Abstract

Background:

Pelvic floor myofascial pain, which is predominantly identified in the muscles of the levator ani and obturator internus, has been observed in women with chronic pelvic pain and other pelvic floor disorder symptoms, and is hypothesized to contribute to their symptoms.

Objectives:

To describe the prevalence of pelvic floor myofascial pain in patients presenting with pelvic floor disorder symptoms and to investigate whether severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain on examination correlates with degree of pelvic floor disorder symptom bother.

Study Design:

All new patients seen at one tertiary referral center between 2014 and 2016 were included in this retrospectively-assembled cross-sectional study. Pelvic floor myofascial pain was determined by transvaginal palpation of the bilateral obturator internus and levator ani muscles, and scored as a discrete number on an 11-point verbal pain rating scale (range 0–10) at each site. Scores were categorized as none (0), mild (1–3/10), moderate (4–6/10), and severe (7–10/10) for each site. Pelvic floor disorder symptom bother was assessed by the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory short form (PFDI-20) scores. The correlation between these two measures was calculated using Spearman’s rank and partial rank correlation coefficients

Results:

912 new patients were evaluated. After excluding 79 with an acute urinary tract infection, 833 patients were included in the final analysis. Pelvic floor myofascial pain (pain rated >0 in any muscle group) was identified in 85.0% of patients: 50.4% rated as severe, 25.0% moderate, and 9.6% mild. In unadjusted analyses and those adjusted for postmenopausal status, severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain was significantly correlated with subjective prolapse symptoms such as pelvic pressure and heaviness but not with objective prolapse symptoms (seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge or having to push up on a bulge to start or complete urination) or leading edge. Severity of myofascial pain at several individual pelvic floor sites was also independently correlated with lower urinary tract symptoms, including pain in the lower abdomen (myofascial pain at all sites) and difficulty emptying the bladder (right obturator internus and left levator ani); and with defecatory dysfunction, including sensation of incomplete rectal emptying (pain at all sites combined and the right obturator internus), anal incontinence to flatus (pain at all sites combined), and pain with defecation (pain at all sites combined, and the right obturator internus and left levator ani).

Conclusions:

Pelvic floor myofascial pain was common in patients seeking evaluation for pelvic floor disorder symptoms. Location and severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain was significantly correlated with degree of symptom bother, even after controlling for postmenopausal status. Given the high prevalence of pelvic floor myofascial pain in these patients and correlation between pain severity and degree of symptom bother, a routine assessment for pelvic floor myofascial pain should be considered for all patients presenting for evaluation of pelvic floor symptoms.

Keywords: pelvic floor myofascial pain, pelvic floor myalgia, tension myalgia, pelvic floor disorders

Condensation:

We found that pelvic floor myofascial pain was common in patients seeking evaluation for pelvic floor disorder symptoms, and that the severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain was correlated with the degree of symptom bother.

Introduction

Myofascial pain has been identified and studied in various regions throughout the body, and is known to affect the pelvis in both men and women.1,2 Pelvic myofascial pain is predominantly identified in the internal hip (obturator internus (OI)) and pelvic floor (levator ani (LA)) muscles and is often referred to as pelvic floor myofascial pain (PFMP) or, alternatively, as levator myalgia or pelvic floor tension myalgia.2–4 Although PFMP on examination is widely recognized in female patients with pelvic pain, it has also been detected in patients without pelvic pain, and a high prevalence has been identified among patients referred to urogynecology subspecialists.2

In our urogynecology subspecialty practice, it is our clinical impression that there is a high prevalence of PFMP in patients presenting with pelvic floor symptoms including pelvic pressure, heaviness, and “irritative” voiding symptoms. We have observed these symptoms even in women with normal-range vaginal support and normal bladder function on assessment, and we suspect that they may be explained, in part, by the anatomic proximity of the pelvic floor muscles to the vagina and pelvic viscera. For instance, because of the anatomic proximity of the pelvic floor and the vagina, PFMP may actually be sensed as pressure or heaviness. This sensation may be misinterpreted as arising from the vaginal bulge when, in fact, it is arising from the pelvic floor muscles.

The anatomic proximity of the pelvic viscera to the pelvic floor muscles may also explain irritative voiding symptoms in these patients. As the bladder fills, it rests on the OI and LA muscles.5 Contact between these muscles and the full bladder may lead to stimulation of myofascial trigger/tender points, which may be misinterpreted as urinary urgency. Involuntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles has been observed with bladder filling and may contribute to the sensation of urinary urgency.6 Finally, defecatory dysfunction is commonly reported in patients with pelvic floor symptoms and may be related to underlying pelvic floor muscle dysfunction.7,8

