Abstract

Background:

Little population-level evidence exists to guide the development of interventions for people with dementia in non-nursing home settings. We hypothesized people living at home with moderately severe dementia would differ in social, functional, and medical characteristics from those in either residential care or nursing home settings.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study using pooled data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS), an annual survey of a nationally-representative sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

Setting:

USA, national sample.

Participants:

Respondents newly meeting criteria for incident moderately severe dementia, defined as probable dementia with functional impairment: 728 older adults met our definition between 2012-2016.

Measurements:

Social characteristics examined included age, gender, race/ethnicity, country of origin, income, educational attainment, partnership status, household size. Functional characteristics included help with daily activities, falls, mobility device use, limitation to home or bed. Medical characteristics included comorbid conditions, self-rated health, hospital stay, symptoms, and dementia behaviors.

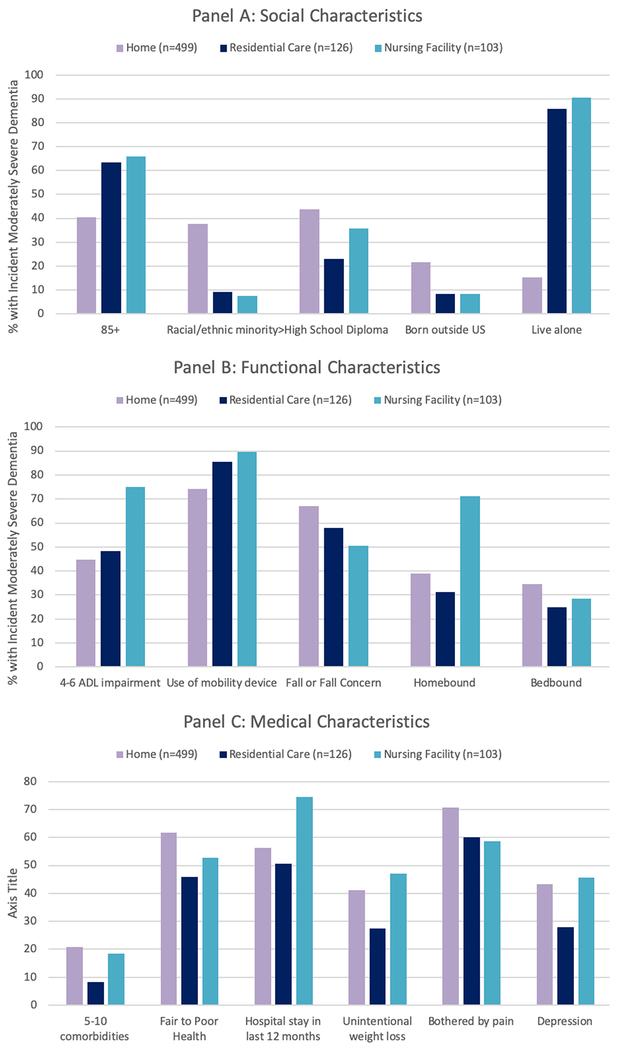

Results:

Extrapolated to the population, an estimated 3.3 million older adults developed incident moderately severe dementia between 2012-2016. Within this cohort, 64% received care at home, 19% in residential care, and 17% in a nursing facility. Social, medical and functional characteristics differed across care settings. Older adults living at home were 2-5 times more likely be members of disadvantaged populations and had more medical needs: 71% reported bothersome pain compared to 60% in residential care or 59% in nursing homes.

Conclusion:

Over a 5-year period, 2.2 million people lived at home with incident moderately severe dementia. People living at home had higher prevalence of demographic characteristics associated with systematic patterns of disadvantage, more social support, less functional impairment, worse health and more symptoms compared to people living in residential care or nursing facilities. This novel study provides insight into setting-specific differences among people with dementia.

Keywords: dementia, care setting, disparities, home

INTRODUCTION

Dementia syndromes are progressive and incurable illnesses1 causing significant public health burden on families, the long-term care system, and the economy. In the United States, more than 5.7 million older adults over 65 live with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias2. Minimal evidence exists to inform care interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia. The limited existing research focuses on persons with advanced dementia residing in nursing facilities3–5 and many people assume all care for people with advanced dementia happens in institutional settings. Yet nursing facility residency is decreasing nationwide even as the population of older adults rapidly increases6. Eighty percent of homebound older adults have dementia7 and up to 59% of older adults with dementia die at home8. Some of these people likely receive home-based primary, geriatric, or palliative care; many more likely do not.9 Hospice organizations provide end-of-life care at home but services are often not tailored to the specific needs of people with dementia. Understanding how people with dementia who live at home compare to those in nursing facilities and other settings may facilitate improvements in clinical care, interventions, and policy.

