Abstract

Objectives

To identify factors that predict the quality of life (QoL) of patients with dementia in acute hospitals and to analyse if a special care concept can increase patients’ QoL.

Design

A non-randomised, case–control study including two internal medicine wards from hospitals in Hamburg, Germany.

Setting and participants

In all, 526 patients with dementia from two hospitals were included in the study (intervention: n=333; control: n=193). The inclusion criterion was an at least mild cognitive impairment or dementia. The intervention group was a hospital with a special care ward for internal medicine focusing on patients with dementia. The control group was from a hospital with a regular care ward without special dementia care concept.

Outcome measures

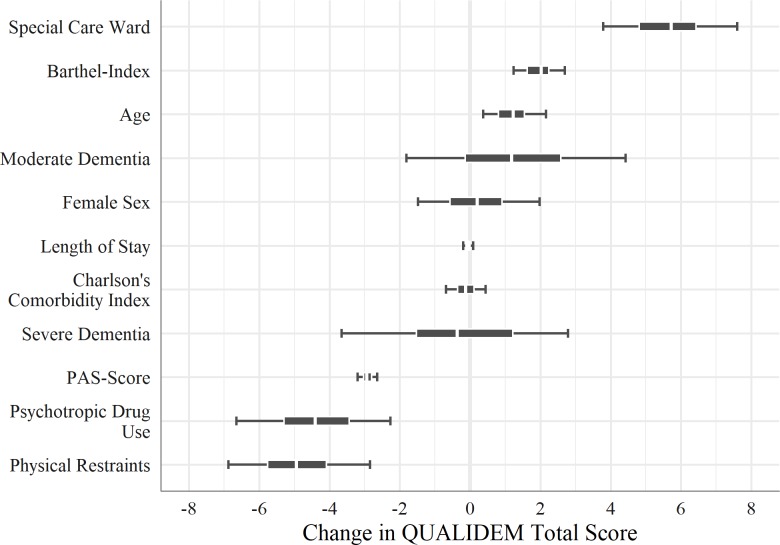

Our main outcome was the QoL (range 0–100) from patients with dementia in two different hospitals. A Bayesian multilevel analysis was conducted to identify predictors such as age, dementia, agitation, physical and chemical restraints, or functional limitations that affect QoL.

Results

QoL differs significantly between the control (40.7) and the intervention (51.2) group (p<0.001). Regression analysis suggests that physical restraint (estimated effect: −4.9), psychotropic drug use (−4.4) and agitation (−2.9) are negatively associated with QoL. After controlling for confounders, the positive effect of the special care concept remained (5.7).

Conclusions

A special care ward will improve the quality of care and has a positive impact on the QoL of patients with dementia. Health policies should consider the benefits of special care concepts and develop incentives for hospitals to improve the QoL and quality of care for these patients.

Keywords: dementia, quality of life, acute hospital, quality of care, internal medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is one of the first studies to investigate quality of life of patients with dementia in acute internal medicine wards in Germany.

The statistical method applied in this study explicitly incorporates and accounts for information and knowledge from previous research.

There are no studies which have evaluated the reliability and validity for the use of the assessment instrument for our main outcome (quality of life) in hospitals settings.

The structural differences between the hospitals from the control and the intervention group may limit the generalisability of the results with regard to the benefit of special care concepts for regular internal medicine wards.

Introduction

Acute hospitals face the challenge of an increase in old age patients, which particularly affects internal medicine wards.1 The average age of patients in internal medicine wards is above 70 years and may even come close to 80 years,2 3 leading to an increasing prevalence of cognitive impairments.4 Although data on the occurrence of dementia or cognitive impairments of patients in hospitals are inconsistent, the larger proportion of studies reports prevalence rates of about 40%.5–7

Many hospitals are insufficiently prepared for patients with cognitive impairments, especially in acute care units predominantly focusing on somatic diseases.8 Patients with cognitive impairments or dementia do not fit into the typical routines and standardised workflows of hospitals as these patients need more resources for care and treatment.9 10 These patients often become disoriented, anxious and agitated, and challenge hospital staff with erratic behaviour when placed in regular care wards. This results in an increased likelihood of falls, complications during the hospital stay and postoperative complications.11 12 Hence, patients with dementia are a vulnerable group with a higher risk for long-lasting functional impairments.13 14

To control the challenging behaviour of patients with dementia, a common practice—at least in German acute hospitals, and especially for older patients—is to use physical restraints such as side rails to keep patients in bed, or chemical restraints such as the on-demand use of psychotropic medication or hypnotics and sedatives.15 16 This practice is not limited to German hospitals; however, there seem to be large variations between countries.17 Physical and chemical restraints as well as anxiety and challenging behaviours are associated with poorer outcomes in quality of life (QoL) and quality of care of patients with dementia.18 19 Therefore, hospitals in general, and specifically internal medicine wards with their increasing proportion of patients with dementia, need to address these issues in order to improve the quality of care for these patients.

At least in Germany, there were lately no care concepts that fully address the needs of patients with dementia in internal medicine.20 The special care ward ‘DAVID’ (Diagnostik, Akuttherapie, Validation auf einer Internistischen Station für Menschen mit Demenz—diagnostic, acute therapy and validation in an internal medicine ward for patients with dementia) in the Protestant Hospital Alsterdorf in Hamburg was one of the first internal medicine wards in Germany that implemented a comprehensive care concept for patients with dementia, aiming to improve patients’ QoL during their hospital stay. QoL is an important indicator of quality of care and a major dimension when assessing patient-reported outcomes, particularly in older people as global outcome measure for interventions.21 22 The assumption of this care concept is that a special care ward for patients with dementia leads to better outcomes in QoL compared with regular internal medicine wards. A study (‘DAVID 2’) was conducted to investigate the impact of such a care concept. This paper shows the results of this study and addresses two research questions: (1) Which factors predict the QoL of patients with dementia in acute hospitals? (2) Beyond these factors, can a special care concept for patients with dementia in acute hospitals increase patients’ QoL?