Until very recently, these hypotheses were difficult to study because a standardized, reproducible examination for PFMP did not exist.9,10 As a result, PFMP has remained largely understudied and poorly recognized by women’s health providers who are not typically trained to consider or assess for PFMP as a contributing factor to patients’ symptoms. Therefore, to begin to shed light on this possible relationship, we took advantage of routinely collected PFMP data in our practice. Objectives of this study were to describe the prevalence of PFMP in patients presenting with pelvic floor symptoms and to investigate whether PFMP severity on examination correlates with the degree of pelvic floor symptom bother.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This retrospectively-assembled cross sectional study included new patients seen in a urogynecology subspecialty practice at one tertiary referral center from 1/2014–4/2016. All patients were eligible, except for those with evidence of an acute urinary tract infection (UTI) based on symptoms and urine culture performed at the time of initial evaluation. This exclusion was made to avoid over-inflating PFMP prevalence estimates and confounding any observed correlations between PFMP severity and pelvic floor symptom bother with UTI-related pain. Two reviewers abstracted data including demographic characteristics, chief complaint, past medical and surgical histories, Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory scores, and myofascial examination findings and entered them into a REDCap database.11 Pain was considered present if either the patient’s chief complaint included pain or if there was mention of pain in the History of Present Illness section of the clinical note. If the patient reported dyspareunia only, this was categorized as positive for dyspareunia but not pain. Categorization of the patient’s pain did not take into account what was reported on the PFDI-20 responses.

Pelvic floor myofascial pain assessment

All providers perform a systematic PFMP examination on all new patients at our institution. Patients included in this sample were examined by one of two fellowship-trained, right-handed urogynecologists at our institution who conducted the examination in a systematic, standardized way. This examination involves transvaginal palpation of the bilateral OI and LA muscles proceeding counter-clockwise starting with the right OI and ending with the left OI as previously described.10 A single digit is used to palpate each muscle once in the center of the muscle belly then sweeping along the length of the muscle in the direction of the muscle fibers. Pain is recorded as a discrete number on an 11-point verbal pain rating scale at each of the four sites. PFMP scores were categorized as none (0), mild (1–3/10), moderate (4–6/10), and severe (7–10/10) for each site. In order to standardize the pressure applied internally and to orient the patient to the internal examination, we first demonstrate the amount of pressure that will be applied by palpating a region of the mid-thigh prior to the internal examination. We do this to demonstrate to the patient that palpation of a non-injured muscle should be sensed as pressure and not pain. If this reference point is tender, we find another muscle that is not tender to demonstrate the reference pressure. Following data collection for this study, the examination protocol was formalized and modified to incorporate assessment of external sites, force was standardized, and reproducibility across four examiners was studied and found to be high.10

Pelvic floor disorder symptom bother assessment

All new patients complete the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory short form (PFDI-20) before their visit. This validated questionnaire assesses the presence of and bother from pelvic floor symptoms. It is categorized into three subscales for prolapse (Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; POPDI), urinary (Urogenital Distress Inventory; UDI), and bowel (Colorectal/Anal Distress Inventory; CRADI) symptoms.12 The short form has been shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive to change in women with pelvic floor disorders.13 Questionnaire responses were scored according to published methods.13

Statistical analysis

PFMP score distributions were examined in the full sample and stratified by pain as a presenting complaint using box plots and proportions. For the correlation analyses, potential confounding was explored by comparing demographic and clinical characteristics across categories of PFMP scores in the full sample and separately in the samples with complete information on each PFDI-20 subscale. Comparisons were made using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables as appropriate. Demographic and clinical characteristics were also compared between patients who did and did not complete each PFDI-20 subscale to inform the potential for selection bias. PFMP and PFDI-20 scores were compared and the correlation between these measures was calculated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients. Spearman’s partial rank correlation coefficients were used to adjust for variables that differed between groups defined by PFMP severity. As only postmenopausal status resulted in an appreciable change in point estimates for PFMP, only this variable was retained in the final Spearman partial rank correlation analyses. SAS version 9.4 was used for statistical analysis. The Institutional Review Board at Washington University in St. Louis approved this study.

Results

A total of 912 new patients were evaluated during the study period. Seventy-nine with an acute UTI were excluded. Chief complaints in the remaining 833 patients included urinary symptoms (n=765, 91.8%), bulge symptoms (n=253, 30.4%), dyspareunia (n=431, 51.8%), and pain (n=486, 58.3%), with some patients reporting more than 1 chief complaint (Table 1). A total of 261 patients had complete PFDI-20 scores available for analysis, with variable completion of the individual subscales: POPDI-6 (n=328), UDI-6 (n=504), and CRADI-8 (n=330).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Variables | Full Sample (n=833) | Sample stratified by average myofascial pain score (None=0, Mild=1–3, Moderate=4–6, Severe=7–10) | Sample with complete POPDI-6 (n=328) | Sample with complete UDI-6 (n=504) | Sample with complete CRADI-8 (n=330) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No/mild pain (n=205) | Moderate pain (n=208) | Severe pain (n=420) | p | |||||

| Age (years, mean, SD) | 55.1 (14.9) | 54.6 (15.4) | 53.9 (15.2) | 55.9 (14.6) | 0.215 | 55.7 (15.4) | 55.3 (15.4) | 56.1 (14.0) |

