incidence data. An Australian study estimated case fatality to be 4%–5%, whereas US studies suggest a 1% rate.10 11 Over 90% of patients with SCC are cured with local therapies,12 but the remainder will require additional treatment.

Robson et al suggest in their retrospective 69 patient PC case series that a more aggressive clinical course may be indicated by more than 14 mitoses per ten high power fields (HR for death 17.0, 95% CI 2.71 to 107), lymphovascular invasion by tumour (HR 4.41, 95% CI 1.13 to 17.2) and depth >7 mm (HR 5.49, 95% CI 1.0 to 30.3).7 Thus, mitoses, lymphovascular invasion and tumour depth should be evaluated in these tumours. The primary tumour of our patient measured only 3.6 mm, lacked convincing lymphovascular invasion but 22.5 mitoses were counted per square mm indicating a very high proliferative fraction.

Wide local resection of PC is the main line of treatment for localised tumours and cure rates have been reported to be around 70%–80%.13 Successful treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery has also been reported.14 There is no consensus concerning its surgical management. Belin et al conducted a retrospective analysis of 24 patients in order to identify prognostic histopathogical factors that could guide the surgical procedure.15 They classified biopsy samples into three subtypes: infiltrative, pushing and pagetoid. They proposed an algorithm: excisional biopsy of the primary PC and identification of the subtype, then, no additional surgery for pushing PC, while excision with additional Mohs micrographic surgery for the infiltrative and pagetoid subtypes.15 Non-surgical forms of treatment, such as electrochemotherapy and intralesional photodynamic therapy, are also described in the literature.16 17

Lymphadenectomy is necessary in cases of node positive disease, poorly differentiated tumour and in the case of local recurrence of previously resected primary disease.18 Reports suggest radiosensitivity of these tumours and recommend adjuvant radiation in high-risk cases, that is, large tumours >5 cm, positive surgical margins and moderate to poorly differentiated tumours with lymphovascular invasion,19 but is not yet standard of care. Fujimura et al describe a successful treatment of PC cervical lymph nodal metastases with cyberknife radiosurgery.20

There has been little evidence for a specific chemotherapy-based regimen in metastatic PC due to the rarity of this cancer. PC has proven relatively resistant to many cytotoxic agents,21 with some exceptions—Plunkett et al have observed a clinical and radiological response to chemotherapy in a 45-year-old female renal transplant patient with metastatic PC.21 Examples of chemotherapeutic agents that have been used in combination therapy are: doxorubicin, mitomycin, vincristine and 5-fluorouracil; anthracycline, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and bleomycin; isotretinoin and interferon-alpha; carboplatin and paclitaxel; cisplatin and docetaxel; paclitaxel and interferon-alpha18. Some groups have used targeted therapy in a subset of metastatic PC, in particular, cetuximab and bortezomib in combination with chemotherapy.22 23

Pembrolizumab is a humanised antibody targeting the PD-1 of lymphocytes, and is frequently used to treat cancers with a high mutational burden such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, head and neck cancer. In 2017, the Food and Drug Administration granted pembrolizumab accelerated approval for use in any unresectable or metastatic solid tumour with DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiencies or a microsatellite instability-high (MSI) state. There is some published evidence that suggests it may be of limited benefit in advanced SCC.24–26

There are no documented reports of immunotherapy agents being used in patients with PC, and indeed, it was tried as a second-line therapy in our patient when she was believed to have a rapidly progressive SCC. The patient’s complete and sustained response to pembrolizumab is unexpected, and further research in this area is needed. However, it is likely that pembrolizumab’s mechanism of action in this instance is the same as it would be for any PDL-1 expressing tumour: pembrolizumab binds to the PD-1 receptor, blocking both immune-suppressing ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2, from interacting with PD-1 to help restore T-cell response and immune response. Retrospective immunohistochemical evaluation of the primary tumour in our patient indicated focal expression of PD-L1 in both the tumour and adjacent inflammatory cells (figure 5). We suggest multidisciplinary discussion and immune assessment of the tumour for PD-L1 expression, and potentially for MMR and MSI, where available, and possible consideration of an immunotherapy agent, if felt to be of potential benefit.

Patient’s perspective.

Since 2012 my journey with cancer has been quite traumatic. I had a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and having dealt with several operations to remove tumours, subsequent radiotherapy and cyberknife treatment for brain tumours, 12 cycles of chemotherapy failed to control the stage 4 cancer from spreading to my major organs. I was in a desperate situation. It was recommended that I was suitable for immunotherapy. After nearly two years of this treatment the response has been amazing and I am now in remission. A dermatologist was curious about my case history. A histopathology review was requested and porocarcinoma was diagnosed, a very rare skin cancer. Immunotherapy had never been used to treat this cancer and I am the very first person to prove its success. I am extremely grateful for the very experienced team treating me. Also, if it were not for the inspirational and dedicated scientists who have pioneered immunotherapy, I would not be alive today.

Learning points.

Porocarcinoma (PC) is a rare cutaneous malignancy that most commonly presents in the seventh and eighth decades, and is most often found on the head and neck and lower limbs.

