Abstract

Objective:

To examine parents’ interest in continuing and willingness to pay (WTP) for two pediatric weight management programs following their participation.

Methods:

Participants were parents of 2–12 year-olds with BMI ≥85th percentile who participated in the Connect for Health trial. One group received enhanced primary care (EPC) and the other received EPC plus individualized coaching (EPC+C). At 1-year, we assessed parents’ self-reported WTP for a similar program and the maximum amount ($US/month) they would pay. We used multivariable regression to examine differences in WTP and WTP amount by intervention arm and by individual and family-level factors.

Results:

Of 638 parents who completed the survey, 85% were interested in continuing and 38% of those parents were willing to pay; 31% in the EPC group and 45% in the EPC+C group. The median amount parents were willing to pay was $25/month (interquartile range $15; $50). In multivariable models, EPC+C parents were more likely to endorse WTP than EPC parents (Odds Ratio 1.53; 95% CI, 1.05–2.22). Parents of children with Hispanic/Latino v. White ethnicity and those reporting higher satisfaction with the program were also more likely to endorse WTP.

Conclusions:

Most parents of children in a weight management program were interested in continuing it after it ended, but fewer were willing to pay out of pocket for it. A greater proportion of parents were willing to pay if the program included individualized health coaching.

Keywords: Obesity, Willingness to pay, weight management program, pediatrics

Introduction

Pediatric overweight and obesity remain highly prevalent, both in the U.S. and abroad. Several interventions to address obesity in children have been shown to be effective, some of which include individualized health coaching.1 However, those interventions vary in both intensity and expense.2 To scale these interventions broadly, there may need to be cost sharing with families or other payers, but little is known about what parents of children with overweight or obesity would be willing to pay for weight management programs.

Willingness to pay (WTP) is a commonly used metric to assess the value of a good or service and is used widely in the cost-benefit analyses of programs and policies.3, 4 WTP analyses can provide valuable information to payers and policymakers, both about the value of different policy targets as well as the financial viability of specific programs.5

One study in adults evaluated the WTP of participants to continue a lifestyle-based weight loss program they had been engaged in for 24 months.8 In this study, the intervention resulted in significant weight loss compared to control. The median amount participants were willing to pay out of pocket for the intervention at the end of the trial was $45/month.8 This amount was higher than other studies that surveyed a general population about hypothetical weight loss medicine or low-calorie diet (median WTP out of pocket of $10–12/month),9 but much lower than the median of $1300/month out of pocket found in another study surveying adults with obesity about WTP for an effective, but hypothetical weight loss treatment.10

Several studies have examined WTP for pediatric obesity and overweight management. These studies have been limited, however, by evaluating WTP for the prevention of obesity rather than treatment,6 surveying a general population (rather than patients or parents with obesity),7 or using hypothetical treatment scenarios.6

In this study, we aimed to determine the factors associated with parental interest to continue, and WTP out of pocket, for two pediatric weight management programs after the completion of the Connect for Health trial.11 We also aimed to determine factors associated with the amount parents were willing to pay. We specifically examined the extent to which intervention arm assignment was associated with WTP outcomes. We hypothesized that a majority of parents would be interested in continuing a weight management program and those who received individualized health coaching would be more willing to pay out-of-pocket to do so.

Methods

The Connect for Health study was a randomized trial of pediatric weight management in six medical offices of a multispecialty group practice in Massachusetts conducted from June 2014 to March 2016. Details of the protocol and the main results of the trial can be found elsewhere.11, 12 Briefly, participants were children aged 2–12 years with BMI ≥85th percentile and their parents. Participants were randomized to one of two intervention arms: (1) enhanced primary care (EPC), or (2) enhanced primary care plus contextually-tailored, individual health coaching (EPC+C). The two interventions resulted in improved family-centered outcomes and statistically significant improvements in child BMI: an improvement of −0.06 BMI z score units (95% CI, −0.10 to −0.02) for the EPC group and of −0.09 BMI z score units (95% CI, −0.13 to −0.05) for the EPC+C group. Participants completed telephone surveys both at baseline and one year later at the end of the trial. Study activities were approved by the Partners Health Care Institutional Review Board. The trial has been recorded in clinicaltrials.gov.

