Abstract

Objective:

Adult patients are increasingly receiving care in pediatric emergency departments (PEDs), but little is known about the epidemiology of these visits. The goal of this study was to examine the characteristics of adult patients (≥ 21 years) treated in PEDs, and to describe the variation in resource utilization across centers.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional study examining visits to 30 PEDs (2012–2016) using the Pediatric Health Information System. Visits were categorized using All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups and compared between age cohorts. We used multivariable logistic models to examine variation in demographics, utilization, testing, treatment, and disposition.

Results:

There were 12,958,626 visits to the 30 PEDs over 5 years; 70,636 (0.6%) were by adults. Compared with children, adult patients had more laboratory testing (49% vs. 34%), diagnostic imaging (32% vs. 29%) and procedures (48% vs. 31%), and were more often admitted (17% vs. 11%) or transferred (21% vs. 0.7%) (p<0.001 for all). In multivariable analysis, older age, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, and private insurance were associated with decreased odds of admission in adults seen in PEDs. Across PEDs, the admission (7 to 25%) and transfer (6 to 46%) rates for adults varied.

Conclusions

Adult patients cared for at PEDs have higher rates of testing, diagnostic imaging, procedures, and admission or transfer. There is wide variation in the care of adults in PEDs, highlighting the importance of further work to identify the optimal approach to adults who present for care in pediatric centers

Keywords: pediatric emergency medicine, adult patients, transitions in care

Introduction

Pediatric emergency departments (PEDs) are required by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) to evaluate and stabilize all patients that present for treatment, regardless of age.1 Since enactment of EMTALA in the 1990s, adult visits to PEDs have been increasing.2 Adults represent a population outside the usual scope of practice for pediatric hospital staff. Almost 80% of PEDs report an age limit policy of 18 to 21 years,3 but most have exceptions to this cutoff, including patients with certain chronic conditions.3 Single center studies have shown that adult patients are often triaged to the highest acuity level,4 and adults with chronic pediatric conditions are more likely to be hospitalized and managed in the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU).5 However, there are limited data comparing the epidemiology of adult visits between pediatric centers.

The goals of this study were to describe the characteristics of adult patients presenting to PEDs, and to examine differences in resource utilization and disposition. We analyzed the data with two distinct populations in mind: 1) adults with a history of receiving care from the children’s hospital and 2) adults without an established relationship with the hospital (e.g. visitors or hospital employees).

Methods

Study design, setting, participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study examining PED visits to 30 pediatric hospitals in the United States using data from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), a comprehensive database which includes clinical and resource utilization for inpatient and ED visits. PHIS includes data from children’s hospitals. All included hospitals have an academic affiliation, but not all are free-standing children’s hospitals. The Children’s Hospital Association (CHA) administers and maintains the data and ensures data quality in partnership with hospitals.6 Data are de-identified before inclusion, and encrypted unique patient identifiers enable patients to be tracked across multiple visits.6 We used a 5-year study period (2012 through 2016) for examination of PED use at the visit level, with a look-back to 2007 for comorbidities. The adult cohort was defined as patients ≥21 years of age at the time of their ED visit, as most PEDs (64%) report using that age cutoff to define a pediatric visit.3 The Children’s Hospital Association Annual Benchmark Report was used to determine hospital inpatient bed capacity. The institutional review board at Boston Children’s Hospital determined this study to be exempt from review.

Exposures and Outcomes

We assessed hospital-level characteristics, including annual ED census, number, and proportion of visits for adults relative to total ED volume, and patient demographics including sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance type. Visits were categorized using the All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG, 3M).7 The APR-DRG are a classification scheme that classifies patients according to reason for treatment, severity and mortality risk.

The two primary outcomes were hospital admission at the study site and transfer to another hospital. The secondary outcomes included resource utilization at the ED visit: billed laboratory testing, diagnostic imaging, medications administered, and procedures performed (including EKGs). Billed services are assigned to a day of service in the database. Therefore, visit events were included in our study if they occurred on day 0 for an admitted patient who arrived to the ED prior to 6pm, on day 0 or day 1 for an admitted patient who arrived to the ED after 6pm (to include potential boarding time in the ED extending into the next day), or on any day for a patient discharged from the ED.