The objective of this study was to examine setting-specific differences in characteristics of older adults with dementia, comparing home, residential care, and nursing facilities at a similar stage of disease. As care needs sharply escalate with disability in activities of daily living (ADL), older adults with dementia who have recently progressed to having significant impairments in cognitive and physical function, such as those with incident moderately severe dementia, are an ideal target for interventions that provide the person and care partners with preparation and support for more intensive geriatric palliative care needs.10 This study uses a newer nationally-representative dataset with annual waves of data to conduct the first population-level examination of differences in social, functional, or medical characteristics of older adults with incident moderately severe dementia.

METHODS

Design:

We compared older adults with incident moderately severe dementia by care settings, pooling data across 5 waves of the National Health Aging and Trends Study (NHATS). Since 2011, NHATS follows a nationally-representative cohort of Medicare enrollees aged 65 years and older with in-person annual interviews. Response rates range from 71% in 2011 to 91% in subsequent interviews.11 The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board considered this study to be exempt research.

Participants:

We used the NHATS algorithm designating probable dementia if respondents (or a proxy) report a physician diagnosis of dementia, score 3 on the proxy-reported AD-812, or are impaired (< 1.5 standard deviations below mean) on 2 of 3 domains on the self-reported cognitive interview (memory, orientation, executive functioning)13. These criteria have moderate sensitivity (69%), excellent specificity (89%), and are validated for use in community-based epidemiologic surveys13.

We defined “moderately severe dementia” as those individuals meeting the NHATS criteria for probable dementia who also reported difficulty with one of three ADLs (dressing, bathing, or toileting – correlating to the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST)14 stage 6a-c) and difficulty with one of two cognitively-oriented instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs: managing medications or finances).

Of 12,427 total NHATS participants, we excluded individuals missing first-round demographic and cognitive data (n=869). We focused on NHATS participants with incident moderately severe dementia, meaning they did not meet criteria in the prior NHATS round. Of the remaining 11,558 participants, 728 older adults met our definition of incident moderately severe dementia in any wave between 2012-2016.

Measurements:

We created mutually exclusive categories for care settings using NHATS questions about the participant’s living setting and building structure: home, residential care, or nursing facility. For social characteristics, we examined respondent type (self vs. proxy), age, gender, race/ethnicity, born in the United States, annual income, educational attainment, metropolitan location, marital status, living arrangement, household size, and social network size. For functional characteristics, we used respondents’ difficulty with IADLs or ADLs, falls or fall concerns in last month, use of mobility devices, ability and frequency of leaving the home7 or bed. For medical characteristics, we included respondents’ medical conditions, self- or proxy-rated health, reported hospital stays in last year, weight loss, symptoms (pain, breathing, depression, anxiety) and proxy-reported dementia behaviors.

Analyses:

We report descriptive statistics stratified by residential care settings (home, residential care [RC], and nursing facilities [NF]). Chi-square tests for categorical variables or t-tests/Wilcoxon tests for continuous measures were conducted to determine statistically significant differences between setting-stratified subpopulations. All analyses were weighted to adjust for unequal probability of subject selection and to account for the complex survey design variables11. For population-level estimates, we used population weights and compared those with incident moderately severe dementia to the number of community-dwelling people at risk. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata, version 14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Between 2012-2016, 728 older adults developed incident moderately severe dementia. Of these, 64% lived at home (n=499), 19% lived in residential care (n=126), and 17% lived in a nursing facility (n=103). Proxy-reported data differed by residential site (home 50.3%, residential care 43.6%, nursing facilities 66.4%, p=0.004).

Using survey weights, we estimate the national 5-year incidence of moderately severe dementia to be: 2,127,532 at home, 632,981 in residential care, and 576,611 in a nursing facility (total = 3,337,124). We estimate an overall 5-year incidence rate of 5.8% among Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older.