Interventions

Connect for Health included two intervention arms. The enhanced primary care (EPC) arm consisted of flagging pediatric patients with BMI ≥ 85th percentile in the electronic health record for primary care providers, clinical decision support tools for pediatric weight management, parent educational materials, a Neighborhood Resource Guide, and monthly text messages. The EPC+C arm included enhanced primary care as defined above plus contextually-tailored, individual health coaching, i.e. twice-weekly text messages and telephone or video contacts every other month to support behavior change and link families to neighborhood resources.

Outcome Measures

Our main outcome was parents’ WTP for a weight management program. Using surveys at 1-year, we asked parents about their interest in continuing the program, their perceived worth of the program (in dollars per month), their WTP out of pocket for the program, and the amount they would be willing to pay per month for the program. Specifically, we first asked every parent: “Thinking about all the components of Connect for Health, which included text messages, information about community resources and possibly health coaching, how interested would you be in continuing a program like this?”. The three answer choices (not at all interested, somewhat interested, very interested) were then dichotomized to not interested vs. interested.

We then asked each parent about their perception of worth of the program by asking a single open-ended question: “How much do you think the Connect for Health program is worth in dollars per month?”. To diminish the influence of outliers, winsorization of data to $1000 was applied to sixteen values that were either non-numerical (ex: millions) or that were above the 95th percentile of the distribution (>$1000/month).

We then asked: “Thinking about your current monthly budget, would you be willing to pay out of pocket for a program like Connect for Health?” Similarly to other studies, the three possible answers (yes, no, unsure) were dichotomized to yes vs. no/unsure.8 For this outcome, we restricted our analysis to parents who were interested in continuing the program.

Finally, we asked parents how much they would be willing to pay per month for the program. For this outcome, we limited our analysis to participants who reported being willing to pay out of pocket in the previous question. There is ongoing debate in the literature as to the best method to elicit WTP.13 One technique previously used in other studies investigating the value of weight-control treatment,9 is the open-ended question method, where participants are simply asked the amount they are willing to pay using a single, open-ended question.13 Others have instead advocated for using the bidding game, or WTP by iteration, a series of binary questions, offering a first amount (for example $10), and if participants are ready to pay at least that amount, a higher one is proposed ($20) and this process is repeated until a maximum amount is found.13, 14 When using the WTP by iteration method, it is common to randomize participants to start with either a lower bound ($10) or an upper bound ($100) and move in the other direction, in an effort to mitigate anchoring, or starting-point bias.8, 14, 15

Given the lack of consensus in the literature on measuring WTP, in this study we first elicited willingness to pay using the WTP by iteration method (including randomization of the starting point) then followed by an open-ended question format to clarify the maximum they would pay within the range they had selected. In the multivariable analysis, we adjusted for the starting point ($10 or $100) to which participants were randomized.

Predictors at baseline

In addition to the intervention arm, the following factors were considered as potential predictors of parents’ interest in continued participation and WTP. Using surveys at baseline, we obtained child’s race/ethnicity, parent’s age and educational attainment as well as annual household income. Education was dichotomized for multivariable analyses. Also at baseline, we obtained children’s sex, age, height, and weight (to calculate BMI) from the electronic health records. We categorized child’s BMI as overweight if the BMI was between the 85th and the 95th percentile, obesity if BMI was between the 95th percentile and 120% of the 95th percentile, and severe obesity if BMI was greater than or equal to 120% of the 95th percentile.11, 16, 17

Mediators at follow-up

At 1-year, we assessed change in child’s BMI category and parental satisfaction with the program. A child was either categorized as being at a lower BMI category at follow-up than baseline or at the same/higher BMI category at baseline.11 We determined parental satisfaction by asking, “Overall, how satisfied are you with your experience in the Connect for Health program?”. The four possible answers (very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat unsatisfied and very unsatisfied) were dichotomized to somewhat, or very satisfied vs. somewhat, or very dissatisfied.