For each patient visit, we assessed prior ED utilization (defined by visits with a discharge from the ED) and hospitalizations at the study site within the 365-day period preceding the ED visit. The presence of complex chronic conditions (CCCs)8 was ascertained based on coding within the previous five years and included the index PED visit. PED disposition was coded as admitted at the study site, died, discharged, transferred, “against medical advice,” or “left without being seen” and other (e.g. unknown and not yet dispositioned).

Statistical analysis

Using standard descriptive statistics, we examined variation in PED testing, treatment, and disposition between adult and pediatric patients. Differences of those proportions were assessed with chi-squared tests. We used two multivariable mixed logistic regression models with random effects to account for hospital clustering to evaluate the association between patient and hospital characteristics and admission or transfer of adult patients. Models included age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance, CCC, prior ED visit to study site, prior hospitalization at the study site, ED volume and hospital size. To assess differences related to a history of receiving care from the children’s hospital we examined admission and transfer patterns for patients stratified by a history of hospitalization at the study site in the last year. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

There were 12,958,626 visits to the 30 PEDs over the 5-year period, of which 70,636 were among adult patients ≥ 21years (0.6% of all PED visits). Of the adult patients, 55.7% were aged 21–26 years, 26.9% were aged 27–40, and 17.4% were ≥ 41 years of age. Compared to children < 21 years of age, adults seen in the PED were more likely to have a CCC (21.1% vs 4.6%, p ≤.001) and to have been hospitalized at the study site over the preceding year (20.2% vs. 11.4%, p<0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1:

Demographic and visit characteristics by age group

| Age < 21 years | Age ≥ 21 years | |

|---|---|---|

| Visits, n | 12887990 | 70636 |

| DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Male, n(%) | 6789912 (52.7) | 25294 (35.9) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 4 (1,10) | 25 (22, 35) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n(%) | ||

| White | 4909614 (38.1) | 34500 (48.8) |

| Black | 3474151 (27.0) | 19072 (27.0) |

| Hispanic | 3406997 (26.4) | 11336 (16.0) |

| Other | 1097228 (8.5) | 5728 (8.1) |

| Insurance Type, n(%) | ||

| Public | 8382532 (65.5) | 30263 (43.9) |

| Private | 3687375 (28.8) | 25299 (36.7) |

| Other | 725187 (5.7) | 13378 (19.4) |

| 1 or more CCC, n(%) | 822878 (6.4) | 17604 (24.9) |

| ED visit in the last year n(%) | 5762540 (44.7) | 16021 (22.7) |

| Hospitalized in past year, n(%) | 1454611 (11.3) | 14320 (20.3) |

| VISIT CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Disposition, n(%) | ||

| Discharged | 11111746 (86.2) | 39374 (55.7) |

| Admitted | 1435593 (11.1) | 12168 (17.2) |

| Transfer | 92168 (0.7) | 14907 (21.1) |

| Died | 2106 (0.0) | 39 (0.1) |

| AMA/LWBS | 109020 (0.8) | 2253 (3.2) |

| Other | 137357 (1.1) | 1895 (2.7) |

| Any lab testing, n(%) | 4349996 (33.8) | 34501 (48.8) |

| Any diagnostic imaging, n(%) | 3744397 (29.1) | 22715 (32.2) |

| Any procedure, n(%) | 3918665 (30.4) | 33769 (47.8) |

| Top 5 Diagnoses (All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) | ||

| 1 | Infections of upper respiratory tract | Chest pain |

| 2 | Non-bacterial gastroenteritis |

Other factors influencing health status* |

| 3 | Contusion/other trauma to skin | Other musculoskeletal system diagnoses |

| 4 | Other skin disorders | Contusion/other trauma to skin |

| 5 | Other musculoskeletal system diagnoses | Abdominal pain |

Ex. altered mental status, malaise and fatigue, referral without treatment

Visit events and outcomes

Compared to children, adults were more likely to have laboratory testing (49% vs. 34%, p≤.001), diagnostic imaging (32% vs. 29%, p≤0.001), and procedures (48% vs. 31%, p≤0.001) performed, and were more often admitted to the pediatric hospital study site (17% vs. 11%, p≤0.001) or transferred (21% v. 0.7%, p≤0.001) from the ED [Table 1]. The five most common APR-DRGs are shown in Table 1. The 5 most common clinical billings codes for procedures for adults are shown in Appendix A.

