Abstract

Behavioral and personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) have been a topic of interest and controversy for decades, with less attention paid to alterations in normal personality structure and traits. In this investigation, core personality traits (the Big 5) and their neurobiological correlates in TLE were explored using the NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) and structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) through the Epilepsy Connectome Project (ECP). NEO-FFI scores from 67 individuals with TLE (34.6±9.5 years; 67% women) were compared to 31 healthy controls (32.8±8.9 years; 41% women) to assess differences in the Big 5 traits (agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and extraversion). Individuals with TLE showed significantly higher neuroticism, with no significant differences on the other traits. Neural correlates of neuroticism were then determined in TLE participants including cortical and subcortical volumes. Distributed reductions in cortical gray matter volumes were associated with increased neuroticism. Subcortically, hippocampal and amygdala volume were negatively associated with neuroticism. These results offer insight into alterations in the Big 5 personality traits in TLE and their brain related correlates.

Keywords: Temporal Lobe Epilepsy, personality, Big 5 traits, NEO-Five Factor Inventory

1. Introduction

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is the most common drug-resistant epilepsy, accounting for 60% of the total 3.4 million people affected by epilepsy in the United States [1]. Structures within the temporal lobes, including the hippocampus and amygdala, have been implicated in anxiety, fear conditioning, and emotional memory [2]. Thus, it is reasonable to expect people with TLE to be at higher risk for affective and psychological co-morbidities [3]. Clinically these co-morbidities often remain underdiagnosed and untreated [4] and their underlying etiology often uncertain or controversial [5].

There is a long history of interest in the relationship between epilepsy, personality and psychopathology. Over the decades, views have ranged from early beliefs that personality “deteriorated” in epilepsy, to one that epilepsy was associated with inherent behavioral abnormalities likely associated with the same underlying “constitutional predispositions” that resulted in the seizures themselves, to one that personality and behavior were no different in epilepsy compared to in the general population [6]. Most influential and long lasting, however, was the belief that abnormalities in personality and the risk of psychopathology were elevated specifically in those with TLE [7] [8], a view that had enormous influence on the field for decades.

This view of “TLE peculiarity” was reflected in reports that interictal aggression, depression, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, schizophreniform psychoses and other diagnoses were elevated in TLE and likely attributable to epilepsy-induced dysfunction in mesial temporal and associated limbic structures [6] [9]. A related view was that not only psychopathology, but a matrix of changes in non-pathological features of personality, affect and behavior were associated with TLE due to a proposed underlying neurobiological mechanism (i.e., sensory-limbic hyperconnection) [10]. These personality traits could be assessed with specially designed inventories (e.g., Bear-Fedio Inventory) completed by the patient and/or proxies [11]. Using the Bear-Fedio Inventory and related behavioral measures, some studies provided findings supportive of the notion of personality change in TLE [11]—[13]. In contrast, numerous studies failed to show specific links to personality change in TLE compared to other epilepsies [14][15] [16]. The attractiveness of this particular perspective was that TLE might provide a model to unite and understand a host of behavioral anomalies under a common neurobiological mechanism. The theory was of tremendous interest for decades, but ultimately systematic reviews were critical and not supportive of the notion of TLE specificity [17]—[19]. Lost in this debate was the pertinence of “normal personality structure”, how it might differ in epilepsy compared to healthy controls, and to what degree any observed differences might be related to features of the epilepsy (e.g., seizure frequency), its social complications (e.g., stigma), or changes in brain structure (e.g., quantitative volumetrics).

Independent of this debate, work progressed to demonstrate the so-called Big 5 personality traits [20] along with procedures for their assessment. The NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) [21] was developed to assess the core traits that included neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, openness and conscientiousness. A shortened version, the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), was subsequently developed. This 60-item questionnaire uses a five point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and is designed to address the most important general personality traits and their defining factors [20].

The Big 5 personality traits can be defined as follows:

Neuroticism: Tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, stress, depression and moodiness. Neuroticism is related to emotional instability.

Openness to experience: Characteristics of interest and willingness to try new ideas, intellectual curiosity, creative and imaginative.

Extraversion: Reflects sociability, talkativeness, and tendency to seek the company of others.

Agreeableness: Includes characteristics such as trust, kindness, generousness, interest in helping others, compassion and cooperation rather than antagonism.

Conscientiousness: Encompasses high levels of thoughtfulness, self-discipline, goal-directed behaviors, organization and preference for planned, rather than spontaneous events.

To our knowledge, only three studies have examined the status of the Big 5 traits in people with epilepsy [17], [22], [23]. Locke and colleagues [22] evaluated differences in NEO-PI scores and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) between individuals with TLE and extratemporal epilepsy, and between left-and right-TLE. No significant differences were observed for any of the pairwise comparisons. Cragar et al. [23] administered the same tests to participants with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. They observed three clusters of personality: (1) very high neuroticism, low extraversion, low openness, high agreeableness, average conscientiousness; (2) average across all domains; and (3) very high neuroticism, average extraversion, low openness, low agreeableness and average conscientiousness. The third study by Swinkels and colleagues [17] compared participants with TLE to those with extra-temporal epilepsy and found no differences. However, differences in the Big 5 traits between TLE and healthy controls, and their neuroanatomical correlates, have not been examined and are the subject of this investigation.