Statistical Methods

We used Fisher’s exact test to compare responses between intervention arms for the dichotomous outcomes of interest to continue participating in and willingness to pay out of pocket for the program. Given the non-Gaussian distribution of the perceived worth of the program, and of the maximum dollar amount participants were willing to pay ($ WTP), we used Wilcoxon rank sum test to compare the outcome between intervention groups. We developed multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the effect of the covariates on the odds of reporting interest to continue and WTP out of pocket. We present a sequence of models, each including an additional set of predictors. Specifically, we first created models with only the baseline predictors (demographics with and without BMI category), and then added the mediators obtained at the end of the trial (BMI change, satisfaction with the program, perceived worth). We first built models using baseline characteristics, in an attempt to approximate as closely as possible the information that would be available at the beginning of a weight management program offered outside of a clinical trial. We adjusted for baseline characteristics given that not all participants answered the question on interest to continue the program, therefore not maintaining randomization. We also created median regression models to determine the contribution of each covariate on the perceived monetary worth of the program, and the amount participants were willing to pay ($ WTP). Confidence intervals for these models were obtained by the repeated sampling method. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 721 participants enrolled in the trial, and 638 (88%) parents completed the 1-year follow-up survey including questions related to WTP. Mean (SD) age of the children was 8.0 (3.0) years and 42% had household incomes <$50,000/year. Details of the demographic characteristics for the sample are shown in Table 1. There were no major differences between the two groups with regards to any of the demographic characteristics measured.

Table 1:

Characteristics of participants in the Connect for Health study

| Child’s characteristics | Study Arm |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| All (N=638) |

EPC (N=323) |

EPC+C (N=315) |

|

| Age, years | 8.1 (3.0) | 8.0 (3.0) | 8.1 (3.0) |

| 2–6 years old | 165 (25.9%) | 87 (26.9%) | 78 (24.8%) |

| 6–12 years old | 473 (74.1%) | 236 (73.1%) | 237 (75.2%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 329 (51.6%) | 170 (52.6%) | 159 (50.0%) |

| Male | 309 (48.4%) | 153 (47.4%) | 156 (50.0%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 228 (35.7%) | 123 (38.1%) | 105 (33.3%) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 216 (33.9%) | 100 (31.0%) | 116 (36.8%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 132 (20.7%) | 71 (22.0%) | 61 (19.4%) |

| Other | 62 (9.7%) | 29 (9.0%) | 33 (10.5%) |

| BMI category at baseline | |||

| 85th to <95th percentile | 230 (36.1%) | 110 (34.1%) | 120 (38.1%) |

| 95th to 120% of 95th percentile | 267 (41.9%) | 142 (44.0%) | 125 (39.7%) |

| >120% of the 95th percentile | 141 (22.1%) | 71 (22.0%) | 70 (22.2%) |

| BMI category change | |||

| Decreased | 123 (20.4%) | 64 (21.2%) | 59 (19.7%) |

| Stayed the same or increased | 479 (79.6% | 238 (78.8%) | 241 (80.3%) |

| Mean BMI z-score at baseline (SD) | 1.91 (0.56) | 1.87 (0.56) | |

| Mean BMI z-score change (95% C.I.) | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.02) | −0.09 (−0.13, −0.05) | |

| Parent and household’s characteristics | |||

| Income category | |||

| ≤$50K/year | 262 (41.9%) | 119 (37.5%) | 143 (46.4%) |

| >$50K/year | 363 (58.1%) | 198 (62.5%) | 165 (53.6%) |

| Parent educational attainment | |||

| 8th Grade Or Less (0–8) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Some High School (9–11) | 12 (1.9%) | 5 (1.6%) | 7 (2.2%) |