In multivariable analyses of adults [Table 2], patient factors associated with increased odds of admission included the presence of a CCC (aOR 1.39; 95% CI: 1.28, 1.51) and any prior hospitalization at the study site (aOR 4.97; 95% CI: 4.52, 5.45). Older age, black race or Hispanic ethnicity, private insurance and at least one ED visit over the past year were associated with decreased odds of admission. Older age and black or Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with increased odds of transfer. Private insurance, prior ED visit, or past hospital admission were associated with decreased odds of transfer. CCC was not significantly associated with transfer disposition (Table 2).

Table 2:

Multivariable model for admissions and transfers from the PED among adult (≥21 year old) patients

| Admitted aOR (95% CI) |

Transferred aOR (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age Category | ||

| 21–26 | Ref | Ref |

| 27–40 | 0.60 (0.56, 0.65) | 3.04 (2.88, 3.2) |

| 41+ | 0.17 (0.14, 0.19) | 5.46 (5.16, 5.78) |

| Male sex | 1.62 (1.53, 1.72) | 0.85 (0.81, 0.89) |

| Rate/Ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | Ref |

| Black | 0.52 (0.48, 0.56) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.31) |

| Hispanic | 0.65 (0.59, 0.72) | 1.20 (1.12, 1.29) |

| Other | 0.55 (0.48, 0.63) | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) |

| Insurance Type | ||

| Public | Ref | Ref |

| Private | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) | 0.83 (0.79, 0.87) |

| Other | 0.38 (0.34, 0.42) | 0.92 (0.87, 0.97) |

| Any Complex Chronic Condition | 1.39 (1.28, 1.51) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) |

| ED utilization in the past year | ||

| 0 | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.97) | 0.61 (0.55, 0.66) |

| 2 | 0.69 (0.62, 0.78) | 0.42 (0.36, 0.5) |

| 3 | 0.46 (0.39, 0.55) | 0.41 (0.32, 0.52) |

| 4+ | 0.34 (0.3, 0.38) | 0.51 (0.42, 0.63) |

| Hospitalizations in the past year | ||

| 0 | Ref | Ref |

| 1 | 4.97 (4.52, 5.45) | 0.14 (0.12, 0.17) |

| 2 | 6.96 (6.18, 7.83) | 0.13 (0.1, 0.18) |

| 3 | 8.22 (7.15, 9.45) | 0.14 (0.1, 0.19) |

| 4+ | 15.43 (13.79, 17.26) | 0.10 (0.08, 0.13) |

| Annual ED Volume | ||

| 100K+ | 0.54 (0.23, 1.26) | 0.90 (0.68, 1.2) |

| 75–99K | 1.24 (0.56, 2.73) | 0.60 (0.45, 0.78) |

| 50–74K | 0.91 (0.44, 1.9) | 0.74 (0.58, 0.95) |

| <50K | Ref | Ref |

| Number of hospital beds | ||

| 500+ | 4.64 (1.7, 12.7) | 1.76 (1.25, 2.49) |

| 300–499 | 2.11 (0.96, 4.62) | 2.10 (1.62, 2.72) |

| 225–299 | 1.76 (0.81, 3.82) | 1.60 (1.24, 2.08) |

| <225 | Ref | Ref |

| Percentage of Adult ED Visits | ||

| <0.3% | 0.30 (0.14, 0.64) | 3.84 (2.96, 4.98) |

| 0.3–0.4% | 0.39 (0.19, 0.79) | 2.79 (2.18, 3.56) |

| 0.5–0.7% | 0.62 (0.32, 1.23) | 1.67 (1.33, 2.11) |

| >0.7% | Ref | Ref |

Prior hospitalization

Adults with a hospitalization in the past year accounted for 2% to 53% of adult patients at each site. For patients with a hospitalization in the past year, the rate of admission increased with increasing age, but there was no similar trend for transfers. Instead, the transfer rate increased with age for those without a hospitalization in the last year. [Online Appendix Figure B.1 and B.2].