| Race (%) | 0.064 | |||||||

| White | 69.9 | 74.2 | 71.6 | 66.9 | 74.7 | 71.4 | 75.2 | |

| Black | 14.5 | 13.2 | 11.5 | 16.7 | 9.45 | 10.1 | 9.70 | |

| Other | 2.16 | 2.44 | 0.48 | 2.86 | 1.52 | 1.79 | 1.21 | |

| Unknown | 13.5 | 10.2 | 16.4 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 16.7 | 13.9 | |

| BMI (kg/m2, mean, SD) | 30.2 (7.5) | 29.9 (7.79) | 29.3 (7.17) | 30.8 (7.44) | 0.066 | 29.5 (7.0) | 29.6 (7.2) | 29.3 (7.02) |

| Parity (median, IQR) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.418 | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) |

| POP-Q Stage (%) | 0.003 | |||||||

| 0/1 | 72.8 | 78.8 | 62.4 | 74.9 | 66.3 | 69.5 | 68.9 | |

| 2 | 17.9 | 14.3 | 24.8 | 16.3 | 21.8 | 20.0 | 19.8 | |

| 3/4 | 9.4 | 6.9 | 12.9 | 8.9 | 12.0 | 10.6 | 11.3 | |

| Postmenopausal (%) | 67.7 | 62.7 | 62.0 | 73.0 | 0.004 | 67.4 | 67.7 | 67.9 |

| Ever tobacco use (%) | 46.4 | 48.7 | 42.3 | 47.4 | 0.986 | 43.6 | 43.0 | 44.5 |

| History of abuse (%) | 12.5 | 8.78 | 13.0 | 14.1 | 0.036 | 17.1 | 16.1 | 17.6 |

| Chief complaint(s) (%) | ||||||||

| Urinary symptoms | 91.8 | 91.2 | 92.8 | 91.7 | 0.933 | 90.6 | 91.7 | 90.0 |

| Bulge symptoms | 30.4 | 25.4 | 32.4 | 31.7 | 0.160 | 33.9 | 32.5 | 31.9 |

| Dyspareunia (%) | 51.8 | 44.8 | 50.5 | 55.8 | 0.014 | 52.6 | 53.4 | 51.7 |

| Pain | 58.3 | 52.2 | 49.5 | 65.7 | 0.0002 | 52.7 | 56.6 | 51.8 |

| Co-morbidities (%) | ||||||||

| Psychiatric diagnosis* | 30.9 | 31.7 | 28.9 | 31.4 | 0.952 | 32.0 | 29.2 | 31.2 |

| Chronic pain/fibromyalgia | 16.2 | 13.2 | 15.4 | 18.1 | 0.108 | 9.15 | 13.5 | 9.70 |

| Sciatica/low back pain | 7.92 | 7.32 | 4.81 | 9.76 | 0.082 | 6.40 | 7.34 | 5.45 |

| Chronic pelvic pain | 6.48 | 7.32 | 4.81 | 6.90 | 0.992 | 4.57 | 5.95 | 4.55 |

| Prior surgeries (%) | ||||||||

| Hysterectomy | 47.4 | 46.3 | 38.9 | 52.1 | 0.064 | 44.8 | 46.8 | 45.5 |

| Vaginal prolapse repair | 11.3 | 14.2 | 7.21 | 11.9 | 0.666 | 8.54 | 9.52 | 10.0 |

| Abdominal prolapse repair | 2.16 | 2.44 | 0.96 | 2.62 | 0.696 | 2.13 | 2.18 | 2.12 |

| Incontinence surgery | 20.5 | 22.4 | 13.9 | 22.9 | 0.543 | 18.9 | 19.3 | 18.5 |

Data presented for full sample stratified by myofascial pain score category identified on physical examination as well as for those samples with complete questionnaire responses for the respective questionnaires. P values presented for trend by pain category with the exception of p value for race (global p value). BMI=body mass index; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation; POP-Q=Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification; POPDI=Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory; UDI=Urogenital Distress Inventory; CRADI=Colorectal Anal Distress Inventory.

Psychiatric diagnoses include depression, anxiety, or bipolar disorder.