| High School Graduate (12) | 70 (11.0%) | 45 (13.9%) | 25 (8.0%) |

| Some College Or Technical School (13–15) | 221 (34.8%) | 113 (35.0%) | 108 (34.5) |

| College Graduate (16) | 208 (32.7%) | 97 (30.0%) | 111 (35.5%) |

| Postgraduate Training Or Degree (17+) | 124 (19.5%) | 62 (19.2%) | 62 (19.8%) |

| Satisfaction with the program | |||

| Somewhat, or very satisfied | 560 (88.8%) | 254 (80.1%) | 306 (97.5%) |

| Somewhat, or very dissatisfied | 71 (11.2%) | 63 (19.9%) | 8 (2.6%) |

Effect of health coaching

Overall, the majority of parents (84.6%) were interested in continuing the program in which they participated. In bivariate analyses, parents in the EPC+C arm were more likely to report being interested in continuing the program than parents in the EPC arm (88.6% vs. 80.8%, p=0.007). The median amount (IQR) parents perceived the program to be worth was $30/month ($10-$100/month); $20 ($5-$100) for the EPC group and $50 ($20-$150) for the EPC + C group (p<0.001). Among those interested in continuing the program, parents in the EPC+C arm were more likely to report being willing to pay out-of-pocket for the program (44.6% vs. 31.1%, p<0.001). Among parents interested in continuing the program and who were willing to pay, the median amount (IQR) they were willing to pay was $25/month ($15-$50), and this amount was higher for parents in the EPC+C arm than for those in the EPC arm (median $27.5 vs. $20, p=0.04).

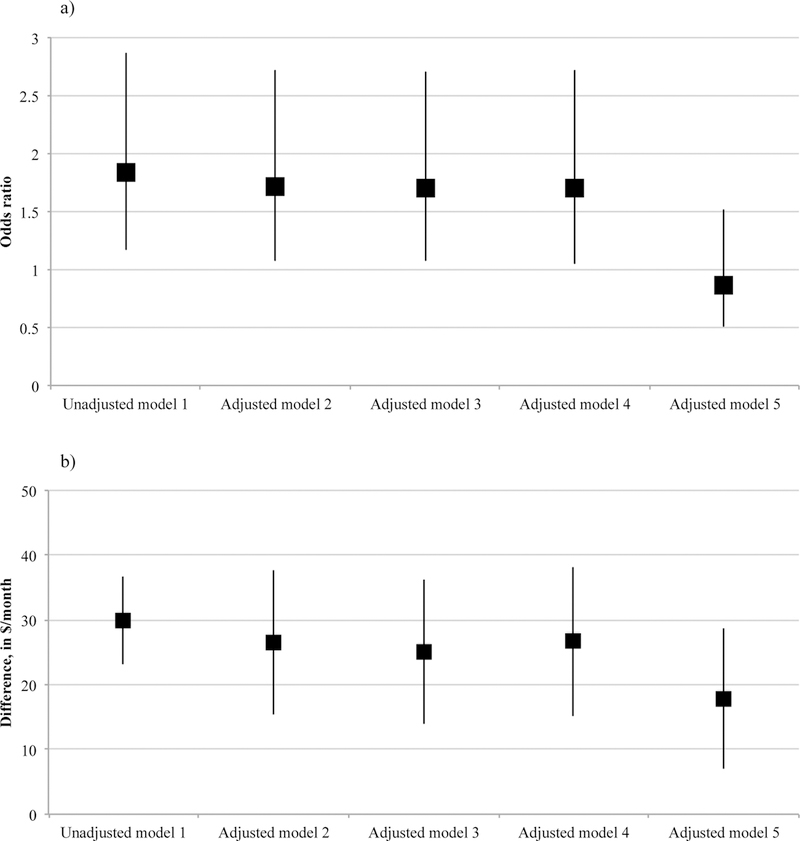

We examined the effect of the intervention arm on the outcomes, using sequential multivariable regression models. The higher odds of reporting interest in continuing the program for parents in the EPC+C arm persisted after adjusting for baseline predictors and BMI category change. However, adjustment for satisfaction with each program attenuated the odds ratio, such that we found no difference across the two intervention arms (OR 0.87, 95% CI, 0.51–1.51) (Figure 1a and Table 2).