PC can be difficult to distinguish from squamous cell carcinoma pathologically, but given the significantly greater propensity of PC to metastasise, the characteristic features of PC are emphasised.

Consideration should be given to histopathological review of any primary diagnosis if the disease subsequently follows a highly unusual clinical course.

Little guidance is available in the literature regarding treatment and follow-up protocols for PC.

Immunotherapy is not an approved treatment for patients with metastatic PC, but may be worth considering in patients with metastatic and progressing disease, and consideration could be given to testing these tumours for PD-L1 expression, and potentially, for microsatellite instability and mismatch repair status.

Footnotes

Contributors: KAL prepared the manuscript and edited all drafts. MC contributed to the manuscript. VB was the treating dermatologist and contributed to the manuscript. AR reviewed the histopathology and contributed to the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Mehregan AH, Hashimoto K, Rahbari H. Eccrine adenocarcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Arch Dermatol 1983;119:104–14. 10.1001/archderm.119.2.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT, et al. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin I. Eccrine carcinomas. Cancer 1985;56:1147–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinkus H, Mehregan AH. Epidermotropic Eccrine Carcinoma. A case combining features of eccrine poroma and paget’s dermatosis. Arch Dermatol 1963;88:597–606. 10.1001/archderm.1963.01590230105015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, et al. Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2017;20:74–9. 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poiares Baptista A, Tellechea O, Reis JP, et al. [Eccrine porocarcinoma. A review of 24 cases]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1993;120:107–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shaw M, McKEE PH, Lowe D, et al. Malignant eccrine poroma: a study of twenty-seven cases. British Journal of Dermatology 1982;107:675–80. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, et al. Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2001;25:710–20. 10.1097/00000478-200106000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veness MJ, Morgan GJ, Palme CE, et al. Surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to lymph nodes: combined treatment should be considered best practice. Laryngoscope 2005;115:870–5. 10.1097/01.MLG.0000158349.64337.ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alam M, Ratner D. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2001;344:975–83. 10.1056/NEJM200103293441306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clayman GL, Lee JJ, Holsinger FC, et al. Mortality risk from squamous cell skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:759–65. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joseph MG, Zulueta WP, Kennedy PJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin of the trunk and limbs: the incidence of metastases and their outcome. Aust N Z J Surg 1992;62:697–701. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07065.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lippman SM, Parkinson DR, Itri LM, et al. 13-cis-retinoic acid and interferon alpha-2a: effective combination therapy for advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Natl Cancer Inst 1992;84:235–41. 10.1093/jnci/84.4.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang NC, Tsai KB. Eccrine porocarcinoma of the auricle: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2009;25:401–4. 10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70534-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Iuliis F, Amoroso L, Taglieri L, et al. Chemotherapy of rare skin adnexal tumors: a review of literature. Anticancer Res 2014;34:5263–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Belin E, Ezzedine K, Stanislas S, et al. Factors in the surgical management of primary eccrine porocarcinoma: prognostic histological factors can guide the surgical procedure. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:985–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Borgognoni L, Pescitelli L, Urso C, et al. A rare case of anal porocarcinoma treated by electrochemotherapy. Future Oncol 2015;11:714 10.2217/fon.14.319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Torchia D, Amorosi A, Cappugi P. Intralesional Photodynamic Therapy for Eccrine Porocarcinoma. Dermatol Surg 2015;41:853–4. 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Huet P, Dandurand M, Pignodel C, et al. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;35(5):860–4. 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90105-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tlemcani K, Levine D, Smith RV, et al. Metastatic apocrine carcinoma of the scalp: prolonged response to systemic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:e412–4. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fujimura T, Hashimoto A, Furudate S, et al. Successful treatment of eccrine porocarcinoma metastasized to a cervical lymph node with CyberKnife Radiosurgery. Case Rep Dermatol 2014;6:159–63. 10.1159/000365348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Plunkett TA, Hanby AM, Miles DW, et al. Metastatic eccrine porocarcinoma: response to docetaxel (Taxotere) chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2001;12:411–4. 10.1023/A:1011196615177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ponzetti A, Ribero S, Caliendo V, et al. Long-term survival after multidisciplinary management of a metastatic sarcomatoid porocarcinoma with repeated exeresis, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and cetuximab: case report and review of literature. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2017;152:66–70. 10.23736/S0392-0488.16.04778-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramaswamy B, Bekaii-Saab T, Schaaf LJ, et al. A dose-finding and pharmacodynamic study of bortezomib in combination with weekly paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2010;66:151–8. 10.1007/s00280-009-1145-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tran DC, Colevas AD, Chang AL. Follow-up on programmed cell death 1 inhibitor for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:92–4. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Borradori L, Sutton B, Shayesteh P, et al. Rescue therapy with anti-programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and basosquamous carcinoma: preliminary experience in five cases. Br J Dermatol 2016;175:1382–6. 10.1111/bjd.14642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chang AL, Kim J, Luciano R, et al. A case report of unresectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma responsive to pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitor. JAMA Dermatol 2016;152:106–8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.2705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]