Abstract

Parents can significantly impact their adolescent child’s sexual and relationship decision-making, yet many parents are not effectively communicating with their teens about these topics. Media are sexual socialization agents for adolescents, which can encourage early or risky sexual activity. Media Aware Parent is a web-based program for parents of adolescents that was designed to improve adolescent sexual health by providing parents with the skills to have high-quality communication with their child about sex and relationships as well as to mediate their media usage. This web-based randomized controlled trial was conducted in 2018-2019 with parent-child pairs (grades 7, 8, or 9; n=355) from across the United States. Parent participants identified as mostly female (75%), white/Caucasian (74%); and non-Hispanic (92%). The youth sample was more balanced in terms of gender (45% female) and more diverse with respect to race (66% white) and ethnicity (86% non-Hispanic). Twenty-eight percent of the families identified as a single parent household, and 35% of the youth were eligible for free school lunch. The present study assessed the short-term effects of Media Aware Parent on parent-adolescent communication, adolescent sexual health outcomes, and media-related outcomes across a one-month timeframe. Parents were randomly assigned to the intervention (Media Aware Parent) or active control group (online access to medically-accurate information on adolescent sexual health). The intervention improved parent-adolescent communication quality as rated by both parents and youth. Youth were more likely to understand that their parent did not want them to have sex at this early age. Youth reported more agency over hook-ups, more positive attitudes about sexual health communication and contraception/protection, and more self-efficacy to use contraception/protection, if they decide to have sexual activity. The intervention improved media literacy skills in both parents and youth, and resulted in youth being more aware of family media rules. Parents gave overwhelming positive feedback about Media Aware Parent. The results from this pretest-posttest study provide evidence that Media Aware Parent is an effective web-based program for parents seeking to enhance parental parent-adolescent communication and media mediation, and positively impact their adolescents’ sexual health outcomes.

Keywords: Adolescent Sexual Health, Parent-Adolescent Communication, Media Literacy Education, Prevention, Program Evaluation

Introduction

There is substantial evidence of the benefits for adolescents to delay sexual intercourse, use contraception if sexually active, and have sexual experiences that are wanted and consensual. Parents can positively impact their adolescent child’s sexual outcomes through high-quality parent-adolescent communication and active and restrictive media mediation, but many parents lack the skills to do so effectively. Few, if any, evidence-based programs exist for parents to help them build these skills and, ultimately, positively affect adolescent sexual health outcomes. Therefore, a randomized control trial was conducted to evaluate the short-term impact of a web-based program for parents designed to enhance parent-adolescent communication about sex and relationships and parental media mediation on parent-adolescent communication, adolescent sexual health outcomes, and media-related outcomes across a one-month timeframe.

Adolescent Sexual Health

Many adolescents are engaging in sexual behaviors that put them at risk for negative health outcomes including contracting sexually transmitted infections and experiencing unplanned pregnancy. Approximately 4 in 10 high school students have had sexual intercourse, and nearly half (46%) of sexually active high school students did not use a condom at last intercourse (Kann et al., 2018). The United States has one of the highest teen pregnancy rates among industrialized countries (Sedgh, Finer, Bankole, Eilers, & Singh, 2015), and half of the 20 million new sexually transmitted infections reported each year are among people ages 15-24 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). In addition, while sex is a normal part of development (Tolman & McClelland, 2011), early sexual debut, usually defined as before the ages of 14-16, is associated with sexual risk-taking behaviors and negative health outcomes, including engaging in unprotected sex (Martinez, Copen, & Abma, 2011), having multiple sexual partners, using substances before sex, experiencing a teen pregnancy (Kaplan, Jones, Olson, & Yunzal-Butler, 2013), and sexually transmitted infections among females (Kugler, Vasilenko, Butera, & Coffman, 2017). These statistics highlight the need for early evidence-based sexual health promotion efforts aimed at empowering youth to make healthy sexual decisions.

The Role of Parents

Parents are a significant influence on adolescents’ sexual beliefs and behaviors. Parent-adolescent communication about sexual health has been shown to promote healthier behaviors in youth including abstinence (Cederbaum, Rodriguez, Sullivan, & Gray, 2017), fewer sexual partners (Aspy et al., 2006; Crosby, Hanson, & Rager, 2009), contraceptive use (Widman, Choukas-Bradley, Noar, Nesi, & Garrett, 2016), and partner communication about sexually transmitted infections (Crosby et al., 2009). Research has shown that the timing, content, and context of parent-adolescent communication about sexual health are important. Researchers have argued that parent-adolescent communication about sex ideally should occur before first sexual intercourse (Beckett et al., 2010) and on an ongoing basis (Martino, Elliott, Corona, Kanouse, & Schuster, 2008). Communication quality and style impact the efficacy of parent-adolescent sexual health communication, with research indicating open, honest, informal, comfortable, and knowledgeable conversations to be most effective (Flores & Barroso, 2017).

Despite the positive impacts of parent-adolescent communication about sex and the fact that teens see their parents as important sources of sexual health information (Pariera & Brody, 2018), parents can be reluctant to initiate these conversations (Flores & Barroso, 2017). Almost one-quarter of adolescent females and one-third of males report that they have not had any conversations with their parents about sexual topics, such as saying no to sex (Lindberg, Maddow-Zimet, & Boonstra, 2016). Parents are more likely to discuss sexual health in general terms (Flores & Barroso, 2017), and both mothers (Farringdon, Holgate, McIntyre, & Bulsara, 2013) and fathers (Guilamo-Ramos et al., 2019) report lacking accurate medical information. Thus, many parents could benefit from sexual health knowledge and communication strategies (Pariera, 2016).

The Role of Media

Adolescents are exposed to a myriad of unhealthy sexual media messages. Media use is pervasive among teens with almost half of teens online almost constantly (Anderson & Jiang, 2018) and spending more than four hours a day on screens (Rideout, 2015). Content analyses have consistently shown that is it commonplace for popular entertainment media to contain sexual content, including television shows, movies, music lyrics, music videos, and video games (Ward, Erickson, Lippman, & Giaccardi, 2016). For example, over 80% of films and television programs contain sexual content and representations of women in video games are frequently hyper-sexualized. Sexually active teens are overrepresented in media messages aimed specifically at young adolescents, ages 12-15 (Signorielli & Bievenour, 2015). In addition, the majority of adolescents have seen sexually explicit media messages, especially on the internet (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009). Of concern, sexual media messages often exclude information related to sexual risk and responsibility (Gottfried, Vaala, Bleakley, Hennessy, & Jordan, 2013) or mentions of condoms or contraception (Dillman Carpentier, Stevens, Wu, & Seely, 2017). In summary, as part of their daily lives and across media platforms, adolescents are exposed to a plethora of sexual media messages many of which communicate unhealthy and hypersexual depictions of relationships and sexuality.

Exposure to sexual media can influence adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviors (Coyne et al., 2019). Specifically, a variety of empirical studies have found that exposure to sexual media is associated with more permissive attitudes about uncommitted sexual behavior, expectations about sex, and perceptions of peer sexual behavior; further, a causal relationship has been found between sexual media exposure and both sexual activity and teen pregnancy (Ward, 2016). Several theoretical frameworks, including cultivation theory, social learning theory, the 3AM model, and the message interpretation process model, have been used to explain the impact of sexual media exposure on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors (Scull & Malik, 2019), and researchers have suggested that media acts as a “super peer’ that can encourage adolescents to engage in early and risky sexual behaviors (Brown, Halpern, & L’Engle, 2005).

Research suggests that critical thinking about media messages may serve as a protective factor against the potentially harmful impact of media on adolescent sexual health outcomes. For example, adolescents’ perceived realism of media messages has been found to moderate the relationship between media exposure and permissive attitudes toward sex (Baams et al., 2015). Therefore, it is important for youth to learn how to critically analyze and evaluate media messages. Evaluations of media literacy education programs for adolescents with both abstinence (Pinkleton, Austin, Chen, & Cohen, 2012) and comprehensive (Scull, Kupersmidt, Malik, & Morgan-Lopez, 2018) sexual health education approaches have found promising effects for youth sexual health outcomes.