Lastly, while earlier views of the etiology of personality change in TLE focused predominantly on mesial structures including hippocampus and amygdala, recent studies have demonstrated evidence for structural abnormalities in TLE that extend outside the mesial temporal lobes, both ipsi- and contralaterally. Bilateral cortical thinning has been observed in people with mesial TLE in the frontal, temporal, parietal [24] and occipital regions [25], and in precentral gyrus [26]. A review of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) investigations showed 26 regions to be significantly reduced in volume in TLE, with asymmetrical distribution of temporal lobe abnormalities with preference towards the ipsilateral hemisphere, and bilateral distribution of extratemporal lobe atrophy [27]. Structural abnormalities have also been observed for subcortical extratemporal regions such as bilateral thalamus and the cerebellum [28], and in white matter tracts outside the temporal lobes [29], [30]. It is possible and even likely that structural abnormalities in both temporal and extratemporal regions contribute to the development of personality changes in TLE. To test this, we performed a whole-brain exploratory study of the neural correlates of personality traits.

Specifically, we examined the Big 5 traits in participants from the Epilepsy Connectome Project (ECP), a multi-site study dedicated to developing the first large epilepsy connectome database including neuroimaging, cognitive and behavioral data. We first determined differences in core personality traits between individuals with TLE and healthy controls. In participants with TLE, we then identified neuroanatomical correlates of the significantly different personality trait using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The ECP is a multi-site research project involving the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) and the University of Wisconsin-Madison (UW-Madison). Participants with TLE enrolled in the ECP are between the ages of 18 and 60 (inclusive), demonstrate estimated full-scale IQ at or above 70, speak English fluently, and have no medical contraindications to MRI. Participants have a diagnosis of TLE supported by 2 or more of the following: 1) described or observed clinical semiology consistent with seizures of temporal lobe origin, 2) EEG evidence of either Temporal Intermittent Rhythmic Delta Activity or temporal lobe epileptiform discharges, 3) temporal lobe onset of seizures captured on continuous EEG, or 4) MRI evidence of mesial temporal sclerosis or hippocampal atrophy. Participants with TLE with any of the following are excluded: 1) presence of any lesions other than mesial temporal sclerosis, incidental benign lesions not thought to be causative for seizures, or non-specific white matter abnormalities on 3 Tesla MRI; or 2) an active infectious/autoimmune/inflammatory etiology of seizures, either suspected by treating clinicians or documented through laboratory testing or response to immunosuppressive therapy.

Healthy controls underwent cognitive and behavioral assessment, and a limited number underwent neuroimaging including MRI. No control MRI data are used in the current analyses. Control participants were between the ages of 18 and 60 (inclusive). Exclusion criteria included: 1) Edinburgh Laterality (handedness) Quotient less than +50; 2) primary language other than English; 3) history of any learning disability; 4)history of brain injury or illness, substance abuse, or major psychiatric illness (major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia); and 5) current use of psychoactive or vasoactive medications. Presented here are data from a consecutive series of 67 individuals with TLE and 31 healthy controls. This project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at MCW, and all participants provided written informed consent. Table 1 provides demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Subjects over 50 years of age were excluded from this analysis in order to match groups for age. The full neuropsychological test battery is offered to controls at only one of the two centers, contributing to the lower number of controls participating in this study. Statistical significance was found for differences in gender distribution (Chi square= 4.8, df=1, p=0.03) and subsequent analyses were corrected for gender.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics.

| Controls | TLE | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 31 | 67 | n/a |

| Age (years±SD) | 32.8±8.9 | 34.6±9.5 | 0.4 |

| Gender (% Women) | 41% | 67% | 0.03 |

| Mean Age of Onset (years±SD) | n/a | 20.1±11.2 | n/a |

| Mean Epilepsy Duration (years±SD) | n/a | 14.7±11.6 | n/a |

| Seizure focus (%) | |||

| Right | 29% | ||

| Left | n/a | 50% | n/a |

| Bilateral | 6% | ||

| Uncertain | 15% | ||

2.2. Behavioral testing

Participants in the ECP completed a battery of cognitive and behavioral tests comprising measures drawn from the Human Connectome Project (HCP) protocol. Included were tests from the NIH-Toolbox (NIHT) supplemented by measures primarily from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Common Data Elements for Epilepsy (CDE). For this investigation, participants completed the self-report, 60-item NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), which yielded scores on the Big 5 personality traits including openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Reported internal consistencies for the NEO-FFI (60 item version) include: Neuroticism = .79, Extraversion = .79, Openness = .80, Agreeableness = .75, Conscientiousness = .83. The psychometric properties of the NEO scales have been found to generalize across ages, cultures, and methods of measurement [31], and the Big 5 personality traits have been reported to remain stable among adults over time [32]

2.3. Magnetic resonance imaging

High-resolution T1-weighted (T1w) structural images were acquired on GE MR 750 3T scanners with Nova 32-channel head coils, using a 0.8mm isotropic GE “BRAVO” pulse sequence. High - resolution T2-weighted (T2w) structural images were acquired using a 3D fast spin-echo (CUBE) sequence (TR = 2500 ms, TE = 94.398 ms, flip angle = 90°, FOV = 25.6 cm, 0.8 mm isotropic). Scans were performed at UW-Madison and MCW.