Figure 1:

Difference in interest to continue (a), perceived worth of the program (b), for participants in the EPC+C arm vs. EPC arm

Legend: Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Model 1: Intervention arm (REF=EPC)

Model 2: Model 1 + child age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income category

Model 3: Model 2 + baseline BMI category

Model 4: Model 3 + BMI category change

Model 5: Model 4 + satisfaction with the program

Table 2:

Effect of different factors influencing parental interest to continue, perceived worth, willingness to pay, and amount ($/month) parents were willing to pay, in multivariate models.

| Interest to continue (n=586) Being somewhat/very interested vs. Not interested (Model 5, Figure 1a) |

Perceived worth of the program in U.S. dollars/month (n=535) (Model 5, Figure 1b) |

Willingness to pay (n=535) Being somewhat/very interested vs. Not interested (Model 6, Figure 2a) |

Willingness to pay in U.S. dollars/month (n=217) (Model 7, Figure 2b) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Difference (95% C.I.) in median $/month | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | Difference (95% C.I.) in median $/month | |

| Intervention arm | ||||

| EPC+C (vs. EPC) | 0.87 (0.51, 1.51) | 17.90 (7.03, 28.77) | 1.53 (1.05, 2.22) | 5.77 (−1.50; 13.04) |

| Child’s characteristics | ||||

| Age - 6–12 years old (vs. 2–6 y.o.) | 0.62 (0.33, 1.16) | 11.30 (2.40, 20.20) | 0.99 (0.66, 1.50) | 3.46 (−4.26, 11.18) |

| Gender - Female (vs. Male) | 1.02 (0.62, 1.69) | 1.10 (−6.90, 9.10) | 0.82 (0.57, 1.18) | −2.88 (−9.66, 3.89) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.74 (0.91, 3.30) | 18.90 (1.48, 36.32) | 1.12 (0.70, 1.81) | 3.65 (−6.57, 13.88) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 2.85 (1.33, 6.09) | 16.80 (0.29, 33.31) | 1.93 (1.14, 3.27) | 1.15 (−10.11, 12.41) |

| Other | 2.28 (0.81, 6.40) | 10.50 (−2.14, 23.14) | 1.11 (0.56, 2.19) | 5.38 (−5.69, 16.46) |

| BMI category at baseline | ||||

| 85th to <95th percentile | REF | REF | REF | REF |

| 95th to 120% of 95th percentile | 0.78 (0.45, 1,37) | 1.80 (−5.97, 9.57) | 0.98 (0.64, 1.49) | 4.42 (−3.15, 12.00) |

| >120% of the 95th percentile | 1.68 (0.75, 3.75) | 0.00 (−16.06, 16.06) | 0.90 (0.53, 1.53) | 4.04 (22127.99, 16.07) |

| BMI category change after 1 year | ||||

| Decreased (vs. Stayed same or increased) | 0.57 (0.32, 1.02) | −0.80 (−9.00, 7.40) | 0.84 (0.53, 1.34) | 6.73 (−2.22, 15.68) |

| Parent and household’s characteristics | ||||

| Income - <$50K/year (vs. >$50K/year) | 1.26 (0.72, 2.20) | −0.50 (−12.81, 11.81) | 0.86 (0.58, 1.28) | 2.12 (−5.88, 10.11) |

| Satisfaction with the program | ||||

| Somewhat, or very satisfied (vs. Dissatisfied) | 12.77 (6.57, 24.84) | 22.70 (14.67, 30.73) | 8.65 (3.00, 24.92) | 6.81 (−32.68, 46.29) |

|

Perceived worth of the program By 20$/month increment |

----- |

1.01 (1.00, 1.03) |

0.77 (0.14, 1.40) |

|

With regards to perceived worth, participants in the EPC+C arm reported a higher median amount than participants in the EPC arm, both in the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, even after adjusting for satisfaction with the program (difference of $17.90, 95% CI, $7.03-$28.77) (Figure 1b and Table 2).

