Abstract

Angiogenesis is a critical, fine-tuned, multi-staged biological process. Tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling are the building blocks of sprouting angiogenesis. Accumulated evidences show that tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling are regulated by a variety of physical, chemical and biological factors, especially the interaction among multiple genes, their products and environments. The classic Notch-VEGFR, Slit-Robo, ECM-binding integrin, semaphorin and CCN family play important roles in tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling. In this review, we outline the progress and prospect in the mechanism and the roles of the various molecules and related signaling pathways in endothelial tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling. In the future, the regulators of tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling would be the potential markers and targets for angiogenesis.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Endothelial cells, Tip-stalk cell selection, Tip-stalk shuffling, Signaling pathway

Endothelial cells (ECs) remain quiescent in most healthy adults. Angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels occurs under many physiological conditions, such as embryo development, and pathological conditions, such as chronic inflammation, certain immune reactions and cancers (Potente et al. 2011). The growth of vascular system involves tip cell selection, sprout formation, tip cell migration, stalk cell proliferation, and ultimately vascular stabilization. The distal end of each sprout contains a specialized EC, termed tip cell. Tip cells are motile, invasive and highly polarized with a large number of long filopodial protrusions which can extend, lead and guide endothelial sprouts, so navigation is just the main job of tip cells (De Smet et al. 2009). Tip cells sense the attractive or repulsive cues by filopodia, then translate signals into the process of adhesion (front) and de-adhesion (rear), and ultimately lead to cell movement (Carmeliet and Jain 2000). Stalk cells trail tip cells (De Smet et al. 2009), proliferate, elongate the sprouts, form lumens, and construct blood circulation under suitable conditions. But stalk cells do not extend filopodia. Tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling are basic events of angiogenesis regulated by the balance between a variety of pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors and their downstream signaling network (Carmeliet and Jain 2000). During sprouting, ECs take a series of changes, and compete for the leading positions; previously inhibited stalk cells can be relieved from their inhibition and become new tip cells. Thus, the specification of endothelial tip and stalk cells does not represent permanent cell fate decisions, but dynamic phenotype specification in flux.

Tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling during angiogenesis

The phenotypes of tip and stalk cell are remarkably transient and exchangeable. Tip and stalk cells shuffle and compete for the leading tip positions (Jakobsson et al. 2010). During angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs)/Notch signaling pathway performs continuous re-evaluation and many other signaling pathways are identified to participate the regulation of tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling (Moya et al. 2012). ECs may change in metabolism, gene expression, and phenotype, responding to the extracellular signals (Kim et al. 2011). A cascade of events is involved in angiogenesis, including tip cell selection, sprout formation, stalk cell proliferation, and ultimately vascular stabilization (Belair et al. 2016). The tip and stalk cell markers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Differentially expressed genes/markers between endothelial tip and stalk cells

| Stalk-like | Ackr1, Aqp1, C1qtnf9, Cd36, Csrp2, Ehd4, Fbln5, Hspb1, Ligp1, Il6st, Jam2, Lgals3, Lrg1, Meox2, Plscr2, Sdpr, Selp, Spint2, Tgfbi, Tgm2, Tmem176a, Tmem176b, Tmem252, Tspan7, VEGFR1, Vwf |

| Tip-like | Adm, Ankrd37, C1qtnf6, Cldn5, Col4a1, Col4a2, Cotl1, Dll4, Ednrb, Fscn1, Gpihbp1, Hspg2, Igfbp3, Inhbb, Jup, Kcne3, Kcnj8, Lama4, Lamb1, Lxn, Marcksl1, Mcam, Mest, N4 bp3, Nid2, Notch4, Plod1, Plxnd1, Pmepa1, Ptn, Ramp3, Rbp1, Rgcc, Rhoc, Trp53ill, Unc5B, VEGR2, VEGFR3 |

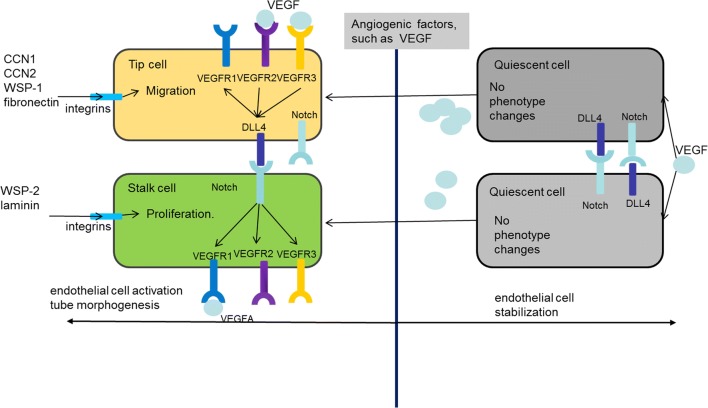

Tip selection: Competition of leading positions

During angiogenic sprouting, ECs migrate and compete with each other for the leading tip positions (Bentley et al. 2008). Tip cells are induced and guided by extracellular microenvironment and the expression level of VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) on cell surface (Fig. 1) (De Smet et al. 2009). The ECs with higher VEGFR2 and lower VEGFR1 levels have a better chance to take and maintain the leading positions; VEGFR3, which is highly expressed in tip cells, is induced and activated by extracellular VEGFC (Bentley et al. 2008). Especially, VEGFR3 down-regulates VEGFR2 pathway, and VEGFR levels have a marked effect on the upstream of Notch by regulating delta-like 4 (Dll4) levels. The tip cell selection relies on Dll4-Notch signal pathway, which regulates the lateral inhibition and competitive interactions among the tip cells and stalk cells. Compared with stalk cells, tip cells express higher levels of Dll4, and are more susceptible to the alteration of Notch, the receptor of Dll4. As extracellular VEGF binds to VEGFR2 or VEGFR3 on the membrane, tip cells or tip-to be cells receive more VEGF, and then express higher level of Dll4. Notch signaling pathway on adjacent cell membrane is strongly activated; further, the adjacent cells express higher level of VEGFR1 and lower level of VEGFR2 and VEGFR3 (Benedito et al. 2012). As a result, adjacent cells keep low level of Dll4, and finally turn to stalk cells. With low level of Dll4, stalk cells cannot activate Notch on the tip cell membrane. Thus, tip cells maintain higher VEGFR2 and lower VEGFR1 in leading positions (Benedito et al. 2012). Notch affects the expression of VEGFRs, while VEGFR activity affects expression of Dll4, the ligand of Notch. Therefore, the two pathways integrate into an intercellular feedback loop (Geudens and Gerhardt 2011). VEGF-VEGFR-Dll4-Notch-VEGFR feedback loop patterns ECs into tip and stalk cells (Weavers and Skaer 2014). Activated Notch signaling pathway stabilizes tip cells and inhibits excessive conversion into tip cells; in the absence of Notch signaling pathway, stalk cells are no longer specified and become tip cells due to the dysfunction of Notch-VEGFR feedback-mediated lateral inhibition (Carlier et al. 2012).