Social characteristics varied by setting of care among older adults with incident moderately severe dementia (Table 1). As expected, those living at home were younger (mean age 82.1 at home vs. 85.8 in RC or 86.9 in NF, p<0.001) and more likely to be partnered (45.1% home, 16.4% RC, 21.8% NF, p<0.001). A small but notable portion of people with dementia lived alone at home, meaning not with a partner or others (15.3% home vs. 85.9% RC vs. 90.6% NF, p<0.0001). People living at home were more likely to be: black (11.8% home vs. 3.4% RC vs. 6.4% NF, p<0.001), not born in United States (21.7% home vs. 8.2% RC vs. 8.4% NF, p=0.0003), and to have less educational attainment (43.7% with less than high school diploma at home vs. 23.0% RC vs. 35.8% NF, p=0.0095). Income levels below $25,000, the amount used in many states as the eligibility cutoff for Medicaid-paid nursing facilities, were highest among nursing home residents (73.5%). However, the group with the highest prevalence of extreme poverty (<$11,000 annually) were those living at home (26.1% at home vs. 19.1% RC vs. 17.5% NH). The social characteristics of older adults with dementia in residential care more closely resembled those in nursing facilities.

Table 1:

Social Characteristics of People with Incident Moderately Severe Dementia, Comparing Home, Residential Care and Nursing Facility Care Settings in the National Health Aging and Trends Study 2011-2016

| Home (n=499) % | Residential Care (RC) (n=126) % | Nursing Facility (NF) (n=103) % | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean [SD]) | 82.1 (±8.2) | 85.8 (±6.9) | 86.9 (±5.9) | <.001 |

| Age 85+ (vs. 65-84) | 40.5 | 63.3 | 65.8 | <.001 |

| Female | 59.8 | 64.0 | 65.8 | 0.60 |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001 | |||

| Black/African American | 11.8 | 3.4 | 6.4 | |

| Latinx/or Other1 | 25.9 | 5.81 | 1.11 | |

| White | 62.3 | 90.8 | 92.5 | |

| Not born in US | 21.7 | 8.2 | 8.4 | <.001 |

| Income2 | ||||

| <$11,000 | 26.1 | 19.1 | 17.5 | 0.019 |

| 11,000-$24,999 | 36.7 | 37.7 | 56.0 | |

| 25,000+ | 37.2 | 43.2 | 26.5 | |

| Education < high school diploma | 43.7 | 23.0 | 35.8 | 0.009 |

| Metropolitan (vs not)4 | 82.3 | 84.2 | 74.3 | 0.228 |

| Support Characteristics | ||||

| Partnership status3 | <.001 | |||

| Partnered | 45.1 | 16.4 | 21.8 | |

| Unpartnered | 11.5 | 14.5 | 29.0 | |

| Widowed | 43.4 | 69.2 | 49.1 | |

| Live alone5 | 15.3 | 85.9 | 90.1 | <.001 |

| 1+ person in social network6 | 47.6 | 52.2 | 28.2 | 0.009 |

Latinx describes all people of Spanish-speaking Latin American Heritage; less than 11 individuals in 2 cells.

Includes social security, pension, earned income, retirement account withdrawals, interest/dividends etc. at baseline; missing values were replaced using the first of five income imputations provided by NHATS. Trichotomized at $11,000 for 100% FPL in 201227 and $25,000 for 300% the Social Security Income limit in 2012 ($698/month28), the amount used in many states to determine eligibility criteria for Medicaid-paid nursing home.29

Compares partnered respondents (married or living together), widowed respondents, and unpartnered respondents (divorced, separated, never married, other).

Living arrangement compares respondents/proxies reporting living alone compared to with spouse/partner, or with spouse/partner and others.

Compares people reporting 1 or more people in their social network to those who report no one to talk to or whose proxies are responding on their behalf.

Metropolitan location indicates whether the sample person lived in a metropolitan area or not based on Rural-Urban Continuum Codes.11

Functional and medical characteristics of participants are described in Table 2. Older adults with incident moderately severe dementia living at home and in residential care had lower counts of ADL difficulty (3.3 ADL impairment at home, 3.2 RC, 4.5 NF, p<0.0001). People at home were more likely to use a cane (40.5% home, 16.0% RC, 9.8% NF, p<0.0001) and people in residential care more likely to use a walker (50.3% home, 66.6% RC, 48.1% NF, p=0.0128). Notably, people at home had the highest prevalence of falls or fall concerns in the last month (67.1% home, 57.9% RC, 50.4% NF, p=0.0122) as well as the highest level of 4-6 IADL difficulty (90.7% home, 84.7% RC, 80.0% NF, p=0.0125).