2.4. Image analyses

All structural images were pre-processed using the Human Connectome Project (HCP) pipelines as described in Glasser et al. [33]. Briefly, image pre-processing is based on three main steps: PreFreeSurfer, FreeSurfer, and PostFreeSnrfer. During the PreFreeSurfer pipeline, T1w and T2w images are aligned, a native space is produced for each participant and registered to MNI space, and bias field is corrected. During the FreeSurfer pipeline the subcortical volumes are segmented into predefined structures, cortical surfaces undergo reconstruction, cortical and subcortical structures are segmented, and the morphometric measure cortical volume is computed. The cortical gray matter ribbon volume is then projected onto the reconstructed surface mesh defining the cortical surface. Finally, PostFreeSurfer produces the NIFTI volumes and GIFTI surface files that are used for visual quality inspection. Subcortical gray matter volumes were extracted using FreeSurfer’s aseg stats.

Neuroanatomical correlations of neuroticism were determined in participants with TLE. Freesurfer’s QDEC [34] was used to perform surface-based analysis for cortical volume measurements. Each subject’s native surface measures were mapped to the atlas surface of “fsaverage” to allow between-subject comparisons. Surface data were smoothed with a 10-mm full-width half max (FWHM) filter. The following measures were added as covariates: gender, age, total intracranial volume (ICV), and laterality of seizure focus. To correct for multiple comparisons of cortical surface volume, a Monte Carlo simulation was implemented with a cluster-forming threshold set to p < 0.01. Clusters were tested against an empirical null distribution of maximum cluster size built using synthesized Z distributed data across 10,000 permutations, producing cluster wise p-values fully corrected for multiple comparisons.

Subcortical regions of interest included the thalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, putamen, caudate and cerebellum using the same covariates (age, gender, ICV, lateralization of EEG focus). Two TLE subjects were excluded from the analysis of cortical gray matter volume correlations because of missing structural data, and eight were excluded for missing information leaving a final TLE sample of 57 participants (age=34.4±9.5, percent women=63%).

2.5. Other statistical analyses

Three additional sets of analyses were performed. First, using the R [35] statistical software package, MANCOVA examined overall group performance (TLE versus controls) across the 5 NEO-FFI personality traits controlling for gender and age, with post-hoc ANCOVA used to determine group differences across each Big 5 trait. Second, partial correlations examined associations between personality traits and selected clinical epilepsy factors (age of onset, epilepsy duration/chronicity) controlling for gender and age. These analyses were limited to traits that differed between TLE and controls as identified in the analysis described above. Third, because our distribution was skewed towards more women, we performed cortical correlation analysis for neuroticism only in women to determine if core findings were still present.

3. Results

3.1. NEO group comparisons

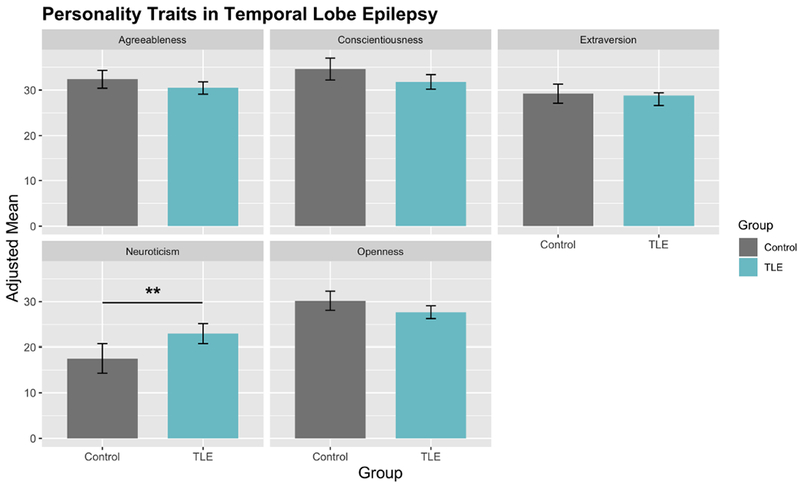

MANCOVA revealed a significant difference between groups for all traits (F=3.01, p=0.01, df=5). Post-hoc ANCOVAs to determine differences across each Big 5 trait revealed significantly higher neuroticism (p=0.002) in TLE. Individuals with TLE also showed lower but not significantly abnormal agreeableness (p=0.14), conscientiousness (p=0.08), extraversion (p=0.22) and openness (p=0.10) (Figure 1, Table 2). Supplementary Table 1 presents details of the ANCOVAs.

Figure 1. NEO test scores comparison between controls and TLE.

Neuroticism was significantly higher in individuals with TLE. Agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion and openness were lower, but not significant different in TLE compared to controls.

Table 2.

ANCOVA results for NEO-FFI scales comparing TLE to control participants.

| Trait | Group | Mean | SE | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Control | 32.4 | 0.997 | 2.197 | 0.14 |

| TLE | 30.5 | 0.671 | |||

| Openness | Control | 30.2 | 1.056 | 2.817 | 0.1 |

| TLE | 27.7 | 0.711 | |||

| Conscientiousness | Control | 34.6 | 1.198 | 3.045 | 0.08 |

| TLE | 31.8 | 0.806 | |||

| Neuroticism | Control | 17.5 | 1.63 | 10.346 | 0.002** |

| TLE | 23.0 | 1.09 | |||

| Extraversion | Control | 29.2 | 1.047 | 1.543 | 0.22 |

| TLE | 28.0 | 0.705 |

df =94.

p<0.01.