Parents can help their children leam these skills through active media mediation, which includes parents discussing the content of media with their child. Both active parental media mediation and restrictive mediation, which includes parental rules about youth media use, have been found to predict adolescent sexual outcomes (Collier et al., 2016). Therefore, parents should address media when talking with their children about sex, as well as set rules about media use. Parental media mediation can serve as a protective factor against the potential negative effects of media on youth, yet many parents do not have the knowledge or skills necessary to engage in these types of mediation with their children.

The Intervention

A number of evidence-based programs exist for parents with the aim of promoting adolescent sexual health (Wight & Fullerton, 2013); however, none appear specifically designed to help parents address media influence. Additionally, most programs for parents are face-to-face (Akers, Holland, & Bost, 2011), which can be a significant barrier for parent participation. Therefore, Media Aware Parent was developed to fill these gaps.

Media Aware Parent is an interactive web-based program for parents designed to provide skills and resources to effectively communicate with their adolescent children about sexual and relationship health and media. It provides parents with medically-accurate, comprehensive information about adolescent sexual and relationships health topics, practice in critical analysis of media messages, media mediation strategies, tips for engaging in high-quality parent-adolescent communication about sex and relationships, opportunities for skills practice, and the ability to create a family media plan. The main section of the self-paced and self-directed program consists of an introduction/tutorial and five interactive modules: 1) Teen Influences; 2) Media Makers; 3) Healthy Relationships; 4) Sexual Health; and, 5) Continuing the Conversation. Each of the five modules consists of a short introduction video, two highly interactive content-based lessons for parents (e.g., clickable activities, open-ended text box questions, branching activities), and a PDF of instructions for activities that parents can complete with their child outside of the program (e.g., instructions on how to use songs that are playing on the radio as a way to start a conversation with their child about healthy and unhealthy romantic relationships). The program covers a wide range of adolescent sexual and relationship health topics including influences on teen sexual decision-making, gender stereotypes, social media and internet safety, teen dating, consent, abstaining from sexual activity, sexually transmitted infections, and contraception/protection. Throughout the program parents are provided with tips and skills focused on enhancing parent-adolescent communication about sex and relationships. A variety of media examples relevant to teens are referenced in the program including popular music, social media posts, and clips from television shows. Parents learn effective ways to discuss media messages with adolescents in order to enhance their media literacy skills and counter unhealthy media messages that promote risky sexual behaviors. Parents also have the opportunity to create a customized family media plan that details family rules about media use.

While Media Aware Parent is designed for parents to complete (i.e., not with their child), there are designated information pages and activities that, if the parent chooses, they can share with their child by clicking a button on the page which automatically posts the content to a teen section of the program. Throughout the program there are sixteen opportunities for parents to choose to share content with their child. In addition to the main sections of the program, Media Aware Parent also includes additional components for parents that can be accessed from the program main page. Specifically, there is a Spotlights section that contains twelve short videos of adolescents talking about various sexual health related topics (e.g., teen dating), and a Resources section that contains sub-sections on eleven different topics (e.g., pregnancy prevention) where parents are provided with links to additional trusted resources on each topic (i.e., U.S. Food and Drug Administration Birth Control Guide). Media Aware Parent is self-paced, parents can access the lessons and other program components in any order, and parents can return to content as often as they choose.

Program development was guided by established theoretical frameworks widely shown to predict adolescent sexual health and behaviors, specifically, the theory of reasoned action and its extension, the theory of planned behavior (TRA/TPB) (Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1975), and the message interpretation process (MIP) model (Austin, 2007). The iterative process of program development was informed by experts in adolescent development and sexual health, media literacy education, and instructional design, as well as input from focus groups with parents and youth, usability testing, and an initial feasibility study.

Study Aims

This study utilized an intent-to-treat, pretest/posttest, randomized controlled trial design with an active control group to evaluate the short-term efficacy of Media Aware Parent for impacting youth outcomes related to sexual health, specifically adolescent self-reports of variables that are stable predictors of adolescent sexual activity and contraceptive use as well as media message processing variables. It is hypothesized that youth predictors of sexual behavior and predictors of safe sexual behavior will be positively impacted in the intervention group. Additionally, it is hypothesized that Media Aware Parent will have positive effects on parent cognitions related to sexual health communication, parent sexual health communication behaviors, and overall parent-adolescent communication quality compared to the active control group. Finally, it is hypothesized that parent media-related behaviors, youth media-related behaviors, as well as parent and youth media-related cognitions will improve for the intervention group.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 355 parent-child pairs between the intervention (n=172) and control groups (n=183). See Table 1 for sample characteristics. The majority of participants identified as mothers/female guardians. Youth participants were more evenly distributed by gender. Both the parent and youth samples were mostly white and non-Hispanic/Latino. The majority of parent participants reported completing some college or a 2-year degree, being heterosexual, being married, and that their children do not qualify for free lunch at school. Chi-square analyses revealed that these sample characteristics did not differ between the intervention and control groups. Parent participants were, on average, 40.77 years of age (SD=5.79; range 29-62) at pretest. Youth participants were, on average, 13.00 years of age (SD=0.88; range 11-16) at pretest. T-tests revealed that ages (for both parents and youth) did not differ between the intervention and control groups (p>.05).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics with results from chi-square analyses between groups

| Overall (N=355) | Intervention (n=172) | Control (n=183) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | χ | p-value | |

| Parent gender | 2.13 | .55 | |||

| Mother/female guardian | 261 (74.57%) | 126 (74.12%) | 135 (75.0%) | ||

| Father/male guardian | 85 (24.29%) | 41 (24.12%) | 44 (24.44%) | ||

| Non-binary or prefer not to disclose | 4(1.14%) | 3 (1.76%) | 1 (0.56%) | ||

| Child gender | 5.40 | .25 | |||

| Female | 157 (45.11%) | 75 (44.12%) | 82 (46.07%) | ||

| Male | 183 (52.59%) | 88 (51.76%) | 95 (53.37%) | ||

| Non-binary or prefer not to disclose | 8 (2.3%) | 7 (4.12%) | 1 (0.56%) | ||

| Parent race | 2.49 | .78 | |||

| Black/African-American | 50 (14.93%) | 29 (17.68%) | 21 (12.28%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 247 (73.73%) | 117 (71.34%) | 130 (76.02%) | ||

| Asian | 6 (1.79%) | 2 (1.22%) | 4 (2.34%) | ||

| Native American/Alaska Native | 2 (0.60%) | 1 (0.61%) | 1 (0.58%) | ||

| Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 2 (0.60%) | 1 (0.61%) | 1 (0.58%) | ||

| More than one | 28 (8.36%) | 14 (8.54%) | 14 (8.19%) | ||

| Child race | 5.36 | .37 | |||

| Black/African-American | 50 (14.49%) | 29 (17.26%) | 21 (11.86%) | ||

| White/Caucasian | 226 (65.51%) | 108 (64.29%) | 118 (66.67%) | ||

| Asian | 5 (1.45%) | 3 (1.79%) | 2 (1.13%) | ||

| Native American/Alaska Native | 2 (0.58%) | 1 (0.60%) | 1 (0.56%) | ||

| Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian | 2 (0.58%) | 2 (1.19%) | 0 (0.00%) | ||

| More than one | 60 (17.39%) | 25 (14.88%) | 35 (19.77%) | ||

| Parent Ethnicity | .01 | .94 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 27 (7.76%) | 13 (7.65%) | 14 (7.87%) | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 321 (92.24%) | 157 (92.35%) | 164 (92.13%) | ||

| Child Ethnicity | .36 | .55 | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 49 (13.92%) | 22 (12.79%) | 27 (15.00%) | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 303 (86.08%) | 150 (87.21%) | 153 (85.00%) | ||

| Parent Education | 2.63 | .62 | |||

| Some High School | 7 (2.13%) | 4 (2.52%) | 3 (1.78%) | ||

| High School Graduate/GED | 30 (9.15%) | 14 (8.81%) | 16 (9.47%) | ||

| Some College/2-Year Degree | 123 (37.50%) | 66 (41.51%) | 57 (33.73%) | ||

| 4-Year College | 90 (27.44%) | 41 (25.79%) | 49 (28.99%) | ||

| Graduate/Professional Degree | 78 (23.78%) | 34 (21.37%) | 44 (26.03%) | ||

| Parent Sexual Orientation | 1.64 | .80 | |||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 316 (93.49%) | 152 (92.68%) | 164 (94.25%) | ||