Fig. 1.

Tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling

Cell motility

ECs migrate and elongate the sprouts primarily guided by lamellipodia and filopodia, which detect the environment (De Smet et al. 2009). Filopodia and lamellipodia are highly dynamic. They can generate from cell membrane within minutes after receiving signals from the microenvironment (Ridley et al. 2003). Lamellipodia are very short, and contain a highly branched network of actin. The action of lamellipodia promotes the membrane movement in the direction of migration (Ridley et al. 2003). Filopodia are composed of long spiky plasma membrane. They contain tight parallel bundles of filamentous actin (F-actin), Filopodia usually extend from lamellipodia and primarily explore and perceive the local signals (Lebrand et al. 2004). Attractive signals induce F-actin polymerization and filopodia extension. Filopodia and lamellipodia also adhere the extracellular matrix (ECM) and form focal adhesions, which bridge the cytoskeleton and ECM. The focal adhesions work as anchor points. Then stress fibers of actin/myosin filaments pull the cell toward the anchor points and cells finally move forward (Lamalice et al. 2007). Main steps of endothelial cell motility are as follows: ECs are activated by stimulation; filopodia determine the moving direction; lamellipodia form protrusions, extend the cell body, and the protrusions attach to ECM by the focal adhesion; stress fibers mediate cell body contraction, move forward and release rear (Prokopiou et al. 2016).

Tip stalk shuffling

Tip stalk shuffling is the process that the tip cell is dynamically challenged and replaced by migrating cells from the stalk region (Carmeliet et al. 2009). When stalk cells are not the neighbors of tip cells and receive no inhibitory signal from tip cells, stalk cells would replace tip cells whereas tips cell turns back to the basement position of the sprout and turn to stalk cells. VEGF-C activates VEGFR-3 in tip cells to reinforce Notch signaling, which contributes to the tip to stalk conversion of ECs at fusion points of vessel sprouts (Tammela et al. 2011). Notch signaling flux in individual cells results in differential VE-cadherin turnover and junctional-cortex protrusions, so eventually drive tip stalk shuffling (Bentley et al. 2014). The dynamic position shuffling depending on the VEGF–Notch feedback promotes reiterative sprouting and branching and thus robust network formation during angiogenesis (Bentley et al. 2008).

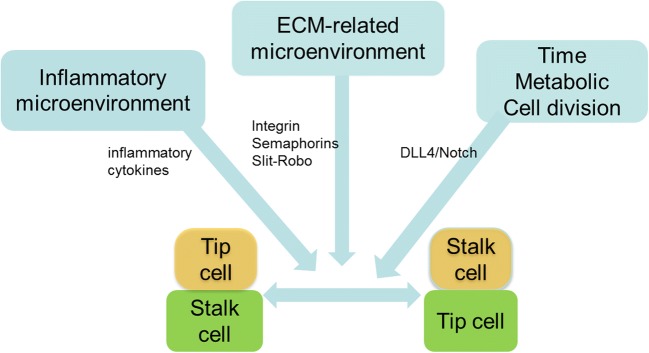

Influencing factors of tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling during angiogenesis

Tip and stalk cells shuffle, and tip cells further fuse a lumen, and finally form a vascular network (Toomey et al. 2009). A number of factors and signaling pathways have been involved in tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Influencing factors of tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling

Microenvironment

Angiogenesis involves the interaction between ECs and the surrounding environment, such as myeloid cells and vascular pericytes. In most vascular beds, ECs locate on the basement membrane (Delgado et al. 2011). In the complex three-dimensional environment in vivo, ECs are subject to a variety of physical, chemical and biological factors (Lamalice et al. 2007). In response to angiogenic cues, ECs loosen their cell-cell junctions and activate proteases that degrade the surrounding basement membrane (Carmeliet and Jain 2011). Extensively invasive and motile behavior is acquired to initiate new blood vessel sprouting (Herbert and Stainier 2011). The stromal cells, such as lymphatic vessels, activated fibroblasts, macrophages, and other immune cells, are also part of the blood vessel microenvironment. Cells in microenvironments release a series of soluble factors induce myeloid cells to mobilize, home, and differentiate into macrophages or neutrophils. In this dynamic process, the ligands and receptors on EC surface recognize each other. The interactions between ECs and microenvironment regulate their association with perivascular cells or macrophages, and also help determine their fate as tip cells or stalk cells (Weis and Cheresh 2011). There are too many components in the microenvironment, so the computational model is developed to investigate them together (Weinstein et al. 2017).

Time

In addition to the lateral inhibition determines cell fate (Sjoqvist and Andersson 2017), new models are proposed to supplement. Asymmetric division generates daughters of distinct size (Costa et al. 2016). The larger distal daughters will inherit more VEGFR activity and VEGFR2 mRNA levels to maintain tip Identity. Time may also be an important factor (Costa et al. 2016). There is a stable intermediate state between the tip and stalk cells, which external (neighboring DLL4) cooperate with the internal cellular factors in regulating the time to move away from this intermediate state and determining tip/stalk fate (Venkatraman et al. 2016).

Metabolic pathways

Angiogenesis has been traditionally studied by focusing on the balance between pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic signals, but metabolism is receiving more attention now (Eelen et al. 2018). Nevertheless, glycolysis, one of the major metabolic pathways that convert glucose to pyruvate, is required for the phenotypic switch from quiescent to activated ECs. During vessel sprouting, the glycolytic activator PFKFB3 (6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-3) promotes vessel branching by rendering ECs more competitive to reach the tip of the vessel sprout (De Bock et al. 2013), while fatty acid oxidation selectively regulates proliferation of endothelial stalk cells (Schoors et al. 2015). Glutamine is another source of nutrients for ECs. The majority of TCA carbons and nitrogen in ECs derive from glutamine (Kim et al. 2017). Glutaminase 1 (GLS1) promotes competitiveness to obtain the tip position (Huang et al. 2017). These studies show that metabolic pathways in ECs regulate vessel sprouting (Cantelmo et al. 2015).