Table 2:

Functional and Medical Characteristics of People with Incident Moderately Severe Dementia, Comparing Home, Residential Care and Nursing Facility Care Settings in the National Health Aging and Trends Study 2011-2016

| Home (n=499) | Residential Care (RC) (n=126) | Nursing Facility (NF) (n=103) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count of IADL disability1 (mean [SD]) | 4.0 (±0.7) | 4.1 (±0.7) | 4.0 (±0.6) | 0.999 |

| Count of ADL disability2 | 3.3 (±1.7) | 3.2 (±1.8) | 4.5 (±1.3) | <.001 |

| Fall in last month or fall concerns3 | 67.1 | 57.9 | 50.4 | 0.012 |

| Mobility device used | ||||

| Cane | 40.5 | 16.0 | 9.8 | <.001 |

| Walker | 50.3 | 66.6 | 48.1 | 0.013 |

| Wheelchair | 28.5 | 43.8 | 78.5 | <.001 |

| Degree of home limitation4 | <.001 | |||

| Not homebound | 19.5 | 26.5 | 2.4 | |

| Semi-homebound | 41.5 | 42.2 | 26.5 | |

| Completely homebound | 38.9 | 31.3 | 71.1 | |

| Degree of bed limitation4 | <.001 | |||

| Not Bedbound | 36.4 | 40.3 | 16.7 | |

| Semi-bedbound | 29.1 | 34.8 | 55.0 | |

| Completely bedbound | 34.5 | 24.9 | 28.4 | |

| Number of chronic conditions5 (mean [sd]) | 3.2 (±1.6) | 2.6 (±1.4) | 3.1 (±1.5) | 0.031 |

| Fair or Poor Health (vs. Good to Excellent) | 61.7 | 45.9 | 52.7 | 0.043 |

| Hospital stay in last 12 months | 56.4 | 50.5 | 74.6 | 0.004 |

| Weight loss | 0.028 | |||

| None | 54.2 | 70.5 | 47.7 | |

| Intentional | 4.8 | 2.1 | 5.1 | |

| Unintentional | 41.1 | 27.4 | 47.1 | |

| Bothered by Pain | 70.8 | 60.1 | 58.6 | 0.040 |

| Pain limits activities | 52.7 | 38.1 | 39.5 | 0.019 |

| Breathing problems | 33.2 | 27.3 | 30.0 | 0.482 |

| Anxiety (GAD2 score 3-6)6 | 34.6 | 26.2 | 31.7 | 0.434 |

| Depression (PHQ2, 3-6)6 | 43.3 | 27.8 | 45.7 | 0.024 |

| Behavioral Symptoms7 | ||||

| Got lost in familiar environment | 17.8 | 23.5 | 24.5 | 0.011 |

| Wandered off | 4.8 | 7.9 | 6.28 | 0.018 |

| Cannot be left alone for an hour | 35.1 | 31.9 | 49.5 | 0.026 |

Help with laundry, shopping, preparing food, managing money, or taking medications. At least one of the latter two variables were required for inclusion in the cohort.

Help with eating, transferring, walking inside, dressing, bathing, and toileting – at least one of the latter three variables were required for inclusion in the cohort.

We combined NHATS questions about falls (fall, slip, or trip) in last month or worry about falling in last month into a single variable.

Limitations to home or bed uses information in NHATS on ability and frequency of leaving that setting, based on the definition developed by Ornstein et al.7

Includes doctor-identified heart attack, heart disease, high blood pressure, arthritis, osteoporosis, diabetes, lung disease, stroke, cancer, hip fracture/break.

Assessments of depression (PHQ-2) and anxiety (GAD-2) experienced in the last 2 weeks. PHQ2 is the 2-item Patient Health Questionnaire (score range, 0-6); GAD-2 is the Generalized Anxiety Disorder screening tool (score range, 0-6), dichotomized at 330).

Only proxies were asked whether behaviors associated with dementia were present.

Less than 11 people in the cell.

Older adults living at home with incident moderately severe dementia had an overall worse picture of health (Table 2). They exhibited more comorbidities (32.3% having 5-10 comorbidities at home, 15.3% RC, 29.5% NF, p=0.0017), worse health (61.7% health fair or poor, 45.9% RC, 52.7% NF, p=0.0429), and more bothersome pain (70.8% home, 60.1% RC, 58.6% NF, p=0.0398). Even when no differences were seen by care setting, symptom burden was notable: 26-70% of the study population experienced pain, dyspnea, anxiety or depression in any care setting.