| Gay or Lesbian | 7 (2.07%) | 3 (1.83%) | 4 (2.30%) | ||

| Bisexual | 12 (3.55%) | 7 (4.27%) | 5 (2.87%) | ||

| Prefer Not To Say/Self-Describe | 3 (0.89%) | 2 (1.22%) | 1 (0.58%) | ||

| Single Parent | 3.07 | .08 | |||

| Yes | 100 (28.25%) | 56 (32.56%) | 44 (24.18%) | ||

| No | 254 (71.75%) | 116 (67.44%) | 138 (75.82%) | ||

| SES (Free Lunch) | 1.35 | .51 | |||

| Yes | 112 (34.78%) | 59 (37.11%) | 53 (32.52%) | ||

| No | 192 (59.63%) | 93 (58.49%) | 99 (60.74%) | ||

| Don’t Know | 18 (5.59%) | 7 (4.40%) | 11 (6.75%) | ||

Procedures

An Institutional Review Board approved of the methods and measures used in this study. Parents were recruited through a website and flyers that advertised this as a study where parents would be asked to evaluate online resources that could be helpful in talking about sexual health with their child. Inclusion criteria stipulated that participants be the parent or caregiver of a child in 7th, 8th, or 9th grade. Participants were also required to be proficient in English and have access to a laptop or tablet that had Wi-Fi capabilities (in order to access the study questionnaires and web-based resources). Those interested completed an online screener to determine their eligibility, and if eligible were then prompted to endorse online informed consent forms. Parents with more than one eligible child were asked to choose one child to participate in the study. Participants’ information was verified by phone. Pairs were randomized to intervention (n=179) or active control (n=186), stratified by parent gender and race/ethnicity. Participants were emailed links to the pretest questionnaires and instructed to complete their respective questionnaires separately. Parent-adolescent pairs who did not complete both pretest questionnaires were dropped from the study (n=7, intervention; n=2, control). One control group participant pair requested to be withdrawn from the study because of online data concerns. After pretest, intervention parents received online access to Media Aware Parent, and control parents received online access to professionally produced (e.g., Centers for Disease Control – United States) medically-accurate sexual health brochures (PDFs) that corresponded to health topics in Media Aware Parent. They were asked to review their resource(s) within two weeks. However, parents had access for the duration of their participation. Parents, in the intervention and control groups, received an email reminder to review the program/resources one week after receiving access and an additional reminder on the thirteenth day after receiving access. Approximately one month after pretest, participant pairs were asked to complete separate web-based posttest questionnaires. Control parents were provided with free access to Media Aware Parent after the study was completed. Participant pairs received a gift card incentive for each component of the study (i.e., $30 for pretest; $45 for resource review; and $50 for posttest).

Measures

Parent and youth participants completed separate questionnaires. Each was asked to respond to questions with the respective participating parent or child in mind. Youth and parents reported on demographic characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, and gender. Additionally, parents were asked about their education, sexual orientation, relationship status, parenting status (e.g., single parent), religiosity (Hoge, 1972), and socioeconomic status (i.e., child qualifies for free school lunch). Youth reported if they had ever had oral, vaginal, or anal sex. The questionnaires included measures of antecedents and youth sexual health and media-related outcomes. Parents were asked at posttest to rate their satisfaction with their assigned resource on a 4-pt. Likert scale. Intervention group parents were also asked to respond to statements specifically about Media Aware Parent compared with other available resources for parents. An attention check was included on each questionnaire (“Answer 3 for this question”). Several other measures were included on the parent and youth questionnaires (e.g., parental monitoring of activities) for use with other lines of research but were not hypothesized for these intervention analyses and therefore are not described in this paper.

With regard to dosage, the online learning management system that housed Media Aware Parent recorded information about participants’ use of the program, including 1) the completion of each of the main program sections; 2) program engagement - the number of times the user interacted with available functionality in each lesson (e.g., entering answers to questions; clicking buttons that reveal information); 3) whether the parent user shared each of the 16 available sections of content with their child; and, 4) whether the child completed the sections shared by the parent. In addition to information about participants’ use of the main program sections, the learning management system also tracked the number of Spotlight videos the user played; and, 5) the number of sub-sections clicked on in the Resources.

Antecedent measures.

Parent-adolescent connectedness.

Quality of parent-adolescent communication (parent).

Parents reported on their perceptions of how well they and their child communicate with each another (16 items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.85; adapted from Prado et al., 2007). Sample items include “My child tries to understand my point of view” and “When I ask questions, I get honest answers from my child.” Higher values indicate better perceived quality of communication between the parent and adolescent from the perspective of the parent.

Quality of parent-adolescent communication (youth).

Youth reported on their perceptions of how well their parent and they communicate with each another (eight items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.88; adapted from Mallett et al., 2011). Sample items include “My parent wants to understand my side of things when we talk” and “I can trust my parent when we talk.” Higher values indicate better perceived quality of communication between the parent and adolescent from the perspective of the youth.

Supportive parenting (parent).

Parents reported on how often they show support for their child (three items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Always; α=.75; adapted from Conger et al., 2011). Sample items include “How often do you let your child know you care about them?” and “How often do you listen to your child carefully?” Higher values indicate more supportive parenting.

Supportive parenting (youth).

Youth reported on how often they receive support from their parent (three items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Always; α=.83; adapted from Conger et al., 2011). Sample items include “How often does your parent let you know they care about you?” and “How often does your parent listen to you carefully?” Higher values indicated more perceived support from the parent by the youth.

Parent sexual health communication cognitions.

Importance.

Parents reported on their perceptions of the importance of sexual health communication with their child (19 items; 4-point Likert scale; Not at all important to Very important; α=.95; adapted from communication behavior measure from Schuster et al., 2008). Samples items include “How important do you think it is for you to talk to your child about… (sexting/how pregnancy happens/how to use a condom/unhealthy relationships/reasons to wait to have sex/sexual consent, etc.)” Higher values indicate greater perceived importance of sexual health communication.

Comfort.

Parents reported on their comfort in sexual health communication with their child (19 items; 5-point Likert scale; Not at all comfortable to Very comfortable; α=.97; adapted from communication behavior measure from Schuster et al., 2008). Sample items include “How comfortable do you feel talking to your child about… (sexting/how pregnancy happens/how to use a condom/unhealthy relationships/reasons to wait to have sex/sexual consent, etc.)” Higher values indicate more comfort with sexual health communication.

Self-efficacy.

Parents reported on their perceived ability to communicate sexual health information to their child (19 items; 7-point Likert scale; Not sure at all to Completely sure; α=.96; adapted from communication behavior measure from Schuster et al., 2008). Sample items include “I can always explain to my child about… (sexting/how pregnancy happens/how to use a condom/unhealthy relationships/reasons to wait to have sex/sexual consent, etc.)” Higher values indicate greater perceived efficacy with sexual health communication.

Outcome expectancies.

Parents reported on what they expected to result from sexual health communication with their child (23 items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.89; adapted from Dilorio et al., 2001). Sample items include “If I talk with my child about sex topics, I will feel like a responsible parent” and “If I talk with my child about sex topics, I will feel ashamed (reverse code).” Higher values indicate more positive expectancies of sexual health communication.

Reservations about sexual health communication.

Parents reported on their reservations regarding sexual health communication with their child (21 items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.95; adapted from Jaccard, Dittus, & Gorgon, 2000). Sample items include “It would embarrass my child to talk with me about sex and birth control” and “My child would ask me too many personal questions if I tried to talk with him/her about sex and birth control.” Higher values indicate more reservations about sexual health communication.

Perceived role in sexual education.

Parents reported on their perceived role in sexual health communication with their child (one item; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree). “I feel that someone else would do a better job teaching my child about sex and relationships.” This item was reversed-coded so that higher levels reflect stronger feelings of their perceived role in sexual health communication with their child.

Parent sexual health communication behaviors.

Frequency of sexual health discussion (parent).

Parents reported on how frequently they communicated with their child about sexual health (one item; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often). “How frequently do you talk to your child about sex and romantic relationships?” Higher values indicate more frequent sexual health communication.

Frequency of sexual health discussion (youth).

Youth reported on how frequently they communicated with their parent about sexual health (one item; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often). “How frequently does your parent talk to you about sex and romantic relationships?” Higher values indicate more frequent sexual health communication.