Parents in the EPC+C arm also had higher odds of reporting being interested in paying out of pocket than parents in the EPC arm (adjusted OR 1.53, 95% CI, 1.05–2.22) (Figure 2a and Table 2).

Figure 2:

Difference willingness to pay (a), and amount ($/month) parents were willing to pay (b), for participants in the EPC+C arm vs. EPC arm

Legend: Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Model 1: Intervention arm (REF=EPC)

Model 2: Model 1 + child age, sex, race/ethnicity, household income category

Model 3: Model 2 + baseline BMI category

Model 4: Model 3 + BMI category change

Model 5: Model 4 + perceived worth of the program

Model 6: Model 5 + satisfaction with the program

Model 7: Model 6 + order of presentation of WTP by iteration

Finally, among parents willing to pay for the program, in both the unadjusted and the fully adjusted analyses, parents in the EPC+C arm were not willing to pay a statistically significant greater amount per month, compared to parents in the EPC arm (difference of $5.77, 95% CI, $−1.50-$13.04) (Figure 2b and Table 2).

Mediators and other predictors

In the same multivariable model, we explored factors, other than the intervention arm, associated with an interest in continuing the program. Independently, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (vs. White non-Hispanic) was associated with greater interest in continuing the program (Table 2). Satisfaction with the program was a strong mediator of being interested in continuing (OR 12.77, 95% CI, 6.57–24.84) (Table 2).

For perceived worth, the age group of the child, non-Hispanic black ethnicity, and Hispanic/Latino ethnicity were significant predictors, while satisfaction emerged as a statistically significant mediator (Table 2).

Next, we examined factors influencing parents’ willingness to pay out of pocket. Again, Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (vs. White non-Hispanic), and satisfaction with the program were associated with increased odds of reporting being willing to pay out of pocket (Table 2). There was no effect of perceived worth on this outcome.

Lastly, none of the individual and family-level covariates (predictors or mediators) were associated with the amount parents were willing to pay for the program (Table 2). However, we did find that parents who were first presented with the upper bound ($100) of WTP by iteration method reported a median amount of WTP that was $22 higher (Difference of $22.19, 95% CI, $15.62-$28.76) in the open-ended format, than parents who were randomized to seeing the lower bound ($10) first. The perceived worth of the program was not a statistically significant mediator of the amount participants were willing to pay (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study of 638 participants in a pediatric weight management randomized trial we found that, at the end of the trial, a majority of parents were interested in continuing the program their child took part in but many were hesitant to pay out of pocket for it. This interest in continuing the program was slightly higher for participants in the intervention arm that included individualized coaching, a difference driven mainly by higher satisfaction with the program. Parents in the individualized coaching arm also reported higher perceived worth of the program, and were more likely to endorse WTP out-of-pocket for the program. These findings were robust to adjustment for both predictors and mediators that could influence WTP, e.g. amount of BMI change, as well as socioeconomic factors. However, the amount parents were willing to pay in the individualized coaching arm was not significantly greater than in the enhanced primary care arm.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report parental WTP to continue a weight management program for their child with overweight or obesity. Our study is concordant with, but also builds on, other reports. For example, 61.4% of parents whose children were taking part in a study on health promotion and physical activity in schools reported being willing to pay for a hypothetical weight loss program that would cut the incidence of childhood obesity and overweight by half, with a mean amount 23 euros/month.6 In this study, higher WTP was associated with having a child with obesity, being an immigrant, and higher household income.6 An adult study with a similar design to ours (evaluating WTP at the end of a clinical trial in which participants took part) found a median WTP of $45/month, and that neither the amount of weight loss nor their household income was associated with WTP.8

There is growing interest in the use of individualized support to help patients achieve their health goals. For example, patient navigators are increasingly being incorporated into patient centered medical home teams by employers or insurers to support medically complex patients.18 However, there is also interest in using individualized support for a broader population of patients to help them achieve health goals, including weight management.19, 20 In our study, parents were more interested in continuing the program if they were randomized to the individualized coaching intervention arm, a result mainly driven by a higher satisfaction. Parents in the individualized coaching intervention were also more likely to be willing to pay out-of-pocket for the program. This result is of particular importance given that currently, this type of support is not typically covered by insurance plans.