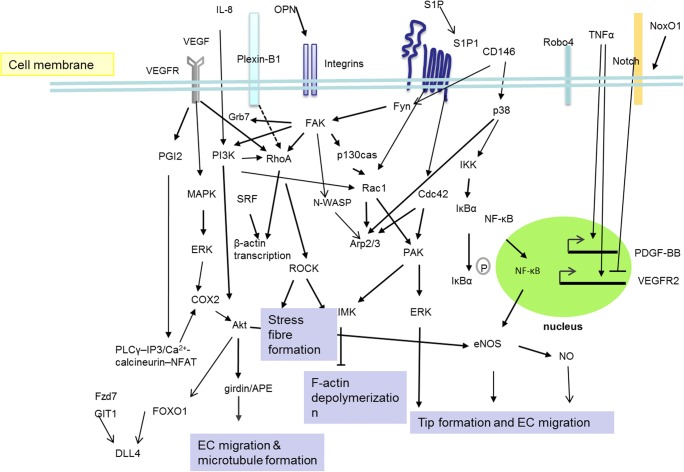

Key signaling pathway network in tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling

As receptors receive extracellular signals, signals are transduced through cascade amplification. In the processes of tip-stalk cell selection and shuffling, the regulatory pathways are connected to form a sophisticated network (Fig. 3). The related pathways will be introduced from extracellular to intracellular.

Fig. 3.

The signaling pathways are connected to form a sophisticated network to regulating tip selection during angiogenesis

Inflammatory cytokines pathways

Inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and bradykinin, induce tip cell phenotype (Eelen et al. 2013). Brief exposure to tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) is enough to induce performing tip cell phenotype and the expression of tip cell markers platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB) and VEGFR2, therefore helps guide angiogenic sprouting (Zecchin et al. 2017). The inflammatory cytokine TNF-α up-regulates Jagged1, however down-regulates Dll4 transcript levels (Sainson et al. 2008). Interleukin-8(IL-8), a chemotactic and inflammatory cytokine, belongs to the CXC subfamily. IL-8 not only induces cell membrane ruffles and the extension of lamellipodia, but also increases actin stress fibers which both suggest tip cell fate (Lai et al. 2011). The activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) - Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1(Rac1)/ Ras homolog family member A (RhoA) pathway plays an important role in IL-8-induced tip selection (Lai et al. 2011). Ligand Cxcl12a and the chemokine receptor CXCR4 are critical in controlling Notch-dependent angiogenesis (Pitulescu et al. 2017);

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is an anti-inflammatory phospholipid derivative with angiogenic properties and chemotaxis. It is also involved in the formation of lamellipodia on ECs. S1P is released from activated platelets, and functions via binding to S1P-G protein-coupled receptor (S1P1). S1P1 signaling is involved in the translocation of Arp2/3 complex. Arp2/3 complex translocates from intracellular to the migratory edge and leads to the formation of lamellipodia. This process relies on cell division control protein 42 (Cdc42) and Rac1 activation (De Smet et al. 2009). Cell proliferation, inflammation, and angiogenesis are mediated through bioactive S1P binding to specific GPCRs and some other less well-characterized intracellular targets. Ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) proteins, a family of adaptor linking the cortical actin cytoskeleton to the plasma membrane, are critical regulators of cell morphology and motility (Adada et al. 2015).

Notch-VEGFR pathway

Notch pathway plays the most important role in regulating tip and stalk cell selection, shuffling, and the number of tip cells in angiogenesis (Xu et al. 2014). The role of Notch signaling is to repress a tip cell identity. Notch signaling inhibits VEGFR2 expression indirectly through inducing HEY2, and activation of Notch induces VEGFR1 transcription and VEGFR1 protein production (Xu et al. 2014). Notch signal also changes the balance of EC membrane receptors expression in response to extracellular signals (Kofler et al. 2011).

VEGF is one of the vital factors affecting tip cell selection. In addition to the effects described above, VEGF also has other features. The VEGF family consists of only a few members and VEGFA is the main component, and it stimulates angiogenesis in health and disease by signaling through VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2, also known as FLK1) (Ferrara 2002). VEGFA isoforms have a spatial concentration gradient in the matrix, which promotes the tip cells filopodia extension induced by chemotaxis (Adams and Alitalo 2007). During retinal angiogenesis, identification and function of tip cells require the appropriate expression and location of VEGFR1, VEGFR2 and VEGFR3. Reduced VEGFR2 in retina decreases vascular density (Tammela et al. 2008), characterized as the lower number of ECs with filopodia extending, suggesting the loss of tip cells (Gerhardt et al. 2003). In contrast, reduced VEGFR1 increases the number of tip cells (Bentley et al. 2008). In activated vascular endothelium, VEGFR3 is confined to the extending filopodia of tip cells. Blocking VEGFR3 reduces the number of sprouts and branch points, as well as EC proliferation (De Smet et al. 2009). VEGF signaling via VEGFR2 enables tip cell formation, whereas Dll4 signaling induces stalk cells. VEGFR2 is required for the sprouting of endothelial cells that display low Notch activity (Zarkada et al. 2015). VEGFR3, the main receptor for VEGFC, was modulated by Notch (Benedito et al. 2012). VEGFR3 cannot rescue the angiogenic sprouting associated with loss of Notch signaling. There is higher NRP1 on tip cells than on stalk cell. After inhibition of Notch signaling, NRP1 is strongly up-regulated (Hellström et al. 2007). NRP1 is a co-receptor for VEGFR2 and positive modulator of VEGFR2 signaling. Genetic mosaic analysis shows that NRP1-positive ECs reach the tip cell position compared with NRP1-negative ECs in chimeric vessel sprout (Fantin et al. 2013). NRP1 flips into forming rapid VEGFR2/NRP1 complex in the same cell, regulates VEGFR2 signaling, but suppresses angiogenesis on different cells (Koch et al. 2014). NRP1 consumption decreases cell migration by suppressing the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (Li et al. 2016). Ca2+ oscillations depend upon VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2) and VEGFR3 in ECs budding from the dorsal aorta (DA) and posterior cardinal vein, respectively. Thus, visualizing Ca2+ oscillations allowed us to monitor EC responses to angiogenic cues VEGFR-dependent (Yokota et al. 2015).