3.2. Relationship between epilepsy onset and NEO Neuroticism

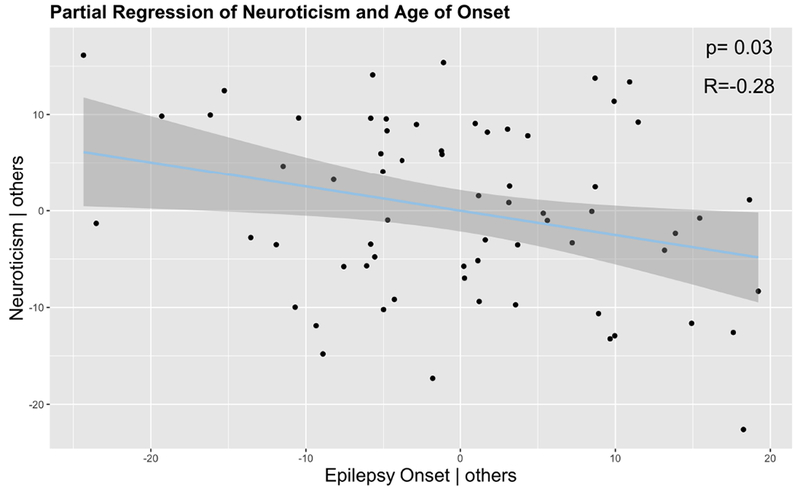

Partial correlations were performed to determine the relationships between age of epilepsy onset and epilepsy duration with neuroticism. Results revealed a significant negative correlation between neuroticism and age of epilepsy onset (r= −0.30; df=62; p=0.02), indicating higher neuroticism with earlier age of epilepsy onset (Figure 2). No significant association was observed between neuroticism and epilepsy duration (r=0.07; df=62; p=0.6).

Figure 2. Partial regression between NEO Neuroticism and age of onset.

Higher neuroticism was associated with earlier age of epilepsy onset. Others = covariates.

3.3. Cortical gray matter correlates of NEO Neuroticism in TLE

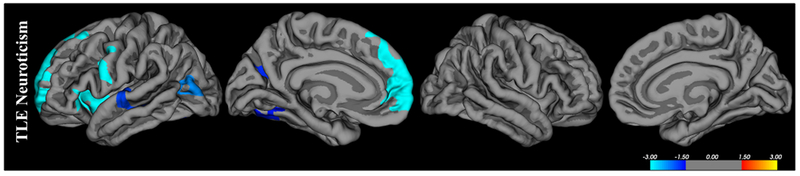

The association between cortical gray matter and neuroticism in TLE was determined using surface based volumetric analysis using FreeSurfer’s QDEC as described previously. The focus of analysis was the one personality trait (neuroticism) that was significantly different between TLE and control participants. We corrected for age, gender, ICV and laterality focus. P-values were determined with df= 43 using FreeSurfer’s default Different Onset, Different Slope (DODS) [36].

Higher neuroticism was associated with significantly lower cortical gray matter volume in the left superior frontal gyrus and rostral middle frontal cortex, anterior insula, precentral gyrus, lateral parietal-occipital cortex, superior temporal gyrus, precuneus, and fusiform gyrus (Figure 3, Table 3). Uncorrected surface images are show in Supplemental Figure 3.

Figure 3. Correlation between cortical gray matter volume and NEO Neuroticism for TLE participants.

Blue areas represent regions with significant (p<0.05) negative correlations representing decreased volume with increased neuroticism. Results were corrected using Monte-Carlo simulations with a 0.01 threshold (df=43).

Table 3.

Cortical regions associated with NEO Neuroticism scores, including corrected p value, cluster size and Talairach coordinates

| Personality trait | Group | Brain Region | Size (mm^2) | Direction | Corrected P | Tal. Cood. (x,y,z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | TLE | |||||

| Left Superior/Middle Frontal Gyrus | 2875.23 | Negative | 0.0001 | −19.3, 56.6, −3.1 | ||

| Left Anterior Insula | 1210.05 | Negative | 0.0001 | −36.2, 1.5, −6.2 | ||

| Left Precentral Gyrus | 830.02 | Negative | 0.0008 | −38.4, 0.5, 27.9 | ||

| Left Lateral Parietal-Occipital Cortex Cortex | 650.9 | Negative | 0.0054 | −41.6, −63.7, 13.1 | ||

| Left Superior Temporal Gyrus | 542.75 | Negative | 0.0172 | −60.8, −12.5, −0.2 | ||

| Left Precuneus | 507.56 | Negative | 0.0251 | −17.0, −58.1, 25.1 | ||

| Left Fusiform Gyrus | 478.77 | Negative | 0.0347 | −30.9, −57.1, −6.4 |

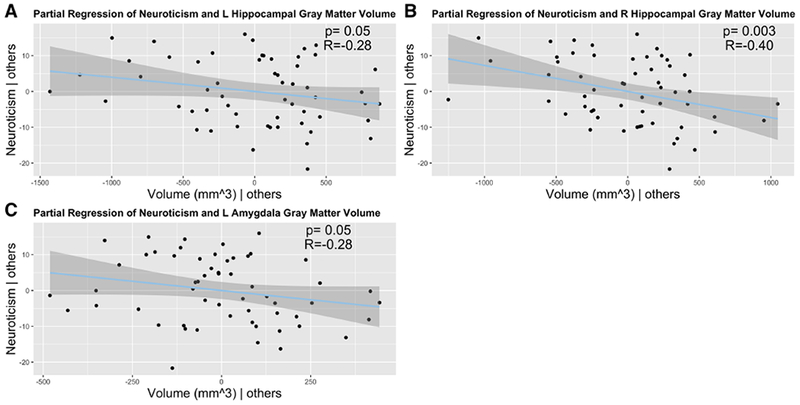

3.4. Subcortical gray matter correlates of NEO Neuroticism in TLE

ROI extraction and partial correlations correcting for age, gender, seizure focus laterality and ICV were performed to determine the relationship between selected subcortical regions and personality traits. A negative relationship was observed between the left amygdala (r=−0.28; p=0.05) and bilateral hippocampi [left (r=−0.28; p=0.05); right (r=−0.40; p=0.003)] (Figure 4). P values presented are uncorrected for multiple comparisons and calculated based on a t-distribution with df=49.