Parent media-related cognitions.

Perceived realism.

Parents reported on how realistic they find teen behavior in media (six items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.88; adapted from Scull, Malik, & Kupersmidt, 2014 and sex-related media myths variable from Pinkleton, Austin, Cohen, Chen, & Fitzgerald, 2008). Sample items include “Teens in media do things that average teens do” and “Teens in media are as sexually experienced as average teens.” Higher values indicate more perceived realism of media messages.

Media skepticism.

Parents reported on their judgments regarding the veracity of certain information in media messages (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; ±=.76; adapted from Scull et al., 2014). Sample items include “Media are dishonest about what might happen if people have sex” and “Media do not tell the whole truth about relationships.” Higher values indicate more belief that media messages can be misleading.

Media message completeness.

Parents reported on their perceived completeness of messages found in media (one item; 5-point Likert scale; Incomplete to Complete). They viewed an alcohol advertisement with a romantic theme and were asked “How complete is the information in this advertisement.” Higher values indicate that the respondent is more likely to believe that the message contains all necessary information for the viewer and is not thinking critically about the message.

Parent media-related behaviors.

Adolescent sexual media diet (youth).

Youth sexual media diet was calculated from two sets of responses adapted from Bleakley, Hennessy, Fishbein, & Jordan (2008). First, youth indicated how frequently they use the following media formats: watch television shows, listen to music, watch music videos, watch movies, read magazines, play video games, go on social media, visit websites, not including social media; and view pornography (4-point Likert scale; Never to Often). Next, youth rated the amount of sexual content in each of the media formats they use: “How would you rate the amount of sexual content in the television shows you watch/the music you listen to/etc.?” (4-point Likert scale: No sexual content to A lot of sexual content). It was assumed that pornography would receive a score of four for sexual content. Matched responses were multiplied (e.g., amount of TV viewing multiplied by the TV sexual content score) and summed to create a composite sexual media diet score whereby higher values indicate more sexual media exposure.

Media rules (parent).

Parents reported about the media rules in their family, “Does your family have rules about media use? (one item; Yes, No, Unsure).

Media rules (youth).

Youth reported about the media rules in their family, “Does your family have rules about media use? (one item; Yes, No, Unsure).

Evaluative media mediation (parent).

Parents reported on how often they engage in discussion of media messages with their child (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often; α=.91; adapted from Valkenburg, Kremar, Peeters, & Marseille, 1999). Sample items include “How often do you point out why some things the people in media messages do are bad?” and “How often do you explain what something in a media message really means?” Higher values indicate more frequent evaluative media mediation.

Evaluative media mediation (youth).

Youth reported on how often their parent discusses media messages with them (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often; α=.91; adapted from Valkenburg et al., 1999). Sample items include “How often does your parent point out why some things the people in media messages do are bad?” and “How often does your parent explain what something in a media message really means?” Higher values indicate more frequent evaluative media mediation.

Restrictive media mediation (parent).

Parents reported on how often they set rules for their child’s media use (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often; α=.83; adapted from Valkenburg et al., 1999). Sample items include “How often do you set specific times for your child to use media devices?” and “How often do you forbid your child to watch or listen to certain things in the media?” Higher values indicate more frequent restrictive media mediation.

Restrictive media mediation (youth).

Youth reported on how often their parents set rules for their media use (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often; adapted from Valkenburg et al., 1999). Sample items include “How often does your parent set specific times for you to use media devices?” and “How often does your parent forbid you to watch or listen to certain things in the media?” Higher values indicate more frequent restrictive media mediation.

Frequency of discussion about media and sex (parent).

Parents reported on how frequently they discuss depictions of sex and relationships in media with their child: “How frequently do you talk to your child about what they see in media about sex and relationships?” (one item; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often).

Frequency of discussion about media and sex (youth).

Youth reported on how frequently they discuss depictions of sex and relationships in media with their parent: “How frequently does your parent talk to you about what you see in media about sex and relationships?” (one item; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Often).

Outcome Measures.

Predictors of sexual behavior.

Perceived parental permissiveness.

Youth reported on their perceptions of their parent’s permissiveness regarding their sexual activity (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.76). Sample items include “My parent would approve of my having sex at this time in my life” and “My parent has specifically told me not to have sex. (reverse code)” Higher values indicate that the youth believes their parent is more permissive of their sexual activity as a teen.

Attitudes towards teen sex.

Youth reported on their own attitudes towards teenagers engaging in sexual behavior 9four items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.67; adapted from Basen-Engquist et al., 1999). Sample items include “I think it is OK for teens to be sexually active” and “Teens should wait until they are older before they have sex. (reverse code)” Higher values indicate that youth have more positive attitudes about teen sexual activity.

Normative beliefs about teen sex.

Youth rep orted on the proportion of teens they believe are engaging in sexual behavior: “What percentage of teens are having sex? [(0% (no teens) to 100% (all teens)].”

Self-efficacy to abstain from sex.

Youth reported on their perceived ability to abstain from sex (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.87; adapted from Soet, Dudley, & Dilorio, 1999). Sample items include “I could say no to someone who is pressuring me to have sex” and “I know that I can wait to be sexually active.” Higher values indicate higher levels of self-efficacy for refusing sexual activity.

Willingness to hook-up though unwanted.

Youth reported on their willingness to engage in a hook-up, despite the hook-up being unwanted: “Suppose you were with a boy/girlfriend. S/he wants to hook-up, but you are not sure that you want to. In this situation, how willing would you be to go ahead and hook-up anyway?” (4-point Likert scale; Very unwilling to Very willing; adapted from Gibbons, Gerrard, Blanton, & Russell, 1998).

Intentions to engage in sexual activity.

Youth reported on their intentions to engage in sexual activity in the future: “How likely is it that you will have any type of sexual contact with another person (oral sex, anal sex, vaginal sex, or genital-to-genital contact) in the next year?” (4-point Likert scale; Not likely at all to Very likely; adapted from L’Engle, Brown, & Kenneavy, 2006).

Predictors of safe sexual behavior.

Attitudes toward sexual communication.

Youth reported on their attitudes towards sexual communication (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.89; adapted from Soet et al., 1999). Sample items include “Before deciding to have sex, I believe teens should talk with their parents or another trusted adult” and “Before deciding to have sex, I believe teens should talk with a doctor or other medical professional.” Higher values indicate more positive attitudes toward sexual communication.

Intentions to communicate with a medical professional.

Youth reported on their intention to talk with a medical professional prior to sexual activity: “Before deciding to have sex, how likely would you be to talk to your doctor or other medical professional?” (4-point Likert scale; Not at all likely to Very likely; adapted from Scull et al., 2018).

Attitudes toward teen contraception use.

Youth reported on their attitudes towards using contraception or other forms of protection (four items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.86; adapted from Basen-Engquist et al., 1999). Sample items include “I think condoms should always be used if a teen has sex” and “I think a condom or dental dam should be used if a teen has oral sex.” Higher values indicate more positive attitudes toward teen contraceptive use.

Self-efficacy to use contraception.

Youth reported on their perceived ability to use contraception or other forms of protection (four items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.81; adapted from Soet et al., 1999). Sample items include “If I wanted to, I could get condoms or another form of contraception” and “If I decided to have sex, I could use a condom correctly or explain to my partner how to use a condom correctly.” Higher values indicate more belief in the youth’s ability to use contraception or another form of protection.

Willingness to have unprotected sex.

Youth reported on their willingness to have sex without using protection: “Suppose you were with a boyfriend/girlfriend. He/she wants to have sex, but neither of you have any form of protection. In this situation, how willing would you be to go ahead and have sex anyway?” (4-point Likert scale; Very unwilling to Very willing; adapted from Gibbons et al., 1998). Higher values indicate more willingness to have unprotected sex.

Media-related outcomes

Teen risky online behavior.

Youth reported on their behavior online (eight items; 4-point Likert scale; Never to Always; α=.77; adapted from Byrne, Katz, Lee, Linz, & McIlrath, 2014). Sample items include “How often have you looked for sexual stuff online?” and “How often has an adult stranger online wanted to meet you in real life?” Higher values indicate youth experiencing more risk online.

Perceived realism.