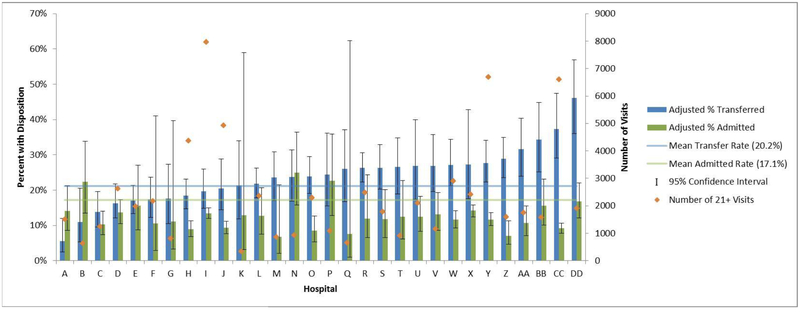

Hospital variation

Wide variation in adjusted admission (7 to 25%) and transfer (6 to 46%) rates for adult patients was seen across pediatric hospitals [Figure 1]. Large variation remained (16–62%) across the pediatric hospitals when we examined combined rates for admitted and transferred (“non-discharged”) patients. Hospital factors associated with increased odds of admission for adults included larger hospital size (aOR 4.64; 95% CI: 1.7, 12.7 for ≥ 500 inpatient beds compared with <225 inpatient beds). Presentation to an ED with lower proportions of adult visits was associated with decreased odds of admission [Table 2]. The increase in odds of transfer with older age was not explained by the decrease in odds of admission by hospital (Table 2, Online Appendix C).

Figure 1: Variation in admission and transfer rates for adult (≥21 years of age) patients between hospitals.

The left sided x-axis represents the percentage of adult patients, and the right sided x-axis represents the number of adult visits. The y-axis identifies each included hospital. The blue bars are the adjusted* percentage of adult patients who are transferred, with error bars representing the 95% confidence interval. The green bars are the adjusted percentage of adult patients who are admitted, with error bars representing the 95% confidence interval. Orange circles demonstrate the adult volume by center.

* Adjusted for model elements in Table 2

Discussion

We do not have information regarding ED visits or hospitalizations to non-PHIS hospitals. In addition, due to the structure of the PHIS database, we are unable to discriminate inpatient testing from ED testing for admitted patients, requiring us to rely on using data on testing from day 0 and day 1 to best account for ED utilization. We chose a conservative definition of patients receiving ongoing care at the children’s hospital, including only those with a hospitalization in the last year, which may have underestimated the number of adult patients with an existing relationship to the children’s hospital such as those who have only used the ED. We do not have the ability to separate out adult patients who were employees of or visitors to the children’s hospital from those who arrived in the pediatric ED for other reasons. We do not have clinician level data to assess the level of experience with adult patients and general emergency medicine among physicians at the study sites, or the ability to compare resource utilization for similar cases in non-pediatric EDs.

Adults patients accounted for approximately 1 in 200 visits to PEDs. Adult patients in the PED are more likely to have a complex chronic condition or prior hospitalization and have higher rates of testing, diagnostic imaging, procedures and admission than children. Overall, we found that the relative proportion of adult patients presenting to PEDs is low, but the resource utilization is high. With increasing rates of adult presentations to PEDs,2 ensuring high quality care for this population is of key importance.

There is a paucity of literature evaluating hospitalization and transfer patterns of adults presenting to PEDs. A limited study excluding patients with injury, psychiatric or substance abuse diagnoses, found that 22% of adult patients were transferred9 and these transfers were associated with emergent diagnosis, higher triage acuity, and age 45–64 years.9 These findings are similar to the transfer rate in our data of 21% and the association of higher likelihood of transfer with increasing age. The decreasing odds of admission with increasing age within the adult group may be representative of the eventual transition of these patients to adult care providers, or may reflect that these older patients are likely to be hospital employees or visitors without established care at the pediatric facility. Increasing frequency of ED visits in the prior year was associated with decreased odds of both admission and transfer, suggesting there may be a population of higher utilizing, and frequently discharged, adult patients who are worthy of further study. The rates of admission and transfer from the PED for adult patients varied widely across pediatric hospitals, and appeared to be largely driven by variation in disposition for patients with a prior hospitalization at that site. This is particularly important because prior studies have suggested that patients with an existing relationship with the hospital make up a meaningful portion of the adult patients. One study found that approximately 20% of adult patients in the PED were referred there by a primary care or specialist provider,10 and another found that adult patients with chronic pediatric disorders accounted for 44% of the adult volume to the PED.5