Figure 4. Partial regression between subcortical gray matter volume and neuroticism.

Lower gray matter volume was associated with increased neuroticism in the (A) left and (B) right hippocampus, and the (C) left amygdala. Others= covariates.

3.5. Supplemental Analyses

Given the relationship between epilepsy age of onset and neuroticism, we performed a post-hoc analysis to characterize the relationship between age of onset of epilepsy and cortical gray matter volume. Supplemental Figure 1 shows that the association of cortical volume and age of onset revealed limited and nonoverlapping areas of abnormality compared to that shown in the relationship of neuroticism with cortical volume (Figure 3).

Because we had a significantly higher number of women compared to men, we performed cortical correlation analysis for neuroticism in women only. This analysis was also corrected for age, ICV and seizure focus laterality. Supplemental Figure 2 shows areas such as the left frontal and precentral cortex hold for women with TLE at p=0.05. Right inferior parietal and caudal middle frontal were also found to be correlated with neuroticism in women.

4. Discussion

The core findings from this investigation include the following: 1) there are differences in aspects of normal (Big 5) personality structure identified in people with TLE compared to controls, 2) a link is identified between selected clinical characteristics of the patients’ epilepsy and personality, and 3) alterations in aspects of brain structure are associated with core personality traits in TLE. These points will be discussed below.

4.1. Personality measures

The Big 5 personality traits have been investigated in relation to several diseases [37]—[39] and cognitive processes [40]. However, there is scarce information regarding the Big 5 traits in people with TLE. As reviewed previously, a variety of behavioral, personality and affective disorders in individuals with epilepsy have been a long standing topic of investigation and controversy [18]. In contrast, there has been considerably less research into how normal personality features may be affected in TLE. The present study used the NEO-FFI as a tool to assess normal core (Big 5) personality traits in individuals with TLE compared to healthy controls. These core traits include agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and extraversion.

The omnibus MANCOVA demonstrated a significant difference between TLE and healthy controls across the Big 5 personality traits. Post-hoc ANCOVA examined differences between groups across each specific personality trait, revealing significantly elevated neuroticism in TLE. This significant difference, and the trends observed in agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness and extraversion (lowered in TLE), likely drove the statistical difference between groups observed with the MANCOVA.

The trait neuroticism encompasses feelings of anxiety, depression, self-doubt, irritability, and other negative emotional responses. These states are highly correlated but partially distinct [41]. While not examining all 5 core traits, higher levels of neuroticism in TLE has been shown before [42] using the Fragebo-gen zur Persönlichkeit bei zerebralen Erkrankungen (FPZ), a clinical personality questionnaire. In addition, Margolis et al. showed that higher neuroticism as well as reduced extraversion in people with epilepsy (measured with the NEO-FFI) was significantly correlated with greater perceived stigma [43]. Furthermore, stigma was significantly associated with poorer social well-being.

Neuroticism has been identified as a predictor of depression [44], a risk factor for behavioral dysregulation [45], and has been negatively associated with measures of well-being [46]. Suicide ideation, hopelessness, and depressive symptoms have been predicted by neuroticism, or neuroticism facets such as depression, anger, and hostility [47]. Persons high in neuroticism also tend to prospectively report more negative life events, although not significantly fewer positive events [48]. This highlights the importance of identifying alterations in normal personality traits in patients with TLE, particularly neuroticism, in order to address them through interventions.

Regarding the association of neuroticism with targeted clinical seizure features, we found that earlier age of epilepsy onset, but not epilepsy duration, was associated with increased neuroticism. An association between epilepsy onset during adolescence and elevated neuroticism has been reported by Wilson et al. [49]. Consistent with early reports [50], no relationship was found between the degree of neuroticism and duration of epilepsy.

4.2. Neuroanatomical correlations with NEO personality traits

Little is known about the relationship between gray matter volume and personality as assessed by the Big 5 traits in patients in TLE. More generally, previous research has identified neuroanatomical correlates of the Big 5 personality traits in healthy individuals [51]–[53]. Through this research, we aimed to understand the neuroanatomical correlates of personality in TLE and used structural MRI to examine associations of neuroticism with cortical and subcortical volumes.

All the identified significant associations between neuroticism and gray matter volume showed higher levels of neuroticism to be related to decreased gray matter volume, this inverse relationship was observed only in the left hemisphere for cortical regions that spanned the following regions: rostral superior and middle frontal gyri, precentral gyrus, anterior insula, superior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, precuneus, and lateral parietal-occipital cortex. Our analyses controlled for a number of factors (age, gender, ICV, and laterality of EEG focus), so the obtained findings speak to the general anatomical correlates of neuroticism. These findings suggest that a unitary etiology limited to a focus in the mesial temporal lobe is too limited a view, and that regions involving but especially outside the temporal lobe contribute to alterations in selected core personality traits.