The ligands of Notch include Dll1, 3, 4 and Jagged1, 2. They play important but different roles in angiogenesis. Inhibition of DLL-class or Jagged class Notch signaling differentially regulated VEGFR-1 expression. Jagged class inhibitors increased VEGFR-1 transcripts, whereas DLL-class inhibitors decreased VEGFR-1 transcripts (Kangsamaksin et al. 2015). It is known that the difference in blockers affects the expression level of soluble protein (sVEGFR-1/sFlt-1) (Kangsamaksin et al. 2015). The key role of Notch-Jagged signaling in mediating differences between physiological and pathological angiogenesis can be used in novel therapeutic approaches, such as developing decoys that can selectively target Jagged /NOTCH (Kangsamaksin et al. 2014). Such an attempt may provide a viable and safer alternative to targeting tumor angiogenesis (both via Delta and Jagged) (Boareto et al. 2015).

The new regulators of Notch pathway are summarized as follows. The transmembrane protein Tmem230a is a novel regulator of angiogenesis by cooperating with Notch signaling pathway. Self-regulation of Tmem230a expression is sufficient to rescue improper number of endothelial cells induced by the Dll4/Notch pathway in zebrafish (Carra et al. 2018). Fzd7 (frizzled-7) may participate to the lateral inhibition for tip/stalk cell through regulating expression of Dll4 in tip cells (Peghaire et al. 2016). Fzd7 controls Notch signaling through the regulation of Jagged1 and Dll4 expression by activation of β-catenin (Peghaire et al. 2016). Synaptojanin-2 binding protein (SYNJ2BP) interacts with the PDZ binding motif of DLL1 and DLL4, but not with the Notch ligand Jagged-1. SYNJ2BP is preferentially expressed in stalk cells, enhances DLL1 and DLL4 protein stability, promotes Notch signaling in endothelial cells and induces expression of the Notch target genes (Adam et al. 2013). It inhibits the expression of genes enriched in tip cells and impaired tip cell formation. SYNJ2BP as a novel inhibitor of tip cell formation executes its functions predominately by promoting Delta-Notch signaling (Adam et al. 2013). BMP2 and BMP6 balance stalk vs. tip cell competence through differential BMP receptor-dependent Notch signaling pathways (Benn et al. 2017). FOXO1 binds to the enhancer in intron 3 of DLL4, then PI3K/AKT regulates ERK-dependent DLL4 activation by controlling FOXO1 activity. FOXO1 inhibits ERK signaling through related target genes. FOXO1 inhibits VEGF-Notch-dependent tip cell formation by inhibiting DLL4 in response to VEGF expression (Dang et al. 2017). Another Inhibitor of Dll4-Notch1 Signaling is G protein-coupled receptor-kinase interacting protein-1 (GIT1) (Majumder et al. 2016). GIT1 regulates the stalk cell phenotype through enhancing Dll4 expression and Notch1 signaling. Lack of GIT1 associates with tip cell formation decrease and retinal sprouting angiogenesis impair. Notch signaling affected by NADPH oxidase organizer 1 (NoxO1) (Brandes et al. 2016). Lack of NoxO1 attenuates Notch signaling, promotes tip cell numbers and increases angiogenesis (Brandes et al. 2016). Notch signaling negatively regulates Isl2a expression, while Isl2a positively regulates VEGFR3, a VEGF-C receptor repressed by Notch (Lamont et al. 2016). Thus Isl2a may act as an intermediate between Notch signaling and VEGF singaling.

Slit-Robo pathway

Slit-Robo pathway has many diverse functions including axon guidance and angiogenesis. Slit refers to a secreted protein and Robo refers to its transmembrane protein receptor. Slit2 can promote or inhibit angiogenesis, depending on the condition of the molecule (Worzfeld and Offermanns 2014). The interaction of SLIT2/ROBO1/ROBO4 to control angiogenesis involves the endothelial receptor Robo4 (R4), which interacts with another protein and activates an antiangiogenic pathway that counteracts VEGF downstream signaling (Gimenez et al. 2015).

Robo4 is the only EC-restricted member in Roundabout gene family, and is an effective tumor endothelial marker (Yoshikawa et al. 2013). The function of Robo4 in angiogenesis still remains controversies (Herbert and Stainier 2011). The conjectures are mainly divided into two categories: in a tip cell, unligated Robo4 stimulates filopodia formation, cell migration and angiogenesis; whereas Robo4 binds Unc5B on adjacent phalanx cells, leading to stabilization of the vasculature (Sheldon et al. 2009). Endothelial transmembrane protein Unc5B is highly expressed on tip cells and is identified as the ligand of Robo4. When Robo4 binds Unc5B on an adjacent endothelial cell, Unc5B releases an anti-migratory stabilizing signal (Koch et al. 2011). The function of Robo4 may be context-dependent.

Semaphorin pathway

Semaphorins are membrane-bound or diffusible factors that regulate key cellular functions and are involved in cell-cell communication. Most of the effects of semaphorins are mediated by a family of transmembrane receptors known as plexins. Plexins belong to the c-Met family, but lack an intrinsic tyrosine kinase domain. Intriguingly, activated plexins can transactivate receptor tyrosine kinases, such as MET, VEGFR2, FGFR2, and ERBB2, and lead to distinctive effects in a cell-context-dependent manner (Tamagnone 2012). Different semaphorins have different effects on ECs (Worzfeld and Offermanns 2014). Activation of plexin D1 on ECs by full-length SEMA3E inhibits tumor angiogenesis. Other semaphorins, such as SEMA3A, SEMA3B, SEMA3D and SEMA3F also exert anti-angiogenic effects by inhibiting integrin function. In contrast to the class 3 semaphorins, SEMA4D, SEMA5A and SEMA6A promote angiogenesis. Most semaphorins source from cancer cells. In addition to cancer cells, tumor-associated macrophages serve as a source for SEMA4D. But SEMA3A and SEMA6A come only from ECs during tumor angiogenesis (Segarra et al. 2012). Activation of Plexin-B1 by SEMA4D promotes angiogenesis through RhoA and ROK by regulating the integrin-dependent signaling networks that result in the activation of PI3K, Akt and NF-kappaB (Basile et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2011). So semaphorins may have an influence on VEGFRs and further influence cell fate.

ECM-integrin pathway

ECM components, such as laminin, fibronectin and collagen, interact with integrins, and lead to the tip formation. Integrin induces cytoskeletal rearrangements, and different integrin has different effects; for instance, α5ß1 and αvß3 (both receptors of fibronectin) differentially regulate activation of Cofilin and migration (Fukushi et al. 2004). Ligation of α2β1 and α6β1 integrins, as a receptor of laminin, induces the Notch pathway, and plays a role in tip-stalk cell selection (Estrach et al. 2011).