Methods

Study design and setting

The aim of this study was to compare the quality of care for patients with dementia within a specialised dementia care concept as opposed to regular care in acute hospitals. The present study was designed as a non-randomised, case–control study including two internal medicine wards in two hospitals located in Hamburg, Germany. The intervention group was a hospital that implemented a special care ward for internal medicine focusing on patients with dementia. The control group was from a hospital with a regular care ward for internal medicine which had no special dementia care concept.

Intervention group

The special care ward ‘DAVID’ is an internal medicine ward in the Protestant Hospital Alsterdorf, a not-for-profit organisation, and has 14 beds. In the year of data collection (2016), 349 patients were treated. The ward employed nine care workers as nursing staff.

The following are the key components of the special care concept: (1) a specific architectonical design, including a homelike lounge, a specific colouring of doors and walls, and a light concept with minimum 500 lux at eye level; (2) doctors, nurses and service staff are trained in coping with challenging behaviour and other dementia-related issues, such as basal stimulation or validation therapy, but also included case conferences to discuss issues with current patients23—the duration of training courses and case conferences was about 1 hour and were provided on a monthly basis by external instructors; additionally, twice per year, an internal training course was offered for employees, lasting for half a day; (3) mobile devices for diagnostics, to perform as many treatments as possible in the different rooms of the special care ward; (4) involvement of relatives into assessment, care and discharge planning; and (5) regular therapeutic offers such as occupational or speech therapy, and social offers such as music, playing or spending more time than usual to care for the patients.

To fulfil these high standards of quality of care, the ‘DAVID’ ward employs more care staff in relation to the number of patients as compared with other regular internal medicine wards in Germany. With respect to the total number of full-time equivalents (FTE) nurses, the staff to patient ratio is 1 FTE nurse per 39 patients.

The Protestant Hospital Alsterdorf has a second ward for internal medicine; however, patients with dementia were usually immediately transferred to the special care ward after admission to hospital. Thus, as almost no patients with dementia were treated in the second internal medicine ward, the control group was taken from another hospital.

Control group

The regular care ward is part of a larger private company hospital with emergency hospitalisation. It has 80 beds, and in the year of data collection about 3500 patients were treated in this internal medicine ward. Twenty-six employees worked as care staff in this ward. Trainees sometimes supported the care team. The staff to patient ratio in the regular care ward is approximately 1 FTE nurse per 130 patients. However, since the internal medicine ward in this hospital also treats patients from the emergency ambulance, the staff to patient ratio related to the number of patients who actually stayed longer in hospital (3 days and more) is lower. Unfortunately, the hospital management was not willing to provide more detailed information besides the publicly available quality reports, so we cannot quantify the staff to patient ratio exactly.

The regular care ward had no specific care concept for patients with dementia. The care staff was not particularly trained in dementia topics.

Data collection and participants

An assessment questionnaire was developed to obtain data from patients with dementia. Study nurses were trained in using this assessment questionnaire and then conducted the data collection in both hospitals. Two study nurses were responsible for the special care ward and one for the regular care ward. A pretest of 2 months was conducted to test and revise the questionnaire. As a result, some items were removed and instructions for study nurses were defined more precisely. After the pretest, data were collected over a period of about 12 months (from July 2015 to June 2016 in the special care ward, and from August 2015 to September 2016 in the regular care ward). To detect small to medium effect sizes (Cohen’s d ~0.1 to 0.2), a power analysis was performed prior to the data collection and yielded a sample size of at least 173 subjects per group. Patients were included when they showed at least mild cognitive impairments or memory problems. In the special care ward (intervention group), all patients were assessed because a diagnosed dementia was a requirement for admission to that hospital. Hence, the participation rate for the special care ward was about 94% and excluded only a few patients who were not responsive. For the regular care ward (control group), patients who already had a diagnosed dementia or cognitive impairments were included in the study. A short dementia screening was carried out by the study nurse to assess the severity of dementia of patients who had no clarified dementia diagnosis and to identify further patients who qualify for the study.24 The total sample size for the present analysis consists of n=526 patients (special care ward: n=333; regular care ward: n=193). For both the intervention and the control group, patients were excluded from the study when they were completely confined to bed due to severe health-related dependency. As both care wards had no particular selection criteria for patients such as age, mobility or the main diagnosis that led to hospital admission, no further exclusion criteria for the study were defined.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question nor study design.