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative sample of older adults with incident moderately severe dementia, we found that living at home is associated with systematic patterns of disadvantage and disparities in care: being a racial/ethnic minority, not being born in the United States, and having less than a high school education (Figure 1). Older adults living at home also had worse health and more symptoms. Fifteen percent of older adults with dementia lived at home alone rather than with partners.

Figure 1: Summary of Key Significant Differences in Social, Functional and Medical Characteristics Among Older Adults with Incident Moderately Severe Dementia, Stratified by Care Setting.

Note: All differences comparing home vs. residential care vs. nursing home significant at p>0.05.

Our findings in this nationally-representative dataset are consistent with the limited prior research: a single-state study using data from 2001 found that older adults with advanced dementia at home in the last year of life (compared to those in nursing homes) were more likely to be non-white, more likely to have pain and dyspnea, and less likely to have advance directives despite frequent hospitalizations15. Another study among community-dwelling people with dementia found that higher unmet needs (typically home or personal safety, general health care, and daily activities) are associated with non-white race, lower education, higher cognitive function, more neuropsychiatric symptoms, lower quality of life, and having caregivers who spend fewer hours a week with the person with dementia.16 For most older adults, including older adults with dementia17 and their caregivers,18 home is the preferred setting of care. Policymakers have historically supported the movement away from institutions: in 2013, Medicaid spending on home and community-based services surpassed spending on institutional care19. Older adults living at home with advancing dementia may have lessons to teach us on how to “successfully” live in the community with high social, medical, and functional needs. However, future research should explore to what extent living at home with dementia is achieved at the expense of tradeoffs on family members’ mental, physical, and financial wellbeing, or result in disparities in unmet needs or access to high quality dementia care.

The alternative is expensive. In 2018, the median monthly cost of assisted living (one type of residential care) in the United States was $4000 ($48,000 annually) while a semi-private room in a nursing facility cost $7,441 ($89,292).20 Medicare does not pay for most long term supports and services; beneficiaries with high needs (such as people with dementia) risk incurring substantial costs.21 Medicaid pays for a portion of these costs for low-income beneficiaries, but coverage of non-nursing home residential care varies substantially by state2. Thus, it is not surprising that our study found a higher percentage of people with dementia in residential care, as compared to at home or nursing facilities, were in the highest income category.

Our study aligns with prior research among people with dementia showing associations between being older, white, single, living alone, and/or having 3+ ADL dependencies and nursing home placement22,23. Black and Latinx older adults with any diagnosis tend to stay longer in the community before nursing facility placement, at which time they are more physically and cognitively impaired24. Our study supports a similar hypothesis among people with dementia, as we observed a higher prevalence of non-white people living at home with incident moderately-severe dementia. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the impact of social determinants of health (like race, socioeconomic status, geography, housing, transportation, community supportive services) on differences in patterns of care needs and settings over time among people with moderately severe and advancing dementia. Such longitudinal studies can work in concert with systematic efforts to improve systems of care and clinical practice to better serve the needs of people with dementia and caregivers, such as through quality improvement initiatives or implementation, adaptation, and dissemination of evidence-based interventions.

Limitations:

Our definition of incident moderately severe dementia reflects the overlay of disability on dementia that is consistent with prior definitions of serious illness25; this is a population measure and does not reflect the detailed neuropsychological testing used to establish dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease research centers. For 48.2% of the sample, data were self-reported. NHATS does not facilitate examination of geographically-varying factors that impact community-based care, such as area poverty, home-based medical and long-term supports and services, caregiver training and support, workforce adequacy, and care coordination; neighborhood- and community-based factors beyond urban/rural distinctions should be examined in future studies.

Conclusion:

This study addresses important evidence gaps regarding setting-specific differences among people with advancing dementia. To our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the incidence of moderately severe dementia at one in twenty community-dwelling older adults over a 5-year time period, the majority of whom live at home. Efforts to transform clinical practice, systems, and policy require clear data-driven understandings of experiences and needs of different subpopulations of older adults with dementia and their families. This information is essential for building evidence-based care that achieves the goals of the National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: enhancing care quality and expanding supports for caregivers and older adults with dementia living in any setting of care.26

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sponsor’s Role: No sponsor was involved in the design, methods, recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Funding Sources and Previous Presentations:

Research reported in this publication was conducted with support from: the UCSF Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center funded by National Institute on Aging (P30 AG044281 – KH, KC); Career Development Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (KL2TR001870 - KH); UCSF Hellman Fellows Award (KH); National Palliative Care Research Center Junior Faculty Award (KH); Atlantic Fellowship of the Global Brain Health Institute (KH); Harris Fishbon Distinguished Professor in Clinical Translational Research and Aging (CR); Tideswell Innovation and Implementation Center for Aging & Palliative Care Research (CR); National Institute on Aging (K24 AG031155 - KY); VA Quality Scholars Program funded through the VA Office of Academic Affiliations Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration (Grant AF-3Q-09-2019-C - LH).