Youth reported on how realistic they find teen behavior in media (six items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.83; adapted from Scull et al., 2014 and from sex-related media myths variable in Pinkleton et al., 2008). Sample items include “Teens in media do things that average teens do” and “Teens in media are as sexually experienced as average teens.” Higher values indicate more perceived realism of media messages.

Media skepticism.

Youth reported on their judgments regarding the veracity of certain information in media messages (five items; 4-point Likert scale; Strongly disagree to Strongly agree; α=.73; adapted from Scull et al., 2014). Sample items include “Media are dishonest about what might happen if people have sex” and “Media do not tell the whole truth about relationships.” Higher values indicate more belief that media messages can be misleading.

Media message completeness.

Youth reported on the perceived completeness of messages found in media. They viewed an alcohol advertisement with a romantic theme and were asked “How complete is the information in this advertisement” (5-point Likert scale; Incomplete to Complete). Higher values indicate that the respondent is more likely to believe that the message contains all necessary information for the viewer and is not thinking critically about the message.

Statistical Analysis

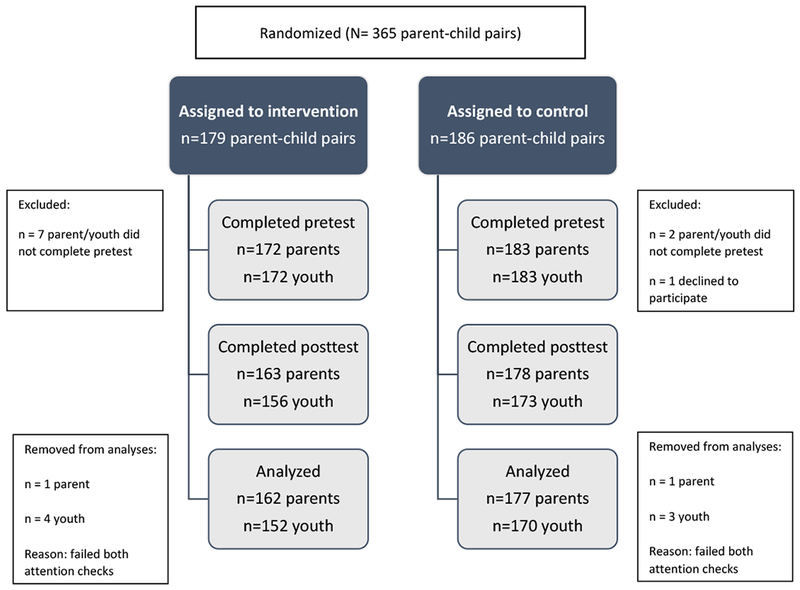

A priori power analyses conducted with Optimal Design (Raudenbush et al., 2011) indicated that with desired power of .80, an expected effect size of d=.30, α=.05, and a correlation of r=.5 between measurement occasions, the desired sample was N=328. Participants were excluded from the analyses if they failed both attention checks, either by not answering the question or choosing the incorrect response (see Figure 1). There were no arbitrary coding decisions or dichotomizing of variables to describe. Two outcome variables were eliminated from the analyses due to poor reliability (both parent and youth report of 19 communication topics discussed between the parent and youth). Furthermore, two outcome variables were eliminated from the analyses for parsimony. Both were similar to another outcome and the one that was more proximal to adolescent sexual health was retained in the analyses. These include youth intentions to have sex before graduating high school (youth intentions to have sex in the next year was retained) and youth perceived parent permissiveness of teen sex (youth perceived parent permissiveness of their own sexual activity was retained). Two measures of the quality of parent-adolescent communication were included on the questionnaires for both parent and youth; however, only one measure for each respondent was analyzed due to the other measure having poor reliability.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the intervention group’s use of the program and for the antecedent and youth outcome variables. Main analyses were conducted using R v.3.5.2 (R Core Team, 2018). To examine intervention effects, a residual difference score approach was used to provide an estimate of change from baseline (Little, 2013) and is assessed by regressing post-intervention scores onto baseline scores and the treatment variables. Binary outcomes were assessed with logistic regression. All analyses used standard errors which were robust to non-normality and heteroskedasticity and included gender, age, race, and ethnicity (for both parents and youth); youth’s rating of parental relationship quality; and parent’s religiosity as covariates.

Missing data were handled using listwise deletion, also known as complete case analysis. Listwise deletion provides unbiased estimate of model parameters when missing data are missing completely at random (MCAR), though it has lower power to detect effects than missing data techniques such as multiple imputation. We choose listwise deletion as a missing data technique to allow us to use robust standard errors in all analyses. Missing data due to dropout was unrelated to intervention condition, demographic variables, and pre-test scores on outcome variables. Non-dropout missing data was relatively rare, less than 5% of total responses. Using multiple imputation to handle missing data did not change the pattern of results reported below.

Results

Dosage Analyses

Descriptive statistics on the intervention group’s dosage of Media Aware Parent were conducted (see Table 2). On average, 79% of the program main sections was completed by parents. Within this content, parents clicked on an average of about 73% of the available interactivities, suggesting that most parents did not just click through the program without engaging in it. Parents, on average, shared with their teens about 44% of the available content for teens (e.g., video of how pregnancy happens). Of the content shared by parents, teens completed, on average, 45%. Parents also interacted with the program outside the main content, including playing about 59% of the Spotlight videos of teens (e.g., teens discuss what they know about contraception/protection) and opening the list of links to about 60% of the available topics (e.g., more information on online privacy). Overall, it is estimated that parents completed on average 69% of the available content, including bonus content. Twelve parents did not interact with the program at all.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the intervention group program dosage

| M | SD | % | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main sections | 16.65 | 6.37 | 79.29% | 0 | 21 |

| Interactivities clicked | 102.47 | 47.53 | 73.19% | 0 | 140 |

| Content shared with child | 7.01 | 5.71 | 43.81% | 0 | 16 |

| Content completed by child | 3.34 | 5.20 | 45.00% | 0 | 16 |

| Resources | 6.60 | 5.26 | 60.00% | 0 | 11 |

| Spotlight videos | 7.11 | 5.84 | 59.25% | 0 | 12 |

| Whole program | 30.36 | 15.79 | 69.00% | 0 | 44 |

Note: percentage completed by child is calculated based on the total content shared with them and not the total available content.

Descriptive Statistics

Interscale correlations were examined for the antecedent variables (see Table 3) and outcome variables (see Table 4). All significant relationships between antecedent variables were as expected except for a small positive association between parents’ perceived realism of media messages and parents’ report of supportive parenting (.11, p<.05). Correlations for antecedent variables ranged from a minimum of 0.00 between parents’ perceived realism of media messages and parents’ reported quality of parent-adolescent communication and a maximum of −0.71 between parents’ reservations about sexual health communication and parents’ positive outcome expectancies of sexual health communication. All significant relationships between outcome variables were as expected except for a few, small positive associations, namely youths’ media skepticism and youths’ risky online behavior (.15, p<.05) and youths’ media skepticism and youths’ normative beliefs about teen sex (.14, p<.05). Correlations for outcome variables ranged from a minimum of 0.00 between perceived youths’ perceived realism of media messages and youths’ perceived parental permissiveness and a maximum of 0.54 between youths’ willingness to have unprotected sex and youths’ willingness to hook-up though unwanted. Overall, the pattern of interscale correlations for both the antecedent and outcome variables suggested that multicollinearity would not be a problem for the analyses. Finally, means, standard deviations, and ranges were calculated for the antecedent and outcome variables (see Table 5).

Table 3.