Matricellular proteins

Osteopontin (OPN), a multifunctional glycoprotein, regulates bone remodeling. OPN is an alphavbeta3 integrin ligand which involves in angiogenesis (Rao et al. 2013). The biological activity of OPN on endothelial cell migration is controlled by its phosphorylation status (Poggio et al. 2011). The ECM-associated ligands can lead to constantly VEGFR2 polarization in ECs. Then the receptors can relocate to closely contact with ligand-enriched matrix. However, the relocation of VEGFR2 almost cannot do without lipid raft integrity and activation of integrin β3 pathway (Ravelli et al. 2015). Integrin α5β1 participates in the activation of both VEGFR-3 and its downstream PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Zhang et al. 2004). The relationship between VEGFR-2 and integrin β3 appears to be synergistic, because VEGFR-2 activation induces integrin β3 tyrosine phosphorylation, which, in turn, is crucial for VEGF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 (Mahabeleshwar et al. 2007).

CCN proteins (CYR61/CCN1, CTGF/CCN2, NOV/CCN3, and WISP1/CCN4, WISP2/CCN5, WISP3/CCN6 are a family of secreted matricellular proteins implicated in major cellular processes such as endothelial cell growth, migration, differentiation (Henrot et al. 2018). CCN proteins can interact with growth factors such as VEGF to promote angiogenesis (Kubota and Takigawa 2007). Among them, CCN1, 2, 3 angiogenesis inducers play an important role in vascular development and maintenance (Jun and Lau 2011). Given their complex functions, Table 2 is to illustrate their role in angiogenesis.

Table 2.

Functions and bindings of CCN family

| Model | Phenotype | Bindings | Pathway | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCN1 | Vascular smooth muscle | Migration | Integrin α6β1 and αvβ3 | Intracellular PDGF-ERK, JNK signals, integrin/ focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling (Zhang et al. 2015) |

| CCN1 | HUVEC | Migration | Integrin αvβ3 | AMP3 (Park et al. 2015) |

| CCN1 | Human coronary arterial endothelial cells | Apoptosis | – | TNF-α, CCN1, P53, NF-κB pathway (Zhang et al. 2016) |

| CCN1 | Retinal vascular development | Proliferation suppression of tip cell formation | Integrin β1 | Src homology 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-1 (SHP-1) VEGFR2, and Dll4 (Chintala et al. 2015) |

| CCN2 | Atherosclerosis | Adhesion, migration, proliferation, | Integrin αvβ3 | - (Schober et al. 2002) |

| CCN3 | Endothelial cells | adhesion and migration | Integrin α6β1 and αvβ3 | - (Chen and Lau 2009) |

| WSP-1 | Ovine squamous-cell carcinoma (OSCC) | Angiogenesis | integrin αvβ3 | Integrin αvβ3/FAK/c-Src, EGFR/ERK and FAK/c-Src signaling pathway (Chuang et al. 2015) |

| WISP-1 | Human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells | VEGF-C–dependent lymphangiogenesis | – | Inhibiting miR-300 (Lin et al. 2016) |

| WSP-1 | osteosarcoma | VEGF-A expression | – | Inhibiting miR-381 and FAK/JNK/HIF-1alpha signaling pathways (Tsai et al. 2017) |

| WSP-2 | endothelial cells | Antiangiogenesis | – | Matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP14) (Butler et al. 2017) |

| WSP-3 | Chondrosarcoma | VEGF-A expression and angiogenesis | – | Inhibiting miR-452 via the c-Src and p38 pathways (Lin et al. 2017) |

Intracellular network

VEGF activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways, inducing EC proliferation and migration (Fish et al. 2017). ERK is a specific effector of VEGFA signaling (Shin et al. 2016), and ERK activity could be a novel marker to determine the activation of cells in angiogenesis (Nagasawa-Masuda and Terai 2016).

Different signaling cascades converge to small GTPases activation to regulate filopodia and lamellipodia formation of ECs. Rho small GTPases have been identified as a key molecule of cell migration and morphogenesis (De Smet et al. 2009). It regulates filopodia and lamellipodia formation. RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42 are activated in response to various membrane receptors, including tyrosine kinase receptors and G protein-coupled receptors. Cdc42 and Rac1 regulate formation of filopodia and lamellipodia through activating PAK; RhoA promotes stress fibers formation via Rho-associated serine-threonine protein kinase (ROCK), and facilitates cell adhesion and migration. PAK and ROCK activate LIM Kinase (LIMK), and block F- actin depolymerization. Activated Cdc42 and Rac1 interact with the WASP-Arp2/3 complex and induce F- actin branching. In response to VEGF, Cdc42 triggers filopodia formation and regulates cell polarization through microtubule, whereas Rac1 and PAK modulate lamellipodia formation (De Smet et al. 2009).

Once filopodia begin to extend, it interacts with ECM components via integrin, such as laminin, fibronectin and collagen, lead to the formation of focal adhesions (Fischer et al. 2018). FAK is an important regulator of this process. There are many studies showing that integrin promote cell migration through FAK. FAK downstream signaling pathway is also involved in cell migration. One characterized pathway is via FAK/Src complex, in combination with p130cas phosphorylation (Zhao and Guan 2011). The activation of Src induces the changes of actin cytoskeleton and cell migration (Kerbel 2008). Disruption of FAK combining with Src or p130cas prevents phosphorylation of p130cas at multiple sites and reduces cell migration. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p130cas associates with the proteins containing SH2 domain, such as Crk. Cas/Crk complex plays a key role on membrane ruffling and cell migration through dedicator of cytokinesis 180(DOCK180) and Rac.. The activated PI3K stimulates cell migration through the downstream effector Rac. PI3K is a key regulator of cortical actin and lamellipodia. FAK binding with growth factor receptor-bound protein 7(Grb7) and Grb7 phosphorylation are important for stimulation of cell migration. FAK/PI3K and FAK/Grb7 complexes regulate FAK on cell migration coordinately. FAK also acts on the Rho subfamily of small GTPases, modulates polymerization and depolymerization of actin cytoskeleton, and regulates cell migration (Zhao and Guan 2011). On the other hand, PI3K also plays a role in maintaining cell polarity and deciding cell migration. Akt is a serine / threonine kinase, one of the major downstream effectors of PI3K (Sheng et al. 2009), is involved in the phosphorylation of girdin/ Akt phosphorylation enhancer (APE), and promotes the formation of microtubule (Kitamura et al. 2008). Akt phosphorylation activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and promotes tip cell selection in response to VEGF gradient (Dimmeler and Zeiher 2000). Rho GTPase and the feedback loop of PI3K integrate and amplify signals, and both are necessary for cell migration. In addition, FAK phosphorylates N-WASP, a key downstream effector of Cdc42, increases the cytoplasmic localization, promotes activation of Arp2/3 complexes, and facilitates actin polymerization in front of migrating cells (Zhao and Guan 2011).