Footnotes

Twitter Handles of Co-Authors:

Christine Ritchie: @RitchieCS

Lauren Hunt: @laurenhuntRN

Ken Covinsky: @geri_doc

Alex Smith: @AlexSmithMD

Preliminary findings were presented at the annual meetings of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, and AcademyHealth. This paper was improved by feedback from Emily R. Adrion, Nicole Boyd, W. John Boscardin, and colleagues associated with the UCSF Pepper Center.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lee M, Chodosh J. Dementia and life expectancy: what do we know? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(7):466–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer’s Association. 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;14(3):367–429. https://www.alz.org/media/HomeOffice/Facts%20and%20Figures/facts-and-figures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy E, Froggatt K, Connolly S, et al. Palliative care interventions in advanced dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD011513. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011513.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Cohen S, Hanson LC, Habtemariam D, Volandes AE. An Advance Care Planning Video Decision Support Tool for Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. June 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Jones RN, Prigerson H, Volicer L, Teno JM. Advanced dementia research in the nursing home: the CASCADE study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(3):166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, et al. Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013 – 2014. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_038.pdf. Accessed June 14, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the Homebound Population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1180–1186. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callahan CM, Tu W, Unroe KT, LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Clark DO. Transitions in Care in a Nationally Representative Sample of Older Americans with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(8):1495–1502. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao N (Aaron), Ritchie C, Cornwell T, Leff B. Use of Home-Based Medical Care and Disparities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2018;66(9):1716–1720. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative Care for the Seriously Ill. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(8):747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasper JD, Freedman VA. National Health and Aging Trends Study User Guide: Rounds 1-6 Final Release. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2017. www.NHATS.org. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology. 2006;67(11):1942–1948. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000247042.15547.eb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of Persons by Dementia Status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Technical Paper #5. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sclan SG, Reisberg B. Functional assessment staging (FAST) in Alzheimer’s disease: reliability, validity, and ordinality. Int Psychogeriatr. 1992;4 Suppl 1:55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(6):808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black BS, Johnston D, Leoutsakos J, et al. Unmet needs in community-living persons with dementia are common, often non-medical and related to patient and caregiver characteristics. Int Psychogeriatr. February 2019:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S1041610218002296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woodman C, Baillie J, Sivell S. The preferences and perspectives of family caregivers towards place of care for their relatives at the end-of-life. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative evidence. BMJ Support Palliat Care. May 2015. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.America’s Long-Term Care Crisis: Challenges in Financing and Delivery. Bipartisan Policy Center. April 2014. http://bipartisanpolicy.org/library/americas-long-term-care-crisis/. Accessed July 26, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cost of Long Term Care | 2018 Cost of Care Report | Genworth; https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html. Accessed February 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, Skinner JS. The Burden of Health Care Costs for Patients With Dementia in the Last 5 Years of Life. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(10):729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, Kane RL. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: a meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai X, Temkin-Greener H. Nursing Home Admissions Among Medicaid HCBS Enrollees: Evidence of Racial/Ethnic Disparities or Differences? Med Care. 2015;53(7):566–573. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelley AS, Covinsky KE, Gorges RJ, et al. Identifying Older Adults with Serious Illness: A Critical Step toward Improving the Value of Health Care. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(1):113–131. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). National Plan to Address Alzheimer’s Disease: 2018 Update. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018:115 https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2018-update. [Google Scholar]

- 27.2012 HHS Poverty Guidelines. ASPE. https://aspe.hhs.gov/2012-hhs-poverty-guidelines. Published November 23, 2015. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 28.OASDI and SSI Program Rates & Limits, 2012. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/quickfacts/prog_highlights/RatesLimits2012.html. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 29.Laurence BK, Attorney. Federal Poverty Level Eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid Benefits - 2019. www.nolo.com. https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/federal-poverty-level-eligibility-medicare-medicaid-benefits.html. Accessed February 23, 2019.

- 30.Löwe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122(1-2):86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]