Measures

Outcome

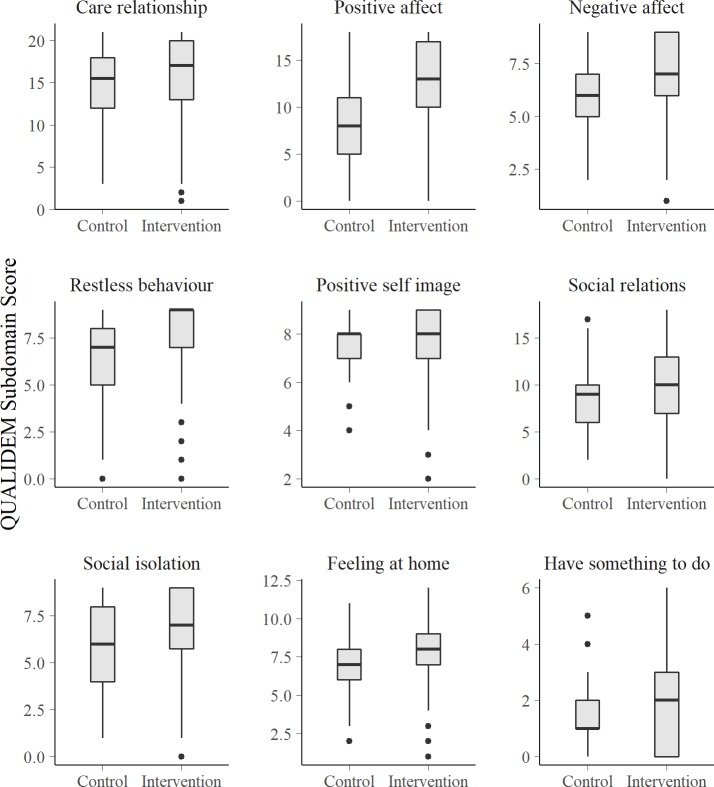

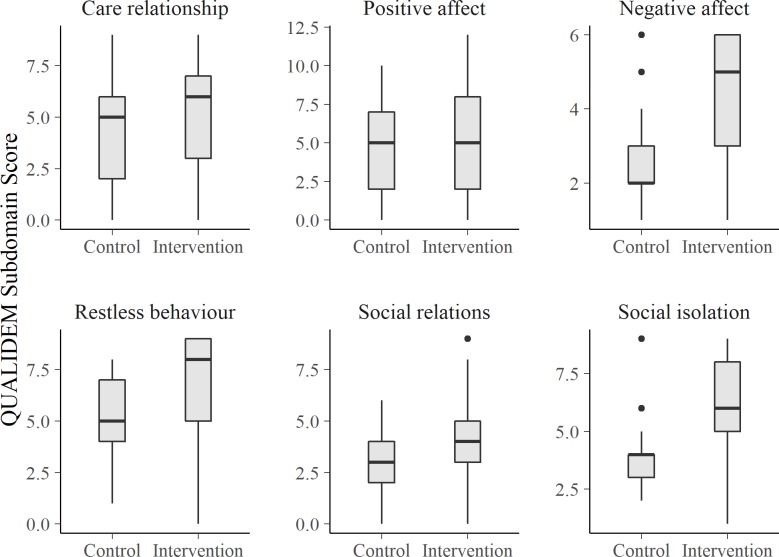

QoL in patients with dementia was assessed using the QUALIDEM.25 26 After observing patients for about 1 week (depending on the length of stay), the study nurses rated their QoL. QUALIDEM comprises 37 items reflecting 9 different subdomains of QoL: ‘care relationship’ (7 items, 0–21 points), ‘positive affect’ (6 items, 0–18 points), ‘negative affect’ (3 items, 0–9 points), ‘restless and tense behaviour’ (3 items, 0–9 points), ‘positive self-image’ (3 items, 0–9 points), ‘social relations’ (6 items, 0–18 points), ‘social isolation’ (3 items, 0–9 points), ‘feeling at home’ (4 items, 0–12 points) and ‘have something to do’ (2 items, 0–6 points). For patients with very severe dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination Test (MMSE)27 <7), only six of the nine subscales apply, where the dimensions ‘positive self-image’, ‘feeling at home’ and ‘have something to do’ were omitted. The recommendation is to report the descriptive results of the QUALIDEM separately for each subscale. For regression analyses, a QoL index was calculated by summing up and normalising the QUALIDEM subscales (six subscales for patients with very severe dementia, nine subscales for the remaining patients) to a range from 0 to 100 points. A higher score indicates better QoL. Due to normalisation of the QUALIDEM total score for all severities of dementia, all patients’ scores are consistent and comparable.28

Independent variables

Age, gender, main diagnosis for admission to hospital and length of stay were recorded. Details about the distribution of the main diagnoses among patients and by hospitals are shown in online supplementary file 1. If a main diagnosis was mentioned no more than one time in both hospital wards, it was recoded into the category ‘other’. The final variable ‘main diagnosis’ comprised 20 different diagnoses. A modified version of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which included depression and hypertension as new items, was built based on the assessment of comorbidities and chronic diseases.29 30 If patients had no chronic illnesses, the CCI had a score of 0. Else, higher scores indicated more serious comorbid disease. Shortly after admission to hospital, the study nurses measured the functional limitations and cognitive status of patients. Functional limitations in daily living were assessed with the Barthel Index.31 This score ranges from 0 (completely dependent) to 100 points (no basic functional limitations) and was recoded according to the the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) (German adaptation)32 into a score from 1 to 6 points. The MMSE27 measures cognitive impairments of patients, ranging from 0 (very strong cognitive impairments) to 30 (very mild or no cognitive impairments) points. This score was recoded into three categories, also based on the ICD-10 classification: severe dementia (0–16), moderate dementia (17–23 points) and mild dementia (24–27 points).

bmjopen-2019-030743supp001.pdf (12.2KB, pdf)

After about 1 week of hospital stay, the study nurses rated the patients’ agitation and challenging behaviour and recorded psychotropic drug use (chemical restraint) and physical restraints. Agitation and challenging behaviour of patients were assessed using the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (PAS),33 ranging from 0 to 16 points (higher scores indicate stronger agitation).

Physical restraints were defined as the use of one of the following measures: side rails to keep a patient in bed, tying a patient to a bed and use of ‘therapeutic’ chairs that prevent patients to stand up. The variable was dichotomised, indicating whether patients (in the course of the hospital stay) were mechanically restrained by at least one of these measures or not.

Psychotropic drug use was defined as on-demand use (‘as-needed’) of medication for the nervous system by means of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification34 and comprises antipsychotics, anxiolytics, hypnotics/sedatives and antidepressants (N05A-C, N06A). Indicated use of psychotropic drugs was defined as medications that were prescribed for regular, not on-demand use and not only given to patients in order to control their challenging behaviour. Such use of psychotropic drugs was excluded from the analysis. The on-demand use variable was dichotomised and shows whether, during the complete hospital stay, chemical restraints were applied to patients or not.