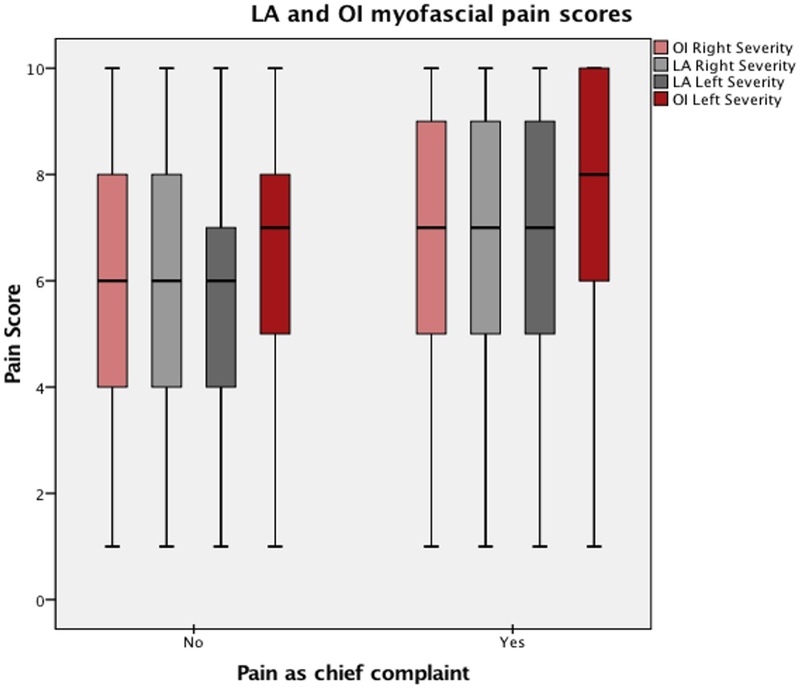

Prevalence of pelvic floor myofascial pain

Some degree of PFMP (pain score ≥1/10 in at least one muscle group) was identified on examination in 85.0% of patients. Most rated their pain as severe (50.4%), with fewer reporting moderate (25.0%) and mild (9.6%) pain. Even in women who did not present with pain, a high prevalence of moderate to severe PFMP was observed, although the severity of pain on examination was lower than in those who presented with pain (Figure 1). Higher pain scores were observed in the left OI than other sites. Patients with severe PFMP were significantly more likely to be postmenopausal, have a history of abuse, and endorse dyspareunia and pain (Table 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of pelvic floor myofascial pain scores among women who endorsed pain (‘Yes’) compared to those who denied pain (‘No’).

Median pain scores represented by solid line, boxes denote interquartile range. P<0.0001 for the comparison of scores for women who endorsed versus denied pain.

The presence of myofascial pain clustered by muscle group. Pain in the ROI was significantly correlated with a finding of pain in the LOI (r=0.702, p<0.0001) and pain in the RLA was significantly correlated with pain the LLA (r=0.725, p<0.0001). PFMP was also clustered by laterality: pain in the LOI was significantly correlated with pain in the LLA (r=0.670, p<0.0001) and pain in the ROI was significantly correlated with pain in the RLA (r=0.672, p<0.0001).

Correlation between pelvic floor myofascial pain severity and degree of pelvic organ prolapse symptom bother (POPDI-6)

Patients with complete responses were more likely to be white, have a lower BMI, and report a history of abuse. They were also less likely to present with pain, or to report chronic pain/fibromyalgia or vaginal prolapse repair (Supplement). There were no significant differences in the chief complaints of bulge or urinary symptoms between those who did and did not complete the POPDI-6. POP-Q Stage 2 or greater pelvic organ prolapse was identified in 27.3% (n=221) with mean leading edge of −1.5 (range −3–13). There was no difference in the percentage of patients reporting pelvic pressure (p=0.924), pelvic heaviness (p=0.359), or urinary frequency (p=0.794) based on POP-Q stage. The majority of patients with complete POPDI-6 responses had severe pain on palpation (n=167, 50.9%), while 98 (29.9%) had moderate and 63 (19.4%) had no or mild pain.

In unadjusted analyses, PFMP severity at each site was significantly correlated with several POPDI-6 items, including pressure in the lower abdomen, pelvic heaviness or dullness, and having to push on the vagina or around the rectum to have a bowel movement (Table 2). These correlations were typically strongest in the right OI. In contrast, PFMP severity was not correlated with seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge (except for the left LA), a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying (except for the right OI), or having to push up on a bulge to start or complete urination.

Table 2.

Correlation between severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory responses (POPDI) in women seeking care for pelvic floor disorder symptoms adjusted for postmenopausal status, 2014–16.

| Pelvic floor myofascial pain | POP-Q | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual sites | Total | |||||

| Do you usually experience… | ROI | RLA | LLA | LOI | ||

| …pressure in your lower abdomen? | 0.259*** | 0.107 | 0.136* | 0.125* | 0.157** | 0.001† |

| …heaviness or dullness in the pelvic area? | 0.202** | 0.117* | 0.195** | 0.135* | 0.156** | 0.072† |

| … a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel? | −0.003 | −0.003 | 0.113 | 0.056 | 0.033 | 0.570***† |

| Do you ever have to push on the vagina or around the rectum to have or complete a bowel movement? | 0.151** | 0.187** | 0.193** | 0.145* | 0.166** | 0.264***‡ |

| … a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying? | 0.121* | 0.067 | 0.055 | 0.051 | 0.054 | 0.021†† |

| Do you ever have to push up on a bulge in the vaginal area with your fingers to start or complete urination? | 0.068 | 0.058 | 0.104 | 0.033 | −0.033 | 0.128*†† |

| POPDI Total | 0.217** | 0.157** | 0.201** | 0.153** | 0.153* | 0.206**† |

| Subjective Summary Score | 0.293** | 0.128* | 0.154** | 0.138* | 0.140* | 0.041† |

| Objective Summary Score | 0.030 | 0.023 | 0.128* | 0.066 | 0.023 | 0.486***† |

| Prolapse leading edge | −0.116 | −0.097 | 0.023 | 0.030 | −0.089 | -- |

Pain scores are reported on scales of 0–10 for each site. Total score represents the summation of scores from each of the 4 sites (range 0–40). Objective prolapse severity is reported by leading edge. ROI, right obturator internus; RLA, right levator ani; LLA, left levator ani; LOI, left obturator internus;

, leading edge of prolapse;

, POP-Q point Bp;

, POP-Q point Ba.