Correlation table for antecedent variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quality of P-A communication (Y) | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Quality of P-A communication (P) | .35*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Supportive parenting (Y) | .56*** | .31*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Supportive parenting (P) | .17* | .46*** | .27*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Importance of sexual health comm (P) | .10 | .19** | .05 | .13* | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Comfort of sexual health comm (P) | .18** | .44*** | .10 | .29*** | .23*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Self-efficacy for sexual health comm (P) | .16* | .44*** | .12* | .35*** | .35*** | .69*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 8 | Expectancies for sexual health comm (P) | .27*** | .59*** | .26*** | .33*** | .33*** | .57*** | .56*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | Reservations about sexual health comm (P) | −.26*** | −.59*** | −.21** | −.33*** | −.31*** | −.54*** | −.47*** | −.71*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 10 | Perceived role in sexual education (P) | .20** | .44*** | .10 | .25*** | .15* | .41*** | .38*** | .51*** | −.56*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 11 | Frequency of sexual health comm (Y) | .23*** | .16* | .28*** | .09 | .04 | .17* | .20** | .29*** | −.25*** | .12* | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 12 | Frequency of sexual health comm (P) | .20** | .32*** | .22*** | .29*** | .21*** | .48*** | .46*** | .49*** | −.41*** | .25*** | .44*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 13 | Perceived realism of media messages (P) | −.08 | .00 | .01 | .11* | −.03 | −.13* | −.03 | −.07 | .11* | −.08 | −.05 | .01 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 14 | Media skepticism (P) | .03 | .05 | .01 | −.01 | .08 | .02 | .09 | .09 | −.06 | .04 | .17* | .05 | −.12* | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 15 | Media message completeness (P) | .04 | .01 | .08 | .04 | −.03 | .02 | .03 | −.01 | −.04 | .04 | .03 | .04 | .18** | −.13* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 16 | Sexual media diet (Y) | −.15* | −.07 | .02 | .06 | −.04 | .01 | .07 | .09 | .02 | .00 | .09 | .15* | −.02 | .02 | −.04 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 17 | Evaluative media mediation (Y) | .30*** | .20** | .45*** | .28*** | .01 | .13* | .17* | .19** | −.14* | .16 | .40*** | .20** | −.05 | .13* | .05 | .13* | 1.00 | |||||

| 18 | Evaluative media mediation (P) | .27*** | .36*** | .30*** | .38*** | .12* | .32*** | .38*** | .38*** | −.30*** | .29*** | .19** | .40*** | .02 | .09 | .05 | .03 | .33*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 19 | Restrictive media mediation (Y) | .07 | .09 | .31*** | .14* | −.05 | −.04 | .00 | .05 | −.05 | .04 | .22*** | .04 | −.03 | .12* | .04 | .01 | .56*** | .17* | 1.00 | |||

| 20 | Restrictive media mediation (P) | .01 | .07 | .13* | .17* | .10 | .09 | .11* | .15* | −.14* | .05 | .07 | .09 | .00 | .09 | −.03 | −.10 | .11* | .35*** | .31*** | 1.00 | ||

| 21 | Frequency of media and sex discussion (Y) | .27*** | .23*** | .42*** | .22*** | .07 | .12* | .21** | .26*** | −.21** | .13* | .55*** | .31*** | .00 | .15* | −.02 | .18** | .56*** | .26*** | .43*** | .12* | 1.00 | |

| 22 | Frequency of media and sex discussion (P) | .21** | .34*** | .28*** | .34*** | .20** | .41*** | .46*** | .48*** | −.39*** | .27*** | .36*** | .60*** | .04 | .00 | .04 | .12* | .27*** | .49*** | .16* | .22*** | .40*** | 1.00 |

p<.05.;

p<.001.;

p<.0001.

Table 4.

Correlation table for outcome variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Perceived parent permissiveness | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | Attitudes toward teen | .50*** | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | Normative beliefs about teen sex | −.02 | .18* | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Self-efficacy to abstain from sex | −.34*** | −.39*** | −.04 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 5 | Willingness to hook-up though unwanted | .41*** | .46*** | .01 | −.41*** | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 6 | Intentions to have sexual activity | .31*** | .45*** | .20* | −.31*** | .38*** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 7 | Attitudes toward sexual communication | −.22*** | −.33*** | .02 | .45*** | −.26*** | −.25*** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 8 | Intentions to comm with med professional | −.05 | −.18** | −.02 | .19** | −.10 | −.16* | .29*** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 9 | Attitudes toward teen contraceptive use | −.30*** | −.24*** | .14* | .40*** | −.33*** | −.16* | .49*** | .10 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 10 | Self-efficacy to use contrace ption | .05 | .01 | .11 | .30*** | −.07 | .07 | .27*** | .17* | .30*** | 1.00 | |||||

| 11 | Willingness to have unprotected sex | .32*** | .39*** | .09 | −.50*** | .54*** | .41*** | −.35*** | −.18* | −.35*** | −.14* | 1.00 | ||||

| 12 | Teen risky online behaviors | .08 | .26*** | .24** | −.30*** | .21*** | .24*** | −.09 | −.12* | −.03 | −.01 | .23* | 1.00 | |||

| 13 | Perceived realism of media messages | .00 | .15* | −.03 | −.13* | .15* | .13* | −.07 | −.03 | −.08 | −.05 | .05 | .04 | 1.00 | ||

| 14 | Media skepticism | −.07 | −.05 | .14* | .07 | −.04 | −.04 | .18* | .00 | .26*** | .23*** | .00 | .15* | −.05 | 1.00 | |

| 15 | Media message completeness | −.05 | .04 | .00 | −.11* | .08 | .10 | −.07 | .07 | −.09 | −.08 | .11 | −.03 | .07 | −.14* | 1.00 |

p<.05.;

p<.001.;

p<.0001.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for parent (P) and youth (Y) pretest variables

| Intervention | Control | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | min | max |

| Parent-adolescent connectedness | ||||||||

| Quality of parent-adolescent communication (P) | 3.13 | 0.38 | 3.12 | 0.42 | 3.12 | 0.40 | 1.75 | 4.00 |

| Quality of parent-adolescent communication (Y) | 3.19 | 0.52 | 3.22 | 0.47 | 3.20 | 0.50 | 1.14 | 4.00 |

| Supportive parenting (P) | 3.60 | 0.44 | 3.60 | 0.41 | 3.60 | 0.42 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Supportive parenting (Y) | 3.47 | 0.59 | 3.49 | 0.56 | 3.48 | 0.57 | 1.33 | 4.00 |

| Parent sexual health communication cognitions | ||||||||

| Importance | 3.66 | 0.43 | 3.63 | 0.42 | 3.64 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Comfort | 3.42 | 0.59 | 3.39 | 0.62 | 3.40 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Self-efficacy | 6.03 | 1.00 | 6.09 | 0.92 | 6.06 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 7.00 |

| Outcome expectancies | 3.06 | 0.38 | 3.10 | 0.39 | 3.08 | 0.38 | 2.05 | 4.00 |

| Reservations | 1.62 | 0.46 | 1.64 | 0.47 | 1.63 | 0.47 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Perceived role | 3.38 | 0.66 | 3.39 | 0.65 | 3.38 | 0.65 | 2.00 | 4.00 |

| Parent sexual health communication behaviors | ||||||||

| Frequency of sexual health discussions (P) | 2.75 | 0.83 | 2.80 | 0.71 | 2.78 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Frequency of sexual health discussions (Y) | 2.54 | 0.83 | 2.42 | 0.85 | 2.48 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Parent media-related cognitions | ||||||||

| Perceived realism | 2.12 | 0.58 | 2.11 | 0.57 | 2.11 | 0.57 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Media skepticism | 3.29 | 0.56 | 3.30 | 0.48 | 3.29 | 0.52 | 1.60 | 4.00 |

| Media message completeness | 2.23 | 1.38 | 2.34 | 1.34 | 2.29 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Parent media-related behaviors | ||||||||

| Evaluative media mediation (P) | 3.18 | 0.64 | 3.24 | 0.57 | 3.21 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Evaluative media mediation (Y) | 2.63 | 0.87 | 2.61 | 0.82 | 2.62 | 0.85 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Restrictive media mediation (P) | 3.18 | 0.69 | 3.21 | 0.66 | 3.20 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Restrictive media mediation (Y) | 2.56 | 0.92 | 2.47 | 0.91 | 2.51 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Frequency of media/sex discussions (P) | 2.87 | 0.82 | 2.97 | 0.78 | 2.78 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Frequency of media/sex discussions (Y) | 2.37 | 0.98 | 2.35 | 1.00 | 2.48 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Youth media-related outcomes | ||||||||

| Sexual media diet | 13.14 | 12.38 | 15.63 | 13.61 | 14.43 | 13.07 | 0.00 | 84.00 |

| Teen risky online behaviors | 1.44 | 0.43 | 1.55 | 0.56 | 1.50 | 0.51 | 1.00 | 3.63 |