While these variables already cover many different aspects that have an effect on the QoL, we decided to add a further predictor as proxy for the intervention to the model. Therefore, we included a binary variable with two categories (‘control’ as reference and ‘intervention’) representing the two hospitals to estimate the impact of the special care concept. This should reflect how much of the change in QoL is attributable to the special care concept.

Missing data

In total, 11% of individual items across all scales were missing (at random), 6% of individual items when looking at the QUALIDEM only. The missing data pattern was analysed, and missing data were imputed using the multivariate imputation by chained equations method,35 using 11 imputation steps corresponding to the proportion of missing data.36 The method for imputing missing values depends on the variable’s nature. For continuous variables, predictive mean matching was applied, while logistic regressions were used for binary variables.

Statistical methods

Descriptive results for the total sample and each hospital are reported. Statistically significant differences of p<0.05 between the two hospital wards were tested using t-test, χ2 test or Mann-Whitney U test, depending on the level of measurement and distribution of variables. Differences between the hospitals in the QUALIDEM subscales are presented as boxplots, showing the median value and the upper and lower quartiles of the value distribution.

As multivariate analysis, a Bayesian linear mixed model was applied to analyse the associations between the independent variables and the outcome. Computations were based on Stan,37 a probabilistic programming language for specifying Bayesian models, using Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling (in particular, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo).38 We assume that a patient’s main diagnosis is associated with different degrees of physical impairments, which affect the QoL. Therefore, the variable ‘main diagnosis’ was used as level 2 unit (random intercept) in the multilevel model to control for the variation in the outcome. We used informative priors for the predictors age, female gender, severe dementia, psychotic drug use and physical restraints, based on information from former research.18 39 40 Weakly informative priors were used for the remaining predictors. The prior and posterior distributions of the model are summarised in online supplementary file 2.

bmjopen-2019-030743supp002.pdf (495.5KB, pdf)

Continuous predictors were centred before entering the model. Age was divided by 10, so a one-unit change in the predictor of age reflects a change of 10 years in patients. The median value of the posterior distribution is used as ‘Bayesian point estimate’, which minimises the difference of estimates from true values over posterior samples, but there are many other plausible values (the ‘posterior distribution’) to describe the association between predictors and outcome. Hence, 50% and 89% highest density intervals41 are shown to indicate the range of most credible values and to reflect the (un-)certainty of the estimates. The intraclass correlation coefficient42 was calculated to see how much of the proportion of the variance in the outcome can be explained by the grouping structure (‘main diagnosis’). We developed post-hoc additional regression models with interaction terms for need predictors (Barthel Index, physical and chemical restraints, PAS score) to check if the associations between the complexity of patients’ needs and QoL differ between hospitals. We found no significant interaction terms and decided to present the most parsimonious model here and show further results in online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2019-030743supp003.pdf (373.8KB, pdf)

All analyses were conducted with the R statistical package,43 including the packages mice,35 ggplot,44 brms 45 and sjPlot.46 The source code is available in online supplementary file 4. Data are available online.47

bmjopen-2019-030743supp004.pdf (61.4KB, pdf)

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 gives an overview of the sample characteristics. The proportion of female to male patients is similar in both groups. The mean age is 4 years higher in the control group. There are also significant group differences in the Barthel Index indicating higher functional impairment in the control group, while the dementia severity was the same in both hospitals. Comorbid conditions are slightly higher in the control group. Patients stayed 9.4 days in hospital on average and nearly 1 day longer in the intervention group as compared with the control group. Large differences between the two hospitals can be seen in the use of medical and physical restraints, with significantly less use in the intervention group. Agitation and QoL scores also show strong group differences to the disadvantage of the patients in the control group.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristics | Control group (regular care ward, n=193) | Intervention group (special care ward, n=333) | Total (N=526) | P value of difference |

| Female, % | 59.1 | 61.6 | 60.6 | 0.637 |

| Mean age (SD) | 83.1 (7.2) | 79.0 (11.9) | 80.5 (10.6) | <0.001 |

| Mean Barthel Index score (SD) | 29.9 (27.9) | 40.7 (30.4) | 36.7 (29.9) | <0.001 |

| Mild dementia, % | 7.8 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 0.580 |

| Moderate dementia, % | 30.0 | 26.7 | 27.9 | 0.473 |

| Severe dementia, % | 62.2 | 63.7 | 63.2 | 0.805 |

| Mean length of stay, in days (SD) | 8.9 (7.5) | 9.7 (5.5) | 9.4 (6.3) | 0.002 |

| Physical restraints (yes), % | 54.4 | 28.2 | 37.8 | <0.001 |

| Psychotropic drug use (yes, as-needed), % | 25.9 | 14.1 | 18.4 | 0.001 |

| Mean Pittsburgh Agitation Scale score (SD) | 3.9 (3.1) | 3.0 (3.2) | 3.3 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score (SD) | 3.2 (3.0) | 2.5 (2.0) | 2.8 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Mean QUALIDEM total score (SD) | 40.7 (14.5) | 51.2 (17.2) | 47.3 (17.0) | <0.001 |

Barthel Index: 0–100 (higher=better functioning); dementia (MMSE score): mild: 24–27, moderate: 17–23, severe: ≤16; Pittsburgh Agitation Scale: 0–16 (higher=stronger agitation and anxiety); Charlson Comorbidity Index: 0–9 (higher=more comorbidities); QUALIDEM: 0–100 (higher=better QoL).

MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination Test.