CD146 associates with proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Fyn to phosphorylate FAK, rearranges actin cytoskeleton and affects cell-cell interaction and migration. According to recent studies, CD146 activates p38/IKK/NF- κ B pathway, up-regulates NF- κ B downstream pro-angiogenic genes, such as IL-8, intercellular adhesion molecule-1(ICAM-1), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), and VEGF, suggesting that CD146/NF-κB signaling cascade plays an indispensable role in tip selection (So et al. 2010).

Another molecule involved in tip selection is serum response factor (SRF), one kind of transcription factors. It interacts with other transcription factors, such as EST and GATA families. SRF relates to RhoA signal, regulating transcription of β- actin coordinately (De Smet et al. 2009). SRF expression is restricted to ECs in small vessel, more precisely, in tip cells and stalk cells. Endothelial SRF-deficient embryos succumb because of reduced vessel branching, which is not caused by the loss of tip cells or abnormal expression of Dll4 or Notch, but due to the thinner and fewer filopodia in tip cells, less, with disorganized actin on filopodia base. It occurs in stalk cells as well. In vitro, function loss of SRF leads to F-actin reduction, abnormal tip selection and tube structure (De Smet et al. 2009).

Cyclooxygenase (COX) is a key enzyme for prostaglandin production. COX2 subtype is induced by intracellular signals, such as growth factors. In a variety of tumors, COX2 expression is up-regulated (Toomey et al. 2009). In ECs, exogenous VEGF combines with VEGFR2, stimulates EC proliferation and tube formation by up-regulation of COX2 and prostacyclin 2(PGI2). In addition, COX2 also increases by responding to integrin αvβ3. Similarly, VEGF increases PGI2 through VEGFR1-VEGFR2 hetero dimer, and up-regulates COX2 via the PLC γ-IP3/Ca2+- calcineurin -NFAT pathway (Toomey et al. 2009). On the other hand, COX2 inhibitor blocks Akt phosphorylation in tumor ECs and induces cell apoptosis (Gately and Li 2004).

CAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) is signaling hub during angiogenesis, which regulates tip/stalk cell behavior by restraining tip cells formation. In zebrafish, the ability of PKA to regulate the tip cells is not related to notch signaling (Nedvetsky et al. 2016).

Perspective

Blood vessels provide nutrients and oxygen for tumor, as well as routes for tumor metastasis and opportunity to grow in other parts of human body. Thus, the vascular system in tumor has become a key for anti-tumor therapy. Currently targeted anti-VEGF angiogenesis therapy causes various side effects and drug resistance (Bergers and Hanahan 2008); therefore scientists are looking for novel alternative methods (Chen and Cleck 2009). Tip-stalk cells are different from the quiescent ECs, so the understanding of tip selection and tip-stalk shuffling should facilitate the design of more effective multi-targeted treatments.

There are multiple problems to consider. First, the basic knowledge about tip selection is mainly from in vitro cell culture model. But the three-dimensional environment in vivo is more complex, especially how various factors affect each other during the tip selection and tip-stalk shuffling in vivo. Second, the endothelial cell heterogeneity which could be detected by single-cell transcriptomics influences tip selection. In addition, the influence of the neuroendocrine system, immune system and microenvironment are all involved in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis is a complex process regulated by multiple factors. Modern life science believes that biological function is not usually produced by a single gene or its product, but by multiple genes, their products, the interaction among them, and their interaction with the external environment. Therefore, biomolecule network is the foundation of complex biological systems. Understanding the biomolecule network is expected to accelerate the drug targets discovery and obtain a more desirable effect on angiogenesis. Many factors have been tested in vitro to evaluate the pro-angiogenic or anti-angiogenic potential, but how they can affect tip selection and tip-stalk shuffling needs further investigation and can be promising, potential therapeutic targets for angiogenesis-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31201052, 81802815). We thank Man Lu and Huiyu Li for polishing the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Wenqi Chen, Peng Xia, Heping Wang, Jihao Tu and Xinyue Liang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xiaoling Zhang, Email: zhangxl714@sina.com.