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.0001≤p<0.01;

p<0.0001.

Spearman’s rank and partial rank correlation coefficients are presented. Subjective summary score includes responses to the following questions: do you usually experience pressure in your lower abdomen; do you usually experience heaviness or dullness in the pelvic area; do you usually experience a feeling of incomplete bladder emptying? Objective summary score includes response to the following questions: do you usually experience a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel; do you ever have to push up on a bulge in the vaginal area with your fingers to start or complete urination?

To further investigate the relationship between PFMP severity and “subjective” bulge symptoms (i.e. pressure and heaviness), compared to “objective” symptoms (i.e. seeing or feeling a bulge), we created “subjective” and “objective” summary scores. In these analyses, PFMP severity at each site examined and overall was significantly correlated with the “subjective” summary score, including questions pertaining to sensations of pressure, heaviness, and incomplete emptying; but not with the “objective” summary score, including questions related to a bulge that can be seen or felt, or the need to push on a bulge in the vaginal area to complete urination. One exception was a significant correlation between pain in the left LA and the objective score. Neither PFMP severity nor the subjective score were correlated with leading edge or POP-Q stage, whereas the objective score was correlated with both leading edge and POP-Q stage. This pattern of correlations remained largely unchanged after adjustment for postmenopausal status.

Correlation between pelvic floor myofascial pain severity and degree of urinary symptom bother (UDI-6)

Similar to patients with complete POPDI-6 scores, those with complete UDI-6 results were more likely to be white, have a lower BMI, and report an abuse history, and less likely to have chronic pain/fibromyalgia or a history of vaginal prolapse repair (Supplement). They were also more likely to be of unreported race, have lower parity, be nonsmokers, and report dyspareunia (Supplement). Bulge and urinary symptom chief complaint percentages were similar between patients who did and did not complete the UDI-6. Overall, severe pain was identified in 246 (48.8%) patients with complete UDI-6 responses, moderate pain in 157 (31.2%), and no or mild pain in 101 (20.0%).

In unadjusted analyses, PFMP scores at all sites and overall were significantly correlated with pain/discomfort in the lower abdomen/genital region (Table 3). PFMP at several individual sites was also significantly correlated with difficulty emptying the bladder (all sites), frequent urination (bilateral OI), and urine leakage associated with a feeling of urgency (bilateral OI). There was no correlation between PFMP and urine leakage related to coughing, sneezing, or laughing or small amounts of urine leakage.

Table 3.

Correlation between severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain and Urogenital Distress Inventory response (UDI) in women seeking care for pelvic floor disorder symptoms adjusted for post-menopausal status, 2014–16.

| Pelvic floor myofascial pain | Ba | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual sites | Total | |||||

| Do you usually experience… | ROI | RLA | LLA | LOI | ||

| … pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen or genital region? | 0.230*** | 0.205*** | 0.204*** | 0.167** | 0.192*** | 0.020 |

| … difficulty emptying your bladder? | 0.136** | 0.087 | 0.143** | 0.091 | 0.078 | 0.054 |

| … frequent urination? | 0.079 | 0.033 | 0.067 | 0.076 | 0.066 | −0.053 |

| … urine leakage associated with a feeling of urgency? | 0.081 | −0.004 | 0.064 | 0.059 | 0.016 | −0.136** |

| … urine leakage related to coughing, sneezing, or laughing? | 0.028 | −0.023 | 0.016 | −0.028 | 0.041 | 0.014 |

| … small amounts of urine leakage? | −0.005 | −0.076 | −0.032 | −0.004 | −0.015 | −0.059 |

| UDI-6 Total | 0.097* | 0.025 | 0.089 | 0.056 | 0.069 | −0.038 |

| “UDI-5” - No pain component | 0.043 | −0.029 | 0.044 | 0.015 | 0.020 | −0.039 |

Pain scores are reported on scales of 0–10 for each site. Total score represents the summation of scores from each of the 4 sites (range 0–40). Ba refers to POP-Q point Ba. “UDI-5” represents the total score after excluding results from the question addressing pain in the lower abdomen or genital region. ROI, right obturator internus; RLA, right levator ani; LLA, left levator ani; LOI, left obturator internus.

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.0001≤p<0.01;

p<0.0001.

Spearman’s partial rank correlation coefficients are presented.