In most cases, the distribution of main diagnoses of patients was comparable between the two hospital wards (see online supplementary file 1). The most frequent were pneumonia (13.5% in the intervention group and 11.9% in the control group), a worsening medical condition of patients (8.7% and 7.2%) or exsiccosis (4.8% and 6.7%). Noticeable differences between the two wards were found in urinary tract infections (9.9% in the intervention group and 3.1% in the control group) or dyspnoea (1.2% and 7.8%).

Quality of life

Looking at the QoL for patients with severe to mild cognitive impairments (these are the ones in which all subdomains of the QUALIDEM could be applied), there is a consistent pattern across all QUALIDEM domains: patients in the control group have a lower QoL compared with the intervention group. Except for the last subdomain (‘having something to do’), all differences are statistically significant (figure 1).

Figure 1.

QUALIDEM subdomain scores by care ward in patients with mild to severe dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination Test score from 7 to 27, n=400).

The same consistent pattern can be found for patients with very severe dementia symptoms (MMSE score <7). Here, only the second of the six applied subdomains (‘positive affect’) does not differ significantly between the intervention and the control group (figure 2).

Figure 2.

QUALIDEM subdomain scores by care ward in patients with very severe dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination Test score <7, n=126).

Predictors of QoL

Figure 3 shows the results from the Bayesian mixed model. Three predictors are clearly negatively associated with QoL: physical restraint, psychotropic drug use and agitation (PAS score). Physical restraint is associated with a 4.9-point decrease in QoL. With 50% probability, the QoL decreases by 4.1 to 5.8 points and with a chance of 89% by −7 to −2.8 points, respectively. The application of psychotropic drugs as-needed shows similar results, with a posterior median of −4.4. The third clearly negatively associated predictor is agitation, which shows a decrease in QoL of about 2.9 points for each additional point in the PAS score.

Figure 3.

Predictors of health-related quality of life, regression coefficients, Bayesian linear mixed model and posterior median (+50% and 89% high density interval).

Dementia and gender are not clearly associated with QoL. Neither are the length of hospital stay and the CCI.

The age of the patient correlates slightly positive with QoL, where an increase of 10 years means an increase of about 1.2 points in the QoL. The posterior median of the Barthel Index is 2.0, so for a one-category change in functional impairments the QoL changes by two points. This means that patients with severe functional impairments differ by about 10 points in QoL compared with patients with no functional impairments. Controlling for all other predictors, the intervention (special care ward) shows the strongest association with our outcome of interest, the patients’ QoL. The posterior median is 5.7, and with an 89% probability the credible values describing the effect of the intervention on QoL are within the range from 3.8 to 7.6.

The intraclass correlation coefficient of the model is rather low (0.01). This means the ‘main diagnosis’ does not explain much of the variance in the patients’ QoL, and there is almost no regularisation (‘shrinkage’) of estimated model parameters and no larger differences between hospitals according to the patients’ needs, as indicated by their main diagnosis.

Discussion

The study reported in this paper sought to understand those factors that influence the QoL in patients with dementia and whether a special care concept for these patients performs better in this regard as opposed to regular care wards.

One of our main findings is that QoL differs significantly between the control and the intervention group. We found substantial differences between the two hospitals in the patients’ total QoL score in favour of the special care ward. Beyond the statistical significance, this finding also has a clinical impact. Studies suggest a change in 3 points on the Quality of Life - Alzheimer’s Disease Scale,48 which has a range of 40 points, to be clinically relevant.49 50 Transferred to the range of the QUALIDEM scale, a difference of about 7.5 points would be considered as an important improvement in QoL. Another indicator to evaluate the clinical relevance of a change in QoL is an increase of the score of half an SD,51 which would be about 8.5 points for our data. Taking these reference points as a basis, we found evidence for the clinically relevant improvement in QoL of patients in a special care ward.

A second key finding is the identification of those factors that are clearly associated with QoL. The use of physical and chemical restraints, both happening more frequently in the control group, is associated with lower outcomes in QoL. This finding is in line with other studies that suggest a negative association between physical and chemical restraints and QoL18 40 and explains why the regular care ward performs less good in this regard than the special care ward. Agitation was also negatively associated with QoL. This is understandable as agitation is an expression of anxiety and indisposition of people with dementia and typically occurs after admission to hospital. Furthermore, agitation is often a reason for psychotropic drug use or physical restraint, and thus also negatively affects QoL.52 53

Independent from these factors, the special care ward itself shows the strongest impact on QoL, indicating that patients with dementia explicitly benefit from specialised care concepts. Other studies also report these benefits, both in a nursing home or hospital setting.54 55 Since we controlled for patient characteristics such as main diagnosis, age, functional limitations, chronic comorbidities, agitation, length of stay and so on in our model, we do not assume that the positive effect of the special care ward is completely a result of a biased sample between the intervention and the control group. Although the two compared hospitals differ in their structures and size, patients’ characteristics are largely comparable between the samples in the control and in the intervention group. For instance, there is no substantial difference between the two hospitals regarding the relationship between functional impairments and physical restraints. Moreover, to see if the complexity of patients’ need affects our findings, we calculated regression models with interaction terms between need factors moderated by hospitals (see online supplementary file 3).