We also found a difference in WTP between racial/ethnic groups, similar to other studies,8 with parents of children of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity being more likely to report WTP for the program. While our analysis does not allow us to determine the exact reason for this difference, previous research has documented that many weight management programs are poorly adapted to minority groups, including Hispanics/Latinos.21 As such, Connect for Health, which used a family- and patient-centered approaches could have also created a program that was more responsive to the needs and preferences of the Hispanic/Latino population compared to traditional weight management programs, leading to a higher satisfaction from this segment of the population.

Our use of a sequence of models also allowed us to identify satisfaction as a major determinant of parental interest in continuing the program, and adjusting for satisfaction attenuated most of the difference between the two intervention arms. Interestingly, while satisfaction was also an important predictor of WTP, a statistically significant difference in WTP remained between the two intervention arms, even after adjusting for satisfaction. It is possible that participants in the health coach intervention understood that their program was more intensive and costly, and as such, were more likely to be willing to pay out of pocket for this extra service that was different from their usual primary care. This cannot be the only contributor however, given that controlling for perceived worth did not change the association between intervention arm and WTP. Interestingly, perceived worth did not emerge as a significant predictor of the amount parents were willing to pay out-of-pocket for the program.

Taken together, in evaluating interest to continue participating in and WTP for weight management programs, these findings show the importance of programs that are family-centered and focus on patient experience. While hypothetical treatment regimens such as those used in other studies6, 7 have found income and the perceived importance of weight loss as important determinants of WTP, our study shows that in real-life interventions, personal factors, such as satisfaction with the program, might be more important.

Our study has important strengths. First, unlike other studies in pediatrics, our study did not use hypothetical scenarios, but rather a program that parents knew would impact their child directly. We also obtained data from a very diverse sample with regards to both income and race/ethnicity, increasing the external validity of the results. Second, we were able to adjust for the order in which the WTP questions were presented. This is a strength given that previous studies have shown that the sequencing of questions can significantly influence WTP, a phenomenon known as anchoring or starting-point bias.8, 14, 15 Some participants might see the starting point as a proxy, or a suggestion, for the value of the program.15 In our case, it is not possible to determine which estimate, the one provided by those randomized to low, vs. high starting point, is closer to what people are “truly” willing to pay. At the very least, our study suggests the importance to continue randomizing participants to different starting point conditions, especially if WTP is determined by the iteration method.

Our study does present some limitations. First, we only obtained data after people had completed the trial, and not before they experienced it, as would be the case in a program offered to the public. It is unclear how different the results would be if parents were asked similar questions about a program their child was about to enter. To partially circumvent this concern, we did create sequential multivariable models, including models using only baseline predictors available at the beginning of the trial, such as sociodemographic characteristics and baseline weight, and those results did not differ significantly compared to models that also adjusted for mediators obtained at the end of the trial such as weight category change and satisfaction with the program. Second, like any study on WTP, there may be a difference between the amount parents declared they would be willing to pay, and what they would actually pay in real life. Similarly, there is a risk of social desirability bias in participants’ response to measures of interest to continue, WTP, and satisfaction. These are inherent to the method used, and we believe that our study is nevertheless an important first step that will assist those who are considering offering a childhood obesity management program in which parents would pay some or all of the cost of ongoing services.