PFMP in the right OI and left LA was significantly correlated with total UDI-6 score. This was largely driven by pain/discomfort in the lower abdomen/genital region. When this variable was removed (“UDI-5”), only pain in the right OI remained significantly correlated with UDIscore.

After controlling for postmenopausal status, overall PFMP severity remained significantly correlated with pain/discomfort in the lower abdomen/genital region (Table 3). Additionally, pain in the right OI remained significantly correlated with difficulty emptying and overall UDI-6; and pain in the left LA remained significantly correlated with difficulty emptying.

Correlation between pelvic floor myofascial pain severity and degree of bowel symptom bother (CRADI-8)

Similar to patients with complete POPDI-6 and UDI-6 responses, those with complete CRADI-8 responses were more likely to be white and have a history of abuse but less likely to endorse chronic pain/fibromyalgia. They were also less likely to endorse pain or sciatica/low back pain (Supplement). Patients with complete CRADI-8 responses were similar to those with incomplete responses in the chief complaints of bulge and urinary symptoms. Overall, severe pain was noted in 165 (50%), moderate pain in 100 (33.3%), and no or mild pain in 65 (19.7%).

In unadjusted analyses, overall PFMP severity was significantly correlated with the sensation of incomplete rectal emptying, anal incontinence to flatus, pain with defecation, and total CRADI-8 score (Table 4). Considering pain at individual sites, pain in the right OI was significantly correlated with needing to strain and the overall CRADI-8 score. Bilateral OI PFMP was significantly correlated with anal incontinence to loose stool and flatus, and pain in the right OI and left LA was significantly correlated with sensation of incomplete emptying and pain with defecation.

Table 4.

Correlation between severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain and Colorectal/Anal Distress Inventory response (CRADI) in women presenting with pelvic floor disorder symptoms adjusted for post-menopausal status, 2014–16.

| Pelvic floor myofascial pain | Bp | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual sites | Total | |||||

| Do you… | ROI | RLA | LLA | LOI | ||

| …feel you need to strain too hard to have a bowel movement? | 0.105 | −0.005 | 0.028 | −0.012 | 0.025 | 0.162** |

| … feel you have not completely emptied your bowels at the end of a bowel movement? | 0.119* | 0.047 | 0.106 | 0.067 | 0.125* | 0.137* |

| … usually lose stool beyond your control if your stool is well formed? | 0.039 | 0.017 | −0.021 | 0.059 | 0.004 | 0.037 |

| …usually lose stool beyond your control if your stool is loose? | 0.087 | 0.028 | −0.015 | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.060 |

| …usually lose gas from the rectum beyond your control? | 0.101 | 0.034 | 0.016 | 0.066 | 0.115* | 0.106 |

| …usually have pain when you pass your stool? | 0.168** | 0.104 | 0.161** | 0.101 | 0.121* | 0.068 |

| …experience a strong sense of urgency and have to rush to the bathroom to have a bowel movement? | 0.072 | 0.054 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.058 | 0.047 |

| Does part of your bowel ever pass through the rectum and bulge outside during or after a bowel movement? | 0.032 | 0.028 | 0.023 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.135* |

| CRADI Total | 0.104 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.045 | 0.090 | 0.138* |

Pain scores are reported on scales of 0–10 for each site. Total score represents the summation of scores from each of the 4 sites (range 0–40). Bp refers to POP-Q point Bp. ROI, right obturator internus; RLA, right levator ani; LLA, left levator ani; LOI, left obturator internus.

0.01≤p<0.05;

0.0001≤p<0.01;

p<0.0001.

Spearman’s partial rank correlation coefficients are presented.

After controlling for menopausal status, overall PFMP scores remained correlated with sensation of incomplete rectal emptying, anal incontinence to flatus, and pain with defecation (Table 4). Pain in the right OI remained significantly correlated with sensation of incomplete rectal emptying and pain with defecation. Left LA pain also remained significantly correlated with pain with defecation.

Comment

Principal Findings

PFMP was common in patients seeking evaluation for pelvic floor symptoms. Interestingly, patients who did not endorse pain were still found to have moderate to severe pain with palpation of the bilateral OI and LA muscles. The severity of pain elicited on our standardized pelvic floor muscle examination was significantly correlated with the degree of bother of common pelvic floor symptoms related to prolapse and defecatory dysfunction, raising the possibility that PFMP may contribute to symptom severity.

Results

In 2013, Adams et al observed an association between the presence of levator ani myalgia and higher mean scores on the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory.2 We present consistent findings and explore this relationship further. We found that not only the presence of PFMP, but also its location and severity affected the degree of symptom bother. Although some of our unadjusted correlations were explained by postmenopausal status, a state associated with both vulvovaginal atrophy and pelvic floor disorder symptoms, other correlations persisted, especially for pain in the right OI, suggesting an independent influence of PFMP on these symptoms (i.e., subjective symptoms of prolapse, lower abdominal/genital pain, sensation of incomplete rectal emptying, and pain with defecation). If these correlations are ultimately found to be causal, understanding the specific distribution of myofascial pain throughout the pelvic floor will be important to guide appropriate physical therapy.