The association between complexity of needs and QoL is not significantly different between the intervention and the control group. Based on our results we suggest that the special care concept mainly explains the differences in the QoL. Although it is certainly difficult to determine the exact effect of the special care concept on the patients’ QoL, our findings seem plausible in the light of the key elements of this intervention. A higher ratio of care staff as to patients, smaller facilities or systematically trained employees can be considered essential for healthcare provision to patients with dementia and are much better conditions for less physical or chemical restraints, independent of the functional limitations of patients. The special care ward provides a more dementia-friendly interior design, including orientation and navigation aids and the use of light and colours, which are considered as important components to reduce agitation for patients with dementia.56

These findings and conclusions are in line with other studies on hospital care that suggest that an increased staff ratio or the implementation of multiple components, which particularly address the needs of patients with dementia, leads to reduced use of physical restraints and psychotropic drug use and improves the quality of care.57 58 Furthermore, dementia-specific educational programmes, as implemented in the special care ward, have positive effects on nurses with regard to their interaction with patients with dementia. Trained nurses can improve their coping skills in handling the challenging behaviour of these patients, and better attend to the patients’ unmet physical and psychological needs.59

Studies suggest that the use of both physical and chemical restraints is reduced for nurses who completed a dementia-specific training as opposed to nurses who did not complete such an educational programme. Trained nurses had better skills in providing patient-centred care and thus improving the QoL for patients with dementia.59–61 The special care ward benefits from a higher staff ratio, that is, nurses have to care for fewer patients with dementia compared with the control group. While this is an intentional element of the concept, the downside is higher personnel costs. Only few studies investigated the follow-up costs for patients with dementia in home care settings after hospitalisation. Costa et al 62 predicted additional monthly costs in home care of about €445 due to increased agitation of patients with dementia. Thus, if patients with dementia benefit from special care concepts and perceive better outcomes in quality of life and care, the increased costs for more care personnel may be compensated by reducing follow-up costs for the ambulatory care. However, further research is needed to give more exact projections of the increased costs and potential of saving money.

Another finding is that the severity of cognitive impairments, measured with the MMSE, is a rather improper indicator to represent the underlying problems of and with the dementia disease, as these factors were not consistently associated with QoL. Direct measures of the problems associated with dementia, as agitation or challenging behaviour, should be considered as well when it comes to investigating the QoL of patients with dementia.

Our study has several limitations. One concerns the structural differences between the two hospitals. The hospital with the special care ward is much smaller than the hospital that hosted the control group. A second control group or an intervention group in a hospital of a similar size as the hospital with the regular care ward may have permitted a more distinct comparison. We tried to keep the impact of the structural differences as minimal as possible, for instance by accounting for many different patient characteristics including functional status, comorbidities and behavioural problems.

Furthermore, the main diagnoses of patients were also considered in the analysis. We assume that we could at least partly adjust our analysis for a bias due to patient selection mechanisms. To validate our assumptions, we investigated to which extent the association between patient characteristics and QoL is affected by differences between the control and the intervention group (details shown in online supplementary file 3). Results suggest that our data provide no strong evidence for noticeable differences between the intervention and the control group with regard to the association between complexity of patients’ needs and QoL. However, although we adjusted our analysis for many patient characteristics, we cannot eliminate a potential bias due to different hospital structures. In particular, the higher mean age and stronger functional limitations in the control group may indicate a selection bias in our sample. We suggest that further studies should take a second control group or a more comparable intervention group into account to gain more insight into potential biases due to structural differences of the control and the intervention group.

Another structural difference between the intervention and the control group that certainly affects the results are the different staff to patient ratios. In the special care ward, nurses have to care for fewer patients than in the regular care ward. Although we assume that this aspect probably has the highest impact on the outcomes in QoL, this is not a ‘selection bias’ per se rather than a core component of the intervention. A higher staff to patient ratio, dementia-specific training programmes or a specific architectonical design are key elements of the special care concept, which, in their entirety, are reflected in the resulting differences between hospitals.

A further limitation is possibly the first and thus rather exploratory use of the QUALIDEM assessment in a hospital setting. Although studies show reliable results of the QUALIDEM in nursing homes even for a short observation period of about 1 week,63 there are no studies that evaluate the reliability and validity for use in hospitals. We have done checks of internal consistencies, which showed that most subdomains of the QUALIDEM perform well with our data and are comparable with results from other validation studies.64 This indicates that the use of the QUALIDEM is feasible for hospital research. However, due to financial and logistic limitations, it was not possible to monitor the complete data collection and accurate completion of questionnaires. Hence, we cannot give evidence on the inter-rater reliability apart from the intense training of the study nurses.

Another debatable issue regarding the QUALIDEM concerns the computation concept of the total score for patients with very severe dementia. We followed the QUALIDEM authors’ instruction to use only six of the nine subscales to calculate the total score for this group.65 Technically, this is similar to mean value imputation for the missing scores of the three omitted subscales. This, however, may result in biased and/or underestimated measurement error variance for this group. Therefore, we also calculated a regression model with a QUALIDEM total score based on imputation for missing values for all nine subscales for patients with very severe dementia (see online supplementary file 5). In the Results section, we have provided the analyses as suggested by the QUALIDEM authors for comparability reasons. In order to meet different views on the computation concept, we also provide the results of the alternative analysis in online supplementary file 5. These are very similar to the first analysis and do not differ significantly.

bmjopen-2019-030743supp005.pdf (139.8KB, pdf)

Finally, due to the nature of the study design, it was not possible that study nurses in the intervention and the control group were blinded. This might affect the results insofar as study nurses may have generated more generous responses for the assessment scales.66

Conclusions

On the whole, we think that a special care ward will improve the quality of care and is effective with regard to the positive impact on the QoL of patients with dementia. Our study showed that after controlling for different predictors, the intervention still has a perceptible effect concerning clinically important differences in our outcome of interest, the patients’ QoL. However, such improvements can only be achieved by implementing a concept with multiple components that address the explicit needs of patients with dementia. The implementation of a special care concept usually increases the costs for hospitals because it requires a higher staff to patient ratio, regular training of employees or more therapeutic offers. On the other hand, costs that accumulate in informal care after hospital stay as a result of poorer quality of care in hospitals can be much higher than additional personnel costs and could probably be reduced.62 67 Health policies should consider the benefits of special care concepts and develop incentives for hospitals to improve the QoL and quality of care for patients with dementia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the clinical staff of both hospitals who supported this study by helping with the data collection. Furthermore, the authors are thankful to the Authority of Health and Consumer Protection and the Homann Foundation for funding this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: DL was involved in the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the article. GP was involved in the conception and design of the study and interpretation of data. JK was involved in the interpretation of data and drafting the article. CK was involved in the conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and drafting the article.