| Perceived realism | 2.20 | 0.65 | 2.33 | 0.61 | 2.26 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Media skepticism | 2.88 | 0.53 | 2.96 | 0.56 | 2.92 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Media message completeness | 2.41 | 1.31 | 2.38 | 1.30 | 2.39 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Youth predictors of sexual behavior | ||||||||

| Perceived parental permissiveness | 1.64 | 0.55 | 1.53 | 0.55 | 1.58 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 3.40 |

| Attitudes toward teen sex | 2.09 | 0.59 | 2.05 | 0.63 | 2.07 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Normative beliefs about teen sex | 52.12 | 23.81 | 50.38 | 23.11 | 51.16 | 23.39 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Self-efficacy to abstain from sex | 3.43 | 0.53 | 3.38 | 0.53 | 3.40 | 0.53 | 1.20 | 4.00 |

| Willingness to hook-up though unwanted | 1.86 | 0.78 | 1.89 | 0.72 | 1.87 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Intentions to have sexual activity | 1.47 | 0.68 | 1.46 | 0.67 | 1.46 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Youth predictors of safe sexual behaviors | ||||||||

| Attitudes toward sexual communication | 3.39 | 0.54 | 3.32 | 0.54 | 3.36 | 0.54 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Intentions to communicate with a med professional | 2.15 | 0.98 | 2.03 | 0.87 | 2.09 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Attitudes toward teen contraception use | 3.39 | 0.62 | 3.40 | 0.48 | 3.39 | 0.55 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Self-efficacy to use contraception | 2.90 | 0.74 | 2.78 | 0.75 | 2.84 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Willingness to have unprotected sex | 1.45 | 0.70 | 1.35 | 0.55 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

Antecedent Analyses

Results from the antecedent analyses can be found in Table 6. Participants in the intervention group had greater increases from pretest in quality of parent-adolescent communication than participants in the control group, and this difference held for both parent-and youth-rated communication quality. Parents in the intervention group had greater increases in media skepticism from pretest and greater decreases in ratings of media message completeness from pretest than parents in the control group. Interestingly, although parents did not report different levels of family media rules, youth in the intervention condition were more likely to report increases in having family media rules from pretest than youth in the control condition, OR=2.36.

Table 6.

Results from intent-to-treat analyses for antecedent measures

| Measure | b | SE | p-value | d (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent-adolescent connectedness | ||||

| Quality of parent-adolescent communication (P) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.15 (−.08-0.38) |

| Quality of parent-adolescent communication (C) | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.16 (−.07-0.40) |

| Supportive parenting (P) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.69 | |

| Supportive parenting (C) | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.09 | |

| Parent sexual health communication cognitions | ||||

| Importance | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.48 | |

| Comfort | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.41 | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.32 | |

| Outcome expectancies | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.80 | |

| Reservations | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.87 | |

| Perceived role | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| Parent sexual health communication behaviors | ||||

| Frequency of sexual health discussions (P) | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.27 | |

| Frequency of sexual health discussions (C) | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.83 | |

| Parent media-related cognitions | ||||

| Perceived realism | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |

| Media skepticism | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.23 (−0.01-0.47) |

| Media message completeness | −0.57 | 0.13 | <.0001 | −.47 [(−0.24)-(−0.70)] |

| Parent media-related behaviors | ||||

| Adolescent’s sexual media diet | −0.00 | 0.05 | 0.97 | |

| Evaluative media mediation (P) | −0.06 | 0.06 | 0.29 | |

| Evaluative media mediation (C) | −0.07 | 0.08 | 0.36 | |

| Restrictive media mediation (P) | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.09 | |

| Restrictive media mediation (C) | −0.04 | 0.08 | 0.62 | |

| Frequency of media/sex discussions (P) | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.20 | |

| Frequency of media/sex discussions (C) | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.69 | |

| Media rules (P) | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.40 | |

| Media rules (C) | 0.86 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 2.36 (OR)* |

Odds ratio reported for binary outcomes

Youth Outcome Analyses

Results from the youth outcome analyses can be found in Table 7. Youth in the intervention condition reported greater decreases from pretest in perceived parental permissiveness towards sexual behavior and willingness to hook up when unwanted than youth in the control condition. Additionally, youth in the intervention condition had greater increases from pretest in positive attitudes toward sexual communication, higher intentions to communicate with a medical professional about sexual health, and higher self-efficacy to use contraception than youth in the control condition. Finally, youth in the intervention condition reported greater decreases from pretest in perceived realism of media than youth in the control condition.

Table 7.

Results from intent-to-treat analyses for youth outcome measures

| Measure | b | SE | p-value | d (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors of sexual behavior | ||||

| Perceived parental permissiveness | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.23 (−0.48-0.02) |

| Attitudes toward teen sex | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.61 | |

| Normative beliefs about teen sex | −1.15 | 2.84 | 0.69 | |

| Self-efficacy to abstain from sex | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.72 | |

| Willingness to hook-up though unwanted | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.20 (−0.44-0.04) |

| Intentions to have sexual activity | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.70 | |

| Predictors of safe sexual behaviors | ||||

| Attitudes toward sexual communication | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.23 (−0.01-0.47) |

| Intentions to communicate with a med professional | 0.29 | 0.11 | 0.008 | 0.30 (0.06-0.55) |

| Attitudes toward teen contraception use | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.14 | |

| Self-efficacy to use contraception | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.20 (−0.04-0.45) |

| Willingness to have unprotected sex | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.29 | |

| Media-related outcomes | ||||

| Teen risky online behaviors | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | |

| Perceived realism | −0.24 | 0.06 | 0.0003 | −.39 [(−0.15)-(−0.63)] |

| Media skepticism | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.42 | |

| Media message completeness | −0.19 | 0.15 | 0.20 |

Satisfaction

Overall, parents reported high levels of satisfaction with their assigned resource. Both groups reported that they learned something they did not know before [M=3.30, SD=.71; M=3.23, SD=.70; t(327)=−.86, p=0.39]. Likewise, groups reported that they were comfortable learning about adolescent sexual health in the online format [M=3.47, SD=.55; M=3.46, SD=.54; t(326)=−.24, p=0.81]. However, parents who received Media Aware Parent reported feeling more strongly that the resource could help them talk to their child about sex and relationships (M=3.52, SD=.50) as compared with the control group [M=3.40, SD=.59; t(326)=−2.03, p=0.04; d=1.54 (CI=−0.15-3.24)]. Furthermore, parents who received Media Aware Parent were more likely to say they would tell other parents about the resource (M=3.45, SD=.60) as compared with the control group [M=3.25, SD=.68; t(327)=−2.69, p=.008; d=2.08 (CI=0.20-3.96)].

Intervention parents were asked follow-up feedback questions about Media Aware Parent compared with other available resources of which they were aware. These parents overwhelmingly agreed that Media Aware Parent is more helpful (~95%), more comprehensive (~97%), and easier to use (~93%) than other available resources for parents. Approximately 98% agreed that they would recommend Media Aware Parent to other parents over other available resources.

Discussion

While research has established that high-quality parent-adolescent communication and teaching youth to think critically about media messages are protective factors for adolescent sexual health, there remains a dearth of evidence-based programs available to parents to help them develop and enhance these skills. This study presents the short-term findings from a randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of Media Aware Parent, a parent-focused online program designed to enhance parent-adolescent communication and media mediation with the goal of improving adolescent sexual health outcomes. The present short-term study revealed several positive findings as a result of parents using Media Aware Parent. The program enhanced both parent and youth reports of parent-adolescent communication quality, resulted in both parents and youth reporting more critical thinking regarding media messages, and increased youth report of their family having rules about media use. Most notably, youth outcomes related to sexual activity and safe sex behaviors were positively impacted. This is particularly significant considering that the intervention was targeted at parents, yet indirectly impacted youth in such a short period of time.

Most parents want their young adolescent children to delay sexual debut, which is linked to several negative health outcomes for youth, though parents may not be effectively communicating this. Youth whose parents used Media Aware Parent were less likely to think that their parent approved of them being sexually active as a young adolescent, presumably because parents in the intervention group communicated this effectively. This is a significant finding as perceived parental permissiveness of sex has been consistently linked to early sexual behavior. A large study found that adolescents’ perception of their mother’s disapproval of them being sexually active was associated with a lowered probability of the youth having sex or becoming pregnant in the following 12 months (Dittus & Jaccard, 2000). Additionally, parents who used Media Aware Parent were able to help their child be less willing to go along with unwanted hook-ups. Young adolescents may lack sexual agency. Less than half (41%) of young women and only 63% of young men report that their first intercourse was something that they really wanted to happen at that time (Martinez et al., 2011). Since early sexual experiences can impact later sexual behaviors and relationships, it is important to promote sexual agency and active consent in conjunction with messages that promote abstinence or delaying sexual activity.