Conclusion

Most parents of children participating in a weight management trial were interested in continuing the program after one year, but many were hesitant to pay out of pocket for it. Participants who received individualized coaching were more likely to endorse willingness to pay out of pocket for continuing the program than parents of children in an enhanced primary care intervention. Cost sharing may be a barrier to families interested in participating in a pediatric weight management program.

What’s new:

Over a third of parents of overweight children were willing to pay for weight management programs, and the proportion was higher for program that included individualized coaching.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the providers and staff at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates for their ongoing collaboration in pediatric obesity research efforts. We would like to thank the Connect for Health clinical research coordinators and health coaches for their assistance with the study. We thank the parents and children who serve on our advisory boards and offered their input to help shape the intervention. And lastly, we thank our community partners, Cooking Matters and multiple Massachusetts YMCAs, for making their resources available to study participants.

Financial support for this study was provided in part by an award IH-1304-6739 from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr Drouin was also supported by a Professional Postgraduate Training in Research (Fellowship) Training Award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (O.D.). Dr Taveras was also supported by K24 grant DK10589 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sharifi was supported by grants K08HS024332 and K12HS022986 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report. The information, views, and opinions contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of these organizations.

Abbreviations:

- BMI

Body mass index

- EPC

enhanced primary care

- EPC+C

EPC plus individualized coaching

- IQR

Interquartile range

- WTP

Willingness to pay

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure Statement: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article to disclose

A portion of the results has been presented as a platform presentation at the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research 2017 Meeting.

References

- 1.Sim LA, Lebow J, Wang Z, Koball A, Murad MH. Brief Primary Care Obesity Interventions: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016;138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Barlow SE, Expert C. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics 2007;120 Suppl 4:S164–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunstein CR. Willingness to pay vs. welfare. Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev 2007;1:303. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien B, Gafni A. When do the “dollars” make sense? Toward a conceptual framework for contingent valuation studies in health care. Med Decis Making 1996;16:288–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosworth R, Cameron TA, DeShazo J. Willingness to pay for public health policies to treat illnesses. Journal of health economics 2015;39:74–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kesztyus D, Lauer R, Schreiber AC, Kesztyus T, Kilian R, Steinacker JM. Parents’ willingness to pay for the prevention of childhood overweight and obesity. Health Econ Rev 2014;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawley J Contingent valuation analysis of willingness to pay to reduce childhood obesity. Economics & Human Biology 2008;6:281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerome GJ, Alavi R, Daumit GL, et al. Willingness to pay for continued delivery of a lifestyle-based weight loss program: The Hopkins POWER trial. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23:282–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu JT, Tsou MW, Hammitt JK. Willingness to pay for weight-control treatment. Health Policy 2009;91:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narbro K, Sjostrom L. Willingness to pay for obesity treatment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2000;16:50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taveras EM, Marshall R, Sharifi M, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Clinical-Community Childhood Obesity Interventions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr 2017:e171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Taveras EM, Marshall R, Sharifi M, et al. Connect for Health: Design of a clinical-community childhood obesity intervention testing best practices of positive outliers. Contemp Clin Trials 2015;45:287–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whynes DK, Frew E, Wolstenholme JL. A comparison of two methods for eliciting contingent valuations of colorectal cancer screening. J Health Econ 2003;22:555–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frew EJ, Wolstenholme JL, Whynes DK. Comparing willingness-to-pay: bidding game format versus open-ended and payment scale formats. Health Policy 2004;68:289–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahneman D Thinking, fast and slow: Macmillan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 Through 2013–2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292–2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index-for-age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ali-Faisal SF, Colella TJ, Medina-Jaudes N, Benz Scott L. The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:436–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ammentorp J, Uhrenfeldt L, Angel F, Ehrensvard M, Carlsen EB, Kofoed PE. Can life coaching improve health outcomes?--A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olsen JM, Nesbitt BJ. Health coaching to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors: an integrative review. Am J Health Promot 2010;25:e1–e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindberg NM, Stevens VJ, Halperin RO. Weight-loss interventions for Hispanic populations: the role of culture. J Obes 2013;2013:542736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]