Funding: The present study was funded by the Behörde für Gesundheit und Verbraucherschutz (Authority of Health and Consumer Protection) in Hamburg and the Homann Foundation (grant number Z/65454/2014/F500-02.10/10,002). None of the funders was involved in the data analysis process and did not influence or hold back the results of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Prior to the study, a study protocol was developed and submitted to the ethical committee of the medical association of Hamburg ('Ethik-Kommission der Ärztekammer Hamburg'). The IRB of the ethical committee approved the proposal and attested that the study conforms to ethical and legal requirements (approval code PV5102). Study participants were not able to give their informed consent due to their cognitive impairments. However, as data mostly derived from the hospitals’ regular documentation and were completely anonymous, the IRB of the ethics committee waived the need of an informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available in a public, open access repository.

References

- 1. Recine U, Scotti E, Bruzzese V, et al. The change of hospital internal medicine: a study on patients admitted in internal medicine wards of 8 hospitals of the Lazio area, Italy. Ital J Med 2015;9 10.4081/itjm.2015.523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raveh D, Gratch L, Yinnon AM, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients admitted to medical departments. J Eval Clin Pract 2005;11:33–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2004.00492.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sonnenblick M, Raveh D, Gratch L, et al. Clinical and demographic characteristics of elderly patients hospitalised in an internal medicine department in Israel: characteristics of elderly patients in medical wards. Int J Clin Pract 2007;61:247–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mukadam N, Sampson EL. A systematic review of the prevalence, associations and outcomes of dementia in older General Hospital inpatients. Int Psychogeriatr 2011;23:344–55. 10.1017/S1041610210001717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zekry D, Herrmann FR, Grandjean R, et al. Does dementia predict adverse hospitalization outcomes? A prospective study in aged inpatients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:283–91. 10.1002/gps.2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Rabins PV. Dementia in elderly persons in a general Hospital. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:704–7. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, et al. Dementia in the acute Hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:61–6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pinkert C, Holle B. Menschen mit Demenz im Akutkrankenhaus: Literaturübersicht zu Prävalenz und Einweisungsgründen. Z Für Gerontol Geriatr 2012;45:728–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dutzi I, Schwenk M, Micol W, et al. Patienten mit Begleitdiagnose Demenz. Z Gerontol Geriat 2013;46:208–13. 10.1007/s00391-013-0483-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Timmons S, O'Shea E, O'Neill D, et al. Acute Hospital dementia care: results from a national audit. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:113 10.1186/s12877-016-0293-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pi H-Y, Gao Y, Wang J, et al. Risk factors for in-hospital complications of fall-related fractures among older Chinese: a retrospective study. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:8612143 10.1155/2016/8612143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hu C-J, Liao C-C, Chang C-C, et al. Postoperative adverse outcomes in surgical patients with dementia: a retrospective cohort study. World J Surg 2012;36:2051–8. 10.1007/s00268-012-1609-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Motzek T, Junge M, Marquardt G. Einfluss der Demenz auf Verweildauer und Erlöse im Akutkrankenhaus. Z Gerontol Geriat 2017;50:59–66. 10.1007/s00391-016-1040-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gross AL, Jones RN, Habtemariam DA, et al. Delirium and long-term cognitive trajectory among persons with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1324 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nakanishi M, Okumura Y, Ogawa A. Physical restraint to patients with dementia in acute physical care settings: effect of the financial incentive to acute care hospitals. Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30:991–1000. 10.1017/S104161021700240X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Krüger C, Mayer H, Haastert B, et al. Use of physical restraints in acute hospitals in Germany: a multi-centre cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1599–606. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Heinze C, Dassen T, Grittner U. Use of physical restraints in nursing homes and hospitals and related factors: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1033–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beerens HC, Sutcliffe C, Renom-Guiteras A, et al. Quality of life and quality of care for people with dementia receiving long term institutional care or professional home care: the European RightTimePlaceCare study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:54–61. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beerens HC, Zwakhalen SMG, Verbeek H, et al. Factors associated with quality of life of people with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:1259–70. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kricheldorff C, Hofmann W. Demenz im Akutkrankenhaus. Z Gerontol Geriat 2013;46:196–7. 10.1007/s00391-013-0484-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Treurniet HF, Essink-Bot M-L, Mackenbach JP, et al. Health-related quality of life: an indicator of quality of care? Qual Life Res 1997;6:363–9. 10.1023/A:1018435427116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Valderas JM, Alonso J. Patient reported outcome measures: a model-based classification system for research and clinical practice. Qual Life Res 2008;17:1125–35. 10.1007/s11136-008-9396-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tondi L, Ribani L, Bottazzi M, et al. Validation therapy (VT) in nursing home: a case-control study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2007;44:407–11. 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaiser AK, Hitzl W, Iglseder B. Three-question dementia screening: development of the Salzburg dementia test prediction (SDTP). Z Für Gerontol Geriatr 2014;47:577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ettema TP, Dröes R-M, de Lange J, et al. QUALIDEM: development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument. Scalability, reliability and internal structure. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:549–56. 10.1002/gps.1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dichter MM, Ettema TP, Schwab CGG, et al. Benutzerhandbuch für die deutschsprachige QUALIDEM version 2.0. Witten, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, et al. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dichter MN, Meyer G. Quality of Life of People with Dementia in Nursing Homes : Schüssler S, Lohrmann C, Dementia in nursing homes. Cham: Springer, 2017: 139–57. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Charlson ME, Charlson RE, Peterson JC, et al. The Charlson comorbidity index is adapted to predict costs of chronic disease in primary care patients. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:1234–40. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J 1965;14:61–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deutsches Institut f. medizinische Dokumentation u. Information (DIMDI) ICD-10-GM 2017 Systematisches Verzeichnis. Lich, Hess: pictura Werbung, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rosen J, Burgio L, Kollar M, et al. The Pittsburgh agitation scale: a User‐Friendly instrument for rating agitation in dementia patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994;2:52–9. 10.1097/00019442-199400210-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2013. Oslo, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. van BS, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by Chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45. [Google Scholar]