Prior studies of socioeconomic status and transfer patterns have mixed results. Pediatric trauma patients are more likely to be transferred to a pediatric trauma center if they have public insurance.11 For non-injured pediatric patients, however, uninsured and self-pay patients were more likely to be transferred, and the odds of transfer were similar between those with Medicaid and private insurance.12 A single center study focusing on adult patients presenting to the PED found no association between insurance and transfer.9 In our study, black race was associated with decreased odds of admission and increased odds of transfer, and public insurance was associated with increased odds of admission or transfer. Adults with public insurance at pediatric centers may represent a population with complex comorbidity and disability who are able to remain on Medicaid, and therefore would be less likely to be discharged (and more likely to be admitted or transferred). More research is needed to understand the complex interplay of socio-economic factors in making transfer decisions.

Although there has been a great deal of emphasis on preparing general EDs to care for complex, transition-aged, pediatric patients,13 our data emphasize the importance of PEDs being prepared to care for adult patients, both those with medical complexity who may have a preexisting relationship to the hospital and those who present for other reasons. Additional work is needed to understand the drivers of variation in adult patient care in the PED, including different health system organizational structures, and to assess the relationship between variation and patient outcomes. The ultimate goal is to identify the optimal approach for adults who present for care in pediatric centers. Potential areas for investigation include electronic vital sign triggers with adult values to avoid missing serious illness or sepsis in this age range, clinical protocols for the treatment of common adult emergencies (chest pain) with expedited transport, and phone or telemedicine consultation with adult EM providers. Similar medicine-pediatrics consult services are being used for the care of adult patients in some inpatient pediatric hospital settings.14

Supplementary Material

What’s New:

Compared with children, adult patients in pediatric EDs, have higher rates of testing, imaging, procedures, admission and transfer. There was wide variation in adjusted admission (7 to 25%) and transfer (6 to 46%) rates for adult patients between pediatric hospitals.

Financial support:

Dr. Aronson is supported by CTSA grant number KL2 TR001862 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Freedman is supported by the Alberta Children’s Hospital Professorship in Child Health and Wellness. There is no external funding for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (Accessed 1/30/2018, at https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EMTALA/.)

- 2.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW. Adult patient visits to children’s hospital emergency departments. Pediatrics 2003;111:1268–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dobson JV, Bryce L, Glaeser PW, Losek JD. Age limits and transition of health care in pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007;23:294–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little WK, Hirsh DA. Adult patients in the pediatric emergency department: presentation and disposition. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014;30:808–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonnell WM, Kocolas I, Roosevelt GE, Yetman AT. Pediatric emergency department use by adults with chronic pediatric disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:572–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuman MI, Alpern ER, Hall M, et al. Characteristics of recurrent utilization in pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1025–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.All Patinet Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs): Methodology Overview. 3M Health Information Systems, 2003. (Accessed 2/15/18, at https://www.hcupus.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf.)

- 8.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC pediatrics 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kornblith AE, Foster AA, Cho CS, Wang RC, Jaffe DM. Patient Factors Associated With the Decision to Transfer Adult Patients From a Pediatric Emergency Department For Definitive Care. Pediatr Emerg Care 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rhine T, Gittelman M, Timm N. Prevalence and trends of the adult patient population in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:141–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang NE, Saynina O, Kuntz-Duriseti K, Mahlow P, Wise PH. Variability in pediatric utilization of trauma facilities in California: 1999 to 2005. Ann Emerg Med 2008;52:607–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Y, Natale JE, Kissee JL, Dayal P, Rosenthal JL, Marcin JP. The Association Between Insurance and Transfer of Noninjured Children From Emergency Departments. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2017;69:108–16.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murtagh Kurowski E, Byczkowski T, Grupp-Phelan JM. Comparison of emergency care delivered to children and young adults with complex chronic conditions between pediatric and general emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:778–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinnear B, O’Toole JK. Care of Adults in Children’s Hospitals: Acknowledging the Aging Elephant in the Room. JAMA pediatrics 2015;169:1081–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.