The prevalence of PFMP in our cohort was 85%. While this may seem high, this represents all patients who reported any degree of pain on examination of any of the pelvic floor muscle groups. For example, if a patient reported pain 1/10 in severity (thus very mild) in only one muscle group, she would be captured in this 85%. The prevalence we found in our population is consistent with prevalence estimates by other authors who perform universal assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain.14,15

Clinical and Research Implications

PFMP in the right OI was significantly correlated with increasing bother on each subscale and many individual symptoms, even after controlling for postmenopausal status. We also found an increased median pain score in the left OI compared to the right. Although the mechanisms linking these opposite-sided findings are not entirely clear, we hypothesize they may result from handedness-driven biomechanics. For example, right-handed women often hold heavy objects (i.e., young children, large purses, etc.) on their left side in order to have their right hand available for other tasks. These practices result in unequal weight distribution that, over time, may contribute to asymmetric muscle strain, particularly in the hip and pelvic floor muscles. Studies in school-age children have demonstrated that asymmetrical backpack carriage negatively impacts posture and gait.16 As a result, PFMP may arise due to chronic, asymmetrical muscle strain, posture, and altered gait. This relationship is intriguing and worthy of further investigation as lifting and carrying recommendations for postpartum women, who may already have musculoskeletal injuries from pregnancy and delivery, could be impacted. Asymmetrical examination scores may also be related to handedness of the examiner if differential force were applied to muscle groups based on the examiner’s dominant hand. We suspect this to be unlikely as we have previously shown consistency in examination pressure between examiners when measured quantitatively and examiners often use the right hand for examination of the right side and the left hand for the left side of the examination for ergonomic reasons.10

PFMP was significantly correlated with several prolapse symptoms on the POPDI-6 but not with objective prolapse severity based on leading edge or POP-Q stage. In particular, PFMP at all sites and overall was significantly correlated with bothersome pressure in the lower abdomen or heaviness/dullness in the pelvis, but not with “objective” symptoms, such as seeing or feeling a vaginal bulge, or having to push up on a bulge to start or complete urination. Although PFMP severity was also significantly correlated with the need to push on the vagina or around the rectum to have or complete a bowel movement, we did not interpret this symptom as either an “objective” or “subjective” symptom of prolapse because it may capture other nonprolapse mechanisms such as pelvic floor muscle dysfunction with defecation. This symptom aside, our objective and subjective prolapse findings suggest an alternative explanation for pressure or heaviness symptoms besides objective prolapse. For instance, PFMP may possibly be misinterpreted as a feeling of pressure or heaviness because of the anatomic proximity of the pelvic floor muscles and vagina. In this case, PFMP might be important to consider in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with prolapse symptoms who are not found to have significant prolapse on examination, as they may be more likely to benefit from myofascial pain-directed therapies like pelvic floor physical therapy than more invasive prolapse therapies.

Strengths and Limitations

The examinations were performed by two fellowship-trained, right-handed urogynecologists in a systematic, standardized way. This protocol was subsequently studied and shown to be reliable and reproducible among four providers.10 While it is possible that some variability in this examination existed prior to our formalization and publication of the protocol, this would likely have led to non-differential misclassification of the measure and an attenuation of correlations. Nevertheless, we still observed several significant correlations.

Based on our clinical impression, we expected to observe a significant correlation between PFMP and “irritative” voiding symptoms. Unfortunately, the only “irritative” symptoms we were able to explore in our analysis were frequent urination and urgency incontinence, which were not correlated with PFMP after controlling for postmenopausal status. Therefore, use of the full 19-item UDI, which includes a total of six irritative symptoms (urinary urgency, leakage associated with urgency, frequency, night-time urination, leakage of a large amount of urine, and bedwetting),17 may be necessary to address our original hypothesis. The same may also be true for other symptoms assessed on the full PFDI but not the shorter PFDI-20.

In addition to use of a shorter instrument, our analyses were limited by the fact that many patients did not complete the PFDI-20, or all of its subscales. If women with symptoms were more likely to complete the section related to their symptoms, this might have constrained the outcome distribution to greater symptoms and possibly made it more difficult to detect a correlation between PFMP and symptoms. However, when we compared patients with and without complete PFDI-20 responses, we observed similar prevalence of the chief complaints of prolapse, urinary, and bowel symptoms, suggesting a lack of appreciable selection bias within our sample. Therefore, missing responses are likely to have only reduced our sample size and limited our power to detect significant correlations.

We recognize that, while many of the correlations between PFMP severity and pelvic floor symptoms were highly significant, the correlation coefficients were weak. These weaker correlations were expected because we were estimating the correlation between two different constructs (i.e., PFMP and pelvic floor symptoms) rather than between different measures of the same construct. For instance, the correlation between patient-reported prolapse (i.e., experiencing a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel) and physician-measured degree of prolapse (i.e., POP-Q examination), two measures of the same construct, was only 0.570. In addition, the correlation between physician-measured degree of prolapse and a known consequence of prolapse (i.e., pushing up on a bulge in the vaginal area with your fingers to start or complete urination) was even weaker (r=0.130). Therefore, we did not expect the correlation between PFMP, a possible contributor to pelvic floor disorder symptoms, and the severity of pelvic floor disorder symptoms, to be stronger than these correlations.