Adolescents should be encouraged to develop positive attitudes and skills related to sexual health communication and using protection/contraception during sexual activity, even if they are not currently sexually active. Parents who received Media Aware Parent helped their child feel more positive about communicating about sexual health and increased their child’s likelihood for speaking to a medical professional about sexual health. They also helped their child be better prepared to use contraception, if needed. The keys to consistent contraceptive use are communication about contraception with sexual partners (Johnson, Sieving, Pettingell, & McRee, 2015) and skilled, confidential visits with a medical provider (Ott, Sucato, & Committee on Adolescence, 2014). Unfortunately, only about a third of teens report that they spent time alone with a doctor or health care provider in the past year (Copen, Dittus, & Leichliter, 2016). Further, only around half of adolescents discuss contraception or sexually transmitted infections with their partner at first sex (Ryan, Franzetta, Manlove, & Holcombe, 2007). Promoting communication about safe sex behaviors is essential to reducing unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections in adolescence.

There were several youth sexual health outcomes that did not seem to be influenced by the intervention in the short term. Some of the outcomes measured might not have had sufficient variability to show positive change. Younger adolescents often do not intend to have sex in the near future and feel efficacious in remaining abstinent. As adolescents get older and begin to consider having sex, continued high-quality parent-adolescent communication could be a protective factor in encouraging adolescents to delay sexual debut. Youth participants at pretest already held very positive attitudes about contraception/protection and low willingness to have unprotected sexual activity. It is possible that continued high-quality parent-adolescent communication about safe sex as adolescents get older and become sexually active could encourage youth to maintain these healthy attitudes. Youth attitudes or normative beliefs about teen sexual activity did not change as a result of the intervention. Media Aware Parent is a parent-focused program designed to improve parent-adolescent communication about sexual health and media messages. While the program includes information for parents on the impact of peers on adolescent decision-making, the program focuses on helping parents communicate medically-accurate information as well as their personal values about sex and relationships; the program does not focus on societal or peer-related beliefs about teen sex. A program more directly focused on correcting inaccurate beliefs about teen sexual activity may be needed to impact these youth outcomes.

The parent-adolescent relationship is an important protective factor for adolescent sexual health. This study revealed that a parenting program designed to improve parent-adolescent communication about sex and relationships enhanced the general quality of parent-adolescent communication, as evidenced from both parent and child perspectives. This is an important finding given that communication quality impacts the effectiveness of conversations about sexual health. While the program impacted communication quality, no changes were found for measures of supportive parenting. Overall, families reported high levels of parental support at the start, which were higher than communication quality, indicating that supportive parents may still struggle with quality communication. Interestingly, no changes were found in parents’ feelings toward sexual health communication or efficacy to communicate with their child about sex, nor did they appear to engage in more frequent communication about sex and/or media messages with their child as a result of completing Media Aware Parent. At pretest, parents reported high levels of comfort, self-efficacy, and positive outcomes expectancies related to sexual health communication with their adolescent. These findings suggest that impact of Media Aware Parent on important youth sexual health outcomes resulted from the program’s positive impact on parent-adolescent communication quality, not changes in parental beliefs about sexual communication or increases in communication frequency. Since the present study evaluated Media Aware Parent against an active control, it is possible that parents in both groups frequently discussed sexual health with their children, but the tone and content of those conversations could have varied greatly. Research has shown that parent-child sexual health communication is most effective when it takes place within the context of high-quality parent-child communication that is open, honest, and respectful (Flores & Barroso, 2017). Similarly, the reservations about sexual communication measures focuses primarily on communicating about sex and birth control, and does not include reservations about speaking about other sexual health topics such sexual agency or how to talk to a medical professional about sex. While reservations about sexual communication were low at pretest, it is possible that parents in the both the active control and intervention group experienced lowered reservations about talking with their teen about topics such as sex and birth control. A more specific measure of parent reservations about sexual health topics such as sexual agency and talking to a medical professional would provide a more complete picture of the program effects on parent reservations about sexual health communication. Program improvements could include future research to better understand optimal program dosage and explore ways to enhance the program to encourage parents to complete more of the program and share more content with their adolescent child.

Critical thinking about media messages can prevent the internalization of misinformation or unhealthy sexual scripts. Importance should be placed on both parents and youth to analyze the information found in media messages for accuracy, realism, and potential biases. This study revealed that both parents’ and youths’ media literacy skills benefitted from their parents using Media Aware Parent, whereby parents were more skeptical of media messages and less likely to accept that an unhealthy media message (e.g., an advertisement using sexto promote alcohol) was a complete source of information. When parents are media literate, they can in turn, help their children think more critically about media messages. Interestingly, parents’ perceived realism of media messages was not impacted by the program; it is possible that most adults already perceive media messages, especially those depicting teen behaviors, to be unrealistic. Youth whose parents used Media Aware Parent, were less likely to agree that media messages are realistic. Other media-related cognitions did not change among youth in the short-term. However, enhancements in these outcomes may be seen over time as parents and youth continue to practice analyzing and evaluating media messages.

Talking about media messages as a family and having some restrictions on media exposure have been found to be effective mediation strategies and may attenuate negative effects of media on youth sexual health. This study did not reveal a change in the frequency of communication about media messages as a result of the intervention. However, frequency of communication may not be as important for promoting health as the media literacy cognitions and skills that are brought to critically analyzing media messages. Interestingly, parents in both conditions reported similar levels of using family media rules, but youth whose parents used Media Aware Parent were more likely to recognize these family media rules were in place. This suggests that Media Aware Parent resulted in parents being more skilled at either communicating or implementing the family rules. No change in the youths’ sexual media diet was detected as a result of the intervention. It is plausible that parents may have drawn attention to the sexual content in media, which could result in youth rating their sexual media exposure higher. Additionally, as children grow and become increasingly independent, parents may be limited in their level of control over their child’s media exposure; parents may be more effective by equipping their children to be critical media consumers. Surprisingly, no changes were seen for parent or youth reports of the frequency of parental evaluative or restrictive media mediation. This may also be a function of the intervention improving quality over quantity of behavior. Overall, this research provides evidence that a program for parents that includes instruction on media mediation strategies is not only effective in enhancing parents’ media literacy skills, but can also have a positive impact on their children’s media literacy skills and can help families effectively create and communicate media rules.

This study had several strengths. Intent-to-treat analyses avoid effects of non-compliance that may disturb the effect of the initial random assignment and provide a more realistic evaluation whereby parents sometimes do not start or complete intervention programs. Furthermore, the inclusion of an active control where parents received professional resources on topics related to adolescent sexual health allowed the efficacy testing of the program to go beyond the effects of simply providing knowledge to parents. While both groups were armed with medically-accurate facts about sexual health, the youth whose parents’ resource focused on communication and media demonstrated many unique positive outcomes. Finally, analyzing data from both parents and children allowed the examination of program effects as self-reported by parents but also validated by their child’s report.

The limitations of this study should also be considered. Longer-term research is needed to discover if the effects of Media Aware Parent persist over time or whether some effects degrade or emerge. The majority of younger adolescents are not sexually active, reducing the possibility of seeing change in some sexual health outcomes in such a short timeframe (i.e., four weeks). The average age of youth participants in this study was thirteen years old, and only 3% of adolescents report having had sex before the age of 13 (Kann et al., 2018). Sexual behaviors reported by this sample of youth were equally low (less than 2% reported experience with vaginal or oral sex and less than 1% reported experience with anal sex). However, it is important to note that this study included participants in grades seven through nine, and 20% of 9th graders report having had sex (Kann et al., 2018). Therefore, during these critical years sexual debut takes place for a significant number of youth. Finally, while intent-to-treat analyses are a strength, the effect of the intervention is likely underestimated as the analyses includes participants who did not engage or fully engage in the intervention.

Conclusion