- 36. White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med 2011;30:377–99. 10.1002/sim.4067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carpenter B, Gelman A, Hoffman MD, et al. Stan : A Probabilistic Programming Language. J Stat Softw 2017;76 10.18637/jss.v076.i01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, et al. Bayesian data analysis. 3rd edn Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barca ML, Engedal K, Laks J, et al. Quality of life among elderly patients with dementia in institutions. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2011;31:435–42. 10.1159/000328969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beer C, Flicker L, Horner B, et al. Factors associated with self and informant ratings of the quality of life of people with dementia living in care facilities: a cross sectional study. PLoS One 2010;5:e15621 10.1371/journal.pone.0015621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McElreath R. Statistical rethinking: a Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan. Boca Raton London New York: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hox JJ. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. 2nd edn New York: Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 43. R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R foundation for statistical computing, 2019. Available: https://www.R-project.org/

- 44. Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. 2nd edn New York: Springer, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bürkner P-C. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Softw 2017;80. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lüdecke D. sjPlot: data visualization for statistics in social science, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lüdecke D. Dataset: quality of life of patients with dementia in acute Hospitals- version 1.0, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thorgrimsen L, Selwood A, Spector A, et al. Whose quality of life is it anyway? The validity and reliability of the quality of Life-Alzheimer's disease (QoL-AD) scale. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2003;17:201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Selwood A, Thorgrimsen L, Orrell M. Quality of life in dementia?a one-year follow-up study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:232–7. 10.1002/gps.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoe J, Hancock G, Livingston G, et al. Changes in the quality of life of people with dementia living in care homes. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:285–90. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318194fc1e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: the remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med Care 2003;41:582–92. 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062554.74615.4C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lam K, Kwan JSK, Wai Kwan C, et al. Factors associated with the trend of physical and chemical restraint use among long-term care facility residents in Hong Kong: data from an 11-year observational study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:1043–8. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ó Flatharta T, Haugh J, Robinson SM, et al. Prevalence and predictors of bedrail use in an acute Hospital. Age Ageing 2014;43:801–5. 10.1093/ageing/afu081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kok JS, Berg IJ, Scherder EJA. Special care units and traditional care in dementia: relationship with behavior, cognition, functional status and quality of life - a review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2013;3:360–75. 10.1159/000353441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. von Renteln-Kruse W, Neumann L, Klugmann B, et al. Geriatric patients with cognitive impairment. Dtsch Ärztebl Int 2015;112:103–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Büter K, Motzek T, Dietz B, et al. Demenzsensible Krankenhausstationen: Expertenempfehlungen zu Planung und Gestaltung. Z Für Gerontol Geriatr 2017;50:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Blair A, Anderson K, Bateman C. The "Golden Angels": effects of trained volunteers on specialling and readmission rates for people with dementia and delirium in rural hospitals. Int Psychogeriatr 2018;30:1707–16. 10.1017/S1041610218000911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sinvani L, Warner-Cohen J, Strunk A, et al. A multicomponent model to improve hospital care of older adults with cognitive impairment: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1700–7. 10.1111/jgs.15452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Schindel Martin L, Gillies L, Coker E, et al. An education intervention to enhance staff self-efficacy to provide dementia care in an acute care hospital in Canada: a nonrandomized controlled study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2016;31:664–77. 10.1177/1533317516668574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matsuda Y, Hashimoto R, Takemoto S, et al. Educational benefits for nurses and nursing students of the dementia supporter training program in Japan. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200586 10.1371/journal.pone.0200586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Galvin JE, Kuntemeier B, Al-Hammadi N, et al. "Dementia-friendly hospitals: care not crisis": an educational program designed to improve the care of the hospitalized patient with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2010;24:372–9. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181e9f829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Costa N, Wübker A, De Mauléon A, et al. Costs of care of agitation associated with dementia in 8 European countries: results from the RightTimePlaceCare study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19:95.e1–10. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dichter MN, Schwab CGG, Meyer G, et al. Item distribution, internal consistency and inter-rater reliability of the German version of the QUALIDEM for people with mild to severe and very severe dementia. BMC Geriatr 2016;16 10.1186/s12877-016-0296-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dichter M, Dortmann O, Halek M, et al. Scalability and internal consistency of the German version of the dementia-specific quality of life instrument QUALIDEM in nursing homes – a secondary data analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:91 10.1186/1477-7525-11-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dichter MN, Quasdorf T, Schwab CGG, et al. Dementia care mapping: effects on residents’ quality of life and challenging behavior in German nursing homes. A quasi-experimental trial. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:1875–92. 10.1017/S1041610215000927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Blinding in randomised trials: hiding who got what. Lancet 2002;359:696–700. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Leon J, Cheng C-K, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer's disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Aff 1998;17:206–16. 10.1377/hlthaff.17.6.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-030743supp001.pdf (12.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030743supp002.pdf (495.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030743supp003.pdf (373.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030743supp004.pdf (61.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-030743supp005.pdf (139.8KB, pdf)