Conclusions

In summary, we report significant correlations between PFMP severity and degree of pelvic floor symptom bother in patients evaluated at a tertiary urogynecologic practice. These correlations support the hypothesis that PFMP underlies some pelvic floor symptoms, which are often attributed to pelvic organ prolapse or bladder or bowel pathology. Further investigation to clarify this relationship is needed. In the future, we may find that addressing underlying PFMP results in significant improvement in these symptoms. If true, this would represent an important, non-pharmacologic, non-operative therapeutic strategy to improve symptoms for thousands of women while sparing them the risks and side effects associated with medications or surgery. Given the high prevalence of PFMP in patients presenting for evaluation of pelvic floor symptoms and correlation between PFMP severity and degree of bother for many of these symptoms, all patients presenting for evaluation of pelvic floor symptoms should undergo a routine assessment for PFMP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Meister is supported by an NIH Reproductive Epidemiology Training Grant (T32HD055172–08) and a Clinical and Translational Science Award held at Washington University in St. Louis (UL1 TR002345)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

- This study was conducted to investigate the relationship between pelvic floor myofascial pain and pelvic floor symptoms.

- We found that pelvic floor myofascial pain is common in patients with pelvic floor symptoms, especially pelvic pressure, heaviness, difficulty with bladder emptying, lower abdominal/genital pain, anal incontinence, and sensation of incomplete rectal emptying, and that the severity of pelvic floor myofascial pain correlates with the degree of symptom bother.

- These findings suggest that pelvic floor myofascial pain may drive pelvic floor symptoms in some patients, especially those with pelvic pressure and heaviness who are not found to have objective prolapse on examination. Therapies directed at addressing myofascial pain may potentially lead to significant symptomatic improvement in these patients.

Contributor Information

Melanie R. MEISTER, St. Louis, Missouri, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

Siobhan SUTCLIFFE, St. Louis, Missouri; Department of Surgery, Division of Public Health Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis.

Asante BADU, Bronx, New York; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Chiara GHETTI, St. Louis, Missouri; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

Jerry L. LOWDER, St. Louis, Missouri; Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Female Pelvic Medicine & Reconstructive Surgery, Washington University in St. Louis.

References

- 1.Spitznagle TM, Robinson CM. Myofascial pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am 2014; 41: 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams K, Gregory WT, Osmundsen B, Clark A. Levator myalgia: why bother? Int Urogynecol J 2013; 24: 1687–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moldwin RM, Fariello JY. Myofascial trigger points of the pelvic floor: associations with urological pain syndromes and treatment strategies including injection therapy. Curr Urol Rep 2013; 14: 409–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kavvadias T, Baessler K, Schuessler B. Pelvic pain in urogynaecology. Part 1: evaluation, definitions, and diagnoses. Int Urogynecol J 2011; 22: 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richenberg JL. Ultrasound of the bladder In: Allan PL, Baxter GM, Weston MJ. Clinical Ultrasound (Third Edition). Churchill Livingstone; 2011: I1–I41. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenner A Brain reaction to bladder filling predicts response to pelvic floor muscle training. Nat Rev Urology. 2015; 12: 242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, Walters MD. Functional bowel and anorectal disorders in patients with pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 193(6): 2105–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharucha AE, Wald A, Enck P, Rao S. Functional anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006; 130(5): 1510–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meister MR, Shivakumar N, Sutcliffe S, Spitznagle T, Lowder JL. Physical examination techniques for the assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 219(5): 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meister MR, Sutcliffe S, Ghetti C, Chu CM, Spitznagle T, Warren DK, Lowder JL. Development of a standardized, reproducible screening examination for assessment of pelvic floor myofascial pain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 220(3): 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42(2): 377–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barber MD, Kuchibhatla MN, Pieper CF, Bump RC. Psychometric evaluation of 2 comprehensive condition-specific quality of life instruments for women with pelvic floor disorders. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 185: 1388–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barber MD, Walter MD, Bump RC. Short forms of two condition-specific quality-of-life questionnaires for women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDI-20 and PFIQ-7). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005; 193: 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Kalinowski SE, et al. Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis. Urology 2007; 70(1): 16–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassaly R, Tidwell N, Bertolino S, et al. Myofascial pain and pelvic floor dysfunction in patients with interstitial cystitis. Int Urogynecol J 2011; 22(4): 413–8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong Y, Cheung CK. Gait and posture responses to backpack load during level walking in children. Gait & Posture. 2003; 17(1): 28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shumaker SA, Wyman JF, Uebersax JS, McClish D, Fantl JA for the Continence Program in Women (CPW) Research Group. Health-related quality of life measures for women with urinary incontinence: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Quality of Life Research. 1994; 3: 291–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.