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays a role in the central circuitry of emotion [54]. Normal emotional and social behavior depends on the integrity of brain regions including the orbitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex (medial aspect of the superior frontal gyrus) and the amygdala [55]. Neural correlates of neuroticism in healthy individuals have shown an inverse relationship between neuroticism and volume in the superior and middle frontal gyri [56]. In TLE, previous studies have shown a relationship between dysphoric mood state and frontal lobe dysfunction [57]. The PFC has been linked with executive and cognitive dysfunction in TLE [58]. Our results suggest that the medial and dorsal PFC also plays a role in abnormal personality traits, neuroticism in particular.

We also found a negative association between neuroticism and the left superior temporal gyrus and anterior insula in people with TLE. Our observation of an inverse relationship between neuroticism and volume of the superior temporal gyrus mirrors the results of previous studies performed in healthy individuals [59]. Functional MRI studies have also shown a relationship between neuroticism or anxiety and volume of the insula [60]–[63]

We observed a significant laterality effect in the volumetric reductions, with most involving the left hemisphere. Considerable research in the field of affective asymmetry suggests that the left and right hemispheres play different roles in emotions. The right hemisphere has been associated with negative emotions and the left hemisphere with positive emotions [64]. Many clinical studies have shown that damage to the left hemisphere results in depressive-like symptoms [65], [66]. More specifically, the closer the lesion is to the frontal pole, the more severe the depressive symptoms [64]. The data presented here in relationship to neuroticism are consistent with the general theme reported in the clinical affective asymmetry literature. ROI-based subcortical volumes were associated with neuroticism in TLE as well. Decreased bilateral hippocampal and left amygdala volume was related to higher neuroticism. Our findings therefore suggest that both cortical and subcortical regions play a role in altered core personality traits in epilepsy.

Regarding clinical epilepsy factors, gray matter volume reductions have been reported to be associated with epilepsy age of onset [67], and we observed a relationship between neuroticism and earlier epilepsy age of onset. However, we demonstrated that the effects of age of onset on cortical gray matter volume did not overlap with the effects reported in relation to neuroticism (Figure 3 and Supplemental Figure 1).

Overall, these results suggest widespread associations between brain volume and neuroticism in TLE. As previously mentioned, TLE has been shown to affect temporal and extratemporal brain regions including some of the structures that correlate with neuroticism in our results. Our results highlight neuroticism as a factor impacting individuals with TLE. While there is a vast literature on the relationship between personality traits and brain structure in healthy individuals, much is unknown in relation to neurological disorders. More specifically, we believe this is the first study to evaluate this comprehensively in TLE.

4.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this study uses data form the Epilepsy Connectome Project, but the presented analyses did not involve connection calculations or network data. We will pursue this aspect of the data in the future. Second, we had a modest control group sample size which could have served to limit our power to detect additional alterations in the Big 5 traits. Additional research with larger sample sizes may reveal additional differences in Big 5 characteristics between controls and patients with TLE. Third, our sample was skewed towards women, and the presence of potential gender effects is an important issue for the future. Fourth, no comparisons were made to other types of epilepsy and we cannot conclude that the results presented are specifically linked to seizures originating from the temporal lobes. Fifth, the potential impact of anti-epilepsy medications on cognitive and behavioral measures is always a concern, but one that is difficult to address reliably in a cross-sectional observational investigation. Sixth, we did not investigate variability in Big 5 traits as a function of the laterality of TLE onset. Only a subset of our participants underwent ictal monitoring, and this is a potentially important topic for future studies. We did, however, use laterality of seizure focus (determined largely by interictal EEG) as a covariate. Lastly, it is important to keep in mind that we cannot infer causation from the present results, however, they provide insight into structural changes that could play a role in personality disorders in people with TLE.

Taken together, these results suggest differences in personality traits, particularly neuroticism in TLE. Additionally, we show neuroanatomical correlates of personality traits that could shed light in our understanding on the neuroscience of personality.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Individuals with Temporal Lobe Epilepsy (TLE) show higher levels of neuroticism as measured with the NEO-Five Factor Inventory.

Higher neuroticism is associated with earlier age of epilepsy onset.

Distributed reductions in cortical gray matter volumes were associated with increased neuroticism in TLE.

Hippocampal and amygdala volume were negatively associated with neuroticism in TLE.

6. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants and their families. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Taylor McMillan for recruitment and participant acquisition, MRI technologists and other support staff. Funding for healthy control subjects’ data acquisition was provided in part by the Department of Radiology at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. This study was supported by grant number U01NS093650 from the National Health Institute. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32MH018931. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Prior to issuing a press release concerning the outcome of this research, please notify the National Institutes of Health awarding IC in advance to allow for coordination.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Zack R, Matthew M, Kobau, “National and State Estimates of the Numbers of Adults and Children with Active Epilepsy — United States, 2015,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. [Online], Available: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6631a1.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [2].Rajmohan V and Mohandas E, “The limbic system,” Indian J Psychiatry, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 132–139, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kandratavicius L, Ruggiero RN, Hallak JE, Garcia-Cairasco N, and Leite JP, “Pathophysiology of mood disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy,” Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr, vol. 34, no. SUPPL2, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boylan LS, Flint LA, Labovitz DL, Jackson SC, Stamer K, and Devinsky O, “Depression but not seizure frequency predicts quality of life in treatment-resistant epilepsy,” Neurology, vol. 62, no. 2, p. 258 LP–261, January 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gilliam FG, Santos J, Vahle V, Carter J, Brown K, and Hecimovic H, “Depression in Epilepsy: Ignoring Clinical Expression of Neuronal Network Dysfunction?,” Epilepsia, vol. 45, no. s2, pp. 28–33, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Guerrant J, Anderson WW, Fischer A, Weinstein MR, Jaros RM, and Deskins A, Personality in epilepsy. Springfield, IL, US: Charles C Thomas Publisher, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gibbs EL, Gibbs FA, and Fuster B, “Psychomotor epilepsy.,” Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 331–339, October 1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gibbs FA and Gibbs EL, “Psychiatric implications of discharging temporal lobe lesions.,” Trans. Am. Neurol. Assoc, vol. 73, no. 73 Annual Meet., pp. 133–137, 1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tizard B, “The personality of epileptics: A discussion of the evidence.,” Psychol. Bull, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 196–210, 1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bear D, “Temporal Lobe Epilepsy - A Syndrome Of Sensory-Limbic Hyperconnection,” Cortex, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 357–384, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].DM B and Fedio P, “Quantitative analysis of interictal behavior in temporal lobe epilepsy,” Arch. Neurol, vol. 34, no. 8, pp. 454–467, August 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Waxman SG and Geschwind N, “The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy.,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 1580–1586, December 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Geschwind N, “Behavioral Change in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy,” Arch Neurol, vol. 34, p. 453, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rodin E and Schmaltz S, “The Bear-Fedio personality inventory and temporal lobe epilepsy.,” Neurology, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 591–596, May 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tremont G et al. , “Comparison of personality characteristics on the bear-fedio inventory between patients with epilepsy and those with non-epileptic seizures.,” J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 47–52, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mungas D, “Interictal behavior abnormality in temporal lobe epilepsy. A specific syndrome or nonspecific psychopathology?,” Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 108–111, January 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Swinkels WAM, Van Emde Boas W, Kuyk J, Van Dyck R, and Spinhoven P, “Interictal depression, anxiety, personality traits, and psychological dissociation in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) and extra-TLE,” Epilepsia, vol. 47, no. 12, pp. 2092–2103, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Turnbull C, Jones S, Adams SJ, and Velakoulis D, “Epilepsy and personality,” in Epilepsy and the Interictal State: Co-morbidities and Quality of Lif Wiley, 2015, pp. 171–182. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bowden SC, Simpson LC, and Cook MJ, “Neuropsychological Aspects of Temporal-Lobe Epilepsy: Seeking Evidence-Based Practice,” in Neuropsychological Formulation: A Clinical Casebook J. A. B. Macniven Ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp. 71–88. [Google Scholar]

- [20].McCrae RR and Costa PT Jr., “The Five-Factor Theory of Personality,” in Handbook of Personality, Third Edition: Theory and Research, Guilford Press, 2008, pp. 159–181. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Costa PT and McCrae RR, “Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory.,” Psychol. Assess, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 5–13, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Locke DEC, Fakhoury TA, Berry DTR, Locke TR, and Schmitt FA, “Objective evaluation of personality and psychopathology in temporal lobe versus extratemporal lobe epilepsy,” Epilepsy Behav, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 172–177, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cragar DE, Berry DTR, Schmitt FA, and Fakhoury TA, “Cluster analysis of normal personality traits in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures,” Epilepsy Behav, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 593–600, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kemmotsu N et al. , “MRI analysis in temporal lobe epilepsy : Cortical thinning and white matter disruptions are related to side of seizure onset,” Epilepsia, vol. 52, no. 12, pp. 2257–2266, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lin JJ et al. , “Reduced neocortical thickness and complexity mapped in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis.,” Cereb. Cortex, vol. 17, no. 9, pp. 2007–2018, September 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].McDonald CR et al. , “Regional neocortical thinning in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy.,” Epilepsia, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 794–803, May 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Keller SS and Roberts N, “Voxel-based morphometry of temporal lobe epilepsy: An introduction and review of the literature,” Epilepsia, vol. 49, no. 5, pp. 741–757, February 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].McDonald CR et al. , “Subcortical and cerebellar atrophy in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy revealed by automatic segmentation.,” Epilepsy Res, vol. 79, no. 2–3, pp. 130–138, May 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rodriguez-Cruces R and Concha L, “White matter in temporal lobe epilepsy: clinico-pathological correlates of water diffusion abnormalities.,” Ouant. Imaging Med. Surg, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 264–278, April 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gross DW, “Diffusion tensor imaging in temporal lobe epilepsy.,” Epilepsia, vol. 52 Suppl 4, pp. 32–34, July 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Costa PT and Mccrae RR, “NEO ™ Personality Inventory-3,” vol. 3, pp. 287–307, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cobb-Clark DA and Schurer S, “The stability of big-five personality traits,” Econ. Lett, vol. 115, no. 1, pp. 11–15,2012. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Glasser MF et al. , “The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project,” Neuroimage, vol. 80, pp. 105–124, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].“QDEC,” 2015. [Online], Available: www.surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu. [Accessed: 21-Nov-2018],

- [35].R Core Team, “R: A language and environment for statistical computing,” 2017. [Online], Avail able: https://www.r-project.org.

- [36].Greve D, “DodsDoss,” FreeSurferWiki, 2018. [Online], Available: https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/fswiki/DodsDoss.