Lisha Li, Email: lilisha@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- Adada MM, et al. Intracellular sphingosine kinase 2-derived sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates epidermal growth factor-induced ezrin-radixin-moesin phosphorylation and cancer cell invasion. FASEB J. 2015;29(11):4654–4669. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-274340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam MG, et al. Synaptojanin-2 binding protein stabilizes the notch ligands DLL1 and DLL4 and inhibits sprouting angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2013;113(11):1206–1218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(6):464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile JR, Gavard J, Gutkind JS. Plexin-B1 utilizes RhoA and rho kinase to promote the integrin-dependent activation of Akt and ERK and endothelial cell motility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):34888–34895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belair DG, et al. Human iPSC-derived endothelial cell sprouting assay in synthetic hydrogel arrays. Acta Biomater. 2016;39:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedito R, et al. Notch-dependent VEGFR3 upregulation allows angiogenesis without VEGF-VEGFR2 signalling. Nature. 2012;484(7392):110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature10908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benn A, et al. Role of bone morphogenetic proteins in sprouting angiogenesis: differential BMP receptor-dependent signaling pathways balance stalk vs. tip cell competence. FASEB J. 2017;31(11):4720–4733. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700193RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K, Gerhardt H, Bates PA. Agent-based simulation of notch-mediated tip cell selection in angiogenic sprout initialisation. J Theor Biol. 2008;250(1):25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley K, et al. The role of differential VE-cadherin dynamics in cell rearrangement during angiogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(4):309–321. doi: 10.1038/ncb2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(8):592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boareto M, et al. Jagged mediates differences in normal and tumor angiogenesis by affecting tip-stalk fate decision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(29):E3836–E3844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511814112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes RP, et al. The cytosolic NADPH oxidase subunit NoxO1 promotes an endothelial stalk cell phenotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(8):1558–1565. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler GS, et al. Degradomic and yeast 2-hybrid inactive catalytic domain substrate trapping identifies new membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MMP14) substrates: CCN3 (Nov) and CCN5 (WISP2) Matrix Biol. 2017;59:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantelmo AR, Brajic A, Carmeliet P. Endothelial metabolism driving angiogenesis: emerging concepts and principles. Cancer J. 2015;21(4):244–249. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier A, et al. MOSAIC: a multiscale model of osteogenesis and sprouting angiogenesis with lateral inhibition of endothelial cells. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(10):e1002724. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. nature. 2000;407(6801):249. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, et al. Branching morphogenesis and antiangiogenesis candidates: tip cells lead the way. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(6):315–326. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carra S, et al. Zebrafish Tmem230a cooperates with the Delta/notch signaling pathway to modulate endothelial cell number in angiogenic vessels. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(2):1455–1467. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-C, Lau LF. Functions and mechanisms of action of CCN matricellular proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(4):771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HX, Cleck JN. Adverse effects of anticancer agents that target the VEGF pathway. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(8):465–477. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintala H, et al. The matricellular protein CCN1 controls retinal angiogenesis by targeting VEGF, Src homology 2 domain phosphatase-1 and notch signaling. Development. 2015;142(13):2364–2374. doi: 10.1242/dev.121913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang J-Y, et al. WISP-1, a novel angiogenic regulator of the CCN family, promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma angiogenesis through VEGF-A expression. Oncotarget. 2015;6(6):4239–4252. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa G, et al. Asymmetric division coordinates collective cell migration in angiogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(12):1292–1301. doi: 10.1038/ncb3443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang LTH, et al. Hyperactive FOXO1 results in lack of tip stalk identity and deficient microvascular regeneration during kidney injury. Biomaterials. 2017;141:314–329. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bock K, et al. Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell. 2013;154(3):651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet F, et al. Mechanisms of vessel branching: filopodia on endothelial tip cells lead the way. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(5):639–649. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.185165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado VM, et al. Modulation of endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis: a novel function for the "tandem-repeat" lectin galectin-8. FASEB J. 2011;25(1):242–254. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-144907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Akt takes center stage in angiogenesis signaling. Circ Res. 2000;86(1):4–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G, et al. Control of vessel sprouting by genetic and metabolic determinants. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24(12):589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eelen G, et al. Endothelial cell metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(1):3–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrach S, et al. Laminin-binding integrins induce Dll4 expression and notch signaling in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2011;109(2):172–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantin A, et al. NRP1 acts cell autonomously in endothelium to promote tip cell function during sprouting angiogenesis. Blood. 2013;121:2352–2362. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-424713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(6 Suppl 16):10–14. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RS et al (2018) Filopodia and focal adhesions: an integrated system driving branching morphogenesis in neuronal pathfinding and angiogenesis. Dev Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fish JE, et al. Dynamic regulation of VEGF-inducible genes by an ERK/ERG/p300 transcriptional network. Development. 2017;144(13):2428–2444. doi: 10.1242/dev.146050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi J-i, Makagiansar IT, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan promotes endothelial cell motility and angiogenesis via engagement of galectin-3 and α3β1 integrin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(8):3580–3590. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gately S, Li WW. Multiple roles of COX-2 in tumor angiogenesis: a target for antiangiogenic therapy. Semin Oncol. 2004;31(2 Suppl 7):2–11. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt H, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(6):1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geudens I, Gerhardt H. Coordinating cell behaviour during blood vessel formation. Development. 2011;138(21):4569–4583. doi: 10.1242/dev.062323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez F, et al. Robo 4 counteracts angiogenesis in herpetic stromal keratitis. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0141925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström M, Phng L-K, Gerhardt H. VEGF and notch signaling. Cell Adhes Migr. 2007;1(3):133–136. doi: 10.4161/cam.1.3.4978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrot P et al (2018) CCN proteins as potential actionable targets in scleroderma. Exp Dermatol [DOI] [PubMed]

- Herbert SP, Stainier DYR. Molecular control of endothelial cell behaviour during blood vessel morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:551–564. doi: 10.1038/nrm3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, et al. Role of glutamine and interlinked asparagine metabolism in vessel formation. EMBO J. 2017;36(16):2334–2352. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson L, et al. Endothelial cells dynamically compete for the tip cell position during angiogenic sprouting. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(10):943–953. doi: 10.1038/ncb2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JI, Lau LF. Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(12):945–963. doi: 10.1038/nrd3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangsamaksin T, Tattersall IW, Kitajewski J. Notch functions in developmental and tumour angiogenesis by diverse mechanisms. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(6):1563–1568. doi: 10.1042/BST20140233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kangsamaksin T et al (2015) NOTCH decoys that selectively block DLL/NOTCH or JAG/NOTCH disrupt angiogenesis by unique mechanisms to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Discov 5(2):182–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, et al. Glutamine fuels proliferation but not migration of endothelial cells. EMBO J. 2017;36(16):2321–2333. doi: 10.15252/embj.201796436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Stolarska MA, Othmer HG. The role of the microenvironment in tumor growth and invasion. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;106(2):353–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura T, et al. Regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB substrate Girdin. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(3):329–337. doi: 10.1038/ncb1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch AW, et al. Robo4 maintains vessel integrity and inhibits angiogenesis by interacting with UNC5B. Dev Cell. 2011;20(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch S, et al. NRP1 presented in trans to the endothelium arrests VEGFR2 endocytosis, preventing angiogenic signaling and tumor initiation. Dev Cell. 2014;28(6):633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler NM, et al. Notch signaling in developmental and tumor angiogenesis. Genes Cancer. 2011;2(12):1106–1116. doi: 10.1177/1947601911423030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota S, Takigawa M. CCN family proteins and angiogenesis: from embryo to adulthood. Angiogenesis. 2007;10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, et al. Interleukin-8 induces the endothelial cell migration through the activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Rac1/RhoA pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7(6):782–791. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F, Huot J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100(6):782–794. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259593.07661.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RE, et al. The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Islet2a promotes angioblast migration. Dev Biol. 2016;414(2):181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrand C, et al. Critical role of Ena/VASP proteins for Filopodia formation in neurons and in function downstream of Netrin-1. Neuron. 2004;42(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, et al. Neuropilin-1 is associated with clinicopathology of gastric cancer and contributes to cell proliferation and migration as multifunctional co-receptors. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0291-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CF et al (2016) WISP-1 promotes VEGF-C-dependent lymphangiogenesis by inhibiting miR-300 in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. in Oncotarget [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin C-Y, et al. WISP-3 inhibition of miR-452 promotes VEGF-A expression in chondrosarcoma cells and induces endothelial progenitor cells angiogenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(24):39571–39581. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahabeleshwar GH, et al. Mechanisms of integrin–vascular endothelial growth factor receptor cross-activation in angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;101(6):570–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.155655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder S, et al. G-protein-coupled Receptor-2-interacting Protein-1 controls stalk cell fate by Inhibiting Delta-like 4-Notch1 signaling. Cell Rep. 2016;17(10):2532–2541. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moya IM, et al. Stalk cell phenotype depends on integration of notch and SMAD1/5 signaling cascades. Dev Cell. 2012;22(3):501–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa-Masuda A, Terai K. ERK activation in endothelial cells is a novel marker during neovasculogenesis. Genes Cells. 2016;21(11):1164–1175. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nedvetsky PI, et al. cAMP-dependent protein kinase a (PKA) regulates angiogenesis by modulating tip cell behavior in a notch-independent manner. Development. 2016;143(19):3582–3590. doi: 10.1242/dev.134767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YS, et al. CCN1 secreted by tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells promotes endothelial cell angiogenesis via integrin αvβ3 and AMPK. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(1):140–149. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peghaire C, et al. Fzd7 (Frizzled-7) expressed by endothelial cells controls blood vessel formation through Wnt/beta-catenin canonical signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(12):2369–2380. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.307926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitulescu ME, et al. Dll4 and notch signalling couples sprouting angiogenesis and artery formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(8):915–927. doi: 10.1038/ncb3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggio P, et al. Osteopontin controls endothelial cell migration in vitro and in excised human valvular tissue from patients with calcific aortic stenosis and controls. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(8):2139–2149. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146(6):873–887. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokopiou SA et al (2016) Integrative modeling of sprout formation in angiogenesis: coupling the VEGFA-Notch signaling in a dynamic stalk-tip cell selection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.02167