- [37].Lykou E et al. , “Big 5 personality changes in Greek bvFTD, AD, and MCI patients,” Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 258–264, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Camisa KM, Bockbrader MA, Lysaker P, Rae LL, Brenner CA, and Donnell BFO, “Personality traits in schizophrenia and related personality disorders,” vol. 133, pp. 23–33, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kersh BC et al. , “Psychosocial and health status variables independently predict health care seeking in fibromyalgia.,” Arthritis Rheum, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 362–371, August 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Curtis RG, Windsor TD, and Soubelet A, “The relationship between Big-5 personality traits and cognitive ability in older adults - a review,” Aging, Neuropsychol. Cogn., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 42–71, January 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Lahey BB, “NM Public Access,” vol. 64, no. 4, pp. 241–256, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Helmstaedter C and Witt JA, “Multifactorial etiology of interictal behavior in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsy,” Epilepsia, vol. 53, no. 10, pp. 1765–1773, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Margolis SA, Nakhutina L, Schaffer SG, Grant AC, and Gonzalez JS, “Perceived epilepsy stigma mediates relationships between personality and social well-being in a diverse epilepsy population,” Epilepsy Behav, vol. 78, pp. 7–13, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dunkley DM, Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, and Mcglashan TH, “Self-criticism versus neuroticism in predicting depression and psychosocial impairment for 4 years in a clinical sample,” Compr. Psychiatry, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 335–346, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fetterman AK, Robinson MD, Ode S, and Gordon KH, “Neuroticism as a Risk Factor for Behavioral Dysregulation : A Mindfulness-Mediation Perspective,” vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 301–321,2010. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Costa PT, Mccrae RR, and Norris AH, “Personal Adjustment to Aging : Longitudinal Prediction from Neuroticism and Extraversion,” vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 78–85, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chioqueta AP and Stiles TC, “Personality traits and the development of depression , hopelessness , and suicide ideation,” vol. 38, pp. 1283–1291, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Magnus K, Diener E, Fujita F, and Pavot W, “Extraversion and Neuroticism as Predictors of Objective Life Events : A Longitudinal Analysis,” vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 1046–1053, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wilson S, Jrench J, McIntosh A, Bladin P, and Berkovic S, “Personality development in the context of intractable epilepsy,” Arch. Neurol, vol. 66, no. 1, pp. 68–72, January 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Eysenck MD, “Neurotic Tendencies in Epilepsy,” J. Neurol neurosurgPsychiat, vol. 13, pp. 237–240, 1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Gray JR, Papademetris X, Hirsh JB, Rajeevan N, DeYoung CG, and Shane MS, “Testing Predictions From Personality Neuroscience,” Psychol. Sci, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 820–828, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wright CI. et al. , “Neuroanatomical correlates of extraversion and neuroticism,” Cereb. Cortex, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 1809–1819, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lu F et al. , “Relationship between Personality and Gray Matter Volume in Healthy Young Adults : A Voxel-Based Morphometric Study,” vol. i, no. 2, pp. 1–8, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Romano A et al. , “Pre-surgical planning and MR-tractography utility in brain tumour resection,” Eur. Radiol, vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 2798–2808, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Drevets WC, “Orbitofrontal cortex function and structure in depression,” Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci, vol. 1121, pp. 499–527, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].DeYoung CG, Hirsh JB, Shane MS, Papademetris X, Rajeevan N, and Gray JR, “Testing predictions from personality neuroscience. Brain structure and the big five.,” Psychol. Sci. a J. Am. Psychol. Soc. / APS, vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 820–828, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hermann BP, Seidenberg M, Haltinerr A, and Wyler AR, “Mood state in unilateral temporal lobe epilepsy,” Biol. Psychiatry, vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1205–1218, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Stretton J and Thompson PJ, “Frontal lobe function in temporal lobe epilepsy,” Epilepsy Res, vol. 98, no. 1, pp. 1–13, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Riccelli R, Toschi N, Nigro S, Terracciano A, and Passamonti L, “Surface-based morphometry reveals the neuroanatomical basis of the five-factor model of personality,” Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 671–684, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Coen SJ et al. , “Neuroticism influences brain activity during the experience of visceral pain,” Gastroenterology, vol. 141, no. 3, p. 909–917.el, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Paulus MP and Stein MB, “An Insular View of Anxiety,” Biol. Psychiatry, vol. 60, no 4, pp. 383–387, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Terasawa Y, Shibata M, Moriguchi Y, and Umeda S, “Anterior insular cortex mediates bodily sensibility and social anxiety,” Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 259–266, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Feinstein JS, Stein MB, and Paulus MP, “Anterior insula reactivity during certain decisions is associated with neuroticism,” Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 136–142, September 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Davidson RJ, “Emotion and Affective Style: Hemispheric Substrates,” Psychol. Sci, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 39–43, January 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Gainotti G, “Emotional behavior and hemispheric side of the lesion.,” Cortex, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 41–55, March 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Sackeim HA, Greenberg MS, Weiman AL, Gur RC, Hungerbuhler JP, andGeschwind N, “Hemispheric asymmetry in the expression of positive and negative emotions Neurologic evidence.,” Arch. Neurol, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 210–218, April 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kim JS, Koo DL, Joo EY, Kim ST, Seo DW, and Hong SB, “Asymmetric Gray Matter Volume Changes Associated with Epilepsy Duration and Seizure Frequency in Temporal-Lobe-Epilepsy Patients with Favorable Surgical Outcome,” J Clin Neurol, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 323–331, July 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.