- Rao G, Du L, Chen Q. Osteopontin, a possible modulator of cancer stem cells and their malignant niche. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(5):e24169. doi: 10.4161/onci.24169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravelli C, et al. beta3 integrin promotes long-lasting activation and polarization of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 by immobilized ligand. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(10):2161–2171. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley AJ, et al. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302(5651):1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sainson RC, et al. TNF primes endothelial cells for angiogenic sprouting by inducing a tip cell phenotype. Blood. 2008;111(10):4997–5007. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-108597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober JM, et al. Identification of integrin alpha(M)beta(2) as an adhesion receptor on peripheral blood monocytes for Cyr61 (CCN1) and connective tissue growth factor (CCN2): immediate-early gene products expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2002;99(12):4457–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoors S, et al. Fatty acid carbon is essential for dNTP synthesis in endothelial cells. Nature. 2015;520(7546):192–197. doi: 10.1038/nature14362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra M, et al. Semaphorin 6A regulates angiogenesis by modulating VEGF signaling. Blood. 2012;120(19):4104–4115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-410076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon H, et al. Active involvement of Robo1 and Robo4 in filopodia formation and endothelial cell motility mediated via WASP and other actin nucleation-promoting factors. FASEB J. 2009;23(2):513–522. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-098269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng S, Qiao M, Pardee AB. Metastasis and AKT activation. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(3):451–454. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin M, et al. Vegfa signals through ERK to promote angiogenesis, but not artery differentiation. Development. 2016;143(20):3796–3805. doi: 10.1242/dev.137919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjoqvist M, Andersson ER (2017) Do as I say, Not(ch) as I do: lateral control of cell fate. Dev Biol [DOI] [PubMed]

- So JH, et al. Gicerin/Cd146 is involved in zebrafish cardiovascular development and tumor angiogenesis. Genes Cells. 2010;15(11):1099–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamagnone L. Emerging role of semaphorins as major regulatory signals and potential therapeutic targets in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T, et al. Blocking VEGFR-3 suppresses angiogenic sprouting and vascular network formation. Nature. 2008;454:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature07083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammela T, et al. VEGFR-3 controls tip to stalk conversion at vessel fusion sites by reinforcing notch signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(10):1202–1213. doi: 10.1038/ncb2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey DP, Murphy JF, Conlon KC. COX-2, VEGF and tumour angiogenesis. Surgeon. 2009;7(3):174–180. doi: 10.1016/s1479-666x(09)80042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H-C et al (2017) WISP-1 positively regulates angiogenesis by controlling VEGF-A expression in human osteosarcoma. Cell Death &Amp; Disease, 8: p. e2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman L, Regan ER, Bentley K. Time to decide? Dynamical analysis predicts partial tip/stalk patterning states Arise during angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weavers H, Skaer H. Tip cells: master regulators of tubulogenesis? Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;31(100):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein N, et al. A network model to explore the effect of the micro-environment on endothelial cell behavior during angiogenesis. Front Physiol. 2017;8:960. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat Med. 2011;17(11):1359–1370. doi: 10.1038/nm.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worzfeld T, Offermanns S. Semaphorins and plexins as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(8):603–621. doi: 10.1038/nrd4337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, et al. Arteries are formed by vein-derived endothelial tip cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5758. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, et al. Plexin-B1 activates NF-kappaB and IL-8 to promote a pro-angiogenic response in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Yokota Y et al (2015) Endothelial ca 2+ oscillations reflect VEGFR signaling-regulated angiogenic capacity in vivo. Elife 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa M, et al. Robo4 is an effective tumor endothelial marker for antibody-drug conjugates based on the rapid isolation of the anti-Robo4 cell-internalizing antibody. Blood. 2013;121(14):2804–2813. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-12-468363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkada G, et al. VEGFR3 does not sustain retinal angiogenesis without VEGFR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(3):761–766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423278112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecchin A, et al. How endothelial cells adapt their metabolism to form vessels in tumors. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1750. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, et al. The Matricellular protein Cyr61 is a key mediator of platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(13):8232–8242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.623074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Wu G, Dai H. The matricellular protein CCN1 regulates TNF-α induced vascular endothelial cell apoptosis. Cell Biol Int. 2016;40(1):1–6. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Groopman JE, Wang JF. Extracellular matrix regulates endothelial functions through interaction of VEGFR-3 and integrin α5β1. J Cell Physiol. 2004;202(1):205–214. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63(8):610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]